indentured servants and slaves were the first port workers, loading hogsheads of tobacco at colonial Virginia wharves

Source: National Park Service, Sidney King Paintings Gallery - A Shipping Scene

indentured servants and slaves were the first port workers, loading hogsheads of tobacco at colonial Virginia wharves

Source: National Park Service, Sidney King Paintings Gallery - A Shipping Scene

The workers at the docks who load/unload shipping containers and other cargo are known as "longshoremen," though they may also be described as stevedores, dockworkers, crane operators, hands, lashers, casuals, etc. and may not be "men" anymore. On the East Coast, unionized longshoremen belong to the International Longshoremen's Association.

Successful labor relations are essential to maintaining business activity at Virginia's ports and across the world. There are six locals of the International Longshoremen's Association representing workers at Hampton Roads ports, ILA Locals 846, 970, 1248, 1624, 1736, and 1970.

The Hampton Roads Shipping Association (HRSA) represents the employers who negotiate with the union. The Virginia Maritime Association is a separate business lobby group that advocates for government support of the ports, and is not involved directly in labor negotiations.

At the Federal level, the responsibilities to promote and regulate shipping were combined under the Federal Maritime Board until they were split in 1961. The United States Maritime Administration within the U.S. Department of Transportation promotes waterborne transportation. The Federal Maritime Commission is an independent regulatory agency, and it regulates shipping contracts to address unfair and deceptive practices in the industry.

Workers in different East Coast ports united their negotiation efforts in 1916, as World War I altered Atlantic Ocean trade and Congress passed the Shipping Act of 1916.

Until the East Coast longshoremen united in 1916, during a strike at one port the shipping companies could redirect their cargoes to a different port and break the strike. Once a worker's strike ended, normal deliveries could be resumed. That option was foreclosed once workers united under the International Longshoremen's Association and it started negotiating a "master contract" for all ports from Maine to Texas.

Until the Great Depression, port workers on the West Coast belonged to various unions, including the Industrial Workers of the World ("Wobblies") and the International Seamen's Union. A strike in 1937 failed, and workers then consolidated under the International Longshore and Warehouse Union. Today, shipping companies sending cargo to any East Coast/Gulf Coast port must negotiate with the International Longshoremen's Association, while for West Coast ports contracts are negotiated with the separate International Longshore and Warehouse Union.

supplies sent by the military to Europe in World War II and to Korea in the 1950's were loaded and unloaded from ships using nets

Source: US Army Transportation Museum, DUKW Amphibious 2-1/2 ton

Major container carriers, terminal operators and port associations for Gulf Coast and East Coast ports have organized into one group, the United States Maritime Alliance.

On the East Coast, the United States Maritime Alliance negotiates directly with the International Longshoremen's Association, the AFL-CIO union that represent longshoremen regarding wages, hours, benefits, and employment guarantees. Roughly every five years, workers at Virginia ports who belong to the International Longshoremen's Association vote to approve or reject the latest master contract negotiated with the United States Maritime Alliance. The union and the Port of Virginia, a state agency, also negotiate a local contract with specific local provisions.

On the West Coast, shippers have organized as the Pacific Maritime Association. That group is separate from the United States Maritime Alliance on the East/Gulf coasts, though some international shipping companies belong to both groups. The Pacific Maritime Association negotiates a separate master contract with the separate International Longshore and Warehouse Union.

The East/Gulf Coast and West Coast master contracts expire at different times; a strike by one union or a lockout by management will affect ports on just one side of the continent or the other. The two unions do not orchestrate simultaneous nationwide strikes, so shipping companies could redirect ships to ports on the other coast during a strike. The time and costs to go to the other coast may be expensive, but many factories now rely upon "just in time" deliveries and supply chain logistics may justify the cost.1

Ports on opposite coasts compete with each other on cost, distance required for inland transport, and on service. In 2002, West Coast ports were closed for 10 days while the Pacific Maritime Association and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union negotiated a new master contract. The expensive disruption of the supply chain caused Asian shippers to diversify their operations, expanding service through the Panama Canal to carry containers to East Coast ports and reducing reliance on West Coast ports.

Since 2000, East Coast ports have doubled their share of Asian imports to 30% despite the extra week or so required to sail the extra distance. Widening of the Panama Canal in 2016 has increased further the potential for East Coast ports to attract container ships that traditionally unloaded at West Coast ports.2

Since the 1950's, shipping at Virginia's publicly-owned ports has shifted from break-bulk cargo (moved on pallets or in sacks of various sorts) to standardized 40-foot long containers moved by cranes to trucks/rail cars.

A 2006 economic analysis of the terminals managed by the Virginia Port Authority documented that 88% of imports arrived in containers. Only 12% was roll-on roll-off (RoRo) bulk cargo such as cars. By 2013, 98% of the tonnage processed at the state-owned Port of Virginia terminals was containerized. The remaining 2% of "break bulk cargo" moved primarily through the Newport News Marine Terminal (NNMT), particularly imported automobiles.

Both the 2006 and 2013 reports indicated that 40% of goods imported via those Hampton Roads terminals remained in Virginia for sale to consumers, or for processing by Virginia businesses. Cargo in containers was easy to load directly on rail cars and trucks, and 60% of imported cargo was carried to out-of-state destinations by truck or rail.3

Moving containerized cargo is far more efficient, reducing the need for longshoremen. Mechanization has required massive investments of capital to purchase and then modernize cranes, build and then upgrade rail/truck access, and develop and then enhance information technology to synchronize the timing for ship arrivals with the availability of truck chassis, longshoremen, and space in storage yards.

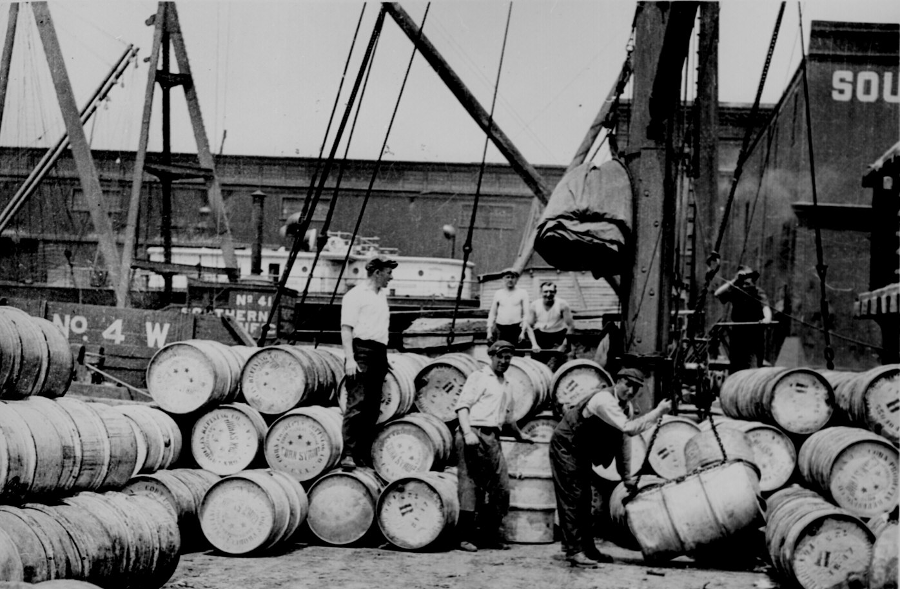

more longshoremen were required to load/unload cargo in individual barrels vs. 40' containers moved by gantry cranes

Source: National Archives, Stevedores on a New York dock loading barrels of corn syrup onto a barge on the Hudson River

Containerization has dramatically reduced the need for longshoremen, triggering demands to ensure a continued union role and to mitigate job losses due to automation. Shipping terminals in Hampton Roads and Richmond were once businesses based on labor and funded by wages. Now they are businesses based on equipment and funded by investment capital.

Edward L. Brown, president of the International Longshoremen’s Association in Hampton Roads, reflected in 2004 on changes in shipping since he started on the docks in 1956:4

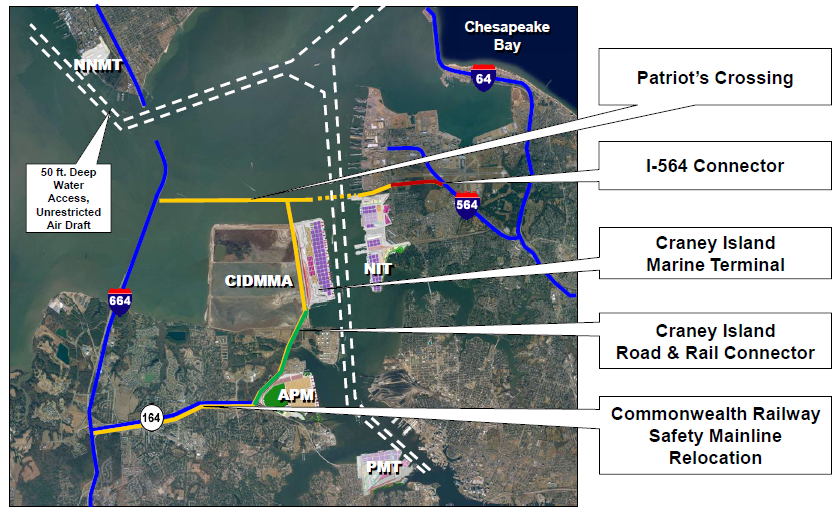

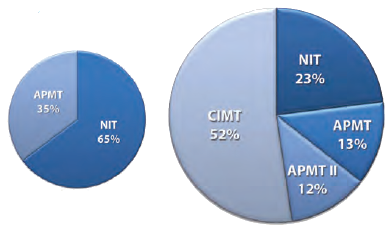

most containers in Hampton Roads are processed at terminals owned or leased by the Virginia Port Authority, and private terminals focus on break-bulk cargo such as grain and coal

Source: Virginia Port Authority, Special Report: Review of Recent Reports on the Virginia Port Authority’s Operations

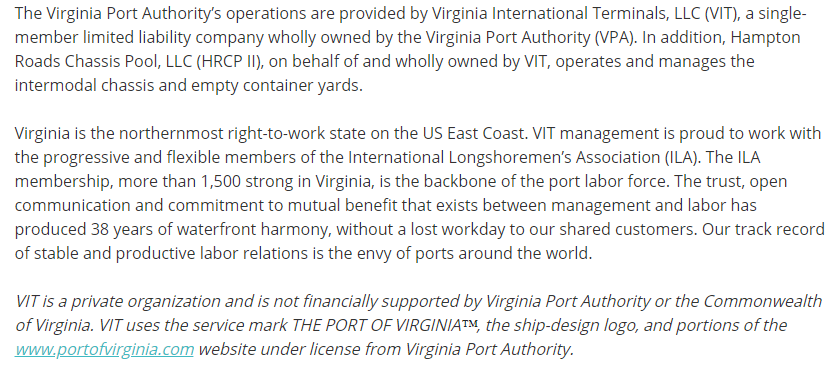

Virginia is a right-to-work state with a long history of support for management and opposition to labor, and the General Assembly has prohibited state agencies from negotiating with unions. To bypass that constraint on crafting labor agreements, the Port of Virginia (a state agency) hires service companies to manage operations, including union negotiations. Those companies can negotiate with the International Longshoreman's Association without violating the General Assembly's prohibition. Private terminals operated by Perdue, Kinder-Morgan, Norfolk Southern, and other companies negotiate directly with the International Longshoreman's Association.

The Port of Richmond has contracted with PCI (a private company), and it negotiates labor agreements for Richmond's port operations. When the Port of Virginia took over responsibility for the Port of Richmond, it changed how business was conducted and renamed "Deepwater Terminal" to "Richmond Marine Terminal" (RMT), but retained the services of PCI.

The Virginia Port Authority contracts with Virginia International Terminals (VIT) to operate the Hampton Roads terminals in Newport News, Portsmouth, and Norfolk, plus the Virginia Inland Port in Warren County. VIT is a non-stock, non-profit, tax-exempt independent corporation created by the General Assembly in 1983. VIT is wholly owned by the Virginia Port Authority, but technically VIT is not a state agency so it can engage in union contract negotiations. In 1985, the Virginia Attorney General ruled VIT was:5

technically, Virginia International Terminals (VIT) is a private corporation but it is 100% owned by a state agency, the Virginia Port Authority

Source: Port of Virginia, About

VIT's labor negotiations can affect the competitive position of its ports vs. New York/New Jersey, Charleston, Savannah, and other competitors. In 2013, after 13 months, the United States Maritime Alliance and the International Longshoremen’s Association agreed to another "master agreement" for East Coast and Gulf Coast ports. Most ports reached agreement at the same time with local unions for local contracts on work rules, but VIT negotiations with the International Longshoremen’s Association regarding 1,650 dockworkers at Norfolk required extended bargaining.

The key sticking point involved a requirement that VIT pay for three nonworking union members per crane, which had been included in the previous local contract on work rules. That provision minimized unemployment after new technology streamlined the loading/unloading of vessels docked at Norfolk International Terminals, but the cost made Norfolk less competitive with other East Coast ports.6

moving containers fast is the key to efficient operations at Virginia Port Authority terminals in Hampton Roads

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers (YouTube channel), District, Port Authority Agree on Craney

VIT became ensnared in a highly-political proposal to privatize Virginia' ports. It did not emerge as a winner.

Control of the ports became a political issue starting in 2008, when the Virginia General Assembly passed House Joint Resolution 72. It established a joint subcommittee to study public-private partnerships regarding seaports in Virginia.

State officials considered the option of selling its Hampton Roads terminals at Portsmouth, Newport News, and Norfolk to a private corporation or creating some form of public-private partnership, in part to reduce the need for state funding to support seaport development. Privatizing the ports could completely end the role of the Virginia Port Authority, if the public facilities were sold outright.

The board of the Virginia Port Authority decided in 2009 to keep the terminals as state-owned assets, and to operate them without a private partner.

Governor McDonnell, who was elected in late 2009, re-examined that decision. He sought to reduce the costs and the role of state government, and even proposed to sell the state-owned liquor stores. Maintaining the state's deep involvement in private-sector business decisions associated with shipping was inconsistent with his philosophy. A sale of the terminals would also provide a substantial one-time revenue source that could be used to fund highway projects without requiring a tax increase.

Governor McDonnell and his Secretary of Transportation recognized that the ports of New York/New Jersey, Savannah, and Charleston were recovering faster after the 2008 recession. The governor lacked the authority to mandate privatization, but in 2011 he demonstrated the power of his office. He fired 10 of the 12 members on the Virginia Port Authority board. He kept only one member appointed by a previous governor, plus the State Treasurer (who by law is always a member of the Board).

The new Virginia Port Authority board was perceived as having more expertise in managing business operations, and also a higher degree of support for Governor McDonnell's transportation agenda. The 10 new board members had experience running complicated businesses, but they were appointed primarily so the board would be more responsive to Governor McDonnell's priorities.

As noted by the Richmond Times-Dispatch:7

Virginia's governors appoint 11 people to the 12-person board that manages the Virginia Port Authority. Three board members must come from Hampton Roads cities. The governor must appoint one person from Portsmouth or Chesapeake, one from Norfolk or Virginia Beach, and one from Newport News or Hampton.8

The governor justified the firings by the need to have new managers who would make Hampton Roads more competitive as a destination for container ships, and to generate more revenue. The governor was struggling to "fix transportation," his signature issue, but the General Assembly was resisting proposals to increase taxes. Port operations were requiring state subsidies rather than generating a surplus, funds that might be used to finance other transportation projects and help the governor achieve success before his term ended on January 11, 2014.

The governor's new team on the Virginia Port Authority re-examined if the state should sell its port facilities. The new board of also chose to maintain state ownership, rather than auction the terminals to private companies or negotiate a direct deal with a buyer. Gov. McDonnell accepted their decision.

Though the ports were hemorrhaging money during the 2008 recession and revenues from traffic did not cover annual operating costs, the potential for future profits was high. The terminals were viewed as key transportation assets that affected so much economic activity, across the state, that government control was more important than the political agenda for privatization.

infrastructure projects to enhance road and rail access for shipping terminals in Hampton Roads

Source: The Port of Virginia Infrastructure Update - Norfolk (February 16, 2012)

The new Virginia Port Authority board became involved in another complex debate regarding state ownership of a major shipping terminal. In 2009 a Danish company, A. P. Moller–Maersk Group, had spent $450 million to build a new A. P. Moller Terminal (APM) in Portsmouth to handle containerized traffic. It was completed soon after the economy collapsed and shipping traffic declined substantially, and in 2010 the Virginia Port Authority leased the terminal for 20 years.

That lease gave the state control of the newest, most-efficient container processing facility in Hampton Roads until the year 2030, and ensured the Virginia Port Authority would not have significant private competition. The A. P. Moller–Maersk Group got a guarantee of $40 million in annual revenue for 20 years, at a time when profits in the shipping business were thin due to the 2008 recession.

the A. P. Moller Terminal (APM) was renamed Virginia International Gateway (VIG) in 2014

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

That terminal had cost $450 million to construct. The world economy was booming at the start of the 21st Century as China developed, and the A. P. Moller (APM) terminal was the largest private container terminal in the country when constructed. When the major recession hit in 2008, ocean shipping declined substantially.

the A. P. Moller (ARM) terminal was developed by the shipping company that delivers Maersk containers

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk Harbor Navigation Improvements - Draft General Reevaluation Report and Environmental Assessment

The private A. P. Moller (APM) terminal handled shipping from the Maersk line (a related company) and the Evergreen shipping line. However, the Virginia Port Authority had signed long-term contracts with other shipping companies prior to the opening of the new APM terminal. Those contracts were attractive enough for the state-controlled terminals to retain the business of the other shipping lines.

The brand new terminal was underutilized, in part because the state-owned terminals were competing with it. From the view of A. P. Moller–Maersk Group, leasing the terminal guaranteed the private company at least $40 million annually for the next 20 years. That removed the business risk associated with the changes in demand and price-cutting by the state.

In 2012 the company reversed course. APM Terminals (APMT) submitted an unsolicited proposal to privatize all of the state-owned terminals, including the leased APM/Maersk terminal. The private company offered a guaranteed payment, plus variable funding depending upon port volume, for 48 years.

Over the 48 years of the proposed concession contract, Virginia would receive $3.2 billion-$3.9 billion. In addition to converting the ports immediately from a cost center requiring state tax revenue into a profit center, the deal included a major sweetener: at the end of the contract, Virginia would get ownership of the new A. P. Moller Terminal (APM) as well as regain ownership of its other terminals.

World Cargo News made clear how the nascent economic recovery had altered the business strategy of the private shipping company based in Denmark, headlining its story "APMT wants Portsmouth back."9

After conducting a competitive process through the Public-Private Transportation Act of 1995 process, other organizations considered submitting their own bids to operate the ports. VIT, which was independent of the Virginia Port Authority, considered competing. Acquiring the concession would have allowed VIT to retain all revenue from operations, but would increasing costs by requiring regular payments to the state.

In the end, state officials had to choose between APM Terminals and a consortium titled Virginia Port Partners.10

The privatization debate revealed confusion among state officials regarding the costs and benefits from owning the ports. The extent of state funding for construction and subsidies for operations were not clear, the job-related impacts of the Port of Virginia involved more than just the profit/loss statement for the state-operated terminals, and future business conditions were speculative.

Some people thought the ports were financially unstable, even operating at a loss. They argued that a 48-year concession would allow a private corporation to manage more efficiently. Better management was expected to generate immediate revenue for the state, reduce annual operating costs, and eliminate the need for future capital investment to upgrade the terminals.

Others considered the ports to be profit centers for Virginia. They saw high potential for increased revenues after the economy recovered from the 2009-12 recession and the Panama Canal was widened in several more years. The state should retain control of the ports so the public, rather than private shareholders, received the anticipated profits.

the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) and Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT) process containers across the Elizabeth River from Norfolk Southern's coal-export terminal at Lambert's Point

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Virginia Maritime Association opposed transferring control of the state-controlled terminals to APM Terminals. The other shippers viewed A. P. Moller–Maersk Group as a competitor and Virginia International Terminals (VIT) as a neutral operator. Those companies feared the Maersk shipping line would somehow gain advantage if the state transferred control of all terminals to APM Terminals.

Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Newport News were concerned about the impact on tax revenue to the "host communities" of the terminals The state-owned terminals are tax-exempt, but the General Assembly agreed in 2000 to increase the "service charge" paid by the Virginia Port Authority as payment in lieu of taxes to the cities. However, future budgets approved by the General Assembly failed to provide the extra funding.

By the time of the 2012 privatization debate, Norfolk calculated it was receiving only 10% of the state's full payment in lieu of taxes. Norfolk's mayor was concerned that the state would grant new private owners a special tax-exemption in order to maximize the purchase price if the terminals were sold. Portsmouth's mayor noted that the APM terminal paid property taxes, and would be put at a competitive disadvantage if the state granted tax exemptions to other privately-owned terminals.11

the Virginia Port Authority predicts its Hampton Roads capacity will grow from 3.5 million to 9.6 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU) in 25 years, with a new terminal at Craney Island providing the majority of the growth

Source: Virginia Port Authority, 2040 Master Plan

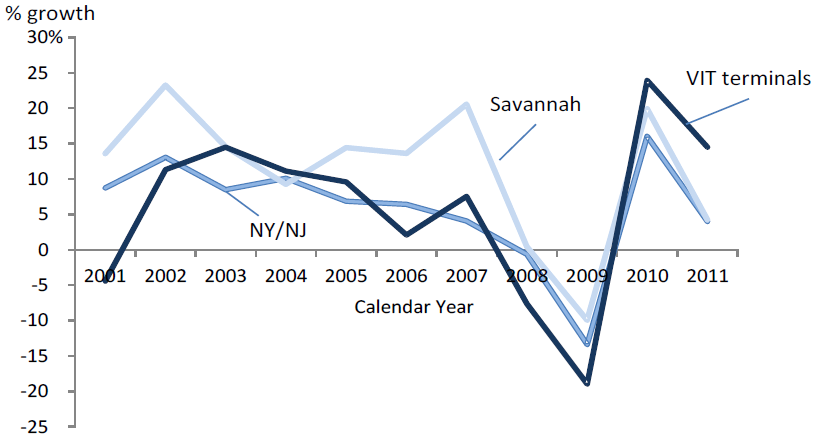

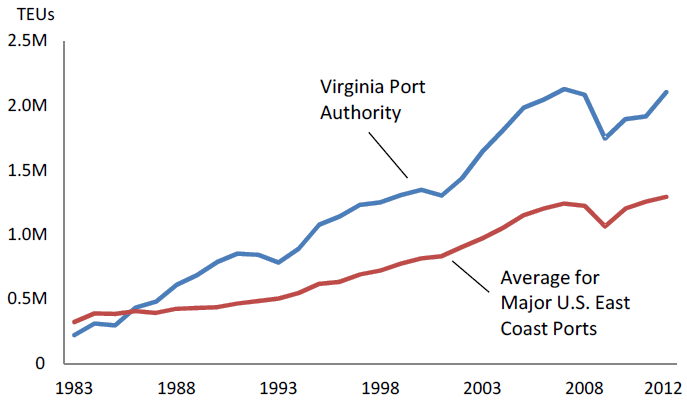

VIT terminals fared worse before - but better after - the recession than the ports of New York, New Jersey, and Savannah

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Special Report: Review of Recent Reports on the Virginia Port Authority’s Operations (Figure 1)

The Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission assessed the competing reports on the costs and revenues of port operations, and concluded:12

There was less public discussion over the potential that privatization would provide several billion dollars of immediate funding. If the ports were leased and generated revenue steadily, then the governor would not need to raise taxes as high to implement his transportation agenda or other priorities. If the governor did not need new laws for new taxes, then he would have less need to bargain with the General Assembly. The Virginia Port Authority board, with 10 new members serving at the pleasure of the governor after 2010, were forced to make a difficult business decision that would have major political impacts.

There were three major choices:13

| Type: | Publicly Owned and Operated | Lease/Concession | Public-Private |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partnership Description: | Port authority is responsible for capital investment in infrastructure and equipment | Port authority leases land to private operator, typically for 30-50 years | Greater responsibility to private sector for infrastructure development |

| Description: | Port authority typically runs yard, gate, and vessel operations | Port authority invests in major infrastructure development and quay wall | Public entities invest in connecting infrastructure (roads, rail, channel) |

| Description: | Port authority may subcontract operations or other to stevedoring company in shorter-term contract | Port operator typically invests in equipment, buildings, and paving to ready the land for operational use | Private operator invests in major port infrastructure, taking increased risk in return for a long-term concession |

| Examples: | Savannah; Charleston; Houston; Kingston | Los Angeles; New York; New Jersey; Tacoma; Jacksonville; Miami; Oakland | Vancouver; Mobile; ~Virginia |

In 2013, the Virginia Port Authority board decided to maintain state ownership. All proposals to privatize the ports were rejected, and port operations were streamlined.

containers at A. P. Moller Terminal (APM) - now Virginia International Gateway (VIG) - are loaded by gantries from a ship onto a chassis, and that chassis is then moved to a portion of the yard where another gantry loads the container onto a truck

Source: Wikipedia, Intermodal freight transport

The independence of the VIT was reduced when the state converted VIT into a limited liability corporation (LLC) and the VIT board into just an advisory body to the Virginia Port Authority board in 2013. In a cost-cutting measure, many of the administrative support functions of VIT and Virginia Port Authority were consolidated.

Three VIT Board members resigned in protest. They highlighted concerns that Virginia Port Authority officials, who were appointed by the governor, would have too much opportunity for political interference in the business side of port operations. Back in 2009, the General Assembly's joint subcommittee to study the potential of public-private partnerships for seaports included in its final report:14

In 2014, newly-elected Governor McAuliffe replaced five members on the board of the Virginia Port Authority. He reappointed former state Transportation Secretary John Milliken, who had been removed by Governor McDonnell.

The new board discovered one reason for Virginia's ability to attract more containers: in 2012, during the privatization debate, incentives for shippers were increased so much that the state's terminals at Norfolk and Portsmouth lost money. Shippers had been incentivized by discounts to send business to Virginia, and 75% of the workers transferring the surge of containers to rail cars were paid overtime.

According to Governor McAuliffe's Secretary of Transportation:15

The higher cargo volumes did not generate higher profits. Instead, the discounts caused the ports to lose more money as traffic increased. The ports lost money when the recession began in 2008, but even after the economy recovered it continued to lose money. The loss in 2013-14 was $17.1 million, more than the $15.5 million deficit in 2012-13.16

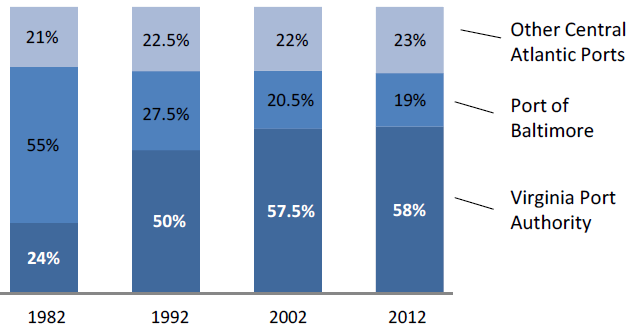

Virginia Port Authority terminals have gained market share from competitors since 1982 - but profitability after 2012 was significantly impacted by incentives given to shippers to steer business to Hampton Roads

Source: Joint Legislative and Audit Review Commission, Review of the Virginia Port Authority’s Competitiveness, Funding, and Governance (Figure 6)

The VIT contracts providing extra incentives and creating economic losses were not revealed to the Virginia Port Authority in 2012 or 2013. The VIT board, which in 2012 was still an independent body separate from the Virginia Port Authority board, was opposed to sale/lease of the ports. Once the ports were controlled by a private corporation, the prohibition against state agencies negotiating with unions would be irrelevant - and there would be no need for a state-chartered VIT to negotiate union contracts with the International Longshoremen’s Association.

The discounts created short-term losses, but the extra traffic suggested business was recovering and helped defeat privatization proposals. A former member of the Virginia Port Authority Board made clear his suspicions that there was a connection between the incentives and the threat to replace VIT through privatization:17

Another noted the lack of transparency between VIT and the Virginia Port Authority:

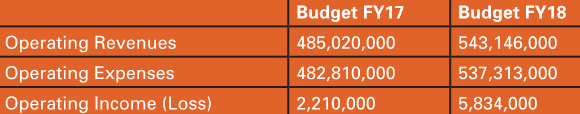

By 2017, the management realignments had succeeded. The Port of Virginia was making a profit again.

the Port of Virginia was profitable again in 2017

Source: Port of Virginia, 2017 Annual Report (p.21)

The state negotiated a new lease to extend control of the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) until 2065, and the General Assembly agreed to invest $320 million into expanding it. The legislature also approved a $350 million expansion of the Norfolk International Terminals, and the Port of Virginia advertised it was "Big Ship Ready" for the post-Panamax container ships.18

the Port of Virginia has competed successfully against other East Coast ports to increase container volume over the past 30 years

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Review of the Virginia Port Authority's Competitiveness, Funding, and Governance (2013)

truck drivers are key to the transport of the majority of containers at Virginia Port Authority terminals

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation Flickr site, Norfolk International Terminals (NIT), Port of Virginia

1. Kristen Monaco, Lindy Olsson, "Labor at the Ports: A Comparison of the ILA and ILWU," METRANS Transportation Center, Research Grant AR 04-02, 2004, pp.5-6, http://www.metrans.org/research/final/AR%2004-02_final_draft.pdf (last checked June 4, 2013)

2. "Ten years after: supply chain reminded of West Coast lockout as it plans for possible work stoppage in the East, Gulf," DC Velocity, June 25, 2012, http://www.dcvelocity.com/articles/20120625-possible-work-stoppage-in-the-east-gulf-/ (last checked June 4, 2013)

3. Roy L. Pearson, James R. Bradley, K. Scott Swan, Hector H. Guerrero, "Economic Impact Study: Port of Virginia," College of William & Mary Mason School of Business, January 8, 2008, p.ii, p.3, https://www.wm.edu/offices/economicdevelopment/_documents/reports/finalvaeconimpactstudywithcover.pdf; Roy L. Pearson, K. Scott Swan, "The Fiscal Year 2013 Virginia Economic Impacts of the Port of Virginia," College of William & Mary Mason School of Business, p.5, p.12, http://www.portofvirginia.com/pdfs/POV%20Econ%20Impact%20Study%202014.pdf (last checked November 16, 2016)

4. Christopher Dinsmore, "Leader reflects on how far union, port have come," The Virginian-Pilot, September 6, 2004, home.hamptonroads.com/stories/story.cfm?story=75231&ran=227698 (last checked September 6, 2004)

5. Artist v. Virginia Intern. Terminals, Inc., 679 F. Supp. 587 (E.D. Va. 1988)," U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, February 10, 1988, http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/679/587/1529356/ (last checked July 8, 2016)

6. USMX Members Ratify New Six-Year Master Contract," United States Maritime Alliance Labor Updates, April 17, 2013 press release, http://usmxlaborupdates.com/static/uploads/general-images/USMX_Contract_Vote_4-17.pdf; "4-hour closure at local port will allow for talks," The Virginian-Pilot, June 4, 2013, http://hamptonroads.com/2013/06/4hour-closure-local-port-will-allow-talks (last checked June 4, 2013)

7. "Virginia Port Authority board members installed," Richmond Times-Dispatch, July 27, 2011, http://www.timesdispatch.com/business/virginia-port-authority-board-members-installed/article_0bb042f1-0d7e-5307-bf65-51808b011c2b.html (last checked May 31, 2013)

8. "Board of Commissioners; members and officers; Executive Director; agents and employees," § 62.1-129, Code of Virginia, http://leg1.state.va.us/cgi-bin/legp504.exe?000+cod+62.1-129 (last checked May 31, 2013)

9. "Unsolicited Proposal Received under the Public-Private Transportation Act to Operate Port of Virginia," Port of Virginia, May 12, 2012, http://www.p3virginia.org/unsolicited-proposal-received-under-the-public-private-transportation-act-to-operate-port-of-virginia/; "APMT wants Portsmouth back," World Cargo News, May 2012, http://www.worldcargonews.com/htm/t20120609.124785.htm (last checked July 8, 2016)

10. "Information about Proposals to Operate the Port of Virginia, Virginia Maritime Association, http://www.vamaritime.com/?page=AMPBids (last checked July 13, 2013)

11. "Cities bearing burden of ports expect compensation," The Virginian-Pilot, September 13, 2009, http://pilotonline.com/business/ports-rail/cities-bearing-burden-of-ports-expect-compensation/article_f3444c7e-5444-52fe-a338-3361839e05f0.html (last checked July 10, 2016)

12. "Special Report: Review of Recent Reports on the Virginia Port Authority’s Operations," Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Report Document No. 8, January 2013, http://leg2.state.va.us/dls/h&sdocs.nsf/4d54200d7e28716385256ec1004f3130/f98658b1b82bc43d85257af00056e2e3?OpenDocument (last checked July 13, 2013)

13. "Public-Private Partnerships Related to Seaports in Virginia (HJR 72, 2008)," Report of the Joint Subcommittee Studying Public-Private Partnerships Regarding Seaports in Virginia, House Document No. 25, 2009, p.23, http://dls.virginia.gov/GROUPS/ports/reports.htm (last checked July 8, 2016)

14. "Port reorganization creates storm at VIT," Daily News (Newport News), May 30, 2013, http://www.dailypress.com/business/ports/shipping-news-blog/dp-virginia-port-authority-reorganization-creates-storm-at-vit-20130530,0,3734135.post; "Public-Private Partnerships Related to Seaports in Virginia (HJR 72, 2008)," Report of the Joint Subcommittee Studying Public-Private Partnerships Regarding Seaports in Virginia, House Document No. 25, 2009, p.36, http://dls.virginia.gov/GROUPS/ports/reports.htm (last checked July 8, 2016)

15. "Calmer seas," Virginia Business, August 28, 2014, http://www.virginiabusiness.com/news/article/calmer-seas (last checked July 10, 2016)

16. "Port sinks to sixth straight fiscal-year loss," The Virginian-Pilot, August 19, 2014, http://hamptonroads.com/2014/08/port-sinks-sixth-straight-fiscalyear-loss (last checked July 10, 2016)

17. "Under-the-radar incentives eroding port's bottom line," The Virginian-Pilot, May 27, 2014, http://hamptonroads.com/node/717670; "New board, new plan for Virginia Port Authority," The Virginian-Pilot, May 28, 2014, http://hamptonroads.com/2014/05/new-board-new-plan-virginia-port-authority (last checked May 28, 2014)

18. "2017 Annual Report," Virginia Port Authority, 2018, p.8, p.12, p.21, http://www.portofvirginia.com/about/annual-report/ (last checked March 5, 2018)