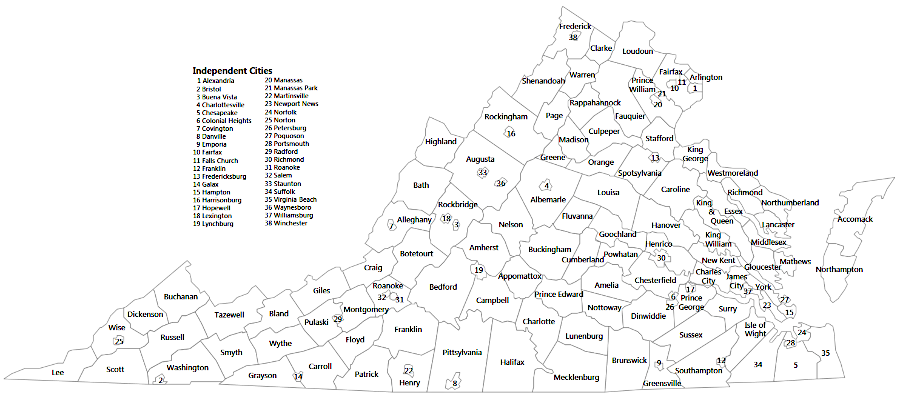

Virginia has 38 independent cities

Source: Weldon Cooper Center, Map of Virginia by Cities and Counties

Virginia has 38 independent cities

Source: Weldon Cooper Center, Map of Virginia by Cities and Counties

Virginia' first towns were created by Native Americans in the Woodland Period. Bands that had previously roamed constantly for hunting and gathering became dependent upon agricultural crops, which required regular tending and protection from grazing animals. Introduction of corn around 1,000 years ago was a factor in where permanent settlements were established, with Coastal Plain groups choosing to plant corn on floodplains with Pamunkey loam soils. Later, palisades were built around towns to protect against attack.

When Europeans arrived, the Native Americans were still engaged in hunting and gathering. In the summer, they would move to seasonal camps, where they enjoyed a change of scenery as well as opportunities to obtain different foods. Mounds of oyster shells accumulated at locations that were occupied regularly because seafood was available.

The arrival of Spanish priests in 1570 did not result in the creation of a new town; that settlement effort was too brief. If any of the English from the "Lost Colony" on Roanoke Island moved in 1587-88 to what is now Virginia Beach, they lived within existing towns of the Chesapeake tribe rather than created a European settlement.

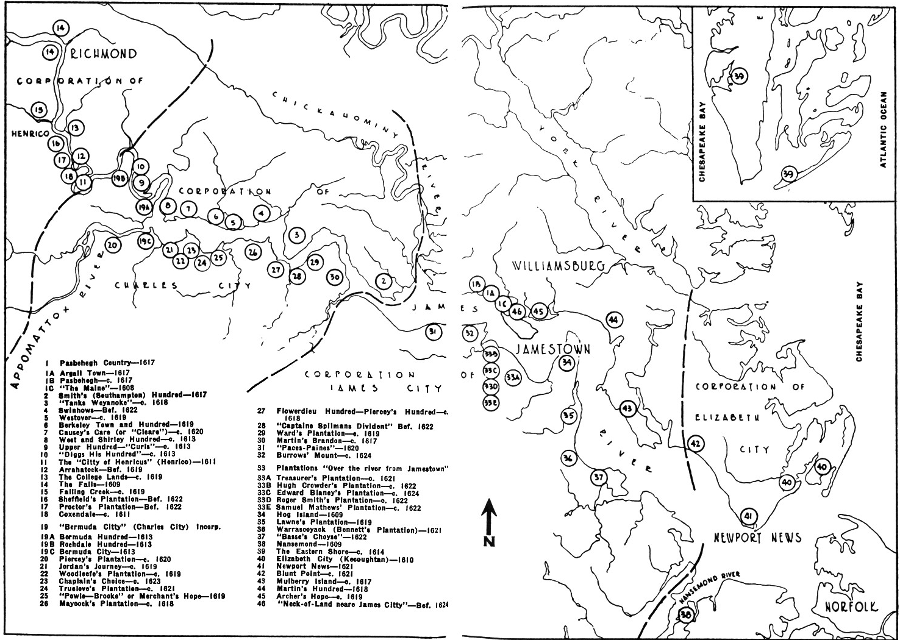

European-based town development in Virginia started with construction of a fort in 1607 on Jamestown Island. Though concentrating the men increased security in case of an attack by Native Americans or the Spanish, Captain John Smith recognized the benefits of spreading colonial settlement away from Jamestown in order to avoid exhausting the local food supply.

The first three ships which arrived there had been delayed at the start of their transatlantic journey, and some of the supplies expected to support the colony in Virginia had already been consumed. Resupply from the underfinanced London Company in England was intermittent. The colonists were not self-sufficient; they depended upon the local Native Americans for deer meat, corn, and other food. Smith left the colony in 1609, and his plans for decentralizing the settlement were not followed. Many of those remaining for the winter of 1609-10 were concentrated at the fort, and died during the Starving Time.1

In 1611, the colonists moved upriver and created Henricus, the second major English settlement in Virginia. The development of tobacco agriculture led to a dispersed settlement pattern. The London Company, which was struggling to make a profit, tried to attract new investment by granting land and authorizing the creation of "particular plantations" which were largely independent of the company's control. The company's representatives in Jamestown also maneuvered to acquire personal rights to land. Revenue from tobacco grown on private land became a personal asset rather than a company profit; the incentives for living away from Jamestown were clear.

The colonial population grew and spread out across the landscape. English farms were planted on already-cleared Native American townsites, forcing the indigenous people to move. Virginia Company officials based in Jamestown had o develop new mechanisms for managing the colony, initiating a long history of creating separate town, county, and city governments in Virginia.

Governor Samuel Argall divided the colony west of the Chesapeake Bay into the four Anglican parishes of Henrico, Kikotan, Charles City, and James City in 1617. (Kikotan, also spelled Kecoughtan, was soon renamed Elizabeth City and today has been merged into the City of Hampton.) Creating the four "incorporations" and authorizing local officials to handle some responsibilities reduced the administrative burden on officials in Jamestown.

As part of a new strategy to recruit more settlers, the London Company authorized creation of a legislative assembly in Virginia. Two representatives were chosen from each of the 11 population centers, though only 19 got to participate in the first General Assembly with Governor Sir George Yeardley and the governor's Council. The two representatives from Martin's Brandon were not seated in the assembly because John Martin's plantation had been exempted from compliance with any laws passed in Virginia.

In 1621 the Virginia Company clarified that the General Assembly would be bicameral. There would be an upper body with the Governor and his Council, and a lower House of Burgesses. The Virginia Company provided direction for electing two burgesses from every town and particular plantation.2

There were no chartered towns in the 1600's, but at least the "particular plantations" could be identified separately because the Virginia Company had issued separate grants for them. It appears there was a colonial consensus on what concentrations of settlers should be represented in the House of Burgesses, and flexibility in the number of representatives based on population.

In the 1623/24 legislature, there were two representatives from one settlement in the Incorporation of Henrico, two representatives representing all of the Eastern Shore, and four representatives from two settlements in the Incorporation of Elizabeth City. There were also seven representatives from five settlements in the Incorporation of Charles City; three settlements sent just one representative each. Similarly, from the Incorporation of James City there were 13 representatives from seven places. Jamestown had five, two settlements each had two, and four settlements had one each. In 1629, there were 24 jurisdictions entitled to elect one or more members of the House of Burgesses.3

In 1634, the General Assembly formally established the first county governments and granted authorities to those local governments. Three of the first eight counties had "city" included in their name - Charles City, James City, and Elizabeth City. At the time, the English pattern of decentralized local government did not distinguish clearly between places designated as shires, boroughs, counties, towns, and cities.

After Henry VIII separated the English church from Rome, bishops lived in places with a cathedral and those communities were typically called a "city." The bishops of the Anglican Church oversaw ecclesiastical courts, providing church officials some authority over the average English peasant. In 1634 there were no "cities" with a bishop and cathedral in Virginia by 1634, but the colonial officials had a visionary perspective of future development along the James River.

Elizabeth City County disappeared as a government unit in 1952 when it become part of the City of Hampton. The current names of Charles City County and James City County, together with Virginia's unique treatment of cities as independent political organizations completely separate from counties, creates confusion today.4

The London Company was in charge of Virginia between 1607-1624. The investors in the company determined who would serve as leaders in Jamestown. In the first years, a council in Virginia was appointed by the London Company, and the members of the council chose their leader. Starting in 1609, the company began to send specific people to serve as the top colonial leader, who became known as the governor.

By 1619, the colony was struggling to attract people willing to cross the Atlantic Ocean. The Virginia Company decided to grant the people in Virginia a role in governing the colony, starting the process that led to local government. Conversion of Virginia from a chartered private investment to a royal colony in 1624 did not slow the process. During the first century of colonization, royal officials in England did not desire to micromanage from across the Atlantic Ocean.

Virginians developed institutions to govern themselves, using English patterns as a model that could be altered to fit local circumstances. The pattern of town development in England became common in Massachusetts, but Virginia's evolving gentry of privileged families took a different approach. Virginians also created other institutions, such as chattel slavery, that bore little resemblance to any English equivalent.

Virginia colonists with wealth and connections acquired land along rivers and created large farming operations. After displacing the Native Americans and importing Africans who were forced to work without payment, the large landowners exported tobacco from wharves on their riverfront. Rivers were the primary transportation routes in the 1600's. The roads were muddy bogs after a rain, so hauling tobacco overland on a dirt farm-to-market road to a town dock was not an efficient option. Large landowners who controlled the economic, religious, social, and political institutions saw no economic incentive to centralize development and create towns.

Officials in London objected to the dispersed settlement pattern. Officials in England desired that towns be established so royal taxes and fees could be collected effectively, rather than evaded by ship captains dealing directly with the planters. The first efforts to mandate development in Virginia were provided in instructions to royal governors. They were directed to concentrate business at Jamestown and make that town the center of economic as well as government activity in the colony. While governors were technically in charge, they had to rely upon their personal influence to get the House of Burgesses to implement royal instructions. It was common for the burgesses and members of the Governor's Council to bypass royal orders, and Jamestown's growth remained stunted.

In 1662, after the restoration of Charles II to the throne in London, royal officials sent instructions to Gov. William Berkeley to create towns in the colony. The House of Burgesses responded by passing a new tax, with the revenue to be used annually to subsidize a new town. The sequence was to support growth of Jamestown the first year, followed by town creation on the York River, then the Rappahannock River, then the Potomac River, and then at Accomack on the Eastern Shore.

The effect of the act was minimal, so in 1680 Governor Culpeper was directed to try again. In the Cohabitation Act, the colonial legislature directed each of the 20 counties to acquire 50 acres at waterfront locations for development of warehouses and new residences. All exports and imports, other than cattle and food, were supposed to be transported through the designated towns. Prices were fixed by law for the shipping of tobacco from plantations to the warehouses at towns, and distant plantations were authorized to roll hogsheads to storage sites until a full cargo was collected for a sloop to transport to the town.

the 1680 Cohabitation Act required each county to build a town at a specific location

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

The burgesses in Virginia had hoped that new town development would help the colony recover from Bacon's Rebellion in 1676. The extra costs for transportation of tobacco to the planned towns and for temporary storage at warehouses were significant, however, and the costs were not offset by any clear benefits to those growing tobacco. The Cohabitation Act was suspended in 1681.

Each governor sought to spur concentrated development in towns, rather than extend agricultural sprawl. Governor Francis Howard's attempt in 1684 to get legislation through the House of Burgesses ended in failure. In 1691, new Governor Francis Nicholson managed to get an Act for Ports approved. It called for establishing 15 port towns plus five other locations for buying and selling goods.

The Act for Ports was designed to simplify the collection of tax revenue. The ship captains and merchants in England shared the same concerns as the planters in Virginia regarding costs and efficiency, and the law lasted only several years before it too was abandoned.5

As the historian Robert Beverley wrote in 1705:6

The first charter for a local government in Virginia, with authority separate from the county, was issued to Williamsburg in 1722. Norfolk obtained a charter from the General Assembly in 1736, creating a local court with a mayor and eight aldermen plus a common council. Richmond was granted authority to form a local government in 1742.

At the start of the American Revolution, three of the "boroughs" chartered in the 13 colonies were in Virginia. The first town chartered in the colonies was Agamenticus, created in the province of Maine in 1641. The last to be created under colonial government was Trenton in New Jersey, chartered in 1746.7

City Point, now part of the City of Hopewell, got its name because it was once part of Charles City County

Source: Library of Congress, The seige [sic] of Petersburg, Va

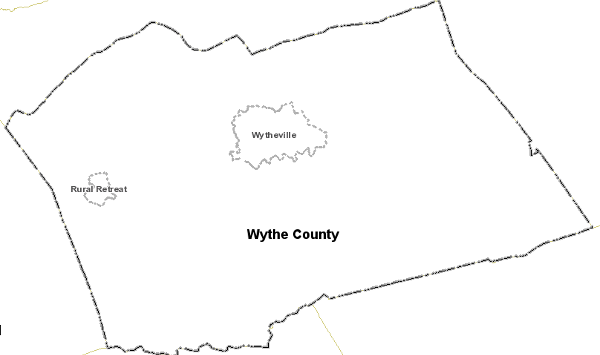

two towns are incorporated within Wythe County

Source: The First Seventeen Years - Virginia, 1607-1624

Since adoption of a new state constitution in 1870 and further clarification in its 1902 replacement, "cities" in Virginia have become completely independent from "counties." The separate status is rare in the United States. Of the 3,141 counties and county equivalents in the country, there are only three independent cities outside of Virginia - Baltimore, Maryland; St. Louis, Missouri; and Carson City, Nevada.8

In 2020 there were 38 cities in Virginia, plus 95 separate counties. There were 191 towns in the state.9

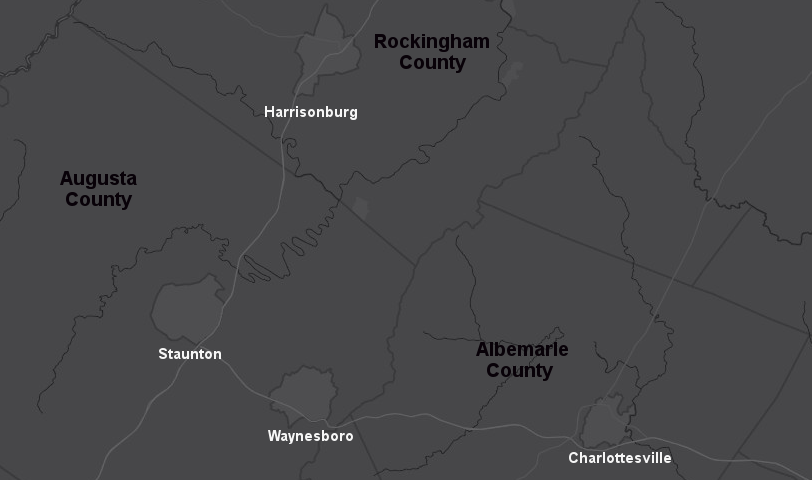

All Virginia cities are totally separate jurisdictions from adjacent counties, even if a city is located completely within a county's boundaries. Staunton and Waynesboro are surrounded by Augusta County, but the cities are distinct municipal governments with their own separate city charters issued by the General Assembly.

Staunton, Waynesboro, Charlottesville, and Harrisonburg are independent cities surrounded by counties

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Geographic proximity obviously creates opportunities for cities and counties to share costs for utilities, jails, and various government services, but local officials jealously guard their authority to make independent decisions.

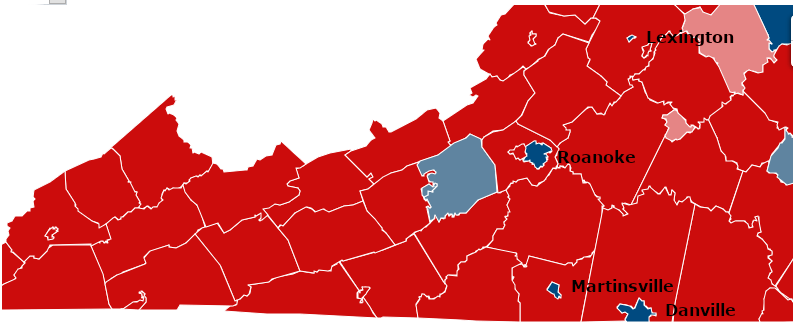

Politics is a factor in some cases. Martinsville voted 60% for the Hilary Clinton in 2016, while the surrounding Henry County gave her only 34%. Voters in the two jurisdictions have a different perspective on the role of government, and as a result the local officials in the city/county have different priorities. City and county officials are reluctant to consolidate the governments even though they might reduce the costs of maintaining an independent city separate from the county.10

Roanoke, Lexington, Danville, and Martinsburg voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016, while the surrounding counties voted for Donald Trump

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, VPAP Visuals - 2016 US President: General Election

Residents of Virginia cities vote for city council members, pay city real estate and city personal property taxes, and get business/professional licenses from city officials. In 22 of the 38 cities in Virginia, including Lynchburg, Harrisonburg, and Charlottesville, voters directly elect who will be mayor. In the other 16 cities, members of city council choose among themselves who will become mayor. Sometimes the person winning the most votes is chosen, and sometimes other factors determine who will be selected.11

City residents do not vote for county supervisors, and city residents do not pay county taxes.

If a Virginia city annexes land from a Virginia county, then the residents in the annexed area become city residents. They lose the right to vote for county officials, but no longer have to pay county taxes either. Annexation does not affect obligations to state and Federal governments; the requirements to pay state and Federal taxes are not altered by local annexation actions.

"Towns" are also incorporated jurisdictions with a charter from the General Assembly, but towns are different from cities. In Virginia, towns are not independent from counties; residents of towns are still residents of the county in which the town is located. Town residents pay town taxes and vote for town councils, but the residents also pay county taxes and vote for county officials. Town residents get double representation and double taxation.

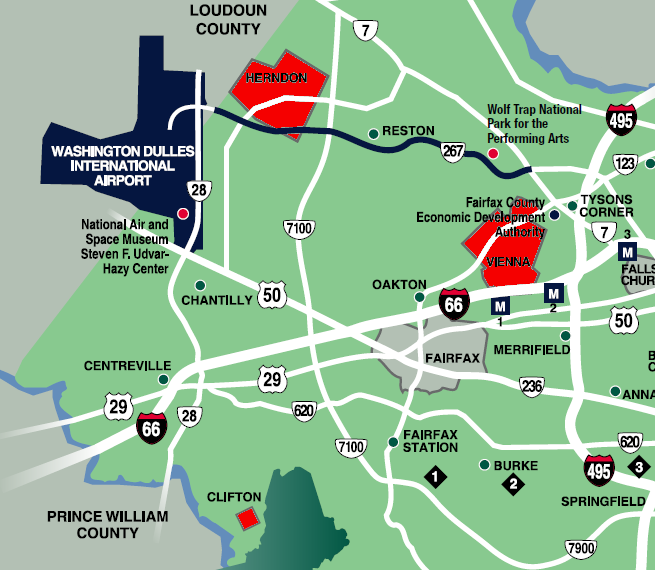

Herndon, Vienna, and Clifton are the three incorporated towns within Fairfax County

Source: Fairfax County Overview

For example, residents of the towns of Clifton, Vienna, and Herndon are also residents of Fairfax County. People living in Haymarket, Quantico, Dumfries, and Occoquan are also residents of Prince William County. Residents of the towns of Rural Retreat and Wytheville are also residents of Wythe County.

there are two towns located within Wythe County

Source: Wythe County GIS

Since 1997, Virginia has "lost" three towns. Castlewood in Russell County, Clover in Halifax County, and Columbia in Fluvanna County have abolished their town governments and became unincorporated communities within their surrounding counties.

Virginia has also gained three towns since 1995, as three cities abandoned their independent status to become towns within their surrounding counties. In 1995, South Boston became a town in Halifax County. Clifton Forge changed its status to become a town in Alleghany County, rather than a separate city, in 1991. In 2013, Bedford shifted its status from independent city to town within Bedford County.

"Towns" (such as Dumfries in Prince William County and Blacksburg in Montgomery County) and unincorporated areas with a name on the roadside (such as Centreville, Reston, and Tysons Corner in Fairfax County) are different from cities, because towns remain part of a county. Towns have a mayor and a town council, but there is no "Mayor of Reston" or "Mayor of Tysons Corner." Those places are just unincorporated portions of Fairfax County.

Reston residents vote for one member of the Fairfax Board of County Supervisors representing the Hunter Mill District, plus the chair of the Fairfax Board of County Supervisors. Tysons residents vote for one member of the Fairfax Board of County Supervisors representing the Dranesville District, plus the chair of the Fairfax Board of County Supervisors. No one in Reston or Tysons votes for town or city council members, however; those densely-populated places are not incorporated as towns or cities.

Fairfax County magisterial districts - geographic boundaries for electing 9 members of the Board of County Supervisors, plus the Chair who is elected countywide

Source: Fairfax County

Residents of unincorporated areas elect just county officials, and pay just county taxes. Residents of towns in Virginia vote for both town and county officials, and pay taxes to both the town and the county.

Some towns include land in two counties, so residents within different sections of one town will vote for officials in different counties. Divided towns include:12

- Belle Haven (Accomack and Northampton counties)

- Brodnax (Brunswick and Mecklenburg counties)

- Farmville (Prince Edward and Cumberland counties)

- Grottoes (Augusta and Rockingham counties)

- Jarratt (Greensville and Sussex counties)

- Kilmarnock (Lancaster and Northumberland counties)

- Pamplin City (a town despite the name, in Appomattox and Prince Edward counties)

- Saltville (Smyth and Washington counties)

- Scottsville (Albemarle and Fluvanna counties)

- St. Paul (Wise and Russell counties)

Unlike towns, cities are politically independent from counties. Residents of cities are NOT residents of any county in Virginia, even if the city boundaries are completely surrounded by the county.

Residents of the City of Manassas (or the separate City of Manassas Park) can not vote for members of the Prince William Board of County Supervisors. Residents of the City of Charlottesville can not vote in elections for the Albemarle County board, residents of the City of Staunton can not vote for the Augusta County board, etc.

Cities were chartered so they could provide additional services to urban areas. Dense concentrations of people needed sewer, water, fire, and police services that were not required in rural farm areas.

Charters for towns and cities have been granted by the General Assembly so local residents in densely-populated areas could tax themselves and provide the level of services appropriate for their community. That is why the General Assembly grants cities extra authority to impose taxes without a voter referendum.

Virginia's 38 cities operate their own school systems, and also must maintain their own road systems. City officials set their own priorities for repaving city highways and sidewalks, and do not have to deal with Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) officials when making most decisions on stop signs and stoplights. Within cities, VDOT does maintain the interstates and major state highways, such as Interstate 66 and Route 7 where they cut through the independent City of Falls Church.

the Town of Broadnax is located in both Brunswick and Mecklenburg counties

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The General Assembly has established an annexation process so cities/towns can expand their boundaries when population grows and development expands into nearby county lands. Since World War II, suburban shopping centers have attracted retail stores and commercial businesses away from old downtown areas, and tax revenues that formerly flowed to cities were diverted to nearby counties. Cities responded by expanding their boundaries, annexing the developed land from the county.

Cities often targeted commercial property and minimized the number of residences that would be annexed, since adding houses usually required expansion of expensive school systems. Shopping centers do not send children to school, so cities annexed the portions of counties that paid high property taxes but required few city services. Not surprisingly, county officials who faced the loss of tax revenues often fought annexation efforts by cities.

In 1975, the General Assembly imposed a moratorium that blocked most hostile annexations where cities grabbed high-value commercial property that paid more in taxes than the land required in urban services. Between 1945-1975, five counties (including Elizabeth City County) merged with their cities or had the General Assembly re-incorporate their county as a city. Becoming a city was a defensive move; cities could annex land from counties, but not from other cities.

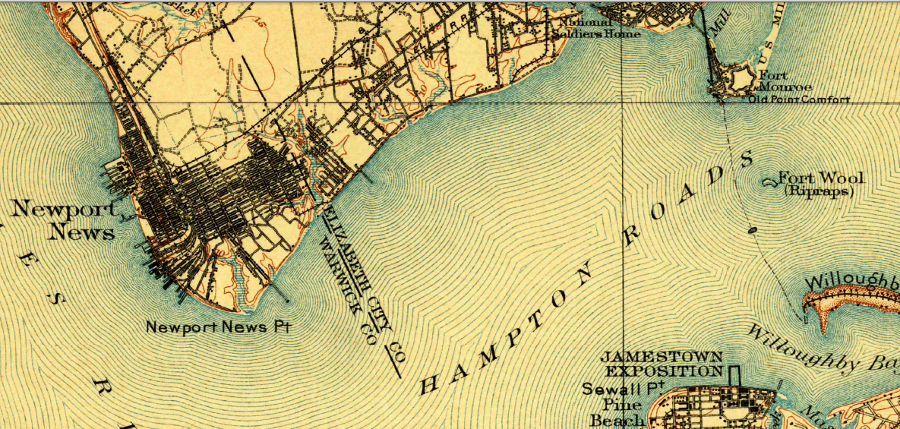

on the Peninsula, the counties of Warwick and Elizabeth City have disappeared and are now part of the cities of Newport News and Hampton

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Norfolk Special 30x30 topographic quadrangle (1907)

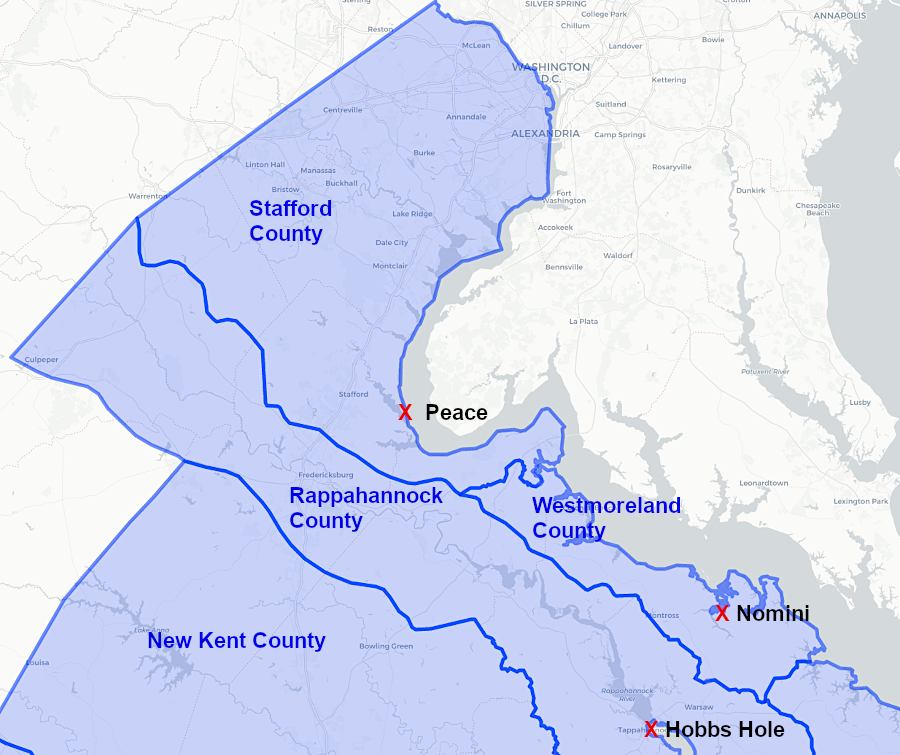

Since World War II, urbanization has expanded faster than city/town boundaries. Farming-oriented counties such as Fairfax, Loudoun, Prince William, and Stafford have been suburbanized.

Subdivisions with names such as "Franklin Farm" have replaced agriculture, the sewer, water, and road networks have been expanded, and urban-level services are offered now in large portions of the counties. There is no longer a distinction between levels of service available to residents within a town/city vs. county in Northern Virginia, Hampton Roads, or the counties surrounding Richmond.

Since 1975, many Virginia cities and counties have arranged to share services such as landfills and jails, without spending time in court disputing annexations that formally altered political boundaries.

The General Assembly encourages such regional cooperation. The deadline for water supply plans that the state mandated after the 2002 drought was extended for those jurisdictions that "partnered up" with the neighboring cities/counties. State funding for new local jails often requires a regional facility to replace separate jails in different jurisdictions.

After World War II, cities populations and tax revenues declined as middle-class and upper-class residents moved to the suburbs. Federal and state funding for new roads subsidized suburban sprawl, allowing workers to commute to job centers within the cities while living across the border in nearby counties.

The demographic shift left cities with higher percentage of lower-class residents needing more social services, but cities also had less tax revenue to provide those services. Cities could raise property tax rates to increase revenue in the short run, but higher taxes drove even more people and businesses to move away from the city.

Counties got wealthier, while cities got poorer. The cities also became concentrations of minorities as well as low-income residents, and crime rates soared. Social tensions limited the willingness of surrounding counties to assist in the revitalization of cities. When Richmond sought to meet school desegregation requirements by forcing Chesterfield County to bus white students to urban schools with a high percentage of non-white students, the Federal judge hearing the case received death threats.

When South Boston, Clifton Forge, and Bedford relinquished their charters and reverted to being just towns within their surrounding counties, they sacrificed their independence in order to spread the cost of providing urban services across the entire county. Shifting in status from city to town made county taxpayers share the cost to provide schools and other services to the former city residents.

When a city converts to a town, the city council is replaced by a town council. Town residents pay county and town taxes, with the town taxes covering additional services (such as extra police patrols) that are not provided within the county. If a town abandons its charter, then the town council is abolished and county taxpayers will absorb the cost of services in the town - though some of those services, such as extra police patrols, may be eliminated.

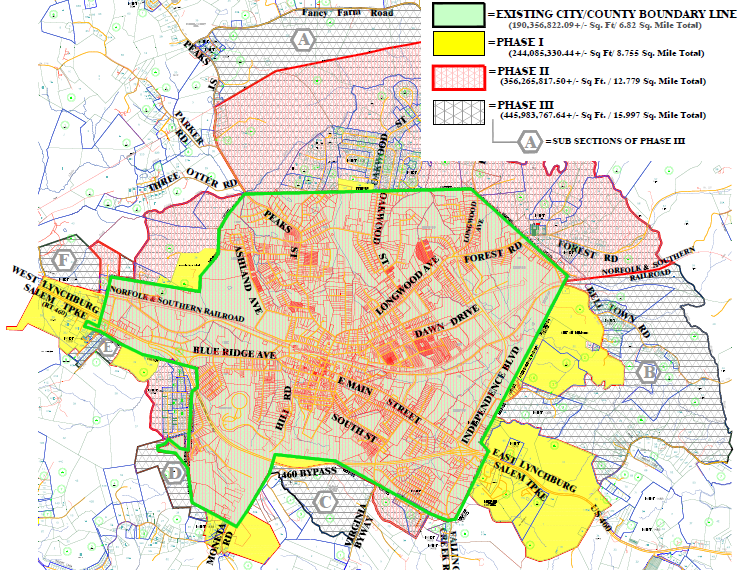

Bedford city and county sent five years to negotiate a change in status that included expanding the original city boundaries (green line) to include new parcels (yellow areas) within the town

Source: Bedford County, Reversion from City to Town Status

In 2009, Fairfax County considered asking the General Assembly to convert the county into a city. The primary issue was frustration with state delays in widening roads and building new overpasses/interchanges in Fairfax County.

As a city, Fairfax would receive a standard allocation of funds for highways, and county officials - rather than the state's Commonwealth Transportation Board - would determine what projects should receive priority. There is already a City of Fairfax, so if the county converted into a city it would have to find a new name.13

If Fairfax County became a city, then the process would include the General Assembly passing a law granting it a city charter. Under the Dillon Rule used by Virginia state courts, local communities do not have an authority unless the state legislature has clearly provided it in legislation.

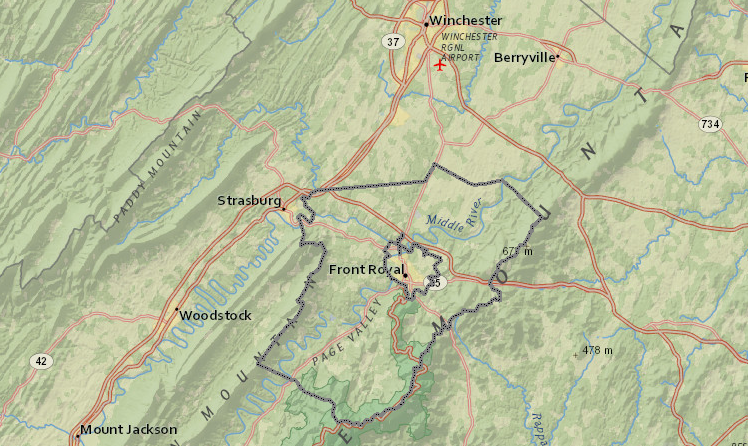

The state has granted a common set of powers to all cities and towns, but specific charters can also define additional local government authorities. For example, the Town of Front Royal has specific authority to charge payment in lieu of taxes (PILOT) fees to its water and sewer customers in Warren County.

The town extended water and sewer service outside the town boundaries in the 1990's. Town Council feared providing those utilities would undercut economic development initiatives, so Front Royal and Warren County negotiated a deal. Commercial utility customers located in the county pay an extra fee, comparable to the property taxes that would be paid if the buildings were located inside the town boundaries. The General Assembly passed a specific law to authorize the deal.

In 2017 the town planned to request revisions to the town's 1937 charter, in part to ensure that a future Town Council could not move local elections back from November to May when there is less voter interest. The charter had already been modified 11 times, most recently in 2002.

The town recognized that asking for change in town authorities created a risk. While revising the charter, the General Assembly could modify its approval of the PILOT program because it had not been authorized for all cities and towns.14

the Town of Front Royal is surrounded by Warren County

Source: Warren County, Timmons Group Web LoGIStics