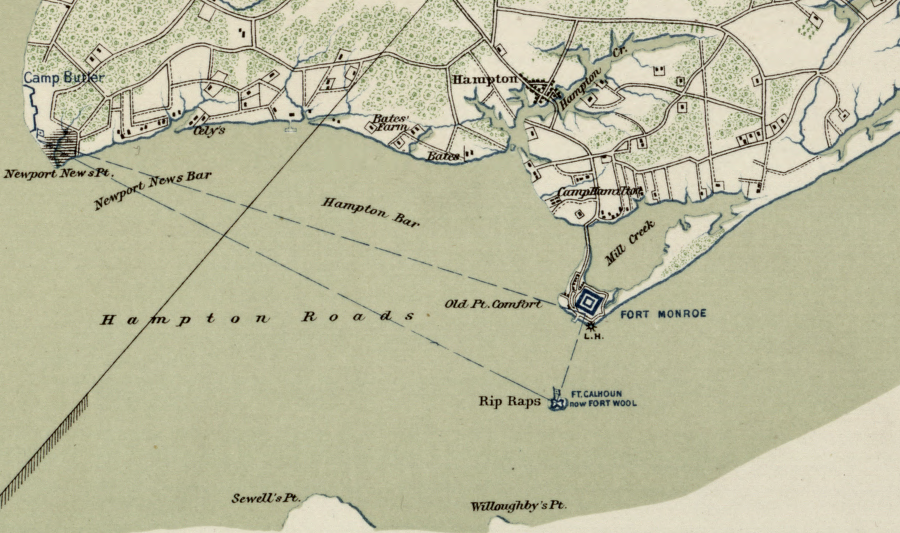

Fort Wool (originally named Fort Calhoun) was renamed in 1862 to honor General John Wool, the Union Army officer who captured Norfolk

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of the War of the Rebellion, Yorktown to Williamsburg, Va. (1892)

Fort Wool (originally named Fort Calhoun) was renamed in 1862 to honor General John Wool, the Union Army officer who captured Norfolk

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of the War of the Rebellion, Yorktown to Williamsburg, Va. (1892)

Until the Civil War, forts at Hampton Roads were unable to block enemy ships from sailing into the Chesapeake Bay or up the James River because cannon at shore batteries were not powerful enough to hit a ship in the channel.

In Hampton Roads, an enemy ship could sail near Willoughby Spit and be out of range from the artillery at Fort Monroe on the Peninsula. Through the Civil War, gunpowder lacked the "oomph" to push cannonballs all the way across the river. Enemy ships could navigate upstream while out of range of forts on either shoreline. Even if the gunpowder had been more powerful, the iron used for cannon barrels could not have contained and channeled the strong explosions.

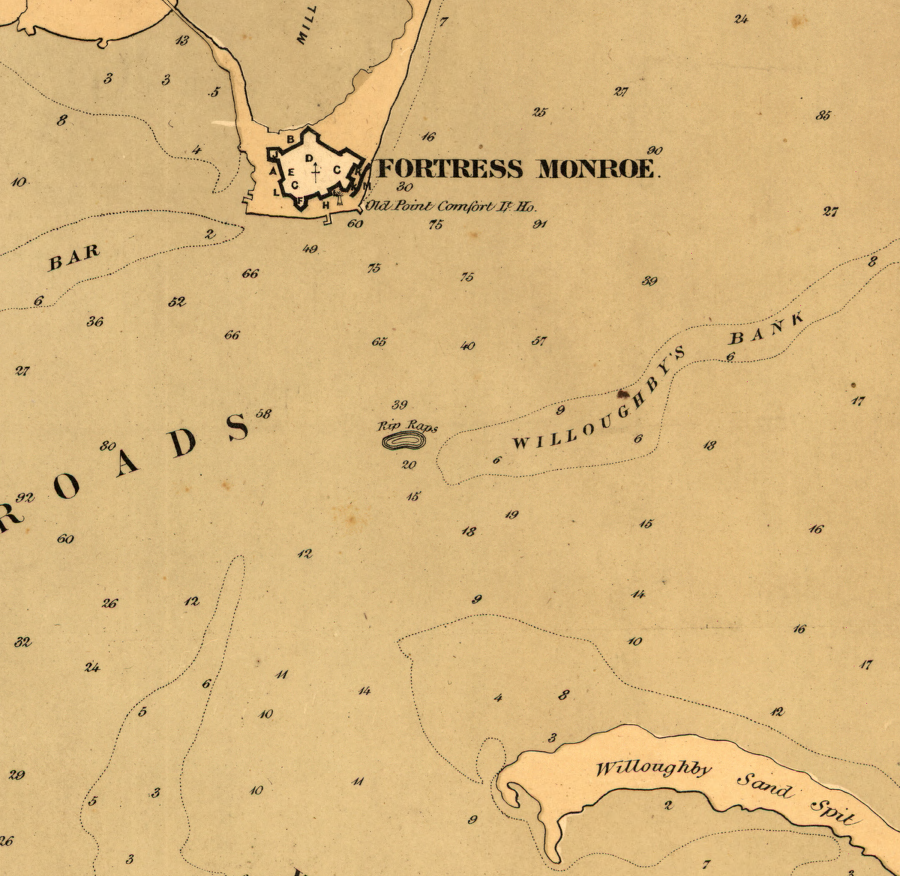

The solution was to manufacture a new island in the middle of Hampton Roads. Starting in 1818, the Americans sought to fortify the natural shoal called Rip-Raps (Willoughby Shoal) about halfway between Hampton and Norfolk. Rip-Raps got its name from the rippling of the water, as the Chesapeake Bay encountered a shallow deposit of silt, sand and clay off the Peninsula.

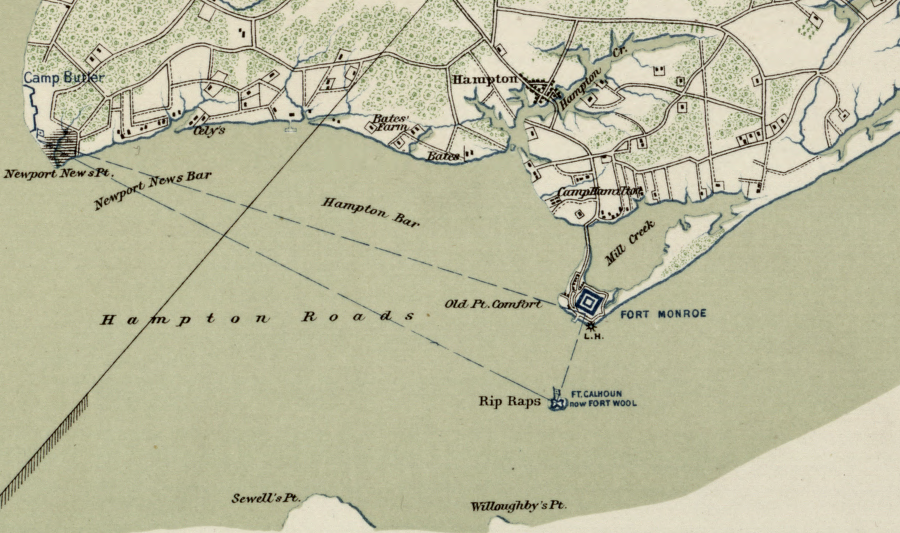

rock was dumped for decades on the Rip Raps shoal, before Fort Calhoun was finished and cannon could block ships from sailing up the James River

Source: Library of Congress, Preliminary chart of the Atlantic coast : from the entrance of Chesapeake Bay to Ocracoke Inlet (1862)

Rock hard enough to establish a foundation was available at quarries on the James, York, Potomac, and Susquehanna rivers. A contract was signed for "limestone" to be delivered from the York River. When it was found to be unsuitable, rock was obtained from quarries excavating the hard metamorphic rock near Georgetown on the Potomac River. Massachusetts granite quarries provided rock needed later for the drydock at Portsmouth Naval Yard.

Rock after rock was dumped onto the silty Rip-Raps shoal to create a foundation, or "mole" rising above the waterline. Cost of delivering the stone was high, in part because offloading it was risky. An 1822 Department of War report noted:1

The heavy stones sank into the soft sediments. After six years of adding stone, the army gave the site a year to settle before beginning construction of Fort Calhoun on the man-made island.

The military engineers quickly recognized that adding additional weight for that fort's granite walls increased the sinking of the artificial island. It dropped an additional six inches by 1831.2

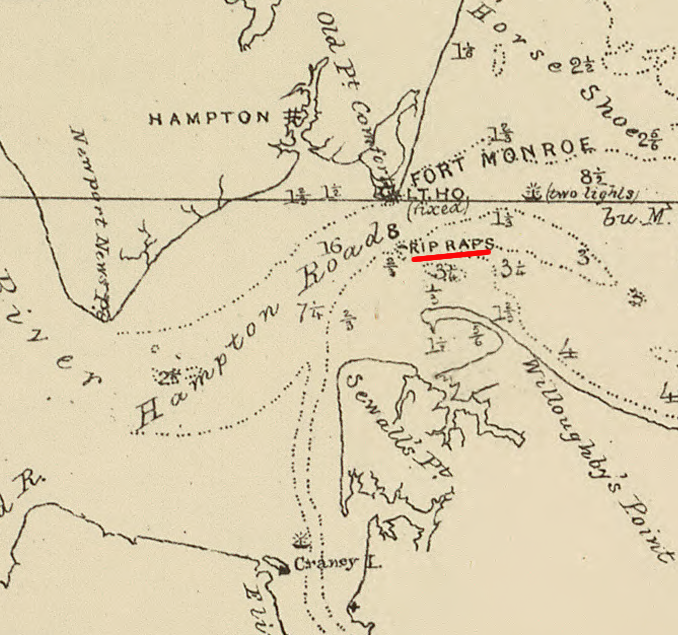

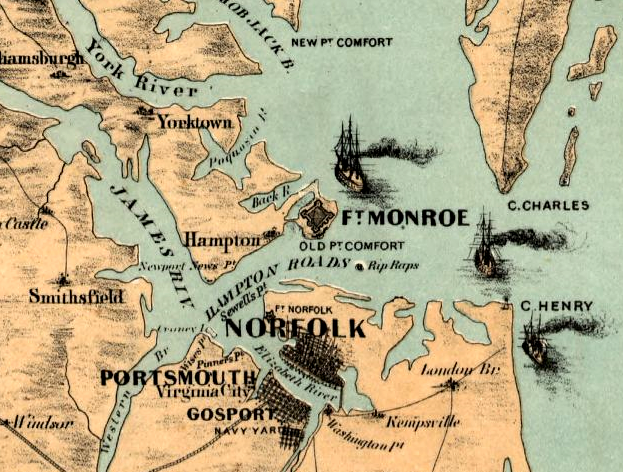

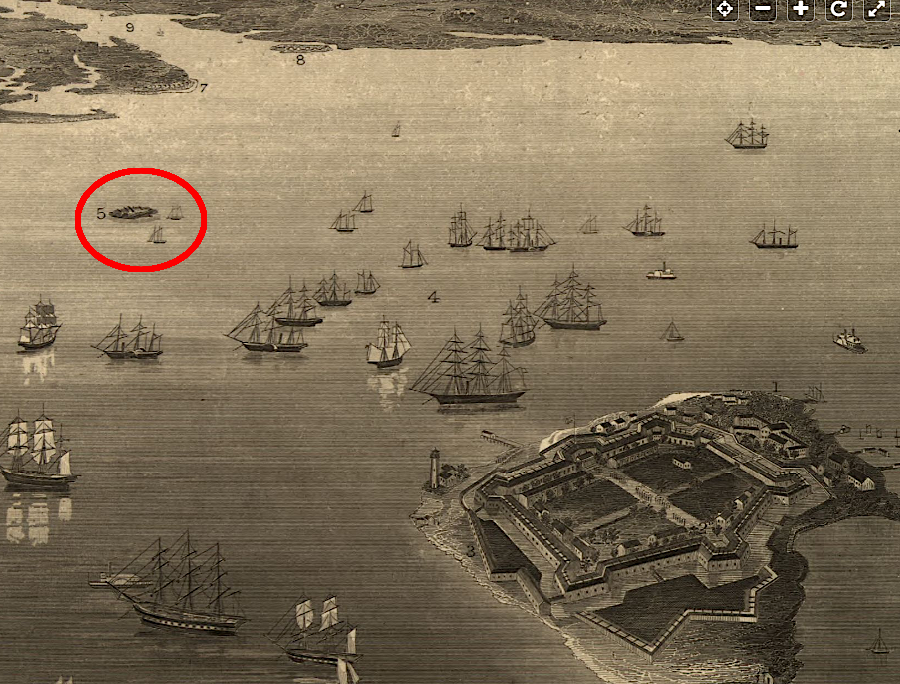

Fort Monroe and Rip Raps (site of Fort Calhoun, renamed Fort Wool) in 1861

Source: Library of Congress, Birds eye view of Virginia, Maryland, Delaware and the District of Columbia

The island kept sinking, and the plans for a three-story fort were altered. Stone walls with embrasures (openings) for cannon were completed only the northern side, facing the deep channel which enemy ships might use.

One of the enslaved men who worked on the island was Shepard Mallory. At the start of the Civil War, he fled with two other enslaved men to Fort Monroe. Union General Benjamin Butler made a momentous decision when he refused to return them to the slaveowners, and instead declared the three men "contraband of war" to be retained within Union lines.3

Fort Calhoun was still not finished when Virginia seceded from the Union in 1861, but it was protected by the cannon at Fort Monroe and the Confederates could not assemble a fleet of warships strong enough to force its abandonment.

At the start of the Civil War, Confederates controlled the southern edge of Hampton Roads, including Willoughby Spit, Sewells Point, and Craney Island. That enabled Confederate warships to move from the Gosport Navy Yard down the Elizabeth River, and travel upstream to Richmond.

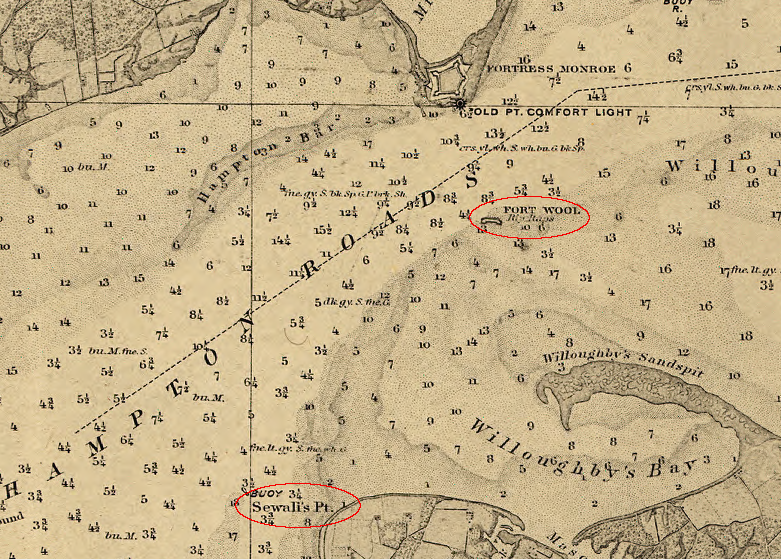

Fort Wool, at the start of the Civil War, was a small but essential barrier to ships entering/leaving the James River

Source: Library of Congress, Fortress Monroe, Va. and its vicinity (by Jacob Wells, c.1862)

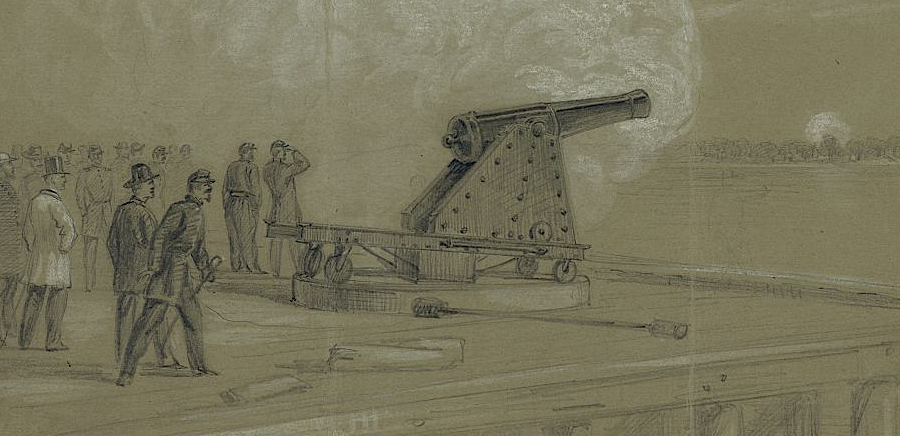

However, Confederate ships that tried to move eastward from the Elizabeth River towards the Atlantic Ocean came within range of the Union-held fort on Rip-Raps shoal. The largest Yankee rifled cannon (the Sawyer gun) had sufficient range even to reach the Confederate fortifications across Hampton Roads at Sewells Point, now the location of the Norfolk Naval Base, home bases of nuclear-powered aircraft carriers.4

Fort Calhoun (Rip-Raps) and Fort Monroe in distance, as seen from southern shoreline of Hampton Roads

Source: Harpers Weekly, Virginia Sketches (April 6, 1861)

Fort Calhoun was renamed Fort Wool in 1862, shifting the honor from a South Carolinian who advocated secession to the Union General, John Wool, who finally captured Norfolk on May 9, 1862. Three months after the Monitor and the Virginia had dueled to a draw on March 9, General George McClellan used Fort Monroe as his staging base to support the Union army on the Peninsula. He finally marched to Williamsburg, but General McClellan was an Army officer, and ignored the threat of the Confederates in Norfolk and the warship the Virginia across the James River.

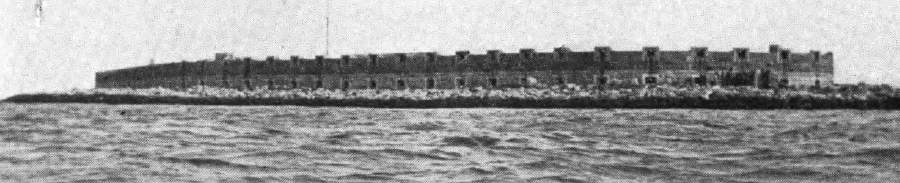

the first version of Fort Wool included masonry parapets and casemates

Source: Round about Jamestown: Historical Sketches of the Lower Virginia Peninsula (p.21)

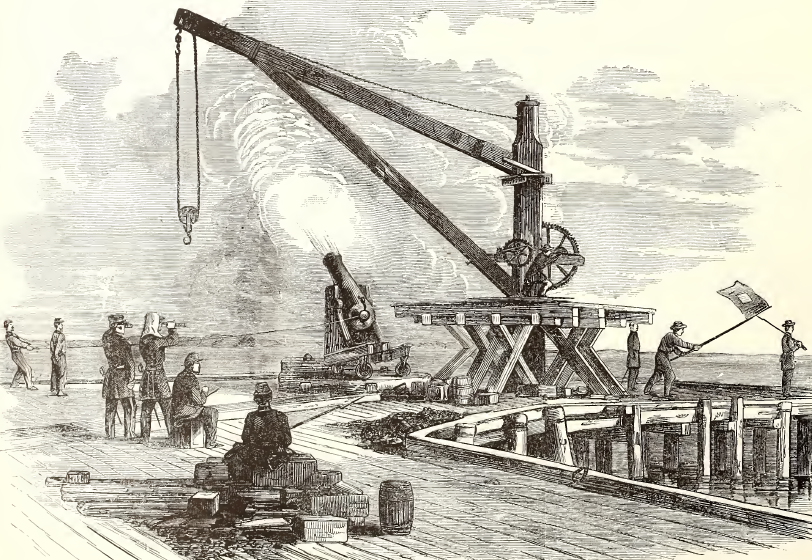

from Fort Wool, the Union forces could harass the Confederates on Sewells Point with the Sawyer gun

Source: Frank Leslie's Illustrated History of the Civil War, Practicing With the Celebrated Sawyer Gun On the Confederate Batteries at Sewell's Point, Near Norfolk, VA, From Fort Calhoun, On The Ripraps, in Front of Fortress Monroe

(p.243)

Abraham Lincoln is credited with directing the Union Army and Navy to cooperate to capture Norfolk and force the destruction of the Virginia.

Union guns fired from Fort Wool across the James River to destroy Confederate batteries on Sewell's Point

Source: Library of Congress, Scene on the dock at the Rip Raps. Testing the Sawyer gun and projectile (by Alfred R. Waud, 1861)

After President Lincoln arrived at Fort Monroe and proposed capturing Norfolk, the Union Navy ferried 6,000 troops past Fort Wool to Ocean View east of Willoughby Spit. Norfolk surrendered quickly, and the Confederates burned the Virginia because the James River upstream of Newport News was too shallow for the ship weighted down with iron. The military value of Fort Wool declined after that event, and it was essentially abandoned until after the Spanish-American War.

during the Civil War, cannon at Fort Wool hit Confederate fortifications at Sewells Point but caused minimal damage

Source: Library of Congress, Chesapeake Bay, Sheet no. 1, York River, Hampton Roads, Chesapeake entrance

After the Spanish-American War renewed concerns about defending the United States from European threats, the military rebuilt Fort Wool between 1902-1908. Using the Endicott Plan for seacoast fortifications, much of the stone fort was removed and rifled "disappearing" guns were installed. The primary role of the fort was harbor defense, protecting a minefield that would be deployed if enemy ships arrived near the East Coast. In World War II, mines were placed at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay (by both Germans and Americans...) and an anti-submarine net was anchored on Fort Wool.5

after the Spanish-American War, masonry was stripped from Fort Wool and guns/radar installed so it could protect minefields and submarine nets in Hampton Roads

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Nomination of Fort Wool to National Register

Fort Wool, today

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 170428-A-BJ79_33

Like Fort Monroe, the Virginia General Assembly gave the United States the right to use the land at Fort Wool in 1821, but included a reversionary clause to return the property to the state if no longer needed. The military decommissioned Fort Wool in 1953, and formally returned it to the state in 1967.

The state leased the island to the City of Hampton and then transferred ownership to the city in 1985. Hampton tried to make Fort Wool into a visitor attraction, though the only access was via a tourist boat. The fort is connected to an artificial island constructed for the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel in 1957, but there is no parking for the public on that island. Even the boat access was eliminated for three years after 2003, until damage to the dock caused by Hurricane Isabel was repaired.6

Fort Wool is connected to the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, but there is no visitor access except by boat

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Boat access was closed again for safety reasons after 2017, ending visits by the Miss Hampton II tour boat. In 2020, The state cancelled the lease to the City of Hampton and chose to use the island for a different purpose. Fort Wool was dedicated to bird habitat, as mitigation for expansion of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel. The island's 1.5 acres were transformed into nesting bird habitat.

To construct two new tunnels and double the capacity of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, the Virginia Department of Transportation paved over 10 acres of open space on the existing tunnel's South Island. Converting the open sand on the island to asphalt eliminated nesting habitat for roughly 25,000 terns, gulls, and black skimmers. To replace the largest waterbird nesting site in Virginia, the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries removed grass, trees and shrubs from the parade ground, added extra sand there, and killed the rats to create a safe site for young chicks.

The conversion also required turning off the lights which were shining at night on a massive, 20' x 38' American flag, which had been displayed on a 90' high pole all day and night starting in 2007. The flag was removed in an honor guard ceremony before the birds migrated back from Central and South America.7

Starting in 2020, the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (later renamed the Department of Wildlife Resources) utilized barges as well as Fort Wool for bird habitat. The barges and the parade ground at Fort Wool provided no more than 2.5 acres of nesting area, just 25% of the nesting area formerly available on South Island.

The state agency also planned for construction of a new island dedicated to bird conservation. Advocates for preserving Fort Wool as a historic military installation encouraged removal of the sand and restoration of the site, as soon as possible. In 2021, the Coalition for Historic Fort Wool exerted public pressure to ensure use of Fort Wool would be only a temporary situation. The historical preservation advocates noted that state officials:8

Fort Wool, sometime between 1900-1915

Source: Library of Congress, Fort Ripraps, Fortress Monroe, Va.

After four years of exclusive bird use, the Hampton City Council began pressing state officials to reopen Fort Wool for public visits. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources estimated in 2024 that an artificial island to provide bird habitat would cost $10 million. To make that project more cost-effective, it was designed to use sediment dredged to create a new anchorage for ships. Constructing a temporary parking spot for ships, to be used until a slot at a shipping terminal opened up, would generate the material needed to manufacture a new island.

Hampton city officials anticipated that the state would cover the costs to restore Fort Wool before offering a new lease for the city, and the city would arrange for public visits.9

the large flag which flew 24-7 at Fort Wool since 2007 was removed in 2020, to make the island suitable for bird nesting

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Ft. Wool Flag Decommissioned

the Sawyer Gun at Fort Calhoun could reach Confederate fortifications at Sewells' Point

Source: Harpers Weekly, The Rebel Batteries On Sewall's Point And Craney Island (November 2, 1861)

in 1845, Fort Calhoun was operational and extended the range of cannon beyond the reach from Fort Monroe

Source: Historical collections of Virginia, Fort Monroe is seen in front, on Old Point Comfort, and in the distance, Fort Calhoun, at the Rip-Raps (p.253)

dredging operations to maintain the shipping channel between Fort Monroe and Fort Wool have some visual impact on the visitor experience

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk Harbor Navigation Improvements - Draft General Reevaluation Report and Environmental Assessment (Figure 2-40)

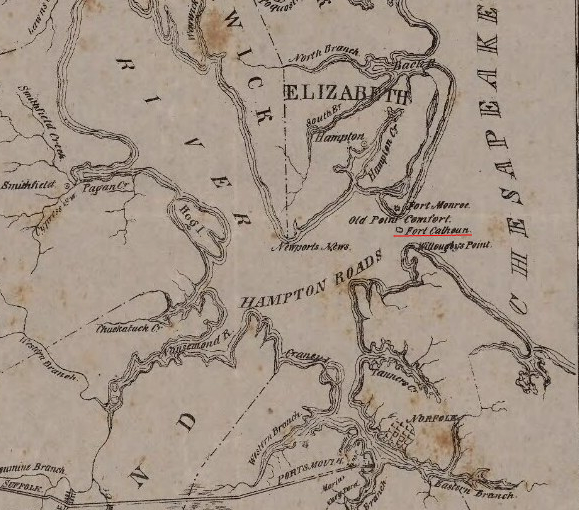

Rip-Raps shoal is located between Willoughby Spit and Point Comfort

Source: Library of Congress, The key to East Virginia (1861)

Fort Calhoun, around 1840

Source: University of Virginia, Plan of the Portsmouth and Roanoke Rail Road