The First Canal, at Williamsburg

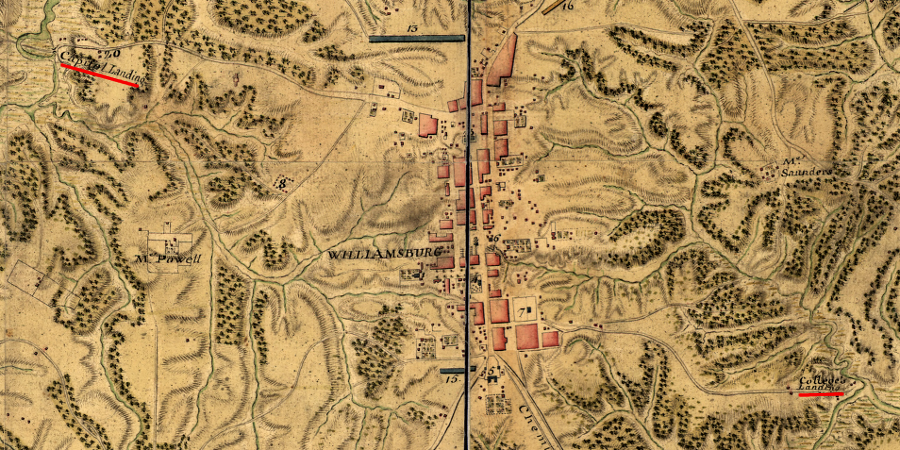

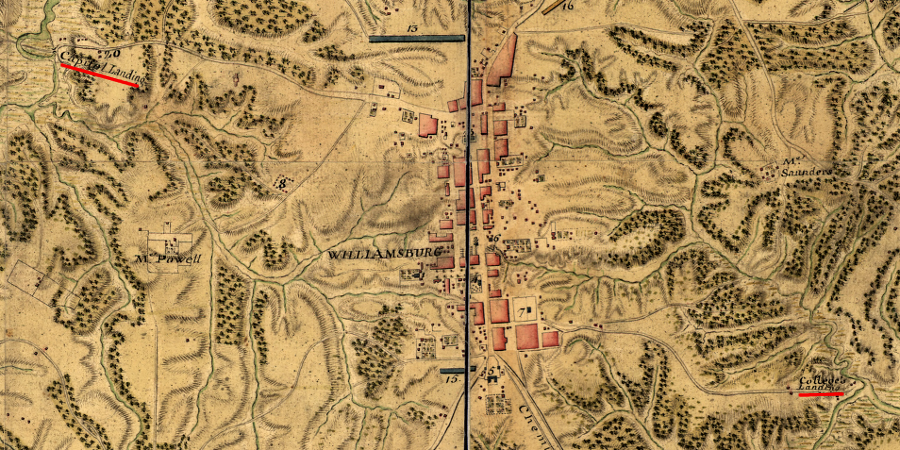

French military engineers at Williamsburg documented the locations of Capitol Landing (access to the York River) and College Landing (access to the James River) in 1782

Source: Library of Congress, Armée de Rochambeau, 1782. Carte des environs de Williamsburg en Virginie où les armées françoise et américaine ont campés en Septembre 1781

Virginia was integrated into the international economy from the very beginning. Early explorers sailed into the Chesapeake looking for the Northwest Passage to China and the spice trade of Indonesia. When Virginia became a destination for European settlers rather than an obstacle for explorers, the colony stayed dependent upon Europe for essential goods - even food - until 1611. Settlers in Jamestown relied upon "resupply" shipments financed by the Virginia Company, until the tobacco trade created an economic foundation for the new colony and strong leaders (some using the powers of martial law) ensured sufficient food was grown to meet local requirements.

Transatlantic shipping was colonial Virginia's primary means of transporting farm products, animal skins, lumber, and other goods. Virginia was on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean from Europe - but Virginia was never inaccessible. In the mercantile economy of the 1600's and 1700's, the easy transportation of raw products and manufactured goods across the ocean shaped the economy. Few items were manufactured in the colony. Farm tools, glasses, rugs, books, wine, even the cloth used for slave clothing was shipped from overseas. Bulky raw goods (tobacco, cedar shakes, furs) were sent from the colony to Europe, and high-value manufactured goods were shipped to Virginia in return. Almost everything traveled by ship. Plantation wharves (and the docks in "tobacco towns" after 1730) were the economic centers of the colony.

a water feature behind the reconstructed Governor's Palace in Williamsburg serves as a reminder of the proposed canal

After the colonial capital moved in 1699 from Jamestown to Williamsburg ("Middle Plantation"), the biggest city in the colony was inland on a ridgeline, on the watershed divide separating the James and the York rivers.

The shift to Williamsburg moved the capital away from the threat of Dutch, French, or Spanish attack, and closer to the inland settlements. The new location was also away from swamps and the brackish water of Jamestown, with the diseases that they brought. However, moving away from the swamps meant wagons and horses had to carry goods and people from the riverbank to the town.

The road to Hampton followed the high point of land that drained most quickly after a rain, but the "improved" roads around Williamsburg were still dirt roads full of mudholes and ruts. Shifting items from ships at Yorktown into wagons added substantially to the cost of supplying the capital.

As population increased to the north and west of Wlliansburg, there were multiple proposals to move the colonial capital to a port city further upstream on the Pamunkey or James rivers. After the Capitol building burned in 1747, relocation was approved several times by the House of Burgesses but vetoed by the Council or officials in London.

Supporters of staying in Williamsburg recognized that the shifting pattern of population would steadily increase pressure to move the seat of government further inland. In 1772, the House of Burgesses considered the issue for the third time in the last decade and voted by 48-32 to move, with Bermuda Hundred on the James River as a likely location.

To make Williamsburg more attractive, Lord Dunmore announced in 1771 that a canal would be constructed to connect Williamsburg with both the York and James rivers. It would run from the headwaters of Archer's Hope Creek on the James River (now College Creek) to the headwaters of Queen's Creek on the York River, overcoming 80 feet of topographic relief.

The General Assembly approved the canal in 1772, but appropriated no funding. The onset of the American Revolution led to abolition of the appointed Governor's Council and replacement by a State Senate, with representatives from areas far from Williamsburg. In 1780, the General Assembly finally approved the move of the capital, and the primary reason for building a canal at Williamsburg evaporated.1

possible route of 1781 canal (see route that presumably was rejected)

Source: Alexander Crosby Brown, Colonial Williamsburg's Canal Scheme

(overlayed on USGS 7.5 minute topo, 2010)

A later proposal in 1818 to build a similar water link, from College Creek to the York County Courthouse, also remained just on paper. The Peninsula was never converted to an island, and no boats ever reached the back of the Governor's Palace from the York or James rivers.

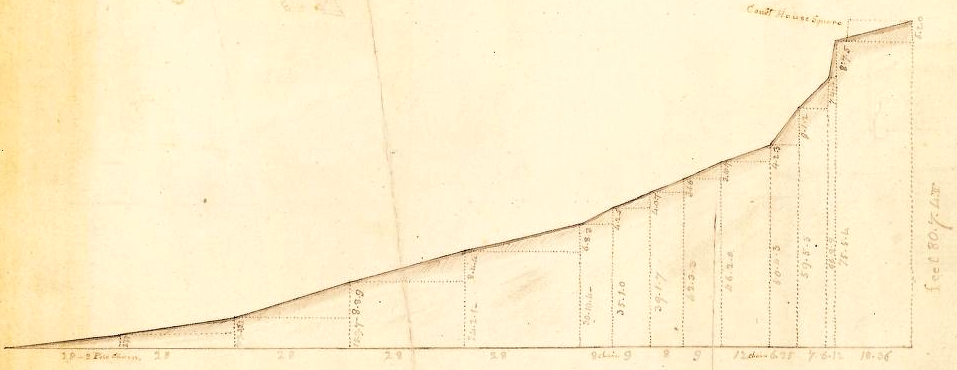

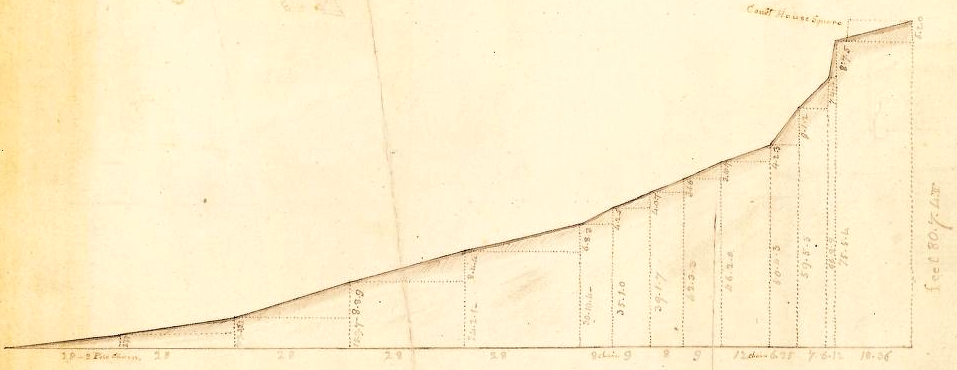

1818 engineering diagram showing elevation change for canal to Williamsburg, based on 1771 proposal

Source: Library of Virginia, Profile of the Virginia canal from tidewater to Williamsburg

References

1. Alexander Crosby Brown, "Colonial Williamsburg's Canal Scheme," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography,

Vol. 86, No. 1 (Jan., 1978), pp. 26-32, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4248181; Alonzo T. Dill and Brent Tartar, "The 'hellish Scheme' to Move the Capital," Virginia Cavalcade, v.33, No.1, Summer 1980, pp.4-11, http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/cavalcade/volumes/v21_30/sum80.htm (last checked February 2, 2017)

Canals of Virginia

From Feet to Space: Transportation in Virginia

Virginia Places