the 4-foot high streambanks of Rocky Branch in Prince William County are the result of legacy sediments deposited over three centuries in the 1700's-1900's

the 4-foot high streambanks of Rocky Branch in Prince William County are the result of legacy sediments deposited over three centuries in the 1700's-1900's

Streams move their channels naturally within their floodplain. The energy of moving water erodes streambanks, changing the location where the stream curves. At times, a shift in the channel may isolate old meanders and create "oxbows," named for their resemblance to the wooden frame used to harness oxen to pull wagons in the colonial era. On the sides of streams, shrubs and trees in the riparian zone are naturally at risk of being undercut as channels migrate.

stream banks are dynamic, with tree roots holding sediment until erosion wins the contest

Patterns of riffles and pools move, as streams lower their base level. West of the Fall Line, streams erode the bedrock at the bottom of their channel. East of the Fall Line, streams in the Coastal PLain carve their channels in unconsolidated sediments.

Minerals in bedrock near the surface gradually dissolve in water. Molecules go into solution and are carried downhill by groundwater and surface streams. Small particles of slow-to-dissolve minerals, especially quartz (SiO2), are carried downhill by surface streams as particles of silt suspended in the moving water. Larger particles move slower as intact grains of sand, bouncing off the stream bottom in a process called "saltation."

As streams near sea level, the stream channels flatten and the speed of the water slows. Lower-energy streams can no longer carry all the suspended particles. They are deposited within the stream channel to form mudbanks and point bars on the sides, and to create a bed of sediment on the bottom.

At times of high water after storms, the volume of flow exceeds the capacity of the channel. Streams typically exceed "bankfull" condition every 1.5 years.1

The extra runoff creates a flood, and water spills out of the stream channel onto the adjacent land. On those floodplains outside the stream channel, water spreads out and slows down, impeded in part by vegetation in the riparian zone. Slower water deposits much of the sediment it was carrying, creating new deposits on the floodplain. Sediment already on the floodplain can be moved around (remobilized) by stormwater, but except in massive storms the net result of a flood will be deposition of more sediment on the floodplain.

Erosion is a natural process, and the flow of sediment from mountains to the Atlantic Ocean has been steady ever since the supercontinent of Pangea split up about 250 million years ago. Natural erosion has created to topography of Virginia, making molehills out of mountains. The sediments that form the Coastal Plain east of I-95 are the eroded remnants of mountains that once towered over 20,000 feet high during the Alleghenian Orogeny, 300 million years ago.

Natural erosion was accelerated by farming practices after colonization. The forests were cut down and replaced with cropland and pasture. Beaver dams disappeared after the animals were trapped out of stream valleys. Livestock trampled streambanks. The result was a massive flow of soil washed off the land into streams.

return of the beavers has resulted in new dams, creating natural stormwater ponds that slow velocity of streams

In the Blue Ridge, mountain soils became thinner as erosion removed soil particles. Productivity declined as organic material washed downstream, but in areas of high topographic relief the eroded material was carried away by fast-flowing water and did not clog the stream channel. In the Piedmont, with less topographic relief and slower-flowing streams, the natural stream channels were buried as soil from both the mountains and nearby cleared lands were deposited on floodplains.

the stream valley of Broad Run in Prince William County at Sudley Manor Road is filled with legacy sediments

Throughout three centuries of unnatural erosion and unnatural deposition, streams continued to flow. They cut deep channels through the sediment as it filled stream channels, creating abnormally-high streambanks. Today it is easy to find stream channels that are six feet deeper than natural, where floodplains were raised up by the accumulation of legacy sediments. Erosion of the sediments can expose buried water and sewer lines, requiring action to protect the underground infrastructure.

a stream restoration project may be triggered by exposure of buried sewer and water lines

Source: Arlington County, Donaldson Run 2006

Modern Piedmont streams are incised deeply into their floodplain, but not because they cut significantly deeper into the bedrock over the last 300 years. Instead, the floodplains grew higher adjacent to the stream edges as excessive sediments were deposited.

4-6 feet of excess soil buried the natural stream channel and floodplain of Broad Run

Storms that had created bankfull conditions prior to colonial land clearing now produce a faster flow of water trapped within the stream channel. The water does not rise higher enough to spread out onto the floodplain every 1.5 years and deposit sediment regularly on the floodplain. A stream entrenched in a deeper channel flows faster, and its greater energy erodes the legacy sediments from the sides. It is inevitable that over thousands of years, the legacy sediments will be washed downstream and the balanced stream channels will be restored naturally by "channel-forming events."2

However, the environmental impacts of the flow of excessive sediment are significant. Many Piedmont streams have become pipes moving dirt down to the Chesapeake Bay, where excessive sediment blocks sunlight from reaching submerged aquatic vegetation and suffocates fish eggs.

Transformation of the landscape has also affected the floodplain vegetation that previously relied upon a shallow water table near streams. Plants that preferred "wet feet" were replaced by species that thrived in drier, deeper soils with greater distance to the water table.

Bull Run etches away at the streambanks between Prince William and Fairfax counties, shifting naturally within its floodplain

In addition to agriculture in the 1700's-1900's, modern development since World War II has altered the speed and quantity of rainwater running off the ground into streams. Faster runoff from impervious surfaces, especially rooftops and pavement in urban/suburban areas, creates higher-velocity flow. Stream channels which had evolved in legacy sediments, based on a surrounding forest, now erode the streambanks faster. The streams may also overflow after receiving excessive amounts of water that runs off impervious surfaces in a shorter period of time. The extra water, with its extra speed, etches the sediments in a floodplain and causes streams to threaten nearby structures.

raindrops that land on parking lots race quickly to streams rather than soak into the soil

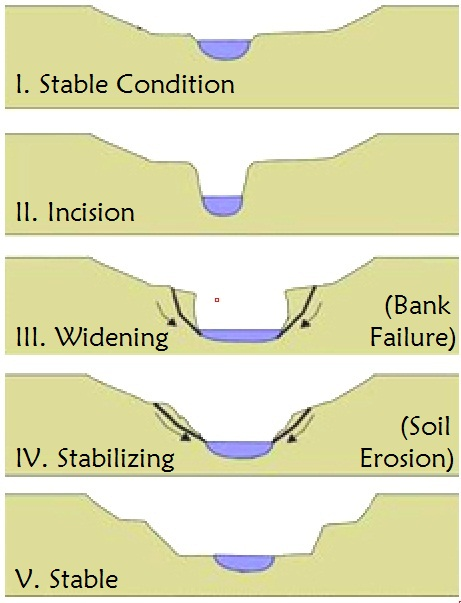

Stream channels will achieve a new balance, over centuries or thousands of years. Erosion will carry away sediment from the unnaturally-high banks, until they reach an angle of repose which reflects the dynamics of flow at that location.

legacy sediments will erode away and stream channels will be balanced again, after many centuries

Source: Fairfax County, Understanding Stream Restoration

Stream restoration projects are designed to reshape the channel to handle the extra flow. A successful restoration typically removes enough legacy sediment to create a channel with a floodplain that will receive sediments every 1.5 years, when streams exceed bankfull condition.

Source: Science, How transforming river banks can clean contaminated waterways

Stream banks where vegetation is removed to reshape the channel must be replanted with native trees large enough to grow a closed canopy, or invasive grasses will dominate the disturbed habitat. Two of the most common invasives are Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum) and small carpet grass, also known as joint-head grass (Arthraxon hispidus). \

small carpet grass/joint-head grass (Arthraxon hispidus) can dominate the streambanks disturbed in a stream restoration project, if not shaded out by a closed tree canopy

as stream banks erode, trees isolated in channels can become barriers to smooth stream flow

Bull Run and its tributaries threaten sewer infrastructure in Prince William County

trunks of riparian trees cut down during a stream restoration project are utilized onsite, not hauled away

Source: Prince William County, Powells Creek Stream Restoration Phase 1 (June 28, 2022)

natives planted at stream restoration projects restore riparian vegetation buffer zones quickly

Source: Prince William County, Powells Creek Stream Restoration Phase 1 (September 20, 2022)

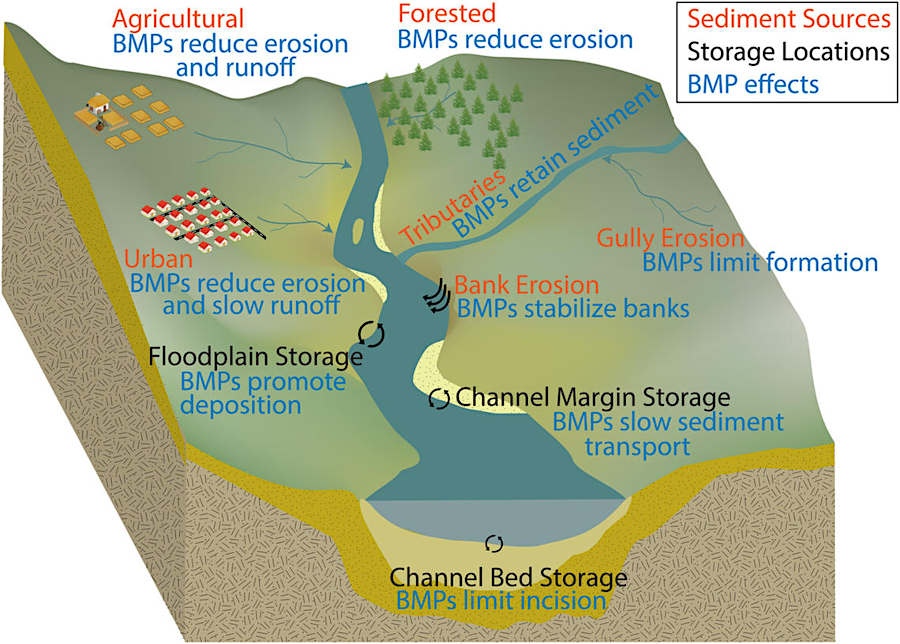

stream restoration is a Best Management Practice (BMP), designed to capture sediment in stream channel margins

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), New Review of Sediment Science Informs Choices of Management Actions in the Chesapeake

legacy sediments on Powell's Creek in Prince William County

Source: Robloxboys, Powells Creek Stream Restoration Project

Source: Robloxboys, Deweys Creek Stream Restoration Project

Source: Prince William County, Stream Restoration - FAQ 1

Source: Prince William County, Stream Restoration - FAQ 2

Source: Prince William County, Stream Restoration - FAQ 3