the Blue Ridge Tunnel crosses underneath I-64, US 250, and the Blue Ridge Parkway at Rockfish Gap

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the Blue Ridge Tunnel crosses underneath I-64, US 250, and the Blue Ridge Parkway at Rockfish Gap

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Louisa Railroad wanted to build an extension west of Charlottesville into the Shenandoah Valley, but the company could not afford the cost and risk of building across the Blue Ridge. To solve that problem, the General Assembly had the state build the extension, including the four railroad tunnels.

In 1849 the legislature chartered a new company, the Blue Ridge Railroad. It had the responsibility of constructing 17 miles of track from where the Louisa Railroad ended, 11 west of Charlottesville, to Waynesboro on the South Fork of the Shenandoah River. The General Assembly also rechartered the Louisa Railroad as the Virginia Central in 1850, retaining the arrangement where it would have exclusive right to use the Blue Ridge Railroad.1

The first railroad tunnels constructed in Virginia were built in the 1850's on Afton Mountain, between Waynesboro and Charlottesville. Three small tunnels on the east side of the mountain, and the 4,273-foot long Blue Ridge Tunnel at Rockfish Gap, enabled trains to cross the Blue Ridge. At the tunnel's deepest point, trains were 720 feet below the surface of Scott Mountain.

The tunnel was cut through lava which erupted 550 to 575 million years ago, plus sand and mud/silt sediments that were later deposited on top. The lava and sedimentary layers were then metamorphosed during orogenies as tectonic plates collided. The collision of African with North America caused the Alleghenian Orogeny 320-250 million years ago. That cracked the edge of the North American continent and thrust a cracked slice, known today as the Blue Ridge, westward from what is modern I-95.

When workers cut the Blue Ridge tunnel through the bedrock, most of their effort was excavating through the metamorphosed lava, a hard rock called greenstone in what is now labelled by geologists as the Catoctin Formation. Sandstone sediments trapped between lava slows were metamorphosed during the Alleghenian Orogeny into sausage-shaped blobs, reflecting their greater resistance to distortion than the lava.

The blobs within the Catoctin greenstone are described as "boudins," which is the French word for sausage. William and Mary geologists refer to one section of the now-exposed bedrock as the "Hall of Boudins."2

in 1848, no railroad crossed the Blue Ridge yet

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the internal improvements of Virginia (Claudius Crozet, 1848)

During construction, trains traveled on temporary tracks with steep grades and tight curves around Brooksville tunnel, Robinson's Cut, and Rockfish Gap. Workers needed supplies and equipment to excavate tunnels and cuts (trenches through the bedrock) from both their east and west portals.

Claudius Crozet engineered the tunnels at Afton Mountain. He had served twice as the principal engineer for the Virginia Board of Public Works, and was hired in 1849 as the chief engineer for the Blue Ridge Railroad Company. The Blue Ridge Tunnel, the longest in the United States until the Hoosac Tunnel was completed in Massachusetts in 1875, is also known as the Crozet Tunnel. It remains the longest tunnel in the Unitred States dug by hand, with black powder used for blasting the rock, and with no ventilation shafts.

Crozet broke the project into 16 sections, awarding separate contracts for each one. After his initial survey of the route he originally planned to build just two tunnels, then added one more in 1849 and finally the Little Rock Tunnel in 1853. The long tunnel at the crest of the Blue Ridge was the most challenging of them all.

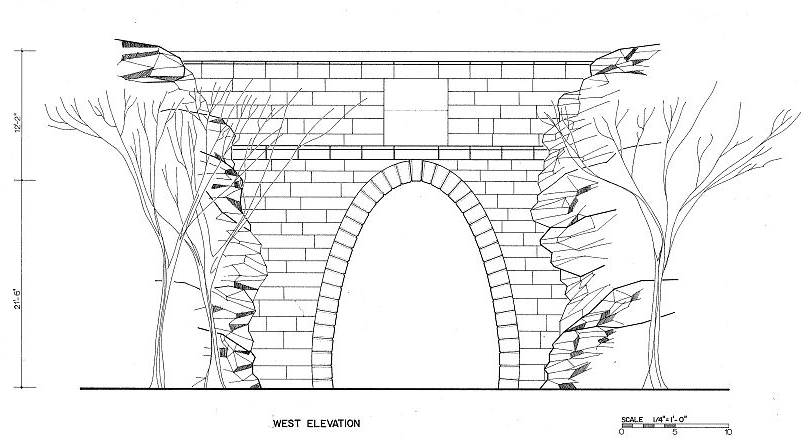

Crozet awarded a separate contract for constructing a railroad bridge over the Rockfish Gap Turnpike. The bridge required skilled labor to shape stones and build arches. The contractors in that area had bid prices based on simple excavation of railroad cuts and moving dirt to build a flat base for the track, and were unwilling to include the bridge.

since 2001, Nelson County has been actively working to convert the original Blue Ridge Tunnel into a tourist attraction

Source: WVPT, The Blue Ridge Tunnel

In addition, though the project was surrounded by Blue Ridge bedrock, finding the appropriate stone was a challenge. Crozet reported:3

Two contractors were hired to build the tunnels. John Rutter was supposed to complete the large Blue Ridge Tunnel, while John Kelly was responsible for the others. Rutter soon demonstrated he could not get the work accomplished and Kelly built all the tunnels. (John Larguey was his partner for the Blue Ridge Tunnel.)

The contractors building the sections of track, the railroad bridge over the Rockfish Gap Turnpike, and the tunnels hired white Irish immigrants for pay. Father Daniel Downey, the Catholic priest based in Staunton, provided religious services for the Irish workers. He used a plank chapel on top of Afton Mountain until it burned in 1857, when the tunnel was nearly complete.

Father Downey lost his position as a priest after apparently killing an Irish stonemason who had gotten his Irish maid pregnant. Despite four court trials, the priest was never convicted. He left his position in the Roman Catholic church and taught school, then operated a shop, in Staunton.

Crozet's contractors hired mostly Irish workers who moved to the job site looking for work. There were few local farm laborers in the area, and they were no available to work throughout the year. The Irish erected one-room houses, 10x14 feet large, and lived in those shanties during the construction project. After 1853, once three shifts per day were working, there were about 100 Irish workers living near each portal of the Blue Ridge Tunnel.

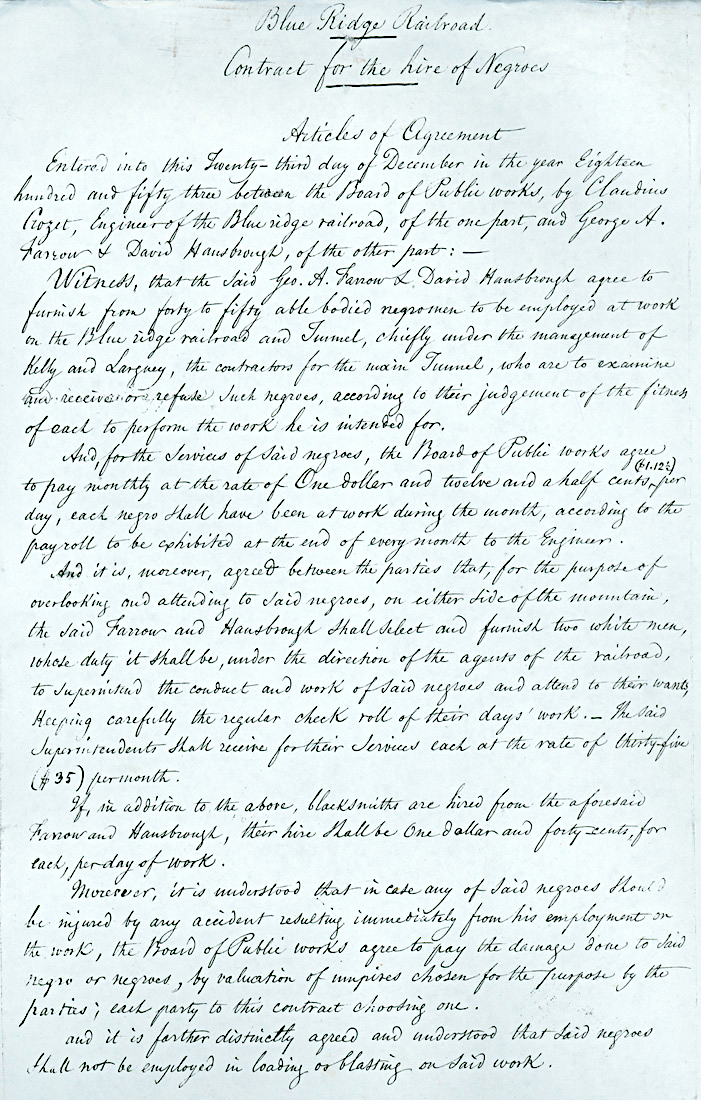

Slaveowners in the area were reluctant to rent their enslaved men for an entire year. Crozet ended up with 800 Irish building track and tunnels in Albemarle County vs. 200 enslaved men, which Crozet estimated in 1852 would cost 25% less than the Irish. The Irish would not work on the 36 Holy Days in the calendar, and they went on strike in 1853 and earned higher wages, because Crozet could not hire enough enslaved people to replace them. Most of the enslaved workers were used in 1854, under one year contracts signed by their owners as Crozet sought more labor after the 1853 strike.

A cholera epidemic in 1854 killed an unknown number of Irish workers and their families. None of the enslaved workers caught the disease, perhaps because they were housed separately and also because their owners withdrew them away from the tunnel.

At least 14 of the Irish died in construction accidents. In the 1850's, there was no workers compensation program and no death benefits for the Irish workers injured or killed on the job.

Social tensions between the Irish and the enslaved workers were reduced by directing them to tasks that kept them separate. Crozet wrote to the Board of Public Works:4

The Blue Ridge Railroad used enslaved workers in 1854

Source: University of Nebraska, Railroads and the Making of Modern America, Contract for Negro Slaves, December 23, 1853

What is documented is an 1850 fight between Irish workers known as the Fisherville Rebellion. Workers who had emigrated from County Cork in southern Ireland left their housing on the east side of the Blue Ridge, and marched across the mountain to attack the workers from County Connaught living near Fisherville. Those men had come originally from northwestern Ireland to build the western end of the Blue Ridge Tunnel and the railroad track down the western face of the mountain.

A house at Fishersville was burned before militia from Staunton arrived to separate the rival groups. The local newspaper reported:5

Crozet resented the ability of the Irish to press for higher wages. He proposed to the Board of Directors on December 6, 1853:6

Crozet arranged for 33 enslaved men to work on the tunnel, signing a one-year contract to pay their owners. The Blue Ridge Railroad had to feed the enslaved men, but they were not paid wages for their work.

The enslaved workers were unable to go on strike, but their owners still ensured a measure of worker protection to protect the value of the "property" being rented for the construction project. The contract prevented Crozet from assigning any of the enslaved men to blasting. They worked instead as "floorers," removing the rock already blasted from the working face of the tunnel.

Despite that precaution, two of the enslaved men were killed. On April 6, 1854, rail cars loaded with dirt separated from the locomotive when an iron pin broke. The cars raced down the track and smashed into a handcar, killing two enslaved workers on it.

The Virginia Attorney General ruled that the Blue Ridge Railroad was responsible for compensating the slaveowner for the loss of his property. No mention was made of compensating the families of the dead men; in the culture of industrial slavery, the need for such payment would have been a foreign concept. Crozet then stopped using slave labor, to avoid the risks of compensation.7

the Blue Ridge Tunnel, engineered by Claudius Crozet, was the first tunnel to be completed in Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Southeast End of Tunnel - Blue Ridge Railroad, Blue Ridge Tunnel, U.S. Route 250 at Rockfish Gap

The tunnels were designed to be 16' wide and 20' high, for one railroad track. Crozet noted the dimensions would be sufficient if the gauge was widened later and would provide:8

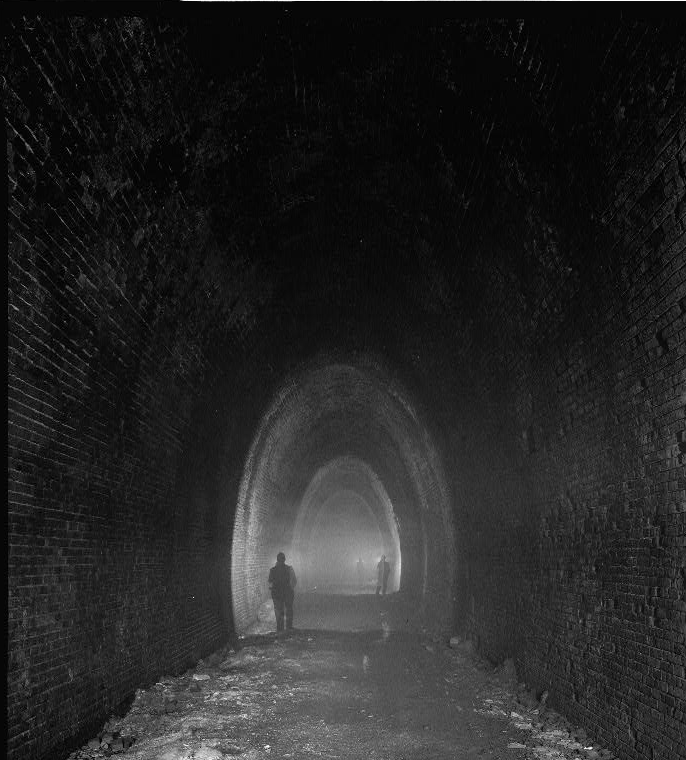

the western end of the tunnel was reinforced with a brick lining

Source: Library of Congress, Interior of Blue Ridge (Crozet) Tunnel

The construction process involved hard manual labor to drill a hole in the rock:9

Black powder was pushed into the hole; dynamite had not been developed when the Blue Ridge Railroad cut its four tunnels through the Blue Ridge. Lighting a fuse led to explosion of the powder, and it was dangerous work to approach a hole to relight a fuse which failed. After the black powder explosion cracked the rock, more hard labor was required to pry loose and break up the chunks of rock. Pieces were then lifted, by hand, onto a cart and hauled away.

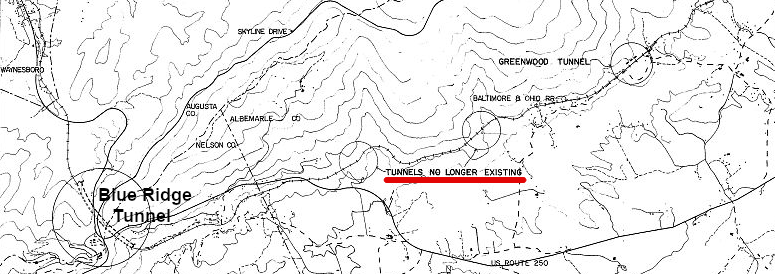

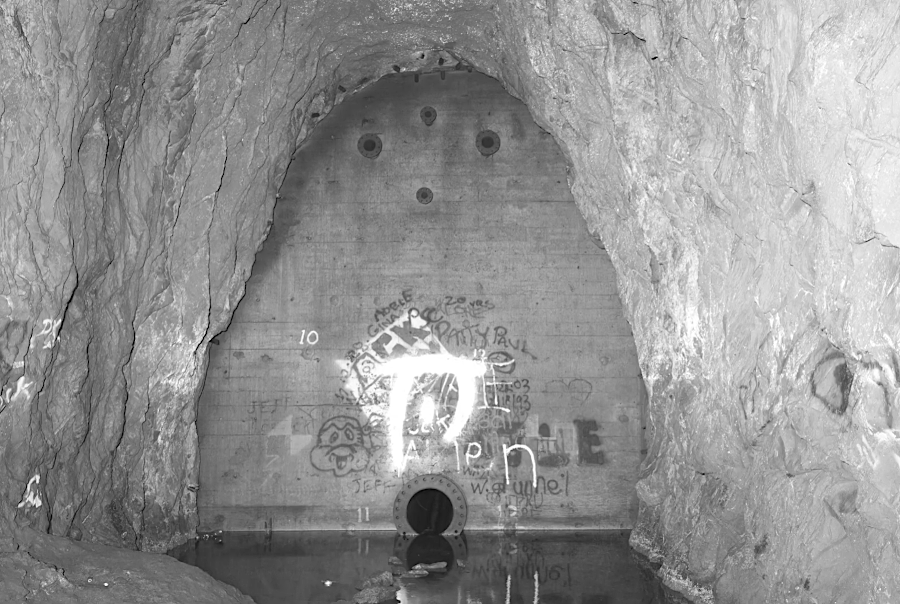

The 536-foot long tunnel closest to Charlottesville was named the Greenwood Tunnel, and was built in 1850-1854. The rock was hard enough to require blasting, but with so many fractures that it would slide into the tunnel if not supported. Construction was abandoned twice and the laborers discharged, until a contractor managed to complete it. Roof arches were extended beyond the east and west portals, to protect the tracks from future slides.

the east portal of the Blue Ridge Tunnel

Source: HathiTrust, Claudius Crozet; his story of the four tunnels in the Blue Ridge

West of the Greenwood Tunnel was the 869-foot long Brooksville Tunnel, completed between 1851-1856. Twice during construction a portion of the roof collapsed, and te entire tunnel was lined with brick to ensure stability. A major crack had to be repaired during the Civil War. Further west, between the Brooksville Tunnel and the Blue Ridge Tunnel, was the 100-foot long Little Rock tunnel completed in 1854.

The first 150 feet of the eastern portal of the Blue Ridge Tunnel passed through hard rock. As Crozet had anticipated, the roof on the eastern side required no support once the tunnel had been blasted. As excavation progressed, at one spot water had seeped into the bedrock and some rock crystals had changed into clay. Workers installed a frame of strong wooden timbers to provide initial support, until a brick tunnel roof in the shape of an arch could be completed there to support the decomposed rock overhead.

Near the western portal, the Blue Ridge Tunnel cut through metamorphosed Chilhowie Formation sediments rather than the Catoctin Formation. The metamorphosed sediments had been deposited as sandstones around 500 million years ago and metamorphosed into quartzite around 320-250 million years ago. They cracked and collapsed onto the workers more easily than the Catoctin Formation which the workers encountered at the eastern portal within most of the tunnel.

To deal with the less-stable bedrock at the western portal, Crozet had the workers create an arched roof made with two million bricks. Carving the tunnel through the softer rock there did not go faster than blasting though the hard Catoctin Formation, because extra effort was required in the confined space for bracing the roof and constructing the brick arches.10

the east portal of the Greenwood Tunnel

Source: HathiTrust, Claudius Crozet; his story of the four tunnels in the Blue Ridge

three tunnels, constructed initially as part of the Blue Ridge Tunnel project in the 1850's, have been converted into railroad cuts

Source: Library of Congress, Historic American Engineering Record, HAER VA,63-AFT.V,1- (sheet 1 of 2) - Blue Ridge Railroad, Blue Ridge Tunnel

The most challenging tunnel was the Blue Ridge Tunnel at the crest of the mountain. It sloped upward gently from the eastern entrance, at 1,430 feet in elevation, to the western entrance at 1,500 feet.

Construction began on February 14, 1850. Workers advanced towards each other from each end; for the first time, no vertical shaft was constructed in the middle. Progress averaged 26 feet per month on each end, using drills to make holes for black powder to blast rock free.

As workers carved into the mountain, the tunnel had to be ventilated. Crozet chose not to use a steam engine to power fans, fearing the equipment would break down to often and stop work. He used mules to power a pump outside each portal, with pipes made of gutta percha extending into the tunnel to extract dust and smoke from blasting at the working face. Separate pumps siphoned water through three-inch diameter iron pipes, removing over 40 gallons per minute.

Muscle power, not machinery, was key to drilling holes and shoveling the blasted rock into carts for removal. About 800 workers were involved in the construction project.

The workers coming from two sides met on December 25, 1856, when the tunnel was "holed through." After eight years of difficult construction, trains began using the tunnel on April 13, 1858.11

After workers on the west portal excavated the first 900' of material, they exposed a fracture filled with water. Mule-powered pumps kept the water levels down as various veins were encountered, but the workers deep underground struggled to stay dry. Though Merle Travis's lyrics describe mine tunnels as a place "where the rain never falls and the sun never shines," the Blue Ridge Tunnel was wet. Water still drips into it today from fractures in the bedrock, and ditches are required to keep the modern recreational trail dry.12

even today, the original Blue Ridge Tunnel is wet from seepage through rock fractures

Source: WVPT, The Blue Ridge Tunnel

Crozet managed to connect the two ends of the tunnel on December 29, 1856, before the 1857 financial "panic." That economic recession, among other things, ended plans to complete the Manassas Gap Railroad by building a separate line to Alexandria rather than use tracks of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad from the junction at Manassas.

the eastern end of the Blue Ridge Tunnel, cut through Catoctin greenstone, did not need brick reinforcement like the western end through the metamorphic Chilhowee sediments

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Blue Ridge Tunnel and Blue Ridge Tunnel (by Trevor Wrayton)

Crozet's success stands in contrast to the efforts of another Blue Ridge Railroad. South Carolina planned to build a line from Charleston to the Ohio River, but the state legislature lost patience as the costs to build Stumphouse Mountain Tunnel through the Blue Ridge kept climbing. The South Carolina tunnel project was stopped in 1859.

Had that tunnel been completed, it would have been 5,682 feet long and surpassed Crozet's tunnel as the longest in the world. When the Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio Railway made its rail connection from South Carolina across the Blue Ridge, it followed a different route rather than complete the Stumphouse Mountain Tunnel. Today the unfinished tunnel is a park where visitors can explore the failed project.13

Between 1854-1858, a temporary track was built across the top of the Blue Ridge by an engineer from the Virginia Central Railroad. The Mountain Top Track enabled trains to bring equipment, supplies, and people to the west portal where some of the Irish workers lived in shantytowns, and to carry revenue freight and passengers between Richmond-Staunton. Construction of the temporary railroad took seven months, and required building bridges across six mountain ravines to reach the summit at 1,885 feet.

The three steam locomotives used on the temporary track were modified to increase traction on the rails. Water tanks were added onto the boiler, and firewood was carried on the engine as well. The extra weight of water and wood enabled the locomotives to climb the steep grades and push through snow in the winter. Three loaded cars, or four empty ones, could be hauled by a locomootive goinf 7.5 miles per hour uphill and 5.5-6 miles per hour on the descent.

As described by Charles Ellet, the engineer responsible for the Mountain Top Track, the temporary track climbed 610 feet in elevation on the eastern side and 450 feet on the western side. Grades were steep:14

In Virginia, the Blue Ridge Tunnel was "scaled" in 1887 and again in 1912. Rock was scraped away within the interior in order to accommodate taller and wider rolling stock. A replacement tunnel at the crest of the Blue Ridge was built in 1942-44 to accommodate wider trains. Also during World War II, the smaller Brooksville tunnel was "daylighted" with the roof removed. The Greenwood Tunnel was bypassed by excavating a railroad cut, and that tunnel was sealed with concrete.

the Greenwood Tunnel was bypassed and sealed up by the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in 1944

Source: buxelbow, Claudius Crozet Train Tunnels

the Greenwood Tunnel is now sealed

Source: Library of Congress, Northeast portal of tunnel. Concrete buttresses were added at a later date

The 80-foot long Little Rock Tunnel cut through hard rock and required no brick lining, so that tunnel was enlarged as part of the project to replace the Blue Ridge Tunnel in 1944. The Little Rock Tunnel had been finished in 1854, when Crozet revised his original plans. He decided that digging a short tunnel would be quicker that excavating a cut, and faster work was needed to put into use the temporary track built by the Blue Ridge Railroad to bypass the incomplete Brooksville and Blue Ridge tunnels.

The Little Rock Tunnel was the first to be completed, and today is the only one of Crozet's original four tunnels still in use.

Confederate forces protected the tunnel throughout the Civil War. rains acilitated moving troops and supplies between Richmond and the Shenandoah Valley. During the Valley Campaign in 1862, General Stonewall Jackson fooled Union forces by marching his army east on a road across a gap in the Blue Ridge. He then doubled back, carrying troops on trains through the tunnel, and had superior forces for his success at the Battle of McDowell west of Staunton.

The Union was finally able to get into the tunnel at the very end of the Civil War. After the last Confederate army in the Shenandoah Valley was defeated at the Battle of Wayneboro on March 1865, Union cavalry wrecked the tracks of the Blue Ridge Railroad. The four tunnels were not damaged, and repairs were completed by July 1865. During World War I and World War II, there was a guard at the Blue Ridge Tunnel to protect it from sabotage.

In 1907, a circus train wrecked inside the short Little Rock Tunnel. Cages filled with animals on one of the cars jostled loose during the trip from Charlottesville to Staunton. While going through the tunnel, a cage with a tiger was crushed and the tiger was killed. Other cages fell on top of five stowaway boys hitching a ride, and one boy was killed. The train journey was delayed half a day, in part to drop off injured animals at Basic City (Waynesboro) for veterinary care.

Local newspapers recorded various deaths of people in the tunnel. Some were disoriented when smoke from the coal-fired steam engine entered the the railroad cars while passing through the tunnel. Some pssengers climbed out the cars while the train was moving, trying to escape a perceived fire, and were crushed to death. One person who hopped on a freight train successfully passed through the tunnel by crawling into the tender to avoid the smoke, but then climbed out and hit his head on a bridge.

The tunnel served as a shortcut for a local doctor who had patients on both sides of the Blue Rdge in Nelson and Augusta counties. In the 1930's, he would drive his car through the tunnel. Reportedly:15

The Buckingham Branch Railroad, which now operates on the old Blue Ridge Railroad route, still uses the Little Rock Tunnel and the 1944 Blue Ridge Tunnel to cross the Blue Ridge. I-64 crosses north of the Little Rock Tunnel and over both the 1856 and the 1944 Blue Ridge tunnels as it goes across Afton Mountain.

the original Blue Ridge Tunnel was replaced by a bigger tunnel in 1944

Source: Library of Congress, General View of Entrance to Blue Ridge Tunnel (Left) From Southeast. Original Blue Ridge R.R. (Crozet) Tunnel Is Visible At Right

Nelson County began to focus on converting the 1858 tunnel into a tourist attraction in 2001. Providing a hiking path through that tunnel would give visitors one more reason to come to Nelson County and spend money at the breweries, wineries, cideries, and distilleries on Route 151.

Local residents who had traditionally explored through the Blue Ridge Tunnel without authorization were given a final opportunity to walk through it in 2017, before the site was secured. One made a comment that indicated why county officials thought an abandoned railroad tunnel might attract tourists:16

on St. Patrick's Day in 2021, "The Tunnel" was released on You Tube to highlight the Irish workers at the Blue Ridge Tunnel

Source: American Focus Films, The Tunnel (2021)

The Blue Ridge Tunnel Foundation is the non-government organization working in partnership with Nelson, Augusta, and Albemarle counties plus the City of Waynesboro to create a regional attraction. The University of Virginia used a robot to map a portion of the tunnel with Light Direction and Ranging (LiDAR) technology.17

Source: Mapping the Crozet Tunnel

Geologists have examined the bedrock, which for most of the tunnel is primarily a form of basalt called the Catoctin Formation. It was lava that oozed into fractures in the surrounding granite and flowed onto the surface. The Catoctin Formation was emplaced about 570 million years ago, and over 200 million years later tectonic forces had pushed it about 10 miles underground.

Heat and pressure metamorphosed the basalt into greenstone, rich in the greenish mineral epidote, as Africa and North America collided to form the supercontinent Pangea. That collision pushed the bedrock northwest 40-75 miles, so what is now exposed at Rockfish Gap may have been located near Richmond until the Alleghenian Orogeny. Later geologic forces brought the basalt back to the surface.

the 1858 tunnel was carved through greenstone with a semi-elliptical profile, to reduce the cost of excavating an oval ceiling

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Proposed Route of the Blue Ridge Tunnel Greenway

The basalt and granite/granodiorite is much more resistant to erosion than the limestone in the Shenandoah Valley to the west or the metamorphic rocks in the Piedmont to the east, so the Blue Ridge became a mountainous barrier to railroads. At only one location in Virginia, at Rockfish Gap, was the Blue Ridge crossed via a tunnel. The other crossings relied upon low "water gaps" where the Roanoke River and James River had cut through the bedrock, and at the "wind gap" of Manassas Gap. The Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire Railroad stopped in Loudoun County before trying to cross the Blue Ridge and reach the coal fields of Hampshire County.

Though it is resistant to erosion, the bedrock at the tunnel is fractured. Raindrops seep through over 700 feet of rock and reach the tunnel bore within days or weeks of a storm. The Blue Ridge Tunnel is deep underground, and always wet.18

"Single jacking" and "double jacking" were used to drill and blast the rock. In the single jack process, one worker holds and rotates the drill bit while a second worker swings the hammer to drive the bit into the rock. In the double jack process, two workers alternate swwinging a hammer while one holds and rotates the bit. The hole was filled with black powder, and after the explosion the shattered rock was removed by "floorers" and "muckers" until the rock surface was exposed for another round of drilling. Blacksmiths constantly re-sparpened the bits, which were quickly dulled by the hard bedrock.

By 1853, there were three crews so excavation of the Blue Ridge Tunnel was underway 24 hours/day for the next five years. Crozet had anticipated completing the tunnel in three rather than the eight years finally required. Progress was, on averge, 26 feet per month on each portal.

On the western end, the tunnel was carved through metamorphosed sedimentary formations before reaching the Catoctin Formation. The sediments are less consolidated, so workers encased the western 764 feet of the tunnel with a brick lining. The bricks were made from local clay, and had to be baked hard enough to meet Crozet's specifications.

The first trains passed through the tunnel in 1858 while the brickwork was still being completed on the western end. An additional 694 feet of brickwork was added later. Conversion of the abandoned Blue Ridge Tunnel into a public trail required repairs tob ensure that the bricks would be stable and not fall from the tunnel's sides and roof:19

the western portal was reinforced with a brick lining, since it was carved through metamorphosed sediments rather than greenstone

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, West portal of the Blue Ridge Tunnel

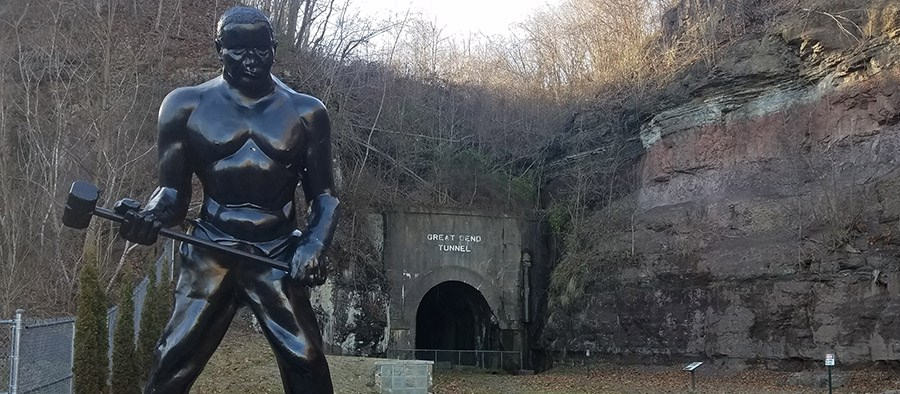

The Blue Ridge Tunnel was completed before steam-powered drills were available. After the Civil War, workers could use new technology, particularly dynamite, when carving out tunnels in West Virginia. Those tunnels were built by the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railroad, which was created in 1868 by merging the Virginia Central and the Covington & Ohio railroads.

In 1869, after values were depressed in the economic recession following the Civil War, Collis P. Huntington acquired control and arranged for financing of the long-planned extension to the Ohio River. The Chesapeake and Ohio's longest tunnel, the Great Bend Tunnel at the Greenbrier River, is a prime candidate for the location where the legendary "steel drivin' man" John Henry used his sledge hammer to race a steam drill. According to historian Scott Reynolds Nelson, Henry was a prisoner rented by the Virginia Penitentiary to the railroad.

The lungs of the workers building the tunnels were damaged by silica dust inhaled during construction. That dust facilitated tuberculosis and pneumonia, or directly caused death within several years through silicosis. The prisoners were unable to go on strike to obtain better working conditions, and:20

the "steel drivin' men" like John Henry who worked on the west end of the Blue Ridge tunnel were at the greatest risk of lung damage

Source: National Park Service, The Legend of John Henry: Talcott, WV

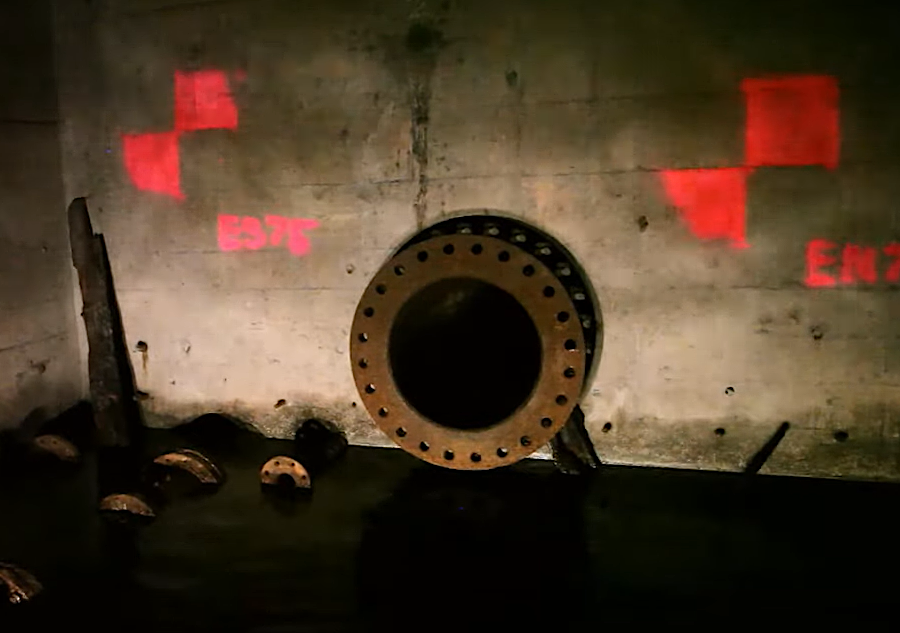

After the original tunnel was abandoned in 1944, it sat idle until the Bottled Gas Corporation tried to use it for storing propane. Two massive concrete bulkheads were constructed in the middle of the tunnel; one was 10 feet thick and the other was 14 feet thick. A 27" diameter pipe was incorporated within each bulkhead in order to pump gas in and out of the "thermos bottle" being created underground.

Only a 1,750 foot portion of the tunnel was prepared to store propane, to reduce the cost of sealing the walls to make them gas-tight. To have succeeded, the company would have been required to place a pressure-resistant concrete skin over all the tunnel surfaces between the bulkheads.

The project was never completed, in part because the fractures in the greenstone and gaps at the two bulkheads allowed pressurized natural gas to escape as fast as water seeped into the tunnel. The 1897 Giles County earthquake may have increased the fractures in the bedrock.

two concrete bulkheads built to store propane in the 1950's had to be removed to re-open the tunnel for pedestrian traffic

Source: YouTube, The Tunnel

People who explored the tunnel after the 1950's had to squeeze through the pipes in the bulkheads, located several feet above "ground level" (the bottom of the tunnel). Those explorers discovered that the thick concrete barriers prevented water from draining eastward (downhill) out of the tunnel, so a pool of cold water was commonly encountered between the bulkheads. After 1944, there was no maintenance of the drainage ditches originally constructed by the railroad; much of the tunnel was filled with water knee-high.21

the Blue Ridge tunnel was filled with water when Nelson County started to convert it into a tourist atttraction

Source: YouTube, The Tunnel Trailer

In the 1900's the Blue Ridge Tunnel became a chokepoint limiting the passage of newer, larger steam locomotives. During World War II, a second tunnel was excavated parallel to Crozet's tunnel - but using dynamite, and lining the inside with concrete to reduce rockfalls and the seepage of water. The new tunnel was finished in 1944. Coal-fired steam locomotives and now modern diesels still haul freight and passengers through it on a regular basis.

The 1944 tunnel was cut through the Blue Ridge with a roundhead arch, mimicking Crozet's design. It too is a single track tunnel. The dimensions of the 1858 tunnel bore are 16x21 feet, and the total length is 4,279 feet. The 1944 tunnel dimensions are slightly larger at 18x22 feet, and slightly longer at 4,230 feet underground.22

The Blue Ridge Tunnel constructed under the direction of Claudius Crozet by Irish and enslaved workers, and possibly some skilled free black men, was abandoned after 86 years of use. To convert the abandoned tunnel into a tourism attraction, Nelson County has invested more time than the eight years that were required for the tunnel's construction.

The county arranged with the CSX for the railroad to donate the tunnel in 2007, charging only $1 for the asset. Nelson County then obtained a $750,000 Transportation Alternatives Program grant in 2013 from the Commonwealth Transportation Board for the first phase of a three-phase project. The Transportation Alternatives Program grants finance initiatives that highlight the cultural, historical and environmental aspects of roads and other transportation infrastructure.

Phase I was finished in 2015, producing a parking lot, trail, and fencing along the trail to the eastern portal. The fencing on the trail to the portal was an essential safety feature, separating visitors from trains using the still-active railroad tracks.

trains using the 1944 tunnel pose a hazard for tourists exploring the 1858 tunnel

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Finished phase one of the Proposed Route of the Blue Ridge Tunnel Greenway

trains still emerge from the eastern end of the 1944 tunnel

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Proposed Route of the Blue Ridge Tunnel Greenway near Crozet

The tunnel itself remained off-limits to public use after Phase I. To cope with interested-enough-to-trespass visitors, a few scheduled tours were offered to the general public. At that point, the potential tourism benefits were clear to Augusta County and the City of Waynesboro, as well as Nelson County.

To raise private funds, manage outreach and tours, and build local support, Nelson County joined with Augusta County, the City of Waynesboro, Albemarle County, the Virginia Department of Transportation, the Commonwealth Transportation Board, and the National Park Service in 2012 to establish the Claudius Crozet Blue Ridge Tunnel Foundation. The National Park Service managed the Blue Ridge Parkway south of the tunnel and Shenandoah National Park north of it, plus the Appalachian Trail passing over the Blue Ridge Tunnel.

The Commonwealth Transportation Board approved a grant in 2016 for the next two phases, with half of the grant going to Augusta County and half to Nelson County.

modern explosives were used to blast away the thick natural gas bulkheads so tourists could walk through the whole tunnel

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Gas Bulkhead at the East Portal ready for 2nd blasting

Phase II included blasting away the bulkheads constructed for the natural gas storage, installation of rock bolts, and making a trail within the tunnel.

bulkheads for a failed gas storage project had to be blasted out of the historic tunnel

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Blue Ridge Tunnel | Overview

multiple blasts were required to remove the rebar-reinforced bulkheads

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Blue Ridge Tunnel | Overview

Also part of Phase II was sealing some of the brick lining at the western end to reduce the risk of falling material, and coating the rock where the bulkheads were removed. Geologists encouraged the tunnel planners to minimize the amount of shotcrete used to stabilize the rock. A coating would block the potential to interpret how the Blue Ridge formed, and the drilling-by-hand challenges faced by the laborers in the 1850's.

brick lining inside the West Portal

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, West portal of the Blue Ridge Tunnel

some bricks at the West Portal have fallen from the lining

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, West portal of the Blue Ridge Tunnel

Bids came in higher than expected, and Phase II was delayed in 2018. Phase II ended up costing $3.7 million.

The Phase III component was designed to create parking at a trailhead on US 250 in Augusta County and a connector trail up to the western portal. Phase III, a $1.3 million project for the parking/trail in Augusta County up the mountain to U.S. 250, began in August, 2019. Including the $750,000 cost for Phase I, the three phases of the trail underneath the Blue Ridge ended up costing $5.75 million.

Source: WVPT Public Media

The 2.25 mile long (round trip) trail through the tunnel opened for public use in November, 2020. Parking lots were constructed on both ends so visits could start in either Nelson County or Augusta County. No lighting was installed, and those biking through the tunnel were cautioned to go slowly. Hikers with poor headlamps/flashlights might not be visible until the bikers were very close.

Nearly 7,000 visitors visited the tunnel during the first 10 days after it opened to the public on November 21, 2020.23

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Blue Ridge Tunnel | Overview

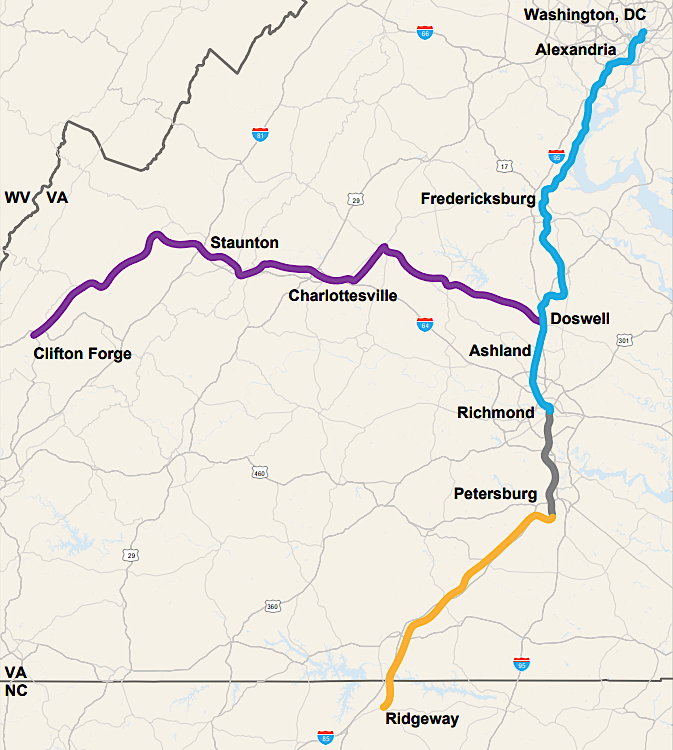

After Norfolk Southern donated the historic tunnel to Nelson County, the Commonwealth of Virginia negotiated a deal with CSX in 2019 to repurchase the modern railroad tunnel and former Virginia Central/Blue Ridge Railroad track. The purchase was was part of a 10-year, $3.7 billion Transforming Rail in Virginia project to acquire right-of-way and track that would allow for expansion of passenger rail service.

The state acquired all of the original Virginia Central track between Doswell and Clifton Forge, with the intent of offering Amtrak service on an east-west route someday. Buckingham Branch freight service continued as well. CSX sent empty coal cars from Newport News back into West Virginia via the Blue Ridge Tunnel route.24

CSX agreed in 2019 to sell the Virginia Central route (purple) to the Commonwealth of Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, Map of Future Program Highlights

Source: Charlottesville Inside-Out, Claudius Crozet Blue Ridge Tunnel Foundation, ParadeRest Virginia

Nelson County recognized the Blue Ridge Tunnel could be repurposed into a unique tourist attraction

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Partnership and Innovation - Engineering Directorate Leadership Meeting (2013)

brick reinforced the western entrance of the Blue Ridge Tunnel in Augusta County

Source: Library of Congress, Historic American Engineering Record, HAER VA,63-AFT.V,1- (sheet 2 of 2) - Blue Ridge Railroad, Blue Ridge Tunnel

west portal of the Blue Ridge Tunnel

Source: HathiTrust, Claudius Crozet; his story of the four tunnels in the Blue Ridge