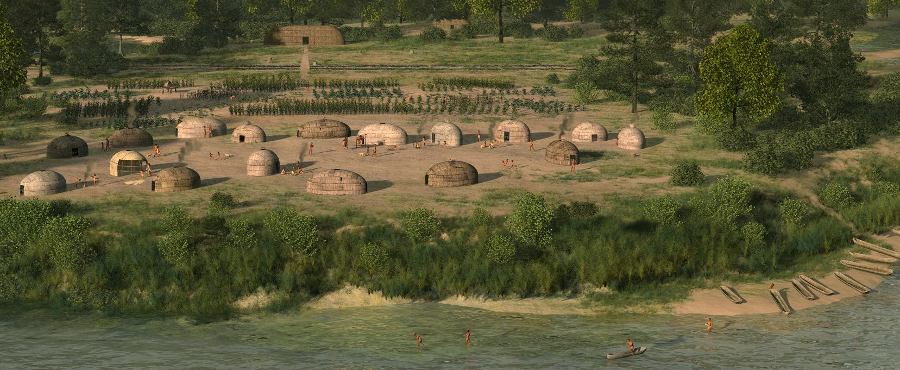

Werowocomoco was the cultural and religious center when Powhatan was paramount chief, before the English arrived in 1607

Source: National Park Service, Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail

Werowocomoco was the cultural and religious center when Powhatan was paramount chief, before the English arrived in 1607

Source: National Park Service, Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail

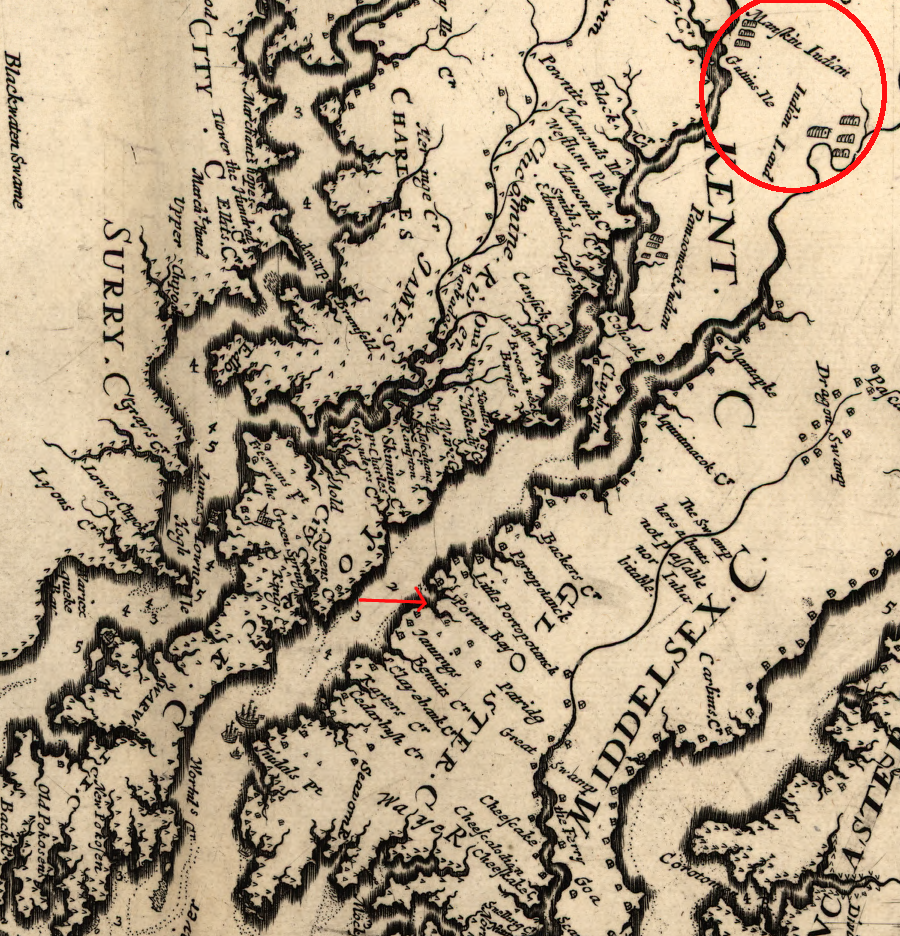

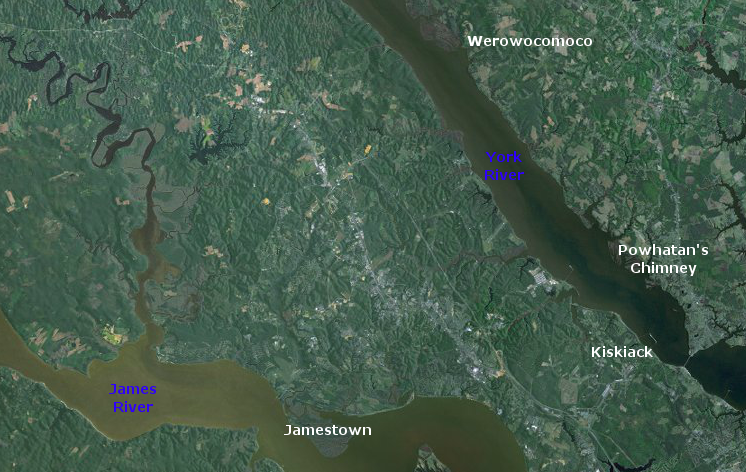

Virginia's first known capital was Werowocomoco, on the north bank of the river known as the Pamaunke until the English re-named it the York River. From it, Wahunsunacock (known to the English as Powhatan) controlled his territory.

It was called Tsenacomoco or Tsenacommacah, meaning "densely inhabited place." The English who arrived in 1607 called their territory Virginia, after their unmarried queen located in London.

The colonists quickly discovered that Powhatan was a paramount chief for over 30 Algonquian-speaking tribes. He appointed most weroances (lesser chiefs) living in Tidewater Virginia between the Aquia/Potomac creeks to the Elizabeth River.

He was born around 1550 at the town of Powhatan, which was located on the eastern edge of modern-day Richmond (perhaps at Tree Hill Farm) near the falls of the James River.1

His family, presumably an uncle, already had authority over the tribe living in that town plus five other tribes located near modern-day Richmond and Ashland - the Arrohothateck, Appamattuck, Mattaponi, Pamunkey, and Youghtanund. Before the English arrived, Powhatan inherited that power and then gained control over other towns living along the protein-rich York River and James River.

He expanded his power to the east, where other tribes also spoke an Algonquian language and were more willing to accept his authority. The Monacan living west of the Fall Line spoke a Siouan language and remained hostile.

Before the English arrived, Powhatan moved east and established his capital or "seat" at Werowocomoco. Choosing that location on the York River moved his place of authority from the western edge of Tsenacommacah closer to the center. Werowocomoco, which means "place of leadership," could have acquire its name as a result of that shift.2

expansion of territory over which Powhatan sought to exert control (Werowocomoco was not located in his original territory)

Source: Ray Sterner, Color Landform Atlas of the United States - Eastern Virginia

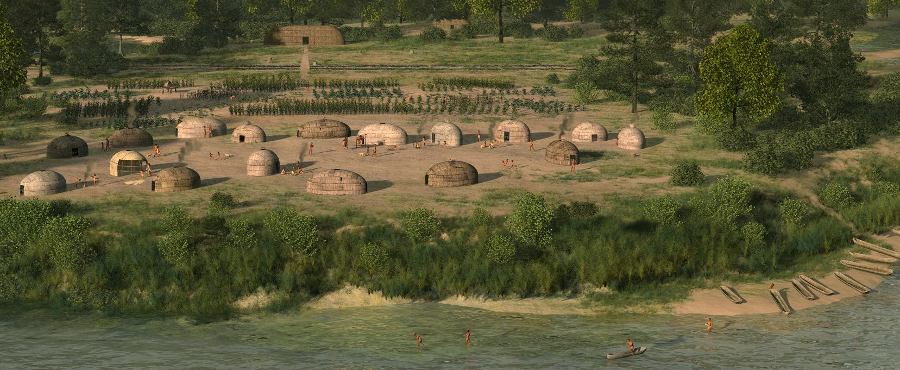

Though Christopher Newport, John Smith, and other early colonists visited Werowocomoco and clearly recognized it as an important site, the location of Powhatan's primary town was "lost" by the mid-1800's. Augustine Herrman's 1670 map recorded the location of Native American settlements upstream of Werowocomoco recently owned by the Queen of the Pamunkeys, but omitted the name Werowocomoco.3

the area occupied by the Manskin (Pamunkeys) was noted, but Werowocomoco was not recorded on Augustine Herrman's 1670 map

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman)

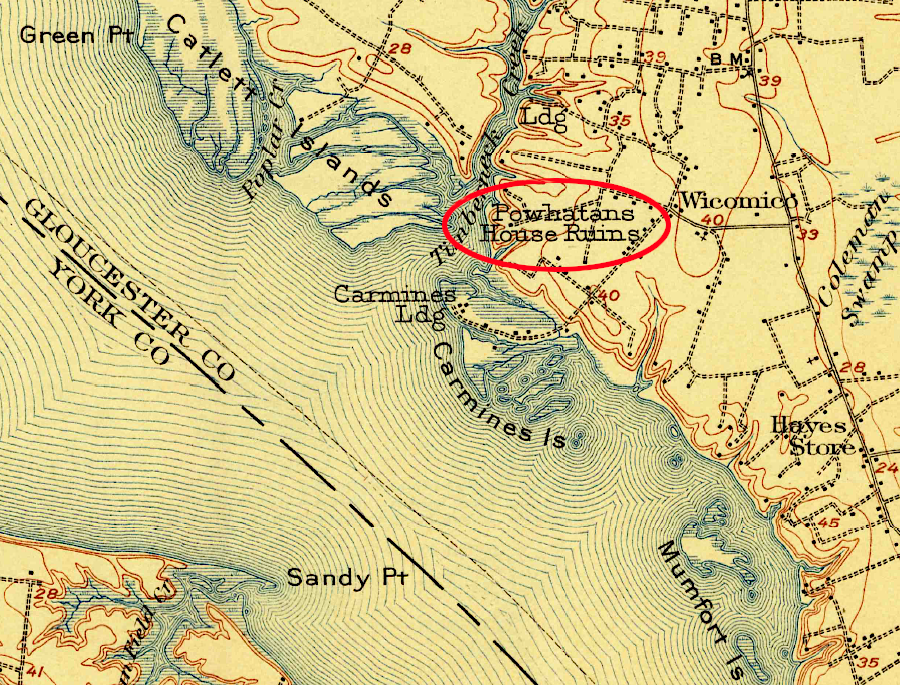

According to local tradition in Gloucester County, Werowocomoco was located at modern-day Wicomico on Timberneck Creek, where an old chimney supposedly marked the remains of a house built for Powhatan by the English.

The location of Werowocomoco was known in 1890, more than a century before archeologists documented the specific site, when Alexander Brown published The Genesis of the United States. He recognized from historic maps, including the 1608 Zuniga map, that the town was on Purtan Bay - 10 miles upstream from Timberneck Creek.

Powhatan's Chimney on Timberneck Creek collapsed in 1888. Failure to maintain the relict chimney led to the creation of the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA). That non-government organization, now known as Preservation Virginia, has played a key role in saving Jamestown Island and various historic sites associated with English colonial gentry.

Powhatan's Chimney was once thought to mark the location of Werowocomoco

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Williamsburg VA 1:62,500 topographic quadrangle (1906)

One author highlighted in 1893 why such an organization was needed:4

The Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities rebuilt the chimney in the 1930's. The organization focused on the heritage of the English colonists, but was also interested in the "kingly wigwam" of the father of Pocahontas.

Powhatan's Chimney on Timberneck Creek was once thought to be the location of Werowocomoco

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service Wetlands Mapper

Powhatan moved his capital away from Werowocomoco in 1609. In 2003, archeologists announced that the actual site was on Purtan Bay, in modern Gloucester County. Though everyone knew that Powhatan's capital was somewhere on the north bank of the York River, placing Werowocomoco that far upstream from the mouth of the York River was a revelation for some local residents.5

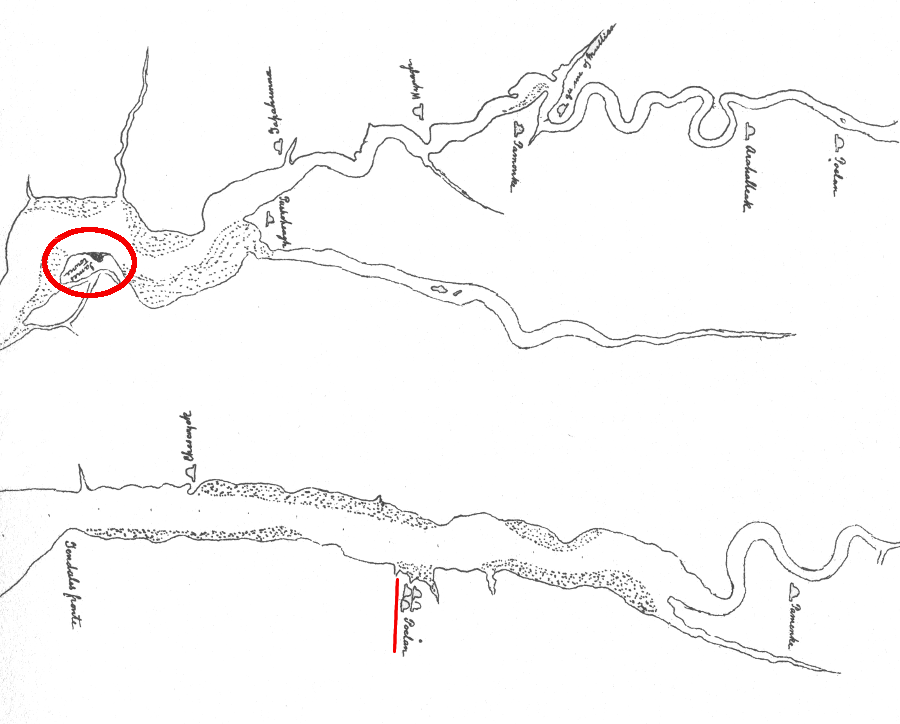

location of Werowocomoco on John Smith's map

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

According to John Smith, Werowocomoco is where Pocahontas came to his rescue at the beginning of 1608. Smith had been captured by Powhatan's brother Opechancanough while hunting on the Chickahominy River, and Smith was carried to various villages before being brought before Powhatan himself at his longhouse in Werowocomoco.

Robert Tindall identified James Town and Native American towns on the James and York rivers (Werowocomoco was labeled as "Poetan") on his 1608 map

Source: She-philosopher.com, Robert Tindall's Chart of the James and York Rivers, 1608

John Smith was the first European to see the place. He visited it a total of five times, including a visit with Christopher Newport to crown Powhatan. The colonists always came to Werowocomoco to see Powhatan; he never went to Jamestown. Captain Newport had thought he had met Powhatan on his first visit to the Fall Line on the James River, but he was confusing the weroance in charge of the town of Powhatan (Parahunt) with the paramount chief himself.6

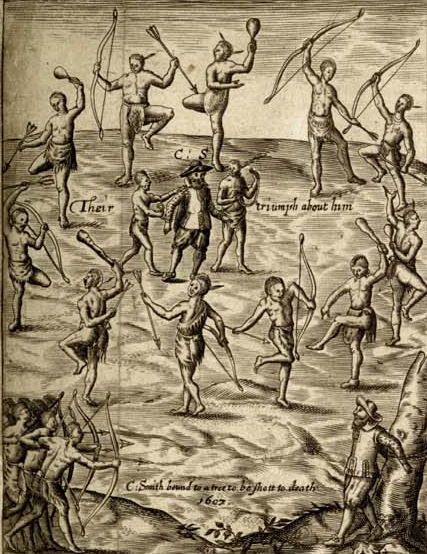

John Smith was captured by Opechancanough, while hunting near the headwaters of the Chickahominy River,

and ultimately taken to Powhatan at Werowocomoco

Source: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles

Smith wrote his version in 1624, when anyone who might have disputed it was dead. According to the unverifiable 1624 story, Powhatan was conducting either an execution or a ritual that started with a special meal and could have ended with John Smith's head being smashed against a rock, but Pocahontas intervened:7

if John Smith really was rescued by Pocahontas, there would not have been any Great Plains teepees at the site, and the Native American clothing would have been animal skins...

Source: Library of Congress, Pocahontas saving the life of Capt. John Smith (1870 chromolithograph)

Today the reservations of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi tribes are located on tributaries of the York River in King William County. The chief and council of the Pamunkey tribe is centered on a reservation on the Pamunkey River. The Mattaponi reservation is nearby on the Mattaponi River. Both are upstream from Powhatan's old capital at Werowocomoco, and west of the modern community of West Point where the York River is formed by its two tributaries.

modern reservations for Pamunkey and Mattaponi tribes are upstream from West Point, at the confluence of Mattaponi and Pamunkey rivers

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service Wetlands Mapper

In the days before the English arrived in 1607, Werowocomoco was the capital of just one Algonquian paramount chiefdom, Tsenacommacah.

Werowocomoco was never the capital of all of Virginia. The Iroquoian-speaking Nottaway and Meherrin south of today's James River, the Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee in southwestern Virginia, and the Siouan-speaking Monacan and Manahoac upstream of the Fall Line owed no allegiance to Powhatan.

Powhatan's span of control did not include 100% of Tidewater Virginia. Commands issued by Powhatan from Werowocomoco were not mandates that all Native American groups in Virginia had to obey.

Tsenacommacah extended along the south bank of "Powhatan's river" (today's James River) up to the Rappahannock River, and perhaps included towns on the southern bank of the Potomac River downstream from modern-day Colonial Beach. The tayac of the Piscataway had control over a separate set of towns on the southern bank of the Potomac River, including the Dogue tribe with its main town of Tauxenant at the mouth of the Occoquan River. The Algonquian-speaking tribes in what is now Northern Virginia (north of Fredericksburg) did not consider Powhatan to be their paramount chief.

Before the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery sailed into the Powhatan River, Powhatan had not consolidated control even over all territory on the peninsula between what we now call the James and York rivers. When Jamestown was established in 1607, the Chickahominy tribe, located on the Chickahominy River in the center of Powhatan's territory, was allied with - but not controlled by - Powhatan. He appointed the chiefs in the towns he controlled in Tsenacommacah, but Powhatan did not appoint the members of the council that governed the Chickahominy.

The Rappahannock River may have defined some border of Powhatan's Tsenacommacah when the English arrived. Powhatan considered the Patawomeck at Aquia/Potomac creeks to be subordinate to him, but his claim was tenuous. The Patawomeck managed to free themselves from obligations to pay tribute to Powhatan in 1613. That year, Patawomeck chief Japasaws conspired with a visiting English ship captain and helped him kidnap Pocahontas. If Powhatan retaliated against the Patawomeck, the English did not hear of it or document such a response.

Purtan Bay, site of Powhatan's capital Werowocomoco (red X) until 1609

Source: USGS Digital Raster Graphic, GeoTIFF of 1:24,000 Gressitt Quad (from Radford University GIS Center Spatial Data Server)

The arrival of the English disrupted the power structure in Tidewater Virginia. Two years after Jamestown was settled, Powhatan moved his capital. He abandoned Werowocomoco in 1609 and moved his capital to Orapakes, to get further away from the English colonists.

The immediate trigger for abandoning the site was a raid by John Smith. Powhatan had offered to provide food in exchange for the English building him a house and providing him swords and guns.

Smith sent by land some German glassmakers and over a dozen English workers to start building the house, while he sailed there on the Discovery accompanied by two barges. On the way down the James River the Warraskoyack chief warned John Smith that Powhatan was planning an ambush, but Smith was willing to take the risk in order to get the food.

After sailing and rowing the Discovery to Werowocomoco, Smith negotiated/displace sufficient force to get some corn loaded on his three boats. However, Pocahontas warned Smith that the Germans who had been sent to build Powhatan's house had switched sides. They must have assessed the quality of life if they returned to Jamestown vs. living in the Native American capital, and chose the Native American culture. It had less technology, but offered more food and more opportunity for female companionship.

In response to the warning, Smith made clear that the English were ready to fight if necessary. He then led the Discovery and barges further upstream on the Pamunkey River to acquire more corn from Opechancanough. That trade also involved both negotiation and force. At one point, Smith grabbed Opechancanough by the hair and shoved a pistol next to his chest to deter a planned attack.

On the way downstream, Smith met an Englishman who had come from Jamestown with news that two members of the council had drowned. Their deaths left the council with just Smith and one other person, and as president of the council Smith had two votes. That meant he could make official decisions on his own initiative now, and he determined to return to Werowocomoco with a surprise attack.

Powhatan anticipated the threat, perhaps alerted by the colonists who had chosen to switch sides. When Smith reached Werowocomoco, the "place of chiefs" occupied for the last three centuries was empty. Powhatan had left, and permanently shifted his "seat" to Orapakes.8

Archeological investigations have documented that site 44GL32 is the location of Werowocomoco at Purtan Bay, between Leigh Creek and Bland Creek. The site could date to the 13th Century. Long before Powhatan was born or the English arrived, Werowocomoco was significant in Native American culture.9

three creeks flow into Purtan Bay, where Werowocomoco is located

Source: US Geological Survey, Gressit 7.5x7.5 topographic map

In addition to the artifacts expected from excavation of a standard Native American town, archeologists have discovered other evidence that Werowocomoco was designed as a special, sacred place. Ditches, an unusual feature in Algonquian towns, separated the sacred site from the "normal" town. As described in the nomination of Werowocomoco to National Register of Historic Places:10

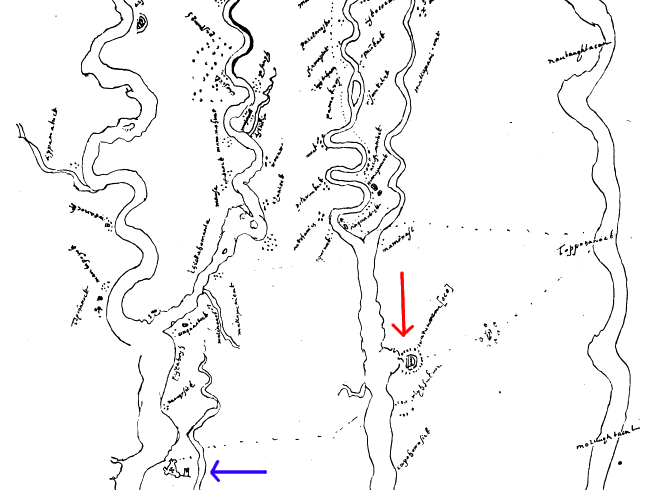

Werowocomoco on York River, with ditches identified by dotted lines on Zuniga Map - see close-up

(Jamestown identified by triangular fort, marked by blue arrow)

Source: Werowocomoco Research Project Virtual Visit

Why did it take so long to "find" Werowocomoco? The site at Purtan Bay was not threatened by development, so confirming suspicions that it was the location of Powhatan's capital was not a high priority for archeologists. They made casual visits to contact the landowners starting in 1977, but never managed to catch them at home.

The location was examined closely only after the landowner began to place riprap on the shoreline. Fairfield Foundation archeologists met with the property owners in 2001, and contacted the Virginia Department of Historic Resources after seeing artifacts that had been collected on the surface. After being alerted by historians and archeologists about the site's unique value, landowners Bob and Lynn Ripley were extraordinarily supportive. They even funded the initial archeological site survey.

Before digging at the site, archeologists consulted with the eight tribes that were then recognized by the state of Virginia, to determine their research priorities and concerns. How to handle any human remains was discussed, though the American Indian Graves Protection and Repatriation Act did not apply since no Virginia tribes were Federally recognized at the time.

The tribes posed one particularly valuable question that helped shape the research: what was on the site before Powhatan's capital?

Excavations were conducted in 2003-07 and again in 2010. To define the boundaries of the area that had been occupied by Native Americans, archeologists dug over 600 shovel test pits 1-foot wide in diameter, every 50 feet. Late Woodland sites are typically 5-10 acres. Werowocomoco includes at least 50 acres of occupied land, and there were artifacts found as much as 1,500 feet inland from the shoreline.

Archeologists also dug 1.5-2 feet deep into subsoil in the ditches, which were found by good luck during the 2003 excavation. They discovered evidence of an unusually large structure, 20' wide by at least 70' long, when typical Algonquian homes were only 10-18' wide x 30' long.

The structure was distinctively unusual, and its site was identified thanks to the surface collection of copper pieces by the landowners. The archeologist from the Virginia Department of Historic Resources separated the collected copper into two types, identifying one that he thought would date to the era when Christopher Newport and John Smith were trading with Powhatan. The landowner then commented that all that type of copper was found at one specific location.

Two bands of dark soil up to 5' wide and 1-3' deep matched the outline of trenches shown on the Zuniga map. The bands are 4-7' apart and remain parallel. No other Native American site in Tidewater Virginia has trenches, other than those in which trees were inserted to create a defensive palisade. There are no postholes in the trenches at Werowocomoco, so they were a highly-visible earthwork rather than a defensive fortification.

Radiocarbon dates from charcoal and corn indicate a small trench, separate from two parallel ones, dated to 1200CE. The parallel trenches dated back to 1350CE, suggesting the site was a sacred center for 350 years before Powhatan was born.

Archeologists identified a gap in the trenches. That may indicate an entrance from the secular town along the river's shoreline to the sacred area. The gap lines up with the unusually-large longhouse at the summer solstice.11

the area behind the trenches, potentially the sacred zone and residence of Powhatan, was set back from the secular town next to the river

Source: Werowocomoco Research Project, Werowocomoco: A Powhatan Place of Power

Powhatan may have moved to the site around 1590 when he was around 40 years old. At the time, he would have been consolidating his authority over recently-conquered tribes on the Coastal Plain, establishing his power within Tsenacommacah. Moving to the sacred center would have associated his earthly control with the spiritual powers concentrated there. If that was his intent, he had an alternative to Werowocomoco. Powhatan could have moved his capital to Uttamusack, the religious temple complex near West Point.

The location of Werowocomoco could have determined where Spanish missionaries settled in 1570. They landed on the north bank of the James River, but chose to walk across the Peninsula to the south bank of the York River to Kiskiak (which is now within the boundaries of the Yorktown Naval Weapons Station. The missionaries may have chosen to locate at that site for the same reason as Powhatan chose Werowocomoco: to be near the ceremonial center of the Native Americans living in that area.

Source: Chesapeake Conservancy, Werowocomoco: A Powhatan Place of Power

In 1570, the existence of Powhatan may have been unknown to the Spanish. He was only 20 years old, and his uncle may still have been in control of the six towns near the Fall Line that became the starting point for Powhatan's paramount chiefdom. However, missionaries seeking to convert Native Americans to the Catholic faith may have learned quickly that Werowocomoco was a key place in the spiritual beliefs of the "pagans," and selected Kiskiak to help challenge those spiritual beliefs more directly.

John Smith was captured and brought to see Powhatan at Werowocomoco in January 1608. That is the place where Pocahontas supposedly rescued him.

When the College of William and Mary formally announced the discovery of Werowocomoco, no mention was made in the news release or at the news conference that Pocahontas was associated with the place. The university considered the site to be significant primarily due to its association with Powhatan and its long occupation as a spiritual center.

Nonetheless, her "saving" of John Smith dominated the news coverage after the announcement of the discovery. The interaction between Algonquian and English cultures 400 years ago involved complex political, economic, and social challenges, but a simplified tale popularized in a 1995 Disney movie shaped the reaction of the reporters. They recognized what the public would find most interesting.

As described in the first paragraphs of the New York Times story on the discovery of Werowocomoco:12

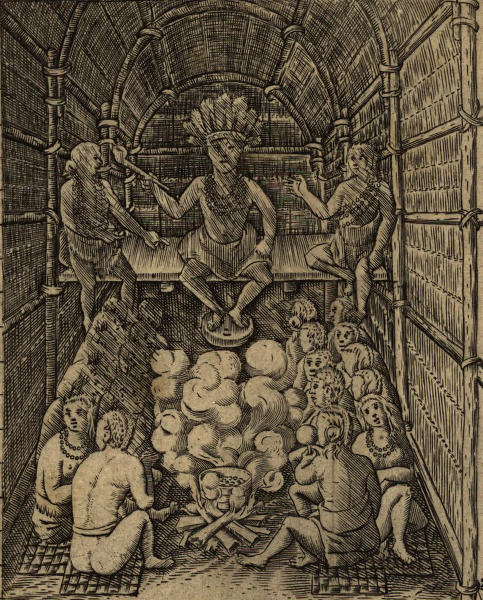

Powhatan in his longhouse, prepared to greet John Smith

Source: Library of Congress, John Smith's map

When the governor of Virginia announced in 2013 that the landowners had signed a conservation easement to protect the 58-acre site in perpetuity, once again the news release focused on the long-term significance of the site rather than the short period when Pocahontas lived at Werowocomoco. The June 21, 2013 news release was titled:13

On the other hand, whoever wrote the news release was careful not to "bury the lead," recognizing that the general public has more awareness of Pocahontas than of the religious/political significance of the site for 400 years. The first sentence in that news release was:

150 years after John Smith visited Werowocomoco, the only place name at the site recorded on the Fry-Jefferson map was "Portan Bay"

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1757)

exhibit showing frame and coating of Algonquian dwelling at 2009 State Fair... with tractors and Ferris wheel in background (using reed mats saves significant time in reconstruction, but affects the authenticity of the reconstruction)