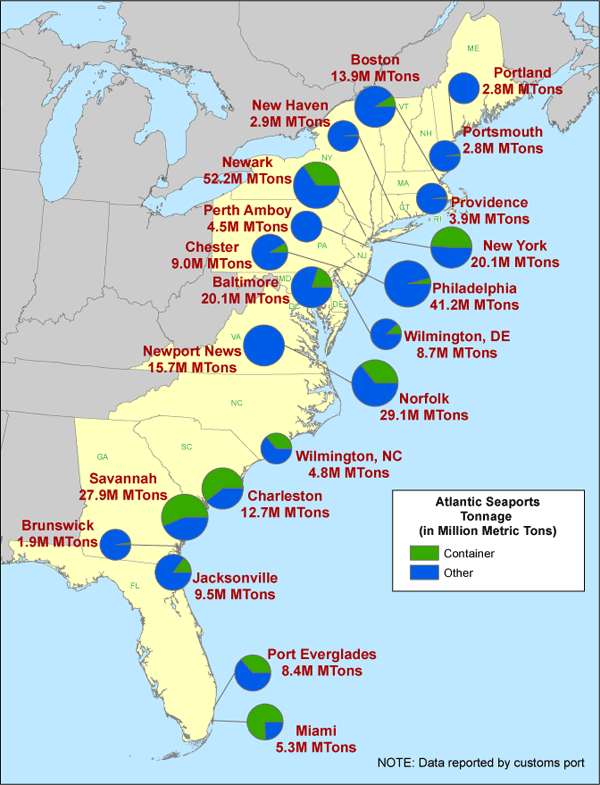

in 2009, Norfolk edged out Savannah to take second place among East Coast ports for total tonnage of cargo handled

Source: US Department of Transportation, Atlantic Port Call by Tonnage, 2009)

in 2009, Norfolk edged out Savannah to take second place among East Coast ports for total tonnage of cargo handled

Source: US Department of Transportation, Atlantic Port Call by Tonnage, 2009)

Virginia's major ports are in competition with other ports on the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico, New York to Houston. Virginia also competes with West Coast ports, from San Diego to Vancouver. The worst case scenario is that competing ports would complete their channel deepening projects first, and ocean shippers would make Virginia's ports just a secondary destination.

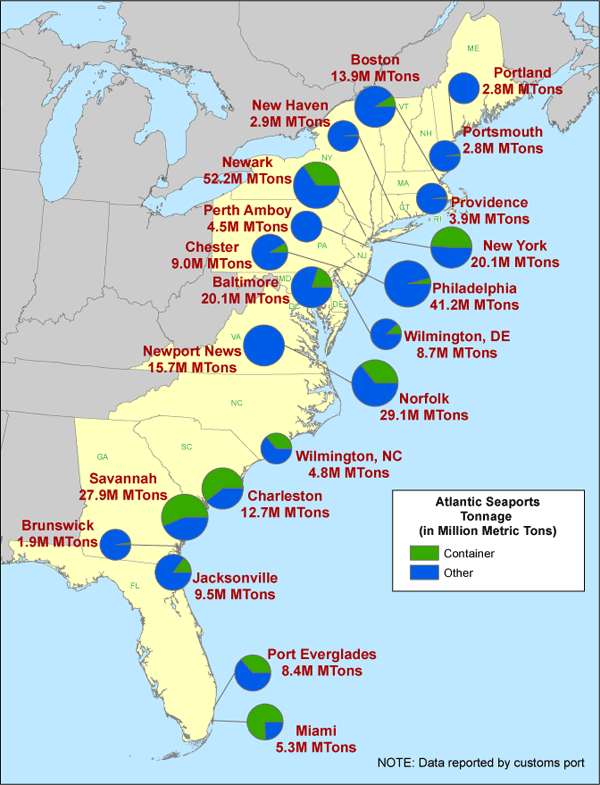

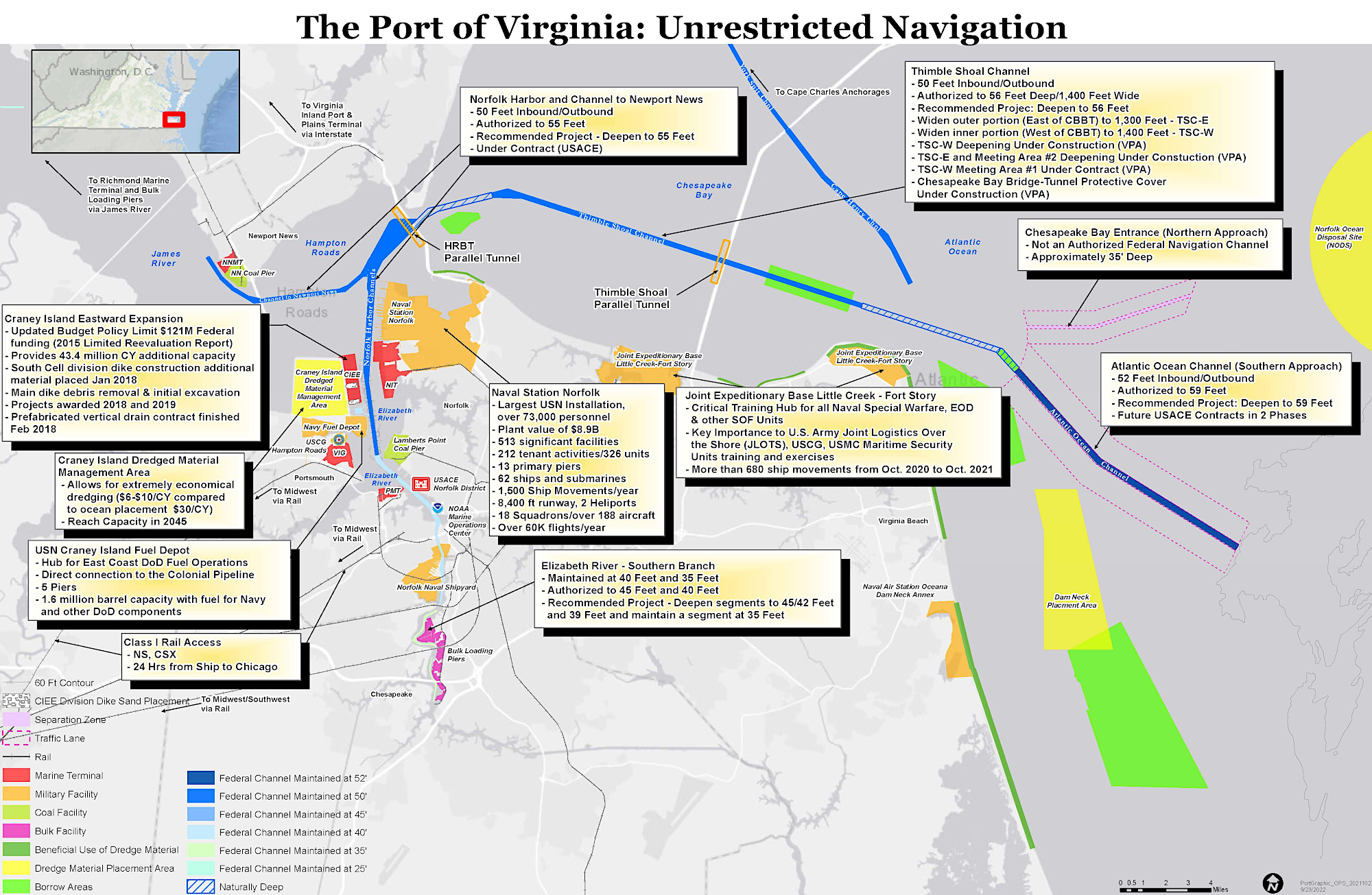

Hampton Roads tunnels allow for navigable waterways above them to be 35' to 55' deep

Source: Federal Highway Administration, National Tunnel Inventory

Manufacturers from Asia can deliver goods in a 40-foot or 53-foot shipping container to Los Angeles, where the shipping channel is 53' deep. Containers are loaded on a train headed to Chicago, St. Louis, or even destinations on the East Coast. Such multi-modal shipping can be faster than the all-water route through the Panama Canal to Norfolk, Portsmouth, or Newport News.

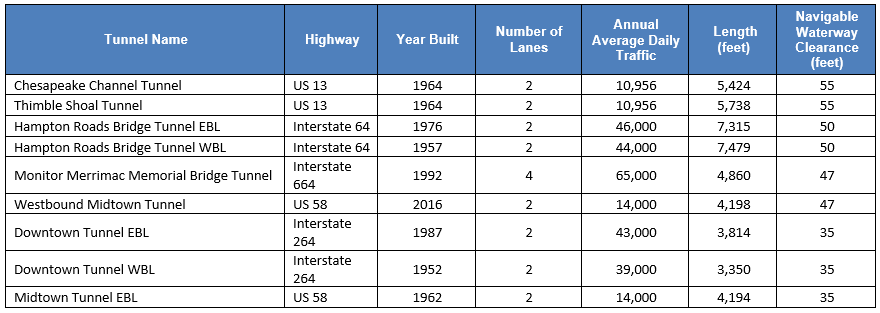

most cargo going through Norfolk International Terminal (NIT) is containerized

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Port of Virginia relies heavily upon Federal funding to maintain and even deepen the existing shipping channels. The military presence in Hampton Roads helps get Congressional support for appropriations to improve the shipping channels and the local transportation network, both rail and highway.

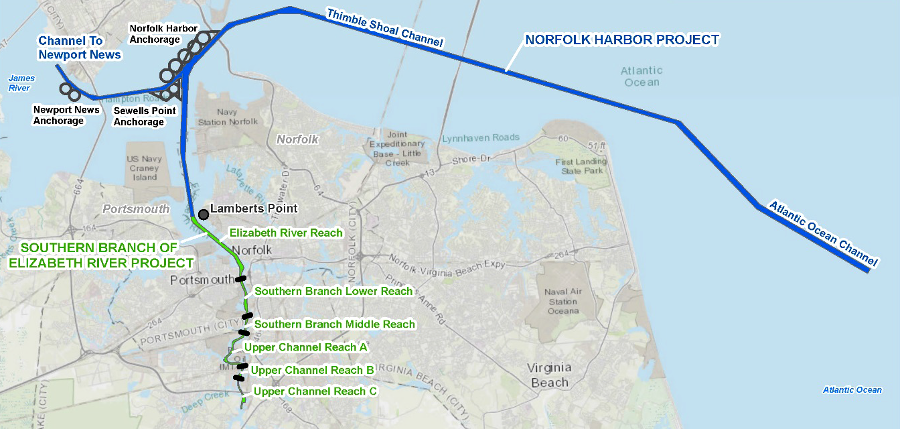

To support the US Navy and civilian traffic, the US Army Corps of Engineers has maintained a 50' deep shipping channel from the Atlantic Ocean to terminals in Hampton Roads (being deepened now), and a 25' deep channel up the James River to Richmond. The Corps also dredges a shipping channel for traffic going north to Baltimore.

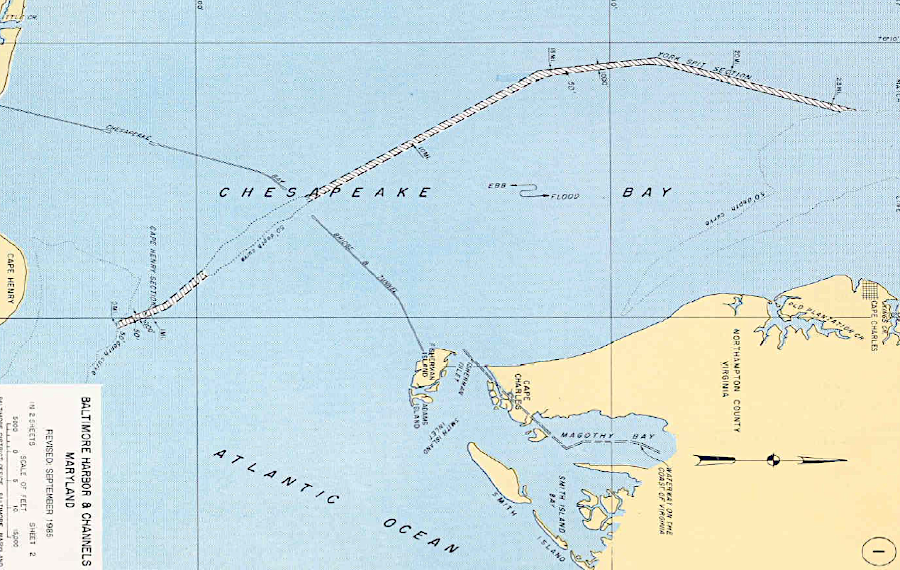

the US Army Corps of Engineers maintains a shipping channel in the Chesapeake Bay for ships going to Baltimore

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Fact Sheet, Baltimore Harbor & Channels, Maryland and Virginia (January 2006)

Virginia claims to have "the deepest natural harbor on the east coast" at Norfolk, but that claim ignores the natural harbor at Eastport, Maine. That town's harbor is deeper at 60+ feet, and the granite bedrock bottom does not require regular dredging. Eastport has an appropriate name.

Eastport is the closest US port to Europe, Africa - and Asia, once ships start to use the Northwest Passage as the ice in the Arctic Ocean disappears. However, Eastport lacks transportation links inland. There is no rail line, and Route 1 is only a two-lane highway headed south.1

Hampton Roads offers several ports with excellent rail and road connections to inland customers. The need to deepen the natural channel was triggered initially by the construction of large warships at the U.S. Navy Yard, Norfolk (now Norfolk Naval Shipyard).

The first battleships and aircraft carriers found it difficult to use the channel in the Elizabeth River, which was only 28 feet deep in some spots. On December 18, 1903, the Virginian-Pilot reported the Wright brothers had succeeded in flying a plane at Kitty Hawk, and just below that headline was a story about a Federal proposal to study dredging the channel to 30-35 feet in depth.

The initial efforts to get funding from the US Congress for river and harbor improvements failed, but between 1917-1927 the Federal government enhanced the natural channel to ensure a minimum depth of 40 feet from the mouth of the Chesapeake to Newport News, Norfolk, and Portsmouth. In 1967, the channel was dredged to 45 feet. Between 1987-2007, it was deepened again to 50 feet.

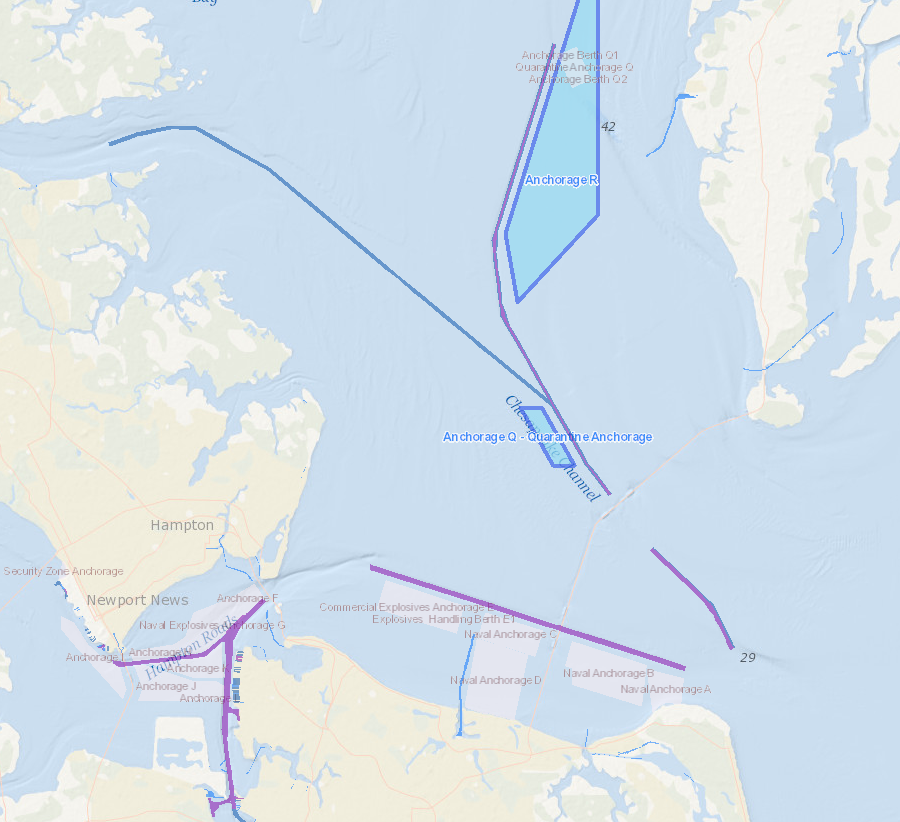

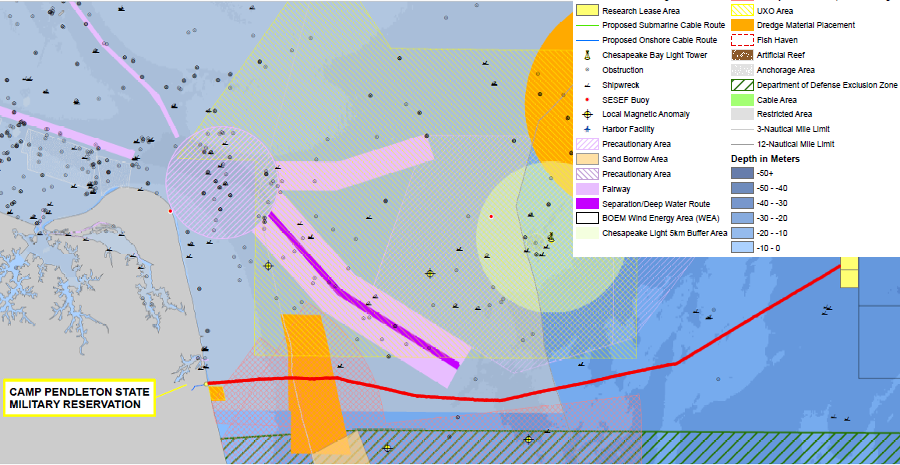

The US Coast Guard is responsible for designating the Hampton Roads Anchorage Grounds. Two sites, Anchorage R and Anchorage Q, were identified based on exposure to weather, tug and barge traffic density, navigational safety, and efforts to protect vistas from nearby shorelines.concerns2

the US Coast Guard has identified anchorage sites R and Q near the Chesapeake Channel, maintained for ships going north to Baltimore

Source: Mid-Atlantic Ocean Data Portal

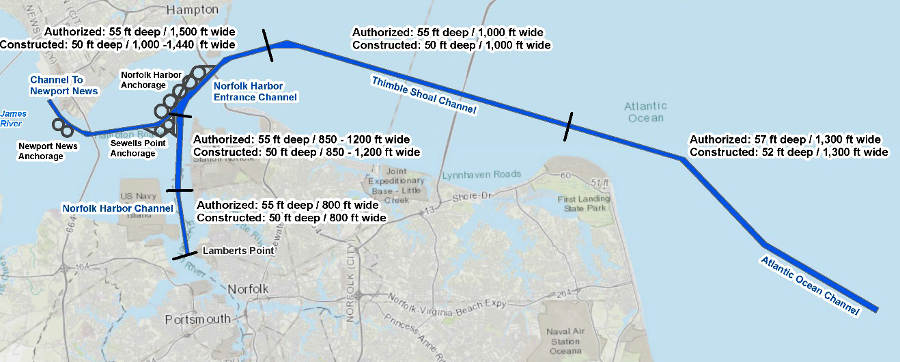

The 11-mile long Atlantic Ocean Channel, from the deep ocean to the Thimble Shoals channel, was authorized in 1986. It was dredged in 2006 to a depth of 50 feet.

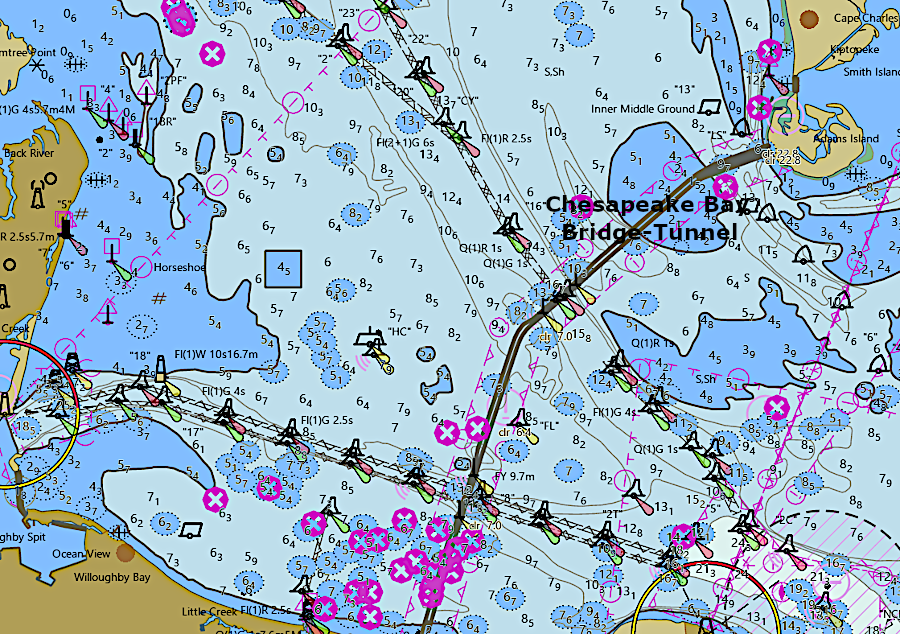

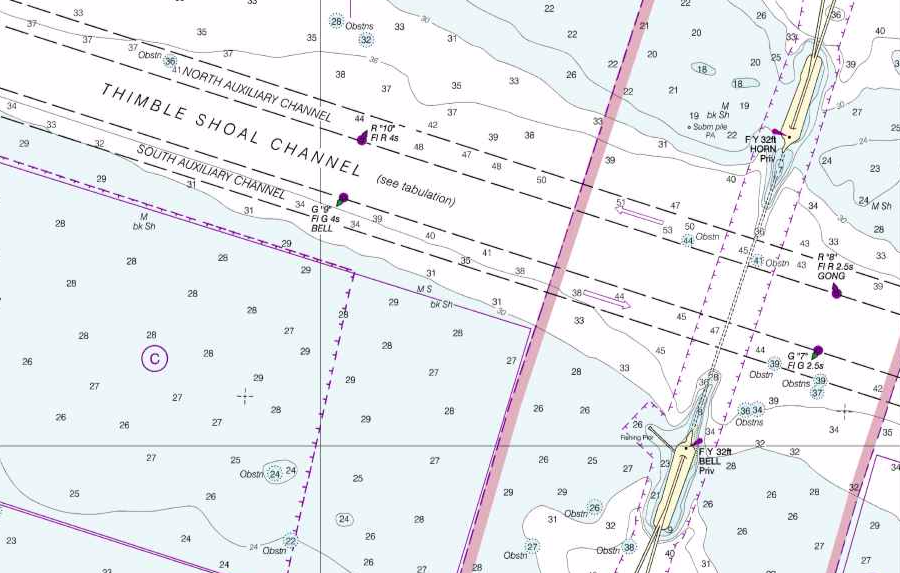

A 50-foot deep shipping channel is currently maintained from Thimble Shoals to terminals in Norfolk and Newport News by regularly dredging the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay, Elizabeth River, and James River. The Thimble Shoals channel is 1,000 feet wide, but to avoid collisions ships using the inbound channel above the Thimble Shoals tunnel of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel follow a route that is 350 feet wide and 50 feet deep while the outbound ships use a route that is 650 feet wide and 50 feet deep.

dredged channels west of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel lead west to Norfolk/Newport News and north to Baltimore

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), NOAA ENC Viewer

One of the 45 harbor pilots based at Lynnhaven Inlet in Virginia Beach guides vessels the 11 miles through the Atlantic Ocean Channel, 12 miles through the Thimble Shoals Channel, and the remaining 5 miles to the terminal where cargo is unloaded and loaded.

Pilots are not always successful. On March 13, 2022, the 1,095-foot long ship Ever Forward with 4,900 containers aboard ran aground at a bend in the shipping channel while traveling south from Baltimore to Norfolk. The pilot was distracted, using his phone, and was late in calling for the ship to make a right turn.

The ship was freed a month later after removing 500 containers and excavating 20 feet of mud. Choosing which containers to remove was a challenge. Distribution of weight had to be calculated to prevent the hull from cracking as the forces were altered.

the Ever Forward ran aground in 2022 after the pilot was late in calling for a right turn, and finally freed a month later

Source: Coast Guard News, Grounded container ship refloated in the Chesapeake Bay

Dredging to 55 feet mean lower low water (the averaged lowest of the low tide, or tides, per day) and widening the channel to 1,000 feet was authorized when the US Congress passed the Water Resources Development Act (WRDA) of 1986. Getting the funding was a separate exercise than getting authorization for a river and harbor project. The US Congress initially appropriated enough funding to dredge a 50-foot deep channel, but not deeper.

A key step of obtaining more Federal funding was crossed in 2018, when the Army Corps of Engineers endorsed the deepening/widening project. That cleared the way for including it in the next Water Resources Development Act to e passed by the US Congress.

The Virginia General Assembly acted earlier in 2018 to commit state funding, and the 2018-20 biennial budget included $350 million for the channel deepening project. The state projected that bigger ships using a deeper channel could bring another 1,000,000 containers to the Port of Virginia, increasing capacity by 40%.3

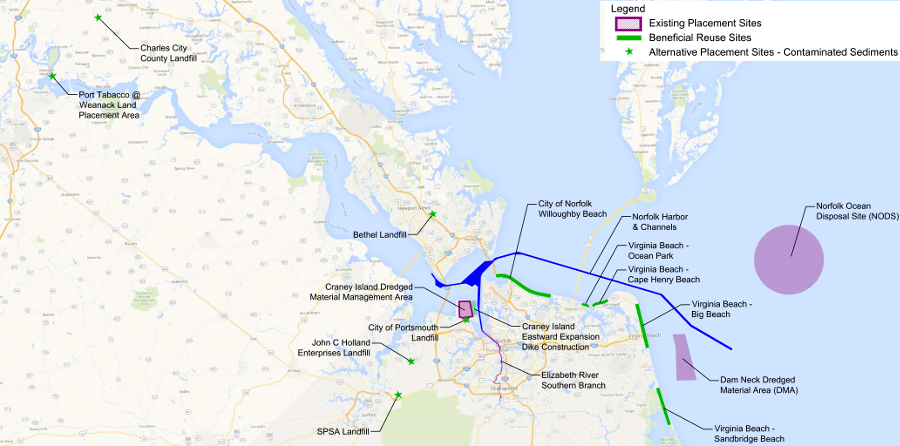

the US Army Corps of Engineers dredges the shipping channels in Hampton Roads

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Bathymetric Data Viewer

A 1,500 feet wide and 50-foot deep channel is maintained from Thimble Shoals to Norfolk International Terminals (NIT). A narrower 800-foot wide and 50-foot deep channel extends further south in the Elizabeth River to Norfolk Southern's Lambert's Point coal exports piers. The Elizabeth River is dredged further to its southern end in order to maintain a 250-foot wide, 35-foot channel connecting to the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway. The Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2024 provided $4 million to plan for deepening the Elizabeth River's 40-foot channel to 42 feet, and in some places to 45 feet. The US Army Corps of Engineers will also plan to deepen the 35-foot channel in the Southern Branch to 39 feet.

Thanks to dredging a deep channel near the mouth of the Elizabeth River, Norfolk Southern can load outbound coal ships at Lamberts Point so the bottoms sink 50-feet deep into the water at high tide. Some coal ships calling at the terminal are large enough to require a 60-foot draft, if fully loaded.

Because container ships are harder to maneuver in the channels, inbound and outbound container ship traverse Thimble Shoals at high tide when the water is at least 49 feet, 3 inches deep. Ships with a draft no greater than 47 feet may use the channels at low tide.4

The 800-foot wide, 50-foot channel to Newport News International Terminal (NNIT) is authorized for deepening to 55 feet. No funding has been allocated yet for altering that channel.5

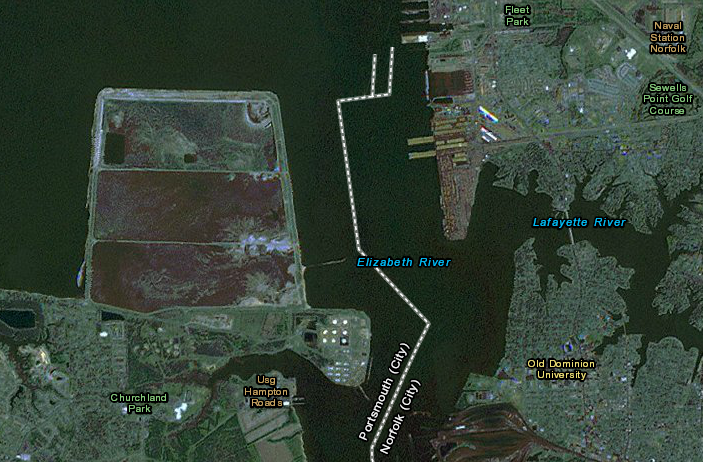

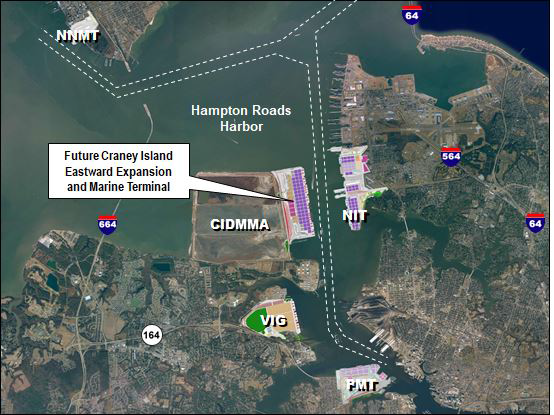

Craney Island, like the Norfolk Navy Yard, is located within the city boundaries of Portsmouth - across the Elizabeth River from the Norfolk Naval Base within the city of Norfolk

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), Wetlands Mapper

Since 1957, mud, sand, rocks, shells, and other material scraped up from the bottom ("dredge spoils") has been deposited into one of three cells at the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area. One cell receives fresh dredge spoils, while two others are drying out.

The Corps identified that the Craney Island site would reach capacity in 2025 at the same time the Virginia Port Authority predicted that its Hampton Roads terminals would reach capacity in 2011. A new terminal, and an expanded dredge spoil deposit site, were needed. There was a solution to both problems: expand the Craney Island disposal site eastward into the Elizabeth River, and construct a new marine terminal on the newly-formed land created from the additional dredge spoils.

Congress approved the plan, though funding for full implementation is not guaranteed. The Virginia Port Authority urgency to construct the Craney Island Marine Terminal before 2028 eased, after the state agency extended the lease of the privately-owned Virginia International Gateway (VIG) terminal in Portsmouth from 2028 to the year 2065.6

Savannah processes more Twenty-foot Equivalent Units (TEU's) in international trade than Norfolk, but that statistic does not include break bulk cargo

Source: US Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration, U.S. Waterborne Foreign Container Trade by U.S. Custom Ports)

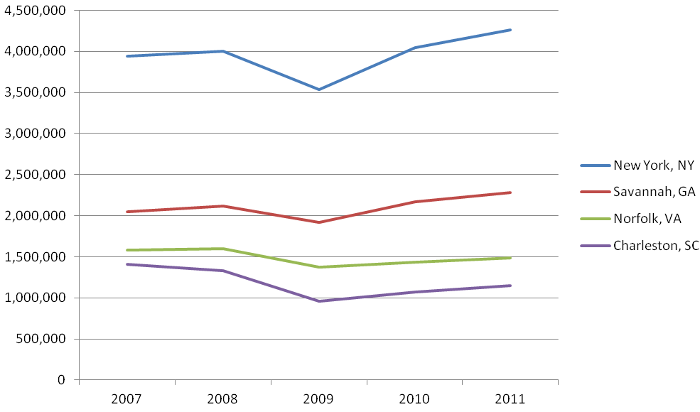

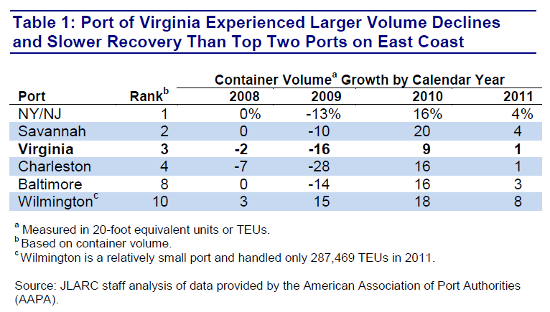

the slow recovery from the 2008-2011 recession triggered proposals to privatize the state-owned terminals in Hampton Roads

Source: Virginia Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC), Special Report: Review of Recent

Reports on the Virginia Port Authority's Operations (Table 1)

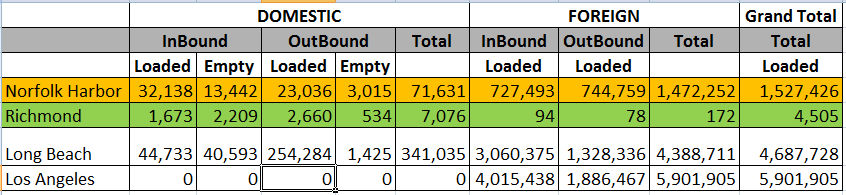

Norfolk has an even balance of container imports and exports, unlike the ports at Los Angeles

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers Waterborne Commerce Statistics Center, U.S. Waterborne Container Traffic by Port/Waterway in 2011

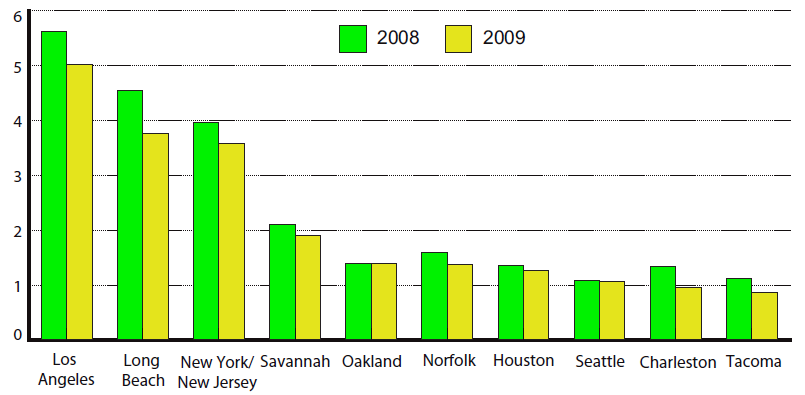

The depth of Norfolk's shipping channel affects its competition with more than just Savannah, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York/New Jersey, and even the Gulf Coast ports such as New Orleans. Ships can steam across the Pacific Ocean to West Coast ports in 12 days, and containers can be carried by train/truck to East Coast destinations in another 5-8 days. Ships going through the Panama Canal to an East Coast port require 24 days, so Norfolk also competes with Los Angeles, Seattle, and other West Coast ports.

Widening of the Panama Canal created the potential to divert ships from West Coast ports such as Los Angeles to the East Coast. Bigger Post Panamax Generation 3 vessels (PPX3) allowed more containers to be brough directly to the East Coast, rather than transported cross the continent by rail from West Coast ports to customers east of the Mississippi River.

In 2017, the first year after the expanded canal opened, container traffic at East Coast ports increased because overall customer demand increased - not because ships previously going to the West Coast changed destinations. The Panama Canal did see an increase in shipping, but it was due to ships that previously had traveled via the Suez Canal choosing to go in the other direction.7

California ports dominate the foreign container trade, as measured in twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU's), reflecting the significance of Asian imports

Source: U.S. Department of Transportation, Research and Innovative Technology Administration, America's Container Ports: Linking Markets at Home and Abroad (Figure 2, January 2011)

Hampton Roads has advertised a 50-foot outbound channel since it was dredged in 1989 to accommodate large ships exporting heavy loads of coal, and a 50-foot inbound channel since that dredging was completed in 2007. Norfolk International Terminals (NIT) loaded container vessels that required a 49-foot channel to exit through the Chesapeake Bay.

The Port of Virginia competes with other states in part because no other port exceeds the depth of the Hampton Roads channel. A least one shipping line designed port visits to include a "last stop" at Norfolk, topping off a large container ship's load there because other ports with shallower channels could not accommodate a fully-loaded vessel.

The Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel under the Thimble Shoal Channel, the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel under the Norfolk Harbor Channel, and Monitor-Merrimac Bridge-Tunnel under the Newport News Channel are buried at least 63 feet deep below the bottom, so the challenge to dredge deeper is financial rather than physical. Virginia's elected officials and business leaders consistently lobby the US Congress to fund its already-authorized plans to dredge and widen the inbound and outbound channels so large ships could maneuver safely.

With a deeper and wider shipping channel, the Port of Virginia argued that it could compete better against Baltimore, Miami, and New York/New Jersey, the three rival East Coast ports that also have 50-foot deep shipping channels. A project to deepen the Delaware River shipping channel from 40 feet to 45 feet was completed in 2021, and Philadelphia Regional Port Authority (PhilaPort) quickly began seeking authorization and funding to dredge the channel to 50 feet.

the planned submarine cable to bring electricity onshore from offshore wind turbines (highlighted with red line) was routed to avoid the deep inbound channel dredged by the US Army Corps of Engineers in the Outer Continental Shelf

Source: Dominion, "Virginia Offshore Wind Technology Advancement Project," Offshore Constraints

Until 2017, the Port of Virginia did not handle ships larger than 10,000 TEU's (i.e., ships carrying 5,000 containers that were each 40-feet long). The existing 50-foot deep shipping channel was not the constraint, however. Once the port increased container-handling equipment and procedures for moving containers on land in 2017, it was able to attract ships carrying 13,000-14,000 TEU's each week.

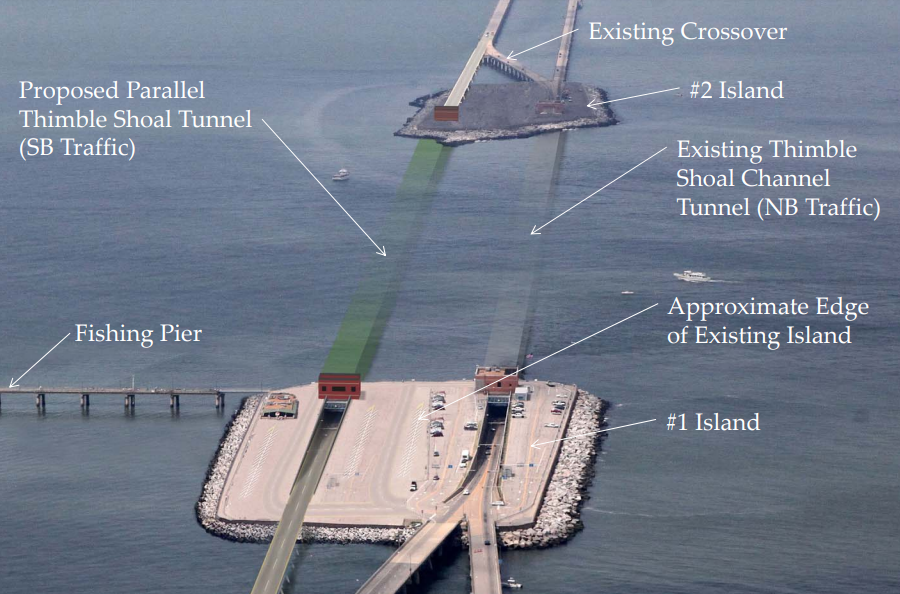

The Virginia Maritime Association still described widening and deepening the channel as the #1 priority for upgrading port infrastructure at Hampton Roads. During part of the four hours required to move an Ultra-Large Container Vessel (ULCV) 28 miles from the Atlantic Ocean to the Norfolk International Terminal (NIT), the 1,000-foot wide channel at the Thimble Shoal islands of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel was made into a one-way route. Restricting traffic to just one direction there until the ship passed created delays for other vessels.

The Virginia Maritime Association advocated that the Corps of Engineers and Port of Virginia eliminate the one-way bottleneck by dredging the Thimble Shoal channel to 55 feet deep and 1,400 feet wide.

widening the Thimble Shoal channel 400 more feet would allow two-way traffic of Ultra-Large Container Vessels (ULCV's)

Source: Virginia Business, Tight Squeeze (August 30, 2017)

The proposal for a 1,400 feet wide channel represented the maximum possible width. In 2017, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel began constructing a new tunnel at Thimble Shoal, parallel to the existing tunnel. The new tunnel will use the existing man-made islands at either end. The Thimble Shoal shipping channel can be widened, without building another set of islands and replacing very expensive underwater tunnels, to a limit of 1,400 feet.8

the Thimble Shoal channel between the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel islands is 1,000 feet wide

Source: OceanGrafix, Chesapeake Bay Thimble Shoal Channel (NOAA Nautical Chart 12256)

construction began in 2017 of a parallel tunnel at the Thimble Shoal channel, using existing islands and assuming no widening of the channel beyond 1,000 feet

Source: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Commission, Request For Qualifications Showing (May 28, 2015)

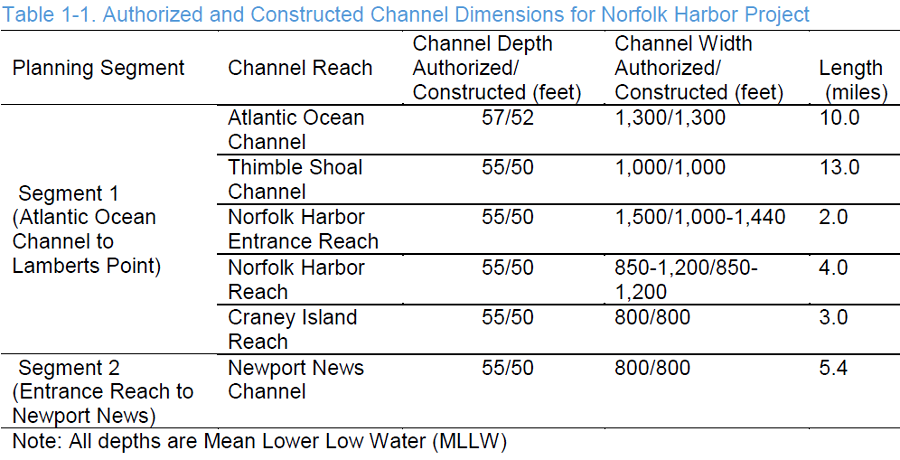

In late 2017, the US Army Corps of Engineers recommended channel alterations in Hampton Roads that included widening the Thimble Shoal channel to 1,200 feet. Dredged materials ("spoil") would be deposited at the Dam Neck Ocean Disposal Site, the Norfolk Ocean Disposal Site, or the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area.

in 2017, the US Army Corps of Engineers recommended further widening and deepening of Hampton Roads shipping channels

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk Harbor Navigation Improvements - Draft General Reevaluation Report and Environmental Assessment (Figure 1-1)

Overall, the changes would cost over $320 million, and the Corps estimated a benefit/cost ratio over the next 50 years of 4.93 (assuming interest rates at 2.75%). The Federal government would pay 45.6% and the state would pick up the remaining costs for:9

The Corps committed to develop recommendations for the Elizabeth River Southern Branch (ERSB) Navigation Improvements project in a separate study.

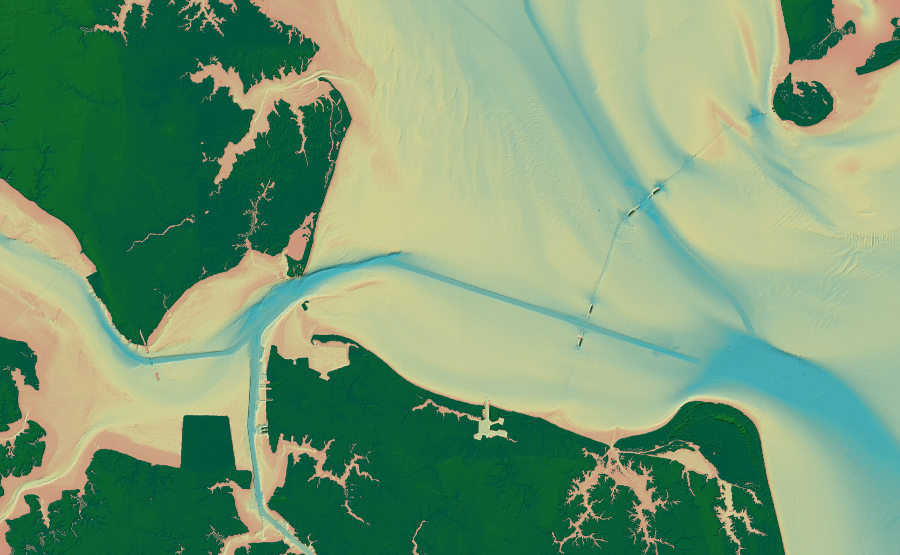

the US Congress has authorized dredging existing Hampton Roads shipping channels beyond their current dimensions, but has not funded further expansion

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk Harbor Navigation Improvements - Draft General Reevaluation Report and Environmental Assessment (Figure 1-2)

in 2017, the US Army Corps of Engineers recommended deepening and widening existing shipping channels at Hampton Roads more than currently authorized

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk Harbor Navigation Improvements - Draft General Reevaluation Report and Environmental Assessment (Table 1-1)

Constant dredging is required to keep the channels at their advertised depth. The US Army Corps of Engineers calculates every year which portion of which channel needs maintenance.

On occasion, emergency dredging is required. In 2011, a bulk carrier loaded with coal ran aground in the middle of the Thimble Shoals channel. The ship required only 47 feet of depth, so no one expected it to hit bottom in the 50-foot channel. Slumping sediments and Chesapeake Bay currents had filled the channel until it was only 41.1 feet deep.

The ship anchored to assess damage, which is standard operating procedure. The collier immediately became a roadblock in the shipping lane and threated to shut down traffic, causing very expensive delays in commercial shipments and preventing US Navy vessels from making scheduled port calls. Tugs pulled the ship free at high tide, the Corps directed hopper dredges working nearby to scrape out the channel to its standard depth and width, and delays ended up being minimal.10

Disposal of materials dredged from the shipping channels requires a permit from the US Army Corps on Engineers. If deposited in the ocean, only sites authorized by the Environmental Protection Agency may be used.11

When not needed for beneficial uses to widen the beach at Virginia Beach, Willoughby Spit, and Sandbridge or to construct dikes at the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area, the excess dredge spoils from the Atlantic Ocean Channel and the clay-rich material dredged from the Thimble Shoal Channel are deposited at the nearby Dam Neck Ocean Disposal Site (DNODS).

Spoils from dredging between Sewells Point and Lamberts Point on the Elizabeth River, the Newport News channel, and the associated anchorages are deposited at the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area. Costs to haul the dredge spoils to an alternative disposal site in the Atlantic Ocean would be higher, and some of the material is too contaminated from old industrial operations around the harbors to permit disposal at sea.

sediments dredged from the Elizabeth River, the Newport News shipping channel, and associated anchorages are deposited at the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Some sediments are dumped at the Dam Neck Ocean Disposal Site (DNODS), also known as the Dam Neck Ocean Dredged Material Disposal Site (ODMDS) and the Dam Neck Dredged Material Area (DNDMA). An alternative location, further offshore, is the Norfolk Ocean Dredged Material Disposal Site.12

sediments dredged to maintain ship channels in Hampton Roads can be deposited in multiple locations

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Dredged Material Placement Options

One factor in dredging at Hampton Roads is the risk if unexploded ordinance. Since colonial days, shells fired into the water have sunk to the bottom without exploding. Though many have been waterlogged and become inert, dredge boat captains know that they may retrieve some shells that could be dangerous.

Over 200 hundred underwater mines planted to deter German submarines during World War II were never recovered, and both torpedoes and depth charges may be encountered. In 1965, eight men were killed when a trawler dredging for scallops snagged a torpedo 58 miles southeast of the Atlantic Ocean Channel.13

The Corps of Engineers has identified a variety of historic shipwrecks to avoid when dredging or depositing spoils from the channels. One archeological resource is the remains of the U.S.S. Cumberland, a Union ship sunk by the new C.S.S. Virginia ironclad in the Civil War.

Two major fiber optic lines, buried less than five feet deep on the Outer Continental Shelf, now link Virginia Beach to Europe and South America. The MAREA link connects to Bilbao, Spain. The BRUSA link connects to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Both are south of the Atlantic Ocean Channel, but pass through the Dam Neck Ocean Disposal Site.14

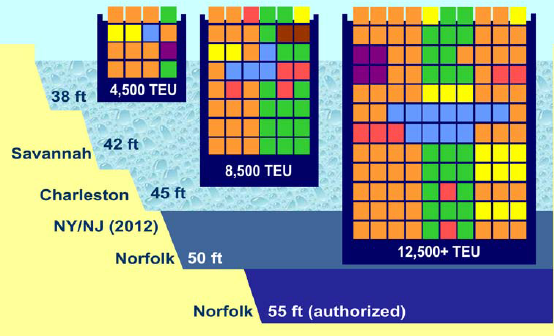

All ports know that Federal funding to deepen shipping channels could enhance or erode competitive advantages. The other two main competitors to the Port of Virginia, Charleston and Savannah, have their own plans to attract the largest container ships to the East Coast.

Charleston had obtained Federal funding to deepen its channel from 45-feet to 50-feet, but that was not enough for South Carolina. The state agreed to pay 100% of the extra cost required to dredge an extra two feet. Charleston plans for fully-loaded ships to have a 52' deep channel to move at low tides, as well as at high tides. The US Congress authorized the 52' channel in 2016.15

a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) of Hampton Roads reveals artificially-straight dredged ship channels, plus tunnels constructed underneath two channels for the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel linking Virginia Beach to the Eastern Shore

Source: South Atlantic Fishery Management Council, Essential Fish Habitat Viewer

Savannah, Georgia has a 23-mile channel from ocean to port. When the channel was deepened from 38 feet to 42 feet in 1994, the goal was to service ships carrying up to 4,000 TEU's. By 2013, ships calling at Savannah arrived with less than a full load. They could carry up to 8,100 TEU's, if the channel was 48-feet deep.

Savannah has received Federal approval to deepen the channel from 42 feet to 47 feet, with 60% funded by the Federal government and 40% by the Georgia Port Authority. All projects to deepen channels require arrangements for dredge spoil disposal, but each port has unique environmental mitigation requirements. Currents in a deeper-dredged Savannah River could result in oxygen-starved zones underwater, so that channel will not be dredged to the full depth of 48 feet as authorized by Congress. Georgia may have to build underwater oxygen bubblers to maintain a minimum level of 4 milligrams of oxygen per liter in the deeper channel.16

Getting Federal support to deepen shipping channels or upgrade on-shore infrastructure (such as rail/road connections) requires lobbyists in Washington, who advocate for staff to include specific language in authorization/appropriation legislation, then encourage Members of Congress to approve funding that benefits a specific port.

Representatives of all ports in serious competition for Federal funding must educate Congressional staff and members on the economic potential of port expansion - "if only Federal funding were provided to (...insert name of port here...), then (...insert what good things would happen there...)."

gantry cranes move containers from ships to chassis bodies on the wharves, and the chassis bodies are then moved to a location where containers can be loaded onto trucks or rail cars

Source: Virginia Port Authority, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Virginia Port Authority for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2014

The Virginia Port Authority has planned for expansion, particularly for processing containerized cargo from the supersized ships that started to arrive after widening of the Panama Canal. The port predicted that the number of containers to be processed would triple between 2015-2035.

Larger ships will bring more containers, and the Virginia Port Authority seeks to increase the number of visiting ships to more than 2,000/year. To handle the extra containers, capacity at the Norfolk International Terminal (NIT) and Virginia International Gateway (VIG) were doubled with new equipment.

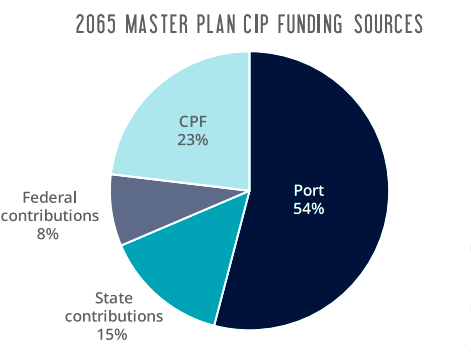

roughly half of the capital investments to expand capacity at the Port of Virginia will come from profits generated by the port's operations; 46% of the funding will be state/Federal subsidies (CPF = Commonwealth Port Fund, established by new transportation taxes in 1986)

Source: Port of Virginia 2065 Master Plan

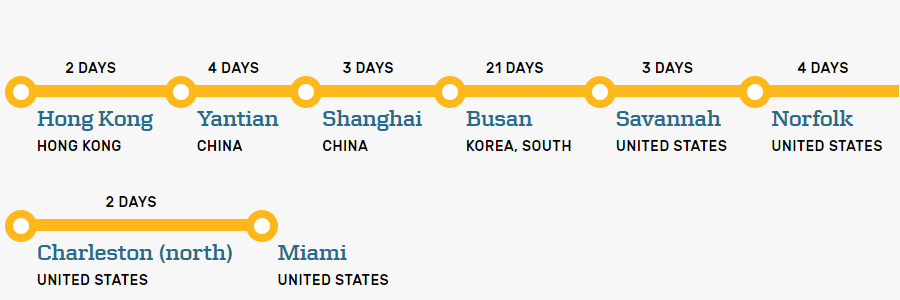

In 2016, the first ship with a 10,000 TEU capacity arrived at Norfolk International Terminal (NIT). In 2017 the COSCO Development, a 13,000 TEU ship, arrived at the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) terminal. That ship's routine stops included Hong Kong, Yantian, Ningbo, Shanghai, Panama, Virginia, Georgia and South Carolina.

the 2017 visit of the COSCO Development, with a 13,000 TEU capacity, demonstrated Norfolk could handle the largest container ships that could pass through the widened Panama Canal

Source: Virginia Port Authority, Biggest Vessel in Port's History Calls; Governor, Dignitaries Herald Arrival of 13,000-TEU COSCO Development

New York/New Jersey was not on the rotation in early 2017 because the project to raise the Bayonne Bridge had not been completed yet. Ships carrying more than 9,800 TEU could not enter the New York/New Jersey harbor until later in 2017, giving Virginia a head start in building trade relationships. Once the bridge was raised, the shipping line altered its sequence for ports of call for large vessels such as the COSCO Development. It made New York/New Jersey first, then Norfolk, Savannah, and finally Charleston.

Only a small portion of the cargo of the supersized container ships is offloaded in Hampton Roads. The COSCO Development was expected to transfer only 4,000 containers on its regular visits to Virginia International Gateway (VIG). Nonetheless, the executive director of the Virginia Port Authority said happily:17

By 2018, shippers had relied upon specialized container ships for 60 years. The largest container ship in the world could carry over 20,000 Twenty-Foot Equivalent Units (TEU's), and Virginia port officials were considering how to load/unload ships with a capacity of 16,000-18,000 TEU's.

Over the next 50 years, a consulting firm projected construction of significantly larger ships capable of carrying 50,000 TEU's. Such a size increase would require significant revision of gantries and infrastructure at a shipping terminal, and dredging even deeper channels through the Chesapeake Bay and Elizabeth River.18

container ships stop at a scheduled sequence of ports, loading/offloading only a percentage of their containers during each stop

Source: Maersk, TP16 Eastbound and National Ocean Service, Container Ship

The Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) could be designed from the beginning to accommodate larger ships. The Virginia Port Authority and the Corps of Engineers will continue the Craney Island Eastward Expansion project, so the terminal could be built when justified by demand for extra container processing capacity.

Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT) and Newport News Marine Terminal (NNMT) will be enhanced to process non-containerized cargo, including break-bulk operations (cargo not packaged in containers) and "roll on, roll off" cargo such as cars imported from Japan.19

the proposed Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) would add a fourth terminal for processing containers at Hampton Roads (Newport News handles primarily Ro-Ro and break-bulk cargo)

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk Harbor Navigation Improvements - Draft General Reevaluation Report and Environmental Assessment (Figure 3-1)

If the deepest water for containers ships was at Hampton Roads, then shipping companies could design their routes so the terminals in Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Newport News would be "first-in, last-out." Vessels importing the most containers would stop first in Virginia. Ships headed back to Europe, Asia, or elsewhere would get their last containers from a Port of Virginia terminal.

Many ships already follow that route design. Just having a deeper channel might not help the Port of Virginia compete if other ports also get deeper channels. Virginia and Georgia have chosen to partner in order to compete with New York/New Jersey and Charleston. The Georgia Ports Authority and the Virginia Port Authority created the East Coast Gateway Terminal Agreement in 2017 to coordinate the arrival of ships, so large customers such as Wal*Mart could maximize the efficiency of container distribution to warehouses along the East Coast.

tourists could see ships using the Thimble Shoal channel, until Island 1 was closed in 2017 for construction of a parallel tunnel

The Federal Maritime Commission approved the deal, claiming that exchange of information was intended to enhance supply chain logistics. Since the two ports could not set joint prices, the Federal agency concluded that the agreement did not create unfair competition for other ports.

In South Carolina, which in 2017 started building a second inland port at Dillon on I-95 comparable to the Virginia Inland Port at Front Royal, others saw the agreement as an effort to "crowd out" the port at Charleston. Consolidation in the maritime industry and Post-Panamax container vessels were predicted to reduce the number of ports visited by the larger ships, and the Virginia Port Authority chose to partner with Savannah rather than Charleston.

A fellow at the Brookings Institution commented in 2016 as the Delaware River channel was being deepened to 45 feet:20

A spokesperson for the Philadelphia Regional Port Authority, said at the time:21

Competition for Federal funding to deepen shipping channels is based on the claim that each port needs to dredge deeper in order to accommodate the bigger container ships. However, the COSCO Development required 44 feet or less when it visited Norfolk for the first time in 2017.

The original justification for a deeper channel in the Elizabeth and James rivers was the need to accommodate larger ships exporting Appalachian Plateau coal to foreign markets. Containers can be much lighter in weight than coal, so the need for a deeper channel for the Post-Panamax container vessels has been questioned.

The largest ships force port officials to convert Thimble Shoal Channel into a one-way channel. That delays traffic, but a key Port of Virginia argument is that a 55-foot channel is needed so Ultra-Large Container Vessels (ULCV's) can sail without waiting for the tide:22

the Port of Virginia is the beginning and the end of key roads and rail lines in Virginia

Source: 2015 Governor's Transportation Conference, Port of Virginia Final Video

New York/New Jersey attracts ships as a "first-in" site because its high population means many containers are directed to warehouses in that area. Savannah attracts ships because so many distribution centers for the southeastern US are clustered there. Congress is at risk of providing more funding than is required to meet shipping infrastructure needs Politics may end up directing Federal subsidies so one or more ports become "winners" with the deepest channels, while others are left behind.

Despite a 1994 state law prohibiting Virginia state agencies from hiring lobbyists, in 2013 it was revealed that the Virginia Port Authority was paying for such services. The state agency tasked its engineering contractor to perform advocacy to legislators, paying a 15% surcharge for the engineering contractor to make arrangements with a standard lobbying firm.

The Virginia Attorney General concluded the arrangement did not violate state law because it defined "lobbying" as efforts to influence state officials. The Virginia Port Authority was only trying to influence Federal officials. As the chair of the Virginia Port Authority stated:23

Savannah's channel was deepened in 1994 from 38' to 42' to service ships carrying 4,500 Twenty-foot Equivalent Units (TEU's), but Norfolk is targeting ships with three times that number

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, Draft 2013 Virginia Statewide Rail Plan (Figure ES-4)

The US Congress may choose to fund multiple channel deepening projects at multiple East Coast ports. Politicians from Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and New Jersey/New York desire for the Corps of Engineers to deepen channels to their ports. Multiple projects would increase costs and dilute the economic benefits, but funds for channel deepening could be decided by political calculus more than cost-benefit studies.

In addition to the advantages of marketing the "deepest port on the East Coast," the ego of regional leaders could also be a factor. As a Virginia Business article noted:24

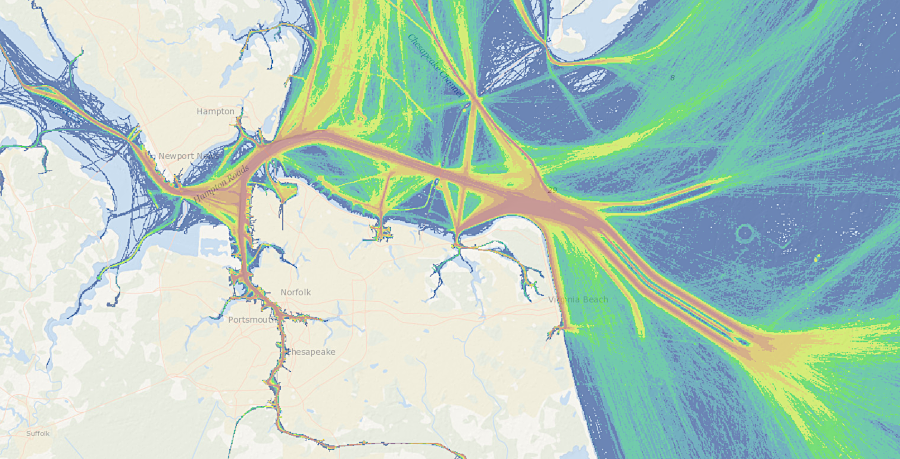

ship traffic through the Chesapeake Bay

Source: Mid-Atlantic Ocean Data Portal

In 2018, the Virginia General Assembly authorized $350 million in state funding (including $330 million in state-backed bonds) for deepening the channels to 55 feet and widening to 1,400 feet. However, the 2019-20 Federal budget proposed by President Trump included no funding for Norfolk, but did include proposed funding for the rival ports of Boston, Charleston, and Savannah. After the US Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in 2020, the FY22 annual work plan of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers included $70 million to repay some of the costs already incurred to dredge for a 55-foot deep channel.

Also in 2018, the US Army Corps of Engineers authorized deepening the Thimble Shoals channel to 55 feet, deepening other channels closer to the terminals to 55 feet, and dredging the Atlantic Channel offshore to 59 feet. The problem then became Federal funding, not Federal approval. Rep. Rob Wittman introduced legislation to provide $4 billion in funding for Virginia's port projects. However, the state committed to pay half of the total cost, and began spending its share, before getting any assurance that the US Congress would appropriate funding for the other 50%.

Using the $350 million in funding approved in the 2018 state budget, the Port of Virginia signed its first contract in 2019 to deepen the west side of the Thimble Shoal Channel from 50 to 55 feet, and to widen it to 1,400 feet. By 2024, the channels were expected to accommodate two, ultra-large container vessels simultaneously and minimize delays as they pass over the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel.

by dredging a deeper channel after 2019, ships requiring 55 feet of water depth could reach Port of Virginia terminals

Source: Port of Virginia, Dredging to Make Virginia the East Coast’s Deepest Port is Underway (December 2, 2019)

On December 15, 2019, dredging began at Thimble Shoals, west of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. A crane supporting a clamshell dredge scooped 21 cubic yards at a time from the bottom, and dumped the spoils into a barge for disposal in the Atlantic Ocean. Each barge trip carried the equivalent of 900 dump truck loads of spoils.

Clamshell digging was followed a year later by use of a trailing suction hopper dredge. After a tour on the ship, Governor Northam compared the suction dredging process to smoothly mowing grass.

Final completion of the project was delayed to 2025 and costs rose to $450 million, with the state and Federal governments splitting the costs 50% each. In 2024 the Thimble Shoals widening portion was completed. It allowed two ultra-large container vessels to pass at the same time. A spokesperson for the Port of Virginia described the impact succinctly:25

specialized hopper dredge ships maintain the depth and width of shipping channels in Hampton Roads

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 130423-A-ON889-015 (Bennett’s Creek dredging) and 130423-A-ON889-031 (Bennetts Creek dredging)

The COVID-19 pandemic led to a surge of imported goods from Asia. When shipping suddenly increased by 20%, Southern California ports were overwhelmed. At one point, there were 109 ships idling in th Pacific Ocean waiting for a berth.

Shippers adopted new routes to avoid the bottleneck and began sending more cargo to East Coast ports.

The successful expansion of the Port of Virginia facilities, including deepening the shipping channels, was demonstrated in May 2021. CMA CGM Marco Polo, the largest container ship ever to stop at East Coast ports at the time, visited the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) terminal in Portsmouth. That ship could carry the equivalent of 8,000 tractor trailer loads, over 16,000 Twenty-foot Equivalent Units (TEU's). Only a portion of that capacity was loaded/unloaded at the terminal in Virginia; the ship also stopped at port terminals in New Jersey, Charleston, and Savannah.

By the end of 2022, West Coast port officials and labor unions concluded that there would be permanent impacts, with Savannah and New York in particular capturing business that previously had gone to Long Beach and Los Angeles.26

On April 25, 2024, a groundbreaking ceremony started Atlantic Ocean Channel Phase II:27

groundbreaking for Phase II of the "Wider, Deeper, Safer" dredging project in 2024 involved throwing sand with shovels

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Breaking ground: U.S. Army Corps and Port of Virginia Spearhead Major Atlantic Ocean Channel Deepening (April 25, 2024)

The widening of Thimble Shoal Channel West to 1,400 feet started at the end of 2019 and was completed in March, 2024. Deepening the channel required two additional years. The final depth ended up being 55 feet. Biological impacts from dredging the shipping channel deeper at the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay were minimal because most benthic organisms lived in shallow waters, especially waters no more than six feet deep.

The Port of Virginia advertised that allowing two-way traffic through the channel, part of the $1.4 billion strategic infrastructure investment package, had reduced the stay of ultra-large container vessels (ULCVs) by 15%.28

widening Thimble Shoal Channel West to 1,400 feet made it more cost-effective for Panamax size container ships to do business at Port of Virgina terminals

Source: Captain J. William Cofer presentation to Virginia Port Authority, America's ULCV Gateway

The land-based infrastructure was expanded in parallel with widening and deepening the shipping channels. The Port of Virginia completed its fourth berth for ultra-large container vessels (ULCVs) in early 2026. Two were located at Virginia International Gateway. Two others were at Norfolk International Terminals, with a third such terminal planned for completion there in 2027.

An $83 million project to upgrade the central railyard at Norfolk International Terminals and add three new rail-mounted cranes was completed in 2024, expanding rail capacity there by 35%. At the Virginia Inland Port, railroad tracks were expanded in a $15 million project to handle larger trains. At the Richmond Marine Terminal, the capacity to load and unload barges was expanded.29

evolution of container ships - and future, post-Panamax size

Source: Captain J. William Cofer presentation to Virginia Port Authority, Virginia's Offshore Fairways (November 27, 2012)

after Hurricane Sandy in 2012, Rudee Inlet was dredged on an emergency basis to allow boats to access the marina

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 121110-A-ON889-041

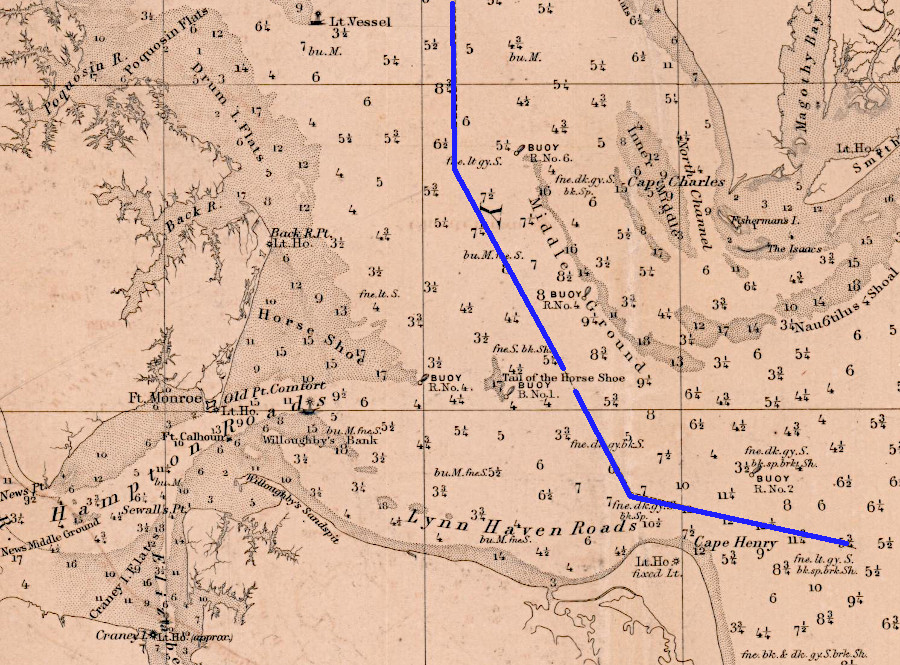

the shipping channel to Baltimore (blue line) passes between the Tail of the Horse Shoe shoal and Middle Ground shoal

Source: National Archives, Preliminary Chart of Delaware and Chesapeake Bays and the Sea Coast from Cape Henlopen to Cape Charles

the Norfolk Harbor and Channels Improvement Project ensures Norfolk offers the deepest shipping channel on the Atlantic Coast

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk Harbor deepening project advances with critical contract award