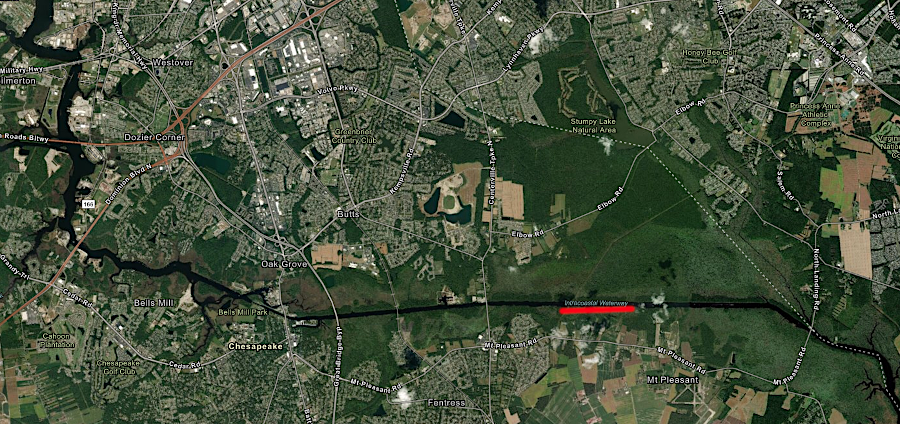

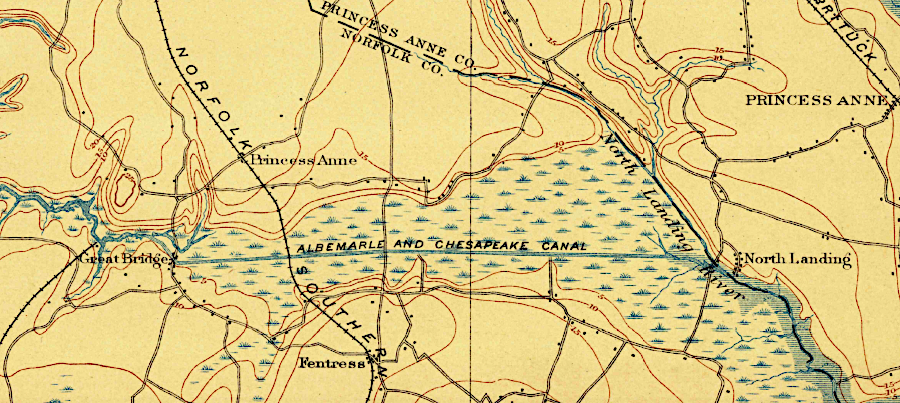

the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal linked the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River to the North Landing River in 1859

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal linked the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River to the North Landing River in 1859

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

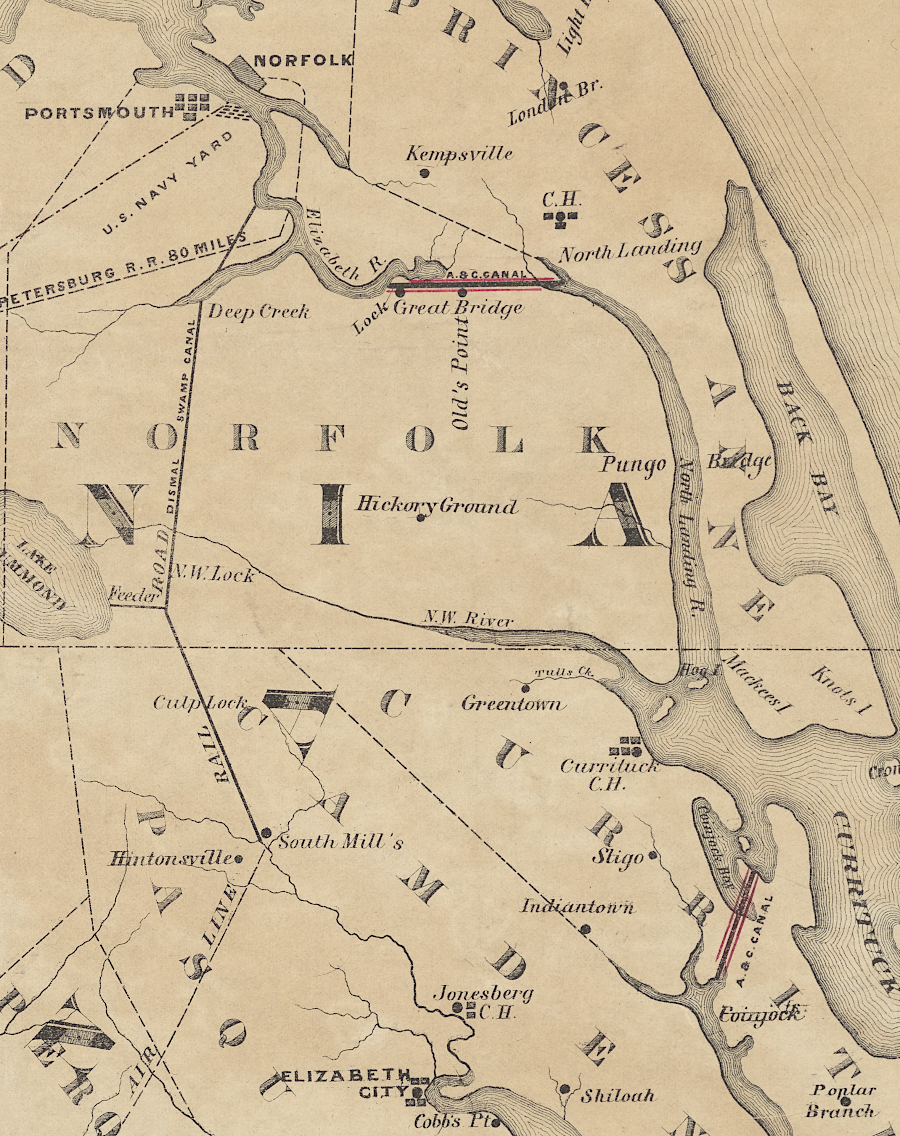

William Byrd II recognized in 1728 that a canal could close the short gap between the North Landing River and the Elizabeth River, allowing boats to carry freight and passengers between Currituck Sound in North Carolina and the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia. The Virginia General Assembly first considered that route for a canal proposal in 1772.

However, the two states cooperated first to build the Dismal Swamp Canal, further east near the land owned by the influential members of the Dismal Swamp Land Company. That rival transportation corridor linking the Pasquotank and Elizabeth rivers opened in 1805. The legislatures in both Virginia and North Carolina authorized a North Landing River-Elizabeth River canal ten times before it was finally constructed.

In 1850, the Great Bridge Lumber and Canal Company was chartered by Virginia to restart the proposed canal connecting the North Landing River and the Elizabeth River. The company merged with a North Carolina equivalent in 1856 and was renamed the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal Company.

A businessman in Norfolk, Marshall Parks, was a major advocate for the new canal. His father had been manager of the Dismal Swamp Canal, and he knew its shortcomings well. The Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal would be significantly deeper, allowing larger steam-powered ships to pass through.

It would also have only one set of locks. By that time, the Dismal Swamp Canal had seven locks to manage water levels, but each one added delay to the trip.

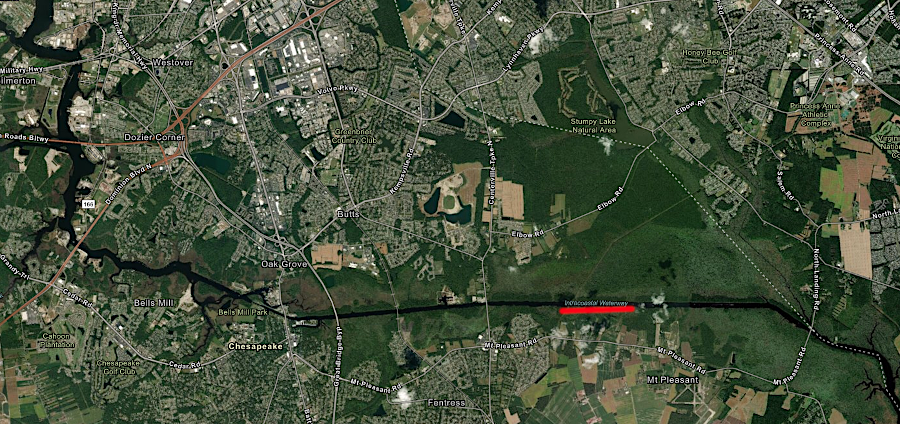

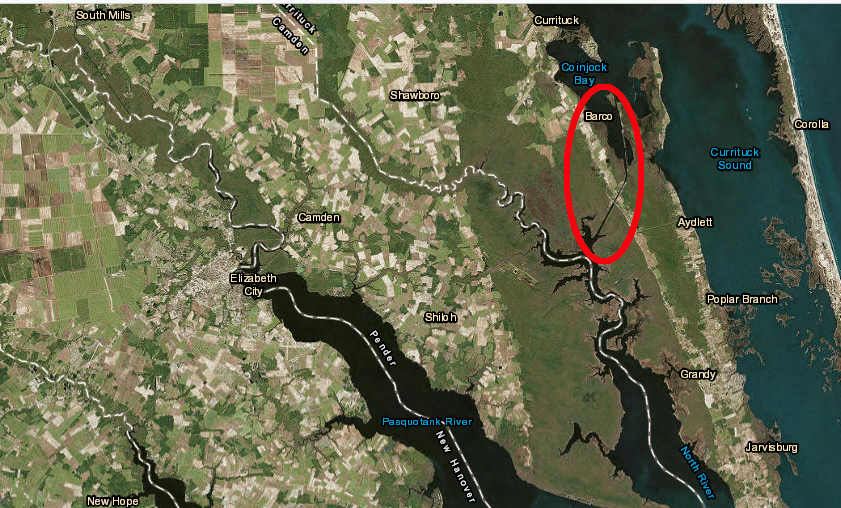

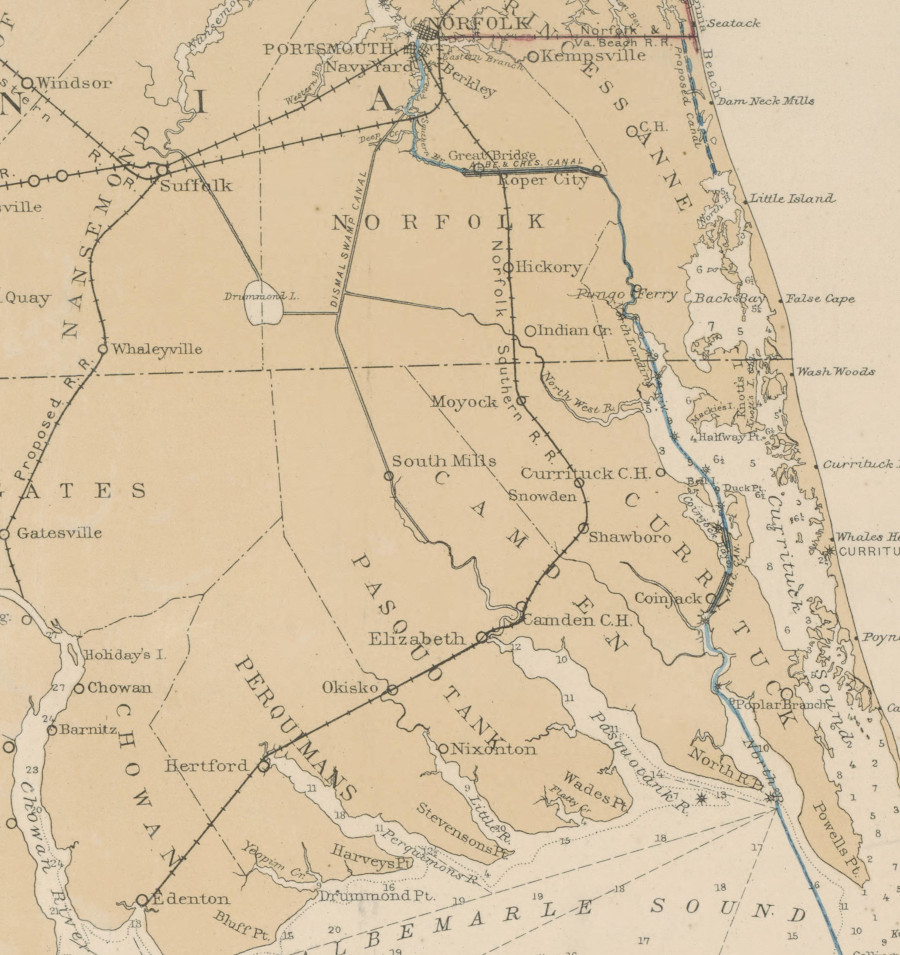

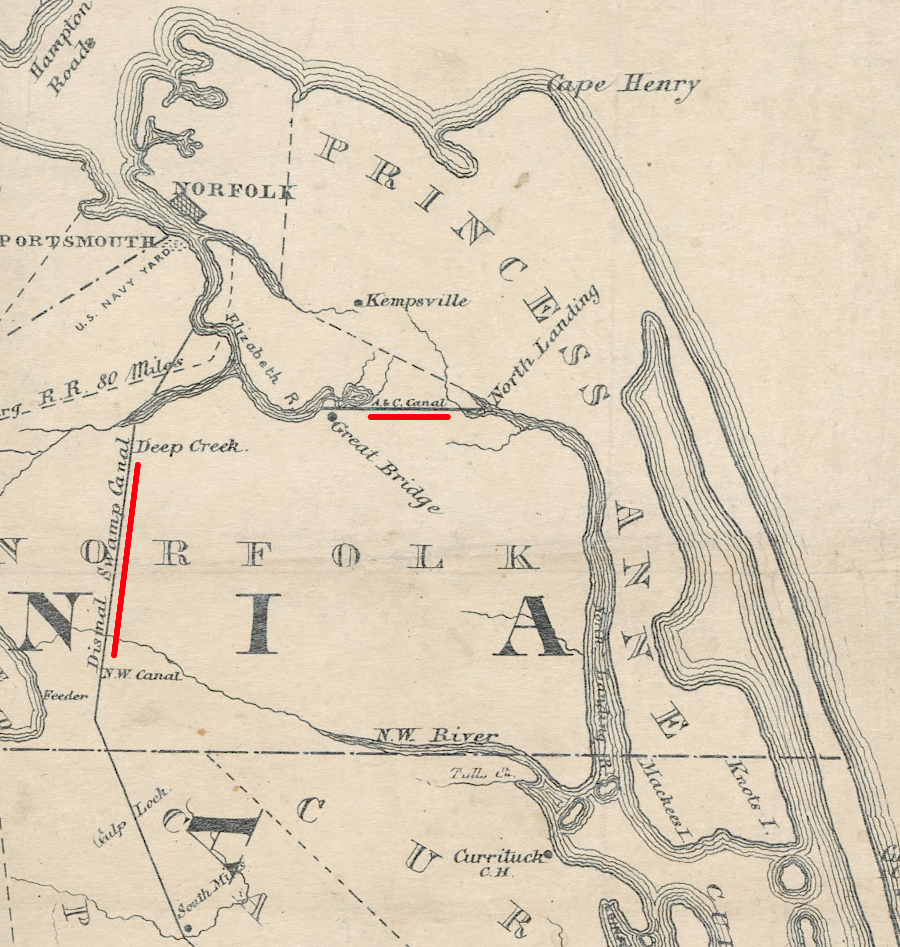

Two routes were considered for the new connection to the North Landing River. The company considered cutting a ditch between the Eastern Branch of the Elizabeth River at Kempsville before choosing the alternative route, a link from the headwaters of the South Branch of the Elizabeth River.

the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal could have connected to the Eastern Branch of the Elizabeth River, but was built in 1859 to the Southern Branch

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the state of Virginia (by Lewis Von Buchholtz, L. V., Herman Böÿe, Benjamin Tanner, 1859) and ESRI, ArcGIS Online

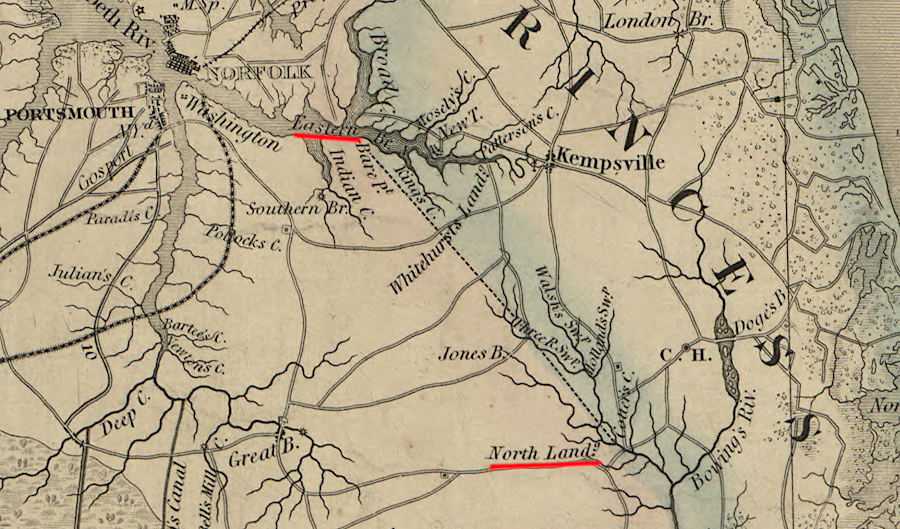

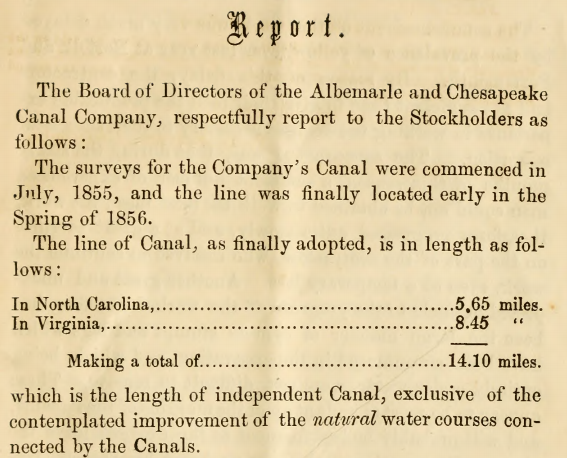

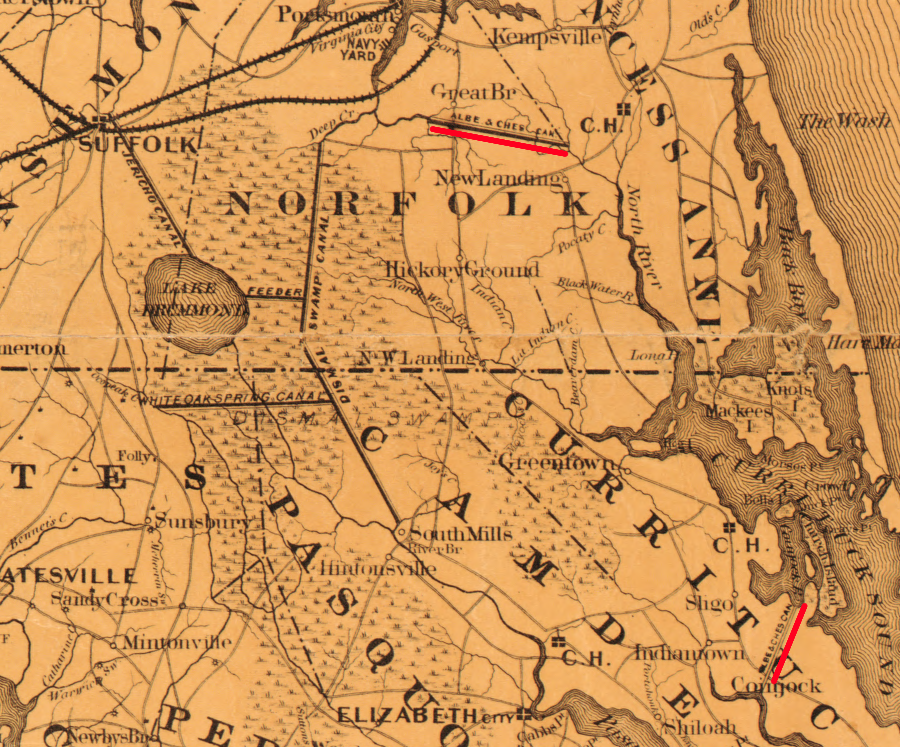

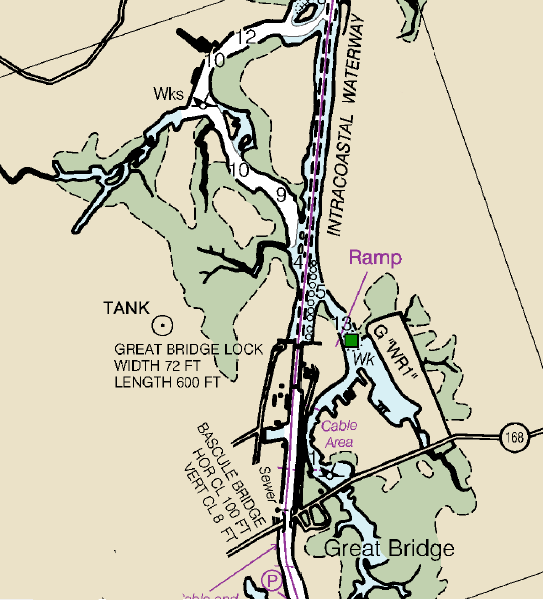

Construction of the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal required three years before it opened in 1859. The 8.45-mile channel between Great Bridge on the tidal Elizabeth River and the fresh waters of the North Landing River was 40' wide and 8' deep. Wind in the Currituck Sound as well as lunar-driven tidal changes determined the water levels at the North River Landing end. High and low tides occurred at different times at the Great Bridge end, so a 220-foot lock was built there in 1856-59 to maintain water levels. Typically ware levels were equal four times daily, so the gates of the lock could be left open and ships experienced no delay.

Great Bridge Lock at Battlefield Boulevard, and looking east on Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal

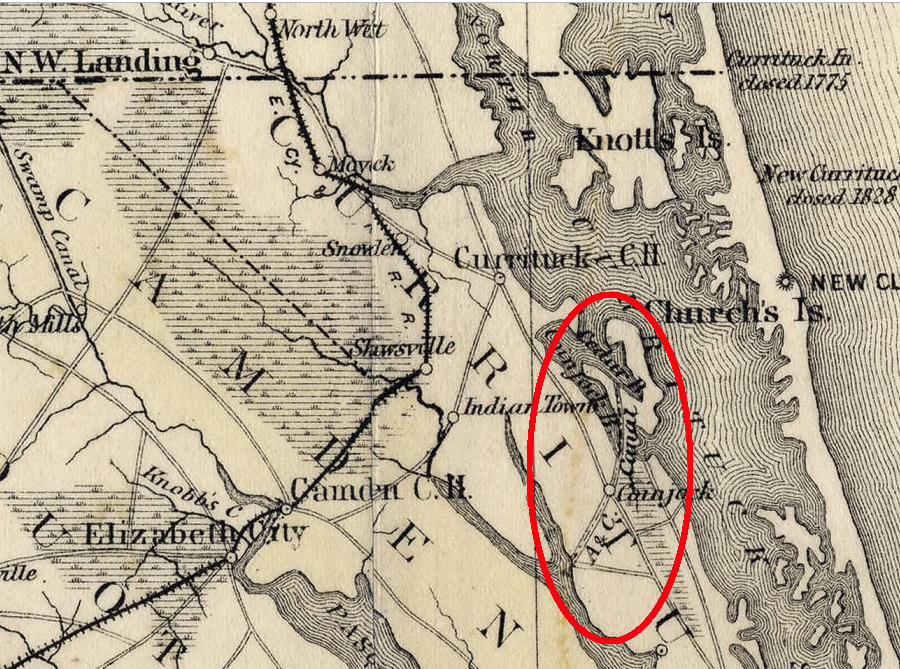

A second 5.65-mile channel was excavated in North Carolina between Coinjock Bay of Currituck Sound and the North River.

the first annual report of the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal Company identified the length of canal segments

Source: Internet Archive, Annual report of the President and Directors of the Albemarle & Chesapeake Canal Company

Nine steam dredges excavated the canals, but construction still required some back-breaking hand labor to move muck and sunken logs. The Virginia Cut channel was sometimes called the Juniper Cut, reflecting the large number of cypress tree roots dredged out of that channel. The stumps and logs caused "great and vexatious delays."

The dredges reduced the need for hiring workers, but during the "sickly months" the machinery was not fully utilized because experienced labor was scarce.

The canal also included improvements to the shipping channel in the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River, North Landing River, Currituck Sound, and North River. The total 55 mile length of the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal included 41 miles of river improvements and 14 miles of newly-excavated canal channel.1

the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal included the North Carolina (Coinjock) Cut linking Coinjock Bay of Currituck Sound with the North River

Source: University of North Carolina, Map of North Carolina (by Washington C. Kerr, 1882)

Coinjock Cut on the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal today

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The private Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal Company acquired a strip of land 280-feet wide, excavated an 40-foot wide canal, and opened it for business on January 9, 1859. The canal was designed for steamboats to provide their own power to move; no towpath was built parallel to the water.

The canal diverged from the natural river channel at the site of the Revolutionary War Battle of Great Bridge. Construction there in 1859 destroyed the remains of the 1775 and 1781 forts and the historic causeway across the channel.

The 220-foot long original lock at Great Bridge kept water levels even as the tides affected the Elizabeth River, and blocked currents from flowing through the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal. When the canal was widened to 80 feet in 1913-1917, the Great Bridge lock was removed. Federal funding to build a 600-foot long replacement was provided in the Great Depression, and the current lock was completed in 1932.

At the start of the Civil War, the Confederate forces controlled the canal. After Norfolk was captured in May, 1862, Union forces remained in control for the rest of the war. It was re-opened to traffic in May 1863, but the wooden drawbridge over the canal at Great Bridge was not replaced until 1868.

Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal in 1861, with cuts excavated in Virginia and North Carolina

Source: Library of Congress, Colton's new topographical map of the eastern portion of the state of North Carolina with part of Virginia & South Carolina (by Joseph H. Colton, 1861)

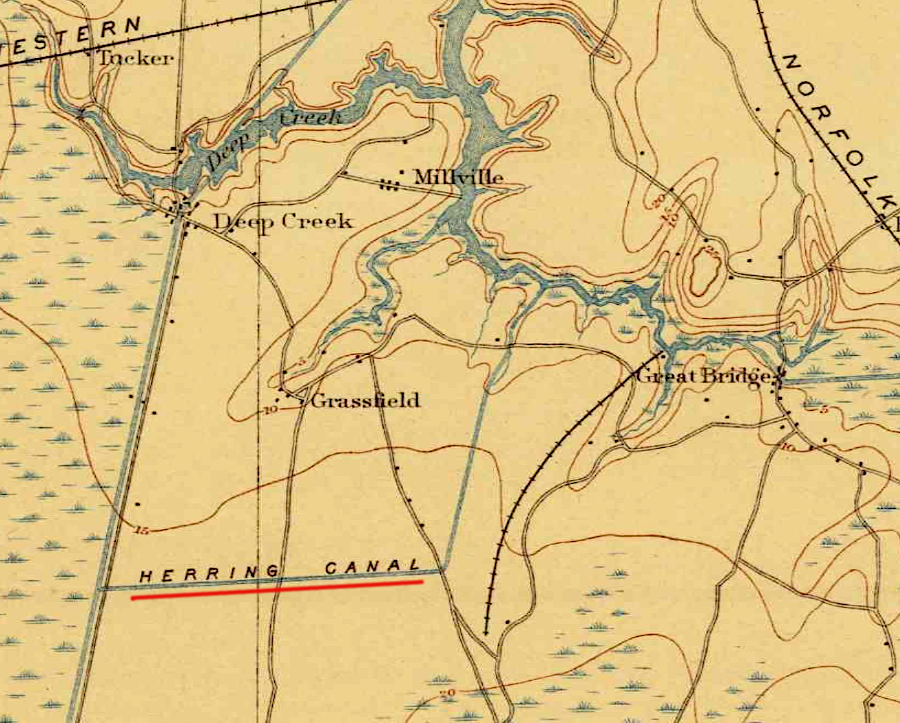

The Dismal Swamp Canal provided some competition. Walter Herron's ditch, dug in the 1820's to move timber and shingles to the Dismal Swamp Canal, was extended to the South Branch of the Elizabeth River. What became known as the Herring Canal provided a shortcut between the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal and the Dismal Swamp Canal until construction of US 17 blocked it in the 1920's.

The biggest business threat came from railroads after the Civil War. While at least one track in the swamplands brought timber products north the South Branch of the Elizabeth River rather than to the Dismal Swamp Canal, other lines eliminated the need for water transport.

Herring Canal connected the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal and the Dismal Swamp Canal until the 1920's

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Norfolk VA 1:125,000 topographic quadrangle (1902)

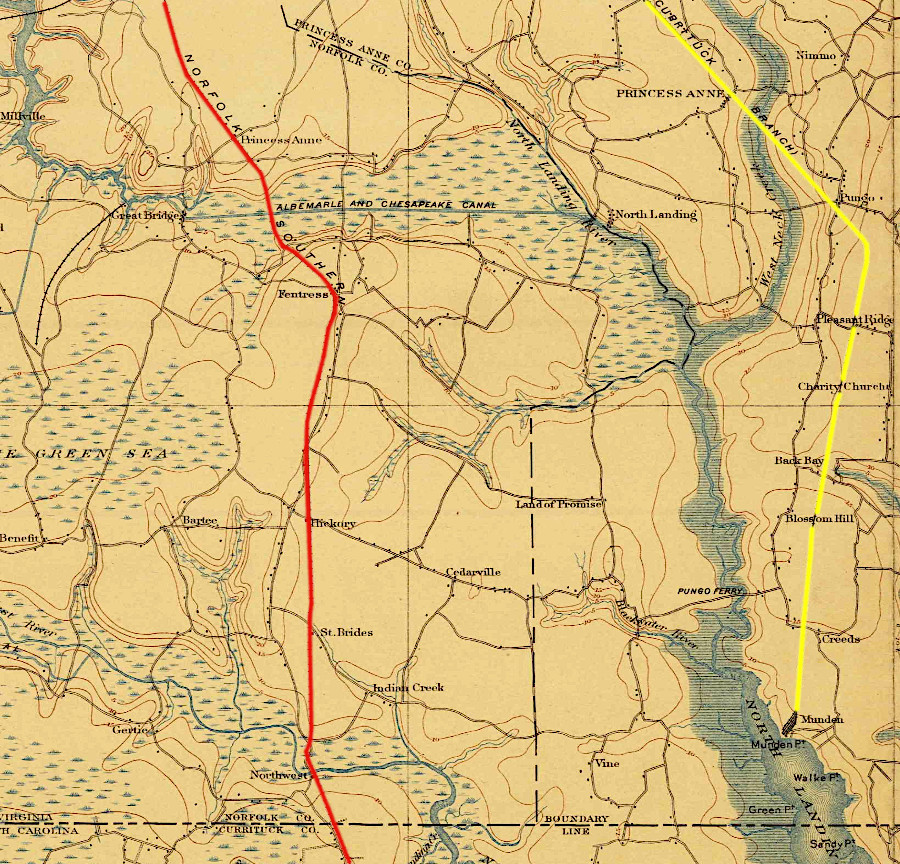

The Elizabeth City & Norfolk Railroad (later the "original" Norfolk Southern Railroad) built the only railroad bridge across the canal. The first bridge, constructed in 1880, was replaced by the current bridge in 1928 when the canal's width was doubled to 80 feet. The main line of the Norfolk Southern Railroad and its Currituck Branch paralleled the North Landing River on either side, offering lower-cost transportation to Norfolk.

the Norfolk Southern Railroad (red) and its Currituck Branch (yellow) paralleled the North Landing River on either side, competing with the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Norfolk VA 1:125,000 topographic quadrangle (1902)

New ownership of the Dismal Swamp Canal in 1892 led to its renovation in 1896-1899. The competition drew trade away from the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal for the first time. It had received tolls on 403,017 tons of freight in 1890, but that dropped to 95,169 tons in 1906.

Business declined, and the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal went bankrupt in 1910. In the 1910 River and Harbor Act the US Congress authorized the Department of the Army to acquire it, so the US Army Corps of Engineers could incorporate that canal into the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway.

The Federal government purchased the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal in 1913. It dredged the canal to a nine-foot depth and 50-foot width, and eliminated the tolls. Once again it out-competed the Dismal Swamp Canal, which the Federal government finally purchased in 1929.2

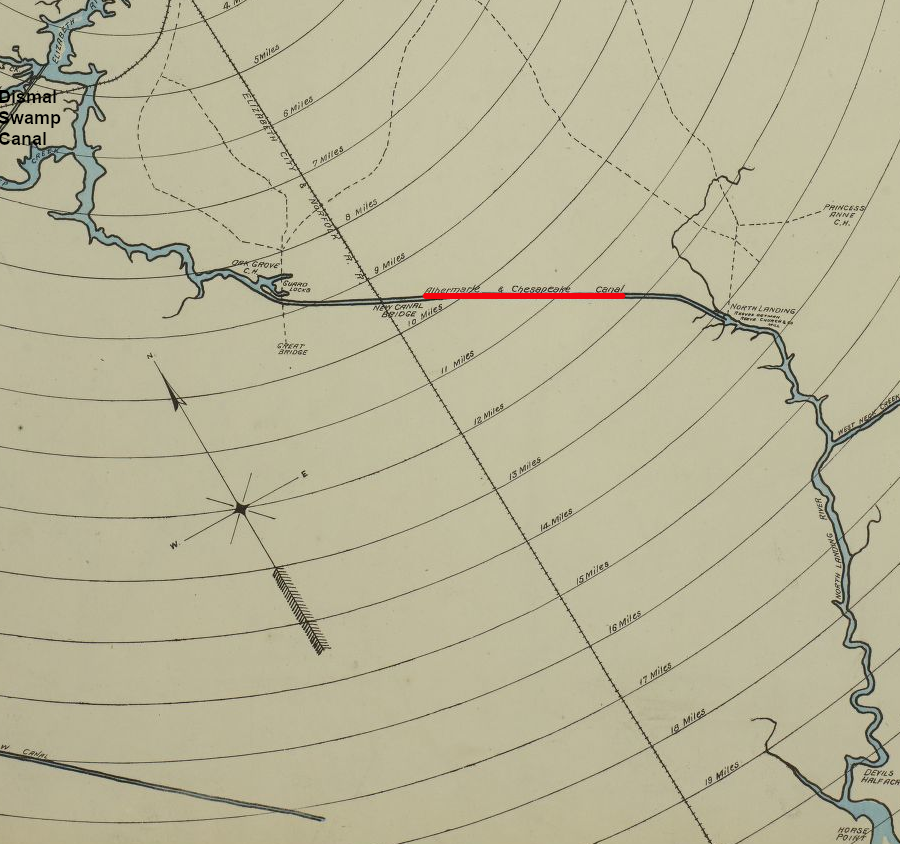

the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal competed primarily with the original Norfolk Southern Railroad and Dismal Swamp Canal

Source: University of North Carolina, Map of the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal: connecting Chesapeake Bay with Currituck, Albemarle and Pamplico sounds and their tributary streams (by A. Lindenkohl and Henry Lindenkohl, 1885)

Today the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal is Route #1 on the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway, the 1,100-mile "Marine Highway M-95" connecting Norfolk to the Florida Keys. The Dismal Swamp Canal is Route #2. Norfolk is designated as the starting point, Mile 0.0.

The US Congress provides funds for the Army Corps of Engineers to maintain the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal channel at a 12' depth by constant dredging. Primary users still include commercial boats, while the Dismal Swamp Canal is maintained to just a 6' depth and serves just recreational boats.3

Key dates in the evolution of the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal:4

1772 Virginia passes the original act authorizing the canal.

1774 Two separate feasibility and cost studies made on canal routes.

1776 Revolutionary War delays action.

1793 Construction begins on the Dismal Swamp Canal, eliminating the immediate need for the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal.

1809 Another act passed in Virginia incorporating "The Great Coastwise Canal and River Navigation Company" to cut the canal.

1812 The War of 1812 delays further action.

1812-1854 Numerous acts passed establishing companies and enabling construction. Lack of interest and funds caused further delays.

1855 Construction begins at last.

1859 Canal is completed and steamboat service begins. Plans are already underway to deepen the canal from six to eight feet.

1862 Both Confederate and Union forces sink ships in North Carolina Cut to blockade the canal.

1865-1866 Great Bridge Lock closed for three months due to leakage.

1873 New iron gates replace wooden ones at Great Bridge.

Late 1870's First suggestions made that the federal government take over the canal, make improvements and provide an inland waterway.

1913 United States buys Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal for $500,000 as part of its inland waterway plans.

1917 Lock gates removed at Great Bridge to allow passage of larger ships.

1932 New lock, built by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, opens.

1992 Great Bridge Lock Area bulkheads and fender systems upgraded.

2004 Great Bridge replaced and operations taken over by the City of Chesapeake.

2004 Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal placed on National Register of Historic Places.

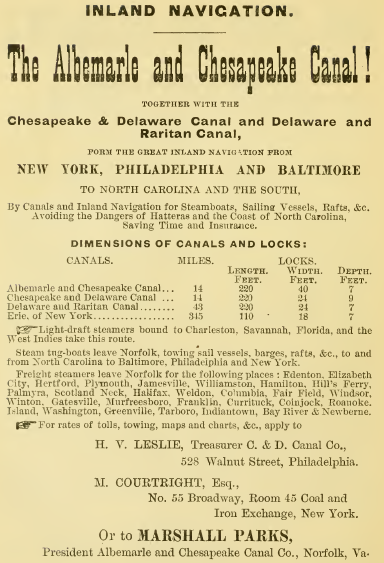

the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal advertised its suitability for inland navigation in 1881

Source: Internet Archive, A history of Old Point Comfort and Fortress Monroe, Va., from 1608 to January 1st, 1881 (1881)

railroad competition was too great for the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Norfolk 30x30 topographic map (1902)

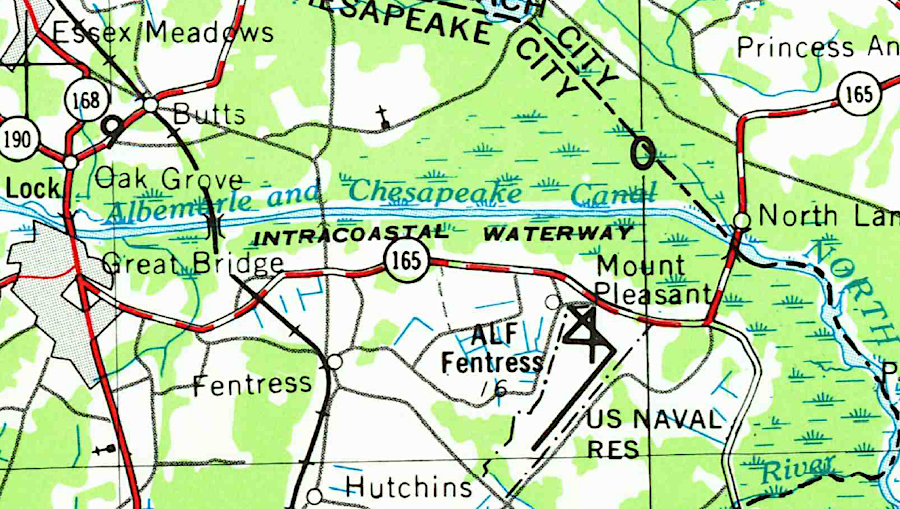

Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal, long before construction of the Chesapeake Expressway (Route 168 Bypass)

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Norfolk 1:250,000 scale topographic quadrangle (1953)

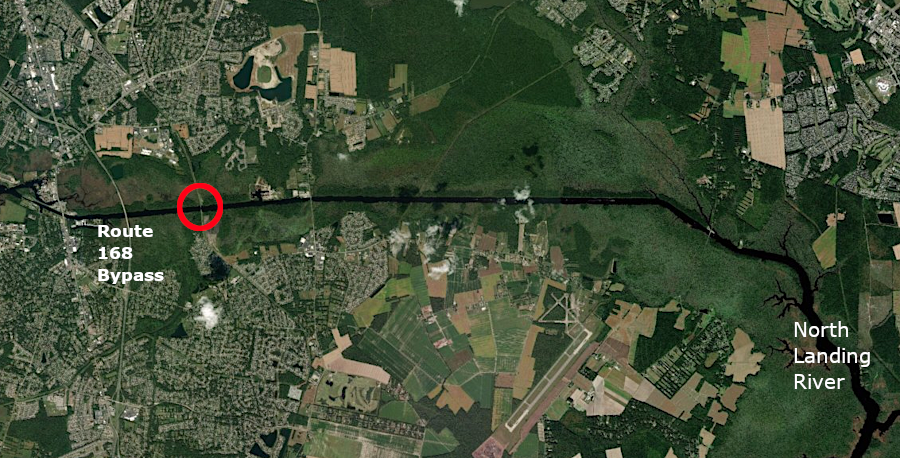

the Chesapeake and Albemarle Railroad still crosses the canal (at red circle)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

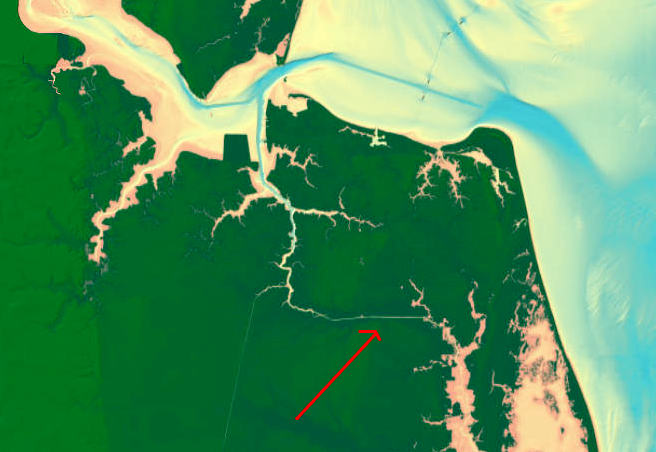

bathymetry near Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal

Source: National Ocean Service Hydrographic Survey Data, Bathymetry Map Service

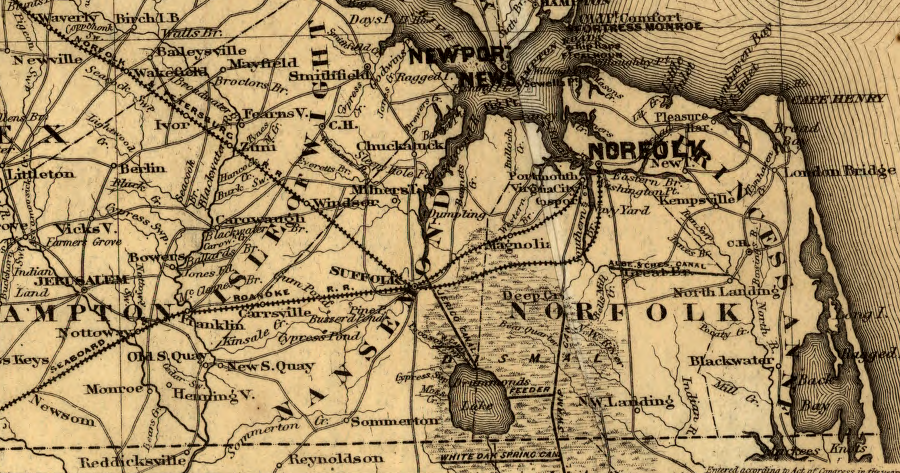

railroads linked Suffolk, Portsmouth, and Norfolk to the east, while the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal linked to North Carolina in the south

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing the Fredericksburg & Gordonsville Rail Road of Virginia (1869)

Great Bridge Lock on the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District Image Gallery

about every 25 years, the Corps of Engineers refurbishes the 72-ton gates for the Great Bridge Lock on the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District Image Gallery

a bridge has crossed the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River since before the Revolutionary War

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District Image Gallery

at Great Bridge, the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal was excavated south of the original channel of the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal competed with the Elizabeth City & Norfolk Railroad (later the "original" Norfolk Southern) and the Dismal Swamp Canal

Source: Library of Congress, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Norfolk, Independent Cities, Virginia (Sanborn Map Company, 1887)

the lock at Great Bridge is part of the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal on the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Nautical Chart 12206 (Norfolk to Albemarle Sound)

both the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal and the Dismal Swamp Canal were excavated through Norfolk County

Source: University of North Carolina, Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal: connecting Chesapeake Bay with Currituck, Albemarle, and Pamlico Sounds and their tributary streams (John Lathrop, 1858)

the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal included two excavated sections, one in Virginia and one in North Carolina

Source: New York Public Library Digital Collections, Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal (by John Lathrop, 1857)