National Flood Insurance Program

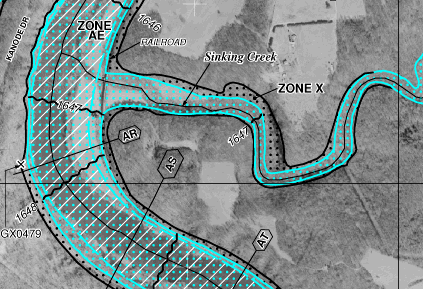

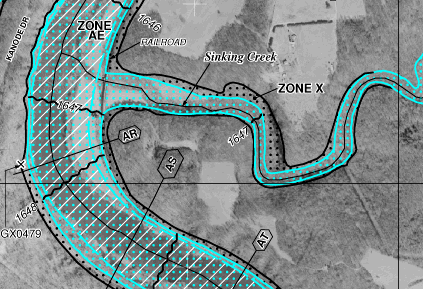

the Flood Insurance Rate Map for confluence of Sinking Creek and New River, at Eggleston in Giles County, shows most of the area with a 1% risk of a flood (Zone X) is also in the floodway (Zone AE)

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Flood Plain Map ID 51071C0240C

Standard homeowners insurance policies do not cover flood risks. Homeowners have to purchase special flood insurance policies if they want to be compensated after a house is destroyed by rising water. Without the special flood insurance policy, a flood could force homeowners without spare money to go live with family or become renters.

The Federal government created the National Flood Insurance Program in 1968 to offer subsidizes so private companies would issue flood insurance policies. The private insurance companies had been unwilling to write flood insurance policies because they could not assess flood risks and calculate the appropriate premiums to charge customers.

Development of detailed data, such as the National Hydrography Dataset from the US Geological Survey, was not available when the National Flood Insurance Program was initiated. Premiums are based on the probability of damages, and the risk of a structure being flooded could not be calculated easily until recent advances in mapping technology.

Congress changed the rules for Federal disaster relief after a flood in 1968, expanding the level of Federal support. The legislators established the National Flood Insurance Program, ensuring funding for future recovery after a disaster but imposing requirements on communities to reduce the potential damage from a flood.

Congress could not regulate directly the future construction in floodplains because the Federal government does not issue building permits. In Virginia, that is the responsibility of local towns, cities, and counties. The US Congress overcame this limitation by linking Federally-subsidized flood insurance to changes in local zoning.

In order for landowners to qualify for the Federally-endorsed flood insurance, a political jurisdiction was required to implement a floodplain management ordinance to reduce future flood risks to new construction. Local floodplain management ordinances must be based on Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) identification of areas with different flood risks. Through that linkage, communities with authority to regulate building or establish construction priorities were required to minimize the potential costs of future disaster relief efforts that would be funded by the Federal government.

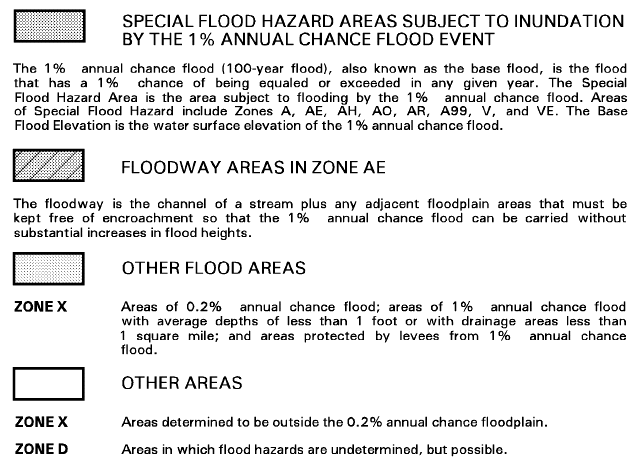

The Federal Emergency Management Agency classifies areas with at least a 1% chance of flooding each year as Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHA's). Special Flood Hazard Areas will be inundated by a "base flood."

They are often described as areas within a 100-year flood plain, but translating the 1% risk to once-in-100-years is not accurate. Each year, there is the same 1% chance of a flood. Within a year, there is the same 1% chance every day. Areas with at least a 1% risk of experiencing a "base flood" have a 26% chance of flooding over the life of a 30-year mortgage.

Before approving a mortgage, Federally regulated or insured lenders require property owners exposed to at least a 1% risk to purchase flood insurance. In such risk areas, such as the Atlantic Ocean coastline exposed to storm surges or mountain valleys where tropical storms can dump inches of rain in just several hours, the monthly cost of such insurance can be a significant factor in determining if potential buyers will qualify for a loan.

Private lenders not insured or regulated by the Federal government may offer mortgages without requiring flood insurance. If buildings are destroyed by a flood and the owner stops paying the mortgage, the lender can repossess property that was identified as collateral for the loan. However, the value of that property after a flood may be less than the loan amount - which is why Federally regulated or insured lenders are mandated to require flood insurance.1

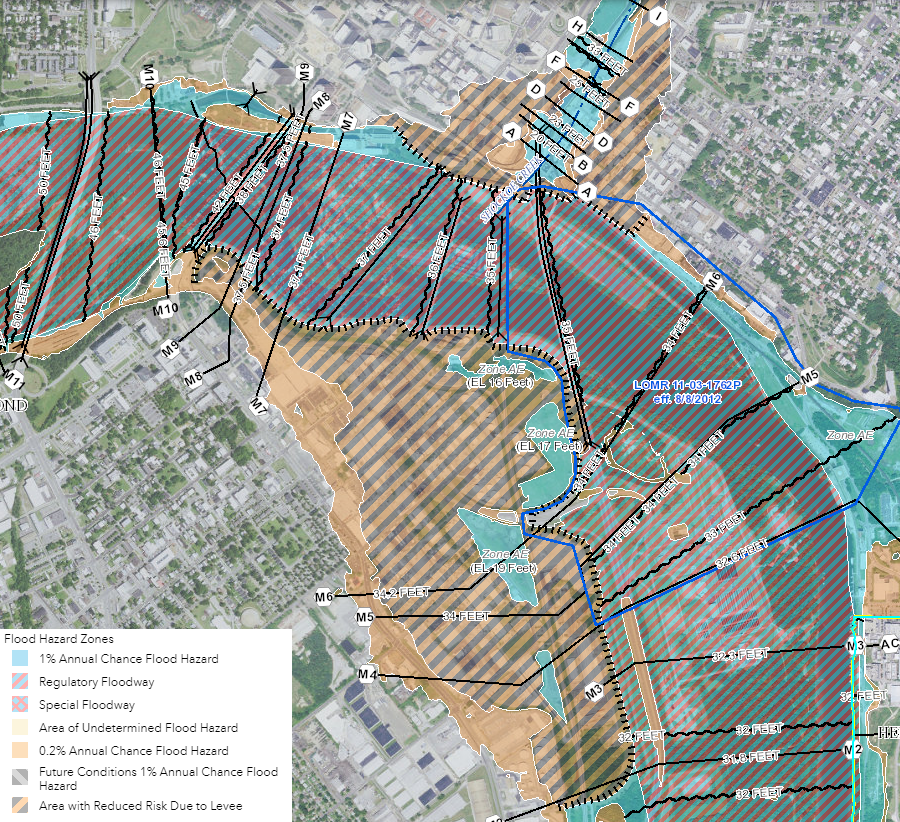

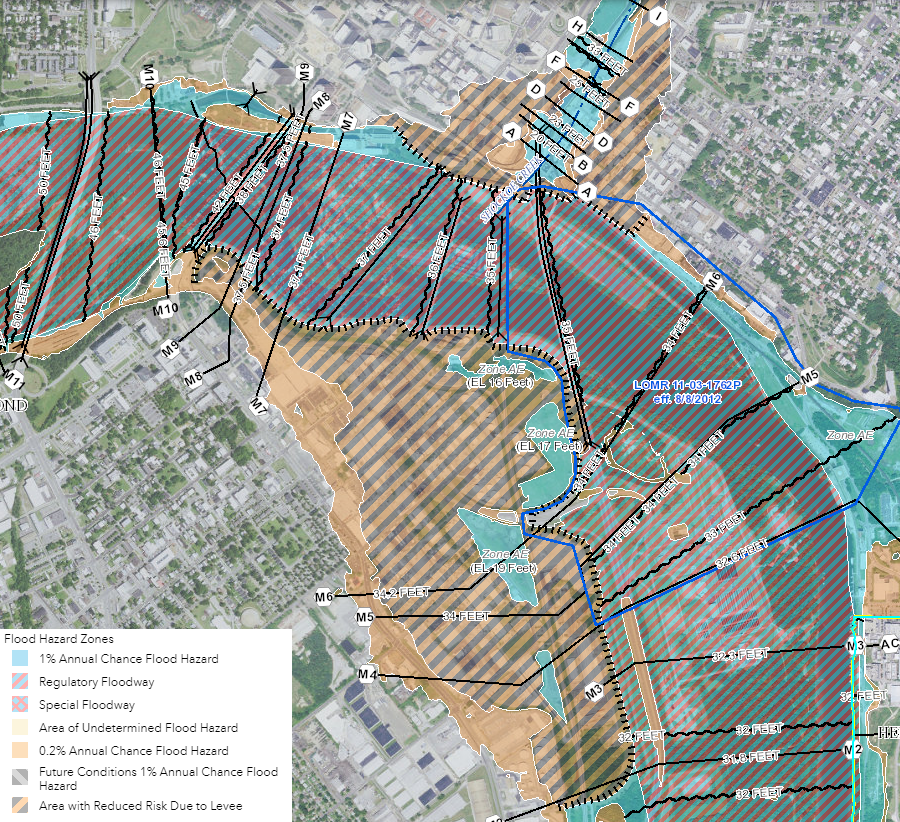

flooding risk in downtown Richmond has been mitigated by construction of flood walls

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), National Flood Hazard Layer (NFHL) Viewer

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) produces Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) so property owners and insurance companies are aware of the flood risk on every parcel within participating communities. The National Flood Hazard Layer (NFHL) is a geospatial database that now covers 90% of the US population.

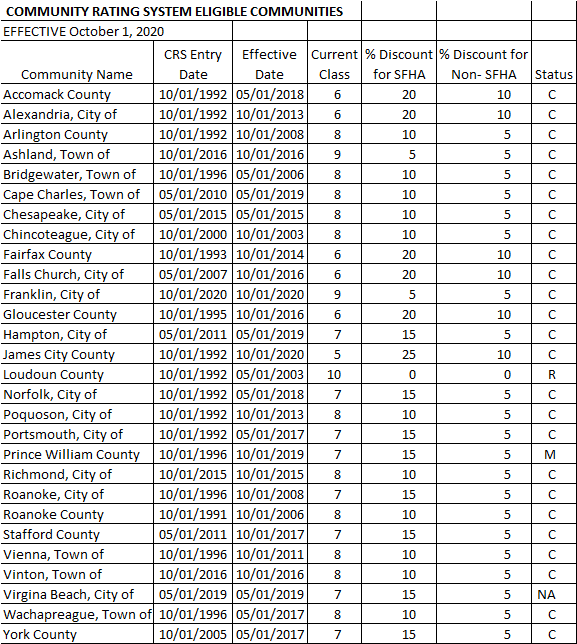

On the flood maps, areas with at least a 1% annual chance of flooding are shaded and identified by codes that start with the letter "A."

Floodways, the channels of streams carrying most floodwaters where development is largely prohibited, are coded AE. Areas between the limits of the 100-year and 500-year floods are shaded and marked with codes "B" or "X." Areas with limited flood risk outside the 500-year flood plain (with less than a 0.2% chance of flooding each year) are not shaded on the map, and coded with a "C" or "X."

Updates to Flood Insurance Rate Maps are transmitted by the Federal Emergency Management Agency to local jurisdictions as Letters of Map Change (LOMC). Homeowners seeking to avoid a requirement to purchase flood insurance can ask for a map review. If warranted, the Federal Emergency Management Agency will respond with a Letter of Map Amendment (LOMA) or Letter of Map Revision Based on Fill (LOMR-F) saying a structure is elevated high enough that it would not be inundated by the base flood.2

Flood Insurance Rate Maps define areas of flooding risk

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Flood Plain Map ID 51059C0260E

Homeowners are not required by law to buy flood insurance. Few lenders will provide a mortgage for a house that is at-risk and uninsured, but homeowners without a mortgage are able to drop insurance or avoid buying it. In Virginia, 69% of the houses located within Special Flood Hazard Areas do not have flood insurance policies.

Politicians recognize that most homeowners are voters in a local jurisdiction, and voters/homeowners want the ability to get a mortgage. The Federal incentive has convinced 21,000 communities to manage development in floodplains more agressively.3

By 2018, FEMA had completed Flood Insurance Rate Maps for 290 Virginia towns, cities, and counties that participated in the National Flood Insurance Program - including 29 considered "Minimally Flood Prone" and 11 "with No Special Flood Hazard."

Within Virginia, FEMA maps identified hazard areas in 18 local jurisdictions that chose not to participate in the National Flood Insurance Program. Within those jurisdictions, zoning ordinances did not meet FEMA requirements.

One of 18 was the City of Galax, which withdrew from the program in 1982. Also included were the Town of Dendron (suspended from the program in 1992) and the County of Louisa (suspended in 2016). As a result, property owners in those 18 jurisdictions did not qualify for subsidized flood insurance.4

Mathews County has stayed within the National Flood Insurance Program, but was at risk of being suspended in 2018 after county officials authorized a building permit for the Islander Restaurant on Gwynn's Island. The restaurant was a local icon that had closed after being damaged by Hurricane Isabel in 2003, and its assessed value had dropped 99% from $300,000 to $3,000.

Repairing the restaurant would require $1 million. Repairs exceeding 50% of its value trigger the requirements of the National Flood Insurance Program to use the Flood Insurance Rate Maps. The lowest occupied floor of the repaired restaurant building would have to be at least four feet higher to get out of the floodplain, substantially increasing the costs to put the building back into use.

Mathews County supervisors initially approved rebuilding the Islander Restaurant at its old height. The owners argued to the supervisors that the value of the commercial business should be based on its 2002 assessment. That 2002 value, before Hurricane Isabel and closure, was much higher. Using the 2002 value would allow much more repair work without crossing the 50% threshold.

Local officials also justified their approval by noting the restaurant would be a contributing structure in the Gwynn's Island Historic District. The district was not established yet, however, and the history of the structure did not provide an automatic exemption to the Federal floodplain ordinance requirements.

A week later, the Mathews County supervisors reversed their vote in order to ensure the county would stay within the National Flood Insurance Program.

The director of the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation had advised that their action would be seen as a violation of the requirements set by the Federal Emergency Management Agency could have led to suspension from the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). If that had occurred, each of the 1,400 property owners in the county with flood insurance would have been required to pay an additional $50 per year. In addition, the state official also highlighted a serious concern for a county exposed annually to hurricanes and major "northeaster" storms:5

- It is also very important that you understand that communities which have been suspended from the NFIP are ineligible for certain kinds of federal disaster aid, grants and loans such as in the event of a hurricane or other disaster

Between 1978-2012, Virginians filed over 40,000 flood insurance claims with the Federal Emergency Management Agency and received nearly $600 million in Federal flood payments. The jurisdictions with the greatest number of claims are all in Hampton Roads - the cities of Norfolk, Hampton, Poquoson, Virginia Beach, and Chesapeake. The only jurisdictions in which Federal flood insurance claims had not been paid were the towns of Clinchport, Lebanon, Iron Gate, Strasburg, and Louisa County.6

Paying for recovery after a disaster involves elected officials as well as staff from the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Virginia Department of Emergency Management. The Government Accountability Office reported in 2010:7

- ...currently nearly one in four policyholders does not pay full-risk rates, and many pay a lower subsidized or "grandfathered" rate. Reducing or eliminating less than full-risk rates would decrease costs to taxpayers but substantially increase costs for many policyholders, some of whom might leave the program, potentially increasing postdisaster federal assistance... Increasing mitigation efforts to reduce the probability and severity of flood damage would also reduce flood claims in the long term but would have significant up-front costs that might require federal assistance.

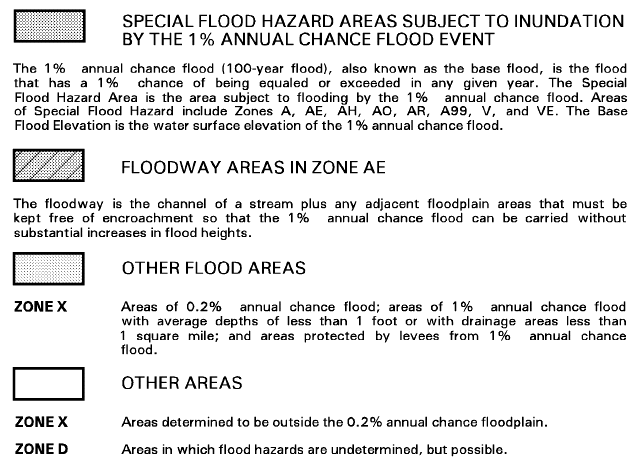

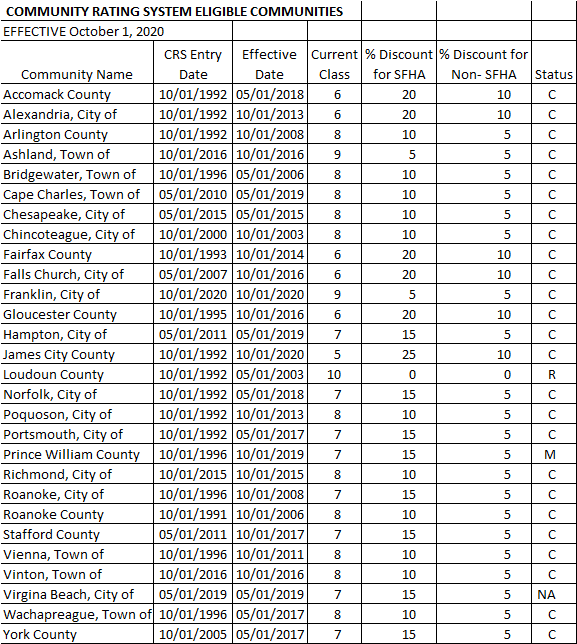

only a small percentage of Virginia jurisdictions manage floodplain development so their residents qualify for a discount on flood insurance

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), National Flood Insurance Program Community Rating System

In 2012, the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act sought to raise flood insurance rates so they were aligned with risk. Ending subsidies and raising rates triggered a political reaction, and the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2014 limited the increases. High costs associated with major hurricanes have left the flood insurance program in deep debt. Since 2012 the US Congress has been unable to reauthorize the program on a long-term basis.

In the absence of adequate appropriations, FEMA borrowed from the US Treasury in order to fund claims made by insured property owners. By 2022, over 10% of the insurance premiums paid by policyholders went to cover interest payments on borrowed money.

Multiple proposals for changes have failed to pass the US Congress, despite bipartisan support. Fundamentally, flood insurance costs exceed the revenue generated by the insurance premiums.8

In October 2021, FEMA implemented a new Risk Rating 2.0 program. As described by the Government Accountability Office (GAO):9

- Risk Rating 2.0 is aligning premiums with risk, but affordability concerns accompany the premium increases. FEMA had been increasing premiums for a number of years prior to implementing Risk Rating 2.0. By December 2022, the median annual premium was $689, but this will need to increase to $1,288 to reach full risk. Under Risk Rating 2.0, about one-third of policyholders are already paying full-risk premiums.

- Many of these policyholders had their premiums reduced upon implementation of Risk Rating 2.0. All others will require higher premiums, including 9 percent who will eventually require increases of more than 300 percent. Further, Gulf Coast states are among those experiencing the largest premium increases. Policies in these states have been among the most underpriced, despite having some of the highest flood risks.

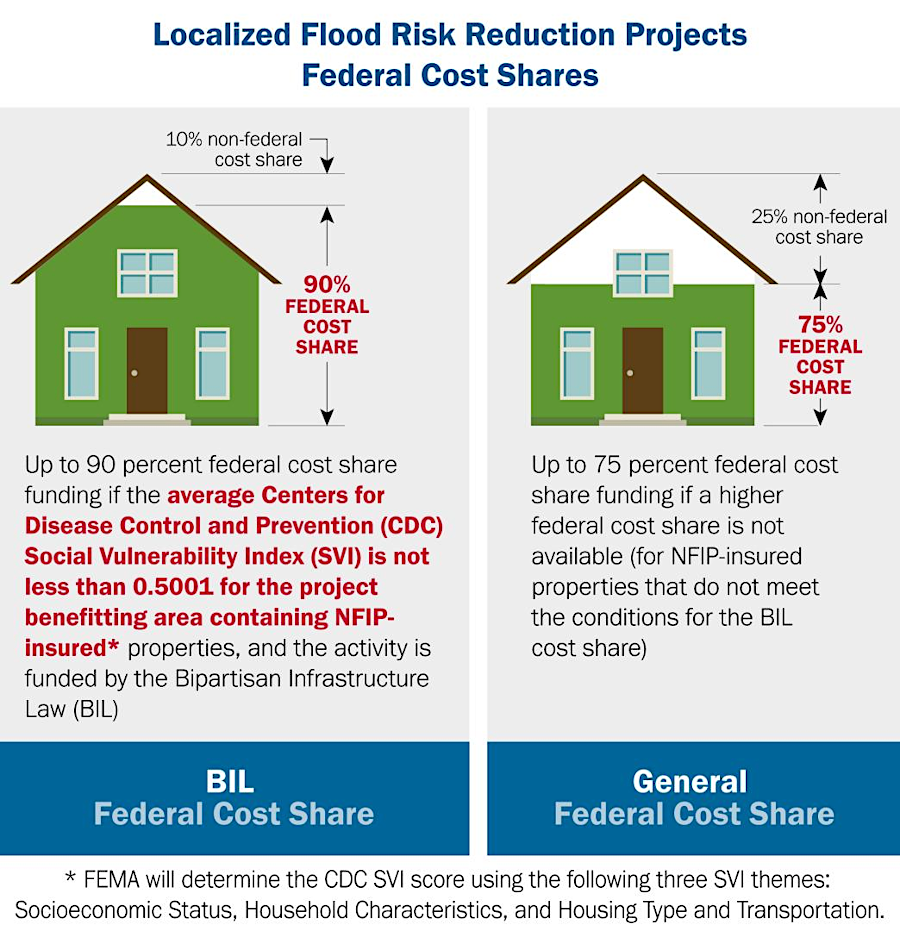

If communities remove existing development from flood-prone areas, risk is reduced. That option becomes politically viable only after a disaster, when property owners might be willing to accept a cash payment and avoid the headache of rebuilding.

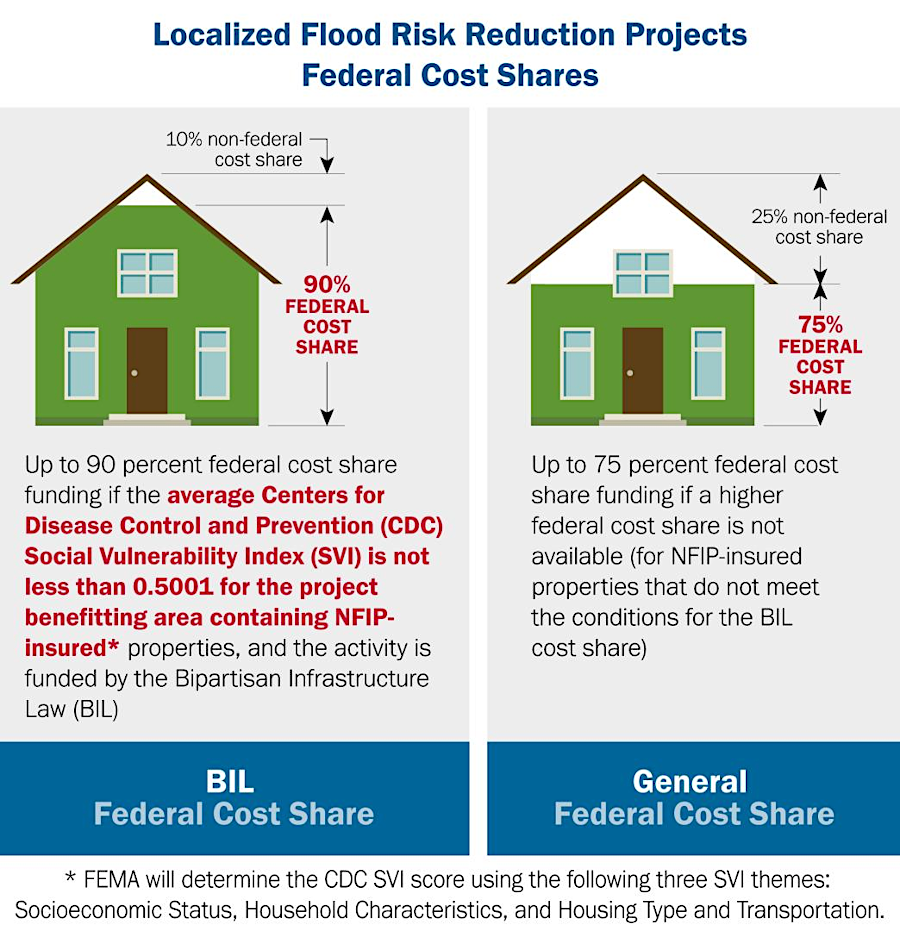

to reduce future costs, FEMA tries to reduce risks of flood events

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), When You Apply for Flood Mitigation Assistance Funds

Private insurance companies are now able to assess flooding risks and set premiums, and have started to sell flood insurance policies in some states such as Florida. A company called CoreLogic can calculate a Flood Risk Score that has more increments than the binary "in flood plain - outside flood plain" choice of the National Flood Insurance Program.

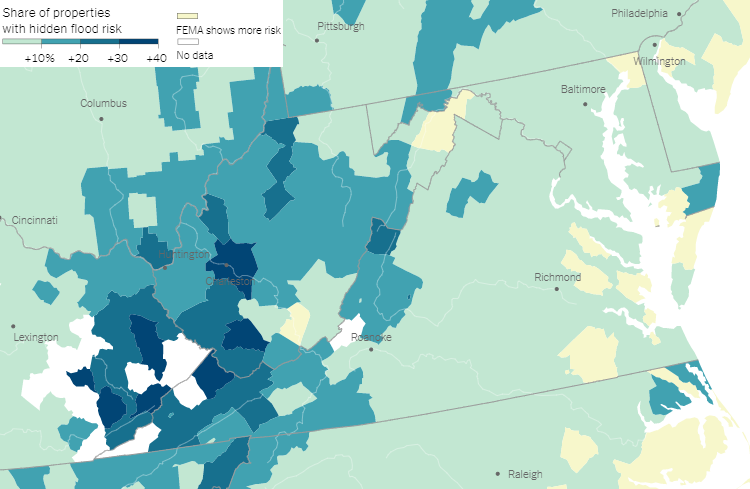

CoreLogic calculates six levels, from Very Low to Extreme risk, for structures in the 100-year and 500-year floodplains. Within Virginia, it claims 17% of the structures at risk are not placed within Special Flood Hazard Areas on Flood Insurance Rate Maps.10

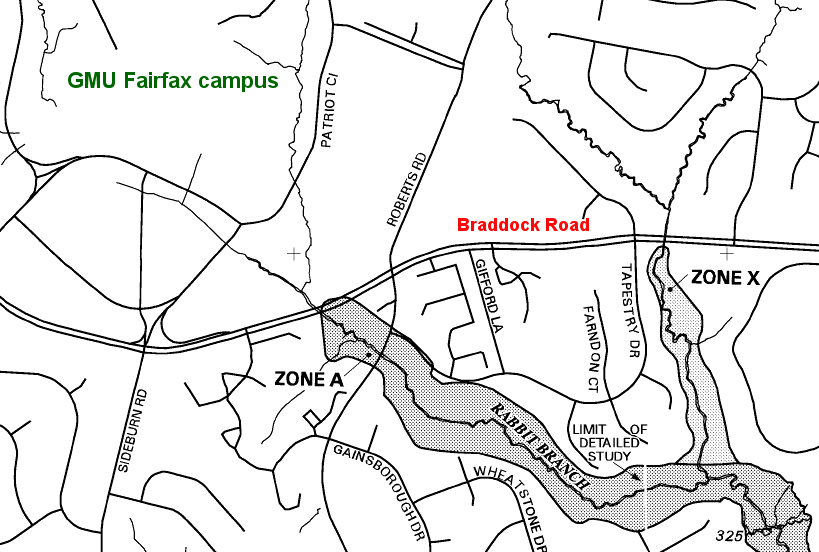

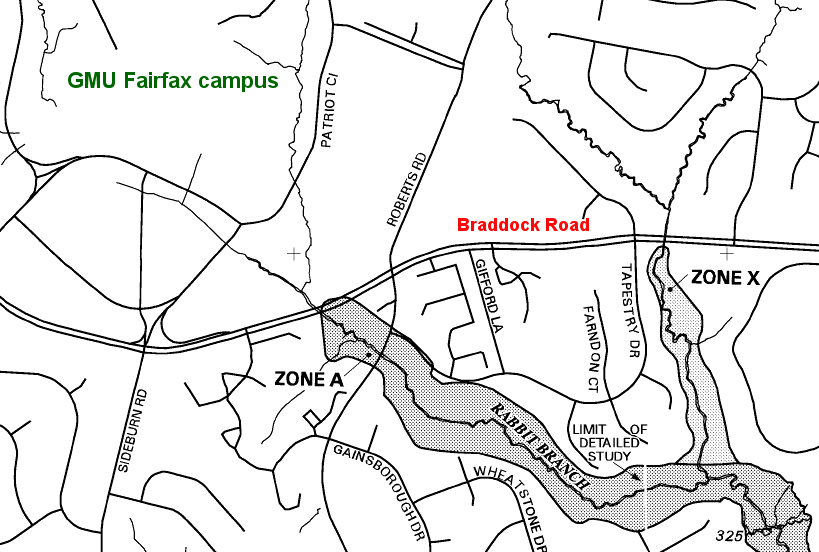

the Fairfax Campus of George Mason University is mapped with code X and is not shaded, so it is outside the 500-year flood plain

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Flood Plain Map ID 51059C0260E

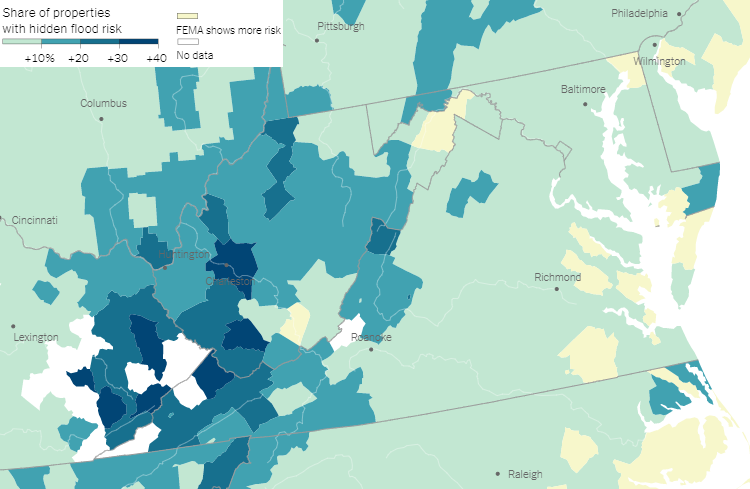

The First Street Foundation reported in 2020 that the flood risk maps from the Federal Emergency Management Agency understated the number of properties at risk in many Virginia jurisdictions.11

the Fairfax Campus of George Mason University is mapped with code X and is not shaded, so it is outside the 500-year flood plain

Source: New York Times, New Data Reveals Hidden Flood Risk Across America (from First Street Foundation)

State funding for flood relief increased starting in 2022, after flooding on August 30, 2021 damaged structures in the community of Hurley in Buchanan County. The Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) provided funding for "public assistance" to cover recovery expenses of local government agencies and projects to prevent future flood damage in Buchanan and Tazewell counties, but rejected "individual assistance" requests. The Federal agency did the same after the July 12-13, 2022 flood damaged the community of Whitewood, also in Buchanan County.

the General Assembly began appropriating funding for flood relief after the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) rejected requests from Hurley in 2021 for individual assistance

Source: Roanoke County Fire & Rescue Department, Facebook post (August 31, 2021)

The General Assembly created the Hurley Flood Relief Fund in response. The state redirected $11 million in Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) funding, intended for low-income energy efficiency projects, to Hurley and $18 million to Wildwood residents.

In anticipation of inadequate Federal funding after Hurricane Helene, the 2025 General Assembly appropriated $100 million. Half was allocated to the Virginia Community Flood Preparedness Fund. Of the $50 million for Hurricane Helene relief, 50% was directed to assist residents who suffered property damage and 50% for improving the ability of structures to withstand future flooding and other hazards.

The 2025 legislature again rejected Governor Youngkin's effort to establish a Disaster Assistance Fund.12

flood walls and levees protect new development planned on the floodplain across the Roanoke River from Carilion Roanoke Memorial Hospital

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, National Levee Database

Links

Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR)

Virginia Department of Emergency Management

Virginia Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD)

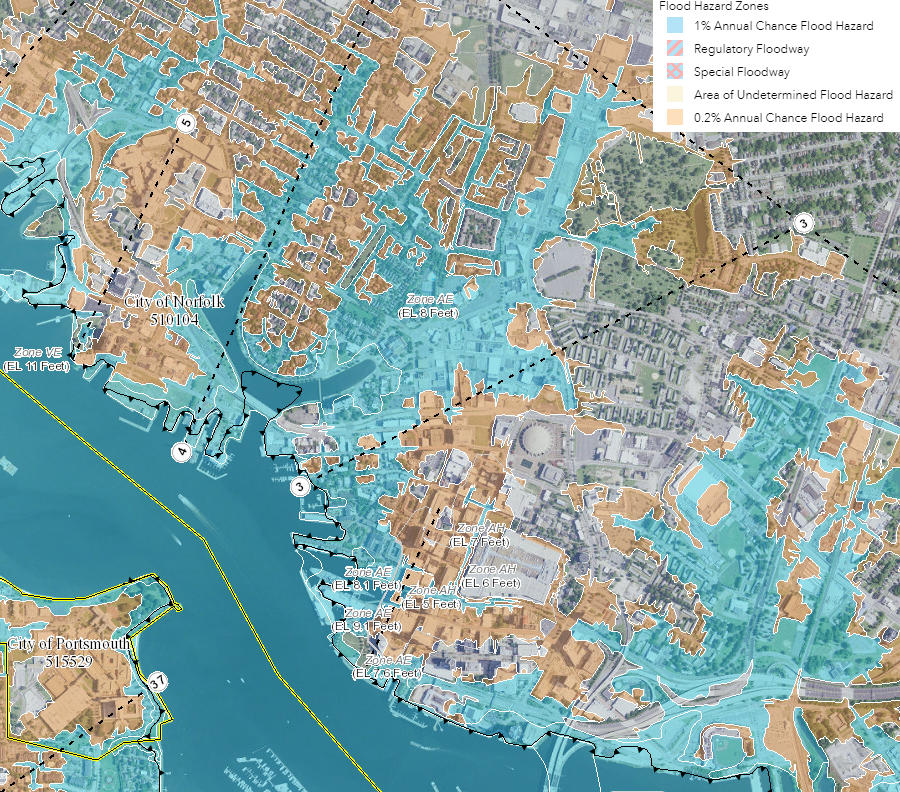

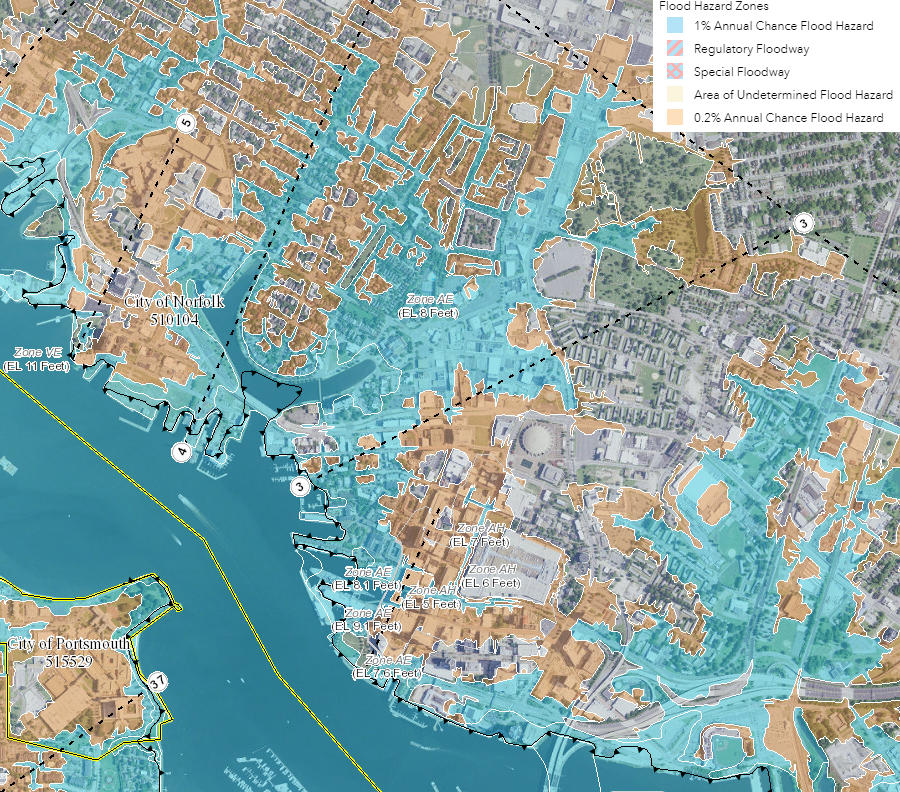

flooding risk in downtown Norfolk

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), National Flood Hazard Layer (NFHL) Viewer

References

1. "Thee 100-Year Flood Myth," Federal Emergency Management Agency, https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/blog/AGENCY-The-100-Year-Flood-Myth.pdf; "Who's required to have flood insurance?," Federal Emergency Management Agency, https://www.floodsmart.gov/am-i-required-have-flood-insurance (last checked October 7, 2024)

2. "FEMA Flood Maps and Zones Explained," Federal Emergency Management Agency, https://www.fema.gov/blog/fema-flood-maps-and-zones-explained; "Change Your Flood Zone Designation," Federal Emergency Management Agency, https://www.fema.gov/flood-maps/change-your-flood-zone; "Flood Data Viewers and Geospatial Data," Federal Emergency Management Agency, https://www.fema.gov/flood-maps/national-flood-hazard-layer (last checked October 7, 2024)

3. "What is the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP)?," Answers to Questions about the National Flood Insurance Program, Federal Emergency Management Agency, http://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/272?id=1404; "Filling Virginia's Flood Insurance Gap," Bacon's Rebellion, November 28, 2018, https://www.baconsrebellion.com/wp/filling-virginias-flood-insurance-gap/ (last checked December 8, 2018)

4. "The National Flood Insurance Program Community Status Book - Virginia," Federal Emergency Management Agency, September 23, 2013, http://www.fema.gov/cis/VA.html (last checked September 22, 2012)

5. "Mathews supervisors reverse decision to assist restaurant," Daily Press, September 9, 2018, http://www.dailypress.com/news/hampton/dp-nws-mathews-county-flood-20180906-story.html; "Board action may have placed residents' flood insurance at risk," Gloucester-Mathews Gazette-Journal, September 5, 2018, https://www.gazettejournal.net/index.php/news/news_article/board_action_may_have_placed_residents_flood_insurance_at_risk; "Board seeks way to help Islander reopen," Gloucester-Mathews Gazette-Journal, February 28, 2018, http://www.gazettejournal.net/index.php/news/news_article/board_seeks_way_to_help_islander_reopen (last checked September 10, 2018)

6. National Flood Insurance Program, Loss Statistics, http://bsa.nfipstat.com/reports/1040.htm (last checked June 20, 2012)

7. "Flood Insurance: Public Policy Goals Provide a Framework for Reform," GAO-11-429T, testimony before the Subcommittee on Insurance, Housing, and Community Opportunity, Committee on Financial Services, House of Representatives by the Government Accountability Office on March 11, 2011, http://www.gao.gov/assets/130/125706.pdf (last checked June 20, 2012)

8. "Laws and Regulations," Federal Emergency Management Agency, https://www.fema.gov/flood-insurance/rules-legislation/laws; "Outlook for flood insurance policy reforms remains cloudy," Civil Engineering, American Society of Civil Engineers, June 23, 2022, https://www.asce.org/publications-and-news/civil-engineering-source/civil-engineering-magazine/article/2022/06/outlook-for-flood-insurance-policy-reforms-remains-cloudy (last checked October 7, 2024)

9. "Flood Insurance: FEMA's New Rate-Setting Methodology Improves Actuarial Soundness but Highlights Need for Broader Program Reform," Government Accountability Office (GAO), GAO-23-105977, July 31, 2023, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105977 (last checked October 7, 2024),

10. "Flood Risk Score," CoreLogic, 2010, https://www.corelogic.com/downloadable-docs/1_flood-risk-score-data-sheet_1302_01final.pdf; "Spotlight on: Flood insurance," Insurance Information Institute, https://www.iii.org/article/spotlight-on-flood-insurance; "Data Brief: CoreLogic Analysis Shows More Than 20 Percent of US Properties at Risk of Flood Are Outside of Designated Special Flood Hazard Areas," CoreLogic, December 1, 2017, https://www.corelogic.com/news/data-brief-corelogic-analysis-shows-more-than-20-percent-of-us-properties-at-risk-of-flood-are-outside-of-designated-special-flo.aspx (last checked December 8, 2018)

11. "New Data Reveals Hidden Flood Risk Across America," New York Times, June 29, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/06/29/climate/hidden-flood-risk-maps.html (last checked August 27, 2020)

12. "After Hurley and Whitewood floods, Virginia considers state relief fund," Virginia Mercury, September 20, 2023, https://virginiamercury.com/2023/09/20/after-hurley-and-whitewood-floods-virginia-considers-state-relief-fund/; "Post-Helene, Virginia granted major disaster declaration, access to federal funding for recovery," Virginia Mercury, October 2, 2024, https://virginiamercury.com/2024/10/02/post-helene-virginia-granted-major-disaster-declaration-access-to-federal-funding-for-recovery/; "5 Takeaways from Virginia’s Conservation Budget," Virginia Conservation Network, June 1, 2022, https://vcnva.org/5-takeaways-from-virginias-conservation-budget/; "Budget deal doubles funding for Helene relief," Cardinal News, February 20, 2025, https://cardinalnews.org/2025/02/20/budget-deal-doubles-funding-for-helene-relief/; "General Assembly Approves Amendments to Biennium Budget," Virginia Association of Counties (VACO), https://www.vaco.org/uncategorized/general-assembly-approves-amendments-to-biennium-budget/ (last checked February 26, 2025)

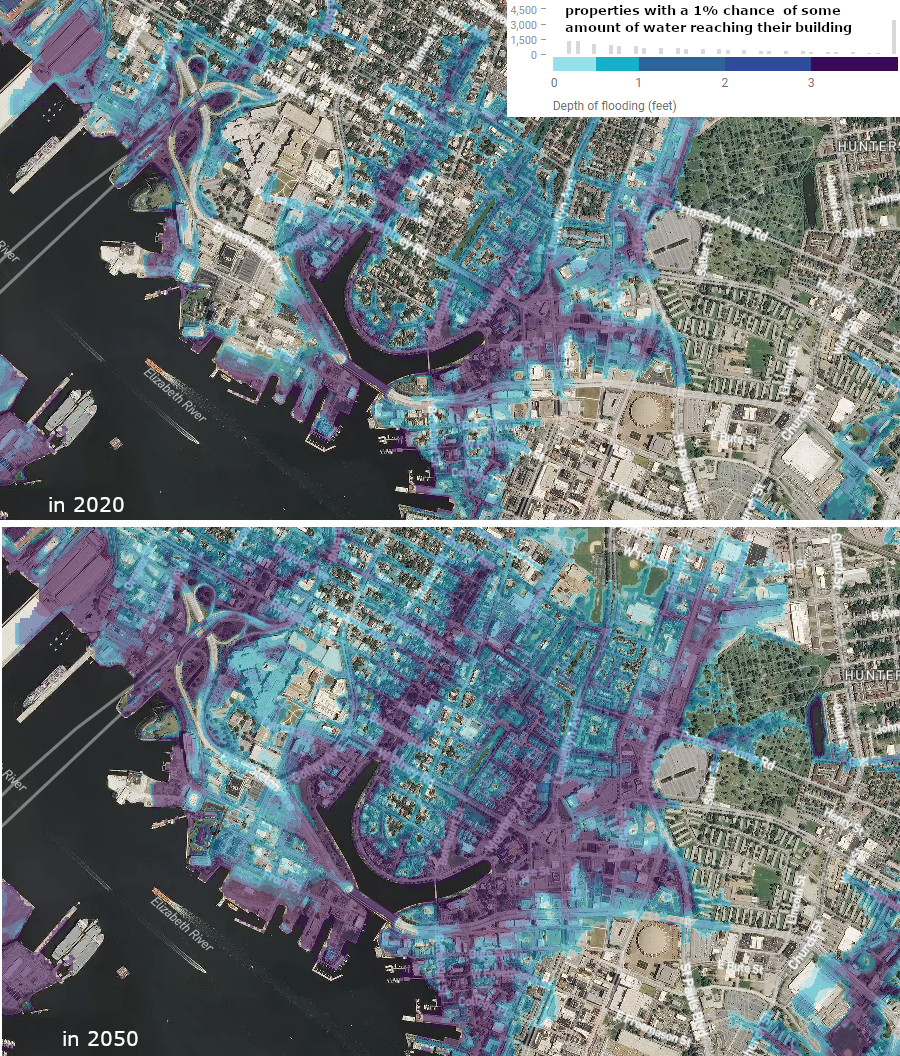

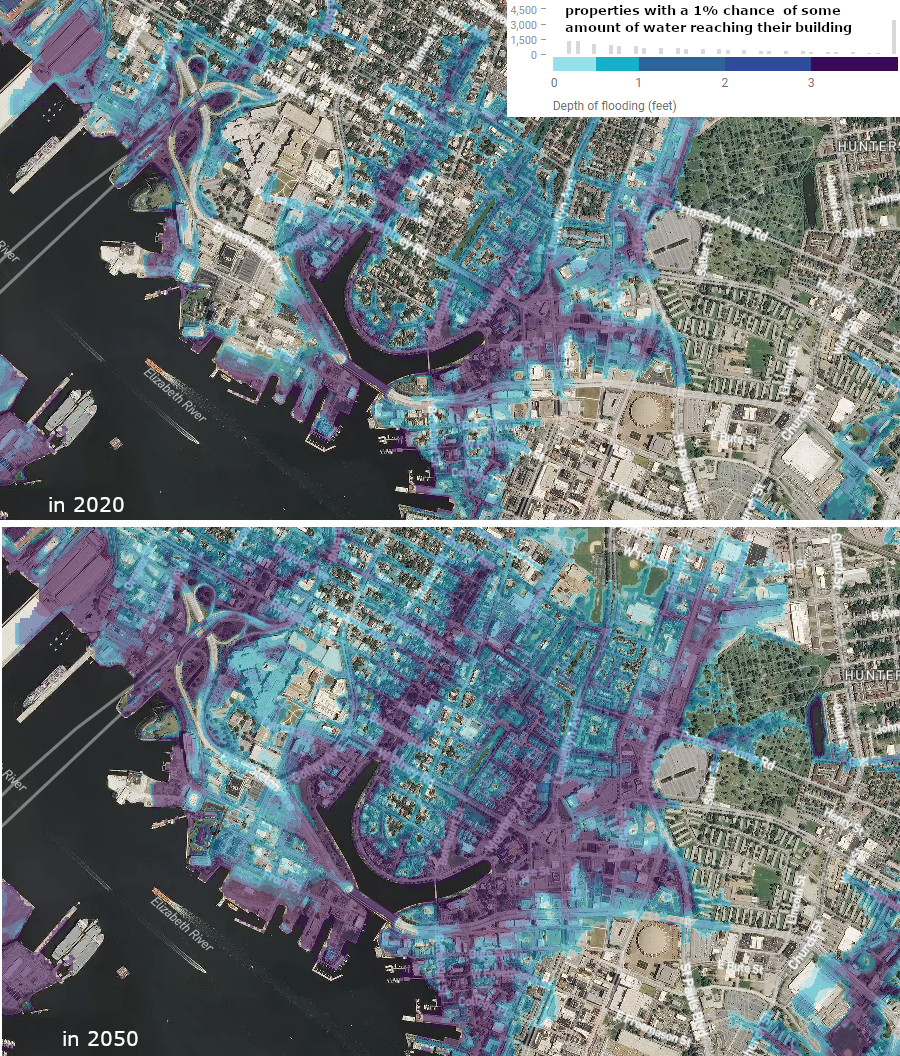

in 30 years, the flood risks will increase in the Ghent neighborhood of Norfolk

Source: Flood Factor, Norfolk, Virginia

Climate

Rivers and Watersheds

Virginia Places