the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, looking towards Hampton

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Expansion Project, DBE/SWaM Opportunity Event (September 11, 2019)

the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, looking towards Hampton

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Expansion Project, DBE/SWaM Opportunity Event (September 11, 2019)

The highway was extended from Hampton to Norfolk by constructing a combination bridge and tunnel. Two artificial islands were built to anchor the tunnels, which were needed to ensure the shipping channel would never be blocked by an enemy country or terrorists destroying a bridge.

The two-lane Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel opened in 1957. A two-lane set of parallel spans with a new tunnel was completed in 1976. The original two-lane tunnel was then dedicated for just westbound traffic.

The sand for expanding South Island in 1976 was dredged from Willoughby Bank, a shoal east of the island. Later construction in 2021 revealed that the sand included Civil War-era cannonballs. They were treated as live ordinance until military explosive experts declared each one to be safe.1

After years of political disputes, regional leaders finally agreed that doubling the capacity of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel was the #1 transportation priority. Other alternatives considered included expanding the Monitor-Merrimac Bridge-Tunnel (I-664) and building a new bridge-tunnel north of Craney Island to connect I-664 to I-564.

Alternative C would have built a new bridge tunnel west of I-564, plus expanded the Monitor-Merrimac Bridge-Tunnel

Source: Hampton Roads Crossing Study, Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (p.2-32)

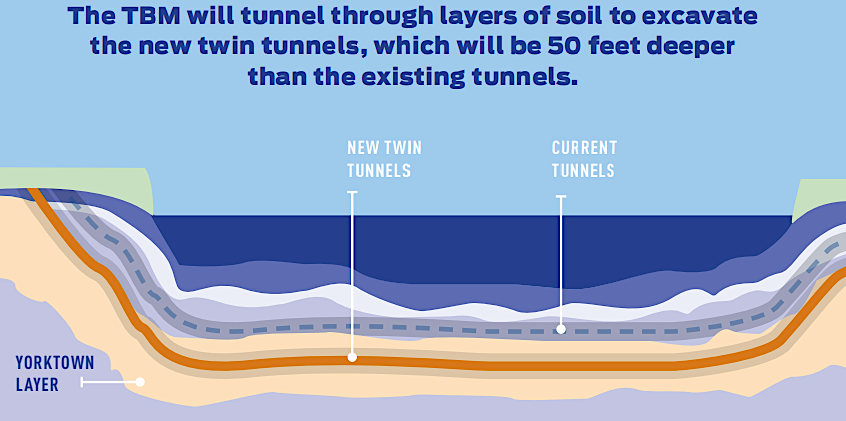

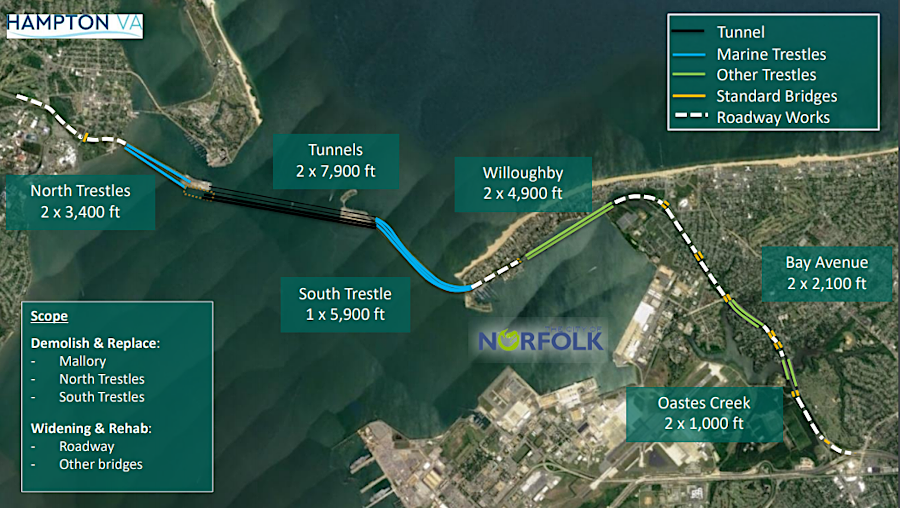

Two new tunnels were constructed upstream of the current tunnels, and placed 50 feet deeper, to reduce existing delays and accommodate growth beyond the existing 100,000 vehicles/day in the summer. All existing bridge spans above the water were replaced, while the existing underground tunnels were retained.

the two new tunnels excavated by a tunnel boring machine (TBM) were deeper than tunnels excavated by trenching in 1957 and 1976

Source: HRBT Expansion Magazine, Excavating Twin Tunnels Is Anything But Boring (May, 2020)

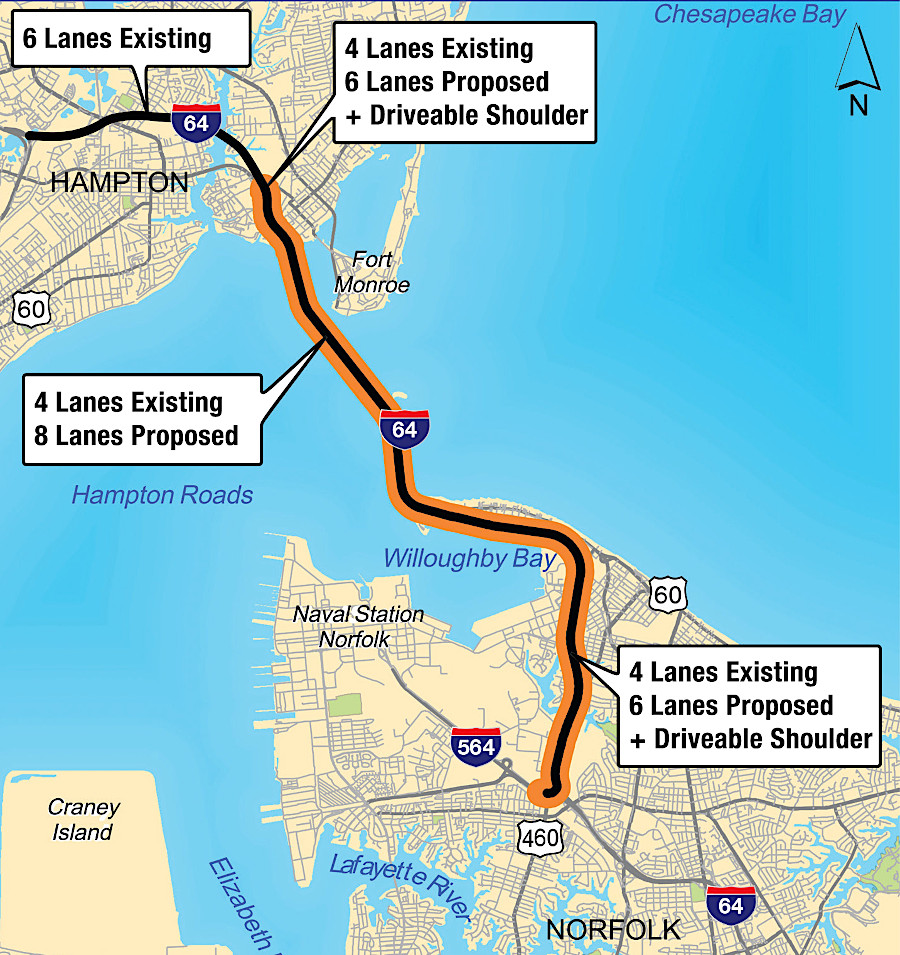

In addition, a third lane plus a drivable shoulder was added in each direction on I-64. On the north end of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, widening was extended up to Settlers Landing Road in Hampton. On the south end in Norfolk, widening reached the I-564 interchange. In an emergency, vehicles should be able to use four lanes of traffic in each direction between Norfolk-Hampton. If the eastbound I-64 lanes are reversed for hurricane evacuation, vehicles were expected to use eight lanes going north to Hampton.

the final decision to expand the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel created an 8-lane tunnel with initially 6-lane connections on north and south ends

Source: HRBT Expansion Project, map of the project location

The funding challenge was solved when the General Assembly authorized special regional gas and sales taxes, to be managed by the Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission (HRTAC). The taxes, paid primarily by local residents, were intended to generate 95% of the $3.8 billion required for the project. Only $309 million came from state funding allocated by the Commonwealth Transportation Board, such as SmartScale.

The expansion to eight lanes, above and below water, was the largest construction project in the history of the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT). Completion was predicted initially in 2025, but in 2024 the deadline was extended 18 months into 2027. The contract included an incentive for the contractor, Hampton Roads Connector Partners, to meet a "substantial completion" date that allowed for the general public to drive vehicles through the tunnel. If the project was substantially complete in September 2026, the incentive payment was $90 million.2

drivers go underneath the shipping channel, using the tunnel portion of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation

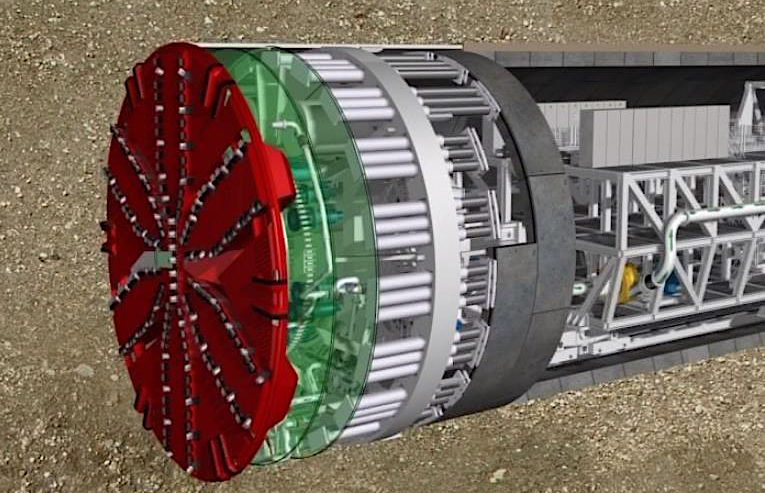

The contractor chose to use a tunnel boring machine (TBM) to excavate the sediments and create tubes 44.5' in diameter. That created a need for 21,000 precast concrete segments, with nine segments assembled to create each ring as the machine inched forward.

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, HRBT: How a Tunnel-Boring Machine (TBM) Operates

The winning bidder to supply the concrete segments was Coastal Precast Systems, located at Cape Charles in Northampton County. In 2019 the company purchased the site of the former Bayshore Concrete Product Corporation, which had been created in 1961 to provide precast concrete for the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. After losing a bid for the expansion of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, Bayshore Concrete closed down in 2018.

Together with Technopref Industries, Coastal Precast Systems produced and barged 18 rings at a time to South Island.3

The "big dig" for the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel was just the fourth project in the United States planning to use a tunnel boring machine. In addition to tunnels in Seattle and Miami, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel chose to construct two new tunnels across the channel at Thimble Shoal using the same excavation technology. The new bored tunnel for the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel was planned for completion after the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel.

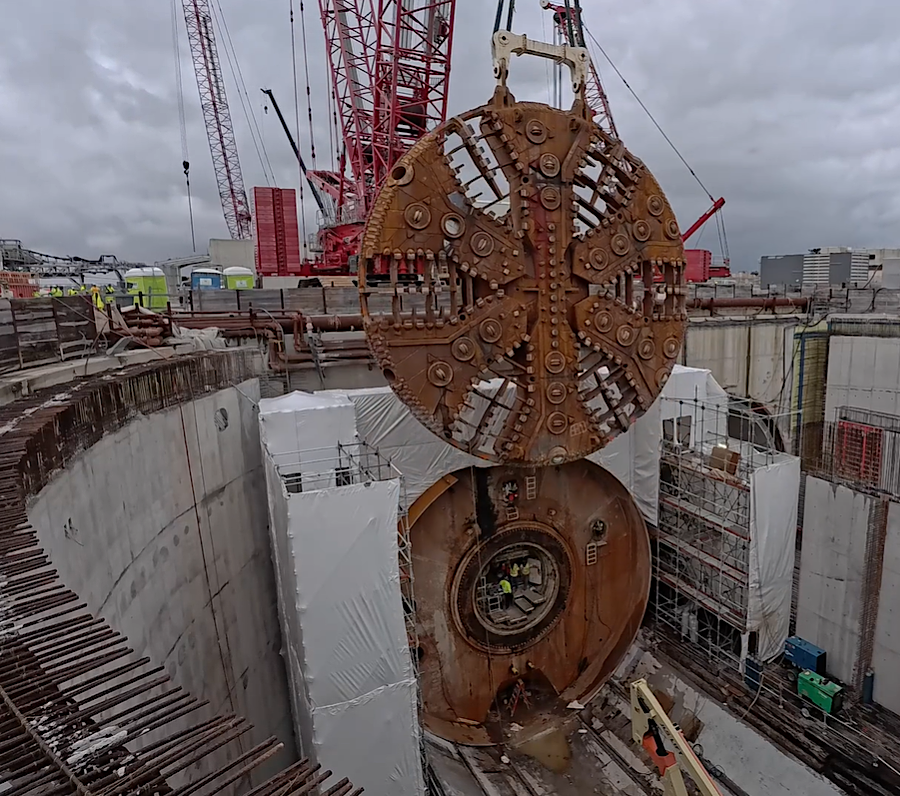

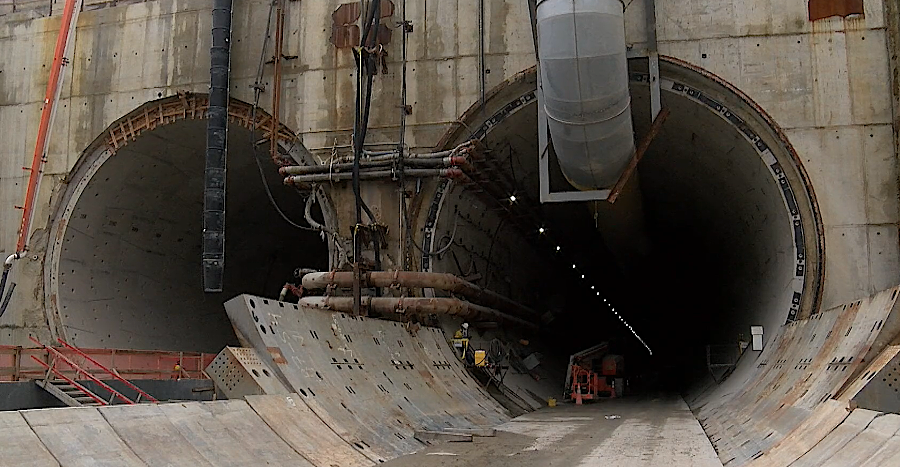

46' diameter boring machines excavated the parallel tunnels at the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Expansion Project, DBE/SWaM Opportunity Event (September 11, 2019)

the boring machines are as high as a four-story building and as long as a football field

Source: HRBT Expansion Magazine, Excavating Twin Tunnels Is Anything But Boring (May, 2020)

Boring a tunnel rather than using the traditional immersed tube method (digging a trench in the seabed, sinking tubes, and covering the trench again) minimized the environmental impacts of sediment disturbance. The start of the boring process required excavating a 75-foot deep pit on South Island. After six months to assemble the $100 million machine there, the tunnel boring machine spent a year digging a two-lane tunnel to North Island.

The 7,900 foot stretch of the westbound tunnel (for traffic deriving towards Hampton) between South Island and North Island required installing 1,191 concrete rings, with some as much as 173 feet below the surface of the water. After the machine reached the North Island, the 2,500 ton tunnel boring machine was lifted up to the surface in parts by 800-ton cranes. The parts were rotated 180 degrees starting with the cutterhead, then lowered 65 feet back into the excavated pit.

The first tunnel was completed in 51 weeks. Workers spent four months reassembling Mary before drilling eastward towards Norfolk on October 17, 2024. Based on experience, the machine was expected to complete the second two-lane tunnel within nine months. The second drilled tunnel, for traffic going eastbound, included 1,194 rings. The three additional rings were due to extra curvature.

When the tunnel boring machine completed the first bored tunnel in Virginia and reached the concrete-lined pit in North Island on April 17, 2024:4

the tunnel boring machine completed the first new tunnel in April, 2024

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Expansion Project, Project Tour & Information Videos and Monthly Project Newsletter (June 2024)

The sediments from the Yorktown Formation, excavated from within the tunnel, were carried by a slurry piping system back to the South Island. A Separation and Treatment Plant there isolated water from solid material. The water in the slurry was directed through a treatment plant before being discharged back into the Chesapeake Bay. After the tunnel boring machine made its U-turn at North Island and began to bore a new hole for the second tunnel, the pumping system was extended. The slurry continued to flow to South Island for treatment.

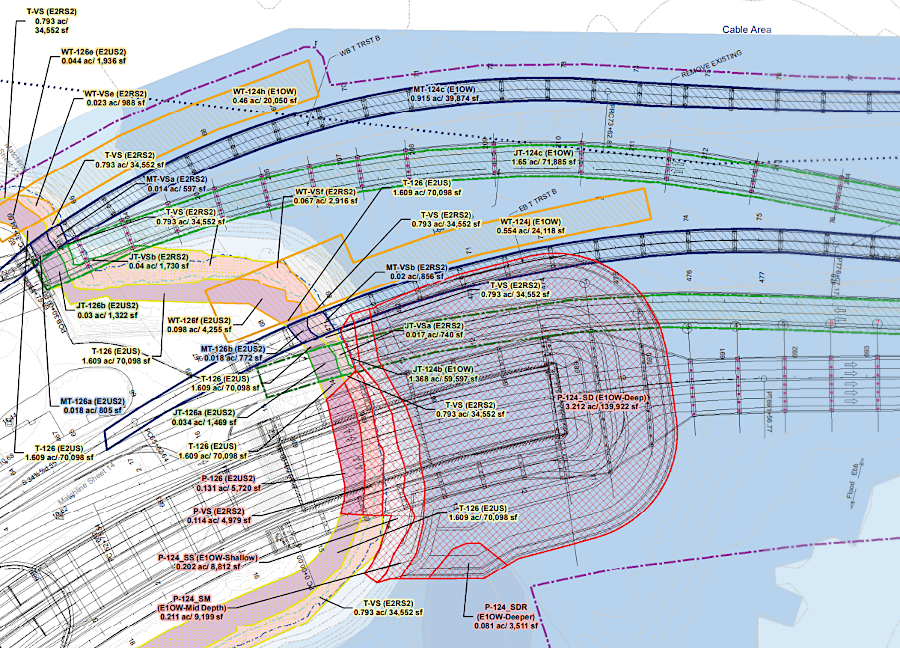

North Island, where the tunnel boring machine made a U-turn, had to be expanded to add two tunnels

Source: I-64 Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Expansion Project, Joint Permit Application and Drawings, Appendix L - Materials Management Plan, Rev 2 (Attachment L-2)

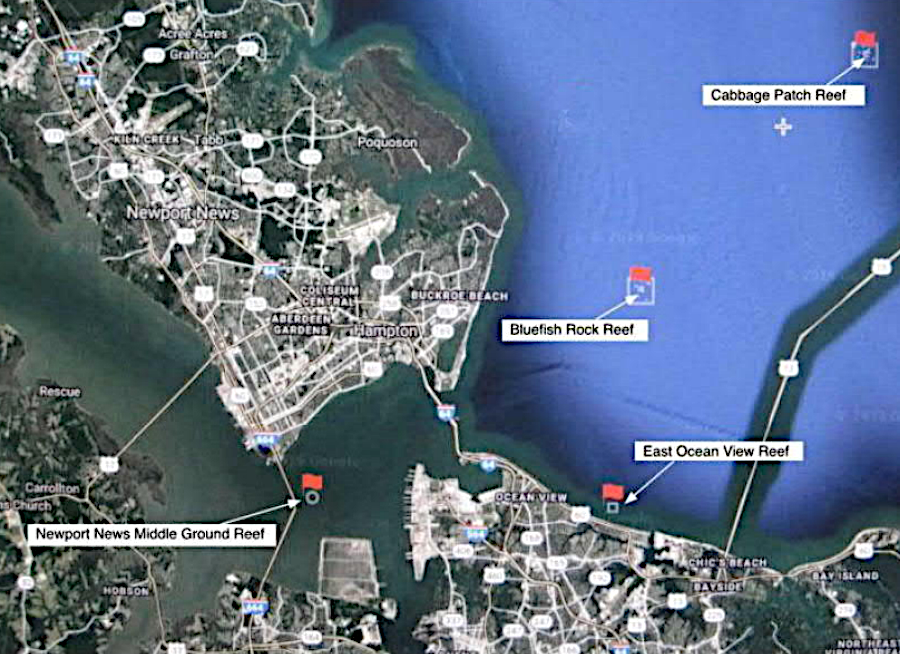

The concrete/steel from the trestles being replaced were recycled into artificial underwater reefs at Newport News Middle Ground Reef, East Ocean View Reef, Bluefish Rock Reef, and Cabbage Patch Reef. Such disposal required permits from the Virginia Marine Resources Commission.

material from the trestles being replaced were recycled into artificial reefs

Source: I-64 Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Expansion Project, Joint Permit Application and Drawings, Appendix L - Materials Management Plan, Rev 2 (Figure L-11)

The contractor anticipated that some of the solids in the slurry and dredged material would be suitable for beach replenishment, though Virginia Beach declined to accept any. Because the tunnel boring machine did not use foaming agents where the blades cut through sediments, excavated material with little or no Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons (TPH) could be barged 65 miles to Port Tobacco at Weanack (Shirley Plantation) for disposal.

Other solids could be barged 17 miles to the PreCon Marine facility, then loaded into watertight trucks for transport to the Dominion Recycling Center (former Higgerson-Buchanan) in Chesapeake. Planners anticipated that site could construct a lined landfill if required.

solid material excavated by the tunnel boring machine could be barged to the PreCon Marine facility on the Elizabeth River, then trucked to the Dominion Recycling Center

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Excavation was projected to be faster than disposal. The tunnel boring machine was planned to dig only five days a week, but waste disposal would continue for the other two days.

The tunnel boring machine was named Mary in honor of Mary Winston Jackson. She was a "computer" for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, and then its successor the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Her accomplishments in overcoming racial discrimination, segregated in the West Area Computing Unit, and becoming the first black woman to be employed by NASA as an engineer were a key part of the 2016 movie "Hadden Figures." NASA had named its headquarters building in Washington, DC after her in 2020.5

the tunnel boring machine name honored a National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) engineer, Mary Winston Jackson

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), NASA Names Headquarters After "Hidden Figure" Mary W. Jackson

Though both the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel and the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel chose to use tunnel boring machines to dig out sediments for construction of new tubes, there was a significant difference between the two projects.

The Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel experienced a delay at the start of its work. Contractors needed to move the rip-rap and expand the island at the southern end of the Trimble Shoal channel to install their tunnel boring machine, which required soft soil for its excavation work. Plans were to drive steel pilings through the large (2-4 ton) granite boulders, to create a coffer dam that would maintain adequate protection against erosion before the rip-rap boulders could be replaced. However, the rock layer was deeper and thicker than anticipated; pushing the steel pilings through the boulders was not easy.

Mary arrived at the end of 2021. The 4.5 ton machine was shipped in about 170 pieces, so six months of assembly was required before digging could begin in 2022.

a model of the tunnel boring machine, which arrived in Hampton Roads in about 170 pieces that required six months to assemble

Source: WVEC, Tunnel boring machine "Mary" officially unveiled for HRBT Expansion Project

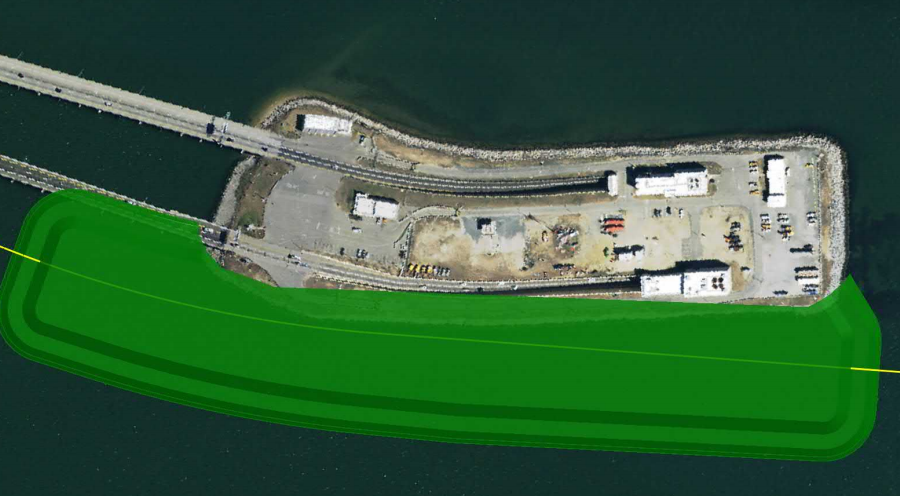

At the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, the South Island was already wide enough to provide a starting point for excavation by the tunnel boring machine. The North Island had to be widened so the machine could be turned around and dig a second tunnel back to the South Island.6

South Island was expanded on the southern end, with two new tunnels plus trestles replaced

Source: I-64 Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Expansion Project, Original Joint Permit Application and Drawings - Joint Permit Application Impact Plates (Sheet 15 of 38)

the tunnel boring machine started digging from the South Island of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel towards the North Island

Source: HRBT Expansion Project, Virtual Open House Recordings - Portals and Tunnel Construction Activity (January 28, 2021)

the interior of the first bored tunnel, before the roadway was constructed

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), HRBT Expansion Project (October 9, 2024)

Between April 2023-September 2025, a Tunnel Boring Machine named "Mary" excavated two tunnels between South Island and North Island. When completed, eastbound traffic going from Hampton to Norfolk will use those two new tunnels. Mary started digging at the South Island and reached the North Island on April 17, 2024. It took six months to remove the machine from underground, turn it around, and start the return trip to the South Island.

the North Island was widened in order to turn the tunnel boring machine around and excavate a second tunnel back to South Island

Source: HRBT Expansion Project, June/July 2021 HRBT Newsletter, Project Progress Photos (July 2021), and December 2021 HRBT Newsletter

On September 24, 2025 the 46-foot diameter, 500-ton cutterhead broke through and completed excavation of the second tunnel. The machine was then disassembled, piece by piece, and returned to Germany for its manufacturer to reuse components.7

on September 24, 2025, Mary broke through on the South Island after building the second tunnel

Source: WHRO Public Media, HRBT expansion hits milestone as final tunnel breakthrough completed; Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Mary's Breakthrough & Beyond (September 24, 2025)

the Tunnel Boring Machine (Mary) was disassembled after it returned to the South Island

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Mary the TBM Cutterhead Lifted out of the HRBT South Island Receiving Pit

In late 2019, the Virginia Department of Transportation paved over the south island of the tunnel in preparation for using it as a staging area support 200+ workers daily. Over 25,000 seabirds had taken advantage of the predator-free island after the original Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel had been constructed 40 years earlier. The site provided 98% of the nesting habitat for Virginia's royal terns, but paving the island meant that when they migrated back north in Spring 2020 their habitat was gone.

Options to mitigate the environmental impact of the expansion of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel had included providing an alternative nesting site on Willoughby Spit, but the US Navy had objected. It feared there would be an unacceptable risk of birds striking aircraft flying from nearby military bases in Norfolk.

Other options considered by Virginia Department of Transportation were to expand the island to provide four acres just for the birds, or to put 24 barges next to the island as replacement space for breeding and roosting.

the South Island of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel was transformed in 2021

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Expansion Project, HRBT Expansion Magazine (Summer 2021)

The search for an alternative ended, after the Trump Administration changed environmental policy and no longer required mitigation for "incidental bird takes."

The Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (now Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources) requested assistance from the US Army Corps of Engineers to build a new 10-acre island, using sediments dredged from the shipping channels in the area. While that island would provide essential habitat for the seabirds, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) biologists warned that adding an island would negatively impact various fish species.8

the south island of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel was home to 25,000 nesting seabirds until it was paved in 2019, but replacement habitat was upgraded on Rip Rap Island for the 2020 nesting season

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

After a public uproar about the destruction of the nesting habitat, the state decided to use Rips Rap Island, site of historic Fort Wool, for the 2020 nesting season. If extra space was required, up to 33 barges could be added. Trained border collies and their handlers were hired to patrol the south island, already paved over, to drive birds attempting to nest over to the sandy areas created around Fort Wool.

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Flyaway Geese Bett working on South Island

Though Federal officials were no longer objecting to disruption of the bird habitat, the General Assembly had to revise state law in April 2020. The change allowed Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries to move nests with eggs in them which had been laid by the gull-billed tern, a species listed as "threatened" within Virginia.

The long-term plan was to build a separate island just for the birds, one where it would be harder for the rats at Fort Wool to destroy the nests and would be in a location where disruption of the river's bottom would be acceptable to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.9

Wildlife managers were comforted when the first returning birds chose to use the nesting area prepared at Fort Wool:10

By 2025, it was routine work to keep the birds nesting only on the barges and Fort Wool. Buildings on South and North Island were covered with wire. Dogs managed by handlers from a private company, Flyaway Geese, patrolled the islands to force birds of 80-100 species to fly away. If a bird managed to build a nest and lay an egg, the site would have to be roped off and protected until the chicks fledged.11

the tunnels constructed in 1957 and 1976 each carried two lanes of traffic

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), RTS_0917a (by Tom Saunders)

a new trestle to the North Island was under construction in 2022

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel,

Project Progress Photos (January 2022)

widening of the bridges showed obvious progress by the end of 2023, while the tunnel boring machine was digging northward underneath the water

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), HRBT Expansion Project Newsletter (November 2024)

expansion includes adding two tunnels, replacing existing trestles, and widening/replacing bridges

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Expansion Project - Norfolk City Council Update (February 4, 2020)

the cutterhead of the tunnel boring machine

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, February 2023 HRBT Newsletter

almost 2,000 separate concrete rings were installed for each tunnel by the Tunnel Boring Machine (TBM) named "Mary"

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, May 2025 HRBT Newsletter

headwall of the two new tunnels, on North Island looking south in 2025

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Expansion Project, HRBT End to End project 6-26-25/a>

the trestle to the South Island, under construction in early 2022

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel,

Project Progress Photos (January 2022)

new eight-lane South Trestle bridge under construction

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, Monthly Project Newsletter (October 2023)