building the first fort at Jamestown, May-June 1607

Source: National Park Service, Jamestown - Sidney King Paintings Gallery

building the first fort at Jamestown, May-June 1607

Source: National Park Service, Jamestown - Sidney King Paintings Gallery

The English faced two threats when they landed at Jamestown, fellow Europeans and Native Americans. At the start of colonial settlement, the Europeans were perceived as the greater threat. That was a mistake.

The Godspeed, Discovery, and Susan Constan sailed upstream past the mouth of the James River, and the colonist eventually decided to settle on Jamestown Island. John Smith complained that building military defenses there to protect against attack by the Native Americans was delayed by the President of the Council, Edward Maria Wingfield. Wingfield may have been trying to comply with instructions from the Virginia Company in London to maintain peaceful relationships with the "naturals," who were a potential source of food and information about the territory and its resources.

The Virginia Company's instructions were:1

Smith accused Edward Maria Wingfield in Jamestown of delaying construction of fortifications for reasons other than diplomacy. According to Smith, who was not an ally of Wingfield, the first President of the Council was excessively concerned about his personal authority. Wingfield had not proposed fortifying the English camp on Jamestown Island. It was not his personal idea, and he refused to take advice from others on the Council.

Captain George Kendall did manage to create a low barrier of tree branches that marked the boundary of the encampment:2

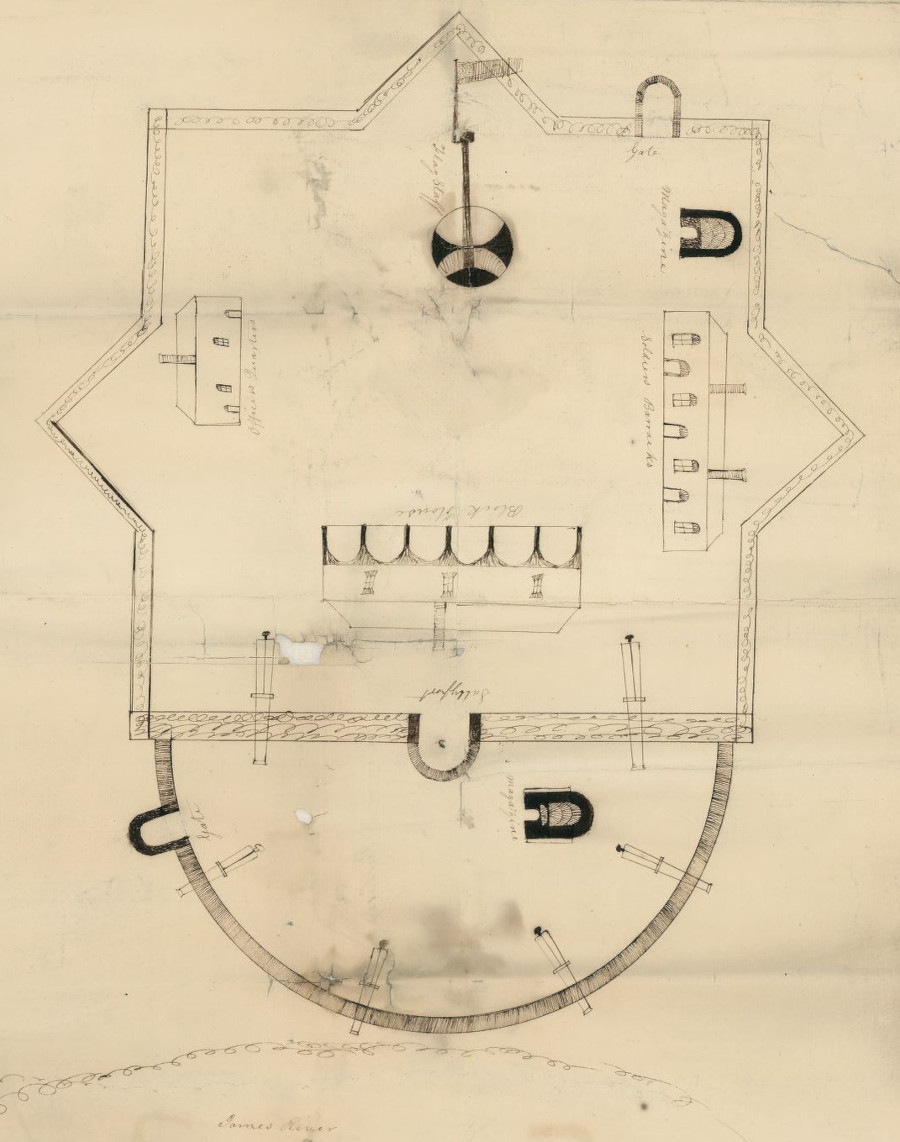

An attack by the "naturals" in which a young boy was slain forced a change of mind. The colonists repelled the assault only after cannon fire from a ship frightened the Native Americans into retreat. Wingfield quickly ordered construction of a wooden palisade, and within three weeks the English had finished their first fort. It had one wall of tree trunks 120 yards long facing the river, and two other walls 100 yards long:3

Building a fort that was more robust than "boughs of trees" was consistent with another part of the instructions. The Virginia Company had directed that 30 of the colonists should be assigned to build fortifications and storehouses.

In 1607 a second structure was built near Point Comfort, but probably not at the future location of Fort Monroe. The second English fort in Virginia was probably on Strawberry Banks or closer to Hampton Creek, where there was easier access to drinking water.

That fort housed colonists who provided an early warning system to spot arriving ships. It was not a sturdy fortification cabable of withstanding attack by a European warship with cannon. Ten colonists (10% of those in Virginia) were directed to stay at Point Comfort, in compliance with Virginia Company guidance:4

Fort Algernourne (and later Fort Henry, Fort Charles, Fort George, and Fort Monroe) was built on Point Comfort after the colonists displaced the Kecoughtans from their village

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith, 1606

model of 1607 James Fort, a triangular wooden structure with half-moon bastions at each corner where cannon were placed on raised platforms

The choice of the location for Jamestown so far upstream from the mouth of the James River, and the construction of a fortification ("stoure") for ten men at Point Comfort, were shaped by fears of European attack. A member of the Nansemond tribe succinctly noted in 2004, during the preparations for commemorating the 400th anniversary of Jamestown:5

That comment may gloss over the legitimate concerns of the first English colonists regarding the Native Americans, but the Spanish, Dutch, French, and even pirates were serious threats from the Atlantic Ocean. The Spanish did prepare to send ships to attack Jamestown in 1608, but then diverted them to the Netherlands.6

Locating the first settlement at Jamestown, upstream of Hog Island, ensured that anyone sailing up the river would be clearly visible before they could reach the English. A European ship would have to fight the river current and tack multiple times to reach Jamestown. That would give the English time to gather everyone inside the palisaded fort and to defend it with their cannon and muskets.

The 1607 structure at Point Comfort was equivalent to the Distant Early Warning (DEW) system constructed in Canada during the 1950's to spot intercontinental ballistic missiles launched by the Soviet Union, and to give American officials in Washington DC an opportunity to respond. The shipping channel to go up the James River was on the northern side of the river, so the fort's cannon did have some ability to deter upstream travel by enemy ships.

Point Comfort was an isolated, barren, wind-swept location for the 10 or so colonists stationed there. The English first visited Point Comfort in April, 1607, just after the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery arrived. The English applied the name "Point Comfort" to the tip of the Peninsula because the deep river channel there ensured easy access by boat.

When they first arrived:7

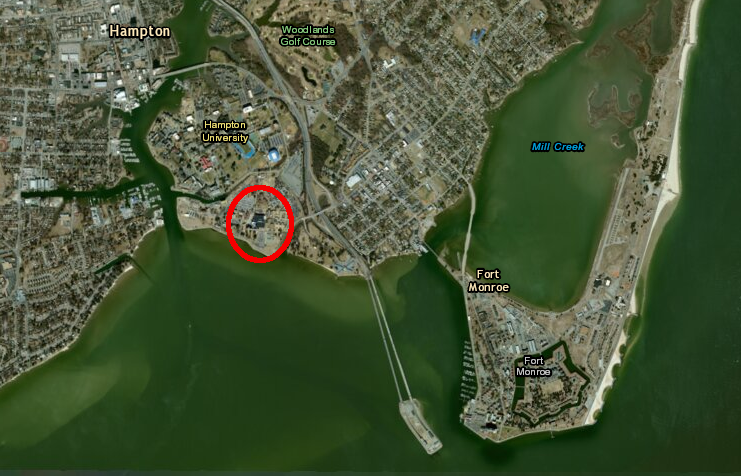

The "little stoure at the mouth of the river" (Point Comfort) was close to the town on the Hampton River occupied by the Kecoughtan tribe. The site of Kecoughtan is thought to be near the current Veterans Administration Building in Hampton.

John Smith reported that there were 18 houses in the Native American town, scattered across three acres. He had to threaten to use force in order to compel the Kecoughtans to trade for food earlier in 1607, but relations were peaceful for the next two years. Powhatan did not order the Kecoughtans to expel the English from their new fort at Point Comfort.

The paramount chief's strategy was to trade with the English rather than expel then. Powhatan's military capacity at the tip of the Peninsula were limited, in part because he had just conquered the Chesapeakes and taken control of what today is the City of Virginia Beach, but his warriors could easily have killed 10 Englishmen.

Powhatan had more resources further upstream, and he used them differently than at Point Comfort. English attempts to establish a settlement at the Fall Line, near the site of Richmond today, were repulsed in 1609. The colonists directed by John Smith and later George Percy to that location were deep in Pamunkey territory, where Powhatan had more warriors.

The colonists sent upstream from Jamestown made it easy for Powhatan to use force. The English failed to build palisades, so they were exposed to constant sniping from the Native Americans. John Smith visited and tried to improve the defense. He proposed moving the English encampment to a better location, but his direction was ignored. Smith may have been so undiplomatic when proposing action that even very good ideas were rejected.

The colonists at the Fall Line encampment never built a fort there. They ended up abandoning their site under pressure from the local Native Americans and returned to Jamestown, where they suffered through the 1609-10 Starving Time.8

In 1609 George Percy became president of the colony. John Smith's term ended in September, and he returned to England in October. Percy ordered the construction of Fort Algernourne (also spelled Algernon) near Point Comfort and increased the number of colonists stationed there. Fort Algernourne was built at the mouth of the Hampton River.

The new, larger fort was not intended to be a major defense installation. Percy did not demand that the Virginia Company's indentured servants and soldiers build strong walls, ditches, and embankments compable to a fortress in Europe. It could not staff a fort with a critical mass of soldiers able to withstand assault by European warships or pirates. The fort remained part of a distant early warning system.

As a defense installation, Fort Algernourne primarily was intended to provide intelligence to Jamestown regarding new ships arriving in the Chesapeake Bay. The settlers there could have provided fish and seafood to colonists at Jamestown. In 1609, after the arrival of most ships in a convoy that had been scattered by a hurricane, Jamestown had too many colonists to feed from the available supplies.

As described by George Percy:9

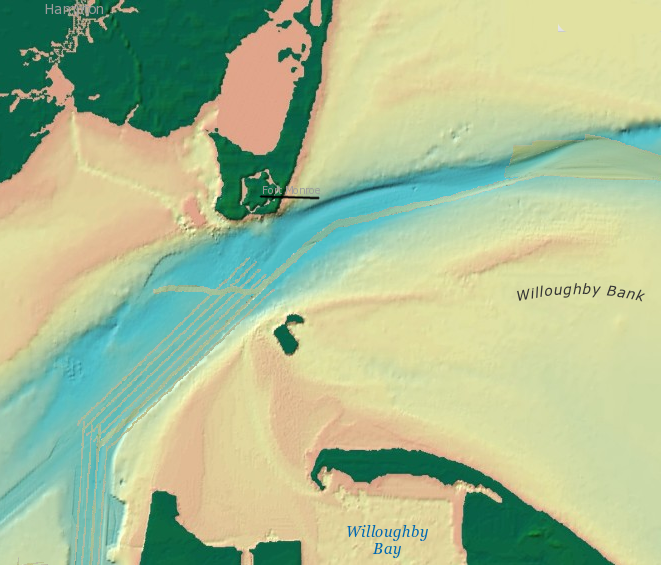

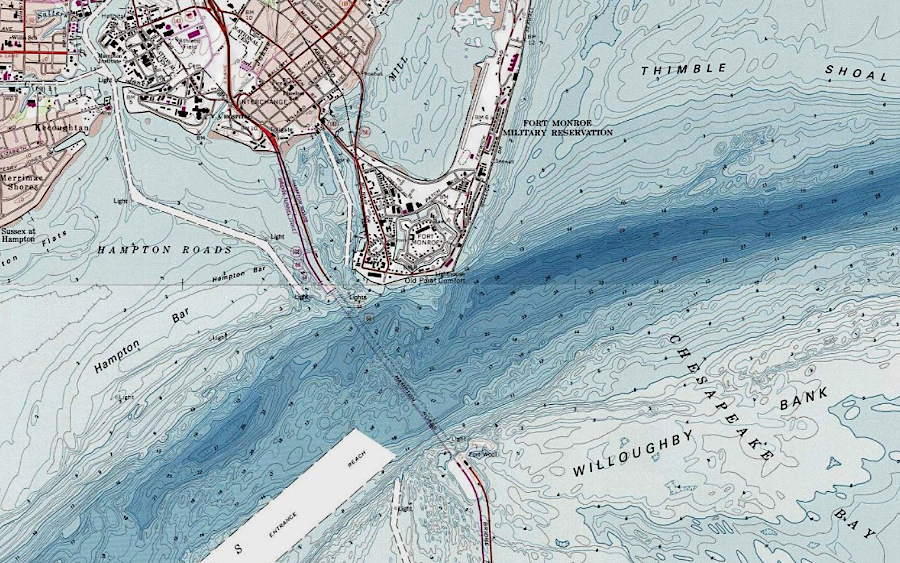

the shipping channel is close to Point Comfort/Fort Monroe

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Geophysical Data Center; ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Percy named Fort Algernourne after his older brother, who had inherited the family wealth and title. The Fort Algernourne oak at Fort Monroe, reputedly 500 years old, commemorates that first fort.

the Algernourne Oak started growing almost a century before the first English colonist reached Point Comfort

Source: National Park Service, Algernourne Oak

Captain James Davis commanded the 30 colonists who spent the winter of 1609-10 at Fort Algernourne. They survived far better than the colonists at Jamestown who ran out of food during the Stariving Time. Captain Davis never sent fish, crabs, oysters, or other readily-available seafood upstream that winter to supply the main settlement, where most of the colonists died from disease due to starvation. Apparently no ships traveled up or down the James River during the entire Starving Time; the two groups of colonists were completely out of touch.

When Percy finally visited Fort Algernourne in the spring of 1610, he accused Captain Davis of hiding the healthy conditions there. Percy claimed that Davis was hoarding food. His men had been feeding their surplus crabs to fatten hogs, rather than sharing food with those who were starving upstream at the Jamestown fort. Percy though the few colonists at Fort Algernourne were planning to abandon Virginia and escape back to England:10

Fort Algernourne at Point Comfort was 35 miles downstream (by water) from Jamestown

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The first ships spotted by the guards at Fort Algernourne in 1610 were the Patience and Deliverance. Those two small ships had been constructed at Bermuda from the wreckage of the Sea Venture.

The Sea Venture, the flagship of the 1609 convoy, had been commanded by Christopher Newport and carried Sir Thomas Gates to serve as the new governor of the colony. A hurricane separated the flagship from the other ships in the Third Supply fleet, and the Sea Venture wrecked on Bermuda. Over the winter, resourceful English sailors constructed two pinnaces to carry the 150 stranded colonists from Bermuda to Virginia.

When the Deliverance arrived off Point Comfort on May 21, 1610:11

After arriving from Bermuda in 1610, Sir Thomas Gates ordered a series of assaults on Native American towns along the James River. The colonists expelled the Kecoughtan tribe from their town on the Hampton River and occupied the site. The Kecoughtans fled north across the York River to territory once occupied by the Piankatank tribe.

The already-cleared land of the Kecoughtans gave the colonists a head start in growing corn in 1610 and becoming more self-sufficient in food. Expelling the Kecoughtan tribe also complied with the original 1606 instructions from the Virginia Company to remove the native people of the country who inhabited land between Jamestown and the sea coast.12

After he arrived in 1610, Lord de la Warre ordered construction of Fort Charles and Fort Henry near the site of Fort Algernourne. Upstream from Jamestown, he also ordered construction of Fort West at the Fall Line. Fort West, named after Lord De la Warre's family name, would allow expanding the edge of English settlement to the west.

Fort Charles was built on the Strawberry Banks, just west of where modern I-64 leaves the solid land of the Peninsula and goes south on piers and into a tunnel underneath the mouth of the James River. Fort Henry was built near modern Hampton University, on the east side of the Hampton River.

Fort Charles and Fort Henry guarded the entrance of the Hampton River, but may have been intended primarily to defend against an attack by Powhatan in retaliation for expelling the Kecoughtans. The forts provided shelter for colonists if a war party came to destroy the colonists' fields of corn. John Smith suggests another possibility: the forts were designed primarily as rest stops for new immigrants arriving from England to recover from the journey before moving upstream.

When Sir Thomas Dale arrived in 1611, he assigned people to live at Fort Charles and Fort Henry and grow corn. Continuous colonial occupation of Kecoughtan, later part of Elizabeth City County and now the City of Hampton, dates to Dale's decision. The site is the oldest location in North America that has been permanently settled by the English.13

the town of the Kecoughtans seized by Sir Thomas Gates in 1611 is now part of urbanized Hampton, perhaps where the Veterans Administration is located

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Labor was scarce in the early days of the colony, so the investment in fortifications at Point Comfort was limited. The Spanish ship the Nuestra Senora del Rosario arrived at Point Comfort in June 1611. Captain Don Diego de Molina claimed his ship had been blown off course and was not hostile. However, when the English started to row out to it into order to guide the ship into a safe anchorage in the James River, the Nuestra Senora del Rosario sailed away. The captain was left ashore, along with two others.

While in captivity Diego de Molina managed to smuggle a message to the Spanish ambassador in London in 1613. He reported that the three fortifications at the tip of the Peninsula (Forts Algernourne, Charles, and Henry) would offer little resistance to a Spanish attack:14

Diego de Molina was sent back to England finally in 1616. He wrote a letter with military intelligence on June 14, 1614 and somehow managed to get it delivered to the Spanish ambassador in London. In the letter de Molina reported:15

When Diego de Molina was abandoned in 1611, the Nuestra Senora del Rosario had left withb an English pilot on the ship. John Clark had expected to guide the Spanish vessel closer to shore, but ended up a captive until exchanged five years later for Diego de Molina. In a Spanish interrogation, Clark reported:16

Fort Algernourne burned accidentally in 1612. Forts Charles and Henry decayed, but the English continued to live on the Peninsula at Hampton. Ships arriving from trans-Atlantic trips would stop there to obtain fresh water and food, and to identify their peaceful intent in order to receive clearance for entering the colony.

In 1619, a year before the colonists renamed Kecoughtan as "Elizabeth City" (and later Hampton), an privateer sailed into the Chesapeake Bay with a new cargo. The White Lion was flying the Dutch flag, but had been financed by the Duke of Savoy in France. In the Gulf of Mexico, it had captured a Spanish slave ship carrying Angolans to Mexico. To sell that cargo, the privateer went to the nearest market beyond the boundaries of Spanish occupation. The first slaves brought to the new English colony in Virginia landed at Point Comfort.16

John Rolfe reported in a letter back to the Virginia Company in London:17

In that same letter, he provided a report on the weak condition of the fortifications at Point Comfort and the colony's exposure to attack by the Spanish:

Another fortification was built in 1630-1632 at Point Comfort. The wooden walls of the "Point Comfort fort" decayed in the humid climate from lack of maintenance.

In the 1640's Governor Berkeley wanted to build a new fort and wanted it to be located at Jamestown, not at Point Comfort. Placing the fort at the capital would facilitate the collection of duties (tariffs) and issuance of licenses for ships sailing into or leaving the colony. The English Civil War intervened. Berkeley was deposed as governor and not reinstated until 1660.

During the Anglo-Dutch wars in the 1660's, the Virginia colony did try to build a fort at Point Comfort. A 1667 hurricane washed away the construction materials before the new fort was completed.18

The additional taxes imposed on all colonists to defray the costs for that failed fort were unpopular, and one factor that led to Bacon's Rebellion in 1676.

Forts at Jamestown and Point Comfort provided no protection against the greatest threat to settlers in the backcountry, the risk of a Native American attack. After Bacon's Rebellion, grievances collected from Nansemond County included the complaint that taxes to build forts on the frontier were used to construct structures that would become houses for the wealthy. The conventional wisdom in the backcountry was that mobile rangers were needed, not forts which war parties could easily bypass:19

slaves first arrived in Virginia at Point Comfort in 1619

Source: National Park Service, Africans in the Chesapeake

Absence of Chesapeake Bay fortifications left the colony undefended in 1667 and again in 1673. Dutch raiders were able to sail through Hampton Roads without being disturbed by any cannon on the tip of the Peninsula or elsewhere. After the Anglo-Dutch wars concluded, the General Assembly authorized constructing a fort at Norfolk. It was to be built in the shape of a half moon at Four Farthing Point, now known as Town Point.

The new Norfolk fort was completed by 1680, but it was not maintained. Today's Half Moone Cruise and Celebration Center at Town Point is named after the 1680 fort.20

Reportedly there was a battery constructed at Point Comfort in 1711, but only in 1728 did the English commit the resources to build a new fort there. By that time, fear of Spanish attack had been replaced by concerns regarding the French. Governor William Gooch and the General Assembly agreed to build Fort George at Point Comfort. According to one report (written a century later), the outer brick wall was 27" thick, the interior brick wall was 16" thick, and there was 16" of earth fill between those brick walls.21

Fort George was washed away by the great hurricane of 1749, the same storm that created Willoughby Spit. No fortifications were constructed at Point Comfort during the French and Indian War/Seven Years War between 1756-63 (though fighting started in Virginia in 1754). The threat at that time was invasion on the western edge of the colony. That threat was diminished when Fort Duquesne on the Ohio River (now the site of Pittsburgh) was captured in 1758.

the 1755 Fry-Jefferson map of Virginia noted the location of Fort George at the tp of the Peninsula, even though the structure there had been eroded away during a 1749 hurricane

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1755)

the 1755 Fry-Jefferson map of Virginia also indicated that two forts guarded the mouth of the York River

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1755)

On October 26, 1775, British ships fired on the town of Hampton in "the first battle of the Revolutionary War south of Massachusetts." The small British craft were forced to retreat by rifle fire from American rebels on the shoreline, not by any cannon at a Point Comfort fort.22

When Benedict Arnold led the British invasion of Virginia in January, 1781, there were still no effective American defenses along the James River. Arnold's force landed at Westover without harassment, marched 30 miles to Richmond, and burned the public buildings and warehouses on January 5, 1781. Governor Thomas Jefferson watched the fires helplessly from across the James River in Manchester.

The British returned to Richmond again in May, 1781, forcing the General Assembly and governor to flee to Charlottesville and ultimately further west to Staunton. The absence of defensive forts blocking the shipping channels at Hampton Roads allowed the British invaders to move deep into the interior of Virginia.

The state capital had been moved in 1780 to Richmond from Williamsburg, which was easily accessible from British ships sailing up to College Creek on the James River or Queen's Creek on the York River. Since the Virginians had no defensive fortifications in Hampton Roads, Lord Cornwallis was resupplied at Portsmouth and able chase the members of the General Assembly out of Charlottesville in 1781.23

At the end of the American Revolution, the British had an opportunity to build a fort at Point Comfort. General Cornwallis declined to use the site; he chose to fortify Yorktown instead. In contrast to Point Comfort, Yorktown offered existing structures for shelter, easier access to drinking water and construction materials, and an equally-accessible deepwater port for the expected resupply fleet from New York.

French engineers who came to Yorktown in 1781 identified the old site of Fort George, even though there were no effective fortifications there

Source: Library of Congress, Carte de la partie de la Virginie ou l'armee combinee de France & des Etats-Unis de l'Amerique a fait prisonniere l'Armee anglaise commandee par Lord Cornwallis le 19 octobre. 1781

Point Comfort remained undefended until after the War of 1812, when the British destroyed Hampton and sailed unhindered through Hampton Roads and the Chesapeake Bay. Starting in 1816 the US Congress began to fund the Third System of forts. Fort Monroe, the first and largest of the Third System forts, was built at Point Comfort between 1819-1834. All Third System forts were large masonry structures based on French designs, rather than the earth-and-wood structures previously built by the colonists.24

The cannon at Fort Monroe (with assistance from cannon on an artificial island originally named Fort Calhoun) provided effective defense against enemy attack through World War I. Fort Monroes remained an active military base until the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Commission decided in 2005 to close it.

The closure of Fort Monroe was completed in 2011. There are no longer any active military installations on Point Comfort.

Fort Powhatan on the James River, after the War of 1812

Source: Library of Congress, lan of Fort Powhatan, Prince George County, Virginia (by Elijah Brown, 1819?)

the location of Fort George was included on a 1781 English map of the Yorktown battlefield

Source: Library of Congress, A Plan of the entrance of Chesapeak Bay, with James and York rivers

the French map in 1781 made clear that Fort George was demolished

Source: Library of Congress, A Plan of the entrance of Chesapeak Bay, with James and York rivers

by the Civil War, a causeway linked the tip of Point Comfort with the mainland

Source: Library of Congress, The Union army encampment at Hampton, Virginia Showing picket lines and Fortress Munroe