water in Bull Run rose above its normal channel and spilled onto the floodplain at Manassas Battlefield, May 2014

water in Bull Run rose above its normal channel and spilled onto the floodplain at Manassas Battlefield, May 2014

The shape of a river channel reflects the pattern of the waterflows than run down through that channel, as well as the rock through which the water has carved its path. The width and depth of stream channels is determined by the amount of water carried by the stream after a 2-year flood (the rainstorms with a 50% chance of occurring). Floods occur when the volume of the river channel is not sufficient to contain the runoff from bigger storms.

A river will carve a channel with clearly-defined banks on each side, in most cases. During occasional floods, the water level will rise to fill the channel. Newspapers may describe the river as running "full to the banks," but the river does not reach flood stage until it rises higher than the river banks and water spills over onto the adjacent land.

Youngs Branch at Manassas National Battlefield Park, "bankfull" after rains throughout July 2018

When the floodwaters spread out on the floodplain adjacent to the stream channel, the water slows down and deposits some of its sediment. Annual floods renourished the floodplains on the Nile River, and the sediment enriches the soil on Virginia's floodplains as well. Native Americans located their corn fields on floodplains. After the Europeans arrived, early colonists were also dependent upon annual farm crops, and floodplains were settled before less-productive uplands or hillsides.

Try pouring one glass of water into your mouth carefully - if you pour slowly enough, you can swallow the water without spilling any down your chin. Pour two glasses, slowly, and all can be swallowed without spilling. Now pour two glasses of water at once, or pour from one glass much faster, and a flood will cascade down your shirt.

When the river level starts to drop, perhaps after the surge of water from an intense thunderstorm has passed, the river is described as having "crested."

On August 30, 2004 in Richmond, when Tropical Storm Gaston dropped 12 inches of rain in one afternoon onto downtown Richmond. Shockoe Creek filled up and water overflowed the stream banks, covering the Shockoe Slip restaurant district up to the second story of some buildings. The flooding resembled that of the great Virginia Flood of 1870, when the site of modern Main Street Station was underwater.1

Weather forecasters were surprised that the routine tropical storm traveling north from the Caribbean would stop and create such heavy rains in a small area. Normally, such storms dump just an inch or three on any one place before moving through the area, but Gaston kept on dropping water in the same local area.

Note the fast increase in streamflow of Deep Creek in Amelia County, after Tropical Storm Gaston

Source: USGS - Water Resources of Virginia

Virginia residents are accustomed to about 44 inches of rain per year, and the vegetation reflects it. It takes only a few years for grass, shrubs, vines, and/or trees to create a green cover on Virginia's soils, thanks in large part to the rainfall nurturing new plants. The Atlantic Ocean and Chesapeake Bay moderate the Virginia climate, too. In contrast, the dry California desert still shows the scars of tank tracks from military training exercises during World War II, while the human-caused surface disturbances in Virginia are obscured within months in many cases.

the Feeder Ditch lock in Great Dismal Swamp flooded after Hurricane Mathew in 2016

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Water Management at Great Dismal Swamp (by Frederic C. Wurster, July 27, 2017)

Floods are becoming more common, independent of any change in the climate due to global warming, because development modifies patterns of runoff and the shape of stream channels. When a river channel is narrowed, often in an urban area by filling in the marshes on the shoreline, the volume of the channel is decreased. The inevitable consequence, according to the laws of physics, is that the water must either flow faster (eroding the riverbanks and causing trees/structures to fall into the river) or rise higher (causing floods when waters spill over the riverbanks).

modern infrastructure, such as this Route 29 bridge over Bull Run, is designed to withstand large floods that have a 1% chance of occurring each year ("100 year" floods)

Even if a channel is unchanged by storm-induced erosion, the amount of paving and rooftops increases the probability of floods downstream. When forests and grasslands are replaced by impermeable surfaces, such as parking lots, roads, and buildings, raindrops no longer seep gradually into the ground. Instead, water rapidly flows to the edge of the pavement or roof. There it may have sufficient kinetic energy to erode soil particles and carve gullies, washing silt into streams and converting clear water into muddy brown water.

Total Suspended Solids (TSS) are deposited downstream when water slows down, clogging stream channels. The settling solids coat Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) and block sunlight, killing underwater plants and reducing wildlife habitat. Fish eggs, clams and oysters are suffocated by the silt.

Minimizing that pollution is a major part of the Save the Bay effort. Stream restoration projects excavate legacy sediments that had washed off the landscape in the 1700's and 1800's, as land was cleared initially for agriculture. As much as six feet of sediments accumulated at the mouths of some small Tidewater streams.

Floodwaters surging through narrow channels in those legacy sediments carry Total Suspended Solids downstream. In a normal stream channel not clogged with old dirt, floodwaters rise up out of the channel and spread across the flood plain. As the water spreads out and slows down, sediment is deposited on the flood plain rather than carried towards the Chesapeake Bay. By lowering the flood plain or raising the bed of the stream channel, a stream restoration project intentionally creates a flood in a flood plain.

A one-inch summer thunderstorm would deposit an excess of water that could not be absorbed in the ground. In a small stream valley, the excess runoff would create a small rise in water level at a stream gauge downstream. For example, assume that the excess normally would flow downstream over the course of 24 hours, and cause the water level at the stream gauge to rise to a peak of 6" above average flow four hours later.

Building a shopping center in that small stream valley would not change the total amount of water deposited by the same storm. However, covering the ground with impermeable surface would dramatically speed up the time during which the excess rainfall washed downstream. Instead of taking 24 hours to drain, the excess water would race off the roofs and parking lots into gutters, and be gone soon after the rain stopped (except for a few puddles). The runoff would be faster, the peak water level at the stream gauge would be higher, and more land would be flooded downstream.

Fairfax County encourages drivers to "Don't Drown, Turn Around" rather than require swift water rescue team aid

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), My Time in the Water: Flood Safety Lessons Learned and Flooding on Cinderbed Road

A "flashy" stream has a rapid rise in water level and then a quick drop back to the height of the average flow. Over time, such streams will carve deeper channels, incising themselves into the floodplain and erode streambanks during every storm. Trees and paths along such streambanks are vulnerable. Trees tilting over streams in urban parks are signs of runoff that was accelerated by upstream development.

cars and floods do not mix well

Source: Fairfax County, Flooding in the Chantilly Area

The normal water cycle in Virginia is not always normal. Water in Virginia can cause its own dramatic changes in the surface. The effects of Hurricane Agnes in 1972 are still visible in Nelson County, and the Madison County floods in 1995 substantially reshaped the stream channels in that part of Shenandoah National Park.

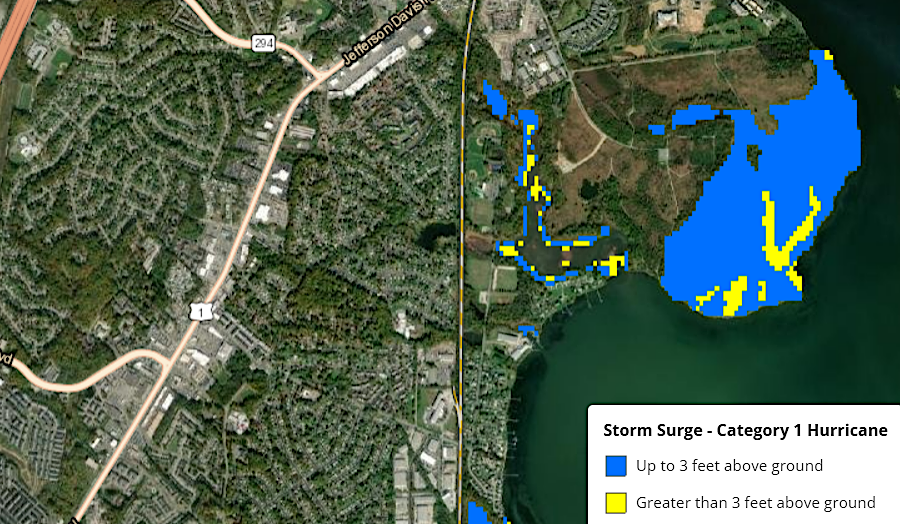

the storm surge from a Class 1 hurricane would flood the eastern half of Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge (Prince William County)

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Coastal County Snapshots

In many areas of the United States, the spring thaw brings on an annual flood as the winter snows melt. When the water flows over the riverbanks, it encounters obstructions - grass, trees, fences, even barns and houses.

low water bridges are designed to be covered occasionally by floodwaters

The obstructions slow the flow of the water, and some of the silt carried in the floodwaters settles out along the edge of the river. The deposited silt fills in the low places near the river edge. In the resulting flat floodplains, the soil is rich in organic material. Floodplains are desirable farmland - the soil is fertile, enriched by nutrients eroded from upstream, while seeds/plants on the flat land are less likely to be washed away by normal rainstorms.

Along the Mississippi River, the deposition of silt along the riverbanks has raised them higher after the floods. These natural levees have been enhanced by man-made walls of earth constructed on either side of the Mississippi, so the annual spring runoff can be directed downstream to the Gulf of Mexico and the farmers can get their equipment into their fields without waiting for the floodwaters to drain away naturally.

In 1993, one of the intermittent changes in the pattern of rainfall created a major flood along the Mississippi River, especially downstream of St. Louis. The Federal government, tired of repetitive payments for "natural" disasters, responded by acquiring farmland that was regularly flooded, and even moving entire towns out of the floodplain.

The concept of "strategic retreat" rather than building higher levees could be applied to the 10,000 miles of coastal shoreline in Virginia. Sea-level rise is a slow-moving flood; rising water levels occur over decades rather than hours, but the impact is comparable to a flood.

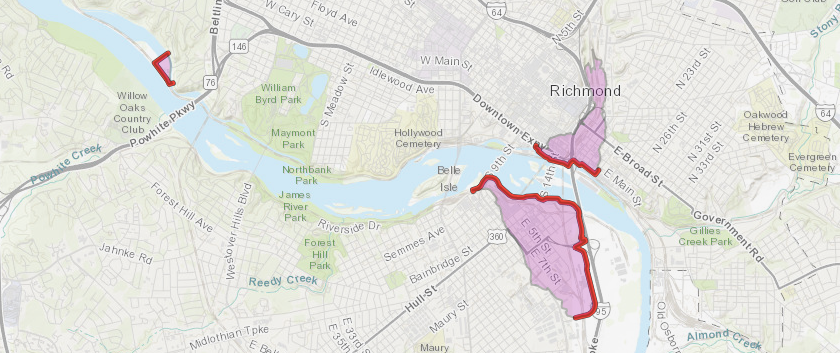

flood walls and levees protect Richmond's drinking water plant, the valley of Shockoe Creek, and a revitalizing area on the south bank of the James River

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, National Levee Database

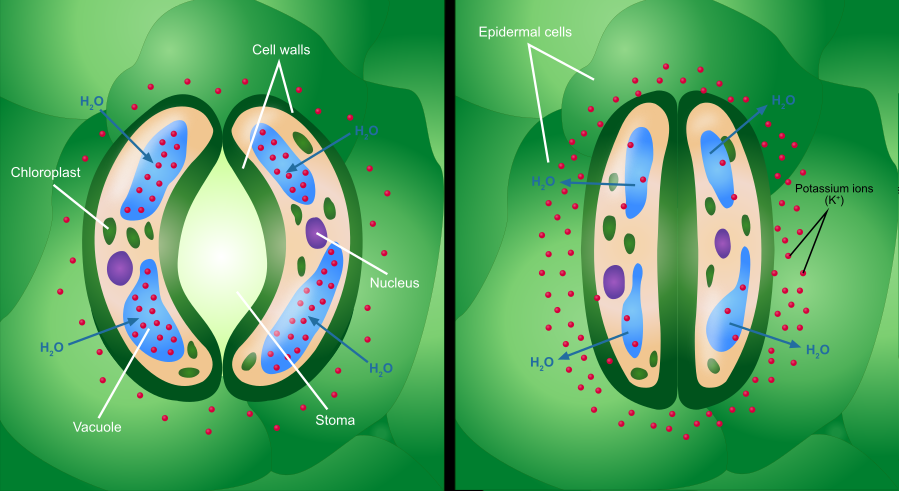

Transpiration of deciduous trees has been reduced by increased carbon dioxide levels, leading to greater flooding. Leaves have openings called "stomata" that allow access to carbon dioxide for photosynthesis of carbohydrates. As the CO2 gas diffuses via the stomata to the plant tissues, moisture which rose up from the roots can escape out of the leaf and evaporate into the atmosphere.

In a forested area, 40% of rainfall returns to the atmosphere through evapotranspiration, without ever flowing into the nearest stream. Even in developed areas with a very high percentage of impervious surfaces, 30% of the rainfall can still go through evapotranspiration, in part because raindrops which land on leaves and branches will evaporate even while infiltration into the soil is blocked.

Leaves on plants sense carbon dioxide levels when they start growing in the Spring, and develop enough "stomates" to absorb the CO2 that will be required to create carbohydrates that season. As a consequence of higher CO2 levels, leaves need fewer openings. As much as 29% less moisture is evaporated back into the atmosphere now compared to the year 1829, so more rainfall is moving to stream channels. That is a major cause for the Mississippi River now rising 2 centimeters (cm) per year, with higher waters creating more flooding.2

as carbon dioxide levels increase, leaves are reducing the number of stomates, which reduces transpiration and increases flooding

Source: Wikipedia, Stoma (by Ali Zifan)

Global warming is leading to more-intense storm events. As one professor noted in 2022, since 1970:3

Great Falls disappeared under a muddy Potomac River, in high water after a May 2014 rainstorm

Homeowners can mitigate the economic impacts of a flood by purchasing insurance. The Federally-sponsored National Flood Insurance Program guides rates for most flood insurance policies.

To reduce the potential impacts of a flood, the Virginia General Assembly directed that 45% of the revenue from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative be directed to the Community Flood Preparedness Fund. Through grants, both inland and coastal localities with floodplain management or resiliency plans can obtain "Flood Fund" grants for flood prevention and protection projects. Priority was given to community-scale hazard mitigation activities that use nature-based solutions to reduce flood risk, and 25% of the funding had to be given for projects in low-income geographic areas.

The legislature created the Resilient Virginia Revolving Loan Fund and provided $25 million in funding in 2022, plus another $100 million in 2023. The Resilient Virginia Revolving Loan Fund assisted individuals and communities to mitigate flood risk, including buyouts in order to move residents out of floodplain hazard areas. It did not prioritize mitigation to minimize future impacts at the community scale, or reliance upon nature-based approaches. Projects in the Virginia Flood Protection Master Plan or the Virginia Coastal Resilience Master Plan were eligible for a loan.4

flood debris on the upstream side of bridge piling at Cartersville, where VA 45 crosses James River

State funding was needed for events which did not qualify for Federal disaster relief. The General Assembly focused on the need after the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) declined to categorize two floods in Buchanan County as national disasters which would have qualified uninsured homeowners to receive $3.5 million in "individual assistance" for private property. In the judgement of the Federal agency, the magnitude and severity of the two floods were not high enough to justify individual assistance from the Federal government.

On August 30, 2021, remnants of Hurricane Ida dropped 4-8 inches of rain during just nine hours on Hurley; the resulting flooding destroyed or damaged over 60 homes and killed one person. On July 12-13, 2022, nearly 100 homes in the Whitewood community were damaged after a similar storm. The Federal Emergency Management Agency limited its assistance to "public assistance" funding to reimburse the local government for recovery expenses and "hazard mitigation" funding for projects to minimize future flooding impacts. The hazard mitigation funding enabled Buchanan County to purchase 34 structures and convert that land into open space, so future flooding would have minimal impact.

flooding in Appalachia washes away building foundations and moves trailer homes

Source: National Archives, Severe Storms, Flooding, and Landslides

After efforts to obtain Federal assistance for uninsured private homeowners failed, in 2023 the General Assembly appropriated $11.4 million for the Hurley Relief Fund Program and $18 million for the Whitewood Relief Fund Program. Grants from the funds were administered by the Department of Housing and Community Development, rather than the Virginia Department of Emergency Management (VDEM) Grant Management and Recovery Division.

The $30 million for the Hurley Relief Fund Program and Whitewood Relief Fund Program came from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). At the same time, Governor Youngkin was trying to withdraw from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, calling it a "hidden tax." The governor called for a direct appropriation in the future for recovery costs which exceeded local resources and which the Federal Emergency Management Agency would not cover.5

The proposed withdrawal from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative generated opposition for several reasons, one of which was the projected impact on funding for flood prevention. Though the General Assembly appropriated $100 million for the Resilient Virginia Revolving Loan Fund in 2023, there was no assurance that future funding would be provided on a regular basis. In contrast, funding from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative that was directed to the Community Flood Preparedness Fund was projected to be nearly $100 million annually.6

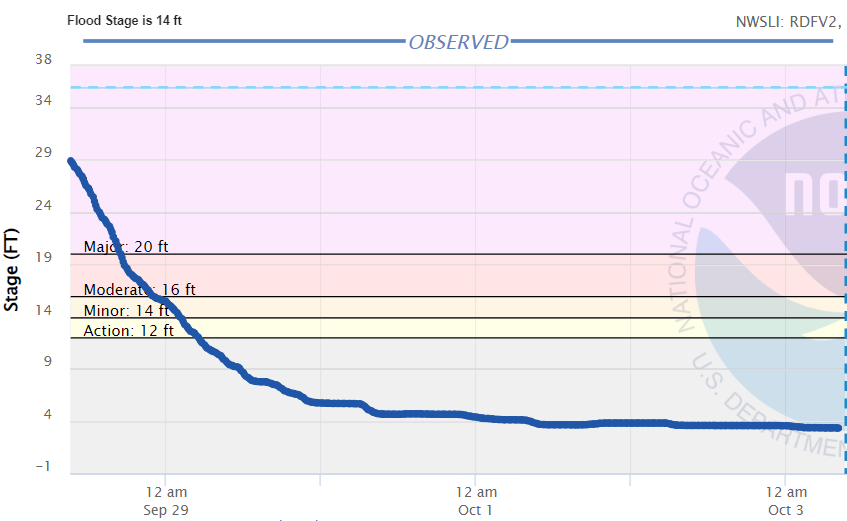

In September 2024, remnants of Hurricane Helene moved inland from the Gulf of Mexico past the Tallahassee area into the mountains of western North Carolina. Almost 30" of rain fell in one day near Asheville, devastating Blue Ridge mountain communities with unexpectedly high floods in a pattern similar to Hurricane Camille in 1969. The New River crested at 31 feet in Radford, where the flood level is 14 feet.

The Virginia Creeper Trail was heavily damaged, with most of the bridges uphill from Damascus washed downstream or totally destroyed. Restoration costs were estimated at $200-300 million, and the US Congress appropriated funds for the Helene-related repairs. US 58 was closed in Washington County from late September 2024 until repairs were completed in late May, 2026.

in 2024, runoff flowing north from remnants of Hurrricane Helene in North Carolina raised the New Rver in Radford far above the 14' flood level

Source: National Weather Prediction Service, New River at Radford (October 3, 2024)

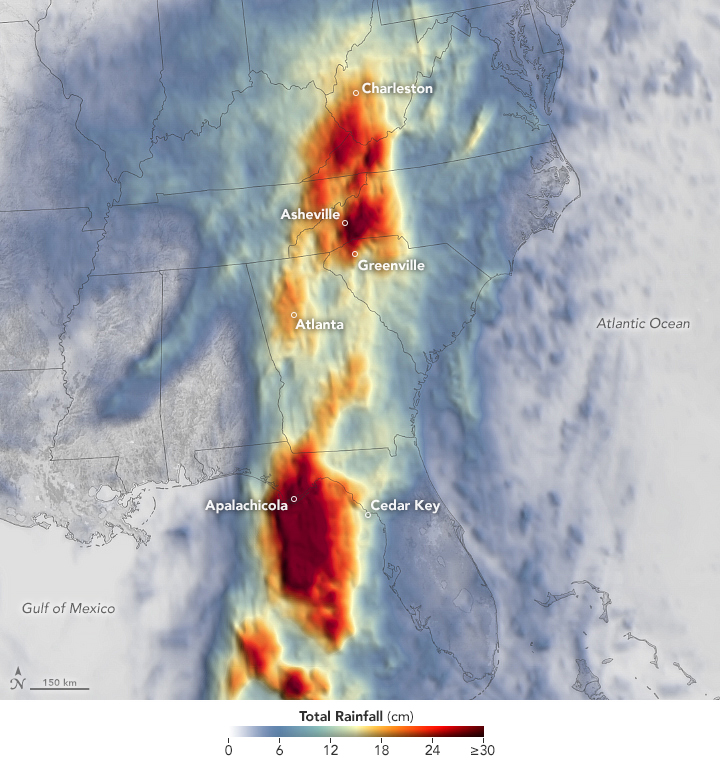

remnants of Hurricane Helene in 2024 triggered catastrophic flooding in the Blue Ridge

Source: NASA Earth Observatory, Devastating Rainfall from Hurricane Helene

Rainfall was intense in part because the ground was warm and there had been earlier storms. The ground was saturated, so runoff was increased. In addition, evaporation in the warm temperatures increased the amount of moisture available to trigger additional rain. Saturated land creates a "brown ocean" effect, adding energy and moisture to storms.7

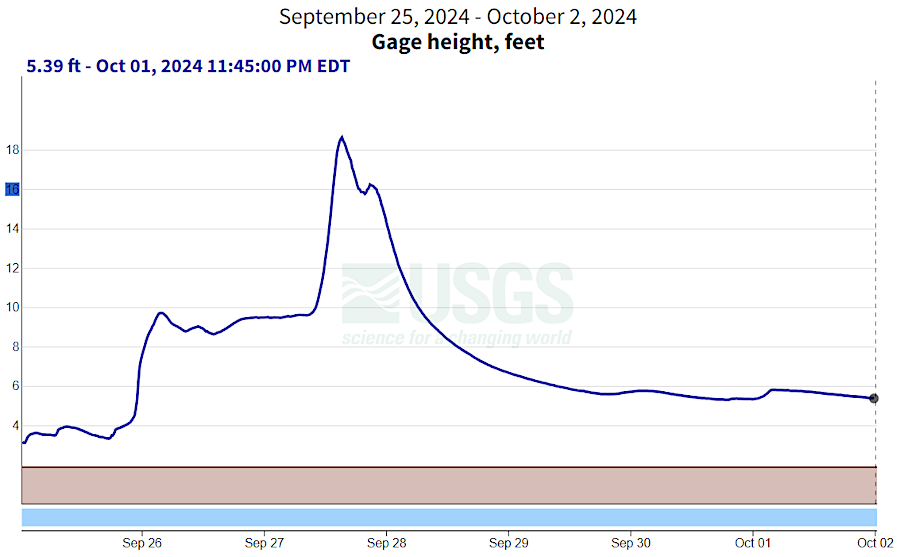

remnants of Hurricane Helene caused short-term flooding on the South Fork of the Holston River in 2024

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Water Watch - S F Holston River Near Damascus, VA - 03473000

height of historic floods at Great Falls Park on the Potomac River

Bull Run at Manassas Battlefield, May 2014