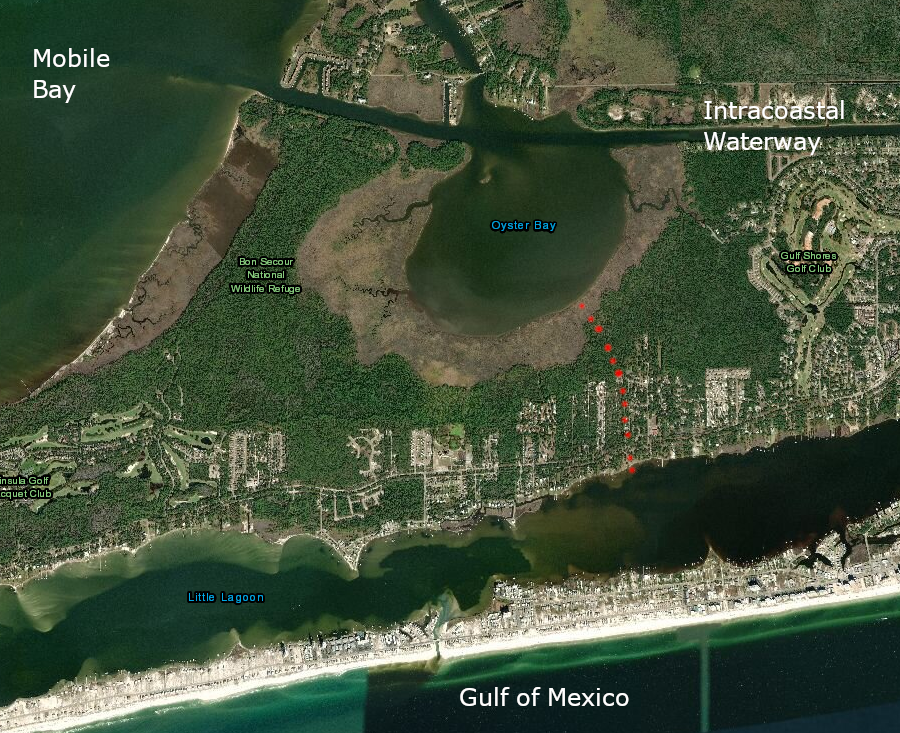

near the modern Intracoastal Waterway entering Mobile Bay in Alabama is evidence of a canal (red dots) excavated 1,400 years ago

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

near the modern Intracoastal Waterway entering Mobile Bay in Alabama is evidence of a canal (red dots) excavated 1,400 years ago

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The oldest transportation canals in North America were constructed by Native Americans in Florida and Alabama, 1,400 years ago. In Virginia, there is no evidence of any canal prior to the arrival of European colonists. One three-foot-deep canal built between 576 and 650 CE (Common Era) connected the Gulf of Mexico with more protected bays, and was a shortcut to avoid travel around a 19-mile peninsula. The canal may have required dams at either end to keep enough water in the canal for canoes to float.

In southwestern Florida at Pine Island, a 2.5-mile canal was built by the Calusa around 1,000 years ago. These canals were completed before the development of stratified, hierarchical societies in the Mississippian period, where chiefs could force lower-class people to serve as laborers. One archeologist noted about the early canal building:1

Canals were built in Virginia for two main reasons: waterpower and transportation. In western states irrigation canals are common, but not in Virginia.

The smallest of the canals, designed to provide mechanical energy from falling water, were simple ditches and flumes connecting millponds/creeks to gristmills. east of Tidewater, topography-conscious colonists found places to build mills. West of Tidewater, there was enough topographic relief for falling water to power gristmills on nearly every perennial stream.

Milldams in the creeks replaced the beaver dams, diverting water into millraces. Waterwheels at hundreds of grist mills were powered by a small, artificially-channeled flow of falling water that then rejoined the natural stream channel downstream of the mill. The millponds captured sediment from farm operations upstream, and blocked passage of both fish and boats, so the initial stream alterations interfered with transportation.

Haynes Pond still remains where the Burwell family established a mill on Carter Creek, on the flat Coastal Plain in Gloucester County

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Clay Bank 7.5x7.5 topographic quad

In the mid-1800's, large investments in canals far larger than millraces were made on many rivers in Virginia. In some cases, the canal building was for waterpower, but most of the money was focused on creating canals for transportation.

reconstructed grist mill, using waterpower for

grinding wheat and corn, at McCormick Farm (Steeles Tavern)

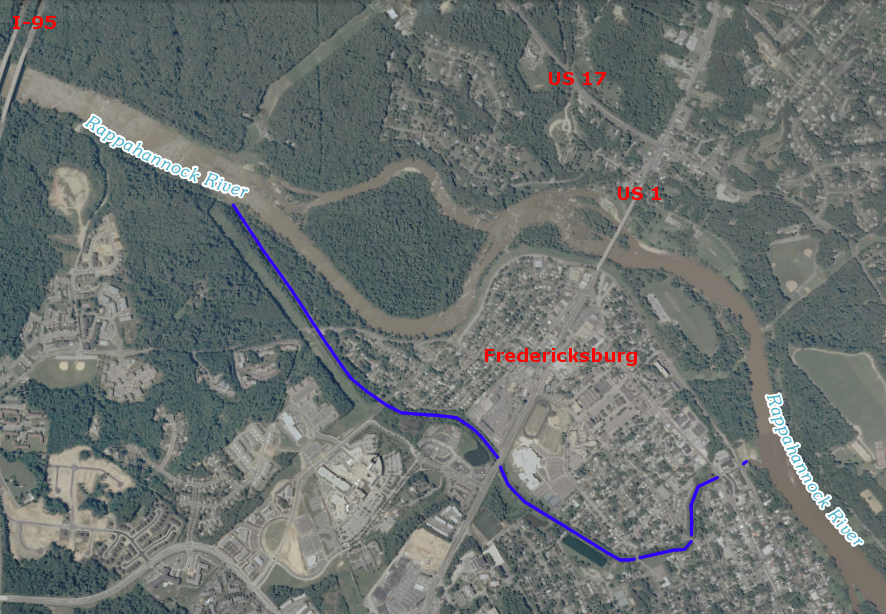

The main geographic rivalry was between advocates of improving transportation up the Potomac River through the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal vs. supporters of improving transportation up the James River via the James River and Kanawha Canal. The goal was to steer western trade through the ports of Alexandria and Richmond.

While business from Piedmont and Shenandoah farmers was desirable, the big prize was the business from the Ohio River Valley. As Americans moved west across the Allegheny Mountains, they ended up in the Mississippi River watershed. Roads were poor, and wagons pulled by horses and mules could carry only a limited amount of material, but boats could float grain, lumber, whiskey, hides, and other western products downriver to New Orleans. Eastern seaports wanted to divert that traffic across the mountains to the Atlantic Coast.

George Washington was a strong advocate of building canals as a way to unite the economic interests of settlers west of the Appalachian Mountains to the states on the Eastern Seaboard. He feared the western settlers shipping agricultural products down the Mississippi River would align with the Spanish government which controlled New Orleans, or establish trading links along the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River and become allies of the British in Canada.

There was a clear risk that the western settlers would not stay united with the original 13 states. Canals would create economic connections to Atlantic Ocean seaports, so Washington had a political agenda when he supported new transportation infrastructure that would cross the mountains. He also had an economic interest. Many of the 60,000 acres that he ended up owning were west of the mountains, and the value of those lands would increase if the cost of getting goods to market were lowered.

He wrote in 1785:2

The Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal would have offered a water route from Pittsburgh to Alexandria. The James River and Kanawha Canal would have intercepted the Ohio River further downstream, at Point Pleasant, and sent traffic to Richmond. Both transportation initiatives were planned initially as a series of skirting canals that would bypass the main falls/rapids (such as Great Falls) while requiring boats to rely upon water in the main river channel for most of the distance - and both grew in ambition to be totally separate channels, parallel to the rivers, with expensive locks to manage the changes in elevation.

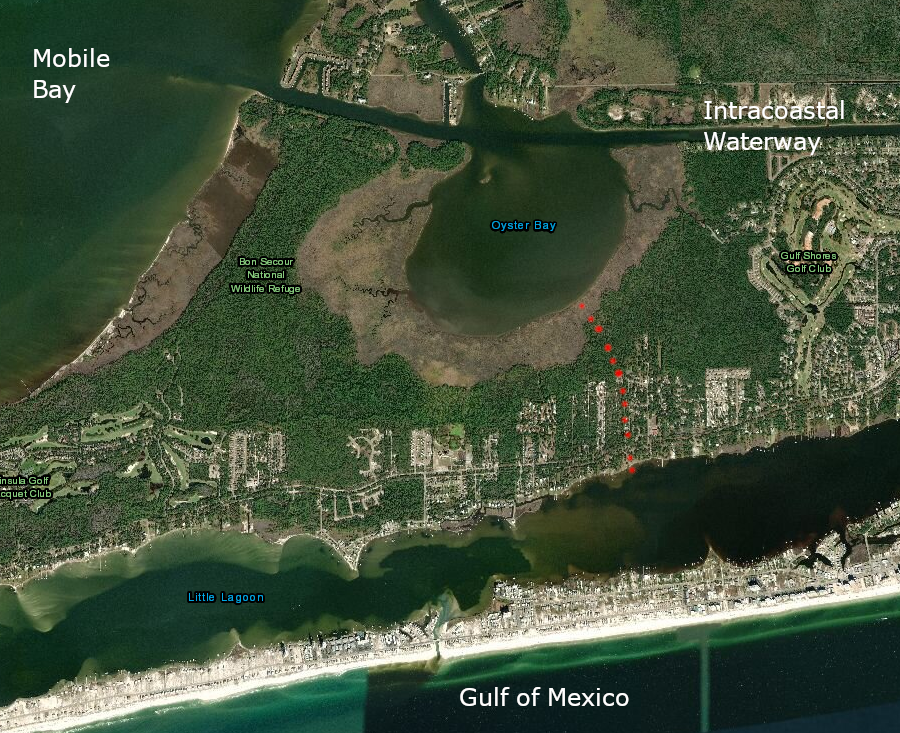

planned route of C&O Canal, showing unbuilt section (in red) between Cumberland and Pittsburgh

Source: Library of Congress, A map, of the principal canal and rail road improvments [sic],

which will connect with the Balt. & Susqa. Rail Road at York; drawn by G. F. de la Roche. C. Engr.

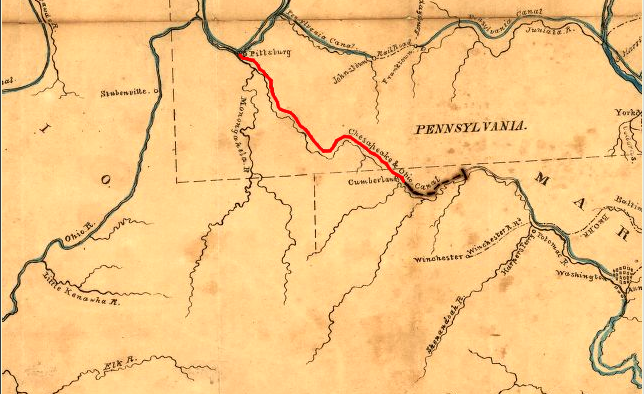

Richmond and Alexandria were not the only cities in Virginia with dreams of using canals to increase the economic "hinterland," the backcountry farming region that traded through a Chesapeake Bay port. In Fredericksburg, the Rappahannock Navigation Company tried to build a canal network 50 miles upstream of the Fall Line to the Blue Ridge, so farmers in the Rappahannock River watershed would do business with Fredericksburg merchants.

Construction started in 1829 and proceeded slowly. The Rappahannock Navigation Company lacked the resources to build a separate channel next to the river. Instead, it sought to build a series of locks and dams so batteaux (river boats) could float down the Rappahannock River, but bypass the shallow sections via locks adjacent to the river. After a rebuilding initiative in 1847-49, the infrastructure consisted of 80 locks (26 built of stone), 20 dams, and 15 miles of canal. As described in the nomination to the National Register of Historic Places:3

stones for a Rappahannock Navigation Company lock still remain along the river

Source: Fredericksburg Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (FAMPO), River Crossing Research Report (Photo 8)

By 1855, the Rappahannock Navigation Company was bankrupt. The Fredericksburg Water Power Company converted a portion of the navigation canal into a waterpower supply for mills in the city. The power company built a wooden crib dam across the river to divert a steady supply of water to the mills, then replaced that dam in 1910 with the taller concrete Embrey Dam. The waterpower canal still transported water from the river after 1910, but now it delivered it to the Embrey Power Plant. The hydropower plant generated electricity for approximately 50 years, before being shuttered in the 1960's.4

the Fredericksburg Water Power Company converted the Rappahannock Navigation Company canal into a delivery system for waterpower to mills

Source: Library of Congress, Military maps illustrating the operations of the armies of the Potomac and James against Richmond, May 4th, 1864 to April 9th, 1865 (1867?)

canal used to convey Rappahannock River water to Embrey Power Plant is still present in Fredericksburg

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Fredericksburg 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2010)

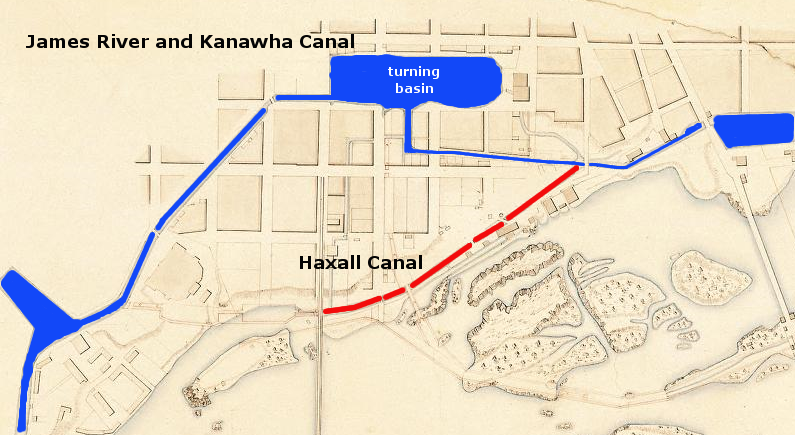

In Richmond, the transportation and power canals developed as parallel projects. George Washington, a strong advocate of transportation improvements that would link the Ohio River valley with port cities on the Atlantic coast, supported the James River Company's efforts to build a transportation canal that would bypass rapids and low water spots that affected shipping down the James River. Business leaders in Richmond built a second power canal closer to the river; the Haxall Canal provided waterpower to mills rather than transportation services.

James River and Kanawha Canal turning basin for canal boats (1841) is now James River Center in downtown Richmond

(separate Haxall Canal was used for power generation)

Source: Library of Virginia, Board of Public Works, Map of part of Richmond, Va., showing James River and Kanawha Canal

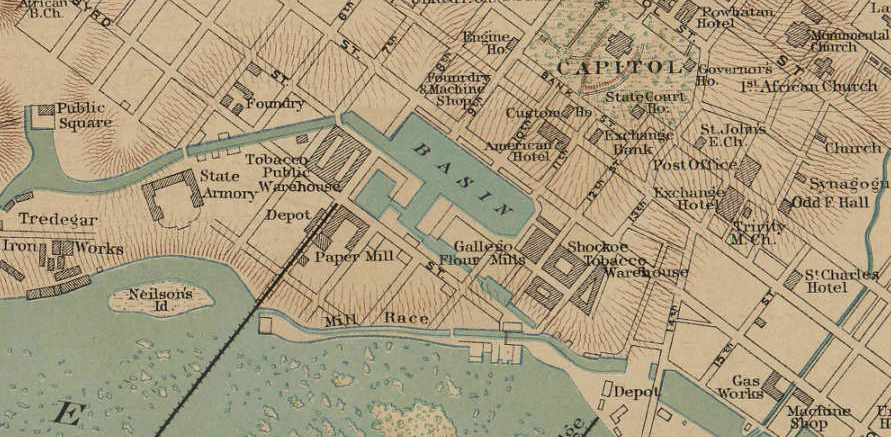

Richmond and Baltimore competed for the flour trade with South America, the Caribbean and Europe. Falling water from the James River turned many grindstones, and the Gallegos, Crenshaw, Haxall, and other flour mills made Richmond into a major manufacturing center prior to the Civil War.

parallel and close to the James River in Richmond, the Haxall Canal ("Mill Race" on the map) was used for power generation while the James River and Kanawha Canal carried cargo/passenger boats to the Turning Basin and on to the river, downstream of the Fall Line

Source: Baylor University's digital version of War of the Rebellion Atlas, Plate LXXXIX

Transportation canals were "internal improvements" that spurred intense regional rivalries in Virginia. Government approval of charters for canal corporations, and investment of public funds in specific canal projects, forced governors and members of the General Assembly to find a balance between support for canals in the James River vs. Potomac River watersheds.

The basic challenge was that river improvements would benefit just a narrow group of people who lived near a proposed canal project, or in the city to which the canal would steer trade. If government support for a transportation project made it easier to ship goods to Richmond, then Alexandria (and Petersburg, Fredericksburg, and Norfolk...) were jealous. Public funds spent to improve transportation in the Potomac River watershed did nothing to reduce transportation costs in the middle of the state; why should Nelson County taxpayers support a canal that would benefit farmers in Loudoun County or merchants in Alexandria?

The politicians solved the problem by supporting investment in "internal improvements" across the entire state.

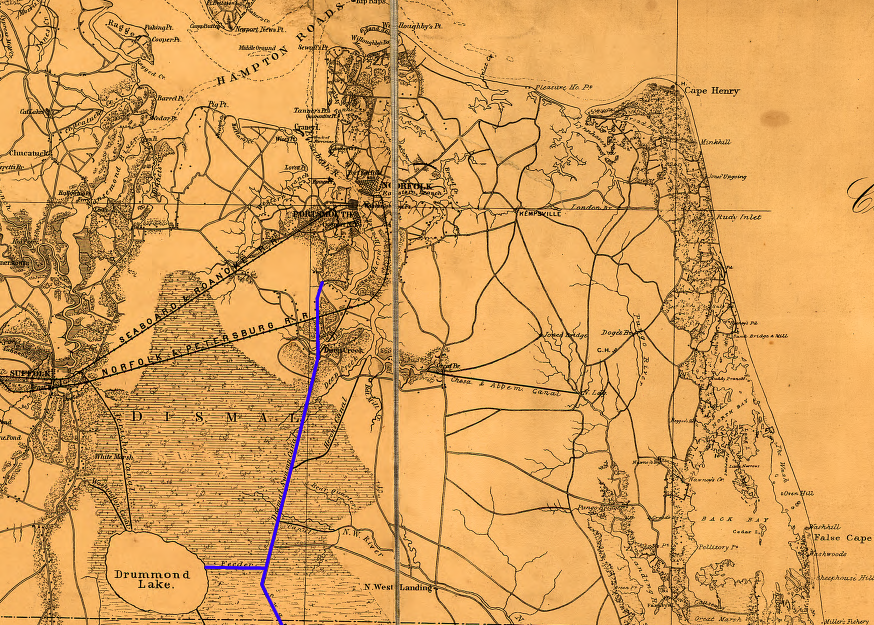

The Dismal Swamp Canal is the oldest operating canal in the United States, with traffic starting in 1804 and continuing today as part of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway. The canal benefited Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Suffolk, as well as farmers in North Carolina seeking access to the Chesapeake Bay ports. The canal crossed the watershed divide between the Elizabeth River and the Pasquotank River in North Carolina - but builders originally ignored the subtle topography. To maintain a water level high enough to float boats, locks were built near the Virginia/North Carolina line and a ditch was constructed westward to obtain water from slightly-higher Lake Drummond:5

Dismal Swamp canal in southeastern Virginia, 1862

Source: Library of Congress, Coast of North Carolina & Virginia (1862)

The General Assembly, through the Board of Public Works after 1816, bought stock in various transportation projects in an early version of "public-private partnerships." The state provided up to 60% of the financing for some projects.

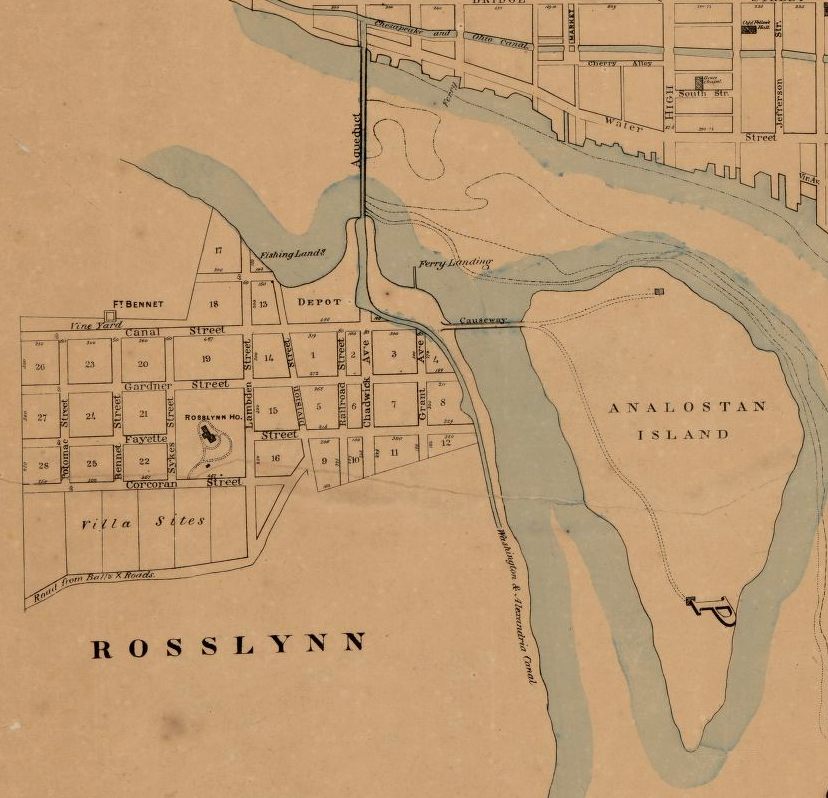

The state was less interested in Alexandria, which had been transferred to the Federal government in 1801 for inclusion within the District of Columbia. Town merchants had to finance, without Board of Public Works assistance, the construction of the Aqueduct Bridge and extension of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal to Alexandria.

The Alexandria Canal was constructed between 1841-43. Only in 1847, when Alexandria was "retroceded" back to Virginia, did the General Assembly agree to purchase Alexandria Canal bonds.6

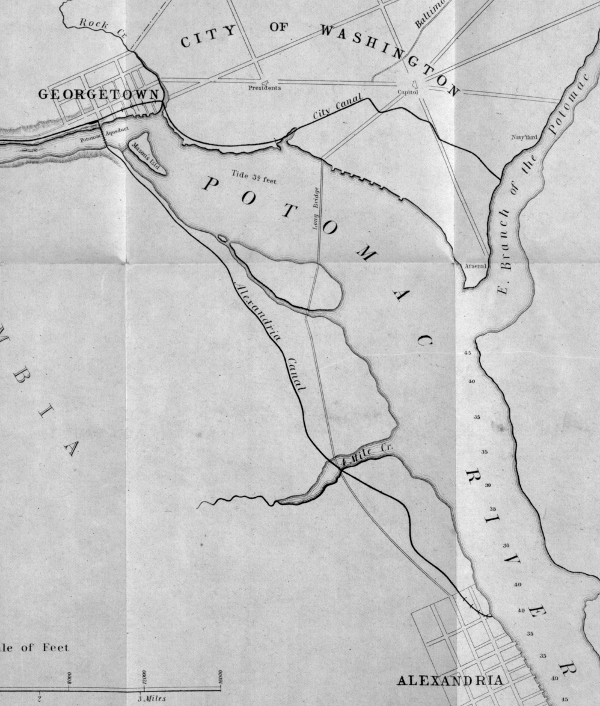

Alexandria merchants built the Aqueduct Bridge and Alexandria Canal in 1841-43 to compete with Georgetown merchants

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the city of Washington in the District of Columbia (William Forsyth, 1870) and Topographical map of the District of Columbia (by Albert Boschke, 1861)

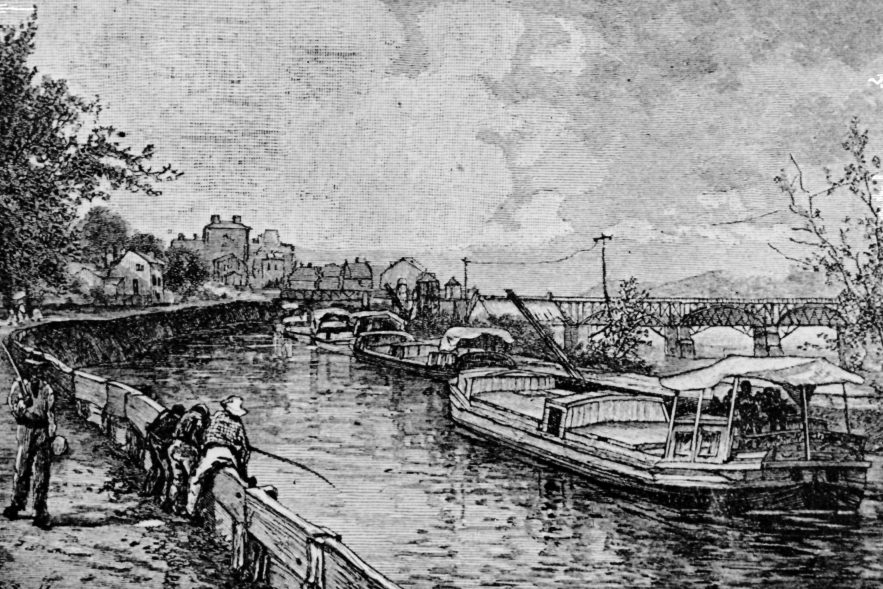

there was minimal water flow in canals, so boats were pulled by mules or pushed by poles

Source: National Park Service, Georgetown Historic Waterfront (Figure 50)

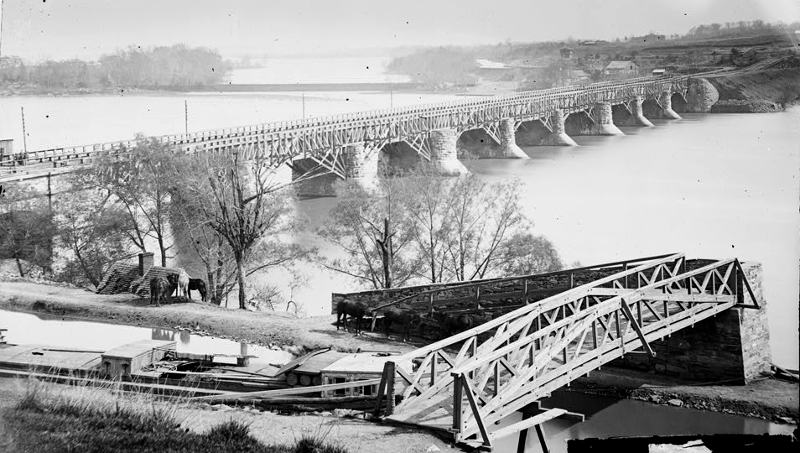

looking across Aqueduct Bridge to Arlington County during the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Closer view of Aqueduct Bridge, with Chesapeake and Ohio Canal in foreground

The upstream residents of the James River valley, and especially the citizens of Richmond, were the primary beneficiaries of the James River and Kanawha Canal project. Residents in Culpeper, Orange, and other upstream counties - and of course Fredericksburg - planned to gain from the Rappahannock River Canal. Enhancements to the Appomattox River would benefit Petersburg and the upstream residents in that watershed. The upstream residents in the Potomac River valley, plus the residents in Alexandria, would benefit from the Potowmack Canal and its successor, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal.

Canals were farm-to-market transportation systems, with the primary beneficiary being the port city at the downstream end. The most intense sectional rivalry affecting state investments in canals was between the communities in the James River watershed (with a canal terminating in Richmond) vs. those in the Potomac River watershed (with a canal terminating in Georgetown/Alexandria). Canals in both watersheds were designed to rival the Erie Canal in New York. Both were planned to connect with the Ohio River, so Midwestern farmers could do business with merchants in Virginia ports rather than with New York City.

The James River Company - and the later James River and Kanawha Canal - in the James River watershed provided no economic benefits directly to Virginians living near the Potomac River or the northern Shenandoah Valley. The Potowmac Canal - and the later Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal - in the Potomac River watershed helped farmers in the lower Shenandoah Valley and the merchants of Alexandria, but took potential business away from Richmond.

Watersheds of Virginia

Source: Department of Conservation and Recreation - Soil and Water

Conservation Programs

George Washington was an advocate for the Potomac River connection with the Ohio River, but he too felt obliged to express support for improving the James. The elected officials in Virginia balanced the state's investments in the two canals in the Potomac River and the James River watersheds. This created a sufficient coalition in the General Assembly to overcome resistance from others regions that would gain nothing, such as Tidewater plantations that already had easy access to transatlantic shipping.

George Washington in particular dreamed of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and other transportation projects uniting different sections of the new, still-fragile United States. He and his allies viewed canals as essential transportation improvements not only for reducing shipping costs for farmers east of the Alleghenies, but also for facilitating trading alliances with the new states that would be formed on the west side of the Appalachian Mountains.

After fighting in the Revolutionary War to create a new nation, Washington saw his new nation begin to fall apart under the Articles of Confederation. He risked his reputation to fight politically for ratification of the Constitution in 1787-88, but knew that geography shaped destiny. He feared that settlers in the Mississippi drainage would have minimal economic ties to the East Coast.

settlers west of the mountains could have chosen to form a new country and allied with Spain, so Washington sought to strengthen economic ties through construction of canals

Source: Library of Congress, The French and North America after the Treaty of Paris (1763-1803)

Washington wanted to ensure western settlers were economically connected to the Atlantic port cities, not linked to whatever nation controlled New Orleans and the trade route down the Ohio/Mississippi rivers. Trade across the watershed divide, between the Ohio River and Atlantic watersheds, would be limited by the mountain roads. However, canals would facilitate economic and political alliances, and enhance peaceful resolution of conflicts within the Federal system of the new United States.

The risk of dissolution, with settlers west of the mountains breaking away from the United States, was real. France and Spain claimed dominion in the Ohio River watershed by right of prior discovery. To the French, Louisiana had extended far up the Mississippi and "La Virgine" was restricted to land east of the Alleghenies.

The French had dreamed that their foreign military post at New Orleans would control Ohio River trade, since water transport was the most economical way to carry surplus products from farm to market. The British colonies along the Atlantic seaboard (and later the new country called the United States of America) might be limited to those lands east of the mountains.

The Spanish took over control of the Louisiana Territory from the French, and also challenged the American claim to lands east of the Mississippi River. Only after the 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo did Americans gain the "right of deposit" at New Orleans to ship products through the Spanish territory. New England leaders were willing to abandon the use of the Mississippi - and in the early 1800's, the head of the United States Army and Vice President Aaron Burr seriously schemed to steer the allegiance of western settlers to Spain and away from the United States. (Burr was tried in Richmond for treason related to his efforts.)

The intense debate over internal improvements and the National Road revolved around nationalism and sectionalism. In 1808, Albert Gallatin submitted his "Report on Roads and Canals." He proposed Federal financing- twenty million dollars over ten years - to support canals from the coastal plain to the interior. Gallatin recognized that the return on investment for private investment in canals might be too low, yet transportation improvements could stimulate additional projects connecting to a region, ultimately benefiting the general population even if the initial investors failed to make a profit:7

over-optimistic plans for the James River and Kanawha Canal included crossing the watershed divide between the James and Kanawha rivers, where the CSX Railroad now goes through the Allegheny Tunnel west of Covington

Source: Library of Virginia, Map of the survey of the summit level of the James River & Kanawha Canal

In 1817, President Madison vetoed the "Bonus Bill" of John C. Calhoun to use profits from the Second Bank of the United States for internal improvements. Madison recognized the value of canals and roads, but thought Federal financing would lead to too much Federal power:8

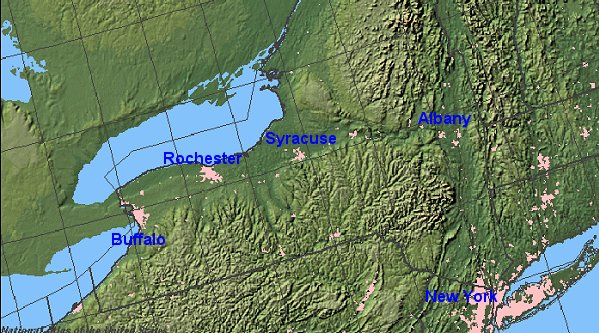

urban areas such as Buffalo developed along the Erie Canal

Source: National Atlas

In 1825, the Erie Canal linked the "Northwest" (Ohio to Wisconsin) with the Atlantic states north of Virginia. It had been financed by the state of New York, after Madison's veto of Federal support. The economic tie between New York City and the Old Northwest (Ohio, Indiana, Illinois - now the "Midwest") was reinforced by railroads prior to the Civil War. The success of the Erie Canal was an important part of the shift in economic and political power after 1820 away from Virginia and towards New York.

Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New Orleans were larger seaports than New York before construction of the Erie Canal. However:9

Virginia was the dominant member of the new United States from 1775-1800, with more people and a stronger economy than Pennsylvania or New York. However, in Pennsylvania the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Canal bypassed the Great Falls on the lower Susquehanna River in 1797, and in 1803 the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal was started to connect Philadelphia with the northern end of the Chesapeake Bay.

In New York, the Erie Canal connected the Hudson River valley with the Great Lakes in 1825, and by 1840 New York was the preeminent state in population and economic power. Virginia politicians mourned the decline of the state's importance and the state's residents continued to emigrate to new lands on the frontier, while Virginia floundered in its efforts to establish cheap transportation connections with the Ohio River. The Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal did not reach the Cumberland coal fields until 1850, by which time the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had already established the pattern where coal mines shipped their product to Baltimore.

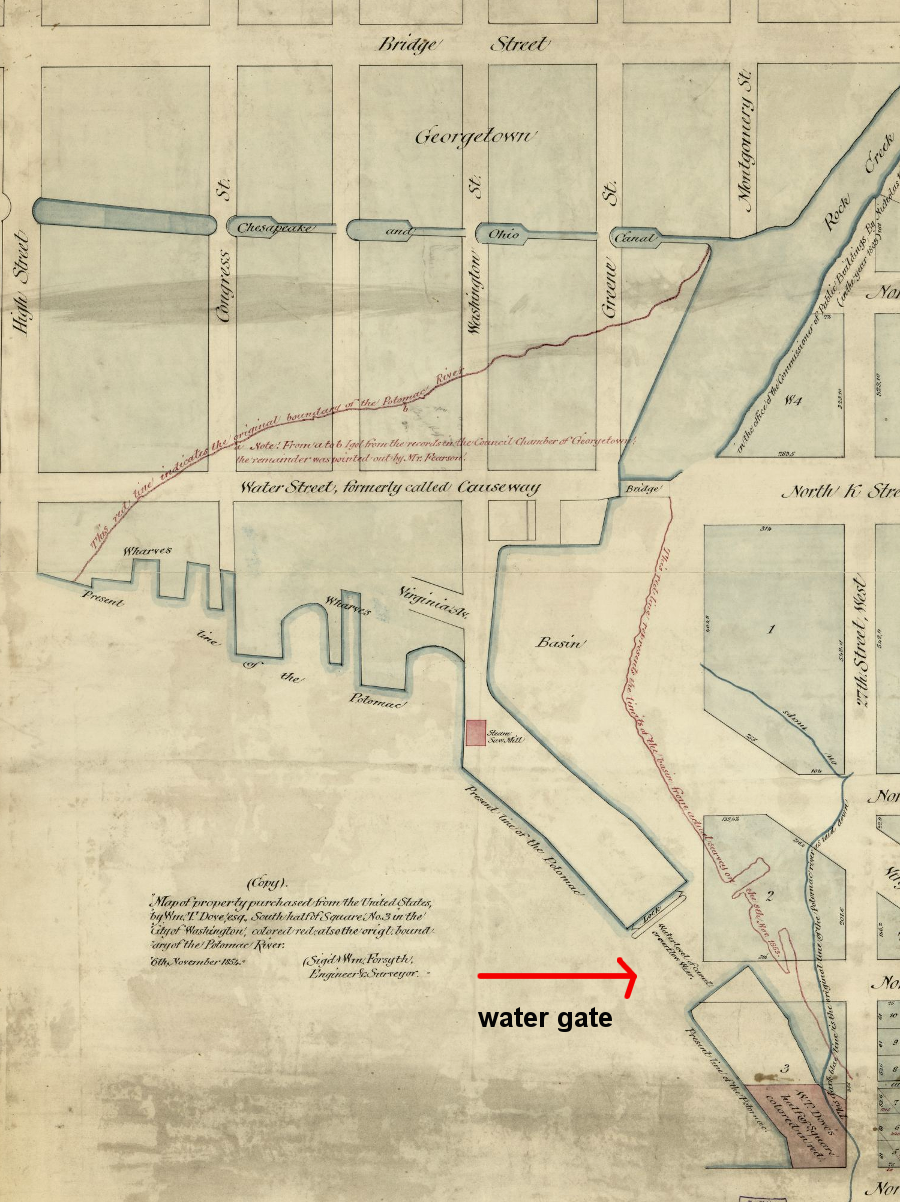

canal boats on the C&O Canal could enter the Potomac River via the water gate at the mouth of Rock Creek in Georgetown

Source: Library of Congress, Map of property purchased from the United States by Wm. T. Dove, Esq., south half of square no. 3 in the city of Washington (William Forsyth, 1854)

When the recession hit in 1857, followed by the Civil War, it became clear that Virginia had over-invested in too many money-loosing canal projects. Many partially-funded canals were never completed before a new technology - the railroad - provided a better/faster/cheaper alternative form of transportation. Virginia politicians failed to restrict state-sponsored infrastructure investment to just cost-effective projects. After the Civil War, the burden of the state debt would shape Virginia politics into the 1960's.

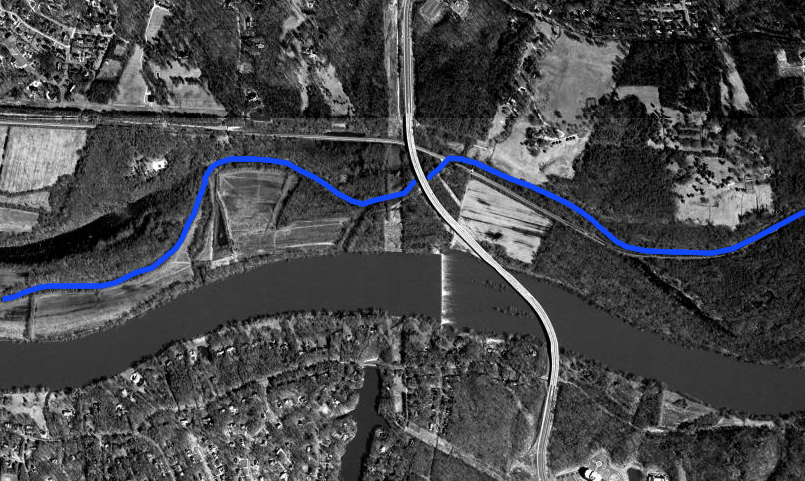

James River and Kanawha Canal route, at Willey Bridge/Bosher's Dam on James River

Source: Microsoft Research Maps

In the "what if?" category, imagine how Virginia might have evolved if the Potomac River or James River canal initiatives had been successful in reaching the Ohio River. Virginia might have retained its economic leadership - and the Civil War might have been averted. Though the Northwest Ordinance barred slavery from the territory, southern Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois were relatively supportive of the Confederacy because they were economically integrated with the slave economy of the southern states. Had trade from that "Old Northwest" region been aligned more with Virginia than with New York and Pennsylvania, there may have been no President Lincoln, no Civil War - and perhaps no 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments either...

in Richmond, the Tidewater Connection locks (downstream of the turning basin) linked the James River and Kanawha Canal to the navigable section of the James River below the Fall Line

Source: Library of Congress, Gardner's photographic sketchbook of the war

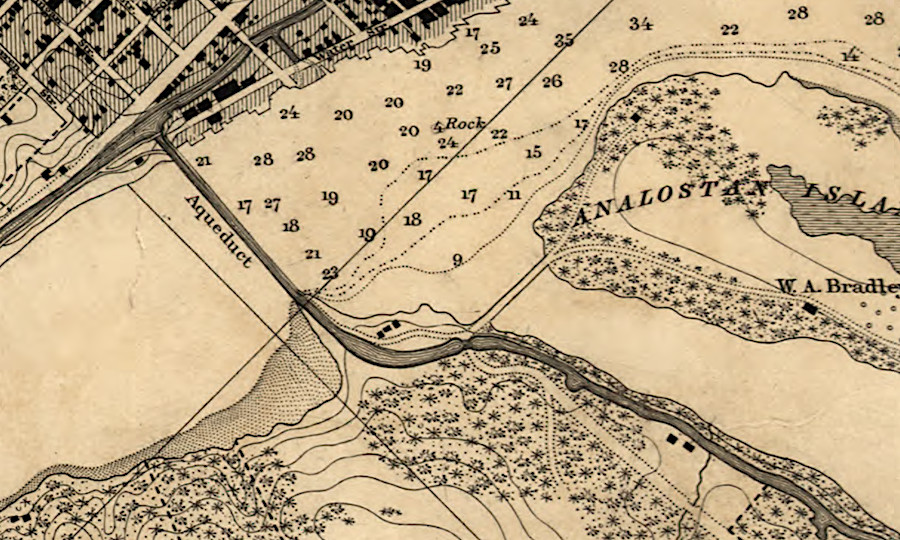

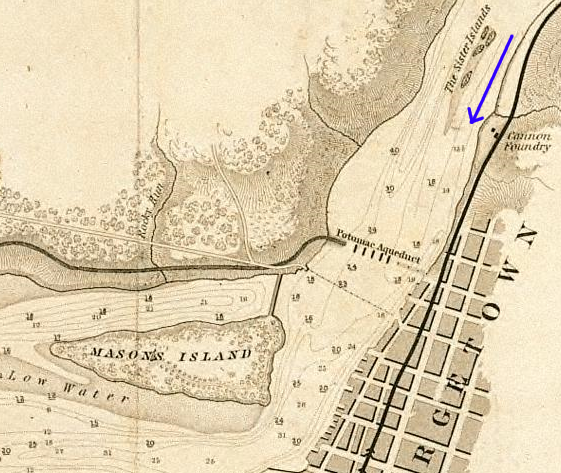

Aqueduct Bridge, where Alexandria Canal crossed the Potomac River - note Three Sisters islands (arrow shows flow downstream) (Mason Island is now "Teddy Roosevelt Island," where I-66 crosses into DC)

Source: Library of Virginia, Board of Public Works Inventory- Alexandria Canal Company

Alexandria Canal, stretching from Aqueduct Bridge at Rosslyn to Alexandria

(Analostan Island is now "Teddy Roosevelt Island," where I-66 crosses into DC)

Source: Library of Congress, G.M. Hopkins 1879 map -

Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington, including the counties of Fairfax and Alexandria, Virginia

Aqueduct Bridge at Rosslyn

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Alexandria County, Virginia for the Virginia Title Co. (Howell and Taylor civil & topographical engineers, 1900)

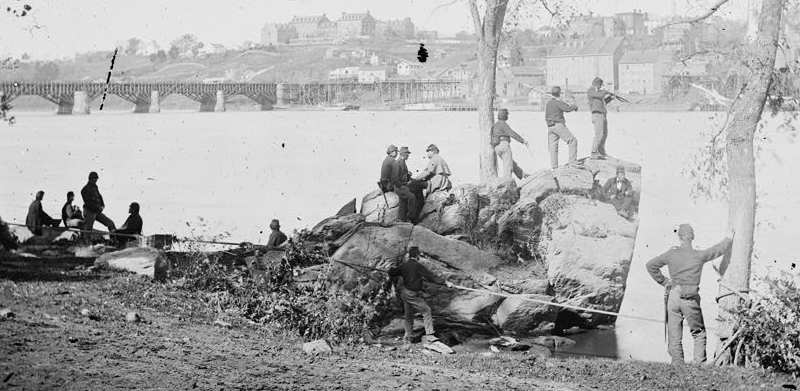

Aqueduct Bridge during Civil War, with Georgetown in background

Source: Library of Congress, Arlington, Virginia. Georgetown aqueduct from Virginia side of Potomac with Georgetown University in background

north of the Aqueduct Bridge, the Alexandria Canal connected to the C&O Canal and the City Canal

Source: Library of Congress, The water power at the Great Falls of the Potomac

reconstructed lock and gate on Chesapeake and Ohio Canal showing how water was released from canal to fill lock

remains of James River and Manchester Canal that once powered mills on south side of river at Richmond (and remains undeveloped for tourism today)

the Alexandria Canal included a water-filled bridge over Four Mile Run

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington, including the counties of Fairfax and Alexandria, Virginia