Jamestown was the first port for ocean-going ships in Virginia

Source: National Park Service, "Jamestown - Sidney King Paintings," Arrival of Lord Delaware

Jamestown was the first port for ocean-going ships in Virginia

Source: National Park Service, "Jamestown - Sidney King Paintings," Arrival of Lord Delaware

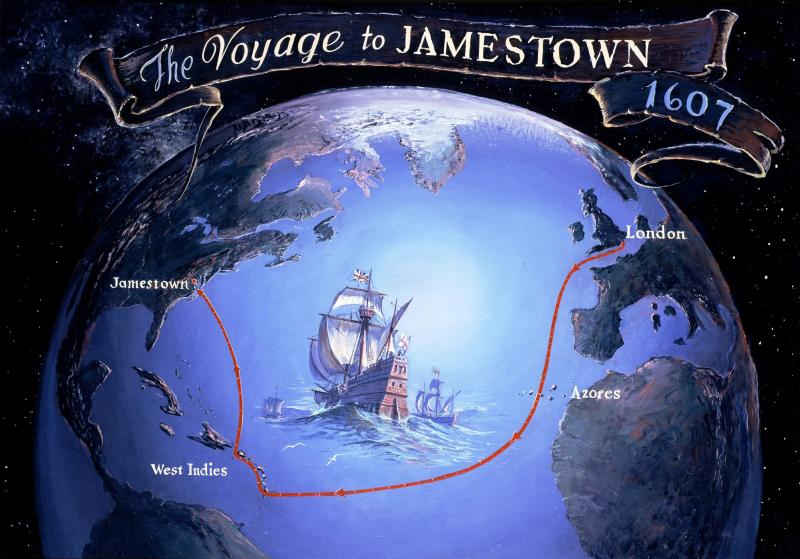

Ocean-going ships have stopped at Virginia wharves since the Spanish explored north from the Caribbean. The first English colonists arrived in 1607 and anchored at Jamestown, establishing the first port city. For the first century of colonization, it remained the only major port. Trans-Atlantic ships sailed to wharves dispersed throughout Tidewater, rather than stop to load/unload at just a few locations.

Early trade involved importing colonists and manufactured goods from England, including clothing, iron tools, and guns/ammunition. Virginia exported raw materials such as sassafras, deer hides, lumber, and especially tobacco to Europe.

Food became a major export item, once the colonists displaced the Native Americans and established farms. In the 1600's and 1700's, Virginia supplied much of the corn, wheat, and pork sent to the Caribbean. Planters there chose to dedicate most land and slave labor to growing sugar, and imported food rather than grew it.

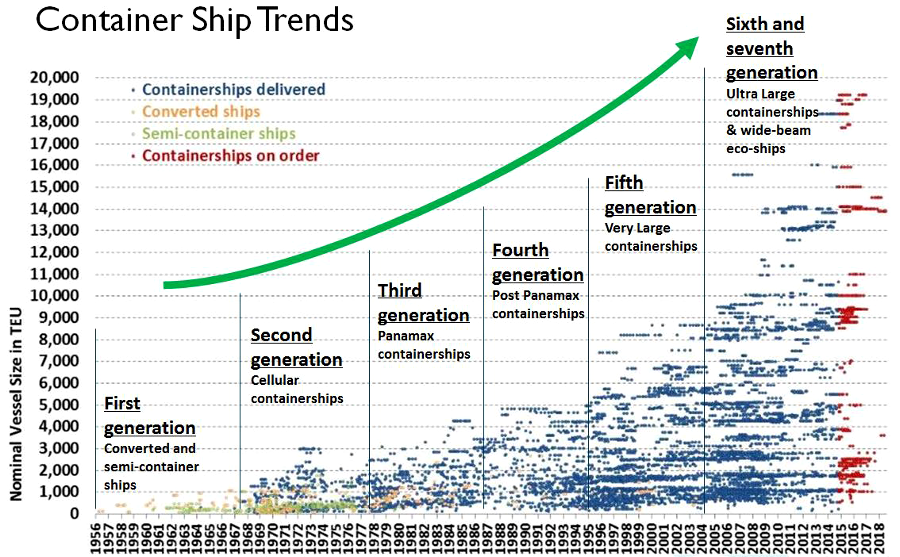

Virginia still exports raw materials, particularly coal and food. Most international trade today involves shipments not in crates, sacks, or hogsheads but in containers. They are measured in TEU's, for "twenty-foot equivalent units." Most containers are 40 feet long, and containers of that length are counted as two TEU's in port statistics.

Development of towns where wharves were concentrated to create a "port" occurred slowly in Virginia. There were few roads in the 1600's or even the 1700's that were passable when the ground was wet. It was not feasible to use carts pulled by oxen to carry hogsheads of tobacco, loads of lumber, or barrels of flour/salted beef very far on land. Plantation owners in Tidewater preferred to ship directly from their individual wharves, rather than carry goods overland and store them in warehouses at someone else's wharf until a ship arrived.

view from the river of replicas of the first English ships at Jamestown - Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery

The deep channels of multiple rivers and the colonial government's generous grants of land shaped the development of Virginia east of the Fall Line. The various rivers connecting to the Chesapeake Bay provided easy access for trans-Atlantic ships to collect cargo from many "necks" (peninsulas) and riverbank wharves in Tidewater.

the natural river channels of the Piankatank, Rappahannock, and other rivers in Tidewater were deep enough for ocean-going ships in the 1700's to sail directly to plantations, delaying the development of centralized port towns

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1755)

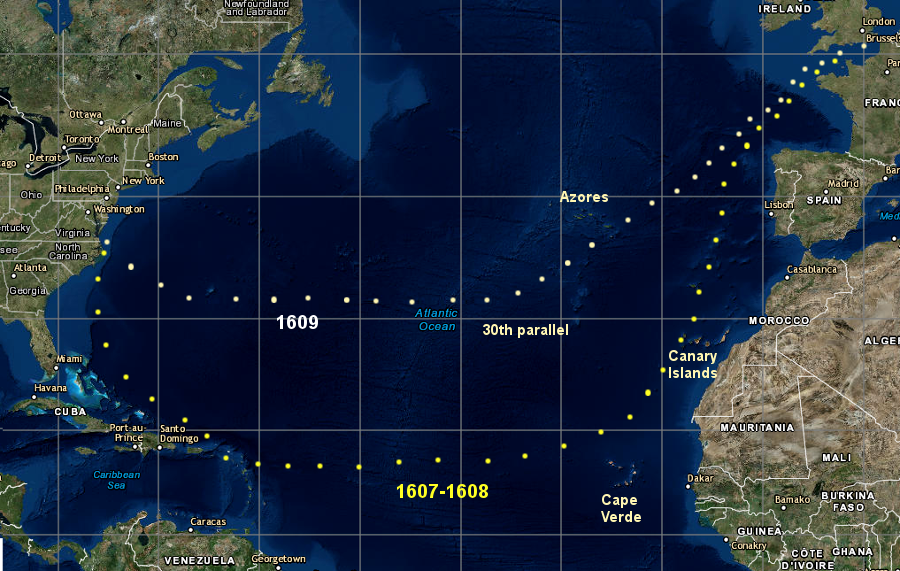

Initially, international trade with the Virginia colony required sailing from England south to the Canary Islands off the African coast, then turning west. Trade winds powered ships steadily across the Atlantic Ocean to the West Indies. On those islands ships could get fresh water and gather food, then turn north to sail 1,500 miles to Virginia. The trip could take up to 18 weeks, not counting delays in waiting for favorable winds to sail out of the English Channel.

the Virginia Company sent the first ships to Jamestown, and the first two resupply missions under Captain Newport in 1607 and 1608, via the Caribbean

Source: National Park Service, "Jamestown - Sidney King Paintings," Voyage to Jamestown

In 1609, the Virginia Company found a shortcut. Captain Samuel Argall was sent in advance of the nine ships in the Third Supply to sail south to just the Azores and then turn west, following the 30th parallel of latitude. That route cut at least three weeks off the trip, and avoided the risk of dealing with the Spanish who occupied much of the Caribbean.1

starting in 1609, the Virginia Company sent its ships via the 30th parallel, speeding up the trip and avoiding the Spanish in the Caribbean

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

After a ship arrived at a Virginia plantation, it would dock at a major plantation's wharf. It would then launch the ship's shallop (a small boat used in shallow waters), and together with local boats a ship would collect hogsheads of tobacco, wheat, lumber, and other products. Those items would be gathered from the separate wharfs of smaller, nearby plantations/farms. Almost every colonist could interact with international visitors; sailors from a wide variety of exotic locations were "in the neighborhood" almost annually.

The use of small boats to collect cargo from multiple locations on the river reduced the number of stops a ship had to make to gather a full load for the return to Europe. However, the inefficient collection process required a trans-Atlantic ship to spend as much as seven unprofitable months in Virginia to collect 300 hogsheads of tobacco.2

18-wheel trucks carry supplies on paved highways to retail outlets today, but during the 1600's the colonists lived near rivers and relied upon ships

Source: Architect of the Capitol, Washington's Farewell Address, 1796

The impact of Virginia's physical geography on the settlement pattern and international trade was clearly recognized by English officials, who desired concentrated development to facilitate military defense and the collection of taxes. As John Clayton noted in 1688:3

The result, as one recent scholar has noted:4

hogsheads of tobacco were shipped from Jamestown, but away from the colonial capital ships had to stop at multiple wharves built at separate plantations

Source: National Park Service, Jamestown Lifescape - Mid-17th Century (Keith Rocco painting)

In the 1700's, concentrations of population led to development of port towns. Yorktown emerged as the port servicing the new capital at Williamsburg after 1699, and Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Hampton developed in Hampton Roads.

Population expanded into the Piedmont, and agricultural products from west of the Fall Line were shipped down rivers. Deep channels in Tidewater allowed ocean-going ships to sail all the way inland to the Fall Line in the colonial era. By 1750, other ports had developed 60 miles west of the coast at Petersburg, Richmond, Newcastle, Fredericksburg, Dumfries, and Alexandria.

Because it offered a safe harbor on the Elizabeth River and was closest to Europe, Norfolk was Virginia's leading port at the time of the American Revolution. It had close ties to merchants in England, and was a Loyalist stronghold.

After Lord Dunmore fled Williamsburg in 1775, he had British warships anchor off Norfolk. After a series of incidents the British burned part of the town at the start of 1776, and the patriots completed that destruction so Norfolk would not serve as a British base during the war. The shipyard at Gosport and Hampton served as primary bases for the Virginia Navy during the American Revolution until the 1779 raid by Admiral Sir George Collier and General Edward Mathew, followed by invasions under General Alexander Leslie and then General Benedict Arnold in 1780.

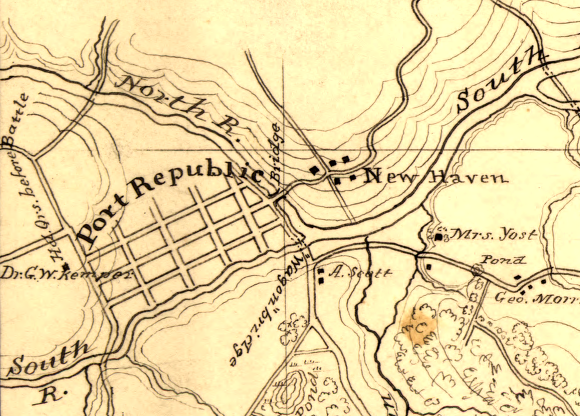

Port Republic, where the North, Middle, and South rivers merge to form the South Fork of the Shenandoah River, reflects Virginia's dependence on water-based transportation even far inland from ocean-going ports

Source: Library of Congress, Topographic map of the battle-field of Port Republic, Virginia, June 9, 1862

Norfolk rebuilt after the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, but as population increased to the west more trade came down Virginia's rivers and stopped at the Fall Line. Ports further west, closer to the inland trade than ports in Hampton Roads, gained more traffic.

New technology also reshaped shipping patterns. The new steamships developed after 1815 could push up the James River to the Fall Line fast while sailing ships that relied upon windpower had to tack back and forth across the river. By the 1820's, Richmond surpassed Norfolk as Virginia's largest port.

the Port of Richmond is 100 miles up the winding, shallow James River from Norfolk, much closer to farms on the Piedmont

Map Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

The state capital maintained its leadership position until after the Civil War. That dominance was extended in part because Richmond and Petersburg interfered with Norfolk's growth. The Fall Line cities used their influence to erect political and financial barriers that delayed Norfolk's efforts to build railroads that would connect Hampton Roads ports with the farmers exporting crops from the Piedmont of Virginia and North Carolina.

Between the Civil War and World War I, ocean-going ships grew larger and required deeper channels, and Norfolk surpassed Richmond. By the 1880's, the biggest ships required 19' deep channels. Richmond was able to get Congressional funding to cut direct routes through several bends in the James River, but the river channel was dredged to only 18' by 1916.

After the Civil War, exports were sent to deeper-water ports east of the Fall Line. The Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railroad bypassed Richmond in 1882, when Henry Huttleston Rogers built the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad down the Peninsula and created a new coal-shipping port at Newport News. The Norfolk and Western Railroad expanded its coal-shipping terminal at Norfolk, and the Virginian Railroad later built its terminal just to the north at Sewell's Point.

Large steamships brought imports to Norfolk, Portsmouth, or Newport News, then collected their next load of cargo there. Goods going inland to Richmond were transferred to smaller vessels in order to be "lightered" upstream. Whenever possible, shippers sent goods directly from deepwater ports in Hampton Roads. The extra costs to use an extra ship, to get cargo up or down the shallow James River channel, led to the decline of Richmond as a port city.

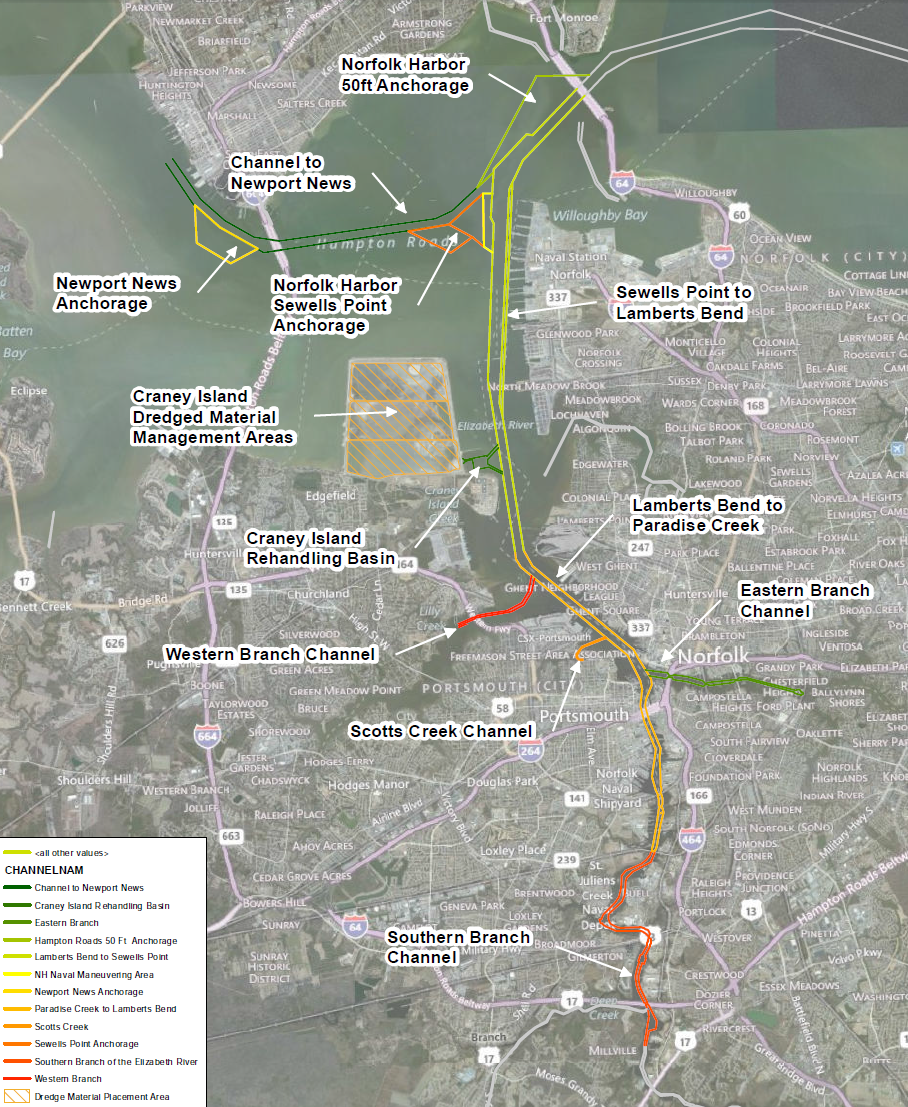

dredged channels at Hampton Roads

Source: National Marine Fisheries Service, Maintenance of Chesapeake Bay Entrance Channels and use of sand borrow areas for beach nourishment

During the Great Depression in the 1930's, the US Army Corps of Engineers dredged a 25' deep James River shipping channel. It was too little, too late; by then the bigger ships needed even more depth and a wider channel to maneuver. The Corps of Engineers still maintains a 300-foot wide, 25-foot deep channel to Hopewell and a 200-foot wide, 25-foot deep channel to Richmond, but shipping traffic is limited primarily to a barge service known as the 64 Express.5

the Pocahontas Parkway bridge over the James River has a high clearance, to allow ships to reach Deepwater Terminal just upstream

Source: US Federal Highway Administration, Introduction to Public-Private Partnerships (P3s)

As shipping to Richmond declined, traffic at ports in Hampton Roads grew. The railroads continued to use their private coal-exporting terminals at Norfolk and Newport News. Other companies built additional private terminals to import/export petroleum products, grain, and other commodities.

After World War II, the cities of Newport News, Portsmouth, and Norfolk each built a municipally-owned shipping terminal using local tax revenues and profits from terminal operations.

The Norfolk Industrial Port Authority was created by the city in 1948 to "bring the world to Norfolk, and bring Norfolk to the world." It expanded the US Army's original World War I Norfolk Army Base, which later had been used as the World War II Port of Embarkation and Korean War Hampton Roads Army Terminal. The city's Norfolk Tidewater Terminals competed with other municipally-owned terminals in Portsmouth and Newport News, as well as with privately-owned terminals in Hampton Roads.6

The Peninsula Ports Authority of Virginia owned the Newport News Marine Terminal on the northern bank of the James River. It contracted with the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railroad to operate the terminals until the early 1980's. Nissan chose Newport News as a primary entry site for its East Coast car imports, and that site competed with Baltimore to be the "roll on, roll off" hub in the Chesapeake region.7

The Portsmouth Port and Industrial Commission developed the Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT) at Pinners Point. The Western Branch Railway had built a terminal there in 1886, and in 1896 the Atlantic Coast Line and Southern Railway had greatly expanded the terminal there.8

Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT)

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk Harbor Navigation Improvements - Draft General Reevaluation Report and Environmental Assessment (Figure 2-4)

After World War II, population growth led to fierce competition among Hampton Roads jurisdictions with territorial annexations, consolidations, and conversion of counties to city status, particularly to limit Norfolk's expansion. The competition between local governments limited the state's efforts to market the strengths of three different ports as a single package, in order to generate regional and statewide growth.

The General Assembly had created the Virginia State Ports Authority in 1952, hoping to create more shipping-related jobs in Virginia. However, the three jurisdictions resisted guidance from the state. Each city wanted a return on their local investment for their local taxpayers, and sought to increase its local market share.

Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Newport News competed more than cooperated with each other. The rivalry and fragmentation undercut efforts by the Virginia State Ports Authority to attract new shipping. The refusal of the separate jurisdictions in Hampton Roads to consolidate their municipal governments also limited bonding capacity and other revenue that could be used to expand the capacity of the separate terminals.9

the Virginia Port Authority acquired three municipally-owned ports in 1971-72, and the consolidation of operations and investments to upgrade equipment led to a dramatic increase in containerized cargo over the next 40 years

Source: Virginia Coastal Energy Research Consortium, Hampton Roads Maritime And Ports Capacity Report (July 2009)

In the 1960's, the container revolution required expensive investment in new cranes and redesign of land-based facilities. The local jurisdictions finally determined that the costs of port expansion would be too high.

At the same time, the General Assembly determined that it would not provided state funding for port expansions unless the state had a stronger role in managing the assets. The Virginia State Ports Authority was renamed the Virginia Port Authority and, with the support of the three cities, the state agency acquired the three municipal terminals.

The Virginia Port Authority took ownership of the Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT) and the Newport News Marine Terminal (NNMT) in 1971. It acquired the Norfolk International Terminal (NIT) in 1972. In 1989, the state agency opened the Virginia Inland Port (VIP) in Warren County. That allowed shippers who used a Virginia terminal in Hampton Roads to send cargo to/from a site west of the Blue Ridge with less cost or hassle.

In 2010, the Virginia Port Authority leased the privately-owned A. P. Moller Terminal (APM) in Portsmouth and renamed it the Virginia International Gateway (VIG). In 2011, the state agency leased Deepwater Terminal from the City of Richmond and renamed it the Richmond Marine Terminal (RMT). The Virginia Port Authority has also ensured its future dominance by planning for construction of a new terminal on Craney Island, whenever demand justifies expansion of capacity to handle more containers.10

The Virginia Port Authority now advertises a consolidated Port of Virginia, describing the various terminals controlled by the Virginia Port Authority. The Virginia Port Authority essentially has a monopoly on shipping terminals within Virginia that process containers.

containerized shipping has transformed Virginia's terminals since the 1960's

Source: Port of Virginia, 2016 Annual Report (p.13)

There is still private competition for some cargo; the state does not have a complete monopoly on all shipping terminals in Virginia or even in Hampton Roads. The Virginia Port Authority does not own or lease the coal-exporting terminals used by the CSX and Norfolk Southern railroads, or the small terminals on the Elizabeth River used to import/export petrochemicals, grain, or other "break bulk" cargo transported by a large container ship. Wharves at small ports in Tidewater, from Chincoteague to Alexandria, are not part of the Virginia Port Authority.

The 1970's consolidation under the Virginia Port Authority was intended to streamline operations among the publicly-owned terminals and with the longshoremen, shipping companies, and railroads. Greater efficiency was intended to draw business away from competing East Coast ports, particularly in New York/New Jersey, Baltimore, Charleston, and Savannah, in order to spur growth both near the ports and far inland throughout Virginia:11

container ships have expanded in size, creating new requirements for greater channel widths and depths

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Purpose and Need for USACE Action

There are economies of scale in shipping. Coal export costs are lower per ton when ships are larger, and the same formula applies to container ships. In colonial days, the natural depth and width of shipping channels made Hampton Roads an attractive location for ports. Today, dredging is required to accommodate the large ships of the US Navy and commercial business.

Between 1989-2007, the US Army Corps of Engineers excavated 50-foot deep channels and anchorages for traffic inbound and outbound to the terminals on the Elizabeth River at Newport News. Funding constraints delayed further deepening to 55-deep channels.

After the expansion of the Panama Canal in 2016 enabled wider and deeper container ships to go from Asia to the East Coast, the Corps proposed even wider and deeper channels. There was no guarantee that the US Congress would appropriate the necessary funding to implement those recommendations. The Virginia Port Authority and the US Army Corps of Engineers negotiated a cost share agreement in 2015 to study deepening the channel, and that led to funding the project.

In 2019 excavation began to deepen the western side of the Thimble Shoal Channel to 55 feet, with the rest of the dredging to that depth to be completed over the next five years. In 2024 the Corps started work on Atlantic Ocean Channel Phase II, dredging the ocean approach to 59 feet. Norfolk ended up as the port on the Atlantic Ocean on the United States with the deepest shipping channel.

The US Army Corps of Engineers said:12

One justification for channel expansion is the military presence in Hampton Roads.

Newport News Shipbuilding, the only shipyard designing/building US Navy aircraft carriers and one of two designing/building nuclear submarines, is located on the James River at Newport News. The Norfolk Naval Shipyard, where some Navy vessels are maintained and repaired, is on the South Branch of the Elizabeth River. When it was first started in 1767, it was called the Gosport Shipyard, then the Gosport Navy Yard, U.S. Navy Yard Norfolk, and Norfolk Navy Yard Portsmouth. In 1945 the military designated the facility as "Norfolk Naval Shipyard."

the Norfolk Navy Yard - in Portsmouth, not Norfolk - was destroyed by Federal forces in 1861 and then by Confederate forces evacuating in 1862

Source: Library of Congress, Ruins of the navy yard at Norfolk, Va., December 1864

The names and locations of military facilities in the region can be confusing. Naval Station Norfolk (also called the "Norfolk Navy Base"), where ships are stationed between tours, is located in Norfolk, Virginia. The separate Norfolk Naval Shipyard, where ships are repaired, is within the municipal boundaries of the city of Portsmouth, Virginia. There is a Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, but it is located in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.13

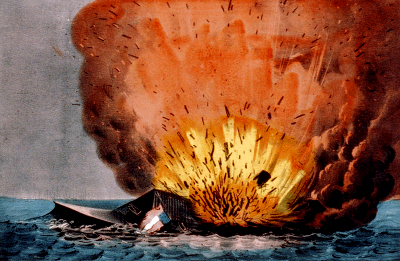

The Norfolk Naval Shipyard played a key role in the Civil War. In April 1861, Virginia military forces seized the shipyard even before voters ratified the Ordinance of Secession. At the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, the Confederate Navy converted the USS Merrimack into the armored CSS Virginia. The Confederate ironclad ship then engaged the USS Monitor in the "Battle of Ironclads" on March 9, 1862.

When shipyard workers added armor plating to cover the wooden deck of the old USS Merrimack, they also increased the weight of the CSS Virginia so it would ride low in the water and protect the unarmored hull. As a result, the CSS Virginia was unable to flee when the Confederates abandoned Norfolk in May, 1862. The ironclad required a 22-foot deep channel but the natural channel up the James River to the Confederate capital of Richmond was shallower, so the Confederate warship was scuttled at burned at Craney Island.14

the Confederate Navy destroyed the CSS Virginia in 1862 when Norfolk was abandoned, because the ironclad required a channel deeper than 18' to steam up the James River to Richmond

Source: 1862 Currier & Ives lithograph from National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Service (NOAA), Monitor National Marine Sanctuary

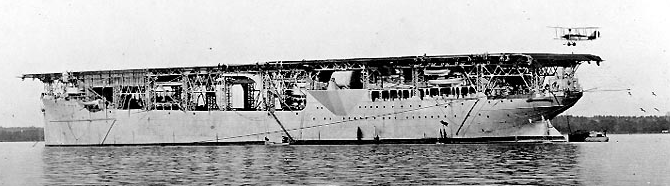

1922 airplane landing on USS Langley, the Navy's first aircraft carrier (built at Norfolk Naval Shipyard)

Source: 1862 Currier & Ives lithograph from National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Service (NOAA), Monitor National Marine Sanctuary

Building ironclads was not the end of innovation at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard. After World War I, the coal-carrying USS Jupiter was converted there into the USS Langley, the first US aircraft carrier.

Today, all aircraft carriers are built at a shipyard in Newport News, and the five nuclear-powered aircraft carriers in the US Navy Atlantic Fleet are "homeported" at Naval Station Norfolk. The US Navy advertises that facility as "the largest naval complex in the world."15

There is no guarantee that the carriers will be based only at Naval Station Norfolk. After the last conventionally-fueled carrier was retired, the Pentagon considered transferring one aircraft carrier from Norfolk to the retired carrier's homeport, Naval Station Mayport (near Jacksonville, Florida).

Upgrading Mayport to deal with nuclear-powered ships would cost $500 million-$1 billion, but would enhance continuity of operations by reducing dependency upon just one facility. In 2012, Virginia politicians foreclosed the potential loss of jobs/economic activity in Hampton Roads by blocking appropriations in Congress for any transfer.16

aircraft carriers docked at the Norfolk Naval Base are readily visible to people driving across the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel to Willoughby Spit (in background)

Source: CNIC Naval Station Norfolk, Welcome to Naval Station Norfolk

When the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel was constructed across the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay in 1994, Virginia adopted a design that accommodated the Navy. The military was concerned that any bridge across the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay could become a barrier to ship traffic, if an enemy (in 1964, that meant the Soviet Union, Cuba or "Red" China) managed to destroy the bridge and it ended up blocking the shipping channel.

To ensure that could never happen, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel was constructed as a hybrid. A standard bridge crosses most of the distance between Virginia Beach-Northampton County, but tunnels were dug below the Trimble Shoals and Chesapeake shipping channels. For the same reason, transportation infrastructure crossing the James River below Newport News and the Elizabeth River below the Norfolk Naval Shipyard include tunnels, to ensure shipping channels remain open.17

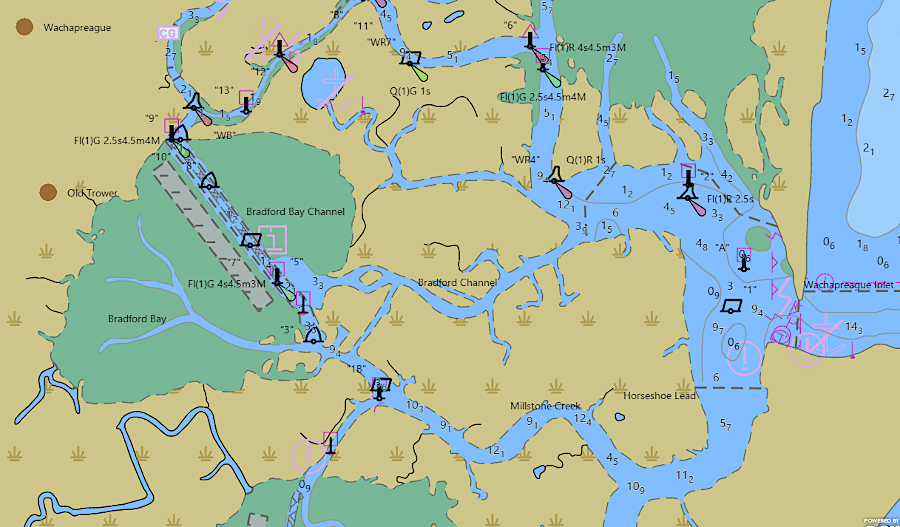

a dredged channel enables boats to get through the barrier islands east of Wachapreague

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), NOAA ENC Viewer and ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The military presence is generating a new generation of high-tech businesses, in addition to providing payrolls and contracts for normal operations. The Army as well as the Navy provides economic drivers for Virginia's ports.

The US military's primary center for logistics education is located now at Fort Lee (near Petersburg). That site grew in importance after a Base Realignment and Closure Commission decision to move the headquarters of the U.S. Army Transportation center and equivalent units to Fort Lee. Local and state economic development seek to convert military-funded research in logistics and simulation/modeling into new civilian-oriented businesses in Hampton Roads.

The state created the Commonwealth Center for Advanced Logistics Systems in 2013 to build on military contractor expertise, and to link manufacturing companies (such as Rolls-Royce's advanced manufacturing facility for jet engines in Prince George County, Virginia) and universities (starting with University of Virginia, Longwood University, Virginia Commonwealth University and Virginia State University).18

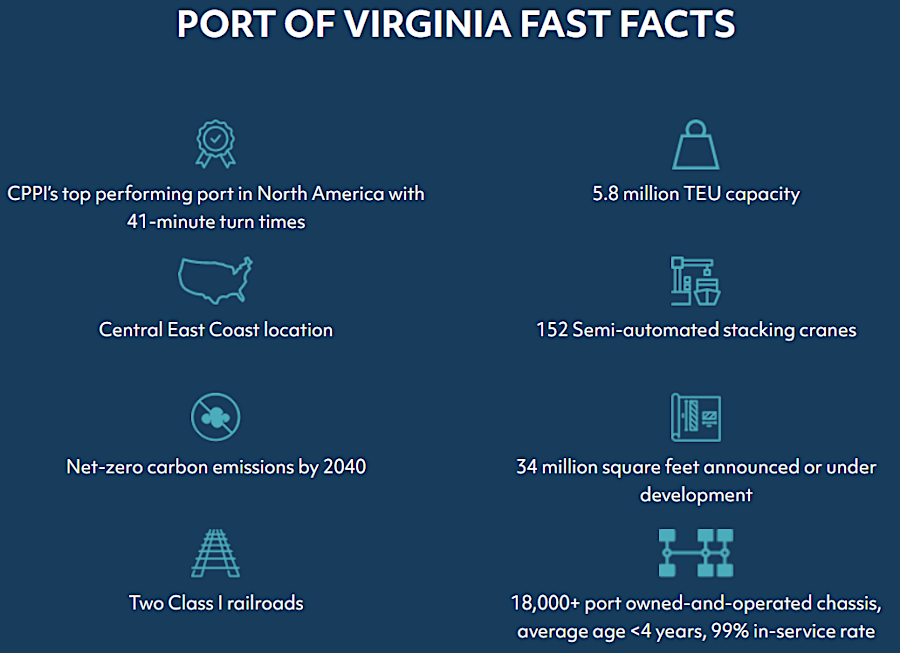

To take full advantage of the competitive advantage of the deepest and widest shipping channel on the East Coast, the Port of Virginia launched the Gateway Investment Program in 2023. At Norfolk International Terminal (NIT), new ship-to-shore cranes were installed. Semi-automated technology was incorporated in modernizing the North Terminal there.

The container stack yard was reconfigured and the central rail yard was expanded by almost one-third so the Norfolk International Terminal (NIT) could process 1.8 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) by rail annually. Further expansion was planned to increase the capacity to 3.6 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs).

Combined, all Port of Virginia terminals processed 3.5 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) in 2024. By 2027, the port planned to have the capacity to process 5.8 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) annually.19

The Port of Virginia seeks to increase traffic by making grants to companies who will ship through one of the Hampton Roads terminals, even if the businesses are located far inland. In 2019, it awarded a $500,000 Economic and Infrastructure Development Grant to incentivize Morgan Olson to establish a plant in Pittsylvania County that would manufacture box trucks used by package delivery companies. The grant terms required to the company to have at least 574 workers at the facility for three years.

Morgan Olson announced permanent layoffs in 2023 and 2024 due to "current economic conditions and forecasts." Employment dropped below the threshold required by the grant. In response, the Virginia Port Authority demanded the company return the $500,000. The company completely repaid the grant on November 20, 2024.20

Expansion of capacity led to an increase of port revenues by over 50% between 2020-2024. However, traffic was projected to be affected after President Trump launched a trade war with new tariffs in 2025. Europe was the largest source of shipping at the Port of Virginia, but China was #2 with 19%.

Half of the exports leaving Hampton Roads by ship were agricultural exports. China responded to the initial 145% tariff by cutting orders for American farm products, but private companies still chose to invest in expanding containerized agricultural export facilities near Portsmouth.

The port's Chief Executive Officer noted that West Coast ports would be most impacted by the 2025 tariffs; 45% of Los Angeles shipping was with China. In his opinion:21

Expansion of the Norfolk International Terminal (NIT) continued into 2026. It added four new, Suez-class ship-to-shore container cranes (bringing the total to 29 deepwater ship-to-shore cranes) and a fourth ultra-large vessel berth.

Investment in that terminal and deepening the channel to service ultra-large container vessels (ULCV's) would be completed when a fifth ultra-large vessel berth was added in 2027. The Executive Director of the Virginia Port Authority announced in February, 2026:22

the Port of Virginia invested to increase capacity so it could process 5.8 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) annually by 2027

Source: Port of Virginia, Gateway Investment Program, The Most Modern Gateway in America

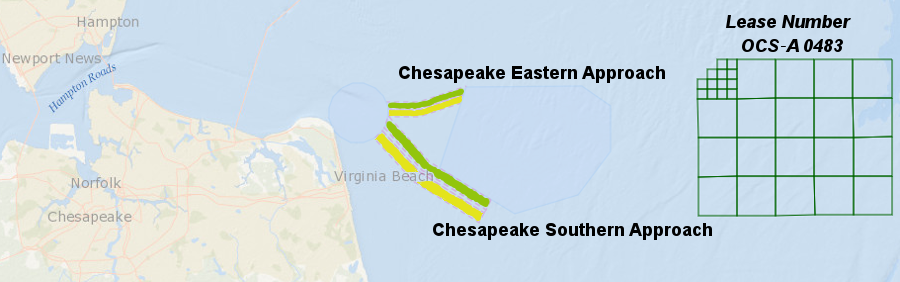

blocks leased by the Federal government for offshore wind turbines are located away from the designated inbound (green) and outbound (yellow) shipping channels

Source: Bureau of Ocean and Energy Management, Exploring Ocean Wind Energy