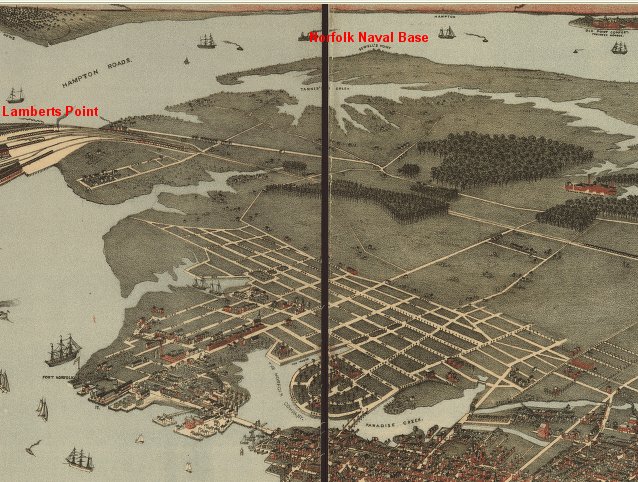

Bird's eye view of Norfolk, Portsmouth and Berkley, 1891

(note how rural the area was a century ago between the railroad's coal terminal

at Lamberts Point and the modern Norfolk Naval Base at Sewalls Point)

Source: Library of Congress

The failure of Virginia to develop urban centers before the American Revolution reflects the transportation and settlement patterns of the colonists, as well as the topographic barrier created by the Fall Line.

The Chesapeake Bay provides a heavily-indented coastline; ocean-crossing ships can dock at numerous places throughout Tidewater Virginia. The English relied upon the rivers for cargo transportation throughout colonial times.

By the end of the 17th Century, Tidewater planters with extensive land grants had established a pattern of adding new "quarters" (farm units where slaves grew primarily tobacco under direction of an overseer, away from the mansion house) further and further up the Chesapeake tributaries, rather than concentrating in one urban location. Those growing tobacco further inland, away from the rivers, would ship it to England by rolling the hogsheads to the nearest plantation with a wharf. Because there were many plantation wharves throughout Tidewater, the "rolling roads" did not lead to any central place.

By the time European settlement reached the Great Falls of the Potomac River in the 1730's, Virginia was an decentralized agricultural colony, growing one staple crop on separate plantations. The gentry who controlled the weath of the colony, such as George Washington, would often ride to the fields from their individual mansion houses to observe the quality of the tobacco crop and the labor of the indentured servants (in the 1600's) or slaves (the primary labor force in the 1700's). The gentry practiced "parallel processing" agriculture, using the same technology in different locations to create the same product for export.

Jamestown, from the beginning, was an international city. Ship captains, sailors, emigrants from various nations, and slaves imported against their will created a cultural mix with a little of everything. But Jamestown, and later Williamsburg, never grew like Boston, Philadelphia, or New York. Instead of one primary city providing most services needed by the colony, Virginia plantations developed as largely self-sufficient communities.

The Virginia colony was the primary source of revenue from America, due to taxes on the tobacco. London wanted the colony to develop towns, centers of population where it would be easy to monitor tobacco shipments and assemble the militia for military defense against Spanish raids or Indian attacks. Royal governors were ordered to stimulate city development, in part to reduce the potential of ship captains sailing directly to Virginia plantations and smuggling tobacco directly to Holland or France.

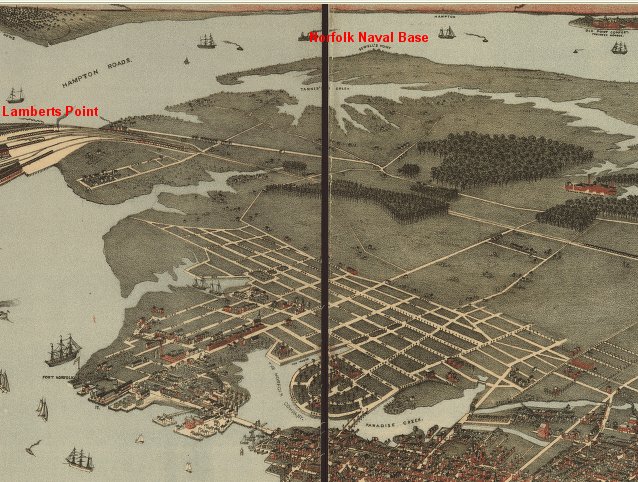

Bird's eye view of Norfolk, Portsmouth and Berkley, 1891

(note how rural the area was a century ago between the railroad's coal terminal

at Lamberts Point and the modern Norfolk Naval Base at Sewalls Point)

Source: Library of Congress

In Virginia, Norfolk grew into the largest city before the Revolution due to it's fine natural harbor and shipbuilding industry. However, there were few reasons for the Virginians to build towns elsewhere. Thanks to the Chesapeake Bay's extensive shoreline and Virginia's agricultural economy, farm implements, cloth, sugar, luxury goods, etc. could be imported directly to a plantation from Europe or the West Indies. In other colonies, however, delivering crops to market or imports to people required unloading a ship and hauling the products via wagon inland. Cities like Charleston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston provided that service.

The limited role of Virginia government also limited the potential of county seats to grow into urban centers. Courthouses were for monthly "court days" but were not the bustling business centers of today. The counties staggered their schedules so lawyers could ride a circuit - Monday in Louisa, Wednesday in New Kent, etc.. Patrick Henry and others traveled from county to county to argue cases in local courts. Only Williamsburg, with it's quarterly General Court meeting for appeals, could provide sufficient business for a lawyer to be able to stay in one place.

Even the capital city was just a place to visit. There was no army of bureaucrats in Williamsburg, equivalent to the Federal employees filling the Northern Virginia suburbs today. The elected representatives were wealthy plantation owners who by the mid-1700's lived most of the time in their brick mansions in Tidewater, managing their business affairs from a home office. They would travel to Williamsburg for meetings of the House of Burgesses or Governor's Council, but then return home.

Some of the gentry did maintain a house in Williamsburg for use during their visits, and that town attracted a few people with specialized skills. Williamsburg is perhaps the best example of colonial Virginia development following Walter Christaller's "central place theory." The only Virginia newspaper to be published in colonial times, the Virginia Gazette, was started in Williamsburg in 1732. Silversmiths, watchmakers, gunsmiths, and other specialists concentrated there, and served the entire colony from that location. The specialists catered to the Virginia gentry, and today the craftspeople in the reconstructed Williamsburg still demonstrate the skill required to create certain products.

But the next time you visit Colonial Williamsburg, look at the flag above the Governor's Palace. It shows where most of the specialists were located - in England. In the mercantile system of the colonial times, English cities were the central places with specialized capabilities to meet Virginian needs. Transatlantic ships coming to individual plantations were the equivalent of the brown UPS trucks delivering packages to individual houses today...

The American Revolution alone would not have changed that pattern. Specialists in France and Holland, and ships from those countries, were equally capable of suplying Tidewater Virginia's needs. Travel across the Atlantic was so common, and travel on Virginia's roads was so difficult, that delivery from Europe was as satisfactory as ordering from Williamsburg. Only after the population moved across the Fall Line, away from the easy access to international shipping, did Virginia start to develop its own urban centers.