though pirates are romanticized today as swashbucklers, they were primarily thieves and murderers

Source: Pixabay

though pirates are romanticized today as swashbucklers, they were primarily thieves and murderers

Source: Pixabay

Pirates are often romanticized as resourceful entrepreneurs on the fringes of the wilderness, taking daring risks while creating egalitarian communities on ships that honored a code of behavior. More accurately, pirates were thieves who stole from ships, seized entire ships, and raided plantations on land. Pirates were (and are) highway robbers operating on water.

Pirate ships are the modern equivalent of get-away cars of bank robbers. Starting in the 1500's the English government authorized ships to be "official" pirates called privateers, to attack Spanish, French, and Dutch ships and colonies. Interrupting the merchant trade of a rival weakened its ability to generate revenue and pay for troops and supplies, created internal pressure from a country's business elites to conclude a war, and generated profits for the friends of a monarch.

English kings and queens endorsed piracy when it impacted the Spanish, French, and Dutch. When England became the dominant seafaring nation starting in the early 1700's, English officials clamped down on piracy because English trade and profits were being impacted.

Other nations authorized their own privateers to attack the English in a form of undeclared-but-official economic warfare. In the 1600's and 1700's, ship captains were authorized by different European monarchs through a document called a letter of marque to use private ships to seize merchant vessels of enemy nations. As Spanish colonies in Central and South America sought independence in the 1800's, groups claiming to be governments issued letters of marque which justified capturing Spanish merchant vessels in the Gulf of Mexico. The documents provided a thin veneer of legitimacy to pirates based in Louisiana, including Jean and Pierre Lafitte as late as the 1800's.

Captured ships were known as "prizes." Privateers licensed by the English government could put some of their crew on a captured ship and sail it back to a port in North America. A judge would oversee an auction of the ship and its cargo, then distribute the revenue to captains and crew. Through such sales, privateers obtained legal wealth. Pirates who seized ships looaded with tobacco, rum, lumber, and various other items of mechandise also needed to convert cargo into cash. They conducted similar sales, but in private dealings without legal authorization. Some colonial governors in English colonies, such as Governor Eden in North Carolina, were bribed to overlook such sales.

In the 1500's, Spain was a dominant military power in Europe. It had full control over all colonies in the Western Hemisphere except for Brazil. Those colonies, and the ships going to and from them, were the primary targets for privateer and pirate crews of many nations.

The Spanish treasure fleet carried silver and gold from the New World to Seville. Ships loaded with such wealth sailed from Havanna, passed through the Florida Channel between Florida and the Bahamas, then turned east off the North Carolina coast to continue following the trade winds across the Atlantic Ocean.

That pattern helped determine where pirates chose to base their ships. From the beginning, English colonies were considered as launching points for seizing Spanish ships. Plans to make Jamestown a haven for English pirates were complicated by direction from the Virginia Company for the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery to look for a place to settle that was a hundred miles upstream from the Chesapeake Bay. The final location on Jamestown Island minimized the risk of attack by the Spanish, but reduced the ability to send ships on patrol to find Spanish targets.

the Spanish treasure fleet sailed east before reaching the latitude of Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the West-Indies or the islands of America in the North Sea; with ye adjacent countries... (by Herman Moll, 1732)

In 1586, Francis Drake seized Spanish-controlled Cartegena in South America and looted the town. Drake's ships may have been loaded with 200 enslaved people when he stopped at Roanoke Island that year, on the way home from Cartegena. The Roanoke Island colonists accepted his offer of a return trip to England and only a token number of people were left to overwinter before new ships would arrive in 1587. Drake may have left those 200 enslaved people on Roanoke Island or on an island nearby, since he lacked enough food to carry them across the Atlantic Ocean. When the 1587 colonists arrived, only Native Americans were waiting for them.

Capturing a Spanish ship in the Treasure Fleet bringing silver and gold to Spain was a pirate's dream, but ships headed west to the colonies were also an attractive target. English pirates brought the first enslaved Africans to Virginia in 1619, after seizing them from a Portuguese ship carrying human cargo to Mexico.

French, Dutch, and English pirates preyed on Portuguese and Spanish ships, and on ships from any nation when convenient. In addition, pirates raided towns and poorly-defended plantations on shore.

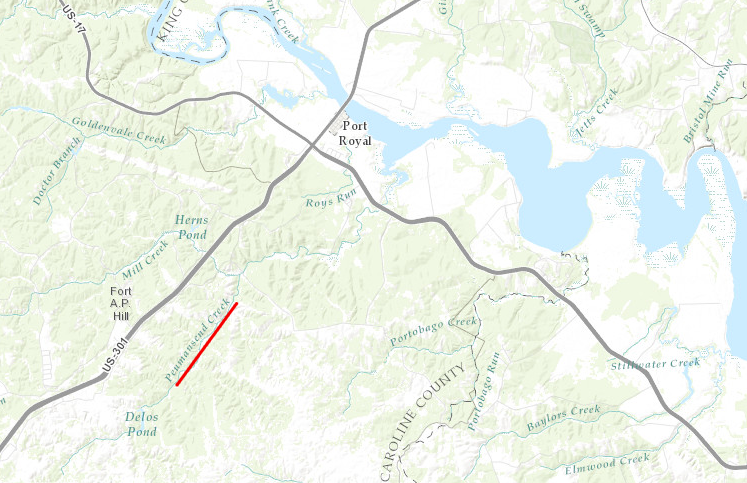

Far inland in Caroline County, Peumansend Creek is reportedly named after a French privateer or pirate. Sometime before 1670, according to local lore, Captain Peuman raided up the Rappahannock River one too many times. Local colonists blocked his escape back to the Chesapeake Bay, and he ended up trapped in a creek near the town of Port Royal. Peuman was killed there, and today the place where he "met his end" is called Peumansend Creek.1

Peumansend Creek supposedly memorializes where a privateer/pirate named Peuman was killed

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Pirates might sail a captured ship to a port where officials winked at their presence, and sell the cargo to the equivalent of modern "fences" trafficking in stolen goods. Hogsheads of tobacco or other bulk cargo on captured ships would be thrown overboard, if the ship itself was desired. Other ships with hard-to-sell cargoes were simply sunk or burned after the easy-to-sell items were transferred to the pirate's ship.

Colonial governors were willing to make arrangements with pirates; they brought valued goods that isolated colonies rarely saw from legitimate trade. Government officials also were susceptible to bribes for personal reward, in exchange for allowing pirates to acquire supplies and use ports as a base of operations. In 1655, the English seized Jamaica from the Spanish. Until an earthquake dropped Port Royal in Jamaica below sea level in 1692, it was a haven for pirates.

A hurricane wrecked the Spanish Treasure Fleet as it sailed along the Florida coast in 1715. Spain sent various ships to recover the gold and silver from the wrecked vessels. English officials in Jamaica outfitted a fleet of ships to intercept "pirates" that would try to plunder that treasure, but in reality the expedition was designed to collect as much as possible before the Spanish. The English leader of that expedition, Henry Jennings, ended up attacking the Spanish garrison on the Florida beach where the recovered gold and silver were stockpiled and stealing the wealth.

Governor Spotswood in Virginia had the same idea as the governor of Jamaica. Spotswood outfitted a vessel to sail to Florida in 1716 and grab a share of what the storm had scattered, but a Spanish warship captured the ship. The men on the ship from Virginia were carried to Mexico, and claims that they were trying to protect the Spanish loot froom pirates were dismissed. The vessel was treated as a prize and sold, and the men from Virginia were briefly imprisoned.

Sailors could engage in a shifting cycle of illegitimate piracy, intermixed with legitimate privateering (legal piracy) and private operations:2

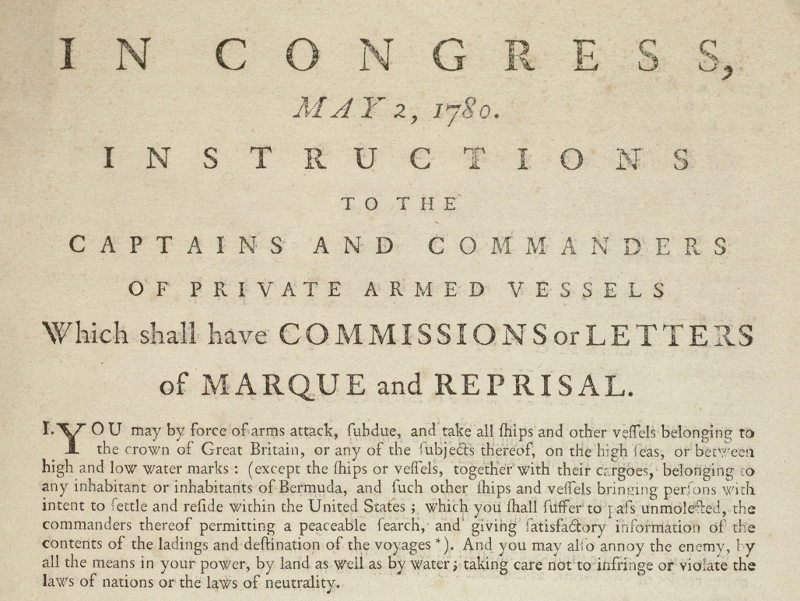

Kings and queens "outsourced" to expand their navies by authorizing privateers, avoiding the political headaches of raising taxes to build more warships and find crews to staff the vessels. During the American Revolution, the Continental Congress did the same. The official letter of marque endorsement meant that privateers were enemy combatants, and should be protected as prisoners of war if captured rather than executed summarily as pirates.

Ship captains and crews with letters of marque could go rogue and seize merchant vessels without any official blessing. In colonial times, ships sailing to and from Virginia suffered from unauthorized piracy as well as privateering authorized by hostile nations. When nations were at peace and letters of marque were scarce, captains and crews could switch to whatever unofficial opportunities were available.

in 1780, the Continental Congress issued letters of marque that authorized privateers to attack English shipping

Source: Library of Congress, Instructions to the captains and commanders of private armed vessels which shall have commissions or letters of marque and reprisal

The "rules of the games" were flexible. Determination of what was legal varied, depending upon who was making the decisions. Experienced captains and crews switched back and forth between privateer and pirate, or simply signed up for ordinary commercial trips, depending upon the demand for their services. Before coming to Virginia in 1607, even John Smith had served on a pirate ship in the Mediterranean.3

The transition of the colony of Virginia from royal to Parliamentary control between 1651-1652 created confusion regarding which laws applied in the colony. After Parliament passed the first Navigation Act of 1651, Dutch ships were banned from trading with the colony of Virginia. Virginia trips were banned from sailing to destinations other than England and its various possessions.

One Jamestown merchant was caught up in the change in policy, sailing The Fame of Virginia to the Netherlands when Virginia was loyal to the king but returning in 1752 after Parliament had seized control of the Virginia colony.

Upon the ship's return to Virginia, another sea captain seized The Fame of Virginia and claimed it as a prize based upon the ship's violation of Parliamentary law. The Northampton County Court rejected that claim. When the captain who seized the ship left the court after losing his case, he flouted the court's authority and promptly sailed away with his "prize."

County taxpayers feared they would be required to provide compensation, since county officials had made the mistake of releasing the captain who sailed away. After a Dutch ship was captured, colonial officials conspired together to claim that ship as property of the colony. They sold it at a great discount to the owner of The Fame of Virginia - with the arbiters who set the price getting compensated by that ship's owner. Through that arrangement, the owner recovered the value of the stolen The Fame of Virginia.

The boundary between illegal piracy and legalized privateering depended upon the circumstances. Creative interpretations of the law were made at times.4

Dutch privateers, not pirates, caused the greatest damage to Virginia shipping in the Chesapeake Bay area during wars between the Netherlands and England. In 1667, Dutch privateers disguised themselves as English ships and sailed into the Chesapeake Bay. They crippled the one English warship stationed there and captured the fleet of merchant ships preparing to sail to England with full loads of tobacco.

The privateers had time to send landing parties ashore to loot plantation houses along the James River. Before the militia under Governor William Berkeley could organize a response, the Dutch sailed away with all the tobacco ships they could handle and burned the rest of the fleet.

In 1673, another set of Dutch raiders repeated their success. They spent days collecting tobacco from Virginia and Maryland merchant vessels, overcoming efforts of ship captains to flee up the Nansemond and James rivers.5

Though pirates are renowned today as flashy, independent characters, some started essentially as contractors hired by English investors seeking quick profits from robbing the Spanish. During the days of Queen Elizabeth I when Spain and England were at war, a quick way to increase wealth was to outfit a ship, obtain a letter of marque from the government, and hire a captain and crew to intercept Spanish ships returning across the Atlantic Ocean loaded with silver and other products extracted from South America and Central America.

The economic opportunity was still extremely attractive even after James I arranged for peace between Spain and England in 1604. London merchants and wealthy members of the nobility financed successful colonies not only on the North American mainland but also in the Caribbean, starting with St. Christopher (St. Kitts) in 1624. Growing tobacco and other crops did not create a high return on investment until the planters on Barbados switched to creating slave-based sugar plantations in the 1640's, but there was always the opportunity to seize a loaded vessel from another country while providing supplies and trading in the Caribbean.

Providence and Tortuga were founded as pirate bases. According to one scholar:6

Thanks to intimidation, robbery at sea was often a pretty easy way to make a living. Pirates consciously spread fear regarding their behavior, and announcing their presence by hoisting a blood-red flag. Blackbeard hoisted a black flag with a death's head, while variants used by other pirates are replicated today as the "Jolly Roger" flag with a skull and crossbones. Captains and crews who quickly surrendered hoped to be treated better than those who fought back or tried to escape.

Crew members from captured vessels ("prizes") would be invited to join the pirates, who at times created a fleet with multiple ships that required additional crew. Because European and American shipowners paid such low wages and ship captains were often harsh in their treatment of the sailors, an invitation to "jump ship" and join the pirates was attractive. The egalitarian nature of pirate ships was also an inducement. Pirate captains lacked the power to flog or punish members of their crew without the endorsement of the majority of the other sailors.

Sailors on captured ships who refused to join the pirates could be lucky enough to be released to continue the voyage, after the valuables had been stolen from their ship.

Like modern burglars, pirates sought cash and goods easy to sell. They stole the personal possessions of captured crew and passengers, and resupplied their ships with sails, ropes, medicines, tools, food, rum, and other items needed to maintain a pirate ship and keep the crew happy.

At times, pirates would trade their worn-out vessels for a captured merchant ship in better condition in the maritime equivalent of stealing a faster car. Ships not suitable for use by the pirates could be burned, or ship carpenters were forced to drill holes below the waterline so the wooden vessels would quickly sink. Putting captives on board the pirate ship and sinking unneeded captured ships enabled pirates to keep their location secret from any government warships on patrol.

Unlucky crew and passengers who were not released could be imprisoned in dark and smelly holds below decks on a pirate-controlled ship. Captives also could be marooned on a plundered hulk from which sails and ropes had been removed. There was a chance such victims could be rescued, and also a chance that they would die first on the ship.

A quick surrender by a ship after being confronted by pirates might result in gentle treatment, but pirates were mercurial and often undisciplined. Captains, crews, and passengers could be tortured or killed for information/entertainment, and the fate of captured ships varied. In the Pirates of the Caribbean movies, the famous code of the pirates was more of a guideline than a law to be followed.

some pirates flew red flags to signal no quarter, while others flew black flags that intimidated captains/crew of merchant ships

Source: Library of Congress, Major Stede Bonnet.

Ships sailing from Europe across the Atlantic Ocean kept a watch on the horizon and tried to flee from strange vessels. When Frantz Ludwig Michel sailed from England to Yorktown in 1702 at the start of the War of the Spanish Succession, he recorded how evasion had been successful:7

Pirate crews made decisions by democratic vote. Strong-willed captains made decisions, but mutinies were not uncommon when there was not a consensus among the crew. William Dampier, a pirate who lived for a part of his life in Virginia, captained one of several pirate ships sailing in the Pacific Ocean near Chile in 1704 when another pirate captain marooned a troublesome sailor on an isolated island there.

Four years later, Dampier was navigator on the ship that rescued the castaway, Alexander Selkirk. Dampier's descriptions of his experiences helped stimulate Jonathan Swift to write Gulliver's Travels and Daniel Defoe to write Robinson Crusoe.

After the War of Spanish Succession concluded with the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, there was a surge of piracy. Privateers with letters of marque lost their offficial commissions at the same time the Royal Navy was downsized from 50,000 to 13,500 sailors. There were few legitimate jobs available for able-bodied seamen. One English pirate based at Nassau in the Bahamas, Benjamin Hornigold, claimed that he was still a privateer who would capture French and Dutch chips but bypass opportunities to capture English ships.

Horigold's crew disagreed with that approach, in part because there were plenty of attractive English ships which they could seize, and replaced him with another person as captain. Such a decision on a merchant ship would have been treated as a mutiny' mutinous sailors could be hung. On a pirate ship, the power of the crew to change a captain was routine.8

the life of pirates and privateers has been romanticized and converted into tourist events and "Talk Like a Pirate Day" - aaargh!

Source: Library of Congress, A Pirate's Life For Me

Ten years after the successful 1673 Dutch raid in the Chesapeake Bay, the English began to station a Royal Navy guardship at the Virginia colony to protect the commercial shipping from privateers with letters of marque and from pirates. In 1688, the HMS Dumbarton seized four men who were suspected of being pirates. They were in a small boat on the Chesapeake Bay, and were thought to be pirates because the boat carried three chests loaded with gold coins and items of silver.

It turned out one of the four was Edward Davis, who had sailed out of Hampton in 1683 with William Dampier on a pirate expedition (though they also obtained letters of marque from the king of England). Davis ended up as captain of the Batchelor's Delight, which raided Spanish shipping and coastal villages on the west coast of South America until King James II issued a proclamation of amnesty for pirates in 1687. Davis obtained a royal pardon for the crew in Jamaica, but the pirates calculated that it would be wise to split up and seek to disguise their past.

The captain of the HMS Dumbarton and the colonial officials at Jamestown were not willing to accept the pardon granted by the royal governor in Jamaica. They hoped to claim a share of the treasure seized from the four men, and the officials also feared retaliation from other pirates if the four men were punished.

Ultimately, one of the four died and the other three were shipped to England for trial. Rev. James Blair, the commissary representing the Anglican church in Virginia, was visiting London in hopes of finding a source of money to start a college in Williamsburg. He helped the pirates negotiate a plea bargain.

The English judge agreed in 1692 to release the defendants and restore their confiscated treasure, if they made a substantial contribution to the colony where they had first been arrested. The three former pirates donated the equivalent of $1 million today, and it was used to start the College of William and Mary.9

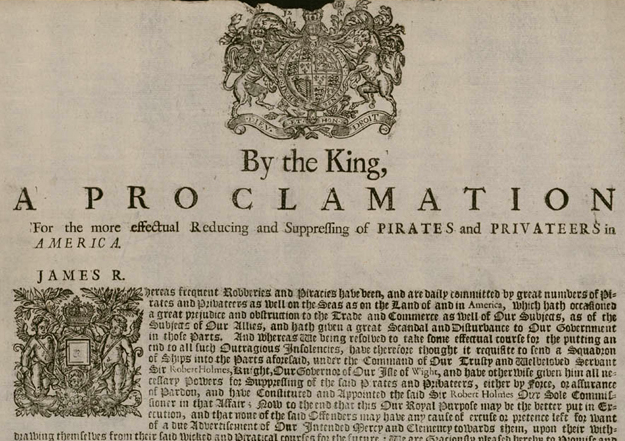

in 1688, James II granted amnesty to pirates who returned to England

Source: Library of Congress, British Attempt to Suppress Pirates

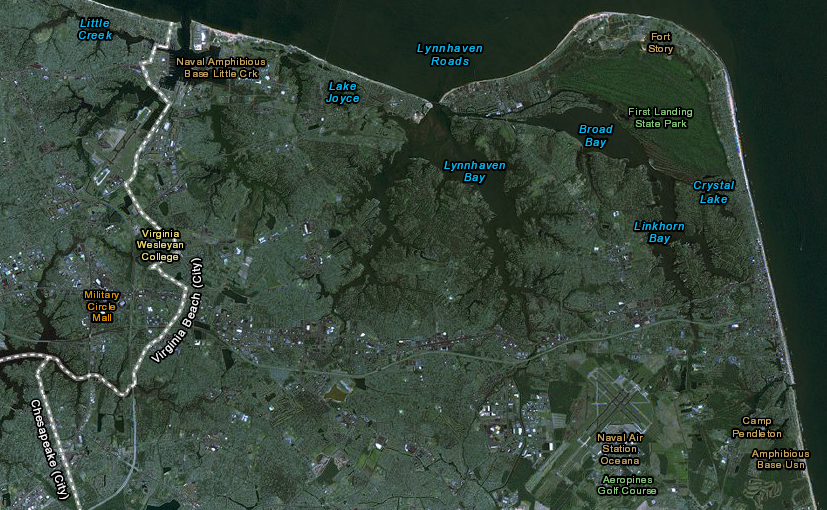

The HMS Dumbarton had been lucky enough to capture four trying-to-retire-in-peace pirates, crossing the Chesapeake Bay in an unarmed small boat. At times, the Royal Navy guardship was outgunned by the pirates. In 1699, the 16-gun Essex Prize warship was forced to evade and then finally flee from the pirate John James and his 26-gun Providence Galley. The pirates then plundered various merchant ships in Lynnhaven Bay and the Chesapeake Bay.

Despite the risk from pirates, colonists in Virginia and Maryland were not anxious to have an effective Royal Navy in the Chesapeake Bay. A ship capable of intercepting all pirates could also ensure all import and export duties were collected. As described in The Virginian-Pilot's series of articles in 2006 exploring the history of pirates in Virginia:10

Lynnhaven Bay, where pirate Lewis Guittar captured merchant ships in 1700 - but then was captured by the new guardship

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Occasionally, the small guard ship was capable of defeating even well-armed pirates. In 1700, the pirate Lewis Guittar captured a fast merchant vessel, the La Paix (Peace) in Barbados. After converting it into his pirate flagship, Guittar and La Paix seized other ships to assemble a pirate fleet. That pirate fleet captured multiple vessels off the Virginia coastline.

Lewis Guittar's success ended after he sailed into Lynnhaven Bay in April, 1700. He thought the only British warship in the Chesapeake Bay region was the dilapidated Essex Prize.

Some of the merchant vessels that were anchored in Lynnhaven Bay tried to escape, fleeing to the Atlantic Ocean and hoping they could sail faster than the pirates. One ship went the other direction, and sailed up the James River to alert the colonial authorities. The powerful warship Shoreham had arrived recently to strengthen the colony's defenses. Governor Nicholson went on board before the Shoreham quickly sailed to challenge the La Paix.

During battle in Lynnhaven Bay, the sails and rudder of the La Paix were shot away and the pirate flagship was disabled. Guittar threatened to blow it up, killing 50 or so prisoners that he had seized from other vessels rather than surrender unconditionally. To save the lives of the hostages, Gov. Nicholson agreed to grant quarter to the pirates, and assured them of a trial in England rather than in the colony.

One pirate, John Houghling, chose to jump off the La Paix and swim to shore in hopes of escaping. He was captured, and became the person tried for piracy in Virginia. Houghling was found guilty and hung, together with two other pirates who had been found asleep on one of their prizes. They had been excluded from the governor's offer of clemency, because they were not on board La Paix when Governor Nicholson agreed to sending the captured pirates to England for trial.11

The presence of the 28-gun Shoreham had surprised Lewis Guittar. Sending the powerful guard ship reflected a change in colonial policy to increase protection of merchant vessels sailing between England and the Chesapeake Bay. The poorly-equipped, poorly-staffed vessels that previously served as guard ships had been ineffective in collecting revenue, but conflicts in Europe had increased the threat of authorized privateers and unauthorized pirates in the Chesapeake Bay.

Raids on French and Spanish vessels were no longer legitimized by English letters of marque after the end of Queen Anne's War/War of Spanish Succession in 1713. Peace eliminated the opportunity for privateers to get rich quick by seizing Spanish and French ships.

Some captains and crews chose to be pirates without the legitimacy of a letter of marque. The "golden age" or piracy was between 1716-1726. About 4,000 pirates were active in that decade, but an individual pirate stayed in the business just one-two years before dying or disappearing off the radar of government officials. The motto of one pirate captain was "a merry life, and a short one."

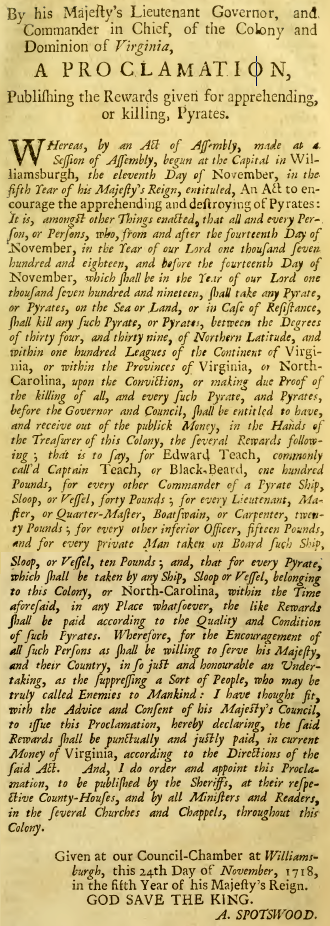

As a cost-effective way to end the piracy, King George I issued the Proclamation for Suppressing of Pirates (the Act of Grace) in 1717. It granted a pardon to pirates who surrendered by a deadline that was ultimately extended to July 1, 1719.

Some pirates, particularly those based in the Bahamas, ignored King George I's offer and continued to seize foreign merchant ships. Some accepted the pardon but then returned to piracy. In 1718, after a new royal governor expelled pirates from the Bahamas, Virginia became a prime target:12

The most famous pirate associated with Virginia today is Blackbeard, one of the last pirates to pose a serious threat to Virginia's shipping. Blackbeard (Edward Teach) was a licensed privateer during Queen Anne's War and an unlicensed pirate afterward. The details of his life are hazy, but he may have been born in Jamaica, become a crewman on a merchant ship, and then joined the Royal Navy as a youth.

After the destruction of a Spanish treasure fleet during a 1715 hurricane, many Jamaicans began looting the wrecks off the Florida coast. Teach and other English privateers liked free treasure, and they kept seizing merchant vessels from Spain and France - even though the Treaty of Utrecht had been signed in 1713 to end the War of the Spanish Succession. The Island of New Providence in the Bahamas, now the home of Nassau, was used as a base of operations.

after the War of the Spanish Succession ended in 1713, pirates still used New Providence as a base of operations to seize Spanish, French, and other ships

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Blackbeard reportedly presented a fearsome appearance that was a calculated part of his business style, not a coincidental characteristic. He may not have killed anyone, himself, until his last battle. His goal was to frighten victims into surrendering without a fight:13

Blackbeard the Pirate

Source: A general history of the pyrates (1724)

In 1718, Blackbeard organized a blockade of the main South Carolina port, Charles Town (Charleston). He managed to get a pardon from North Carolina Governor Charles Eden. The governor of Virginia, Alexander Spotswood, was less forgiving.

Technically, Spotswood had no jurisdiction over piracy committed in the Atlantic Ocean south of the Virginia border, but pirates based on the Outer Banks of North Carolina threatened ships sailing in and out of the Chesapeake Bay. North Carolina ship captains requested help from Virginia, recognizing that Governor Charles Eden was allied with Teach and unwilling to stop his piracy.

King George I had issued pardons to pirates in 1717 and again in 1718, hoping they would voluntarily switch back to legal shipping activities. Spotswood was looking for an opportunity to improve his relationship with the powerful gentry in Virginia, who were resisting his authority as governor. A strong stand against piracy would enhance colonial commerce in Virginia, increasing profits of plantation owners and thus increasing Spotswood's political power in Williamsburg.

Governor Spotswood did not wait for Blackbeard to hear about the second pardon opportunity. He dispatched Lieutenant Robert Maynard from the Chesapeake Bay to Ocracoke Island, after learning that Blackbeard's ship Adventure had become stuck on a shoal there.

Maynard took two ships, Jane and Ranger. He found Blackbeard's ship on November 22, 1718 and demanded that he surrender, but the pirates chose to attack him.

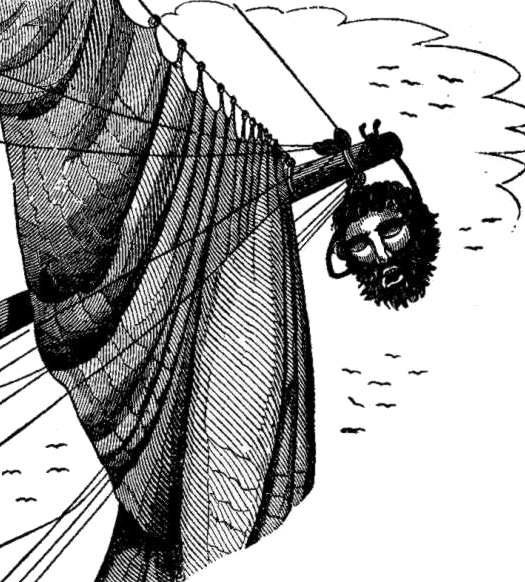

Maynard tricked Blackbeard by having his crew on the Jane go below decks. The 10 pirates boarded Maynard's ship, thinking most of the crew had been killed. Maynard and his 11 crew members came back on deck, and in hand-to-hand combat with swords and pistols they killed or captured all the pirates. Blackbeard's head was cut off and hung from the bowsprit on Maynard's ship. That displayed the success of the mission on its return to Virginia, and the severed head was then hung on a pole in Hampton.14

Blackbeard's severed head was carried back to Virginia

Source: The Pirates Own Book (p.217)

Today, marine archeologists have excavated the Queen Anne's Revenge, which sank on the Outer Banks near Beaufort Inlet six months before Lieutenant Robert Maynard defeated Blackbeard and his pirate crew on the Adventure. It was loaded with weapons. At least 30 cannon have been found so far, along with cutlasses and firearms. Archeologists even found grenades designed to be tossed by hand onto the deck or in the hold of a ship, plus the equivalent of a Molotov cocktail designed to set fire to a ships sails and rigging.15

The pirate history has been romanticized. The City of Hampton holds an annual festival commemorating his exploits and his ship the Queen Anne's Revenge, converting a once-feared military threat into an excuse for a party. The festival started in 2000 as a Hampton event, to pull some tourists across the water during OpSail 2000 in Norfolk. The continued public response (with 50,000 visitors annually) surprised tourism officials, but they have scheduled events each year.

Hampton's connection to Blackbeard provides something unique to draw tourists to the city. As the Convention & Visitors Bureau Executive Director has noted:16

graphic from poster for 2013 Blackbeard Festival in Hampton

Source: City of Hampton, About the Festival

Hampton University adopted a pirate as the school's logo in 1979. The sketch of the pirate has been revised over time, but the athletic department sales items are still covered with pirate paraphernalia.17

Hampton University has associated itself with the pirate history of the city

Source: Hampton University, Small Decal Hampton Pirates, 6 inches tall

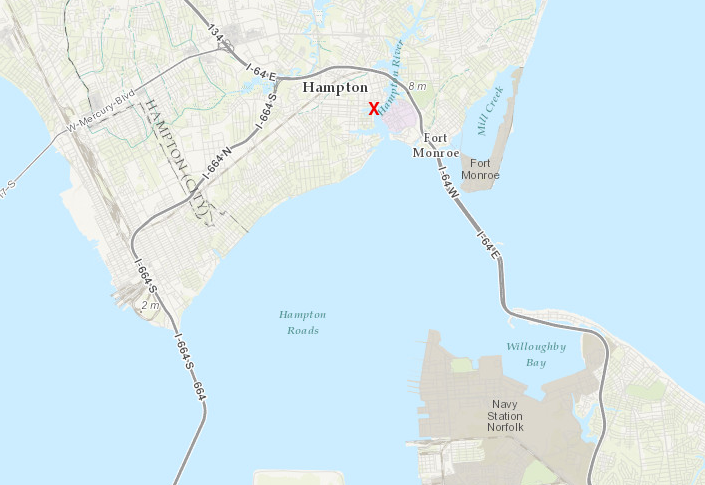

Placing the bodies of executed pirates in public locations was thought to deter others from choosing to become pirates. Spotswood had bodies hung in chains at the harbors of Tyndall's Point (York River) and Urbanna (Rappahannock River). The return of Maynard's trophy to Hampton, a gruesome event in 1718, is now a high point of the city's annual Blackbeard Festival:18

Blackbeard's Point, where Lieutenant Robert Maynard hung the pirate's head, is at the southern end of Eaton Street in Hampton

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Blackbeard was not the very last pirate in Virginia. In 1720, pirates captured a Virginia vessel near Barbados, and eight of the pirates sought to return to "civilian life" by sailing home with that vessel to the Chesapeake. The pirates were captured and six were executed, but that triggered a threat from other pirates to get revenge on Virginia.

Governor Spotswood established lookout posts at Cape Charles and Cape Henry, plus fortifications at the mouths of the James, York, and Rappahannock rivers. Those defenses were not tested, but fear of being captured and tortured by pirates while sailing back to England kept Spotswood in Virginia even after he was replaced as governor.

It was a realistic concern. Pirates led by Bartholomew Roberts captured the French governor of Martinique, who had hanged pirates earlier. In return, they hung the governor from the yardarm of his own ship.19

Pirate treasure may be buried today somewhere on Virginia's coastline. Captain Kidd sailed from the Caribbean to Boston in 1699, supposedly burying gold, silver, and jewels on the shoreline during the journey. Perhaps his loot was recovered by other pirates soon after he was captured (and later executed in England), or perhaps whatever treasure he buried may be exposed one day after a storm shifts the sands.

The role of colonial officials in dealing with pirates ended in 1776; the new state of Virginia gained that responsibility. The state's navy and state-authorized privateers protected the Chesapeake Bay and nearby waters of the Atlantic Ocean from pirates and privateers from other nations, together with the tiny United States Navy created in 1775. Virginia also created an Admiralty Court to process cases involving crime on the high seas.

The new Federal government was granted exclusive jurisdiction over piracy in the US Constitution. Since Federal courts were established in 1798, the US Navy and Federal judges have had full responsibility for suppressing and punishing piracy. One significant reason for adoption of the new US Constitution was the need for consistent policies among the 13 states for managing interstate commerce and international trade. Language adopted in 1787 was clear:20

A July 1819 piracy trial in Richmond, United States v. Smith, is still relevant in defining the US approach to international law. The crew of the Creola mutinied, seized a faster ship named the Irresistible and started capturing ships. Though cargo was stolen and passengers/crews robbed, no one was murdered.

The Irresistible sailed to Baltimore, home of some crew members. Officials there arrested them. Two were tried and executed in Baltimore. Another 17 were tried in Richmond. One was acquitted and 16 were convicted of piracy, but the judges disagreed on whether the crews actions met the definition of "piracy" under the US Congress' 1819 Act to Protect the Commerce of the United States and Punish the Crime of Piracy.

The law described "the crime of piracy, as defined by the law of nations." Chief Justice John Marshall heard the case in Richmond, operating as a judge of the circuit court there. Sixteen prisoners were convicted, but Marshall and the other judge disagreed on whether the actions of the crew qualified as "piracy." Marshall noted:21

The case was elevated to the US Supreme Court for final resolution. It ruled that the US Congress was entitled to reference international law when defining the crime, and that the crew was guilty of piracy. All 16 were sentenced to death, but President Monroe reduced the sentences and none were executed.

The US Congress has not updated the 1819 law since the Supreme Court found it sufficient, but Federal judges still interpret it differently. In 2010, different Federal judges in the Eastern District of Virginia disagreed on whether two failed attempts to seize a US Navy vessel off the coast of Somalia qualified as piracy. One judge ruled that actual robbery had to occur before the 1819 law could be applied. The appeal resulted in a ruling that a violent attack, even if repulsed before robbery occurred, qualified as an act of piracy as understood under international law.22

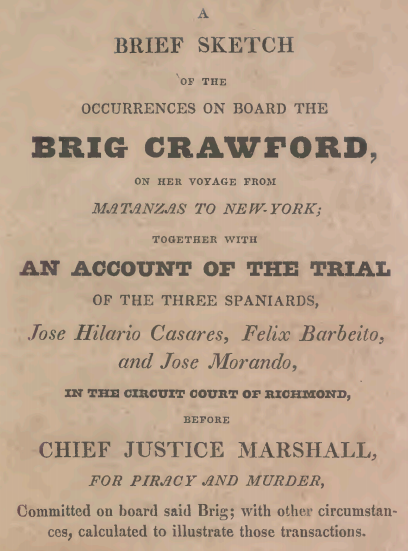

In 1827, three pirates were captured in Virginia, then tried and executed. They had helped to seize a vessel sailing from Cuba, planning to use it as a slave ship to smuggle human cargo from Africa to the United States. The pirates sailed to Norfolk to resupply before crossing the Atlantic Ocean. At Old Point Comfort, the pirates sent the ship's mate ashore to purchase supplies, but he immediately alerted the officers at Fortress Monroe. The head of the pirates killed himself, but three others fled in a boat to Hampton. They walked to Newport News, used a canoe to cross to the south bank of the James River, and got 20 miles inland before being captured.

Chief Justice Marshall opened a special session of the Circuit Court in Richmond for trial of the three men. The trial was conducted on July 16, 1827. The accused pirates were Spaniards from Cuba, so an interpreter was used to translate proceedings for them and to communicate their testimony.

The defendants claimed they had been asleep when the captain of the brig Crawford, most of the crew, and some passengers were murdered and tossed overboard near the Bahamas before the ship sailed to Norfolk. The jury returned three guilty verdicts after just five minutes of deliberation for each defendant, and they were executed within three weeks.23

in 1827, three pirates were tried, convicted, and executed in Richmond

Source: Library of Congress, A Treasure Trove of Trials

In 1856, as part of the negotiations at the end of the Crimean War, European nations signed the Declaration Respecting Maritime Law. It abolished privateering and the use of letters of marque. Private ships may still be converted to military use, but a government must accept responsibility for the actions of such vessels.24

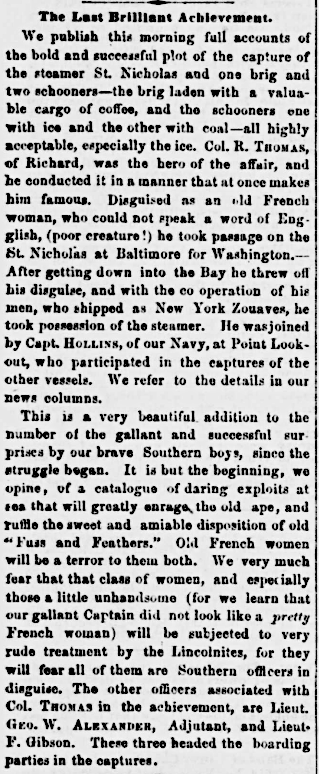

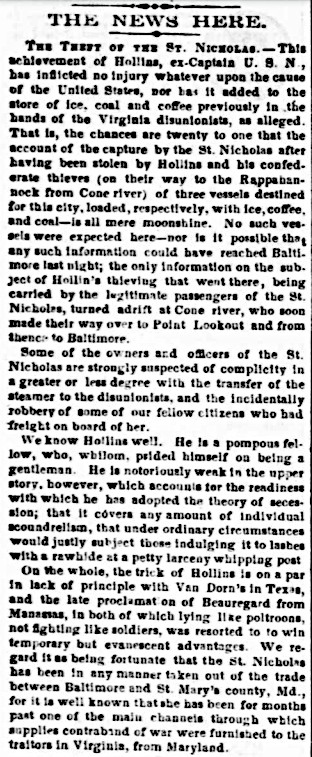

Confederates engaged in acts of piracy in 1861. The governor of Virginia sanctioned their plan to capture the USS Pawnee, then use it as a Confederate warship and disrupt Union shipping on the Chesapeake Bay.

The USS Pawnee commanded the three-ship Potomac Squadron that patrolled the Potomac River and interrupted smuggling between Maryland and Virginia. The Confederates planned to seize a packet boat, the St. Nicholas, which traveled regularly between Baltimore and the Patuxent River. That boat, pretending to still be under Union control, would be able to get next to the USS Pawnee.

The Confederate conspirators boarded the St. Nicholas as regular passengers. The commander was Richard Thomas, who adopted the last name of Zarvona. He got onboard disguised as a French lady, and inside her baggage trunks were weapons used to seize the boat. The St. Nicholas then stopped at the mouth of the Coan River in Northumberland County to unload passengers and crew, and to load 30 infantrymen sent by Governor John Letcher.

All three US Navy warships had returned to Washington, DC, so the Confederates had to settle for using the St. Nicholas to disrupt shipping in the Chesapeake Bay. There they captured ships loaded with coffee and ice, plus a coaling schooner which enabled a refueling while anchored in the Rappahannock River. The three captured ships and the St. Nicholas ended the pirate expedition by going to Fredericksburg. The 38 crew members of the four captured ships were taken by train to Richmond, then brought back to the Coan River and repatriated by a Confederate vessel to Point Lookout in Maryland.

After a legal proceeding in the Richmond District Court in Admiralty to determine the fair value of the St. Nicholas, the Confederate Government purchased the ship and delivered the funds to the owners in Baltimore. The ship was renamed the CSS Rappahannock, and burned to prevent recapture when the Confederates evacuated Fredericksburg in April 1862.

The Confederates tried to capture a second steamer, but ended up being caught. The Union Army did not give in to public demands to hang Richard Thomas Zarvona as a pirate, but also declined to consider him as a prisoner of war. His health deteriorated while imprisoned, and he was returned to Virginia as part of a prisoner exchange in 1863.25

a Richmond newspaper celebrated Confederate piracy in 1861, while a District of Columbia paper had a different angle

Source: Library of Congress - Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, The Daily Dispatch and Evening Star (July 2, 1861)

More recently, the wave of piracy in the Gulf of Aden off the coast of Somalia triggered trials in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. The first conviction in nearly 200 years was in 2010, for attacks on the USS Nicholas. By 2011, 26 pirates had been brought over 7,000 miles to Virginia for trial.

The largest group of pirates to be tried were captured in 2011, after Somali pirates with AK-47s and rocket-propelled grenades hijacked a 58-foot sailboat off the east coast of Africa. The American guided missile destroyer Sterett intercepted the seized Quest, but negotiations failed. The pirates executed the four American hostages on the sailboat. US Navy Seals swarmed onto the boat, killing four pirates and capturing 14 others.

Most pirates captured off the coast of East Africa recently have been tried in the courts of Somalia, Kenya, and the Seychelles. Because Americans were murdered on the sailboat, the US Navy brought the 14 captured pirates back to Norfolk for trial, where 11 pled guilty and were given life sentences. FBI and Somali security forces also captured the multi-lingual onshore negotiator, and after trial he was also given a life sentence.

The three pirates accused of shooting the Americans on the sailboat were tried in 2013 and faced the death penalty, but a Federal jury ended up giving them life sentences as well. One juror was apparently not convinced that the three men on trial were the ones who fired the guns and killed the four American hostages.26

When the Maersk Alabama was seized in 2009, the captain was held captive in a small lifeboat until Navy sharpshooters killed the pirates with him. The movie Captain Phillips, starring Tom Hanks, dramatized that event. Other pirates on the Maersk Alabama were captured and brought to New York for trial.

The pirates who had seized the Quest tried unsuccessfully to get their trial moved out of Norfolk. They contended:27

Virginia Gov. Alexander Spotswood send a military force into North Carolina in 1718 that killed the pirate Blackbeard

Source: Wikipedia, Blackbeard ("Capture of the Pirate, Blackbeard, 1718," painted by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris in 1920)

tourists can see a pirate ship sail by, cannon at the ready, at Hampton's annual Pirate Festival

Source: Watts, Hampton Blackbeard Pirate Festival Virginia ship cannon Adventure; Hampton Blackbeard Pirate Festival Virginia ships cannon

in 1718, Governor Spotswood offered a reward for anyone to capture or kill pirates

Source: A general history of the pyrates (1724)