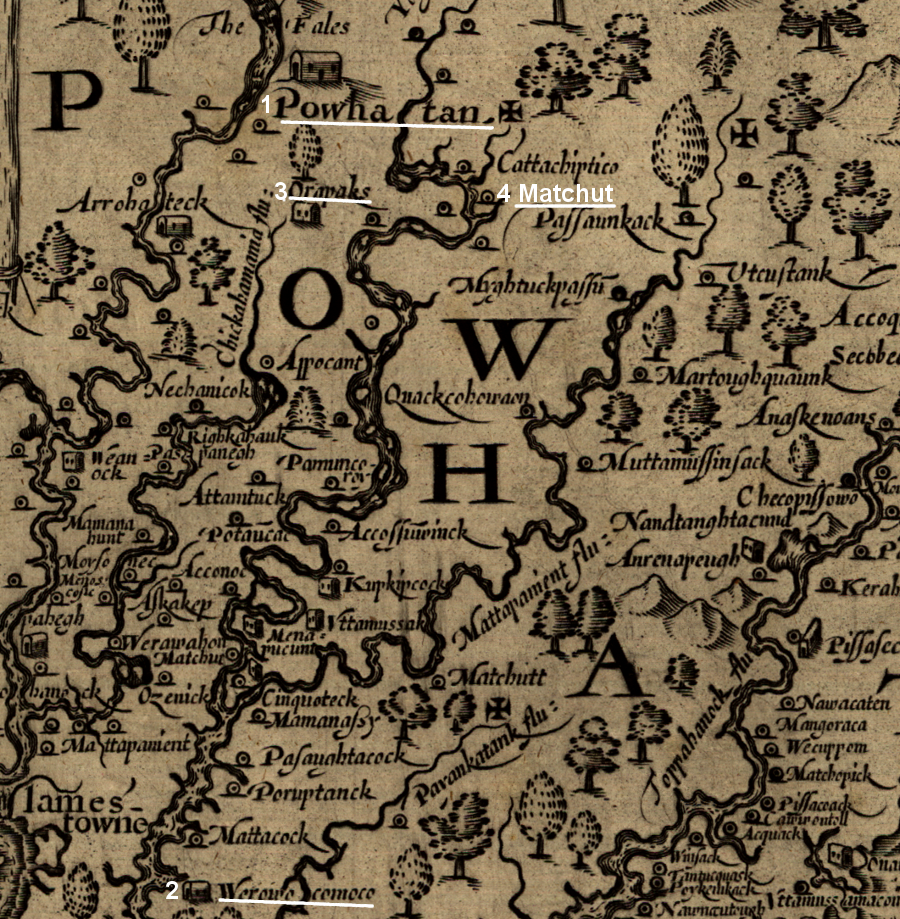

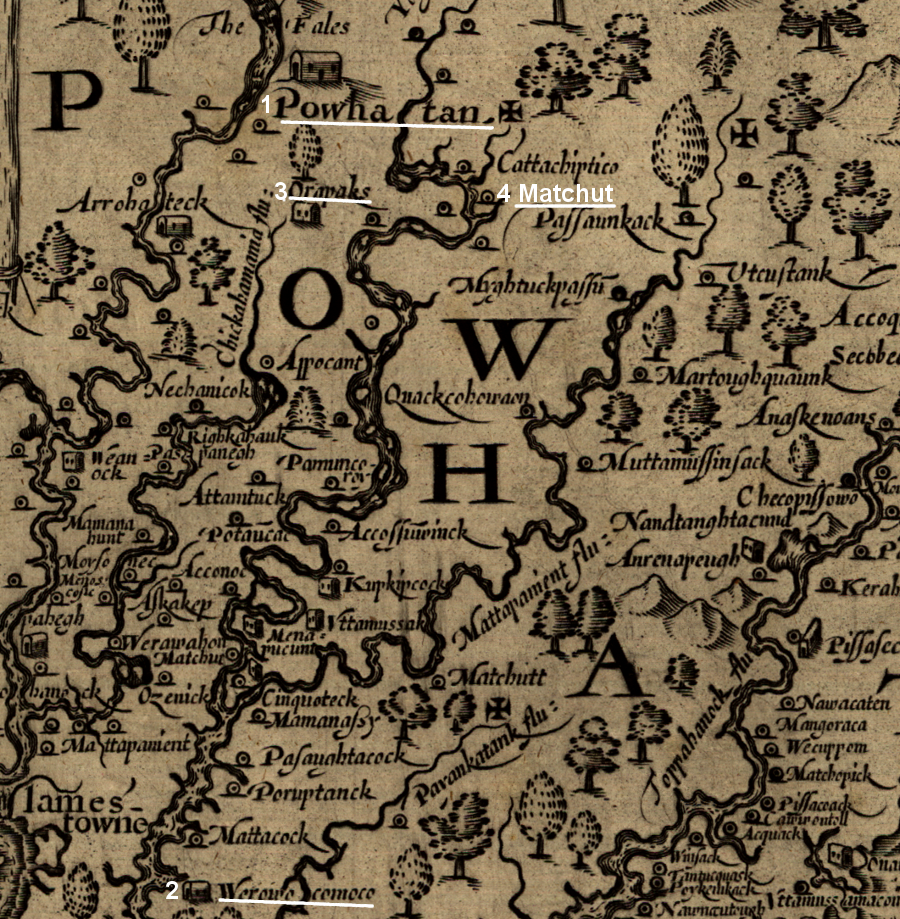

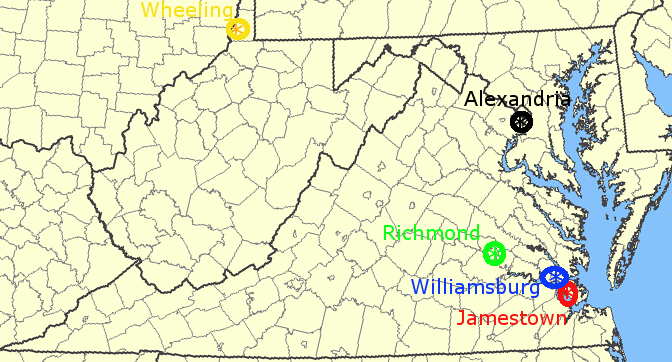

the four capitals of Powhatan, from his original inheritance of "Powhatan" at the Fall Line to Matchut

NOTE: on John Smith's map, north is to the right

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (John Smith, 1624)

the four capitals of Powhatan, from his original inheritance of "Powhatan" at the Fall Line to Matchut

NOTE: on John Smith's map, north is to the right

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (John Smith, 1624)

Richmond has not always been the capital of Virginia, for either the original inhabitants or for the colonists who arrived in 1607.

When the London Company sent three ships to Virginia, the territory in which they landed was ruled by Powhatan. He was the paramount chief over the local tribes in his territory of Tsenacommacah.

Powhatan governed from a seat of power at Werowocomoco, on what we now call the York River.

the specific site of Powhatan's capital at Werowocomoco was identified by archeologists from William and Mary and the Virginia Department of Historic Resources

Source: US Geological Survey, Gressit 7.5x7.5 topographic map

Powhatan had been born in a town further west, and had originally assumed power while living at the base of the waterfalls on Powhatan's River (now called the James River). He extended his control eastward by conquering the Piantatank, Kiskiak, and Chesapeake tribes. He moved to Werowocomoco, which had a long tradition as a special spiritual place, sometime before the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery arrived and disrupted the balance of power.

In 1607, his brother Parahunt was weroance in that town. He ruled as a subordinate of Powhatan, sending tribute of corn and furs to his brother located in his second capital at Werowocomoco.

In 1607, the English colonists established their official seat of government at Jamestown. The English soon discovered that their first capital of Virginia was about 15 miles south of Powhatan's base at Werowocomoco.

the two capitals of Tsenacommacah and Virginia in 1607 (the "Powhatan" at the top of the map is the location of Parahunt's town)

NOTE: on John Smith's map, north is to the right

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (John Smith, 1624)

Powhatan shifted his capital twice before the Second Anglo-Powhatan war started in 1622. In 1609 he migrated westward from Werowocomoco to Orapakes, moving to the swamps at the headwaters of the Chickahominy River. Sometime between 1611-1614, he moved again to the north side of the Pamunkey River, to a location known at Matchut.

Powhatan's authority shifted after 1614 to Opechancanough, who lived nearby at Menmend on the Youghtanund (Pamunkey River). It was the last capital of the paramount chiefdom.

After the 1622 uprising led by Opechancanough, the English pushed the various tribes away from Jamestown. After the 1644 uprising, the Algonquian-speaking natives lost control over Tsenacommacah. Opechancanough was captured and murdered in 1646.

Though the English tried to establish his successors Necotowance, Totopotomoi, and Cockacoeske as ruler of other tribes, they lacked the authority exercised by Powhatan and Opechancanough to direct the actions of other weroances. The towns where they lived were not the "capital" of a paramount chiefdom.

The first English capital was Jamestown, established in 1607.

Despite the ultimate success of English colonization, Jamestown never grew. In 1677, one year after the State House was burned in Bacon's Rebellion, the General Assembly voted to move the capital from Jamestown to Tyndall's Point in Gloucester County. London officials rejected that proposal, and the State House was rebuilt at Jamestown again.

Jamestown served as Virginia's capital for 92 years. The English colonists finally abandoned it after the State House burned again in 1698. Governor Francis Nicholson and the General Assembly shifted the colonial capital to Middle Plantation and renamed it Williamsburg in 1699.1

in 1699, Governor Nicholson and the General Assembly moved the capital from Jamestown (1) to Williamsburg (2), and rejected another proposal for Gloucester (X)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Governor Nicholson had been governor of Maryland, and previously he had moved that colony's capital from St. Mary's City to Annapolis in 1695. He designed Annapolis so streets radiated out from circles that included the Maryland State House and the Anglican church. For Williamsburg, Nicholson chose a rectangular pattern.

He placed the Capitol Building on the opposite end of town from the College of William and Mary. He designed a central road connecting them, and parallel roads on each side were named Francis Street and Nicholson Street.

NOTE: The state capitol is the building that houses the Virginia General Assembly. The capital (spelled with an "a" instead of an "o") is the city in which the General Assembly meets. In Jamestown, the General Assembly met in a church, the governor's house, and the purpose-built structures known as the State House. The first building defined as a government "capitol" was constructed in Williamsburg.

The new name for the capital, replacing "Middle Plantation," honored King William III. The main road was named Duke of Gloucester Street after the son of Anne, the sister of deceased Queen Mary and the successor to the throne once King William III died. Her young son died in 1700, soon after Nicholson's design was completed. The main road in colonial Williamsburg ended up honoring a child instead of a king, since George I replaced Queen Anne.2

Governor Francis Nicholson named the main street in Williamsburg after the heir to the throne, but his name was also placed on the map

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Williamsburg was located in the middle of the peninsula separating the James and York rivers, so it was equally inconvenient for members of the General Assembly who lived in either watershed. The port was at Yorktown, and the distance between the two led to another push in 1738 to move the capital.

The timing for the 1738 effort was related to the death of the Speaker of the House of Burgesses, John Randolph, who had lived in Williamsburg. He was replaced by John Robinson, who lived in King and Queen County within the York River watershed.

The 1738 proposal to move the capital to "a more convenient place" was endorsed by members of the House of Burgesses who supported a new location on the James River. Other members advocated for a new location on the York River or one of its tributaries.

Legislators who wanted to keep the capital at Williamsburg opposed any location further upstream in either the James River or the York River watersheds. They allied in separate votes with the separate James River and York River factions, and managed to kill all proposals to move from Williamsburg.

The Capitol, the building in Williamsburg that housed the General Assembly and the General Court, burned on January 30, 1747. Governor Gooch called a session of the General Assembly to vote for special funding to rebuild, but the House of Burgesses made clear that it wanted to locate the capital at a port on a navigable river. The burgesses voted to "lay the Foundation of a new City... in a Place commodiously situated for Navigation." They discussed two sites on the Pamunkey River, which is a tributary of the York River. The sites were accessible by river, and on the route between Fredericksburg and Williamsburg.

Colonial Williamsburg reconstructed a copy of the first Capitol which burned in 1747, because it had better evidence of that structure's appearance

After considering Newcastle in Hanover County, the House of Burgesses voted 43-33 to build at a different site in New Kent County. The Governor's Council blocked the move, and in reaction the House of Burgesses refused to approve funding to rebuild in Jamestown. After further discussion of sites somewhere on the Pamunkey River or on the James River between the Appomattox River and the Fall Line, the 1747 session ended with no decision.

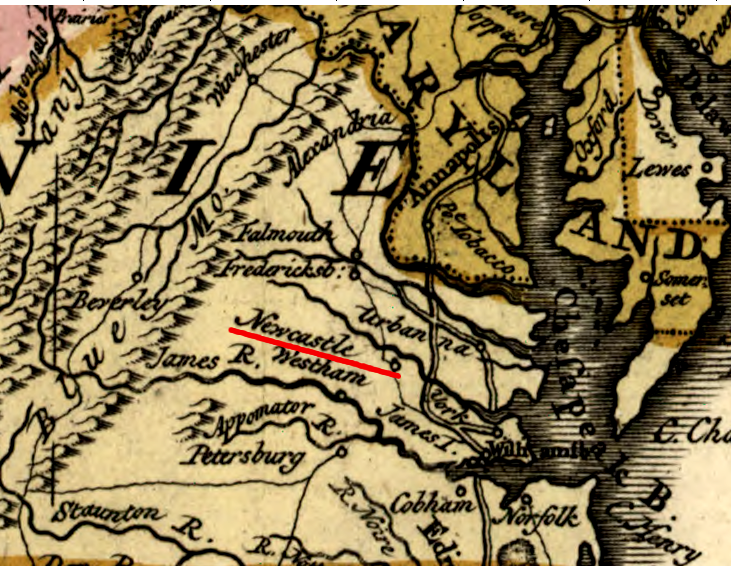

Newcastle was worth placing on the map in 1763, while Richmond was omitted

Source: Library of Congress, A new map of the British Dominions in North America; with the limits of the governments annexed thereto by the late Treaty of Peace, and settled by Proclamation, October 7th 1763 (by Thomas Kitchin, 1763)

Newcastle was still a significant place in 1802

Source: Library of Congress, A map exhibiting all the new discoveries in the interior parts of North America (by Aaron Arrowsmith, 1802)

Governor Gooch then received direction from officials in London to rebuild at Williamsburg. He called another meeting of the General Assembly in 1748. It debated the advantages of moving to Newcastle in Hanover County or Cumberland Town in New Kent County, but House of Burgesses finally approved rebuilding the Capitol in Williamsburg by a 40-38 vote.

A year later the issue popped up again. The House of Burgesses voted to move to Newcastle, claiming the morality of students at William and Mary was being lowered by the crowds who attended sessions of the General Assembly and General Court. The 1749 attempt to reconsider the choice of Williamsburg was blocked by a 4-3 vote in the Council, reflecting the fact that four Council members lived in the Williamsburg area.

In 1752, as the new Capitol was being built, the House of Burgesses voted yet once again to move the colonial capital to Newcastle. Once again, the Governor's Council vetoed the move.

In 1761, another attempt to move was defeated by just one vote in the House of Burgesses. A new attempt in 1766 was discussed, but never came to a formal vote.

In 1770 the General Assembly moved the customshouse for the District of the Upper James River from Jamestown to Bermuda Hundred. That was a sign of support for moving the capital further up the James River, but London officials blocked the move. When the House of Burgesses did vote in 1772 to move by 48-32, once again the Council blocked action.

Advocates of staying in Williamsburg recognized that the inland location was a problem. In 1772 they got the General Assembly to authorize construction of a canal linking Williamsburg to both the James and York rivers. Little construction was completed before the conflicts between colonists and royal officials erupted into the American Revolution.

In 1776, the rebellious Virginians declared independence, breaking with authority in London. That changed the status of Williamsburg into the capital of an independent "Commonwealth," an independent state rather than a colony.

During the first years of the American Revolution, Williamsburg had remained the capital of an independent state that was loosely allied with 12 other independent states. It was still the capital in 1778, when the General Assembly ratified the Articles of Confederation and Virginia committed to surrendering some of its sovereign status to create a national government.

In 1780 the Virginians moved their state capital from Williamsburg. According to traditional political lore, Thomas Jefferson left a blank spot in the bill that he introduced, allowing the legislators to determine the location of the new capital. Reportedly the General Assembly considered Newcastle on the Pamunkey River, not far downstream from Powhatan's last capital at Matchut, before choosing Richmond in a close vote.3

25 years before the capital was moved from Williamsburg, Newcastle - but not Richmond - was important enough to show on a map

Source: Library of Congress, Carte des possessions angloises & francoises du continent de l'Amerique septentrionale. Kaart van de Engelsche en Fransche bezittingen in het vaste land van Noord America (1755)

The General Assembly chose to move further inland from Williamsburg, but stay on a deepwater river. The new location was the small community of Richmond. It was chosen in hopes that the new center of the revolutionary state government would be less vulnerable to British attack. Thomas Jefferson, governor at the time, later wrote:4

Moving inland was not sufficient to protect the state capital. To defend Richmond, the Virginians needed more than just distance.

The Virginia militia was weak and the major units of the Continental Army were stationed outside the state. Governor Thomas Jefferson did not have enough military forces to protect the new capital, and in 1781 the British successfully marched into Richmond twice. They found few public buildings to destroy since the state government was still renting space for offices and General Assembly meetings, so it could be argued that the tactic of moving from Williamsburg was partially successful.

Governor Jefferson and officials in the state government fled Richmond in May, 1781. The General Assembly adjourned its session to meet again in Charlottesville on May 28, 1781.

One of its first acts of business would be to elect a new governor, since Jefferson's term ended on June 2. They had not done so when Jack Jouett completed a dramatic ride from Louisa through the night of June 3 to warn that "the British were coming." The General Assembly held a quick session on the morning of June 4 at the Swan Tavern in Charlottesville, where many members had spent the night, and took appropriate action:5

Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton led his cavalry into the city on June 4, 1781. Jefferson fled south to his Poplar Forest plantation near Lynchburg, while and most of the other Virginia officials crossed the Blue Ridge to safety in Staunton. Approximately five unfortunate legislators, including Daniel Boone, were captured.

The General Assembly met at Trinity Church in Staunton on June 7-23, 1781. On June 11, while meeting in Staunton, the legislators elected Thomas Nelson to replace Jefferson as governor.

The official meetings of the General Assembly in Charlottesville and Staunton may qualify them as "temporary" capitals of Virginia. Once the threat from the British was removed, the state officials resumed their work in Richmond.6

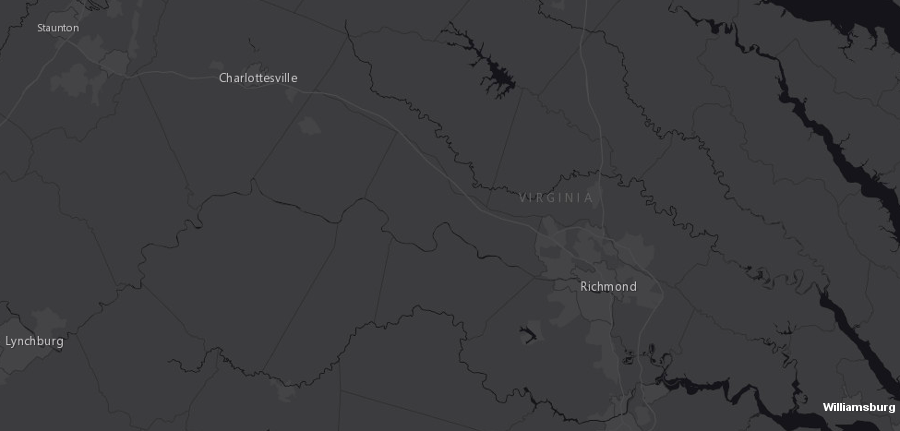

in 1780-81, the General Assembly convened in Williamsburg, Richmond, Charlottesville, and Staunton

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Richmond had become the capital of a subordinate state government within a national union before the General Assembly decamped to Charlottesville. Maryland ratified the Articles of Confederation on January 30, 1781, the last of the states to join the new United States of America. On June 26, 1788, Virginia ratified the new US Constitution. Those documents created and then strengthened the power of the national government, but union with other states did not alter Richmond's status as Virginia's state capital.

Richmond's status did change in 1861. Virginia seceded from the United States of America and joined the Confederate States of America. The Confederate capital moved in June, 1861, from Montgomery, Alabama to Richmond. According to the Confederate perspective, Richmond became the capital of a new (but smaller) national government.

The Virginia governor and General Assembly still remained in Richmond. The Confederate and state legislatures orchestrated their meetings in order to share the same capitol building. Richmond was simultaneously the home of the Confederate government, the state government, and the city's own municipal government.

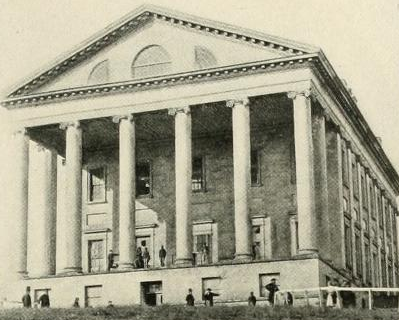

the Confederate Congress met in the Virginia State Capitol building between 1861-1865

Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, The Goal - The Confederate Capitol (p.282)

Viewed from a Confederate perspective, Richmond remained the state capital during almost all of the 1861-65 Civil War. On the night of April 2, 1865, that status changed when Jefferson Davis and the Confederate government abandoned the city. The Confederate officials used a train on the Richmond and Danville Railroad to flee to Danville, which became the last capital of the Confederate States of America.

Gov. William "Extra Billy" Smith and the General Assembly also left Richmond before the Union Army occupied it on April 3. The Virginia state officials took a canal boat and fled upriver to Lynchburg, via the James River and Kanawha Canal. They arrived three days later. Lynchburg became the de facto capital of Virginia from April 6-10, 1865.

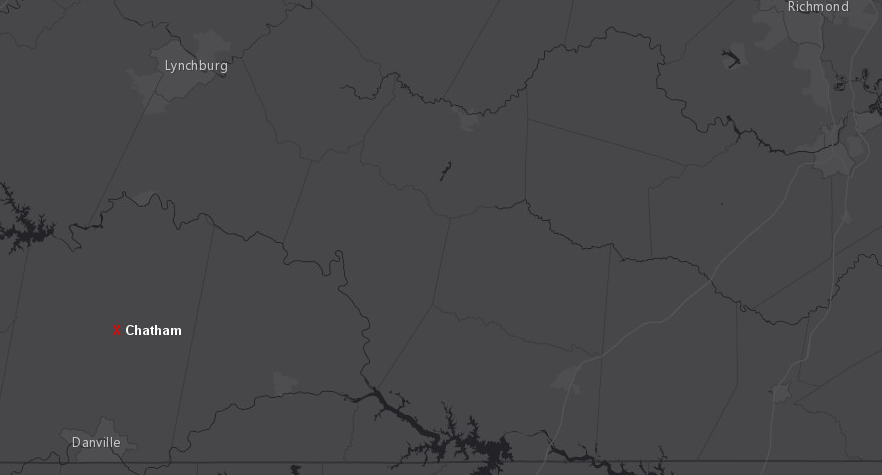

After Governor William "Extra Billy" Smith learned of Lee's surrender at Appomattox on April 9, he rode to Danville to meet with Jefferson Davis at the Sutherlin Mansion. The Confederate officials were fleeing further south to Greensboro, and Governor Smith went west to Chatham (known then as Competition) in Pittsylvania County before acknowldging that his authority had evaporated. Chatham can claim to have been "Virginia's Capital for A Day."7

after the Confederates abandoned Richmond on April 2, 1861, Governor Governor William "Extra Billy" Smith fled to Lynchburg, Danville, and Chatham

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

From a Union perspective, Virginia's state capital moved in 1861, 1863, and 1865 and the Restored Government of Virginia was the official state government of Virginia between 1861-65. After Virginia voted to secede on May 24, 1861, supporters of remaining in the Union organized a convention at Wheeling, Virginia on June 11, 1861. That led to creation of the Restored Government of Virginia, which categorized Wheeling to be the state capital.

On June 20, 1863, West Virginia joined the Union as an independent state. Francis Pierpont, Governor of the Restored Government of Virginia, relocated the capital to Alexandria. The last move of the Restored Government of Virginia was back to Richmond in 1865, after the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia and the dissolution of the Confederacy.

Confederate officials fled Richmond on April 2, 1865 after Robert E. Lee reported that the Union Army had broken through the defenses at Petersburg. The Confederate Cabinet met briefly in Danville between April 6-10, 1865. The move to Danville was a shift of the seat of the Confederate government, but not a shift of the Virginia state capital.

much of Richmond's business district was burned in the 1865 Evacuation Fire

Source: Library of Congress, Ruins of the water wheel in Gallego Flour Mills, Richmond, Va. (by Alfred R. Waud, 1865)

The Sutherlin Mansion (now the home of the Danville Museum of Fine Arts & History) was the last "capitol" in the last "capital" of the Confederacy. The Confederate Congress never assembled there, but it was the location where Jefferson Davis last hosted a cabinet meeting and from which he issued his last formal proclamation.

That history has made the mansion a modern tourist attraction, and also the center of controversy. The City of Danville acquired the building and made it into the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History, and flew the Confederate flag in the front yard of the mansion. Residents in the city, in which half of the population was classified by the 2010 Census as "Black or African American alone," objected. When city officials removed the flag, the Sons of Confederate Veterans sued to have it restored as a war memorial.8

The dispute centered around how the Confederate government's last formal meeting would be recognized. Virginia's governor and General Assembly never tried to use Danville as a new center of state government. Richmond's business district was burned at the end of the Civil War, but the state government has stayed in that location ever since 1865.

the Confederate Congress last met in the Sutherlin Mansion, making Danville the last capital of the Confederacy - but Danville has never been the state capital

Source: Wikipedia, Danville, Virginia

At the Federal Level, Washington DC is the capital city and the US Congress meets in the Capitol building. Charlottesville (May/June, 1781), Staunton (June, 1781), and Lynchburg (April, 1865) could claim to have served briefly as the capital city of Virginia, since the General Assembly met there officially at least to do business. The state legislature has also convened in Williamsburg since 1865, but those were ceremonial sessions.

The colonial and then state capital migrated from Jamestown to Williamsburg to Richmond. The capital could have moved again after 1780 to a more-central location, as population grew in the western part of the state after the American Revolution. One obvious possibility was Lynchburg. It was closer to Virginians living in the Mississippi River watershed, easily accessible from the east via the James River, and had good transportation connections to the north and south.

Virginia politics prior to the Civil War reflected the increased frustration of residents living west of the Fall Line, as the eastern counties maintained control over the General Assembly. The power of Tidewater politicians ensured the capital would stay in Richmond, leading ultimately to 33 western counties seceding from Virginia when the Civil War created the opportunity.

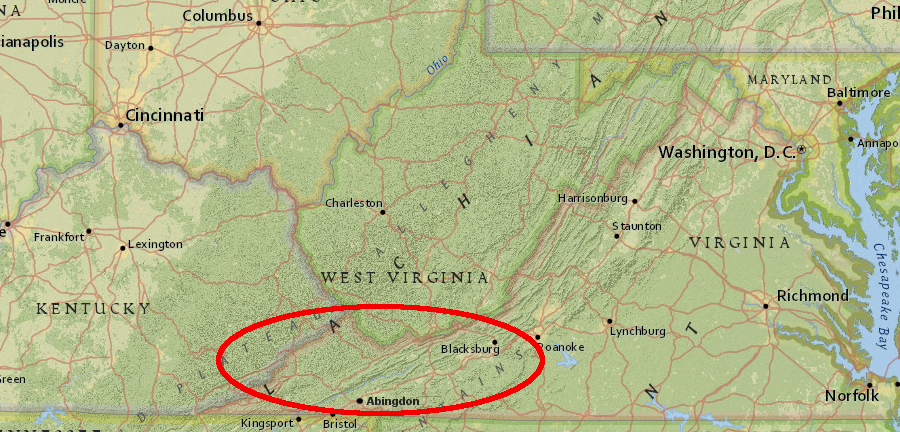

After the creation of West Virginia, the counties of Southwest Virginia remained far from the state capital. The thin population of that most-distant region, and its evolution into a non-competitive region that votes reliably for Republicans, has led to arguments that it is ignored by the candidates for office and those who get elected.

Most political visits to Southwest Virginia stopped at Roanoke, the only place in the region with a major TV market and an airport with commercial passenger service. It is a two-hour drive to get from Roanoke to Abingdon; three hours to get to Grundy, the county seat of Buchanan County. Local and regional leaders argue that the disconnect has limited the state's efforts to revitalize the region's economy and replace employment based on coal.

In 2017, The Roanoke Times published an editorial with a proposed solution: create a second home for the governor in Southwest Virginia. After all, North Carolina has a Governor's Western Residence in Asheville. In 1964, it was:9

The Roanoke Times did not propose that capital move from Richmond or that the General Assembly meet in Southwestern Virginia, but for at least a portion of the year the governor and his/her top appointees would spend time west of the Blue Ridge. The editorial suggested that getting the governor to wake up occasionally in Southwest Virginia was the best that could be expected. Politicians from the region were not likely to win statewide office, and political realities would continue to consign Southwest Virginia to relative oblivion:10

a second residence/office for the governor in Southwestern Virginia would be approximately 300 miles west of Richmond

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 2018, the Roanoke newspaper returned to the theme that the politicians in Richmond are ignoring Southwest Virginia because the capital is so far distant from the region. An editorial highlighted maps produced by Brian Brettschneider, a climate researcher in Alaska. He determined that Virginia is the only state with a region that is closer to capitals of eight other states. That included all of Lee County, much of Wise and Scott counties, and the city of Norton.

The last eight miles of the far southwestern tip of Virginia, from Ewing to Cumberland Gap at the western edge of Lee County, is closer to nine other state capitals than to Richmond:11

It is also true that Tyson Corner in Northern Virginia is closer to Annapolis, Maryland and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Nearness to another state's capital may not affect policy decisions for a region, but distance away from Richmond could have an impact.

Odds are good that a high percentage of members of the General Assembly and the executive branch of state government are familiarized with the traffic and other issues of Northern Virginia, as they travel regularly to Washington DC and points north. Legislators are less often traveling through Southwest Virginia, in contrast. Creating sensitivity to that region's concerns, and a sense of urgency to address them, is a constant challenge for the elected officials - and evidently the Roanoke newspaper.

last five locations of the capitals of Virginia

Map source: USGS National Atlas

in 1865 the Capitol building in Richmond still resembled the original structure erected according to Thomas Jefferson's design, and a main entrance was on the west side rather than through the front (with the columns)

Source: Library of Congress, Capitol building