bulkheads and grass lawns create a sterile edge between land and water

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Center for Coastal Resources Management, Living Shorelines: Photo Gallery

bulkheads and grass lawns create a sterile edge between land and water

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Center for Coastal Resources Management, Living Shorelines: Photo Gallery

The concept of "living shorelines" was developed in response to creating hard physical barriers to block saltwater from flooding shoreline properties and to stop currents from eroding land. Bulkheads were an effective way to protect roads, parking lots, houses and wards from storm surges and erosion, but altered the ecology of the water-land interface.

Source: Longwood University, Living Shorelines

"Hard shorelines" eliminated habitat for juvenile fish and crabs. Walls of wood, concrete and stone blocked the flow of water across mudflats and sandbars, ending the opportunity for underwater grasses and other vegetation to grow.

armored shoreline on Potomac River at Coles Point (Westmoreland County)

Once 10-30% of a shoreline is hardened, the populations of nearby plankton, worms, anchovies, bivalves, crustaceans and other forage species declines. The reduced food affects the populations of species further up the food chain, such as striped bass, summer flounder, Atlantic croaker and white perch.1

leaving gaps between rock barriers permits plankton, crabs and fish to access shoreline habitat

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Center for Coastal Resources Management, Living Shorelines: Photo Gallery

In 2020, the General Assembly prioritized living shorelines as the solution for protection against erosion. The Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) updated its Tidal Wetlands guidelines to establish that "living shorelines" were the first choice when considering ways to reduce shoreline erosion. Rock revetments were the second choice if the best available science did not support creation of a living shoreline, but living shoreline elements should be incorporated wherever possible.2

organic material can be exchanged through porous rock barriers, part of a living shoreline that reduce shoreline erosion

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Center for Coastal Resources Management, Living Shorelines: Photo Gallery

By that time, 18% of the shoreline in Tidewater Virginia was already armored.

To assist in construction of living shorelines, private landowners could obtain funding for 75% of the cost of a living shoreline project from the Virginia Conservation Assistance Program. However, the funding was limited to $15,000 per parcel. The cost of many projects was significantly higher. Local Wetland Boards, which issue permits for altering shorelines, have to consider the public benefits as well as the private costs when defining how much of a living shoreline should be included in a proposed project.3

newly-created living shorelines are planted, and within one growing season provide shelter and habitat

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Center for Coastal Resources Management, Living Shorelines: Photo Gallery

In 2022 Naval Weapons Station Yorktown partnered with the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) and announced plans to build 12 oyster reefs, each 60' long and 12' wide, as living shorelines to protect the facilities' York River shoreline. The US Navy's primary objective was to reduce the threat of erosion to the pier where warships loaded ordnance by dampening wave energy, but valued the habitat improvement benefits as well.4

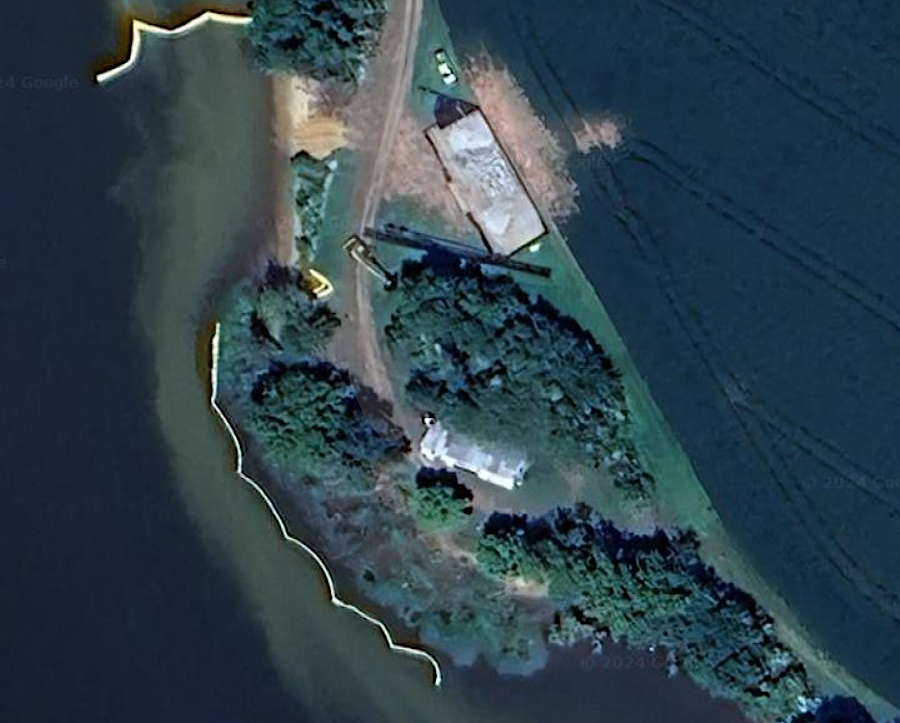

Cheatham Annex at Naval Weapons Station Yorktown protected its pier with a rock revetment

Source: Google Maps

A living shoreline completed in 2024 protected 1,500 feet of shoreline at Berkeley Plantation in Charles City County. That $895,000 project blocked over 100 tons of sediment from eroding into the James River each year. It was the first living shoreline in Virginia to qualify for funding from the Virginia Agricultural Best Management Practice Cost-Share Program, since it protected agricultural land rather than the yard of a riverfront home.5

Berkeley Plantation waterfront before installation of living shoreline

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Berkeley Plantation shoreline after installation of project

Source: Google Maps

Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences (VIMS), Living Shorelines