the Virginia Port Authority owns and leases terminals from Hampton Roads to the Shenandoah Valley

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Review of the Virginia Port Authority's Competitiveness, Funding, and Governance (2013)

the Virginia Port Authority owns and leases terminals from Hampton Roads to the Shenandoah Valley

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Review of the Virginia Port Authority's Competitiveness, Funding, and Governance (2013)

The Virginia Port Authority is a public agency, managed by a board that the governor appoints. The agency is not required by law to make a profit, or even to balance expenditures with revenues each year. Investors can not buy stock in the state agency or replace management through shareholder votes.

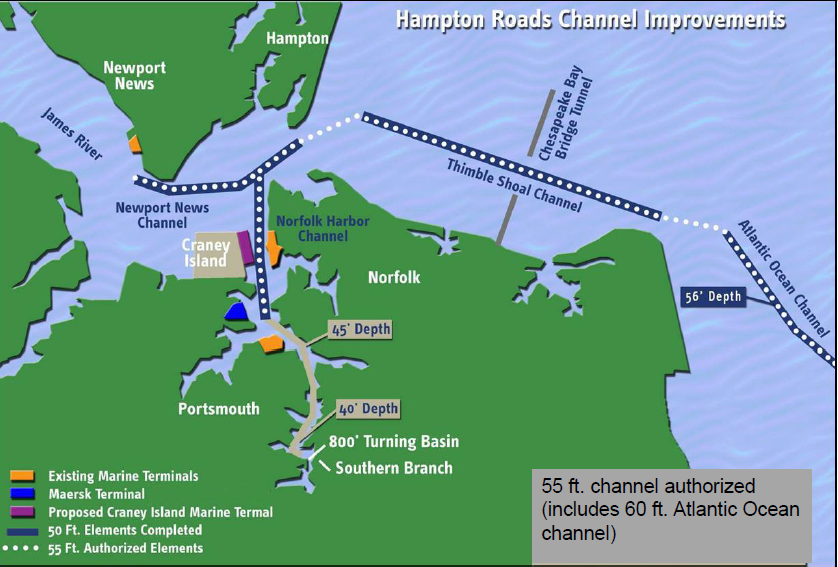

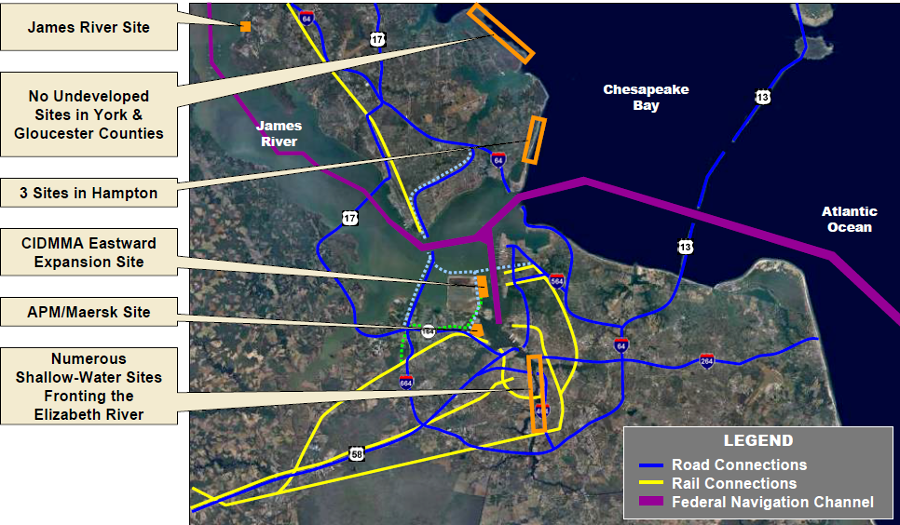

The Virginia Port Authority owns three major terminals in Hampton Roads plus the "inland port" in the Shenandoah Valley. It also has long-term leases on the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) terminal in Hampton Roads (originally known as the A. P. Moeller or APM terminal) and the Richmond Marine Terminal (RMT). In anticipation of increased demand for containerized shipping, the Virginia Port Authority has plans to build a new terminal on Craney Island in four stages, with the first stage opening in 2040.

In addition to containers, the Virginia Port Authority terminals provide shippers a place to load/unload a wide range of non-containerized cargo. "Roll-on, Roll-off" (Ro-Ro) cargo ranges from cars to wind turbine blades. The major private shipping terminals focus on bulk products such as soybeans, petroleum, and coal shipments.

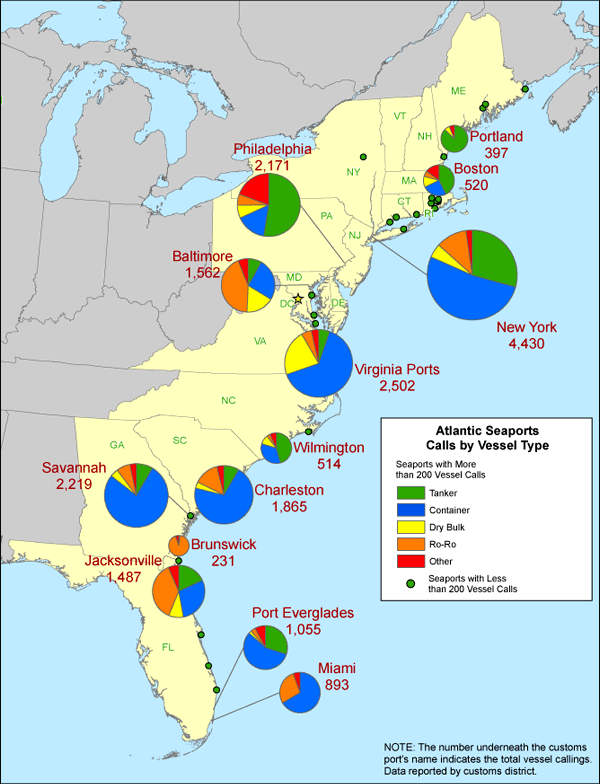

types of ships that called at Atlantic ports, 2009 ("Ro-Ro" stands for "roll-on, roll-off" ships carrying cargo such as Nissan cars to Newport News)

Source: Bureau of Transportation Statistics, Atlantic Coast U.S. Seaports (Figure 3)

In addition to owning/leasing the land and infrastructure at the Virginia Port Authority terminals, the state of Virginia also operates all but one of them through Virginia International Terminals, Inc. (VIT). The one exception is Richmond. The Virginia Port Authority retained the existing private operator when it leased Deepwater Terminal from the city.

Since the 1950's, shipping at Virginia's publicly-owned ports has shifted from break-bulk cargo (shipped on pallets) to standardized containers (moved by cranes directly to trucks/rail cars). Operations are far more efficient, after massive investments of capital to modernize cranes, upgrade rail/truck access, and enhance information technology. Containerization has dramatically reduced the need for workers, but the unionized members of the International Longshoremen's Association are essential for port operations.

Virginia is a right-to-work state, and the General Assembly prohibits union negotiations by state agencies. In shipping, it is not possible to bypass the International Longshoremen's Association, Teamsters, and other unions, so the state legislature chartered the Virginia International Terminals (VIT) in 1983.

at the Port of Virginia terminals designed for containerized cargo, specialized equipment picks up containers from trucks

Source: Virginia Maritime Association, Full Potential

VIT is a non-stock corporation wholly owned by the Virginia Port Authority, but technically it is a private company. As the operator of state-owned terminals, VIT could negotiate labor contracts without violating the state legislature's long-standing restrictions on dealing with unions.

Virginia politicians traditionally have objected to government intervention in the private sector. Having the state government control the ports, a key sector of the economy, appears out of synch with the political culture of the state. Even more surprising, a Republican governor rejected proposals to privatize the ports in 2012, and instead consolidate state operations to increase efficiency.

State control of shipping terminals is relatively recent, dating from the 1970's. There was a public wharf at Jamestown starting in 1607, but that became irrelevant in 1699 when the colonial capital was moved from Jamestown to Williamsburg. Yorktown became the new port for the colonial capital, and private citizens or municipal governments built and operated wharves and docks in Virginia.

Starting in 1813 state government was deeply involved in financing roads, canals, and railroads through the Board of Public Works until the Civil War. However, the state left the responsibility and cost of building and operating waterfront facilities, where cargo was loaded/unloaded onto ships, to the private sector or to local governments.

The Federal government funded lighthouses and dredged shipping channels, but did not finance port infrastructure in Virginia except at military bases.

Traffic to Hampton Roads ports increased after the Civil War. The number of ships going upstream to Richmond, Petersburg, Fredericksburg, and Alexandria declined after the 1870's as the size of ships increased. Larger ships required deeper channels than those available in the James or Rappahannock rivers, and the time required to get the larger ships to Alexandria was too expensive. It was more cost-effective to load/unload at Hampton Roads ports, allowing the big ships make more trips in the Atlantic Ocean than in Virginia's rivers.

After World War II, the cities of Portsmouth, Norfolk, and Newport News developed publicly-owned terminals. At the time, most cargoes still involved "break bulk" goods packed on various sorts of pallets and in sacks, plus bulk cargo such as loose grain, lumber, petroleum, and coal.

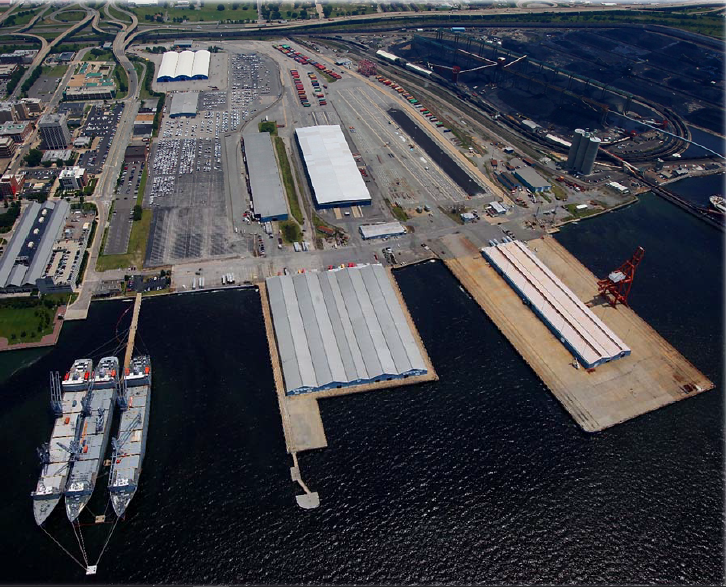

Newport News Marine Terminal (NNMT)

Source: Virginia Office of Intermodal Planning and Investment, Master Rail Plan for the Port of Virginia (Figure 18)

In the late 1950's, the US Army Corps of Engineers supported commercial shipping by building a dredge spoils facility at Craney Island. The Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area permanently stores the muck dredged out of the channels in the James River, Nansemond River, Elizabeth River, and Chesapeake Bay.

The adoption of containerized shipping in the 1960's required expensive upgrades to ports so they could provide cranes, chassis storage yards, and truck/railroad connections. Fierce competition among the Hampton Roads ports limited potential economies of scale, and undercut efforts by the state to increase trade to any destination in Virginia.

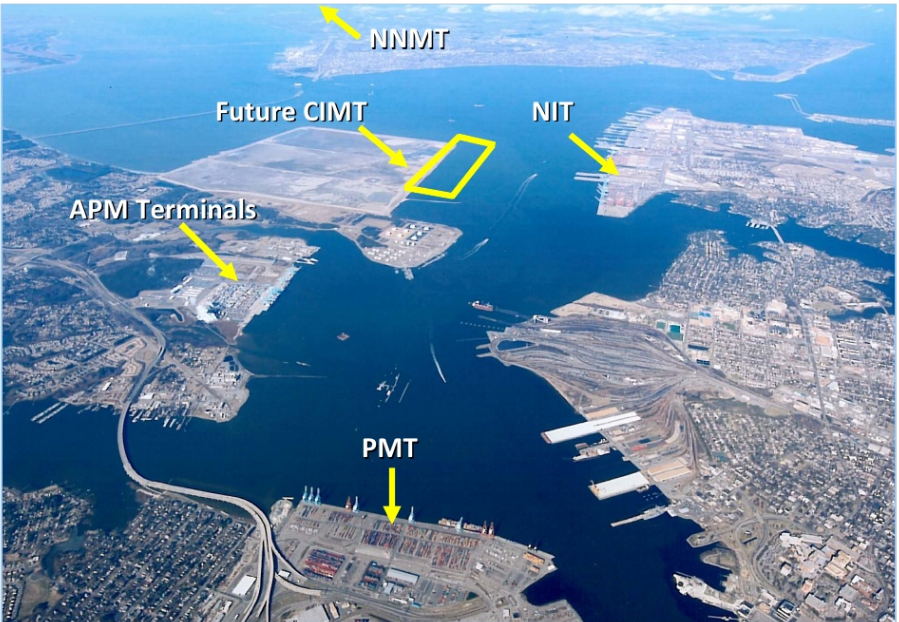

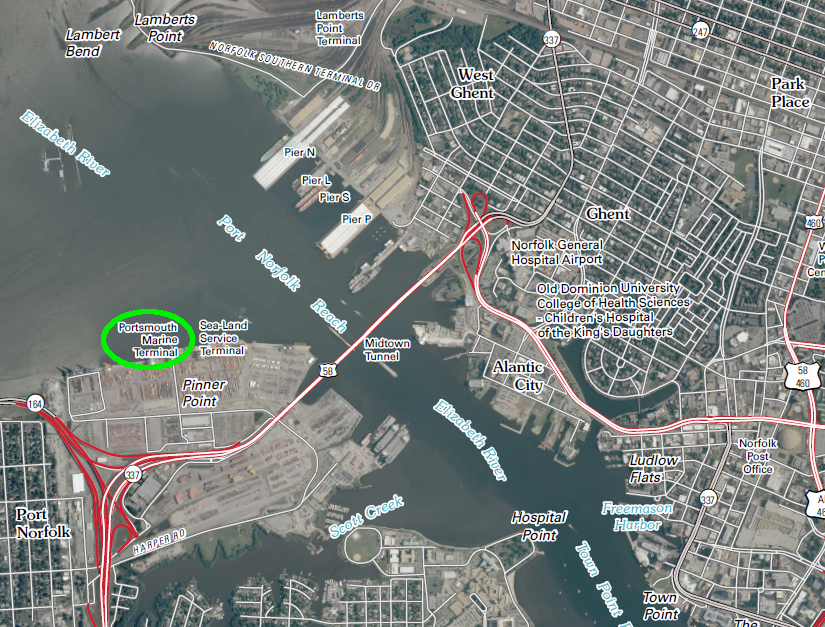

Rather than borrow money to buy equipment and reconfigure their terminals to handle the increasing number of containers, the Hampton Roads cities transferred their facilities to the state. The Virginia Port Authority acquired the Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT), Newport News Marine Terminal (NNMT), and Norfolk International Terminal (NIT) in 1971 and 1972.

terminals in Hampton Roads include Newport News Marine Terminal (NNMT), Norfolk International Terminals (NIT), Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT), APM/Maersk Terminal (APM) - now Virginia International Gateway (VIG), and the future Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) (the privately-owned coal terminal at Lamberts Point, used by Norfolk Southern railroad to load coal, is visible between PMT and NIT on the east side of the Elizabeth River)

Source: Port of Virginia, State of the Port (2009)

The state built the Virginia Inland Port (VIP) in Warren County in 1989. Streamlining transport of cargo from a "port" located west of the Blue Ridge to the Chesapeake Bay helped to attract traffic away from rival ports such as Baltimore. It also reduced traffic congestion on highways and air pollution. A 75-car freight train can carry 150 containers, at far less cost than 150 trucks, the 200 miles between Front Royal and Hampton Roads.

In 2006, the US Army Corps of Engineers completed a Feasibility Study that determined the Virginia Port Authority would run out of container processing capacity in Hampton Roads in 2011. The study also projected that the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area would be filled in 2025.

In response, the Virginia Port Authority and the US Army Corps of Engineers committed to expand the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area and build the new Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) on top of that expansion. The new terminal would double the capacity to process containerized cargo delivered by truck, rail, or barge to Hampton Roads for export, or arriving on a ocean-going container ship from Asia and Europe.

two dikes on eastern side of Craney Island will be connected by a third perpendicular dike to create a 200-acre cell, to be filled with dredge spoils and then developed as a new terminal by 2028

Source: Virginia Port Authority/Corps of Engineers, Containment Dikes Break Surface of the Elizabeth River

The private sector saw the capacity constraints as an opportunity. The A. P. Moller-Maersk Group, a Danish business conglomerate which owned the Maersk shipping line, built a new container processing terminal in 2007. The A. P. Moller (APM) terminal was constructed just north (downriver) of the state-owned Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT).

The private company operated the A. P. Moller (APM) terminal for only three years. The state negotiated a 20-year lease in 2010, later extended to 2065. Today the facility is known as the Virginia International Gateway (VIG).

In 2011, the Virginia Port Authority signed a 40-year lease with the City of Richmond to operate the Richmond Marine Terminal (RMT), which had been known as Deepwater Terminal since it opened in 1940.

Through acquisitions and leases since 1971, the Virginia Port Authority has become the dominant force with control over all major containerized cargo shipping terminals in Virginia.

Consolidating the containerized cargo terminals under the Virginia Port Authority has increased efficiency and improved marketing to attract more ships to Virginia's ports. In 1980, the Hampton Roads ports ranked #30 in the United States (measured by tons of cargo handled). By 2013, the ports had risen in rank to #3.

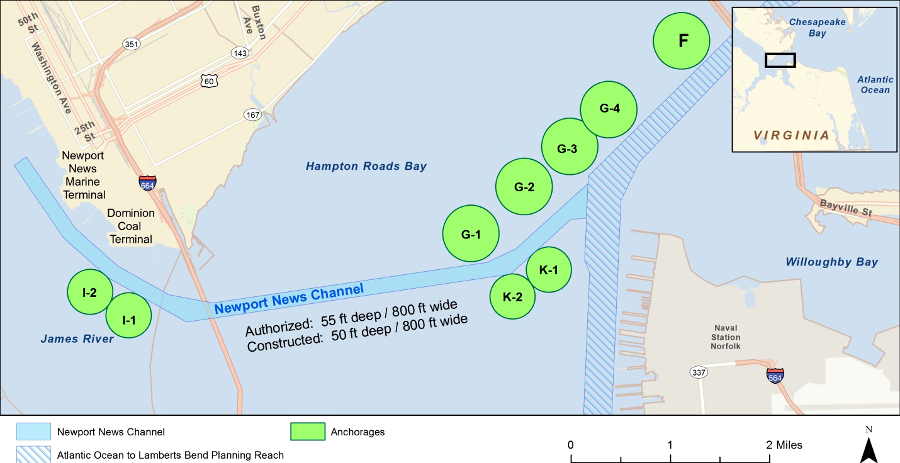

That growth was facilitated by the 50-foot deep shipping channels dredged by the UA Army Corps of Engineers. Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Newport News can handle the largest ships that carry containers today.1

the US Army Corps of Engineers has dredged a 50-foot deep shipping channel to Newport News and Norfolk terminals, plus deep anchorages for ships

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk Harbor Navigation Improvements - Draft General Reevaluation Report and Environmental Assessment (Figure 1-3)

After the state gained control over the terminals in Hampton Roads in the 1970's, it invested heavily to increase their capacity. In the first 40 years of state ownership, the General Assembly spent $1 billion to upgrade port infrastructure. The funding covered the annual costs of operating the terminals in years when they failed to make a profit, plus the state's share of costs for dredging, infrastructure improvements, and planning the future Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT).

In 1986, Governor Baliles and the General Assembly raised taxes significantly to finance transportation projects. The transportation tax package included dedicating funding to the new Commonwealth Port Fund to pay for port-related infrastructure improvements.

Between 1986 and 2012, that dedicated funding provided nearly $700 million for expanding capacity. The General Assembly has appropriated an additional $300 million from the General Fund.2

Today the Virginia Port Authority handles almost all of the containers shipped into or exported from Virginia, as well as much of the "break bulk" cargo and "roll-on roll-off" cargo such as cars. The network of state-controlled facilities is called the "Port of Virginia," though at times that term is used loosely to include privately-owned terminals in Hampton Roads.

Two privately-owned terminals at Newport News (Kinder Morgan and Dominion Terminal Associates) export "steam" and "metallurgical" coal delivered by the CSX railroad. The Norfolk Southern railroad has its own massive coal export terminal (Pier 6) in Norfolk. If there was sufficient demand, Pier 6 could ship 48 million tons of coal per year.3

Other privately-owned terminals on the Elizabeth River handle shipments of grain, wood products, petroleum, and other non-containerized cargo. Throughout the Chesapeake Bay and along the Atlantic Ocean side of the Eastern Shore, small communities have private and public wharves that handle local shipping, including seafood-related products.

Richmond Marine Terminal (RMT) at the Port of Richmond (POR)

Map Source: Virginia Office of Intermodal Planning and Investment, Master Rail Plan for the Port of Virginia (Figure 27)

The 2006 Feasibility Study projected that demand for processing containerized cargo would exceed the capacity of the state-owned terminals, especially after 2015 when the expansion of the Panama Canal was supposed to open. In anticipation of the arrival of Ultra-Large Container Vessels (ULCV's) carrying up to 14,000 TEU's in Hampton Roads, the state and US Army Corps of Engineers made plans to build a new Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT).

Virginia and the Corps of Engineers agreed to expand the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area, north of the private APM terminal that was built in 2007. New cells would be added on the east side, and the new terminal would be constructed on top of the new cells.

Sand from the Dam Neck Ocean Disposal Site would be used to build containment dikes for the cells. The interior of the new cells would be filled with the clay-rich sediments that were dredged regularly from the bottom of the Elizabeth River and Hampton Roads, in order to deepen/maintain shipping channels.

Expanding the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area gave the US Army Corps of Engineers extra capacity for disposal of dredge spoils, at a location close to the shipping channels and anchorages being dredged. Building new cells for storage would be expensive, but would also be cost effective compared to alternative disposal sites.

The expansion would delay when the day when Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area was filled up. Once it reached capacity, dredge spoils would have to be transported to the distant Norfolk Ocean Disposal Site in the Atlantic Ocean. Barging the dredge spoils that extra distance would increase significantly the Corps' costs for maintaining the depth of the Hampton Roads shipping channels.

costs to transport dredge spoils to the Norfolk Ocean Disposal Site far exceed disposal at the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Ocean Disposal Map

The extension of the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area into the Elizabeth River was designed to create new land. The Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) would be constructed in stages on top of completed cells, after sediments in the cells had compacted sufficiently.

The future pile-supported wharf built on the new fill could support up to 28 container cranes, which can process 2.5 million "twenty-foot equivalent units" (TEU's) at full capacity. That would double the capacity to process containers at the Norfolk International Terminals (NIT) and Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT). Once the Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) was fully built, the state-owned terminals could handle five million TEU's per year.

The plans to expand the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area and build a new terminal there were visionary. Construction costs were estimated at over $2 billion. Creating the new terminal was a long-term project that required decades to plan, and would require even more decades to implement.

The Craney Island Eastward Expansion Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) was approved in 2006. Final permits to expand the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area, by the addition of new dredge spoil, were issued by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality in 2010. Construction of the first cells began soon afterwards.4

terminals in Hampton Roads where ships load/unload containerized and break bulk cargo

Source: The Port of Virginia Infrastructure Update - Norfolk (February 16, 2012)

Hampton Roads has been an international shipping destination since 1607

Source: Commonwealth of Virginia, Statewide Rail Plan (Figure 2-6)

In 2009, at the direction of the General Assembly, the state considered selling its shipping terminals. That would have abolished the Virginia Port Authority, or converted it into some form of a public-private partnership.

The board of the state agency rejected privatization proposals in 2009 and again in 2012. It decided instead to expand.

Even before the privatization debate, Virginia International Terminals (the operating arm of the Virginia Port Authority) discounted its standard fees charged to shippers. After A. P. Moller-Maersk opened its private terminal in 2007 and sent Maersk ships there, those discounts had helped state-owned terminals keep most the business of competing shipping lines.

Discounts pumped up the number of containers as the privatization choices were considered. The increased business made the port appear to be a better investment for the state. However, the discounts were so great that the terminals had to pay overtime to move the extra containers. Costs were also high because many containers were being handled at the outdated and inefficient Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT). Despite increased container traffic, costs far exceeded revenue, and a state official noted:5

The Virginia Port Authority's decision to lease the privately-owned A. P. Moller (APM) terminal in 2010 gave the state a new, efficient container-processing terminal. From the state's view, leasing the A. P. Moller (APM) terminal eliminated the only serious competitor for processing containerized cargo in Hampton Roads. Monopoly control ensured the Virginia Port Authority could direct ships to whichever terminal it desired, so efficiency would be maximized.

The Virginia Port Authority decided to lease, rather than buy, the A. P. Moller (APM) terminal. That allowed the state to minimize its initial costs, but required spending more money over the next 20 years. In the middle of the economic recession, borrowing $450 million to purchase the facility would have been controversial. Keeping costs low in the short-term was more important than minimizing overall costs throughout the 20-year lease.

After leasing the A. P. Moller (APM) terminal, the Virginia Port Authority shifted container traffic to it from the Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT). A portion of the now-unneeded space at Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT) was leased to a company exporting wood pellets. At the 287-acre site, 50 acres were provided to the contractors building the new Midtown Tunnel between Portsmouth-Norfolk.

The Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT) ended up dormant, but it was not "mothballed." In 2014 it was used to ship 2,500 Chrysler Jeep SUVs to China. In 2014, as an unexpected surge number of shipping containers created congestion at the Norfolk International Terminals (NIT) and Virginia International Gateway (VIG) terminals, the Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT) was re-activated as a container terminal.

The lease for the wood pellet export operation was terminated in 2015. With completion of the Midtown Tunnel in 2017, the Virginia Port Authority regained full control over the site and invested in upgrades to increase capacity from 80,000 TEU's/year to 200,000 TEU's/year.6

Soon after the significance of the COVID-19 pandemic became clear, container imports dropped and the Virginia Port Authority had excess capacity. All containers were diverted away from the 287-acre Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT). At that site, 40 acres of unneeded space were leased to Orsted for assembly of turbines for Dominion Energy's offshore wind farm. Dominion leased another 72 acres in 2021.

constructing the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project required transporting materials offshore from a shipping terminal in Hampton Roads

Source: Dominion Energy, Timeline

In 2021, in an effort to rebuild traffic at the terminal, the Virginia Port Authority signed a contract with the U.S. Transportation Command in the Department of Defense. Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT) was targeted as a new facility for shipping military cargo.

The 597th Transportation Brigade, based at Joint Base Langley-Eustis, had previously trained stevedores at the terminal on how to move tanks, helicopters, and large items of military equipment. Though the 2021 contract was only for $15 million in services over five years, port officials anticipated that its military shipping business could grow. The headline for the story about the deal in The Virginian-Pilot was:7

Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT)

Source: Virginia Office of Intermodal Planning and Investment, Master Rail Plan for the Port of Virginia (Figure 8)

Also in 2021, Dominion Energy chose two European firms, Orsted and Siemens Gamesa, to help develop its Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project. Orsted leased 40 acres at Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT), Siemens Gamesa leased over 80 acres to finish blades for 100 turbines a year, and Dominion leased another 72 acres to assemble towers and foundations for the 180 wind turbines. Dominion ordered construction of a specialized American-registered ship, which the company named Charybdis, to carry equipment from the terminal in Portsmouth to the site of Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind in the Atlantic Ocean.

materials for 176 wind turbines were staged at Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT) before installation at the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project

Source: Dominion Energy, Project Background

State and regional officials hoped that more companies would choose to manufacture and service turbines in Hampton Roads. The first location on the Atlantic Ocean coastline to achieve a critical mass of expertise and wind energy providers could make Portsmouth into the equivalent of Detroit for automobiles. When announcing in October 2021 the decision of Siemens Gamesa to complete wind turbine blades at the terminal, Governor Northam proclaimed:8

However, in 2023 Orsted cancelled its participation in two offshore wind projects in new Jersey. That decision cost the company $4 billion. Soon afterwards, Siemens Gamesa cancelled its plans to build blades for offshore wind turbines at the Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT).9

Portsmouth Marine Terminal is constructed in part on material dredged from the Elizabeth River when the Midtown Terminal was built in 1962

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Norfolk South 7.5 minute topographic quad (2011)

alternative locations considered for a new container terminal, before selecting eastward extension of Craney Island

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Craney Island Eastward Expansion Feasibility Study (slide 18)

The Virginia Port Authority lost money in its annual operations between 2008-14. The state agency revised contracts and operational procedures to reduce overtime and other costs, and finally returned to profitability in 2015.

Leasing the A. P. Moller (APM) terminal allowed the Virginia Port Authority to push back the completion date for the new Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT). Funding could be used to install new cranes to handle containers faster at the existing terminals.

However, a 20-year lease of the A. P. Moller (APM) terminal was not long enough to justify upgrading that facility. Purchasing new infrastructure to increase capacity at the terminal would not be cost-effective, because the lease would expire before the end of the useful life of the new equipment.

The new governor, elected in 2013, already viewed the A. P. Moller (APM) terminal lease as a poor business deal. Gov. Terry McAuliffe began negotiating with the private owners to extend the 20-year lease.

Gov. McAuliffe, like his predecessor Gov. McDonnell, used his appointment authority to ensure that his negotiations would be supported by the Virginia Port Authority, and that his priorities would be implemented. He replaced five of the eleven members on the agency's board.

One option considered by the governor was to default on the lease of the A. P. Moller (APM) terminal. However, the contract signed under Governor McDonnell committed the state to pay APM. Gov. McAuliffe described that contract as "one of the worst lease deals I've ever seen negotiated."10

If Virginia built a new terminal on Craney Island and then broke its lease, the private owners of the A. P. Moller (APM) terminal would end up competing against the state for shipping contracts. That possibility incentivized A. P. Moller-Maersk Group to sell its terminal in 2014 to a different group of private investors.

The sale ended concerns that the Maersk shipping line might (or might not) receive special consideration once the lease expired. The new owners renamed the terminal as the Virginia International Gateway (VIG).11

the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) Transfer Zone provides space for containers to be moved by a straddle carrier onto a truck chassis

Source: Virginia International Gateway, Terminal Cameras

During lease negotiations, the state also considered purchasing the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) outright, but in 2016 the Virginia Port Authority and the new owners signed a revised lease. It added an extra 35 years to the lease, extending it from 2030 to 2065.

The 35-year extension was key to upgrading capacity. The state was unwilling to invest in new equipment at the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) terminal when the amortization period was just 15 years, but the lease extension gave the state control for 50 years. That justified spending money to upgrade the cranes and other infrastructure.12

Once again, Virginia officials arranged terms so the initial, up-front costs would be minimized. In the extended lease, the private owners agreed to finance the cost of expanding new equipment, doubling capacity to about 2.2 million TEU's annually.

The state did not pay the $320 million upgrade costs at Virginia International Gateway (VIG). Instead, the private owners borrowed the funds and the state agreed to increase its annual payment to reimburse the private investors. The new contract committed the state to pay $4.2 billion total, and gave Virginia the right to purchase the terminal in 2065 at fair-market value.

In 2024, the City Council in Portsmouth feared that the Port of Virginia would make a new proposal to purchase the Virginia International Gateway (VIG). State rather than private ownership would make the facility exempt from local property taxes. Nearly 40% of the land in Portsmouth was already tax exempt. If the city lost the $9 million/year from the terminal, then City Council would have to raise taxes by $0.09/$100 to replace the lost revenue.13

When completed in 2019, the terminal was 800 feet longer and able to load/unload three ultra-large container ships at the same time. Virginia International Gateway (VIG) ended up with 56 rail-mounted gantry cranes moving containers at 28 container stacks. Truckers were required to book reservations 24 hours in advance, so the "turn time" to load containers from the stack onto a truck could be reduced to below one hour. Truckers who did not use the reservation system could not get onto the terminal until after 2:00pm.

At a ceremony for the completion of the terminal expansion, Governor Ralph Northam commented:14

The new lease of the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) created concerns in the City of Portsmouth. The terminal's equipment was private property. City taxes on it generated $7.5 million per year; the terminal was the largest taxpayer in Portsmouth.

The deal shifted $64 million worth of assets to the Virginia Port Authority. New cranes would speed container processing, but the City of Portsmouth would not be able to tax the state-owned equipment.

To replace the lost taxes paid by Virginia International Gateway (VIG), the City Council estimated it would have to raise property taxes by 4%. Such an increase would be a substantial percentage for the jurisdiction that already had the highest tax rate in Hampton Roads, and where over half the property (including the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, the Naval Medical Center, and Craney Island) was tax-exempt.15

To offset the lost local tax revenue, the General Assembly agreed to a $5.1 million interest-free loan for Portsmouth. Repayment was anticipated to occur after expansion at the port, which would result in higher revenue to Portsmouth.

After Portsmouth assessed the real estate and personal property value of Virginia International Gateway (VIG) and raised the tax base of the facility from $361 million to $770 million, the private owners appealed and said it was worth $197 million. Portsmouth wanted to increase the 2015-16 real estate bill from about $4.7 million to $10 million, while the private owners proposed lowering the tax bill to $2.6 million.

After a nine-day trial, a state judge decided that neither the private owners of the terminal nor the city had proven their numbers were correct. The Virginia International Gateway (VIG) expert was not licensed in Virginia as an appraiser when he testified, so the judge excluded his testimony. The judge found the city's appraiser was not qualified to make the assessment, and discarded his estimate of value as well. The judge let the city's appraised value stand because:16

In 2017, the General Assembly also altered the authority of the governor to replace the members on the Virginia Port Authority board at any time. The legislature passed legislation that established fixed terms for those appointed to the state agency's board. Appointees will now serve five-year terms, and may be re-appointed for one additional term. Board members are no longer serving "at the pleasure of the governor," however, and are no longer at risk of being fired without cause.17

After arranging a lease that expanded capacity at the Virginia International Gateway (VIG), the General Assembly approved $350 million in new bonds to upgrade the Norfolk International Terminals (NIT). The investment, including 26 new gantry cranes at Virginia International Gateway (VIG) and 60 at Norfolk International Terminals (NIT), was planned to increase the number of containers that terminal could process by nearly 50%, from 1.4 million TEU's annually to over 2 million TEU's.18

the General Assembly approved $350 million in 2016 to increase capacity at the Norfolk International Terminals (NIT) by almost 50%

Source: Port of Virginia, 2016 Annual Report (p.12)

Increasing capacity at the existing Virginia International Gateway (VIG) and Norfolk International Terminal (NIT) allowed the Virginia Port Authority to meet projected demand beyond 2030. The investment of $320 million to expand Virginia International Gateway (VIG) and the long-term lease of that site until 2065, plus the $350 million upgrade at the Norfolk International Terminal (NIT), reduced the need to complete the Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) by 2028 as originally scheduled. Current planning is to open its first component in 2040.19

if built, the Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) would be on the west side of the Elizabeth River, opposite the two piers at the Norfolk International Terminals (NIT)

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk Harbor Navigation Improvements - Draft General Reevaluation Report and Environmental Assessment (Figure 3-2)

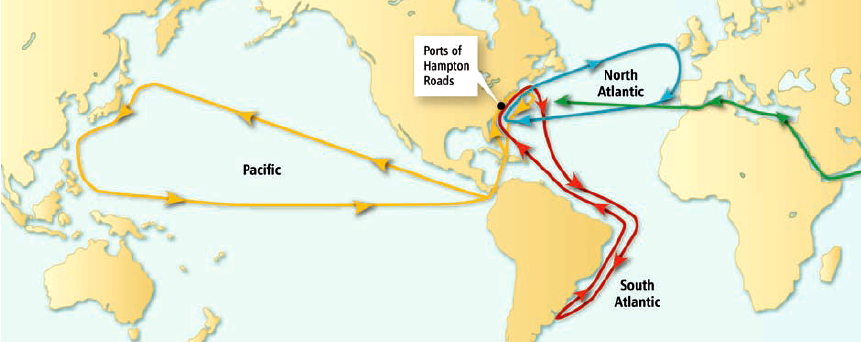

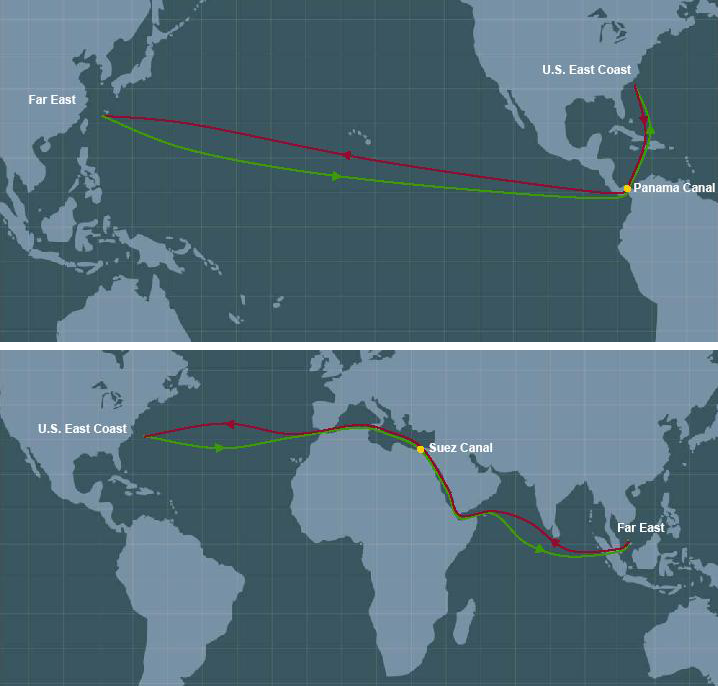

Shippers bring cargo from Asia implemented a dual-gateway strategy to reduce reliance on West Coast ports by expanding service through the Panama Canal to carry containers to East Coast ports. Since 2000, East Coast ports have doubled their share of Asian imports to 30%, despite the extra week or so required to sail the extra distance.

most ships from the Far East get to East Coast ports via the Panama Canal or the Suez Canal

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Savannah Harbor Expansion Project - Final General Reevaluation Report (Figure 5-1, Figure 5-2)

The first "neo-Panamax" ship arrived at Norfolk International Terminals (NIT) in July, 2016, after stopping first at the Global Terminal in Bayonne, New Jersey. It inaugurated a new shipping route linking the Asian ports of Qingdao, Ningbo, Shanghai, and Busan with New York, Norfolk and Savannah.20

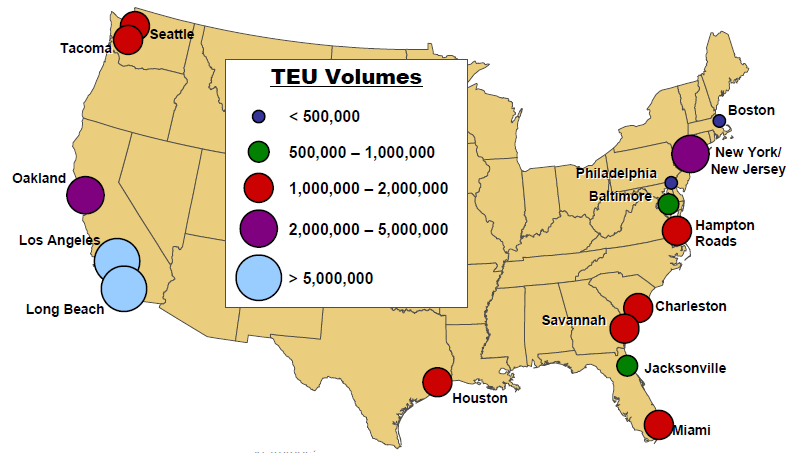

ports in Virginia, New York/New Jersey, South Carolina, and Georgia expanded capacity in anticipation of attracting more business, after widening of the Panama Canal in 2016 allowed ships with 10,000 TEU's to reach the East Coast

Source: Supply Chain 24/7, The New Expanded Panama Canal: Bigger Ships, Bigger Paydays for Beans, Coal, and Gas (June 26, 2016)

The Portsmouth Marine Terminal was repurposed in 2020 to become the maritime support center for offshore wind facilities, starting with Dominion Energy's Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project. Land at the terminal was leased to Orsted, Siemens Gamesa, and Dominion Energy, so the companies could assemble the turbines to be installed in - port officials hoped - multiple offshore projects.

the six blue gantry cranes at Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT) were removed in 2022, as the site was converted from cargo operations to support of offshore wind projects

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Cargo operations were shifted to Virginia International Gateway and Norfolk International Terminal. As part of the shift in use, the six blue gantry cranes which had extracted containers and other cargo from ships were removed. Three were sold for installation in the Dominican Republic, and the other three were sold for parts.21

Portsmouth officials remained concerned that the Port of Virginia would purchase the Virginia International Gateway (VIG), converting private property that paid taxes to the city into state property that would be tax-exempt. The 2025 General Assembly approved amendments to the state budget that would allow the Virginia Port Authority to set a price now for purchasing the terminal when the lease expired in 2065.

In 2024, 40% of the land within Portsmouth's boundaries was not taxable by the city due to state or Federal ownership. Virginia International Gateway paid $9 million annually in property taxes, and replacing that revenue would require increasing the city's tax rate by $0.09. To ameliorate the concerns of Portsmouth officials, Virginia Port Authority committed to have advance communications so discussions involving a purchase would be transparent and the city could propose how to avoid a loss in tax revenue.22

A major investment in the terminals and shipping channels at Hampton Roads was nearing completing in 2025. The shipping channels from the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay to the terminals on the Elizabeth River were dredged to 55 feet in depth, a project that cost $450 million. The extra depth allowed container ships carrying as many as 20,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) to arrive or depart fully loaded.

The Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT) was transformed to support offshore wind projects, starting with the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project built by Dominion Energy. Additional offshore projects were halted when the second Trump Administration eliminated offshore leasing in Federal waters, but that terminal was well positioned for a future change in policy.

The Norfolk International Terminal (NIT) was upgraded in a $650 million expansion to include 33 ship-to-shore cranes. The container stack yard and rail network were enhanced to process an additional additional 1.4 million TEUs, raising capacity to 3.6 million TEUs. Combined, the investment of $1.4 billion expanded the various Virginia Port Authority terminals so they could process 5.8 million TEUs per year.23

major container ports with Twenty Foot Equivalent Units (TEU's)

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Craney Island Eastward Expansion Feasibility Study (slide 19)

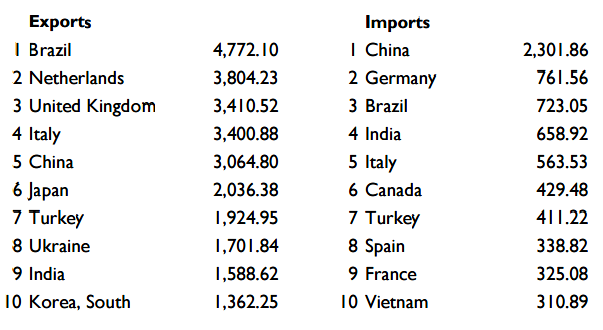

the top 10 trading partners in 2015 for the Port of Virginia (measured in Thousands of Short Tons) were different for imports and exports

Source: Port of Virginia, 2015 Trade Overview

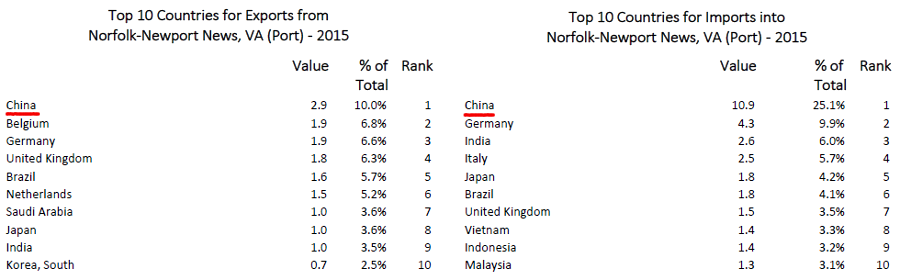

the value of cargo exported and imported at Newport News from China was balanced in 2015

Source: Bureau of Census, USA Trade Online

wind turbines at Portsmouth Marine Terminal, ready for installation at Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project

Source: Dominion Energy, Monthly Mariner's Update - Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind (CVOW) (February 1, 2026)