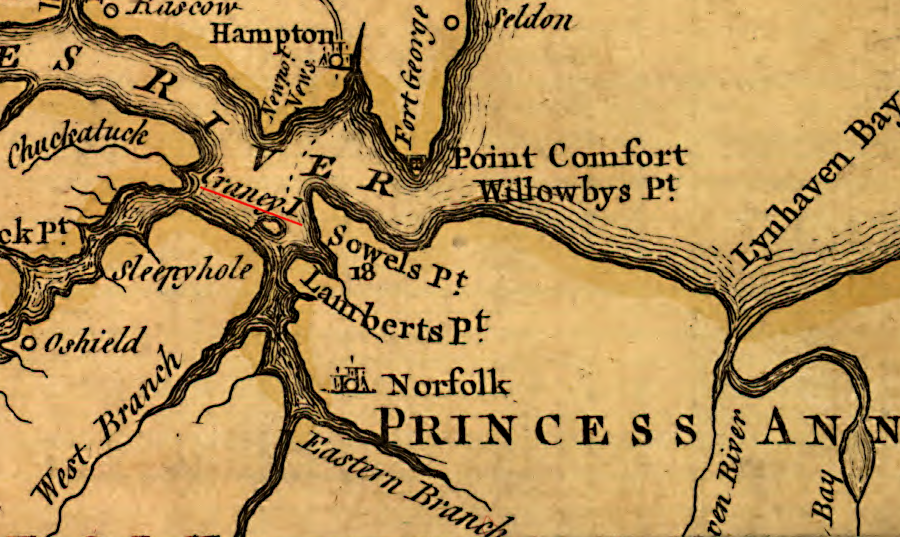

Craney Island in the 1750's

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1755)

Craney Island in the 1750's

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1755)

Craney Island was once separate from the western edge of the Elizabeth River. It was home to enough herons ("cranes") to justify its name.

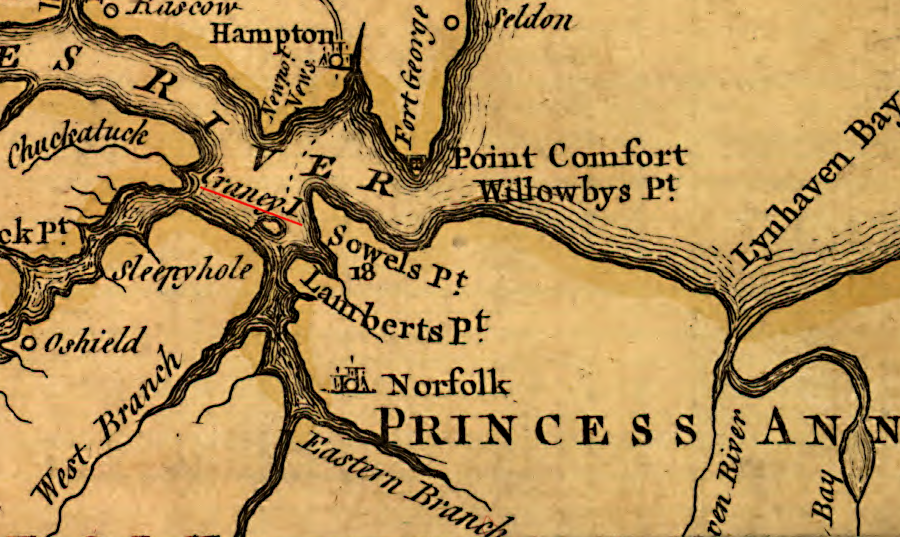

Craney Island, across the Elizabeth River from the coal-loading piers of the Norfolk and Western Railroad, was still an island connected to the mainland by a bridge in 1891

Source: Library of Congress, Bird's eye view of Norfolk, Portsmouth and Berkley, Norfolk Co., Va

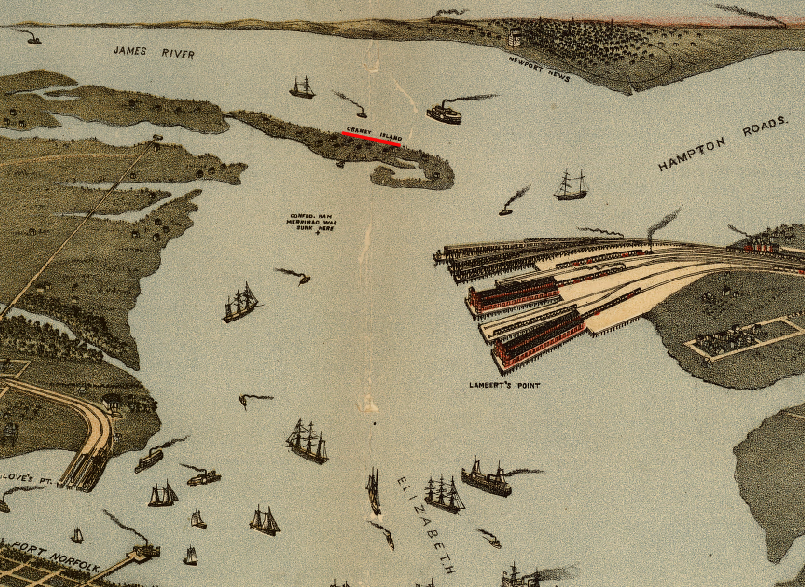

Today, the island is a dredge spoil site and connected to the mainland. Silt/clay/sand is excavated from the bottom of the Elizabeth River and Hampton Roads to maintain the depth of the shipping channels ("dredge spoils"), then barged or pumped to Craney Island.

It serves as a disposal site for more than dredge spoils. A humpback whale carcass that appeared in Hampton Roads in 2017 was dragged onto Craney Island, to eliminate any possibility of a ship hitting it. The site was sufficiently isolated that decomposition did not inconvenience local residents.1

Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area was used as the disposal site for a dead humpback whale in 2017

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, IMG_9565_BJ794

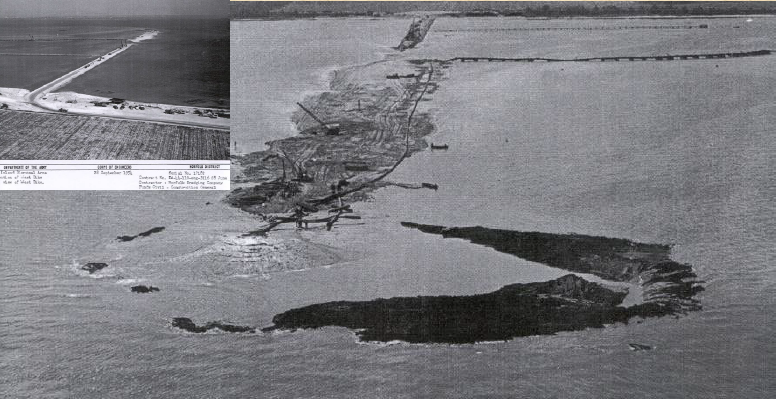

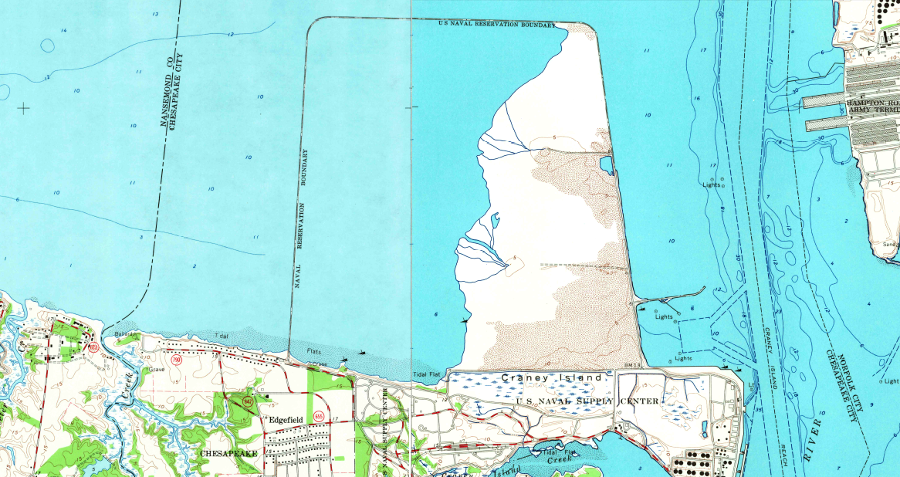

Since World War II, the original appearance of Craney Island has changed dramatically. In 1938, the Thoroughfare (a channel separating Craney Island from the mainland) was filled in and Craney Island became a part of the mainland. Starting in the 1950's, the US Army Corps of Engineers surrounded the site of the original island with dikes, creating what is now the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area (CIDMMA).

initial construction of Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area containment dike in 1950's

Source: Virginia Port Authority, Management of Dredged Materials: Challenges and Opportunities

in 1954, the Corps of Engineers began to enclose Craney Island with dikes to create a 2,500 acre dredge disposal site

Source: Aaron L. Zdinak, Characterization Of Soft Clay - a Case Study At Craney Island (slide 8)

When first completed in 1957, the 2,500-acre Craney Island disposal site was expected to receive 96 million cubic yards of sediments dredged from the Elizabeth River and Hampton Roads shipping channels and be filled by 1979. By 2004, the facility had received 225 million cubic yards of dredged material, thanks to various techniques to increase capacity, and still had decades of useful life remaining.

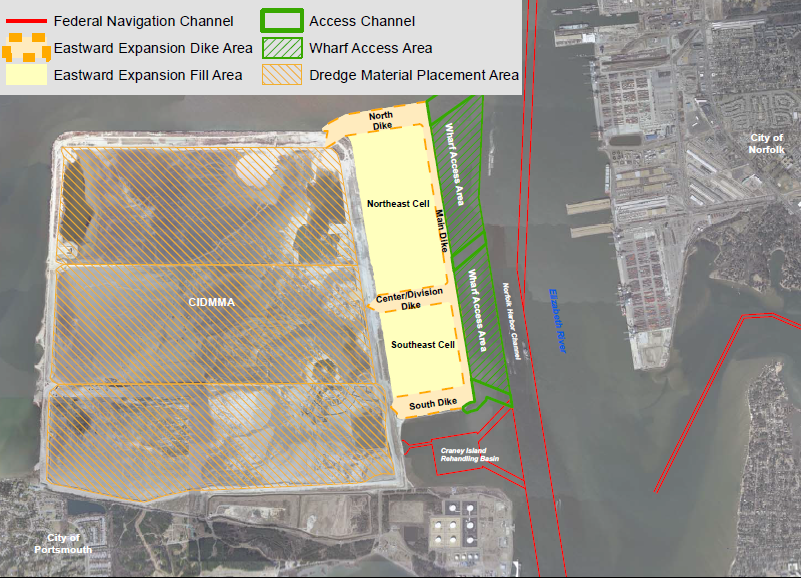

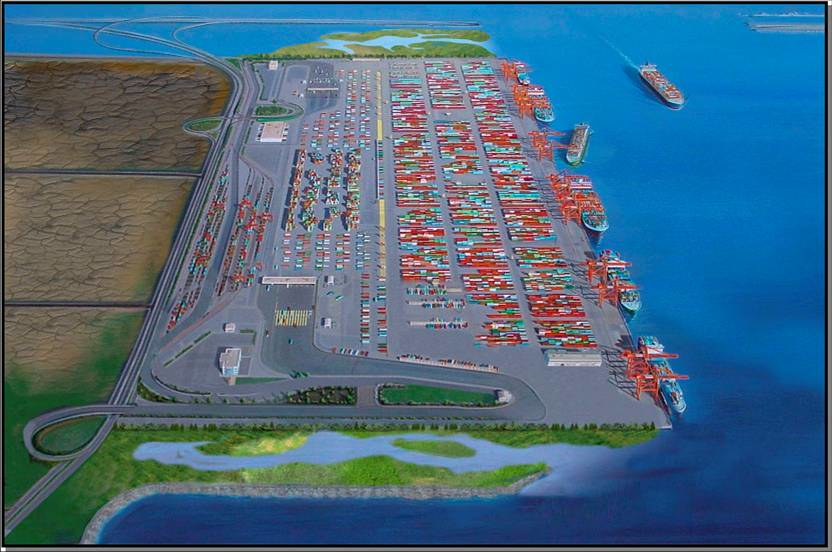

The last planned expansion, adding 580 acres on the eastern edge, is now underway. The Virginia Port Authority plans to construct the new Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) on the top of the expansion, providing a 20% increase to the ports capacity (handling 19 more vessel calls per week).

Craney Island eastward expansion plan

Source: National Marine Fisheries Service, Maintenance of Chesapeake Bay Entrance Channels and use of sand borrow areas for beach nourishment

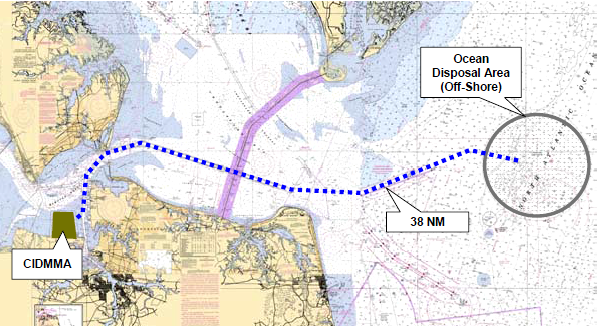

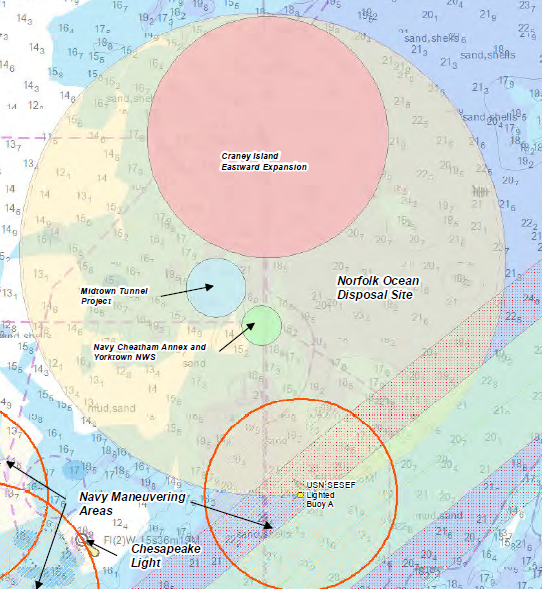

When Craney Island is completely filled in 2028, it will be a 47' tall mound. Unless the west dike is strengthened to add another 15 years of capacity, after 2028 dredge spoils from the Elizabeth River/Hampton Roads now deposited at Craney Island will be barged to the Norfolk Ocean Disposal Site 17 miles offshore in the Atlantic Ocean.2

after Craney Island is full, sediments dredged from Hampton Roads will be deposited in the Norfolk Ocean Disposal Site (NODS)

Source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and The Virginia Port Authority, Dredged Material Management Plan For Craney Island Eastward Expansion and Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area

Initially, submerged land next to Craney Island was used as a spoils dump site; no containment dikes were constructed. Between 1917-1927, the US Congress authorized dredging a 40' deep channel to the ports on the Elizabeth River. Large amounts of material dredged to maintain river channel depth were deposited near Craney Island between 1920-39. That initial disposal was uncontained, and sediments could wash back into the Elizabeth River channel over time.

The River and Harbor Act of 1946 authorized construction of a contained dredge disposal site at Craney Island. Between 1954-57, the US Army Corps of Engineers constructed confining dikes to enclose 2,500 acres at the Craney Island Disposal Area, now known as the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area (CIDMMA). The site was authorized to receive material excavated in association with navigation projects, primarily deepening and maintaining shipping channels. As a navigation project, Craney Island is does not accept construction and demolition debris from inland construction projects (except for road and railroad construction).

in 1965, dredge spoil had filled about 1/3 of the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Newport News South 7.5x7.5 topographic map (1964) and Norfolk North 7.5x7.5 topographic map (1965)

Dredging sediments from shipping channels and anchorages, barging/pumping the "spoils" to Craney Island, and depositing them inside the containment dikes requires powerful machinery. Dredge spoils are pumped over the eastern dike and the heavy sand particles accumulate there. Smaller particles of clay are carried further west. The water in the pumped material finally exits the containment cell through spillboxes in the western dike.

The dikes are constructed of sand, not from the clay-rich scraped up from the river channels. The Corps excavates sand that migrates into the channel, or that accumulates on the eastern side of the Craney Island containment cell, and uses it to raise the height of containment dikes.

hopper ships like the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredge Currituck carry dredge spoils to the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area and to beach replenishment sites

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Rudee Inlet Dredging - 1, , 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7

A reporter from The Virginian-Pilot described how the sediments are contained:3

sediments are pumped into the east side of Craney Island, and flow for two-four days before water escapes on the western side

Source: Virginia Port Authority, Management of Dredged Materials: Challenges and Opportunities

dredge spoils are pumped into the cells on the east side, then water drains to the exit weirs in the dike on the west side

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), The National Map

In the 1950's, the projected life of the facility was 20 years before it would be full. It was clear in the 1970's that expansion, or a new location, was necessary. By 1980, the 130 million cubic yards of fill had created a surface extending 15 feet above mean low water. The site had received 35% more than the anticipated capacity, thanks to unpredicted settling of the marine clay due to the weight of the heavy dredge spoils.

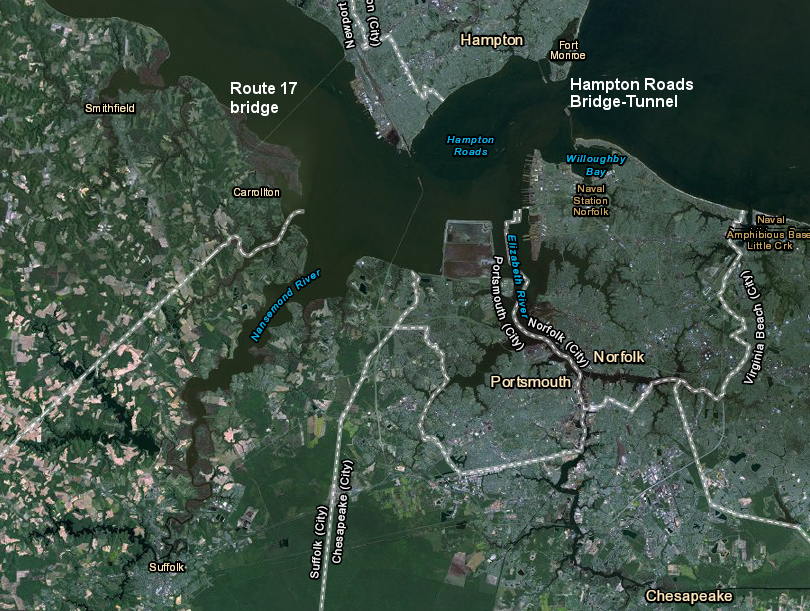

Craney Island accepts dredged materials from the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel on the west to the James River Bridge on the north, and the entire Elizabeth and Nansemond Rivers

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Initially, the entire 2,500-acre area within the containment dikes stayed wet as new dredge spoils were constantly added. That limited compaction. To increase ultimate capacity, internal dikes at Craney Island were constructed to create three cells in the 1980's.

Sediments were pumped into each cell on a three-year cycle. The three-cell arrangement allowed sediments in each cell to dry out and compact for two years, as particles of different sizes realigned in a process described as "selfweight consolidation" and as underlying clay soils were compressed.

the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area is divided into three cells

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Bridges and Culverts

The dikes were also raised to 30' in height to extend the disposal site's projected life. However, in 1989 the US Army Corps of Engineers predicted Craney Island would run out of space for new dredge spoils within a decade.

The Corps considered alternatives other than just expanding capacity at Craney Island. Disposal of dredged materials in the open ocean had begun in the 1950's. The Dam Neck Ocean Disposal Site was created when the Thimble Shoals Channel was deepened to 45' in the 1960's.

After the Water Resources Development Act of 1986 authorized dredging a 60' Atlantic Ocean Channel and deepening the Thimble Shoals Channel, Newport News Channel, and Norfolk Harbor Channel (to Lamberts Point) to 55', the search for cost-effective dredge disposal sites expanded. The sands removed from the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean Channel and the Thimble Shoals Channel were suitable for recycling as beach replenishment material, but the muddy sediments from the Elizabeth River are not suitable for that use.

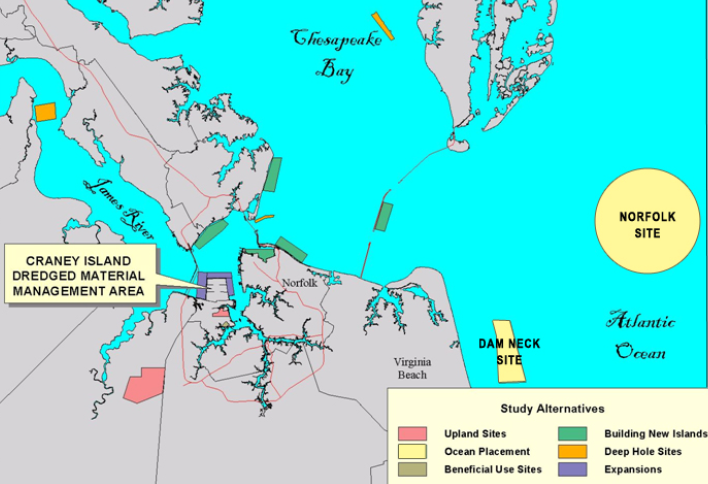

alternative locations considered for disposal of dredged sediments, in addition to expanding site at Craney

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Craney Island Eastward Expansion Feasibility Study (slide 17)

Other options included spreading a thin layer of sediment on the bottom next to Trimble Shoals Channel or building new artificial islands at Willoughby Bay, Hampton Flats, or Ragged Island. Sites further away that received serious consideration for new containment cells included the Horseshoe Shoal area off Buckroe Beach, Willoughby Spit/Ocean View (which received material dredged from Pier 12 at the Norfolk Naval Base in 1985), and eastward of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. Inland, the Corps looked at disposal in Dismal Swamp, trucking dredge spoils to former gravel mining pits, or using trains to carry material to sites further inland.4

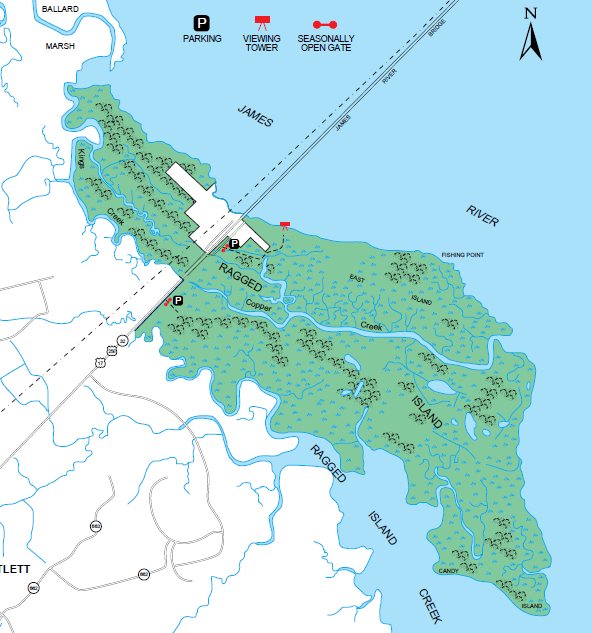

Ragged Island, at the south end of the Route 17 bridge over the James River, is a state Wildlife Management Area where islands created from dredge spoils could increase habitat and reduce the high natural erosion rates

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Ragged Island WMA

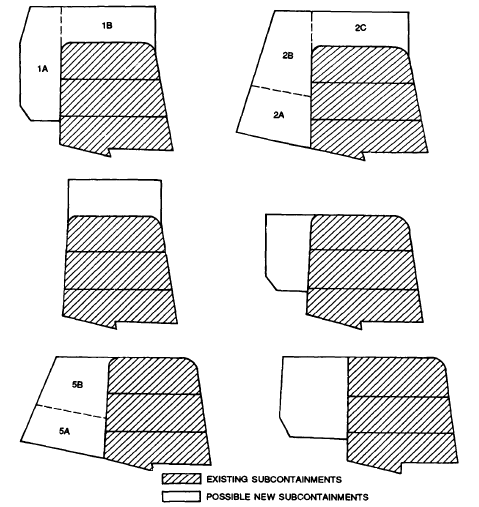

In 1989, the Corps of Engineers identified six alternatives for expanding the Craney Island site, which it considered to be the most cost-effective location for disposal:5

six options to expand Craney Island, proposed by the Corps of Engineers in 1989

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Storage Capacity Evaluation For Craney Island Expansion Alternatives (Figure 3)

The Corps' proposal to expand Craney Island ran into intense local opposition from residents who lived on the western side of the site. Owners of high-value homes with water views, and city officials in Suffolk and Portsmouth with plans for new waterfront development that would generate tax revenue, realized that vistas would be blocked by a 34' high mud mountain extending almost to the I-664 Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel.6

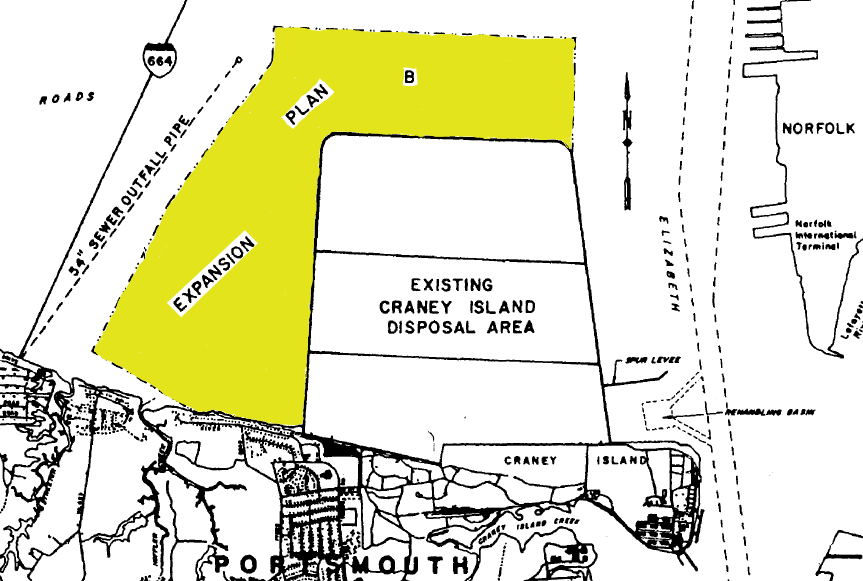

the proposal to expand Craney Island to the west triggered opposition from residents in Portsmouth and Suffolk with waterfront views

Source: House Document No. 16, Beneficial Uses of Dredged Materials in Hampton Roads, Virginia (1993)

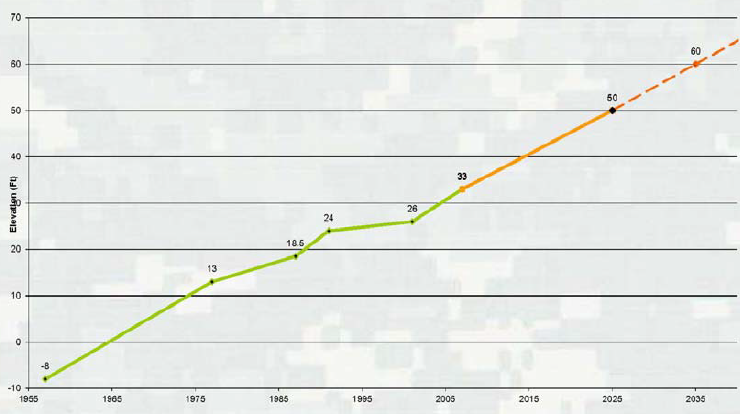

In response, the General Assembly of Virginia passed a law in 1991 banning use of state resources - including state-owned submerged land - for westward expansion. To expand the dredge spoil pile "up" rather than "out," in 1995-2001 the Corps installed strip drains that allowed water trapped in subterranean clay to escape. The dewatered clay provided a solid foundation that allowed the Corps to build bigger dikes up to 47' high. If the dike on the far western edge of the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area was strengthened with a 150-foot wide berm, then dredge spoils could reach 60' in height.7

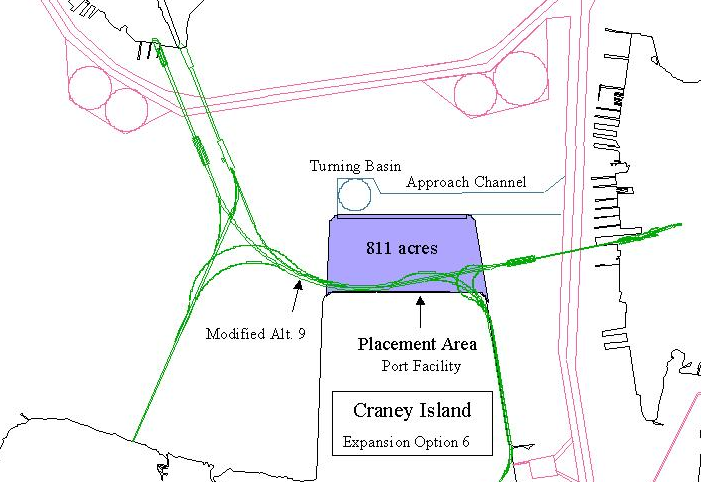

The Virginia Port Authority encouraged the Corps of Engineers to expand the Craney Island eastward, thus avoiding the conflict with Suffolk and Portsmouth landowners on the west side. Instead of limiting navigation, an expansion into the Elizabeth River offered the unique opportunity to create a new terminal for container ships, which the state port agency had identified as a critical need by 2018.

Craney Island Eastward Expansion, as pictured in 2014

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 140617-A-CE999-001

In 2003, the commander of the US Army Corps of Engineers Norfolk District suspended the feasibility study for expanding Craney Island to the east, after determining the environmental impacts would be excessive. In 2004, a new commander re-opened the study. The Environmental Impact Statement was completed in 2006.

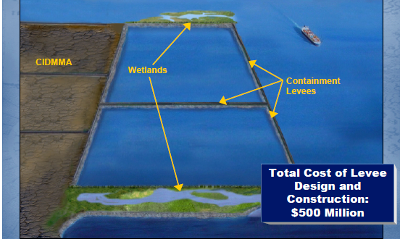

The Federal agency supported creation of a 580-acre addition on the east side, accommodating three more years of dredge spoil (later increased to nine years). After a 220-acre expansion cell was completed, the Port of Virginia could construct the first phase of a new shipping terminal by 2017. Filling a 360-acre cell to the north would finish the extension project and allow expansion of the terminal.

The Corps of Engineers preferred but did not recommend the primary alternative, which also included reinforcing the dike on the west side. Opposition by state and local officials blocked that alternative. The Corps endorsed the Locally Preferred Plan with no alterations on the west side, but noted that west dike reinforcement was not needed until 2028 so that option could be reconsidered later.

The Corps also concluded that Virginia would have to pay 96% of the costs of the eastward expansion (rather than split the costs 50-50). The state was always expected to be responsible for 100% of the Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) construction costs.8

on June 6, 2012, the Executive Director of the Virginia Port Authority and the District Engineer of the Corps of Engineers agreed on how the Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) would be developed

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers (YouTube channel), District, Port Authority Agree on Craney

The potential impact on Virginia's economy of creating a new terminal on Craney Island was briefly a factor in the 2006 US Senate election. Incumbent Sen. George Allen, in a debate with Democratic challenger Jim Webb, asked "what's your position on the proper use of Craney Island? Webb, a former Secretary of the Navy, responded ""I'm not sure where Craney Island is. Why don't you tell me?, and Sen. Allen snapped "Craney Island's in Virginia."

Sen. Allen's partisans claimed that exchange exposed Webb's ignorance about a key issue in vote-rich Hampton Roads. Webb's defenders claimed his response reflected only that the question was posed without any context. A leading political analyst concluded that Webb's comment would not affect the outcome of the race:9

The Water Resources Development Act of 2007 formally authorized the Craney Island Eastward Expansion project. Senator Webb knew about it then, and he voted in favor.

interior dikes separating Craney Island into three cells (constructed 1984) are raised in height, as the mound of sediments grows

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Newport News South 7.5x7.5 topographic map (2013) and Norfolk North 7.5x7.5 topographic map (2013)

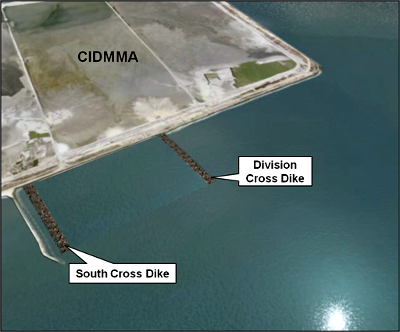

New dikes for the expansion on the east side are made of sand; building a bulkhead of steel sheet piles or concrete would have been far more expensive. The Corps considered constructing those dikes from material dredged when creating the 50-foot deep access channel in the Elizabeth River to the new Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT), but those river sediments included too much clay.

spreading some of the first sand to create the new containment cells on the east side of the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area

Source: Virginia Port Authority, Work on Dike Foundations for Craney Island Underway

The top layer of dredged Elizabeth River sediments excavated for construction of the new channel to the proposed new terminal at Craney Island were deposited in the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area. That top layer was presumed to be contaminated with toxic wastes from creosote plants and industrial operations upstream. The remaining clay-rich sediments from deeper in the channel were considered to be low risk and barged to the Norfolk Ocean Disposal Site (NODS).

at the Norfolk Ocean Disposal Site, a specific zone is reserved for dredge spoils from eastward expansion of Craney Island

Source: Army Corps of Engineers, Marine Features in the Vicinity of the Atlantic Ocean Channel

At the site of the new dikes on the eastern side of the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area, overlying sediments of the Norfolk Formation were excavated to reach the sandier (and more-stable) Lower Norfolk Formation and the Yorktown Formation. Dikes were then constructed from sand barged in from the Atlantic Ocean Channel and Thimble Shoal Channel, which are dredged regularly to maintain channel depths.

Once the new dikes made from recycled sand were above water level, sand from Craney Island was added. That beneficial use moved sand which had already been deposited in a cell of the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area to the dike, and created more space inside the cell. That process extended the life of the spoils disposal site for another six years, turned "river bottom to island top," and helped to create "the world's biggest man-made sandbox."10

building the south and division cross dikes for the eastward expansion

Source: Craney Island Eastward Expansion

The height of Craney Island will continue to grow as various shipping channels in the Elizabeth River and Chesapeake Bay are deepened/maintained and dredged materials are deposited behind the dikes. Further up the Chesapeake Bay, the Corps has constructed a similar facility at Poplar Island for deposition of material dredged from the shipping channels into Baltimore Harbor.

Poplar Island will be expanded by dumping dredged material into multiple cells. When the Poplar Island cells are filled around the year 2030, James and Barren islands will be expanded. As part of the Mid-Chesapeake Bay Island Ecosystem Restoration project, James Island will grow by 2,100 acres and Barren Island will grow by 72 acres. That will offset a small amount of the 10,500 acres of island habitat on the last 150 years.11

Poplar Island dredge disposal project, used for the Port of Baltimore, is similar to Craney Island

Source: Maryland Environmental Service, About Poplar Island

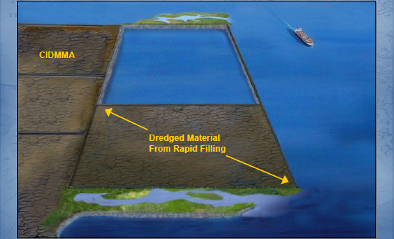

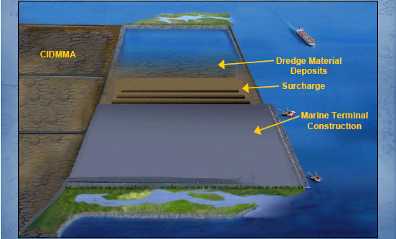

Craney Island is built on soft sediments, and is sinking. The eastward extension is designed to sink 20', more than the height of a two-story building.

The new cells are designed to support the 580-acre marine terminal for processing cargo containers, the Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT). The Port of Virginia does not want subsidence that could result in cracking pavement or tilting cranes.

To establish a stable surface, the new cell will be overloaded temporarily with a pile of sediments up to 30' high. After about a year of compressing the layers below, the pile of temporary sediments will be removed so the terminal can be constructed on a base of packed, more-stable sediments.12

Step 1 and Step 2 for eastward expansion of Craney Island

Source: Virginia Port Authority, Craney Island Feasibility Study Update (Slide 5 and Slide 6)

Step 3 and Step 4 for eastward expansion of Craney Island

Source: Virginia Port Authority, Craney Island Feasibility Study Update (Slide 7 and Slide 8)

Eastward Expansion of Craney Island - proposed "build out" (completion) in 2032

Source: Virginia Port Authority, Craney Island Feasibility Study Update (slide 9)

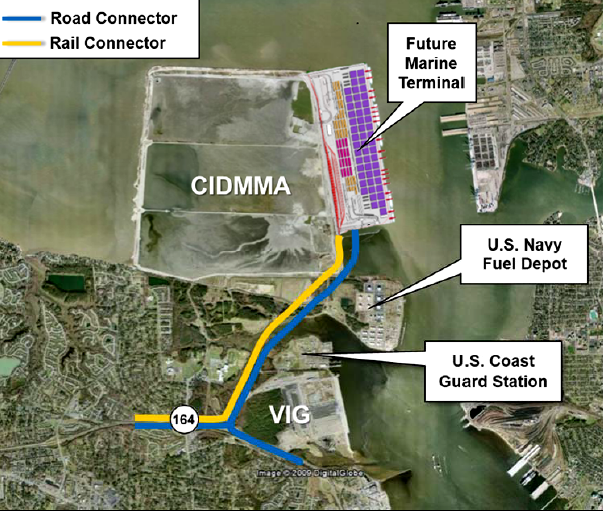

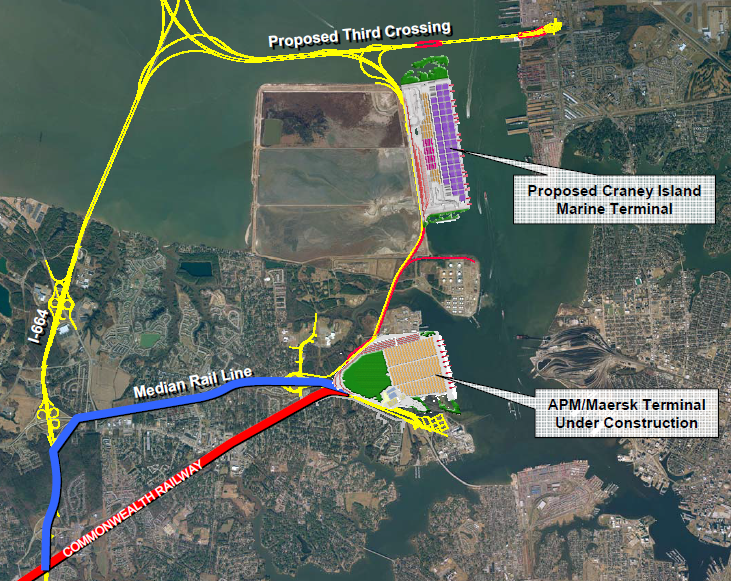

The proposed Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) will include a road and rail connection to the Western Freeway (VA 164) on the south. The Commonwealth Railway will carry containers to either Norfolk Southern or CSX, both of which offer service already at the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) terminal. The Western Freeway will provide access for trucks to I-664, which will allow trucks to reach I-64 on the north (via the Monitor-Merrimac Bridge-Tunnel) or US 58/460 on the south.

containers will be transported in and out of the new terminal by both truck and the Commonwealth Railway

Source: Virginia Office of Intermodal Planning and Investment, Master Rail Plan for the Port of Virginia (Figure 5)

Norfolk Southern can utilize the Heartland Corridor to transport containers from Hampton Roads to the Midwest, via Roanoke. Traffic going north beyond Alexandria, or south through North Carolina, can use the CSX.

The Port of Virginia predicts 50% of the containers at Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) will be transported by rail, requiring up to eight trains to carry 2,800 containers/day. In 2013, rail transported 34% of the port's container traffic, up from 25% in 2007.13

The proposed Patriots Crossing bridge-tunnel, designed to link Norfolk to the I-664 Monitor-Merrimac Bridge-Tunnel, would facilitate truck traffic. Patriots Crossing would be built north of the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area and the new terminal. If actually completed, trucks with double-stacked containers could drive via that "third crossing" to I-664, then north to I-64 and west to the Interstate 95 corridor.

shippers using Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) would have rail access to CSX/Norfolk Southern via the Commonwealth Railway (now using new tracks relocated to the highway median) as well as truck access to I-664 via the Western Freeway - and potential a Third Crossing option

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, On-dock Rail Subcommittee Report (April 3, 2007)

The Corps of Engineers justified expansion of the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area in 2006 based on a need for increased cargo-handling capacity in Hampton Roads. In 2010, the Virginia Port Authority leased the APM Terminal (APM) in Portsmouth for 20 years.

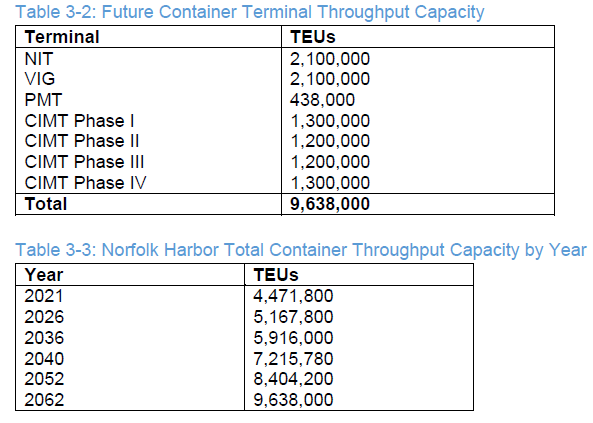

The state defined a new timeline to complete the Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT). Phase 1 would be finished in 2028, before the lease of the APM Terminal (APM) was supposed to expire, and construction of Phase II would be completed in 2039. Phase II would expand capacity from 3.5 million TEU's (Twenty-foot Equivalent Units) to 9.65 million TEU's.14

sanctuary oyster reefs were constructed in the Lafayette River as mitigation for the Craney Island Eastward Expansion project

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District Image Gallery

In 2012, as Virginia again considered privatizing its shipping terminals, the Corps of Engineers re-analyzed the proposed Federal investment in the Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) project.

The Panama Canal, before widening, had been limited to ships that could load 13 containers wide on the deck. The re-analysis assumed use of the larger Suez-class cranes that can stretch across ships loaded 22 containers-wide, stacked six containers high. The Corps concluded that the benefit-cost ratio of the Craney Island Marine Terminal over the next 50 years would be better than 6:1, almost double the Federal government's initial estimates.15

Studies and plans are projections that may come true in the long run, but the Virginia Port Authority business conditions in 2012 were not optimistic. Starting with the 2008 recession, the Virginia Port Authority lost money for five years in a row.

During debates over privatizing the state-owned facilities, the Virginia International Terminals (VIT) had offered steep discounts to pump up the volume of traffic and deter state officials from selling the terminals. The discounts attracted so much business that most workers were earning overtime pay. As a result, the extra revenue was below the costs to handle the extra containers.16

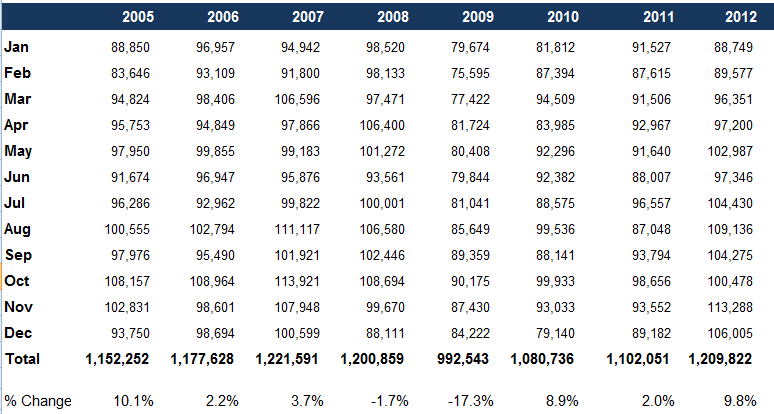

general economic conditions, such as the recession starting in 2008, affect the number of containers processed by the Port of Virginia

Source: Virginia Port Authority, VPA General Statistics

Plans to build a new terminal on Craney Island slowed down after Governor McAuliffe was elected to replace Governor McDonnell in 2013. The new governor retained key state transportation leaders, but they shifted their strategy for increasing capacity to process containers at the Virginia Port Authority terminals. In 2014, after completing return-on-investment calculations, Virginia officials chose to expand the existing Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT) rather than speed up construction at the new Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT).

Governor McAuliffe also chose to negotiate an extension of the state's 20-year lease of APM Terminal (APM), which in 2014 was renamed the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) after the A. P. Moller-Maersk Group sold its ownership to a British pension fund.

The governor signed an extension of the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) lease to the year 2065. The extra time justified the state spending $300 million for new equipment at that terminal. The General Assembly also approved $350 million to increase the capacity to process containers at Norfolk International Terminal (NIT).

Once the state signed its long-term lease to use Virginia International Gateway (VIG), the pressure evaporated to complete a new Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT). The completion deadline of 2028 would have allowed the Virginia Port Authority to use a new terminal two years before the lease of the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) expired. The lease extension until 2065 altered the urgency for building a separate terminal, in four stages on Craney Island, to double the capacity of the Port of Virginia to handle containers.17

the Port of Virginia still anticipates it will need to build the Craney Island Marine Terminal (CIMT) to handle increasing container volume

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk Harbor Navigation Improvements - Draft General Reevaluation Report and Environmental Assessment (Table 3-2, Table 3-3)

expanding Craney Island to the north would have required constructing the third harbor crossing so traffic did not conflict with terminal operations

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Hydrodynamic Model Study, Eastward Expansion of Craney Island

orange line represents 2007-2025 elevation of Craney Island; orange dashed line represents potential future elevation after 2025

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area (CIDMMA) Operations and Maintenance Project (August 6, 2012)

sediments dredged from Hampton Roads shipping channels are stockpiled on Craney Island

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District Image Gallery

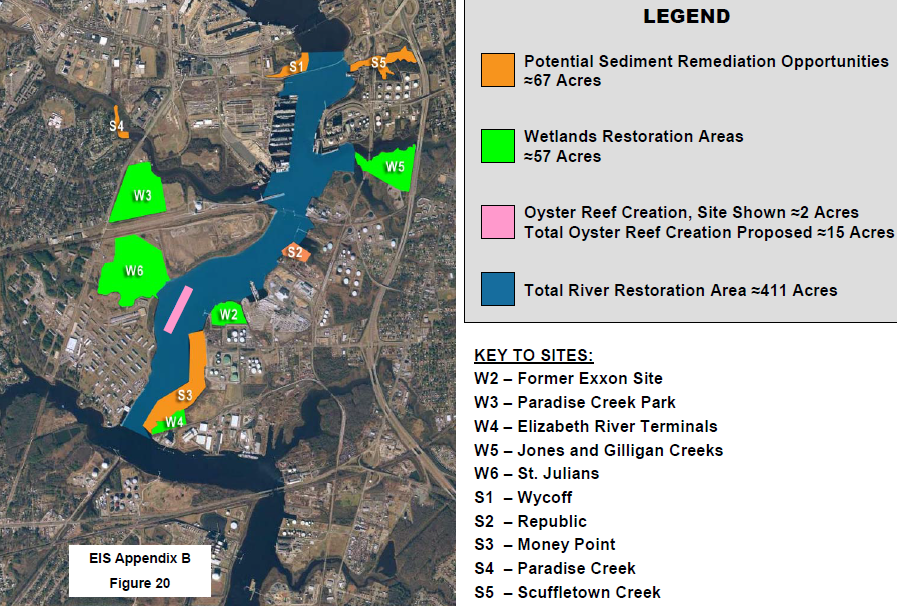

mitigation of impacts on submerged bottomland and open water habitat by the Craney Island project included restoring wetlands and creating oyster reefs in the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River, near the Norfolk Navy Shipyard

Source: Craney Island Final Environmental Impact Statement, Appendix B - Mitigation Analysis (Figure 20)