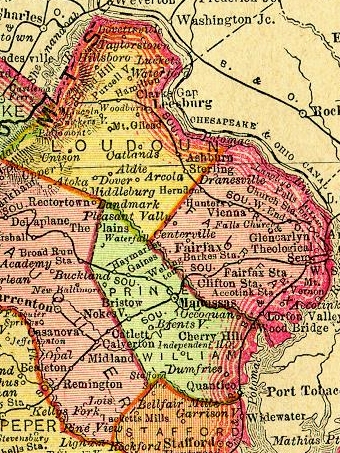

eastern Virginia in 1834

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the United States compiled from the latest and most accurate surveys by Amos Lay (1834)

eastern Virginia in 1834

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the United States compiled from the latest and most accurate surveys by Amos Lay (1834)

Virginia is not homogenous - not yet. Despite the impact of radio, television, and now the Internet, and despite the proliferation of national chains like K-Mart and McDonalds, there are still distinctions between the people in different sections of Virginia. Virginia evolved in fits and starts, and is now a mosaic of different "spaces" that together compose the Commonwealth of Virginia as we know it today.

There are lots of regional nicknames, and residents of Virginia refer to various regions of the state. There's no guarantee that any two people would agree on the boundaries of these "colloquial" regions, however:

In addition to the physiographic regions of Virginia, another way to carve up the state is to draw regional boundaries based on planning districts, as in The Nine Regions of Virginia by Jim Fonseca. However you draw the line, cultural regions share common characteristics that distinguish them in some way from other areas.

Until World War II, you could make an educated guess about a person's original home in Virginia by observing their distinctive accents, food preferences, and other patterns of behavior.

Today, bagels and Chinese take-out are common in Martinsville as well as Arlington. NASCAR is popular in Warrenton as well as Emporia. Sunday afternoon football is watched in Grundy as well as Virginia Beach, and people throughout the state type the same emoticons in text messages.

Still, there are differences between places and people in Virginia today. If you're in a Hardees in South Boston, notice the iced tea - odds are, it will be sweetened, unlike the iced tea in the Hardees at Fredericksburg. Manassas students debate whether the University of Virginia can beat Virginia Tech in football this year - or any year - while Danville students may follow the athletic successes of schools in North Carolina.

And while there are excellent Japanese restaurants in Roanoke and Garrison Keillor did Prairie Home Companion shows in the local coliseum, a Middleburg or McLean address will still carry far more social cachet - except in the West End of Richmond, where family name might carry more social weight than even the largest bank account.

If you're a "lumper" with a nostalgic perspective, you can say there's Northern Virginia (NOVA) and then there's everything else, the Rest of Virginia (ROVA). Typically, folks drawing this line are long-term residents who consider Northern Virginia to be an alien entity, "occupied" by Northerners and people with no family ties to Virginia

If you're a "splitter," perhaps responsible for an advertisement campaign where knowing the location of the target audience is essential, you can identify far more regions using additional characteristics to segment Virginia.

Hampton Roads can be split into the Eastern Shore, the Peninsula, and Norfolk/Virginia Beach. Splitting further can separate out Williamsburg/James City County, Newport News/Hampton, Suffolk/Chesapeake, Norfolk, and Virginia Beach. If you're doing direct mail advertising, you'll use Zip Codes to split down further to distinct neighborhoods.

If you're a politician, you'll split down to precincts since all politics is local. And if you're a Census enumerator, you'll try to find every single person in your Census block.

Northern Virginia - 1895

The boundaries of these regions of Virginia are permeable to migration of people and information. The current boundaries are poorly-defined, subject to debate, and perhaps likely to be outdated within a few decades. Virginia's political boundaries have also been subject to change. The state claims to the Forks of the Ohio (Pittsburgh area) were dropped in the 1760's. The claims to the Northwest Territory (Ohio, Indiana, Illinois...) were relinquished in the 1780's. Kentucky became a separate state in the 1790's, and in the 1860's the western 33 counties of Virginia split off to become West Virginia.

How should we draw the lines of the sections of Virginia, especially on a map?

There's always the physical geography to consider. Virginia's regions reflect transportation and population patterns established during the colonial era and prior to the Civil War. As the physical geography shaped those patterns, it created the modern regions of Virginia.

We are now witnessing a revolution in transportation, along with substantial growth in Virginia's population. The physical constraints affecting where people settle are far less important now. Electricity can be transmitted to any location in the state; locating an manufacturing facility near waterpower is no longer necessary. Highway engineers can tunnel and bridge most every natural barrier, and the Fall Line is irrelevant to international travel by airplane.

In a service economy, telecommunications lines reach to every corner of the state. Telephone operators in Norton handle "information, please" inquiries for the entire state. Postal workers in Roanoke read addresses scanned in Fairfax's Merrifield post office, adding a machine-readable bar code to speed sorting and delivery.

If we understand how Virginia's current cultural regions evolved, and calculate the factors that are changing our society now, we can estimate how Virginia's cultural regions will evolve over the next 20 years.

Dr. James Fonseca published "The Nine Regions of Virginia" in 1990. He identified nine distinctive subunits of the state, based on their shared interests and mapped by planning districts. Various organizations have carved Virginia into other subunits, primarily for administrative purposes or for the convenience of tourists.

We joke now about the Civil War being the "War of Yankee Agression" or "The Late Unpleasantness" while we wave the Star Spangled Banner and expect our elected Senators/Representatives to bring home the Virginia share of the Federal "pork" for military bases, Interstate highway construction, etc.

The idea of secession in Virginia is now a concept for fun or history, rather than a viable proposal. Accents and clothing styles reflect what people see in national television shows and national magazines, and homogenization of culture diminishes the regional differences.

After Chechnya, Kosovo, and East Timor, it's clear that understanding sectionalism and community, and what keeps a political unit intact, is more than an academic exercise. If you are an American Indian, Aleut, Eskimo, or Hawaiian native, or dealing with lands owned or claimed by those groups, you may consider nationality and independence to be fundamental, unresolved political issues.

After the Revolutionary War, John Marshall is reported to have said "I went into the army a Virginian, I came out an American." But obviously other Virginians defined Virginia as their nation, even after the adoption of the Constitution and the increased power it granted the central government in the Federal union of states. John Randolph (of Roanoke) said "When I speak of my country, I am referring to the Commonwealth of Virginia" - and Robert E. Lee made a fateful choice in 1861 as well...

Sectional differences in various Virginia regions are still identifiable today. Every candidate is in favor of better roads and schools (and lower taxes...), but votes on some "social" issues such as gun control can expose different policies advocated by candidates running for office in urban vs. rural areas. The results of a vote in on an amendment to the State Constitution in 2000 showed clear regional differences in the level of support for "Shall the Constitution of Virginia be amended by adding a provision concerning the right of the people to hunt, fish, and harvest game?" Statewide, the proposal received 60% support. Support was lowest in the Eighth District in Northern Virginia (only 43%) and highest in the Ninth District in Southwest Virginia (76%).

Northern Virginia has gained a reputation as a liberal region in the last century, and as the high-tech "dot.com" region in the last 15 years. Some of the liberal philosophy was based on the attitudes of Quaker farmers who settled in Loudoun County before the Civil War. Their lack of support for the Confederate cause did not protect their barns from the "burning raid" of the Union forces, however. After that war, former Union officers settled in some sections of Northern Virginia such as Manassas - but then again, Chase City in Southside was also settled by "Yankees" after the war.

Southside has traditionally been perceived as a particularly conservative region, especially during the civil rights debates. Though most racism and segregation in Virginia during the middle third of the 20th Century may have been in the urban cities, the most overt act of segregation in the state was the closure of the Prince Edward County schools for four years.

Prior to the Civil War, there were more black staves than free whites in many counties in this region. Nat Turner's rebellion (1831, in Southampton County) spurred a tightening of the institutional racism, and echoes are still easy to find. In the 1999 sheriff's race in that area, charges of unequal treatment for the black candidate once again focused attention on issues of equality and status that dated back to the mid-1600's.

In 1954, the Supreme Court mandated the end to separate-but-equal school systems in the Brown vs. Board of Education. One plaintiff was from Prince Edward County in Southside. When the Byrd Machine's policy of Massive Resistance to the court order finally crumbled in 1959, the county responded by closing its public school system completely. A whole generation of students who should have gone from freshmen to graduation in a public high school between 1960-64 was excluded from education, forced to move away to attend school, or treated to substandard classrooms cobbled together in church basements and hastily-built segregation academies.

When State Senator Douglas Wilder decided to run for Lieutenant Governor, he was almost ignored as an unlikely underdog. He was a divorced black man, running for statewide office 30 years after Massive Resistance. His legislative record in the State Senate did not set him apart as a particularly effective leader. The traditional Democratic leaders did not support his candidacy, and worried that it would drag down the rest of the ticket by stimulating voters with religious and racial concerns to vote Republican.

Wilder confronted the issues by getting away from the media centers of the state, and going to Lee county to start his campaign. He drew surprising attention from local Democratic leaders and activists, in part because of the unaccustomed attention and a desire by Southwestern Virginians to be seen as hospitable rather than hostile. With a charming style and a sharply-edged campaign suggesting any opposition to him was spurred by racism, Wilder won commitments from more and more old-style Byrd Democrats during his campaign swings.

But perhaps his most important achievement was to win the backing of A. L. Philpott, a pillar of conservatism in Southside. Danville was the last capital of the Confederacy, and Wilder knew the challenge. He confronted it head-on. One crowning moment in the race was the campaign commercial featuring a deputy sheriff from Dinwiddie County. If you remember Rod Steiger's classic tobacco-plug-in-the-cheek performance in the movie In the Heat of the Night then you get the idea of the appearance of the officer - and the visual impact of the television commercial highlighting his endorsement of Doug Wilder. The Friends of Police organization considered Wilder to be tough on crime, and that conservative stance helped immunize Wilder against a racist rejection.