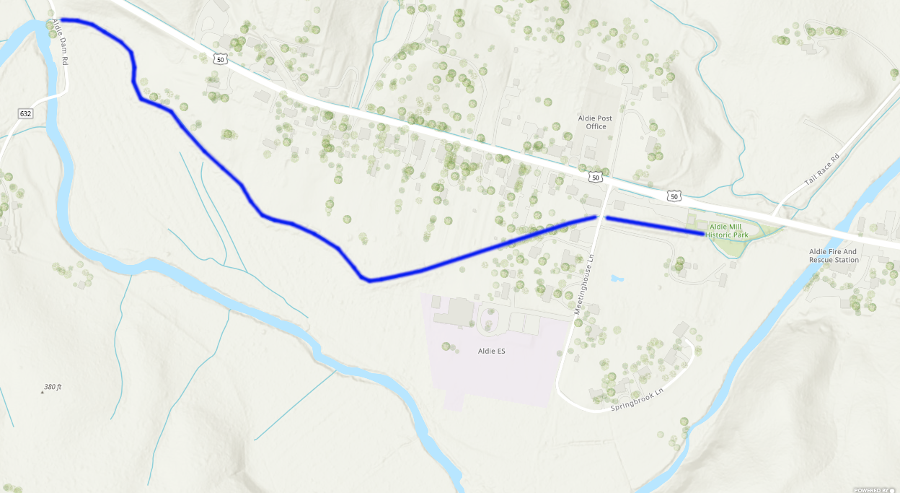

the mill race moved water that dropped down through waterwheels to power George Fenton Mercer's mill at Aldie, on the Little River

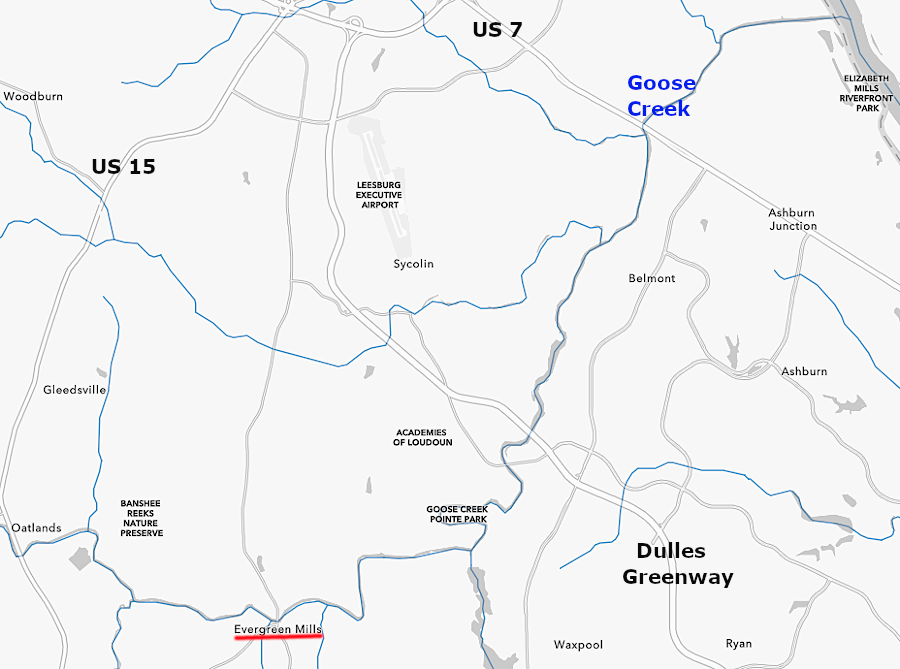

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Investors organized the Goose Creek and Little River Navigation Company in 1830, with the intention of improving the navigability of Goose Creek so mills upstream could float barrels of flour safely to the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal along the Potomac River. Upstream destinations were Duer's Mill, where the Snickersville Turnpike crossed Goose Creek, and Aldie Mills on the Little River at the end of the Little River Turnpike. The president of the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal was George Fenton Mercer, who owned mills at Aldie and was Chairman of the Committee on Roads and Canals n the US House of Representatives.

the mill race moved water that dropped down through waterwheels to power George Fenton Mercer's mill at Aldie, on the Little River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Shipping flour by boat down Goose Creek to the C&O Canal and on Georgetown would be cheaper than shipping by wagon via the Little River Turnpike to Alexandria. The reduction in transportation costs justified the investment in building expensive dams and locks on Goose Creek. The General Assembly authorized the Bureau of Public Works to purchase 40% of the company's stock in 1838.1

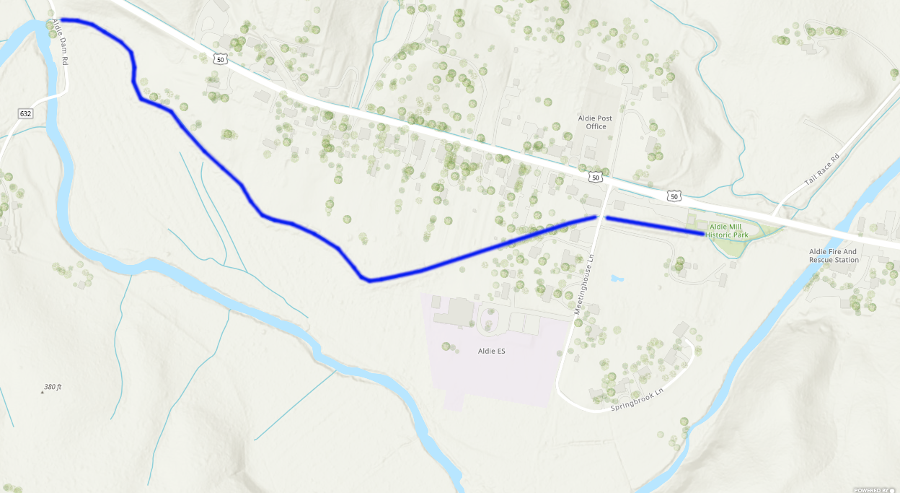

George Carter of Oatlands led the company originally; his mill at Oatlands was adjacent to Goose Creek. Eight other mill owners next to the creek also planned to ship by boat once the canal was operational. No towpath was planned. Rather than use mules to pull the boats, boatmen would push on poles.

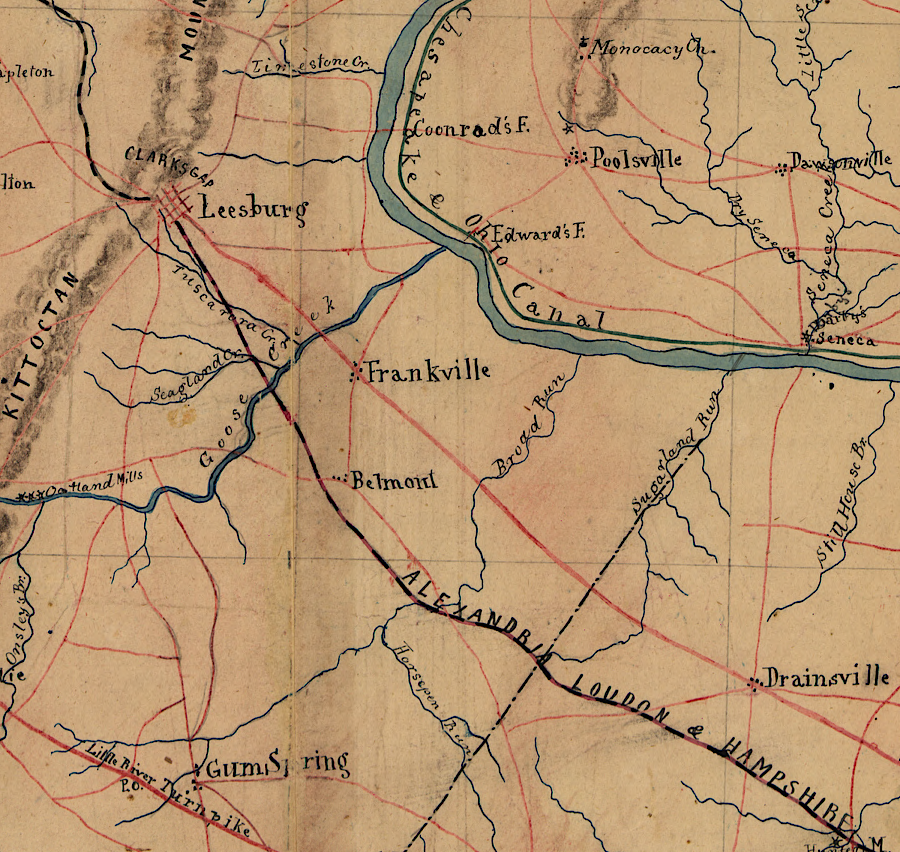

the Goose Creek Canal and the Loudoun Branch of the Manassas Gap Railroad were intended to serve George Carter's mill at Oatlands

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Loudoun County, Virginia (by Yardley Taylor, 1854)

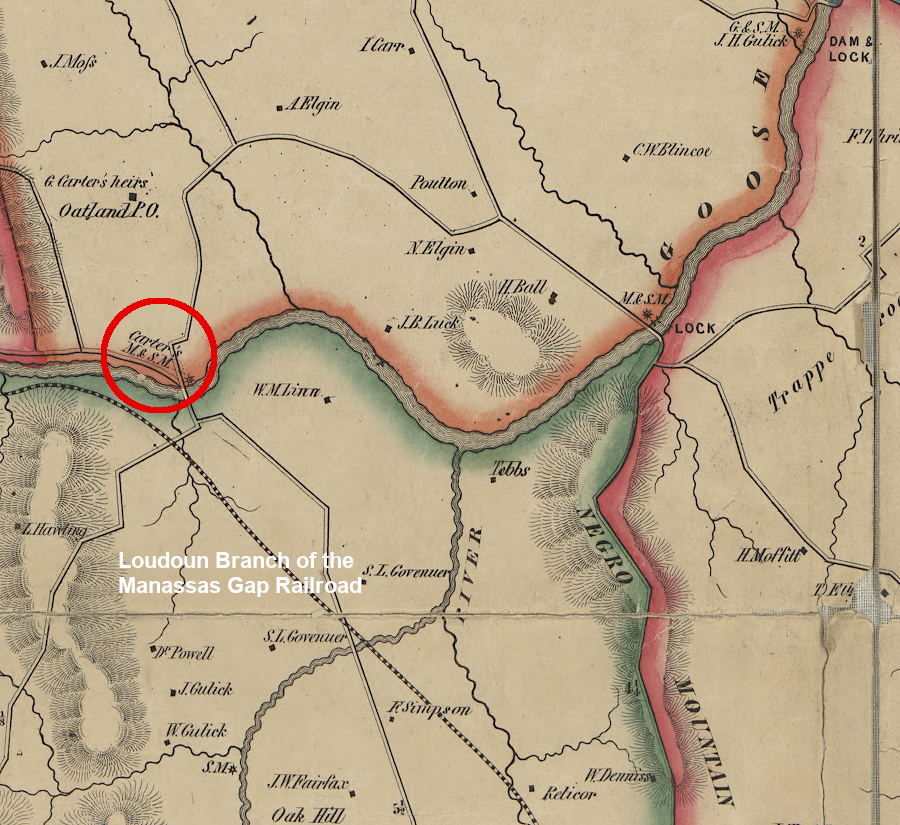

It took almost a decade to raise the 40% of private investment, then about five more years before an engineering survey was completed. The investors chose to build the more-expensive stone locks rather than wooden ones, but cut their length to just 50% of the locks on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. Shorter boats would carry fewer barrels, but costs had to be controlled.

Construction began near the mouth of Goose Creek in 1849. The first locks were a quarter-mile upstream. They made it easier for Elizabeth Mills, another half-mile upstream, to float its grain to market. Within two years, there were four locks improving navigability for seven miles of Goose Creek.

two locks were built together at Clapham's Mill, near where US 7 crosses Goose Creek

Source: Library of Congress, Historic American Engineering Record, Goose Creek & Little River Navigation, Double Lock, Mouth of Goose Creek at Potomac River

To reduce costs, plans were revised to build a system just 12 miles long. The canal would end at Balls Mill (now Evergreen Mills), rather than serve mills further upstream. Converting free-flowing Goose Creek into a series of slackwater pools required nine locks, four dams, and four segments of canal dug parallel to the creek.

Construction ended in 1854. The contractor was required to prove that a boat could float the entire 12-mile stretch in order to get paid, so he had a boat enter the mouth of the creek and hired enslaved men to pull it upstream. They dragged the empty boat across sandbars and managed to get it to the mill pond at Balls Mill, where local historian and cartographer Eugene Scheel reports it is still visible in times of low water.

only one boat ever reached Balls Mill (now Evergreen Mills), 12 miles from the mouth of Goose Creek

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The company abandoned efforts to maintain the canal system in 1857. The Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire Railroad was under construction, and it would be a less-expensive form of transportation. The canal company president noted in his final report:2

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal built a set of locks to allow boats from Goose Creek to enter the canal. Only two other "river locks" were built by the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, one at Harpers Ferrry and one near Shepherdstown opposite Boteler Mill. The Goose Creek locks were the only staircase locks on the canal, where "the lower gate of the upper lock serves as the upper gate of the lower lock."3

the towpath on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal had a bridge for mules to cross over the Goose Creek locks

Source: Wikipedia, Goose Creek River Lock inlet mule bridge over Towpath on Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

Goose Creek was listed as a State Scenic River in 1976. Today, visitors can see the one remaining lock, built at Elizabeth Mills. It is adjacent to the golf course in Elizabeth Mills Riverfront Park.4

the Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire Railroad competed successfully with the Goose Creek Canal

Source: Library of Congress, Part of map of portions of the milit'y dep'ts of Washington, Pennsylvania, Annapolis, and north eastern Virginia (1861)

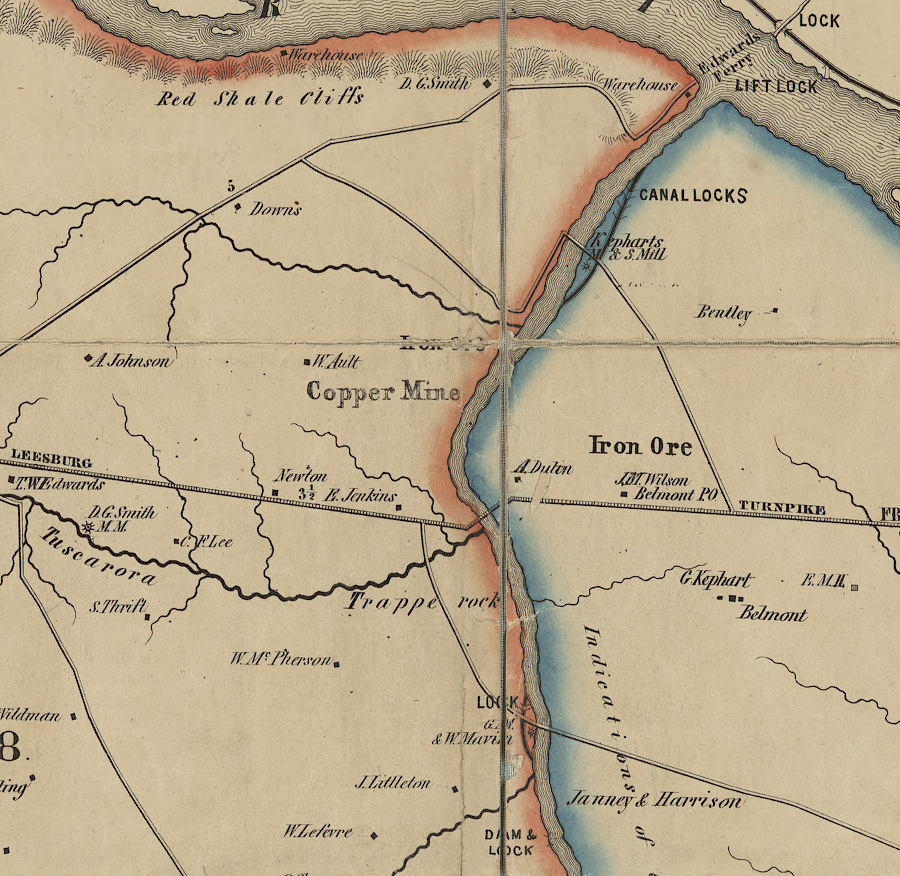

Goose Creek Canal, as envisioned in 1854

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Loudoun County, Virginia (by Yardley Taylor, 1854)