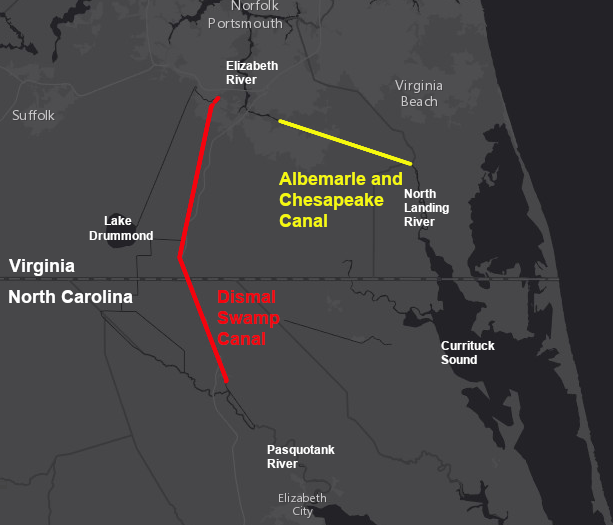

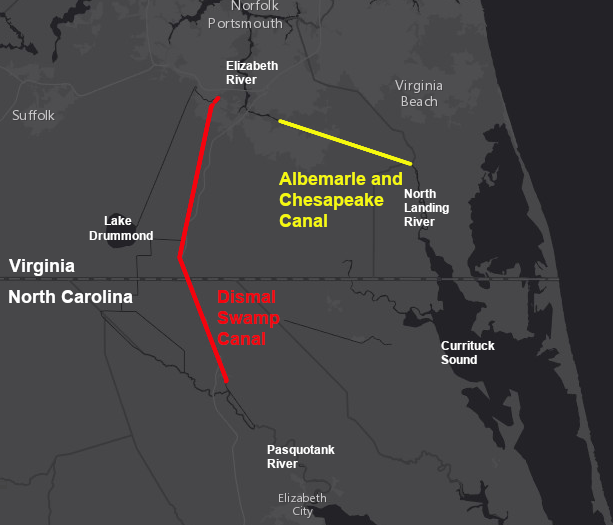

The Dismal Swamp Canal and a toll road adjacent to it was constructed between 1793-1805. Today it is the oldest operating artificial waterway in the United States. The nearby Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal was chartered earlier, but not completed until 1859. That was 54 years after the Dismal Swamp Canal opened.

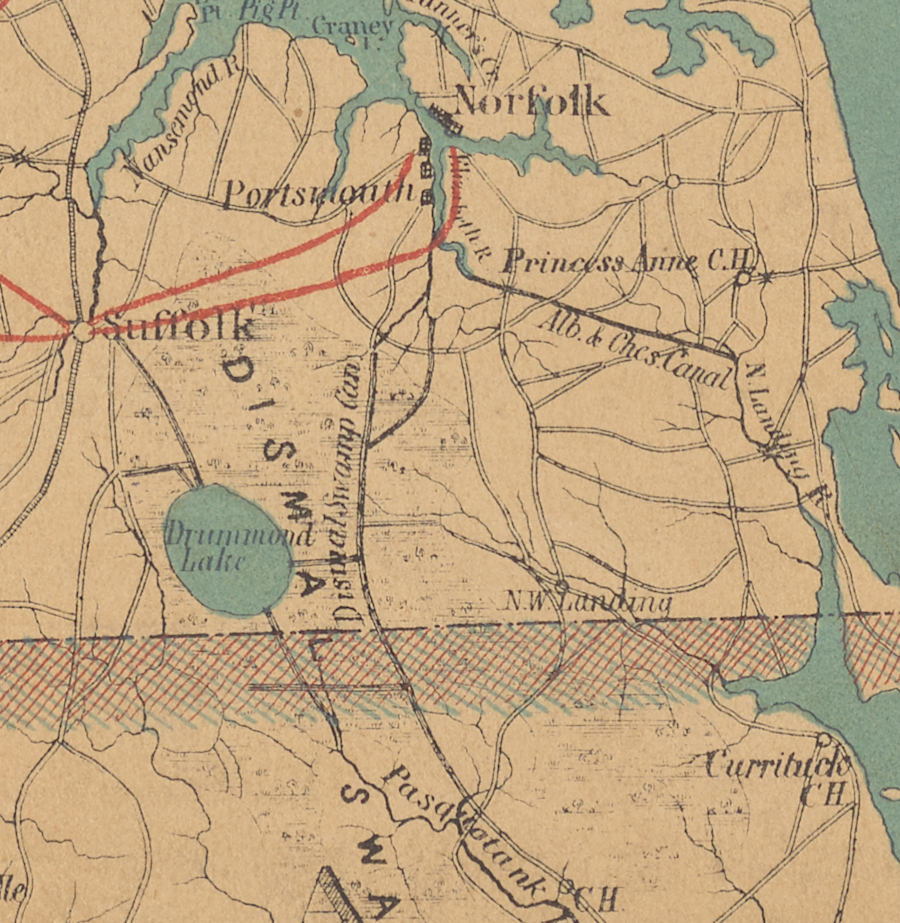

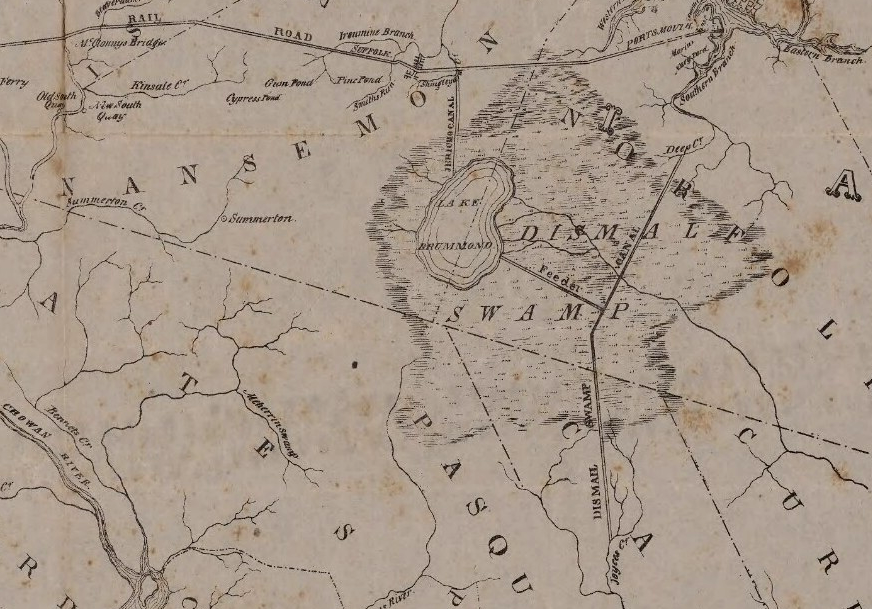

The 22-mile long Dismal Swamp Canal links the Pasquotank River at South Mills, North Carolina with Deep Creek in the City of Chesapeake, Virginia. Deep Creek flows into the South Branch of the Elizabeth River, providing boats access to the piers and wharves of the port cities of Portsmouth and Norfolk. South of South Mills, Turner's Cut was excavated in 1856 to provide a straight line alternative to the parallel Pasquotank River.

The canal enabled boats to travel from Pasquotank River, North Carolina to Deep Creek and then the South Branch of the Elizabeth River. Boats loaded with agricultural products from coastal North Carolina and later the Roanoke River watershed could reach wharves at Portsmouth and Norfolk, where cargo could be loaded onto ships going to markets in the northeastern states, Europe, and the Caribbean.

Virginia chartered the canal in 1787, and North Carolina authorized it three years later.

The original design included seven locks, 75 feet long and 9 feet wide. The entire canal was elevated above sea level, and fed by drainage through the swamp. To obtain enough water, a feeder ditch was constructed from Lake Drummond to the highest point, the "summit" of the canal. In an 1899 reconstruction, the canal was excavated eight feet deeper. That allowed for removal of all locks along the canal, except for the ones at each end which brought boats back to sea level.

North Carolina would have preferred a transportation network that carried agricultural products produced within the state to a port at the mouth of the Chowan River. Keeping the shipping activities within the boundaries of North Carolina would have stimulated jobs and tax revenues within the state.

However, the Outer Banks were a major physical barrier; the inlets between the islands were too shallow. Roanoke Inlet, the last outlet, closed between 1792-1798. No major port developed for ocean-going ships on Pamlico/Albemarle Sound, though Oregon and Hatteras inlets were created by an 1846 storm.1

The North Carolina legislature were willing to charter the canal, because it helped farmers in the Roanoke River and Albemarle Sound region get higher prices for their crops. There were more ships coming into Hampton Roads, so there were more buyers competing for products in Portsmouth and Norfolk.

Large ocean-going ships sailed regularly from their Virginia wharves to northeastern states, Europe, and the Caribbean. Being able to transport cargo to a Chesapeake Bay port made farmland in North Carolina more valuable.

In the early 1700's, colonists such as William Byrd II recognized that a canal would increase the value of farmland in southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina. Byrd led the Virginia commissioners during the 1728 survey of the Virginia-North Carolina border. He speculated in buying land that would appreciate over time, and being first to examine the territory gave him an advantage.

Byrd was not interested in the Great Dismal Swamp, even though he could get a land grant at the lowest possible cost, because the region lacked access to markets:2

- It would be a valuable tract of land in any country but North Carolina, where, for want of navigation and commerce, the best estate affords little more than a coarse subsistence...

A canal next to the Dismal Swamp was not the only way to connect the Roanoke/Chowan River to the Elizabeth River. There were two routes for building a canal connecting North Carolina to the Chesapeake Bay port.

The shortest route for boats to carry lumber, staves, shingles, tar, turpentine, tobacco, and other agricultural products from northeastern North Carolina to a Chesapeake Bay port was to go up the North Landing River to its headwaters, seven miles east of the headwaters of the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River. Cargo carried by wagon for the seven miles could be reloaded onto another boat at the headwaters of the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River, then floated north to the Chesapeake Bay ports of Portsmouth and Norfolk. However, the first canal linking the Albemarle Sound to the Chesapeake Bay did not close that seven-mile gap.

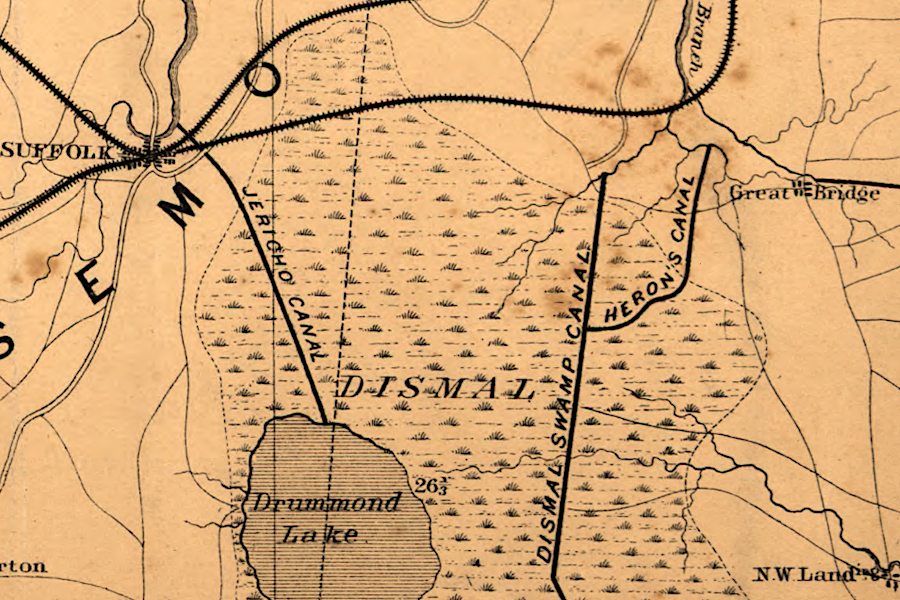

The first canal was dug eight miles west of the North Landing River, on the eastern edge of the Dismal Swamp. The Dismal Swamp Canal connected the Pasquotank River in North Carolina to Deep Creek, a tributary of the South Branch of the Elizabeth River.

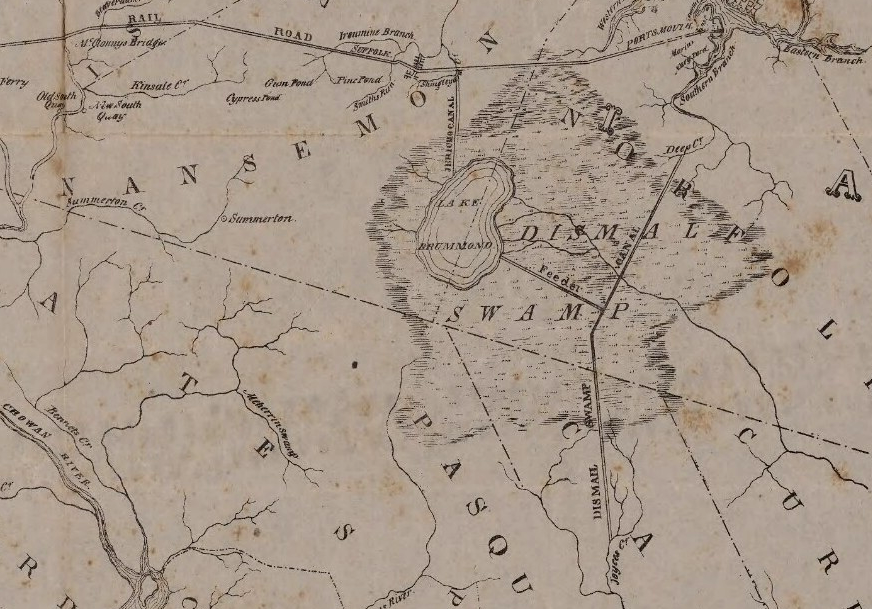

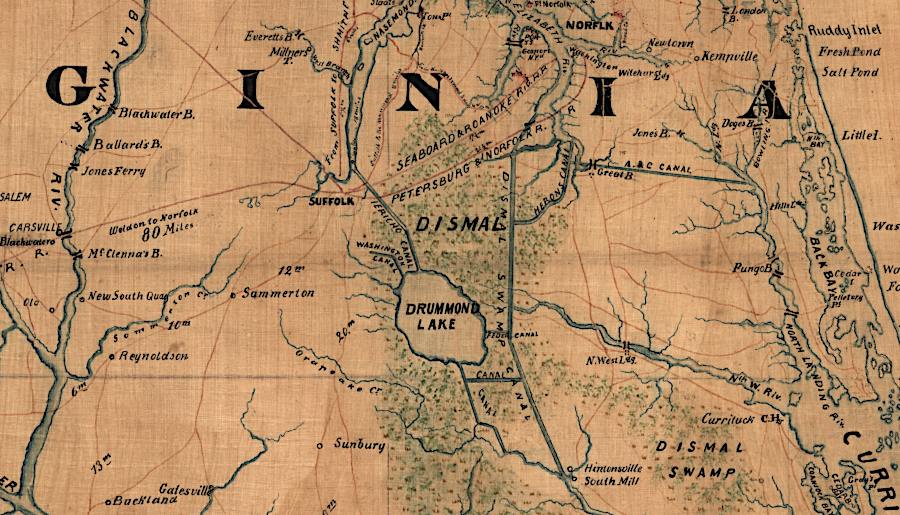

the Dismal Swamp Canal enabled boats traveling down the Roanoke (Chowan) River to Albemarle Sound to access a Chesapeake Bay port on the Elizabeth River

Source: University of Virginia, Plan of the Portsmouth and Roanoke Rail Road

A dozen land speculators, including George Washington, had organized the Dismal Swamp Company in 1763. Its primary aim was to drain the wetlands and convert them to farmland, growing crops such as wheat which could be exported via the Chesapeake Bay. The first steps including using enslaved people to dig ditches and cut the cypress trees to clear the land.

As the land was cleared, the company's profits would come from shingles and other timber-related products. The drained and cleared farmland could be used to grow grains and hemp (Cannabis sativa), which produced a fiber used for manufacturing rope needed by sailing ships, seine nets, and clothing.

Economic disruption before, during, and after the American Revolution blocked development. In 1793, Patrick Henry led the effort to start digging a Dismal Swamp Canal, and a separate company was organized for that project. At the time, George Washington was busy in Philadelphia with his responsibilities as President of the United States. Washington sold his shares in the Dismal Swamp Company two years after canal digging began.

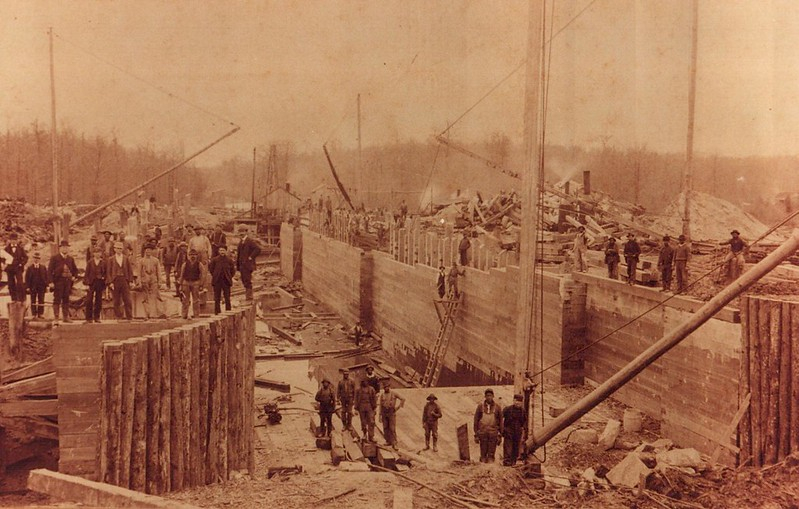

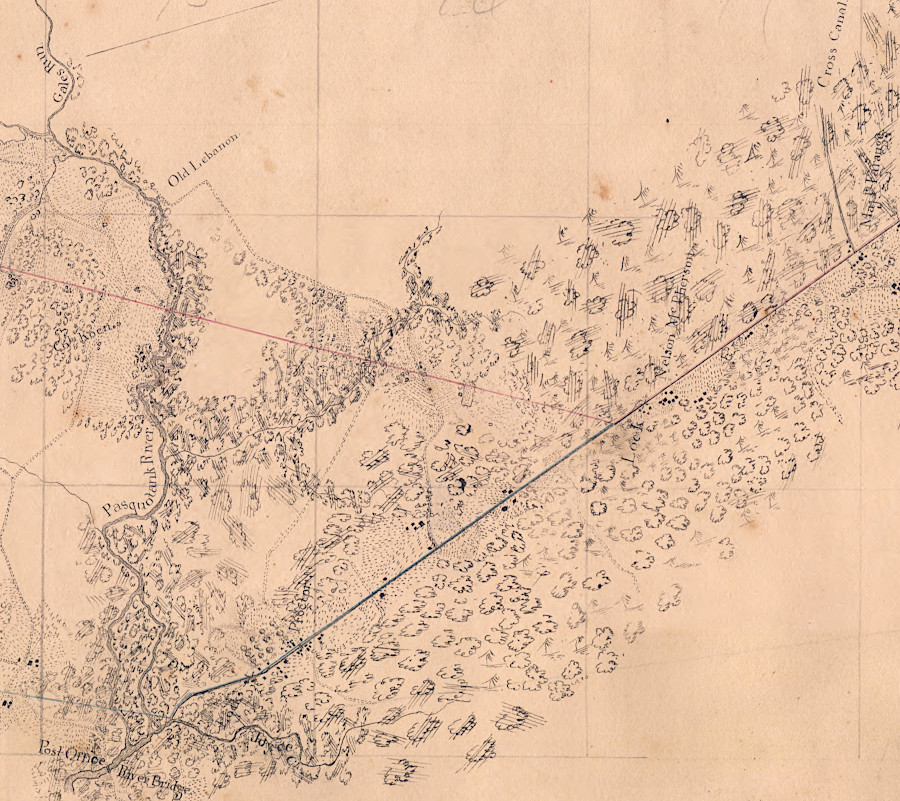

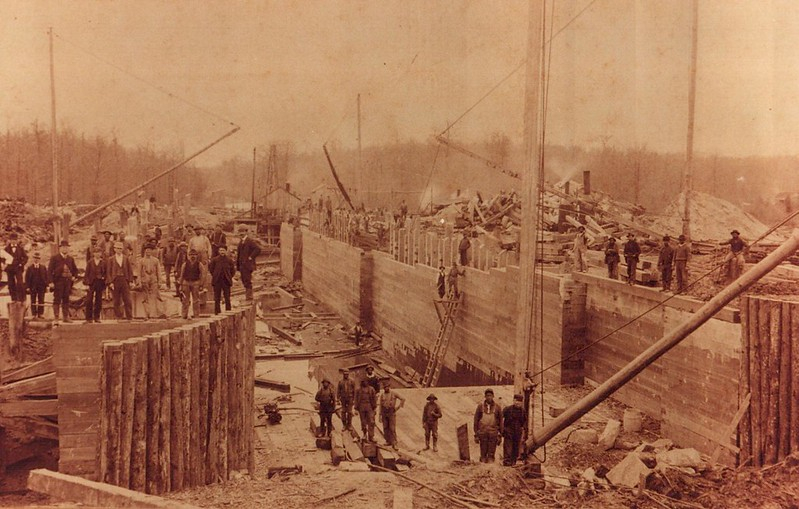

Construction started at Deep Creek on the northern end, and at Joyce Creek on the southern end. The enslaved men who dug the canal by hand averaged just 10 feet per day.

The working conditions were brutal, with laborers standing in water, mud, and muck every day. Cutting roots underwater and prying them out with hand tools must have been exhausting.

Even today, people who travel into the swamp in the summer may find clouds of mosquitoes thick enough to obscure the presence of another person just a dozen feet away. A four-person archeology team seeking access to once-occupied islands within Great Dismal Swamp struggled in 2016 for eight hours to cut a trail through the thick brush. The team abandoned their effort after advancing only 200 feet.3

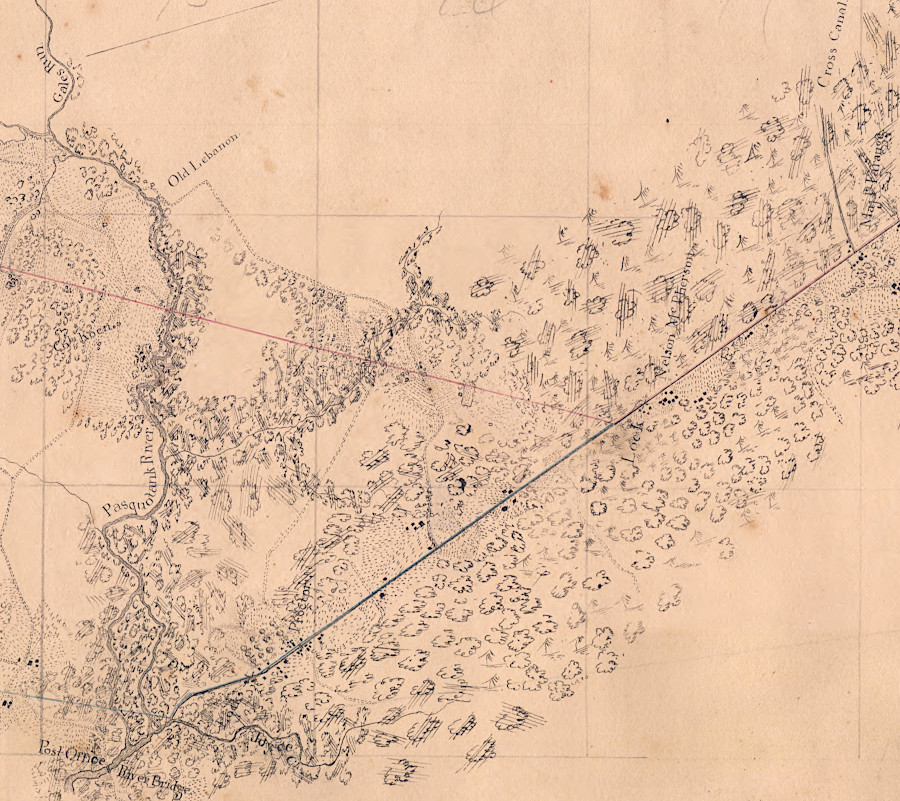

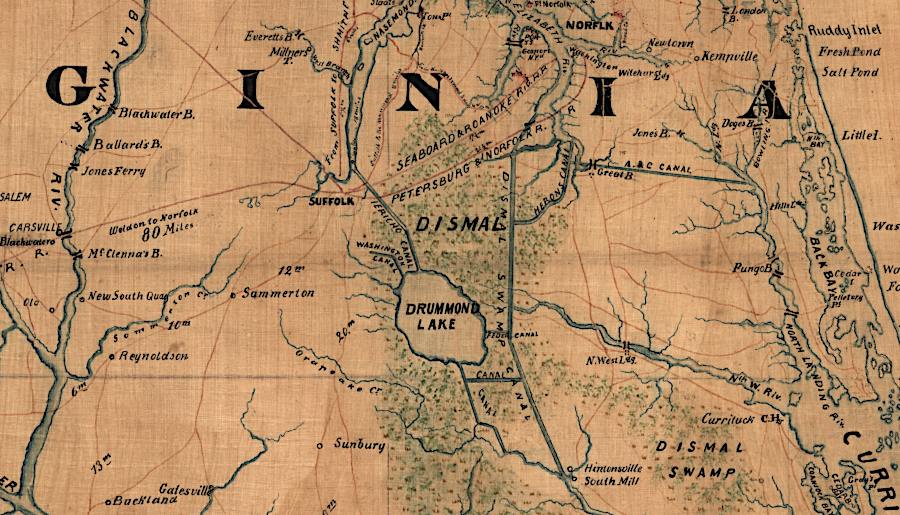

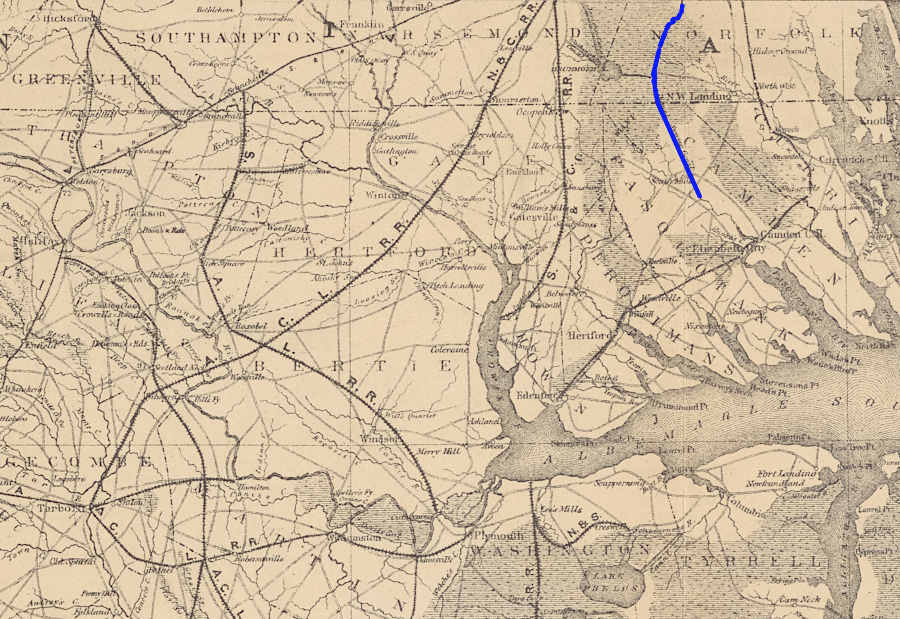

the Dismal Swamp Canal was cut as a straight line through wetlands north of the Pasquotank River

Source: University of North Carolina, Untitled map showing area from Edenton northeast to the Dismal Swamp Canal (by Walter Gwynn, c.1830's)

The Dismal Swamp Canal was the Commonwealth of Virginia's first large-scale public works project. The lack of experience showed. Construction paused in 1796, while a toll road was built to connect the two ends of the unfinished canal. A road ultimately constructed parallel to the canal has evolved into modern US 17.

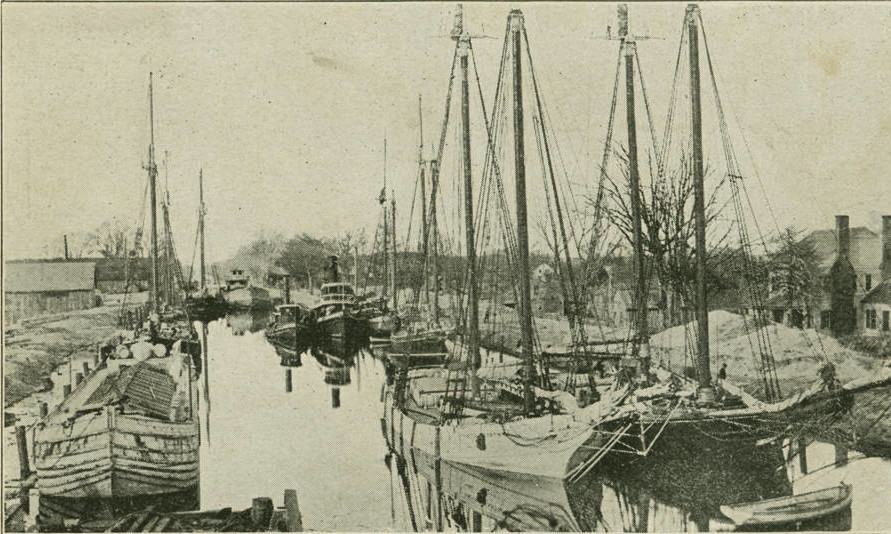

The initial version of the Dismal Swamp Canal was finally completed in 1805. Engineers miscalculated the elevations at each end, water levels were too low, and the canal was suitable only for very shallow barges and flat-bottomed "lighter boats" (gondolas). Initially, the only traffic consisted of log rafts and flat-bottomed boats loaded with shingles which had been produced within the swamp adjacent to the canal. Local timber, including barrel staves manufactured from local cypress trees, were the primary freight.

The three-mile long Feeder Ditch adding water from Lake Drummond was completed in 1812. Agricultural products from the Roanoke River started moving north to Norfolk only in 1814, when a 20-ton boat from the Roanoke River could move up the Pasquotank River and then use the canal to get to a Chesapeake Bay port. Not until 1823 was a fully-loaded, 35-ton vessel able to travel the entire canal. Afterwards, the North Carolina town of Edenton lost a significant amount of business, and its economy shifted from trading to fishing.

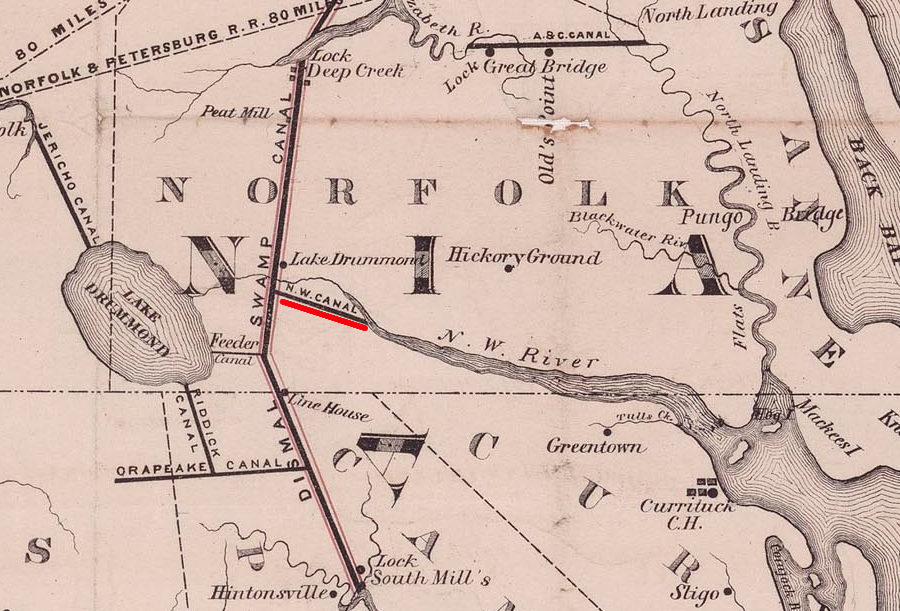

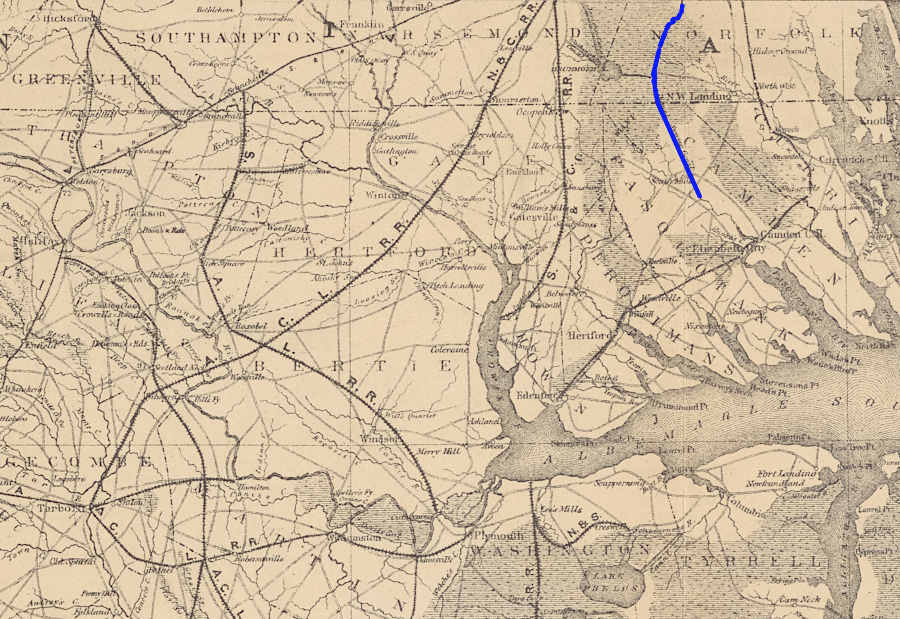

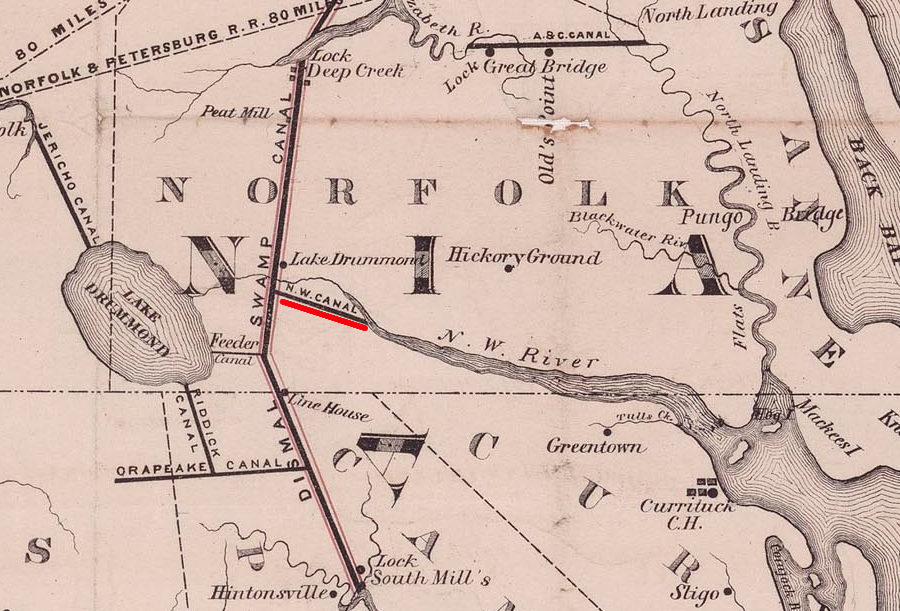

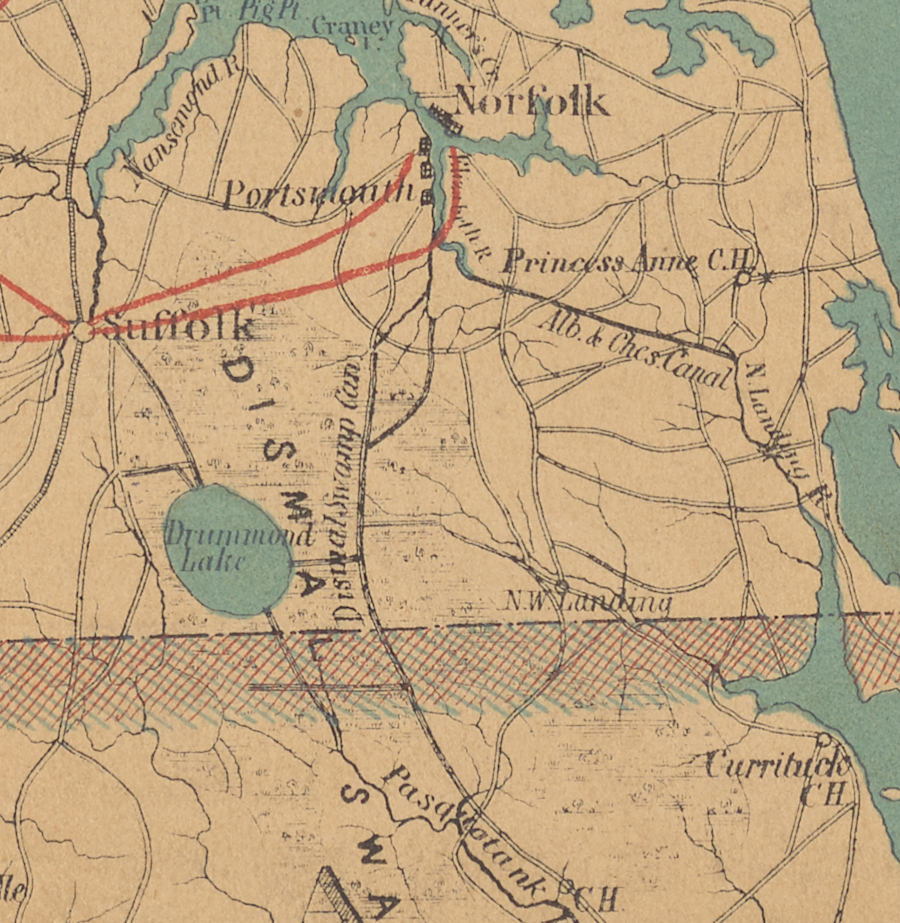

Even after construction of the Feeder Ditch connection to Lake Drummond, managing water levels remained a challenge. Another ditch from the canal to the Northwest River was cut in 1820 to drain excess water from the canal. The ditch was expanded into the Northwest River Canal in 1832, so flatboats could carry cargo between the Dismal Swamp Canal and the Northwest River.

the 1820 ditch to drain excess water from the canal to the Northwest River was improved to allow boat traffic in 1832

Source: NCpedia, Dismal Swamp Canal connecting the Chesapeake Bay with Currituck, Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds and their tributary streams (by D.S. Walton, 1867)

Walter Herron built a three-mile ditch to the Dismal Swamp Canal in the 1820's to float timber products from swampland on the eastern side to market in Norfolk. The ditch was later extended to the South Branch of the Elizabeth River. The "Herring Canal" became a shortcut to the headwaters of the South Branch, where the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal ended up connecting to the North Landing River.

Walter Herron's ditch became a shortcut to the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal

Source: Library of Congress, E. & G. W. Blunt's corrected map of the seat of war near Richmond, July 10th, 1862

At the North Carolina-Virginia border, the "Halfway House" provided food, drink, and shelter to travelers. It became a destination too. Virginians came to take advantage of looser North Carolina marriage laws. Others chose to fight duels there, or to evade capture by stepping across the state line if a sheriff arrived. A floating theatre travelled through the canal, providing the inspiration for the later Broadway musical "Showboat."

In 1826 and again in 1829, the Federal government provided financial support to deepen the channel and replace the wooden locks with cement. Norfolk merchants had invested in a project to increase traffic, the Roanoke Navigation Company. It improved the shipping channel upstream of the Fall Line and built the Roanoke River Canal to bypass the rapids at Weldon, North Carolina.

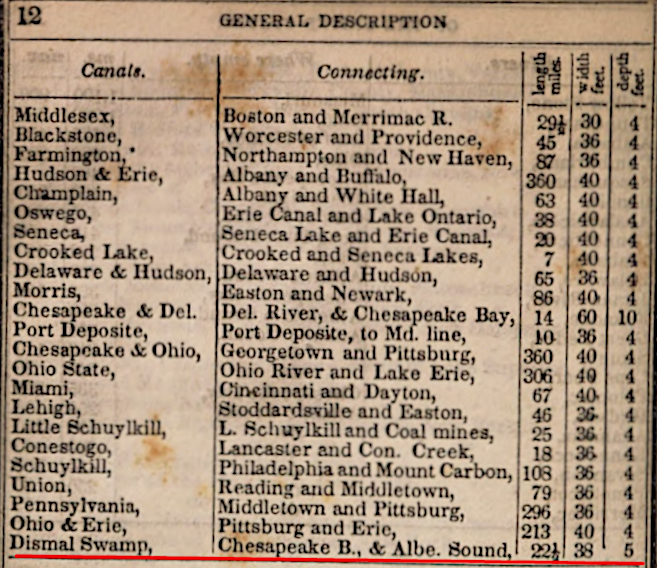

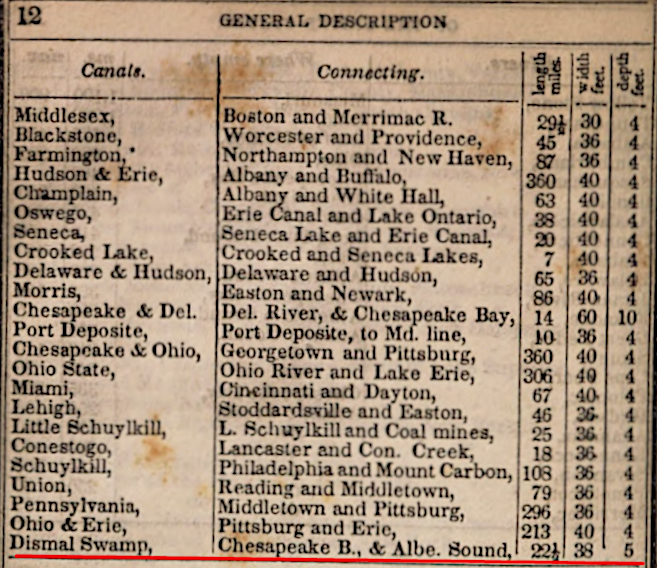

in 1838, a traveler's guide described the Dismal Swamp Canal as 5' deep

Source: Hathi Trust, Phelps & Ensign's travellers' guide through the United States (1838)

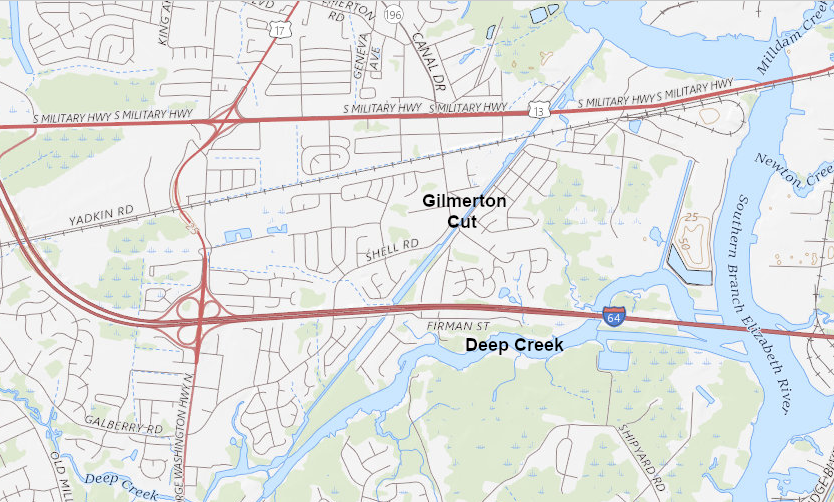

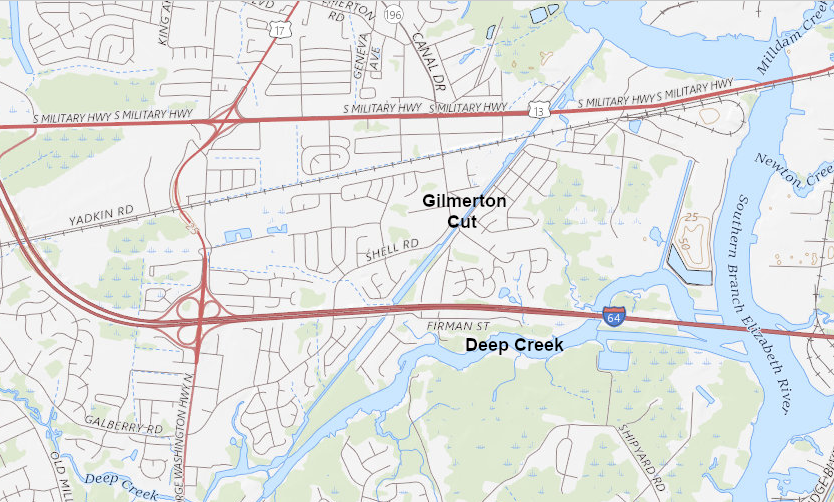

In 1843, a 2.5-mile canal was added at the north end to eliminate the stretch through Deep Creek. The Gilmerton Cut provided a straight-line connection to the Elizabeth River, shortening the distance and speeding travel to Portsmouth and Norfolk.

One lock was built at the northern tip of the cut, which a rock barrier across Deep Creek diverted water into the cut. In 1899, the main channel was re-routed back to Deep Creek and the Gilmerton Cut was abandoned.4

the Gilmerton Cut was opened in 1843

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

a lock was built at the north end of the Gilmerton Cut

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the lock built at the north end of the Gilmerton Cut is still present

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Petersburg Railroad reached the Roanoke River near Weldon in 1833. It diverted trade north to Petersburg, a rival port competing with Portsmouth and Norfolk.

Completion in 1834 of the Roanoke River Canal between Gaston and Weldon, North Carolina countered the Petersburg Railroad. The canal bypassed the rapids, making it easier for batteaux to stay on the water. Cargo that stayed in boats could be towed by steamships to the Pasquotank River, then go to an Elizabeth River port via the Dismal Swamp Canal.

The next steps in the shipping competition came in 1837.

The Portsmouth and Roanoke Railroad built track from Portsmouth to the Roanoke River in 1837. It expanded the Weldon Toll Bridge over the Roanoke River to reach the Roanoke River Canal on the south bank at Weldon. The new railroad provided a faster connection to Portsmouth than sending cargo by boat via the Dismal Swamp Canal.

The Petersburg Railroad was denied permission to use the same bridge, or to build a competing bridge across the river. In response, the railroad built an 18-mile branch line from Hicksford (now Emporia) to a location on the Roanoke River upstream of the Fall Line rapids. The new Greensville and Roanoke Railroad intercepted batteaux traffic before it reached the Roanoke River Canal and the Portsmouth and Roanoke Railroad.

The Wilmington and Raleigh Railroad reached Weldon in 1840. It diverted traffic to Wilmington, North Carolina's main port city, further reducing the amount of cargo that might get to the Dismal Swamp Canal.

Competition between the railroads was intense. At one point, the Petersburg Railroad destroyed the track of the Portsmouth and Roanoke Railroad, blocking transportation to the rival port of Portsmouth. Once the dispute was settled, the Portsmouth and Roanoke Railroad was renamed the Seaboard and Roanoke Railroad and it continued as an alternative to the Dismal Swamp Canal.

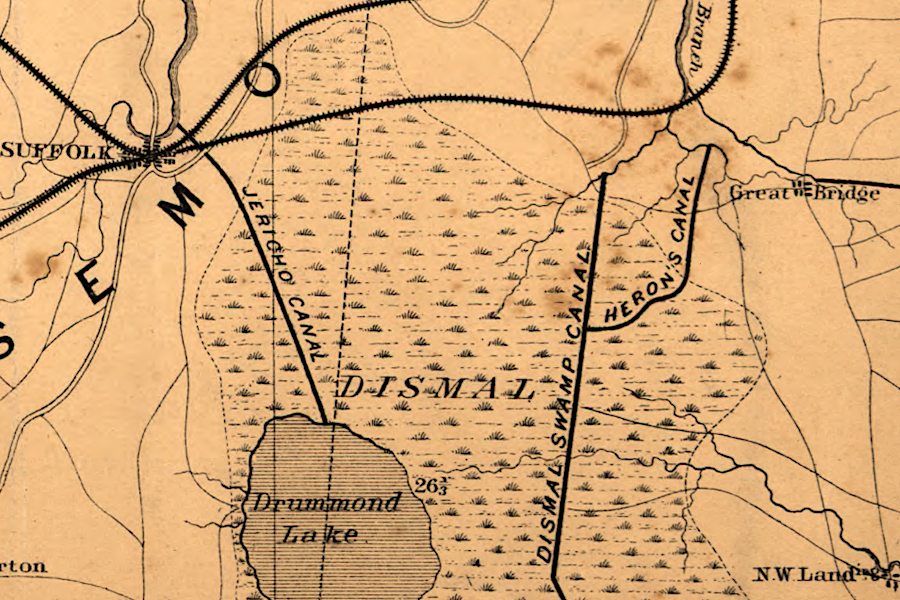

in 1860, the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal and the Seaboard and Roanoke Railroad competed with the Dismal Swamp Canal to bring freight to the Elizabeth River ports

Source: Library of Congress, S.E. portion of Virginia and N.E. portion of N'th Carolina (by Thomas Jefferson Cram, 186_)

The rival Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal opened in 1859. It was deeper, and competed for traffic from the coastal area east of the Dismal Swamp Canal as well as for boats that floated down the Roanoke River.

the Dismal Swamp Canal was completed in 1805, 54 years before the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

At the start of the Civil War, Confederate forces in North Carolina and Virginia controlled the Dismal Swamp Canal, the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal, the Seaboard and Roanoke Railroad, and the Norfolk and Portsmouth Railroad. The Union Navy blockaded the ports of the Confederacy to interrupt delivery of war material from Europe. Wilmington, North Carolina managed to stay in business despite the blockade, so Union forces planned to block the canals.

When the Union Navy captured Elizabeth City, North Carolina, two Confederate boats in the "mosquito fleet" fled north up the Pasquotank River. The captains planned to escape via the canal to Norfolk. The C.S.S. Beaufort succeeded, but the C.S.S. Appomattox was two inches too wide to fit into the lock at South Mills.

On April 19, 1862 , Union forces attempted to capture South Mills and destroy the lock. The expedition failed, but the Federal forces captured Norfolk a month later after the USS Monitor fought the CSS Virginia. Confederates never regained control of the canal. They did benefit from extensive smuggling via the canal during the rest of the war.5

at the start of the Civil War, the Dismal Swamp Canal was competing primarily with two railroads and one canal

Source: New York Public Library Digital Connections, Map of eastern Virginia (by Alexander D. Bache, 1862)

After the Civil War, tolls from freight traffic were low and sediment reduced the canal's depth to just three feet. Railroad competition increased when the Elizabeth City & Norfolk Railroad (later the "original" Norfolk Southern) was completed to Edenton in 1881. The Suffolk & Carolina Railway reached the Chowan River by 1887, and the Norfolk & Carolina Railroad started operations to Tarboro in 1890.

in 1892, the Dismal Swamp Canal was competing with multiple railroads that linked northeastern North Carolina to Suffolk, Portsmouth, and Norfolk

Source: New York Public Library Digital Connections, Map of North Carolina showing the distribution of iron ores (Washington C. Kerr, 1892)

The Lake Drummond Canal & Water Company took control of the Dismal Swamp Canal in 1892. After substantial repairs in 1896-1899, the Dismal Swamp Canal carried more traffic than the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal.

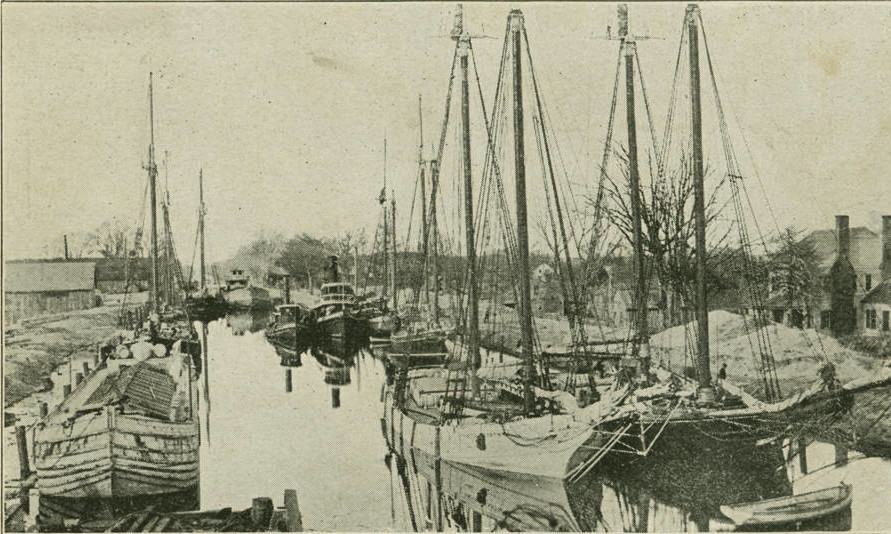

assembling boats to be towed along the Dismal Swamp Canal in 1906

Source: University of North Carolina, Dismal Swamp Canal (1906 postcard)

logs cut in the Dismal Swamp were shipped on the canal for processing at mills

Source: Library of Congress, Unloading logs on the canal, Dismal Swamp (by Alfred S. Campbell, 1896)

The Federal government acquired the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal in 1913, making it part of the Intracoastal Waterway. When the government eliminated the tolls previously charged by the private corporation, traffic shifted from the Dismal Swamp to the free alternative. That led to Federal purchase of the Dismal Swamp Canal in 1929.6

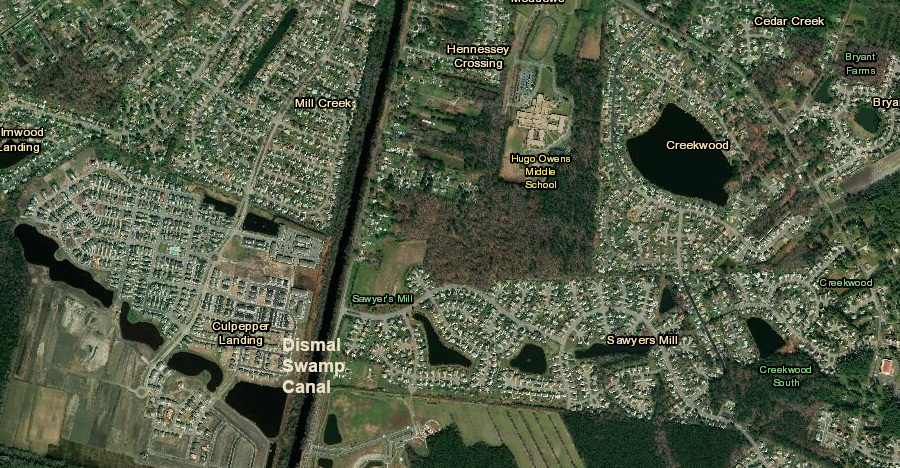

The Federal government owns the canal ditch and a narrow strip of land on either side, except for spots where dredged materials are disposed.

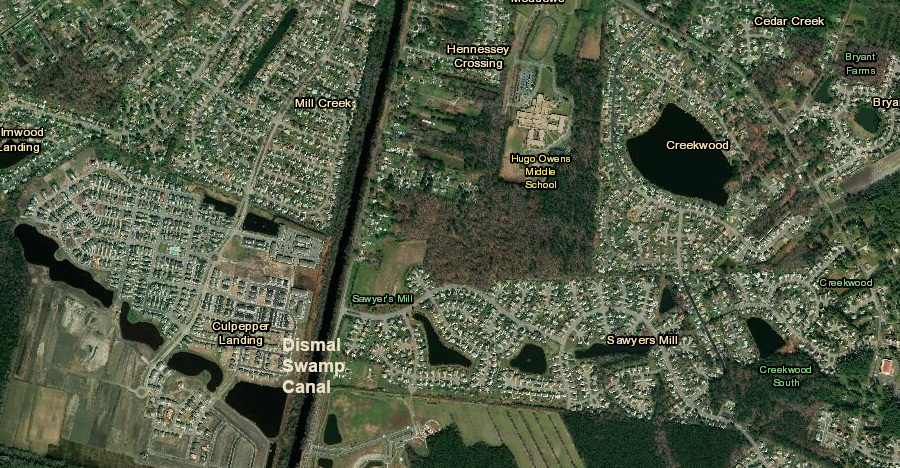

the Federal government acquired the Dismal Swamp Canal, with just a narrow strip of adjacent land, in 1929

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The US Army Corps of Engineers dredges the canal to maintain a 6' depth, though the US Congress has authorized a 9' deep channel. The canal is 100' wide, with a navigation channel maintained at 50' wide. The Feeder Ditch is four feet deep and 40' wide.

At Deep Creek on the north end and at South Mills on the south end there are locks 300' long, 52' wide, and 12' deep. Spillways there are opened and closed as needed to maintain the water level in the canal, preventing excessively-high water that might flood over the canal's banks. A spillway near Lake Drummond controls flow into the Feeder Ditch. That ditch, dug in 1812, serves as an outlet when lake levels rise too high, and directs supplemental water from Lake Drummond to the canal during periods of low rainfall. A rail tramway allows boaters to cross the spillway and go back and forth from Lake Drummond and the Feeder Ditch.

The canal has been the eastern boundary of the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge since it was established in 1974, and is also the eastern boundary of a state park in North Carolina. Creating the wildlife refuge changed the priorities for managing water levels in Lake Drummond. During droughts, conservation of natural resources within the refuge now supersedes the need of the Corps of Engineers for supplemental water from the lake for navigation in the canal.

The Federal government built the current two locks in 1940-41; the original canal had nine locks. The government also built replacements for the two wooden bridges across the locks, one at either end, and spillways to release excess water from the canal. New steel bascule bridges which could be opened to allow boats to pass were constructed in 1933-34. Two-lane US 17 parallels the canal on its east side, and crosses the canal at the two ends over bascule bridges.7

the Dismal Creek lock

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 020811-A-5177B-011

1941 was the last year the James Adams Floating Theatre, the "show boat," traveled through the Dismal Swamp Canal. It visited he canal twice annually from its maiden voyage in 1914, to offer theater to North Carolina communities in Pamlico/Albemarle Sound and then reach Maryland/Virginia communities along the Chesapeake Bay. The barge required only 14 inches of water to float, so tugs had no problem pulling it through the 6-foot deep canal.

The boat stopped at South Mills on the southern end and Deep Creek on the northern end, offering a different show daily. The 34-foot wide, 128-foot long boat had room for 500 people in the auditorium and 350 more in the balcony. The number of days spent at each location depended upon audience interest. When ticket sales declined, the boat would move to another destination where posters would advertise its arrival and shows.8

The renovated canal was a useful freight corridor in World War II, when German submarines threatened shipping along the Atlantic Ocean coast. That was the only war in which it provided a strategic transportation service. The canal was not deep enough to carry much trade in the War of 1812, and was blocked by Federal forces during the Civil War.

spillways on both ends of the Dismal Swamp Canal release excess water and prevent flooding that might erode sides (banks) of the canal

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (July 27, 2017)

water from Lake Drummond is released as needed in dry periods to maintain the 6' depth of the Dismal Swamp Canal

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (July 27, 2017)

Today the Dismal Swamp Canal is a route for pleasure boaters rather than freight. The canal has been designated Route #2 on the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway, Marine Highway M-95. The Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal is Route #1, and is dredged to 12' deep compared to the 6' depth of the Dismal Swamp Canal.

the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal is Route #1 and the Dismal Swamp Canal is Route #2 on the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (July 27, 2017)

Lake Drummond flooded during Hurricane Mathew in 2016 and carried sand down the Feeder Ditch into the canal, reducing the depth in places to just one foot. The Corps closed the canal for over a year to dredge the shoals and remove over 350 trees that fell across the waterway.9

a crane barge removed downed trees in the feeder ditch after Hurricane Mathew in 2016

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 161027-OI229-A-009 and Dismal Swamp Canal continues 85-year revival

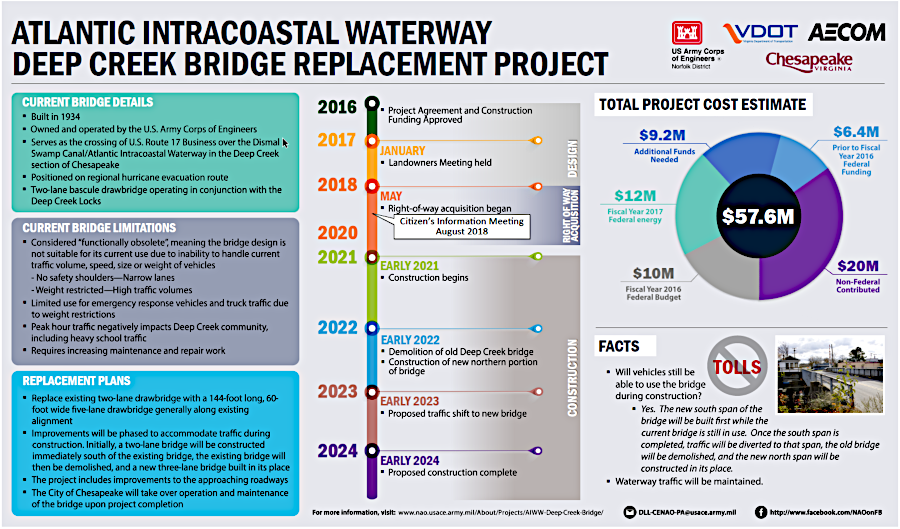

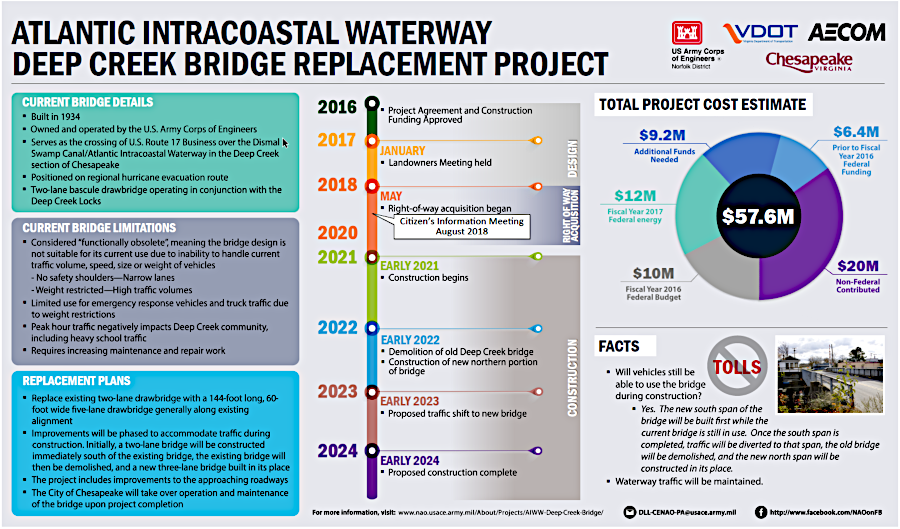

The 1934 bridge carrying US 17 over the canal at Deep Creek became a major traffic bottleneck, as the population in the region grew. The Federal government owned the structure, not the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) or the City of Chesapeake. The bottleneck would be a significant problem if the region had to be evacuated in a hurricane.

The US Congress funded most of the nearly $60 million required to replace the two-lane structure with a five-lane drawbridge and to improve the approaches. The city agreed to operate and maintain the bridge after construction was completed.10

Routine maintenance also requires occasional closure of the canal. After the seasonal migration of boats to the south in 2019, the Dismal Swamp Canal was closed so the gates at the South Mills lock could be replaced on a standard 15-20 cycle. The Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal remained open to boat traffic, so the 90-day closure did not interrupt traffic.

The US Army Corps of Engineers announced:11

- There are no spare gates for locks on the Dismal Swamp Canal. This requires us to shut the canal - then remove, refurbish and replace the gates during the slower months. There are no boats in the canal now. We notified the Coast Guard, and we will not let any vessels in at South Mills Lock or Deep Creek Lock until this refurbishment is complete.

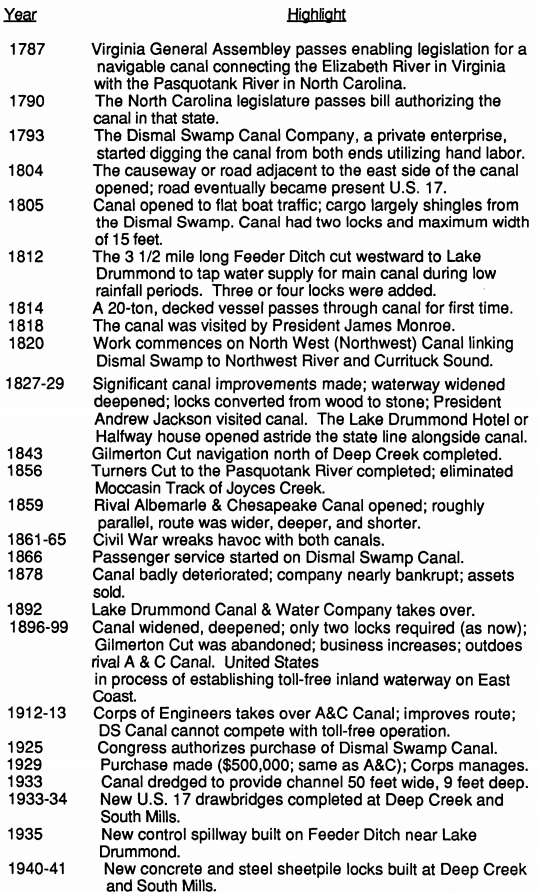

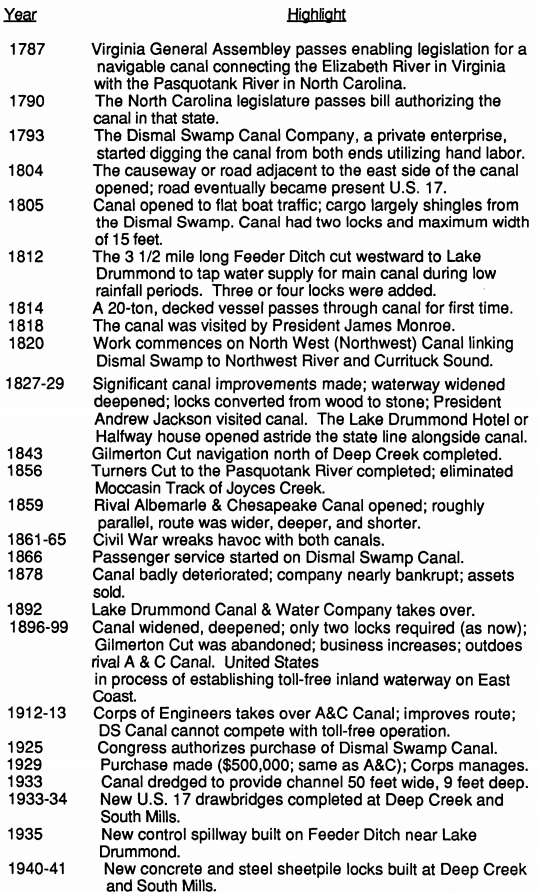

Key dates in the evolution of the Dismal Swamp Canal:12

1728 Colonel William Byrd II first proposes a canal.

1787 Virginia authorizes canal construction.

1790 North Carolina authorizes canal construction.

1793 The Dismal Swamp Canal Company begins digging.

1804 The causeway road opens, eventually becoming U.S. 17.

1805 The full length of the canal opens.

1812 The Feeder Ditch supplying water is cut. Number of locks is expanded from two to five or six.

1814 A 20-ton decked vessel passes for the first time.

1818 President James Monroe visits.

1820 Canal built connecting Dismal Swamp to Northwest River and Currituck Sound. Some remnants still exist.

1827-1829 Canal widened and deepened. Locks converted from wood to stone. President Andrew Jackson visits. Lake Drummond Hotel, the "Halfway House," opens.

1843 Gilmerton Canal, no longer in use, is made north of Deep Creek.

1856 Turner's Cut completed, eliminating twists of Joyce's Creek.

1859 Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal opens.

1861-1865 Civil War takes toll on both canals. Ships sunk to block Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal.

1866 Passenger service starts on Dismal Swamp Canal.

1878 Company is nearly bankrupt, canal deteriorates, and assets are sold.

1892 Lake Drummond Canal & Water Company takes over.

1896-1899 Major improvements made, locks cut to two. The United States Government is in the process of establishing a toll-free inland waterway along the East Coast.

1913 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers takes over the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal.

1925 Congress authorizes purchase of Dismal Swamp Canal.

1929 Purchase is finally made for the same price as the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal, $500,000.

1933 Canal Dredged to 50 feet wide, 9 feet deep.

1933-1934 New U.S. 17 drawbridges completed at Deep Creek and South Mills.

1935 New Control spillway built on feeder ditch.

1940-1941 New concrete and steel locks built at Deep Creek and South Mills.

1974 Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge established by Congress. Navigational needs of the canal are made secondary to water conservation needs of the swamp.

1988 Dismal Swamp Canal placed on the National Register of Historic Places, and is also noted as a Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.

2000 Deep Creek Lock chamber dewatered and major repairs performed to the lock and gates.

2004 Dismal Swamp Canal included in the National Park Service's Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program.

a red light at the Deep Creek Bridge would warn drivers that the bridge was being raised to let a boat pass

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 091120-A-5177B-008

1934 bridge over Dismal Swamp Canal at Deep Creek, in the City of Chesapeake

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Cars over Deep Creek Bridge

the Federal government funded the replacement bridge at Deep Creek, so no tolls were required to repay bonds

Source: City of Chesapeake, Deep Creek AIWW Bridge Replacement Project

the annual Paddle for the Border on the Dismal Swamp Canal starts at the South Mills, North Carolina visitor center

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District Image Gallery

at times, the canal is exclusively a natural area without any people

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Corps announces timeline to reopen Dismal Swamp Canal

Links

- City of Chesapeake

- Dismal Swamp Canal Welcome Center

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Office of Coast Survey

- North Carolina Business History

- The Royster Guide to Northeast North Carolina

- US Army Corps of Engineers

References

1. Wilson Angley, David Stick, "Inlets," NCpedia, 2006, https://www.ncpedia.org/inlets; James C. Burke, "North Carolina's First Railroads, A Study in Historical Geography," PhD thesis, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 2008, pp.51-52, https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/Burke_uncg_0154D_10006.pdf; Kip Tabb, "Birth of Two Inlets: Accounts of 1846 Storm," Coastal Review Online, December 21 2017, https://www.coastalreview.org/2017/12/birth-two-inlets-accounts-1846-storm/; "North Carolina Canals - Dismal Swamp Canal," Carolana, https://www.carolana.com/NC/Transportation/dismal_swamp_canal.html (last checked October 13, 2020)

2. Byrd, William II, The Westover Manuscripts: Containing the History of the Dividing Line Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina; A Journey to the Land of Eden, A. D. 1733; and A Progress to the Mines. Written from 1728 to 1736, and Now First Published, p.16, http://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/byrd/menu.html (last checked January 5, 2019)

3. "Dismal Swamp Company," Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/dismal-swamp-company/; "History," Dismal Swamp State Park, North Carolina State Parks, https://www.ncparks.gov/dismal-swamp-state-park/history; "Deep in the Swamps, Archaeologists Are Finding How Fugitive Slaves Kept Their Freedom," Smithsonian Magazine, September 2016, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/deep-swamps-archaeologists-fugitive-slaves-kept-freedom-180960122/; "Historic Waterways, The Dismal Swamp and the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canals,"

US Army Corps of Engineers, https://www.nao.usace.army.mil/Portals/31/docs/civilworks/AIWW_Brochure_2011.pdf (last checked August 18, 2020)

4. Bland Simpson, "Dismal Swamp Canal," 2006, NCpedia, https://www.ncpedia.org/dismal-swamp-canal; James C. Burke, "North Carolina's First Railroads, A Study in Historical Geography," PhD thesis, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 2008, pp.64-65, https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/Burke_uncg_0154D_10006.pdf; "The Dismal Swamp Canal," Anchor: A North Carolina History Online Resource, https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/dismal-swamp-canal; Mathew Shaeffer, "Dismal Swamp Canal," North Carolina History Project, https://northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/dismal-swamp-canal/; "Dismal Swamp Canal and Associated Development, Southeast Virginia & Northeast North Carolina," nomination form for National Register of Historic Places, US Army Corps of Engineers, June 6, 1988, https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/131-5336_DismalSwamp_MPD_1988_NRHP_nomination_final.pdf; Ronald E. Shaw, Canals for a Nation: The Canal Era in the United States, 1790-1860, University Press of Kentucky, 1990, pp.117-120, https://books.google.com/books?id=hx2GqYSikMEC; "18th - 19th Century Canals in North Carolina," North Carolina Business History, http://www.historync.org/canals.htm; Peter C. Stewart, "Railroads and Urban Rivalries in Antebellum Eastern Virginia," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 81, Number 1 (January, 1973), pp.4-5, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4247766; "Herring (Heron) Ditch," Historical Marker Database, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=114521; "Historic Waterways, The Dismal Swamp and the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canals,"

US Army Corps of Engineers, https://www.nao.usace.army.mil/Portals/31/docs/civilworks/AIWW_Brochure_2011.pdf; "North Carolina Canals - Dismal Swamp Canal," Carolana, https://www.carolana.com/NC/Transportation/dismal_swamp_canal.html (last checked October 13, 2020)

5. "America's Civil War: Expedition to Destroy Dismal Swamp Canal," History.net, August 31, 2006, http://www.historynet.com/americas-civil-war-expedition-to-destroy-dismal-swamp-canal.htm; "The Great Dismal Swamp and the American Civil War," Thomas' Legion: The 69th North Carolina Regiment, http://www.thomaslegion.net/thegreatdismalswampandtheamericancivilwar.html (last checked January 6, 2019)

6. Bland Simpson, "Dismal Swamp Canal," 2006, NCpedia, https://www.ncpedia.org/dismal-swamp-canal; "Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal Historic District," nomination form for National Register of Historic Places, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, December 23, 2002, https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/VLR_to_transfer/PDFNoms/131-5333_Albemarle&Chesapeake_Canal_HD_2004_Final_Nomination.pdf (last checked January 3, 2019)

7. "Dismal Swamp Canal - National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form," US Army Corps of Engineers, December 1, 1987, http://www.cityofchesapeake.net/Assets/documents/departments/planning/Historic-Registry-dismal_swamp_canal.pdf (last checked January 1, 2019)

8. "Floating theater entertained crowds along Dismal Swamp Canal," The Virginian-Pilot, October 27, 2020, https://www.pilotonline.com/history/columns/vp-cp-james-adams-floating-1101-20201027-lenkmjxpwvhstmhkhaaejvucem-story.html (last checked October 28, 2020)

9. "Corps announces timeline to reopen Dismal Swamp Canal," US Army Corps of Engineers, May 17, 2017, https://www.nao.usace.army.mil/Media/News-Stories/Article/1185260/corps-announces-timeline-to-reopen-dismal-swamp-canal/; "AICW - Virginia Route Segment," BlueSeas, https://www.offshoreblue.com/cruising/aicw-va.php; "Dredging the Dismal Swamp Canal: Tens of thousands of gallons hauled away as crews rush to reopen waterway," The Virginian-Pilot, August 24, 2017, https://pilotonline.com/news/local/article_8caab998-8651-5458-9f33-b76dc2e19012.html (last checked January 1, 2019)

10. "Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway Deep Creek Bridge Replacement Project Fact Sheet," City of Chesapeake, http://www.cityofchesapeake.net/Assets/documents/departments/public_works/Projects/Deep+Creek+Bridge+FS.pdf

11. "Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway route closed for gate restoration," US Army Corps of Engineers - Norfolk District, January 13, 2020, https://www.usace.army.mil/Media/News-Archive/Story-Article-View/Article/2056263/atlantic-intracoastal-waterway-route-closed-for-gate-restoration/ (last checked August 18, 2020)

12. "Historic Waterways, The Dismal Swamp and the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canals,"

US Army Corps of Engineers, https://www.nao.usace.army.mil/Portals/31/docs/civilworks/AIWW_Brochure_2011.pdf (last checked August 18, 2020)

building the South Mills Lock in 1899, at the southern end of the canal

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Dismal Swamp Canal continues 85-year revival

the Dismal Swamp Canal supports recreational rather than commercial traffic now

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 100526-A-8647R-025

the Deep Creek Lock is at the northern end of the Dismal Swamp Canal

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 100526-A-8647R-020

the Dismal Swamp Canal is the oldest operating canal in the United States

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form

From Feet to Space: Transportation in Virginia

Virginia Places