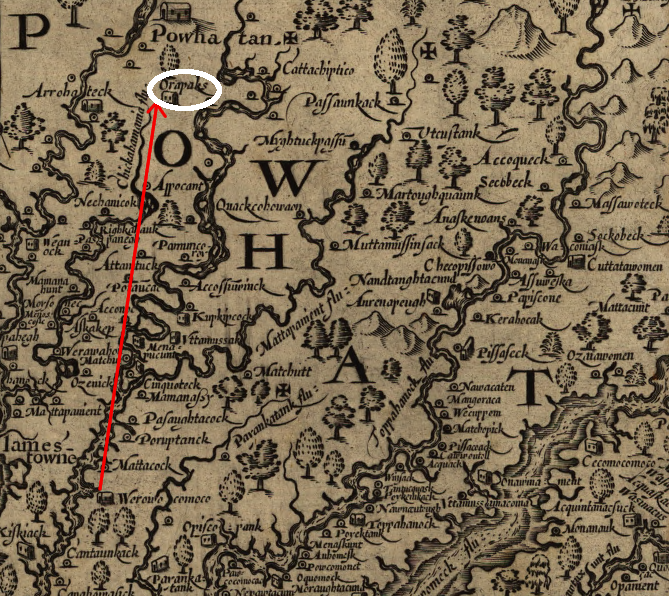

Orapakes, on the Chickahominy River

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

Orapakes, on the Chickahominy River

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

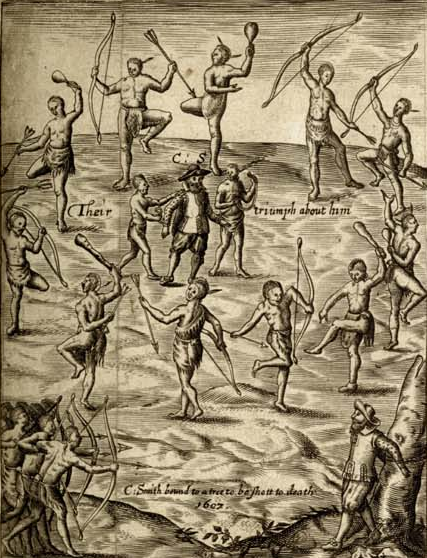

In 1607, John Smith was the first European to visit Orapakes. He had been caputured while exploring up the Chickahominy River, and his two companions were killed. The Native American hunters were prepared to kill Smith as well, but he claims that he dazzled Opechancanough by displaying his compass and giving an oration about " the roundnesse of the earth, and skies, the spheare of the Sunne, Moone, and Starres, and how the Sunne did chase the night round about the world continually."

John Smith was captured on the Chickahominy River in December 1607, then brought to Orapakes

Source: University of North Carolina - Documenting the American South, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles (p.18a)

When Opechancanough held up the compass for all to see, "they all laid downe their Bowes and Arrowes, and in a triumphant manner led him to Orapaks, where he was after their manner kindly feasted, and well vsed." He described Orapakes as a town with "onely thirtie or fortie hunting houses made of Mats, which they remoue as they please, as we our tents."

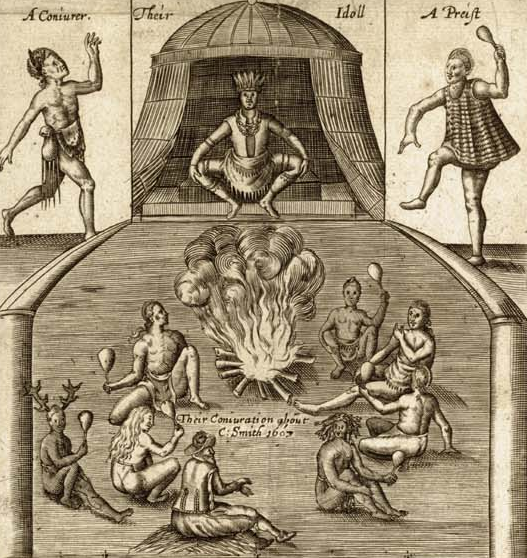

The priests and warriors conducted rituals and danced around both him and Opechancanough. He was served so much food Smith feared he was being fattened before slaughter.

John Smith experienced a a ritual of dancing and conjuration at Opechancanough's town, on the Pamunkey River between Orapakes and Werowocomoco

Source: University of North Carolina - Documenting the American South, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles (p.18a)

Smith claims that the guard prevented one of the Native Americans from assassinating him at Orapakes, and he was offered "life, libertie, land, and women" in exchange for information needed to attack Jamestown. Instead, he described how the fort's strong defenses would repel an attack.

He was marched from Orapakes to various towns in Tsenacommacah, including up to the Rappahannock River. He was then carried to Opechancanough's "habitation at Pamavnkee," and finally ended up being taken to Werowocomoco where he was "rescued" by Pocahontas.

On the journey in late 1607 and early 1608, Smith saw at least two of the three towns used as Powhatan's capital (Orapakes and Werowocomoco), plus the town where Opechancanough was the chief.1

Orapakes was Powhatan's second capital, after Werowocomoco and before Matchut

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 1609, Powhatan moved his capital from Werowcomoco to Orapakes.

Powhatan had realized that his base of operations at Werowcomoco was too exposed to the English ships sailing up the river. Werowcomoco was on the shoreline of the York River at modern-day Purtan Bay, and ships provided the English a moving wooden wall of defense against arrows.

The immediate trigger for the move to Orapakes in 1609 was a raid by John Smith. He took the Discovery and two barges to Werowocomoco, then up the Pamunkey River to Opechancanough's town to force him to provide corn. After a confrontation there with involved Smith grabbing Opechancanough by the hair to hold as a hostage in exchange for corn, Smith returned downstream to Werowocomoco.

John Smith seized Opechancanough by his hairlock at the chief's town, and obtained corn by force in 1609

Source: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles

When Smith came back downstream, Werowocomoco was empty. Powhatan's plan to establish trade at Jamestown while limiting English expansion had failed, and moving the capital gave him more options in case of a broader military conflict. The English could get directly to Werowcomoco without exposing themselves to attack on land. Orapakes, in the swamps at the headwaters of the Chickahominy River, was easier to defend.2

Here's how John Smith later described Powhatan's move to his second capital:3

Orapakes was near the modern-day interchange of I-64 and I-295, perhaps the archeological site in New Kent County labelled 44NK100. According to Helen Rountree, it was intended to be just a temporary capital. The new location of Powhatan's "seat" lacked the broad, flat river-bottoms where the Algonquians could plant corn. It was not easily accessible by canoe, and was located at the edge of his territory too close to the rival Monacans for comfort.4

Orapakes was not the preferred site for the capital of Tsenacommacah, but Powhatan moved inland to avoid the threat from a foreign enemy. Moving the capital in 1609 was comparable to the reason why the rebelling Virginians moved their capital from Williamsburg to Richmond in 1780.

Powhatan lived at Orapakes for at least two years after he moved there in 1609. He was based at Orapakes when John Ratcliffe came to trade for corn in late 1609. John Smith had been wounded by a gunpowder explosion and was incapacitated, and soon left the colony. The new president of the council, George Percy, sent Captain Ratcliffe to negotiate with Powhatan for corn. The colonists had not raised enough food on their own to survive the winter of 1609-10, which ended up being the disastrous "Starving Time."

Ratcliffe and many in his party of 50 men spent the evening in the Native American dwellings at Orapakes. The next day, they appeared to successfully trade copper and other goods for Algonquian corn, but then the Algonquians attacked.

At Orapakes, 34 English men were killed. Powhatan's warriors even attacked the English boat, and it barely managed to fight its way downriver and escape to Jamestown.

Ratcliffe himself was captured, tortured, and finally burned at the stake. His public execution was a clear contrast to how Powhatan had treated the previous English leader, John Smith, at Werowocomoco in December 1607.5

Though the reports from the English indicate Ratcliffe went to trade with Powhatan after the paramount chied had moved to Orapakes, the Chickahominy River is so narrow there that any English ship sailing directly to Powhatan's new capital would be at great risk of attack from the shoreline. Orapakes was upstream from Apocant on the Chickahominy River, the town where John Smith had left his boat in 1607 before being captured and then "rescued" by Pocahontas.

Smith reported that in late 1607, the Council had challenged his commitment or capability of traveling up the Chickahominy River. He returned to the river and his men rowed upstream. Smith reached a part of the Chickahominy River, upstream from Apocant and downstream from Orapakes, that he described in 1608 as too dangerous for their barge:6

Smith ordered barge back downstream to the town of Apocant. He left seven of his men there, and hired Native Americans to carry him and two others upstream in a narrower canoe. He claims he went 12 miles further upstream before he was captured and taken to Orapakes and ultimately Werowocomoco.

John Smith's mileage calculations exceed the length of the Chickahominy River, but his reports make clear that Orapakes was upstream of a location that Smith considered too narrow for safe navigation. The English paid a heavy price for ignoring how that site could be defended. John Ratcliffe's decision to take a boat past the point where Smith traded his barge for a canoe, all the way to Orapakes, was as reckless as his behavior on land where his men were ambushed.

Orapakes was intended to be a refuge, safer than Werowocomoco if less suitable for Powhatan's capital. Ratcliffe's arrival made clear that the upper Chickahominy River was not safe from the English ships.

moving from Werowocomoco to Orapakes on the Chickahominy River placed Powhatan's capital in the James River watershed

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

Sometime between 1611 and 1614, Powhatan moved his capital again to Matchut. In contrast to Orapakes, Matchut offered flat terraces for growing corn, and travel by canoe was easier to the majority of Tsenacommacah. Canoes going down the Chickahominy River ended up in the James River, already dominated by English ships. Matchut was on the more-accessible Youghtanund (Pamunkey) River, and canoes could travel on the York River with less fear of English interference.

Perhaps not coincidentally, Powhatan's third capital was near where his brother/cousin Opechancanough ruled at Youghtanund. As Powhatan's strategy for confining the English at Jamestown failed, Opechancanough's influence and grew. Though Powhatan agreed to a peace with the English in 1614 after Pocahontas married John Rolfe, ending the first Anglo-Powhatan War, the shift of the capital is one clue that war chief Opechancanough was gaining authority.