Getting Started Up the James

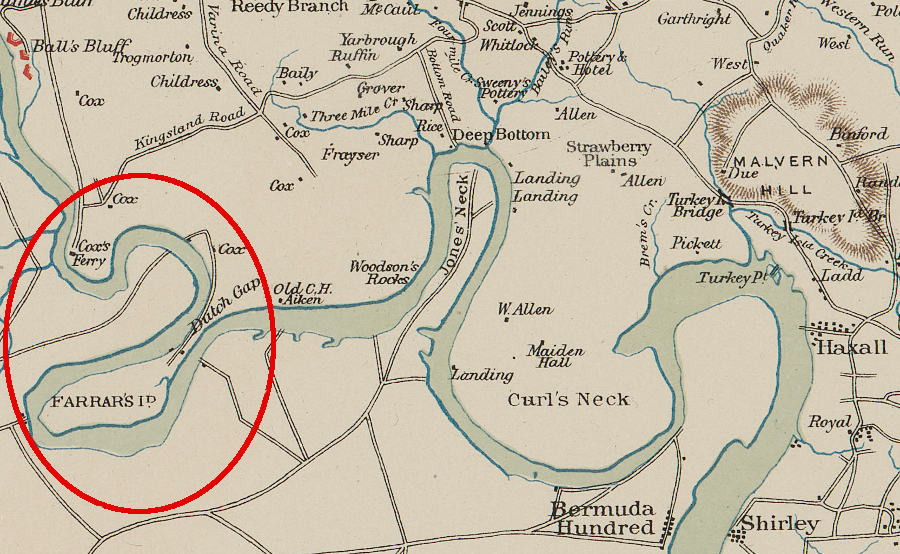

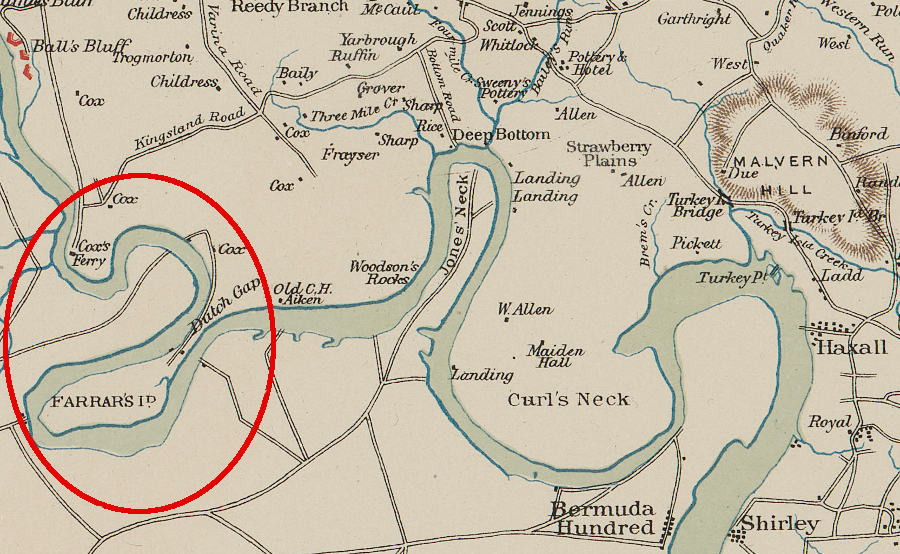

ships had to wind around Farrar's Island prior to construction of the Dutch Gap canal

Source: US War Department, Atlas to accompany the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, Southeastern Virginia and Fort Monroe Showing the Approaches to Richmond and Petersburg (1862)

On May 24, 1607, Christopher Newport rowed/sailed to the falls of the James River, where the river drops about 80 feet over six miles as the James River leaves the hard bedrock of the Piedmont and etches into the softer sediments of the Coastal Plain.

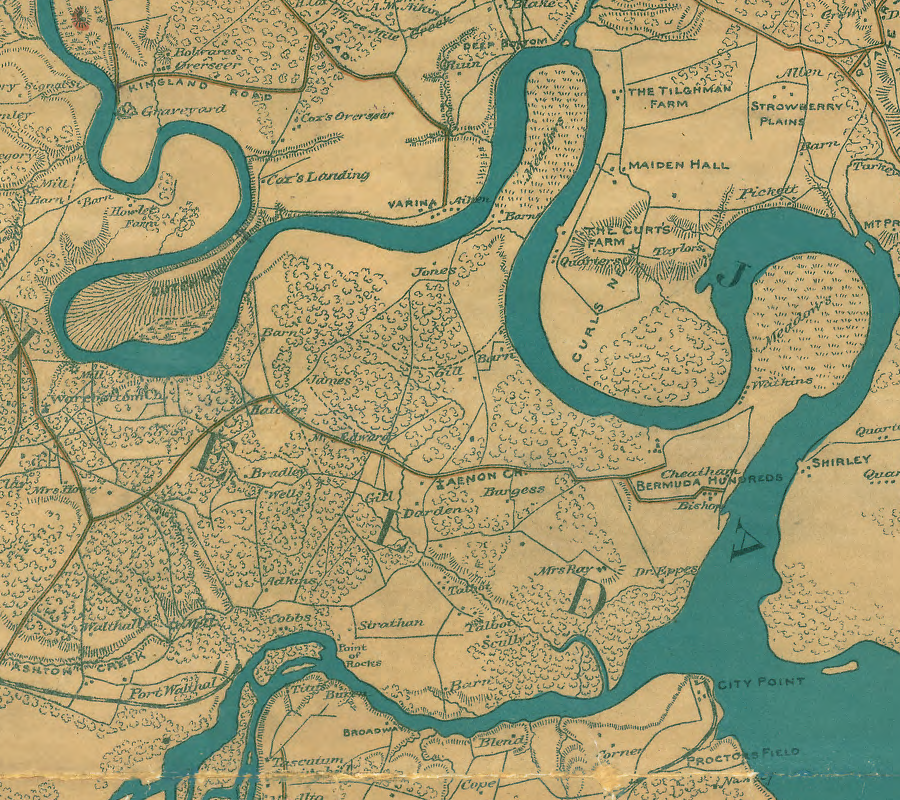

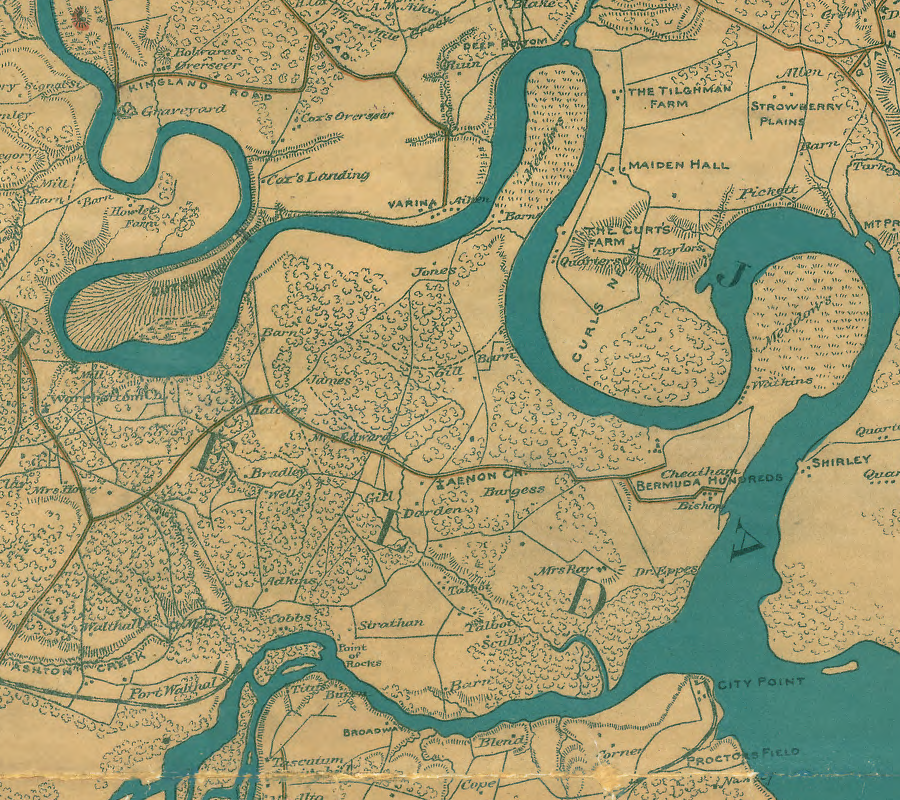

in 1607 Christopher Newport sailed/rowed around multiple necks as the English colonists went upstream from the Appomattox River to the Fall Line

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the vicinity of Richmond and part of the Peninsula (by T. Sewell Ball and Albert H. Campbell, 1864)

When Newport led an expedition upstream in September, 1608, he discovered the waterfalls stretched out for six miles, so he abandoned plans to carry a boat beyond the falls. The Europeans realized very quickly that travel into the interior would require the expense of loading/unloading ships to bypass the physical barrier to shipping.

James River rapids, looking upstream from Boulevard Bridge towards Belt Line railroad bridge and Powhite Parkway

Recognizing that the Fall Line would stimulate centers of human activity, William Byrd II laid out cities on the falls of the Appomattox and the James and named them Petersburg and Richmond in 1734. However, it took until 1772 before the House of Burgesses authorized a canal on the James so small boats could bypass the falls. Governor Spotswood had proposed connecting the James and Ohio Rivers way back in 1716, but Spotswood was a visionary.

It took another century of population growth before the colony could realistically finance or construct such a project. After a sufficient number of settlers had moved into the Piedmont and Shenandoah Valley, the costs of a canal could justified by the potential revenue from shipping (farm products downstream and manufactured goods upstream).

Almost 300 years after Gov. Spotswood, land use and transportation planners continue to debate where there is sufficient density to support new toll roads and transit infrastructure. Costs and benefits, if spread across enough users, might justify a new streetcar line along Columbia Pike or extending Metrorail to Prince William County.

However, unless a low-density suburb can establish high-density town centers, it is difficult to meet the cost-effectiveness criteria used to allocate funding to the highest-priority projects. Spotswood's problem has not disappeared; population density remains a key element in transportation planning.

portion of "Map of James River from Sabbot Island to Sydnor's Point"

Source: Library of Virginia, Board of Public Works Entry 495, Map #14

After 1772, John Ballendine took on the challenge of building the canal to bypass the falls at Richmond. Ballendine was an entrepreneur with more failures than business successes in his past. Not surprisingly, someone willing to tackle a new challenge had already risked - and experienced failure.

There are many parallels between Virginia's willingness to finance new transportation projects and the bubble of financing "dot.com" firms at the start of the 21st Century. Both involved transforming and old business model, and both stimulated new forms of creative financing followed by business mistakes, bad decisions regarding new technology, and bankruptcy.

Ballendine recognized that he knew very little about canal building, so he had the good sense to go to England, the world leader in such projects. There he studied the foundry business as well as canal construction, since his original business proposition was to use the canal's waterpower for industrial operations as well as for transportation. The falls of the James offered energy as well as a barrier to transport; Ballendine used the canal to take advantage of both aspects.

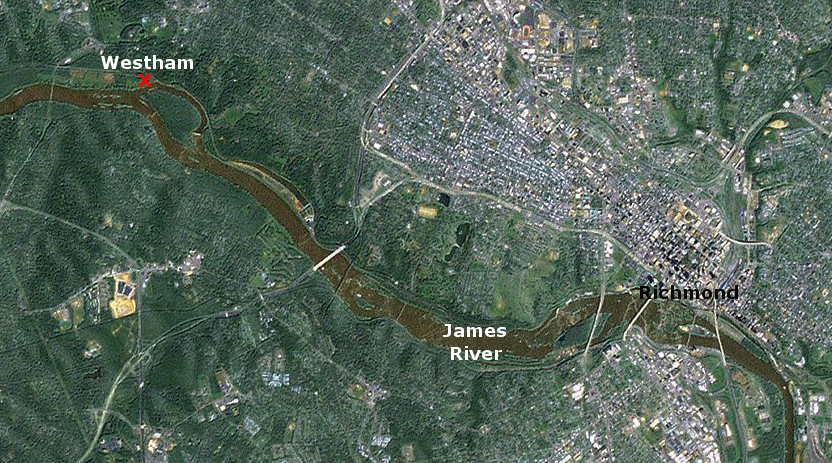

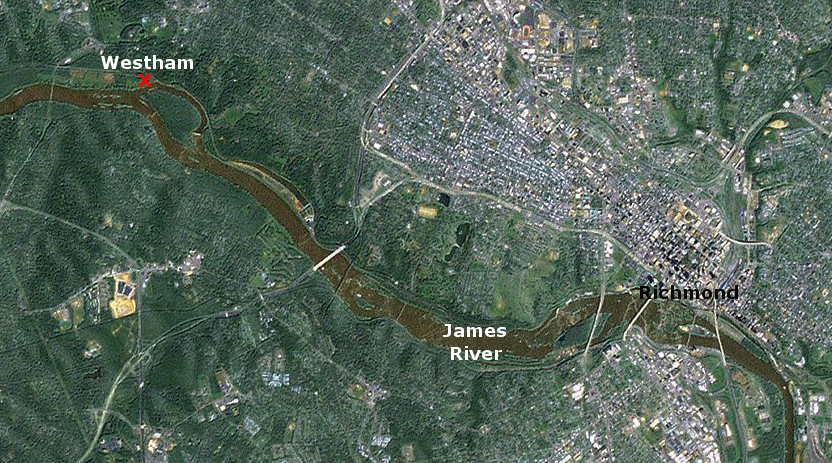

Westham foundry was above (west) of the Fall Line, reducing the hazards of shipping iron downstream from Buckingham County

Map Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

Ballendine planned to mine iron ore in Buckingham County, smelt it into "pigs," ship it down the James River to the upper end of the falls, then process the pig iron in a foundry in Richmond. The foundry was built at Westham, downstream from today's Huguenot Bridge, on the north bank of the James River opposite Williams Island.1

Why was a canal needed for a foundry? Water entered Ballendine's canal, upstream at today's Williams Dam. Perhaps 600 yards downstream, the water was released through a gate and dropped down onto a waterwheel.2

The falling water provided mechanical energy to turn the wheel. This energy was transmitted though belts and pulleys to the bellows and hammers in the foundry. The bellows were forced up and down, generating strong air flow through a forge. The extra oxygen heated the charcoal fire hot enough to melt the pigs, allowing the iron to be worked into shape or poured into molds. The hammers beat out the impurities in the iron, incorporated carbon into the metal, and pounded the iron into the shape required for various products.

Why build a canal to supply waterpower to a foundry at Richmond, rather than in Buckingham County?

Perhaps the small drop of elevation at Bremo Bluff and other locations on the river upstream did not provide a sufficient hydraulic "head" to power the waterwheel without building an excessively long millrace. Perhaps there was not enough available skilled labor upstream to operate a foundry. Perhaps Ballendine preferred to locate his manufacturing plant closer to the market, so he could adapt production to fit the latest reports of demand and have the option of shipping to Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Charleston, or the Caribbean.

Buckingham County is upstream from Westham, and Westham is upstream from the original site of Richmond at the Fall Line

Map Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

Ballendine never came close to fulfilling his promises to the General Assembly, so perhaps he might have been inclined to locate his operation out of sight, in the backcountry far away from prying eyes. The leaders in the colony knew that a canal at Richmond would be insufficient to open the James, and an initiative in 1774 had proposed removing obstructions in Buckingham County at Seven Islands, near the mouth of the Hardware River.

For whatever reason, Ballendine chose to take advantage of the General Assembly's support for a canal at Richmond and purchased 50 acres for a foundry. That political support continued even after the colonial government was dissolved in 1774. The Virginia Convention (the revolutionary body that met 5 times between 1774-1776 to govern Virginia before it adopted a state constitution) loaned Ballendine enough money in 1776 to buy 3,000 acres in Buckingham.

The foundry did produce kitchen tools and - far more important to the new General Assembly - cannon for the Revolutionary War effort. In January, 1781, Benedict Arnold and his British cavalry under Col. Simcoe caught Gov. Thomas Jefferson and the local militia off guard. The foundry was destroyed and the materials dumped into the river.

Dutch Gap Canal

Source: National Archives, Virginia - Dutch Gap Canal (1933 or earlier)

the Manchester Canal, completed around 1800, provided waterpower for industries located at the Fall Line on the south bank of the James River

Source: Library of Virginia, The Bibliography of a Map

Links

References

1. "John Ballendine to Cary Archibald, Edward Carrington, and James Southall, July 12, 1779, Contracts for Iron Works at Westham, Buckingham Furnace, Canal, and Dam," The Thomas Jefferson Papers at the Library of Congress, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mtj.mtjbib000353 (last checked October 6, 2012)

2. Gibson, Langhorne Jr., Cabell's Canal: The Story of the James River and Kanawha, Commodore Press, Richmond, 2000, p. 19

Canals of Virginia

From Feet to Space: Transportation in Virginia

Virginia Places