Regions of Virginia Defined by Watershed Boundaries

|

East of the Blue Ridge, we tend to define our place by highways or political boundaries. People know their mailing address, their e-mail address, the nearest Interstate highway and the name of their county or city - but it's hard to find someone who

knows their watershed address and where the water goes from their front yard.

Some might identify themselves as living in Tidewater or recognize they are in the Chesapeake Bay watershed -

but even after you explain the concept of a watershed, many will say "I never thought about it." Northern, Central, and Southwest Virginia are regions defined by the edges of the state's external boundaries, not by watersheds. Next time you hear someone refer to Southside Virginia - see if they can identify the river that defines the northern boundary of that region...

- True, you can find wealthy Richmonders with a cottage on the "rivah" who know which river, but ask them if their house

is in the Chicahominy River watershed. (If they live in the West End north of Cary Street Road, it probably is - but if they live south of the James, then it's not.)

Those residents in Bedford County who built cabins on Smith Mountain Lake are likely to know that the lake was formed by damming the Roanoke River,

but ask them if the river meets the ocean in Virginia, North Carolina, or South Carolina.

It's different in the Blue Ridge, on the Allegheny Plateau, and in the valleys and ridges between them. It's far easier

to find people there who define their location by reference to a ridge or valley - particularly the Shenandoah and Roanoke valleys. On a small scale, in the rural countryside of the Blue Ridge people commonly know their neighbors

as fellow residents of Madison Run or Possum Hollow. Where the roads from the flatlands split

off from another and climb into the valleys before they dead end at the Blue Ridge, people are still conscious of

their watershed. But ask around, and see how many people know the sequence of the creeks and rivers

that carry rainwater from their doorstep all the way to the ocean.

Signs have been posted on Interstate 81, and storm sewer drains have been

spray-painted with "Chesapeake Bay Watershed" in Arlington in order to sensitize residents about where their

pollution goes. When it goes out of sight, it should not go out of mind. Someone else will be on the receiving end....

This ignorance is a reflection of the power we control with an automobile and the extraordinary

construction of easy-to-drive highways in the last 70 years. Watersheds no longer affect our transportation

routes, with a few exceptions. Once Henry Ford started mass-producing cars with high horsepower, and Governor

Harry Byrd committed the state in the 1920's to a pay-as-you-go highway construction program, Virginians

have been able to sit comfortably behind the wheel and ignore physical boundaries like watershed divides.

Though we may not be concious of them, watersheds have shaped the interests of different regions in Virginia.

The Radford/Blacksburg area of Southwestern Virginia, there is a summertime drama that

highlights the impact of

watersheds in determining what Native Americans were located in that area in the 1750's.

"The Long Way

Home" is the tale of the Shawnee capturing Mary Draper Ingalls and her sister-in-law from

what is now the

center of the Virginia Tech campus. Why were the Shawnee in the area?

Simple - go downhill from the Drill Field and Duck Pond on the Virginia Tech campus. You'll

find yourself

traveling west, down the New River, to the Ohio River. The Shawnee lived on the Ohio, and

carried Mary Draper

Ingalls to their villages in that watershed. In the 1750's the Shawnee were hunting throughout

their watersheds.

When the English crossed into the New River Valley and settled in Shawnee hunting territory, the

conflict between

the two cultures was brief but intense.

When Mary Draper Ingalls finally escaped from captivity, she walked home by following the New

River back to

her cabin. When she encountered side streams too wide to cross, she walked upstream along the

tributary, found a

shallow spot, and returned to the main stem of the New River so she knew where to go. It was a

400 mile journey,

done in 40 days in October/November - worthy of a dramatic retelling. Like the Shawnee's

hunting trips, her

journey was shaped by the boundaries of the watershed.

The watershed boundaries in the eastern part of Virginia were significant for the English settlers

at the start of the

Virginia colony in the 1600's. The plantations on the lower Chesapeake had economic advantages

over those

further north. Ships from England would sail through Cape Charles and Cape Henry into the

Chesapeake Bay,

and go first to wharfs along the James or the York rivers. Plantations further away on the

Potomac River were

visited less-often by the ships that transported tobacco to Europe.

|

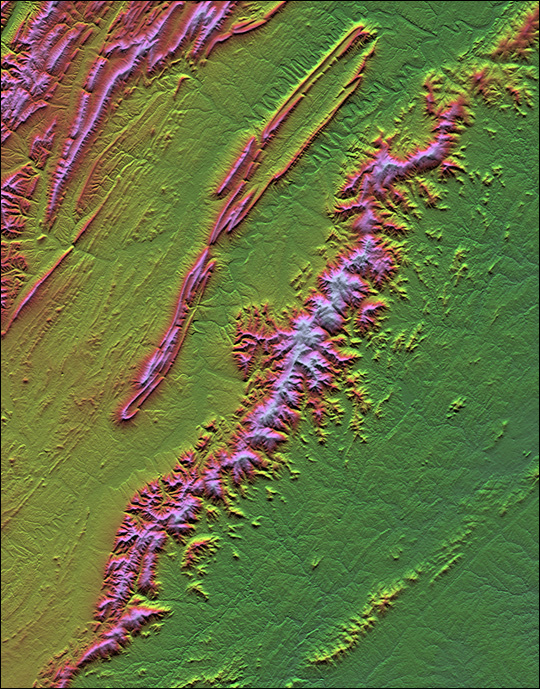

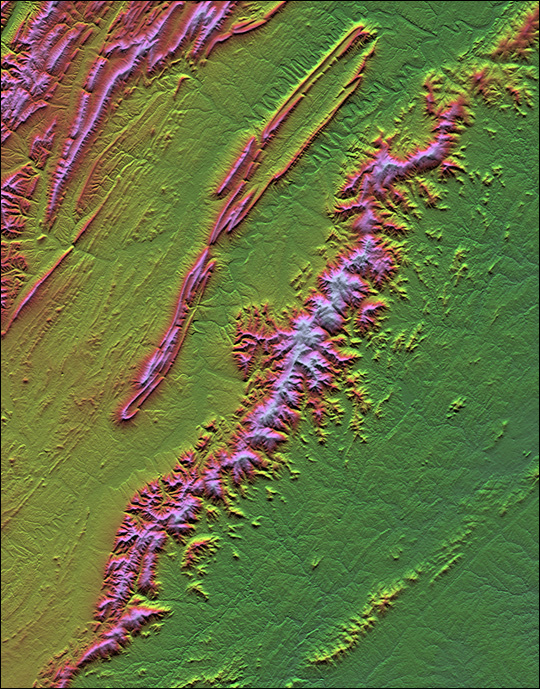

radar-generated topographic image - Shenandoah Valley and Blue Ridge

Source: NASA |

In 1759, George Washington acquired extensive lands on the York River - along with the slaves

who grew the

tobacco there - through his marriage to Martha Custis. In the York River watershed, ship

captains arrived on a

reliable schedule and would accept all the hogsheads of cargo available from his plantation

wharves. However, in

the Alexandria area of the "upper" Potomac, Washington had to work harder to find a ship that

would load all the

tobacco when he was ready to ship it. More than once, items that Washington ordered from

England for delivery

at Mount Vernon were deposited instead at a wharf on the York. This delayed delivery, of course

- and by the time

the packages from England were actually re-shipped by a local vessel (or even carried by wagon)

to northern

Virginia, the goods were often damaged.

- Perhaps one reason Washington shifted from tobacco to food grains at his five Mount

Vernon farms was his

frustration with transport. Washington continued to grow tobacco as a cash crop in the York

watershed

throughout his life, where he could manage the sales and shipment of each year's crop more

reliably.

- Washington was capable of growing a fine crop of tobacco, in a day when a plantation

owner's reputation

was based on his skill as a "tobacco master." But Washington, though always sensitive about his

reputation, was

also a businessman. He realized could make a profit growing wheat at Mount Vernon, in part

because he could

ship it to other locations within the colonies and thus be independent of London brokers and

cross-Atlantic ship

captains.

The ratification of the Constitution by Virginia in 1788 also hinged on sectional interests based on

watershed

boundaries. Adoption of the replacement to the Articles of Confederation was a close vote.

Patrick Henry and his

allies opposed ratification, fearing that the efforts to eliminate English domination would be

replaced by excessive

controls and limits on freedom by another centralized government. James Madison and his allies

(including

George Washington, offering support quietly from Mount Vernon), struggled to find the right mix

of arguments

and political favors to win support from a majority of delegates to the special convention in 1788.

Madison identified the key to winning the support of the representatives from the Kentucky

counties. He

convinced them that a central government based on the proposed Constitution would be more

effective in getting a

guarantee of free trade down the Mississippi River and through New Orleans (which was

controlled at that time by

the Spanish). Kentucky residents on the frontier had no strong love for the tax-collecting state

government in

Richmond or the national government in Philadelphia, but they voted for ratification in order to

protect their

watershed-defined trading interests.

Throughout his adult life, George Washington was very sensitive to the potential

of the western settlements choosing to break away from the colonies on the Atlantic

coast. Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, was quick to act when he

recognized the threat of the French settling the Ohio River valley in the early

1750's. The French arrived at the Forks of the Ohio by following the St. Lawrence

River upstream, past Quebec and Montreal, crossing through Lake Ontario and

Lake Erie, then traveling over the watershed divide into the headwaters of the

Allegheny River.

Dunmore dispatched a 21-year old George Washington to the French winter camp in late 1753, to

assert the

validity of Virginia land grants in the Ohio Valley and to tell the French to leave British territory.

Dunmore knew

that if the French were able to extend their Canadian colonization into the Ohio River valley, and

link it with their

Mississippi River claims at New Orleans, then English settlement would be restricted to the

Atlantic coast... and

Dunmore's opportunity to get rich from western lands would be diminished.

Washington was a strong supporter of canals to link the western settlements with the Eastern

Seaboard. He looked

for a way to transport Western crops, lumber, items manufactured at iron works, and other

products to the East

Coast rather than allow trade to develop naturally, downstream to St. Louis or New Orleans.

Washington and his

fellow investors calculated that canal boats could link east and west together economically, using

trade to reduce

the incentive for separatist movements and to create a sense of common American identity.

Proposals in the early 1800's to build canals in the Potomac and James watersheds showed how

rivers could define sections of Virginia. Both canals were intended to unite Tidewater ports with

the Ohio River watershed. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal would benefit Alexandria and

Northern Virginia, while the James River and Kanawha Canal would provide equivalent benefits

to Richmond and central Virginia.

The General Assembly voted for the obvious compromise. Instead of financing one canal, using

taxes from throughout the state to benefit just one section, the politicians voted to support state

financing of both canals. In part as a result of the state officials failing to choose a winner and a

loser, both projects suffered from undercapitalization. Ultimately, the slow construction of the

canals was their doom, as a new technology (railroads) made canals uneconomic before they were

completed.

Political parties developed in the 1830's. When the Democrats were in power, they would vote

for transportation improvements in the central Virginia watershed. When the Whigs were in

control, projects tied to the Potomac would benefit from state financing. In the end, Virginia

spent far more money than was justified, balancing investments so the two Tidewater regions

received equivalent support.

Left out of the process was the Ohio River watershed. Nearly all investments in "internal

improvements" financed by the Board of Public Works were made east of the Allegheny Front, in

the Chesapeake Bay watershed. The decisions on what to support reflected the unequal

representation of counties in the General Assembly. Tidewater had fewer white males than the

counties west of the Blue Ridge - but the numerous, small eastern counties elected more

representatives than the few, large western counties. Not until the state constitution was revised

again in 1851 did the residents west of the Blue Ridge gain control of the House of Delegates -

and they never captured control of the State Senate.

The Tidewater politicians did not want better roads or canals leading westward to the Ohio.

Virginia trade would then be carried downstream to the largest city in the South, New Orleans.

So western Virginians paid high taxes on their property (mostly land), while Eastern Virginians

paid low taxes on their propert (mostly slaves). Eastern Virginia reaped the benefits of the

Bureau of Public Works financing, and the westerners grew so disenchanted that they split the

state in two during the Civil War.

Had the Cheat, Greenbriar, Kanawha, and Tug rivers flowed east instead of west, or had the

politicians in the 1800's shared George Washington's concerns for using transportation

improvements to establish political and economic unity, then Wheeling might still be in Virginia...

How Watersheds Define the Boundaries of Virginia

Regions of Virginia

Virginia Places