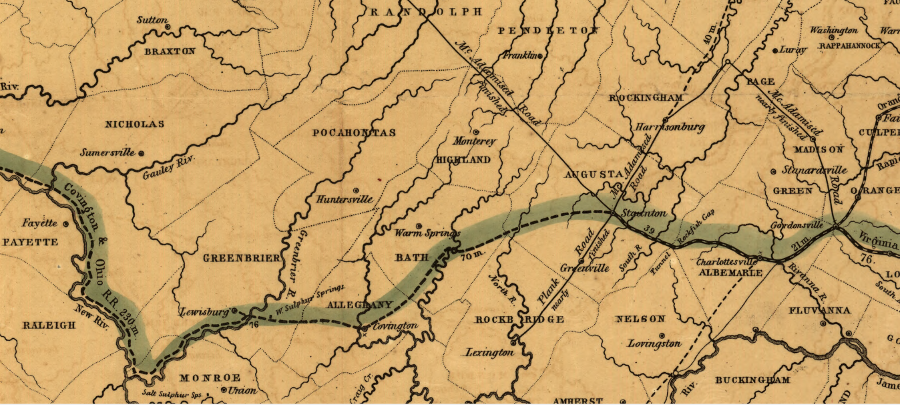

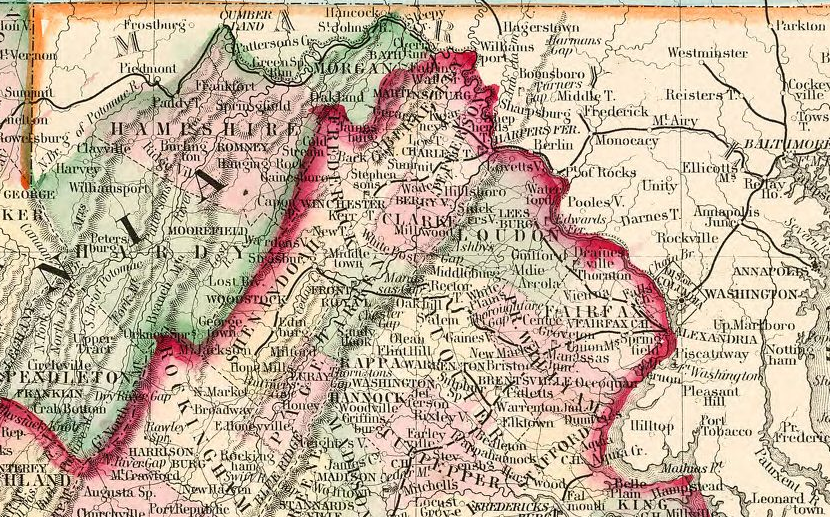

Virginia stretched to the Ohio River until 1863

Source: Boston Public Library, Norman B. Leventhal Map Center Collection, Virginia (Mathew Carey, 1806)

Virginia stretched to the Ohio River until 1863

Source: Boston Public Library, Norman B. Leventhal Map Center Collection, Virginia (Mathew Carey, 1806)

Sectional disputes in Virginia have included intense conflicts between northern Virginia (once owned by Lord Fairfax) and the rest of Virginia south of the Northern Neck, bitter competition between Richmond/Petersburg and Norfolk (including Petersburg arranging for the physical destruction of a railroad that diverted Roanoke River basin traffic to Norfolk), and expensive rivalries between Potomac River vs. James River communities that led the state towards bankruptcy due to excessive investment in competing canals/railroads.

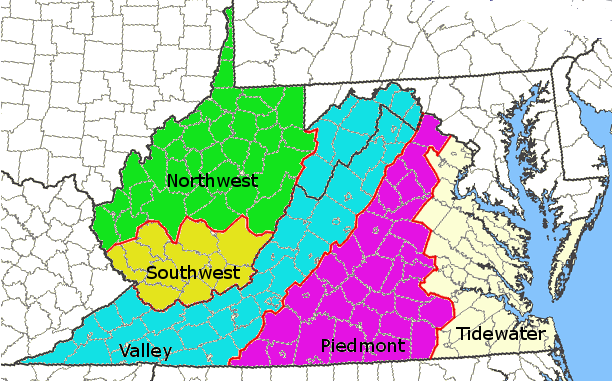

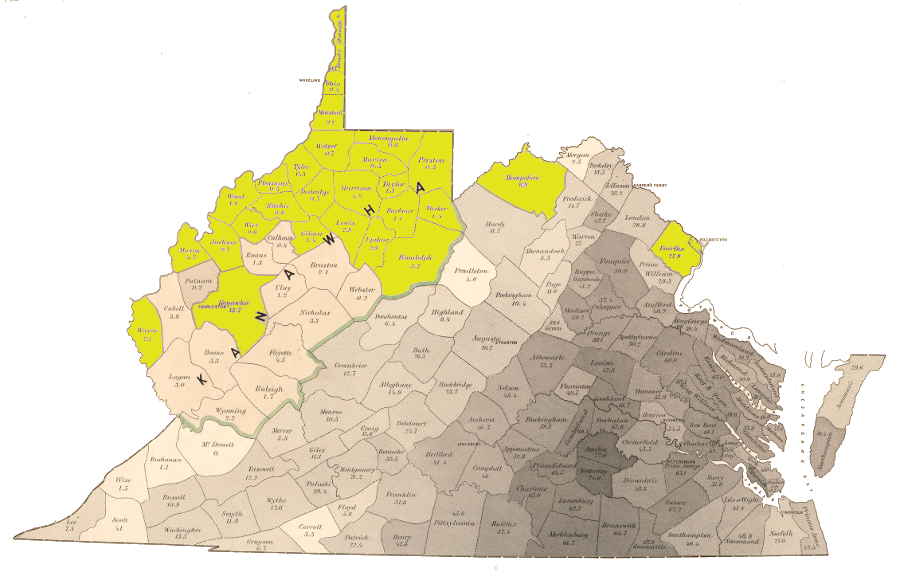

Only twice have those sectional disputes resulted in the division of Virginia, forming separate states. Virginia officials ultimately sponsored the conversion of its southwestern county of Kentucky into a new state in 1792. In contrast to the creation of Kentucky, the formation of West Virginia was more acrimonious. After Virginia seceded from the Union, the western counties essentially seceded from Virginia, ultimately reducing the size of "old Virginia" by over 1/3.

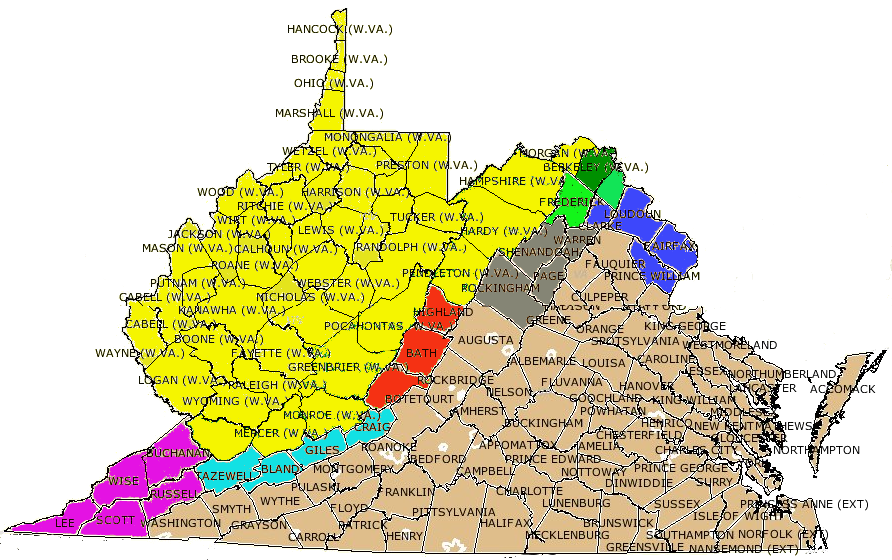

in 1860, the Trans-Allegheny District of western Virginia was divided into Northwest and Southwest districts

Map Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Atlas

On April 16, 1861, three days after the fall of Fort Sumter in South Carolina, the New York Times predicted that Virginia would split if the state seceded:1

The question was not "will the western part of Virginia split off" but "where will the new state boundary be drawn?"

At various times throughout the tumultuous years of 1861-62, different names were proposed for the new state. Kanawha, Alleghany, Columbia, New Virginia, and Augusta were considered before "West Virginia" was finally adopted. The initial favorite, Kanawha, was dropped in part because there was already a county and a river with that same name.2

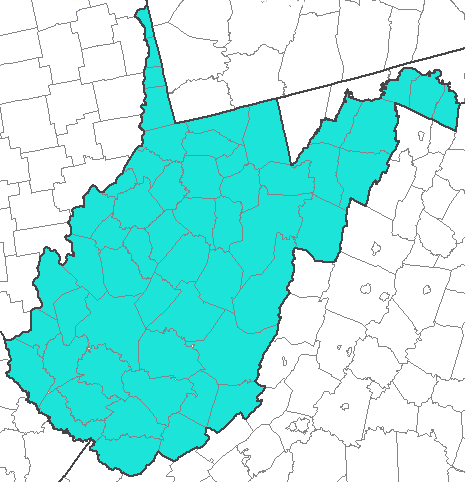

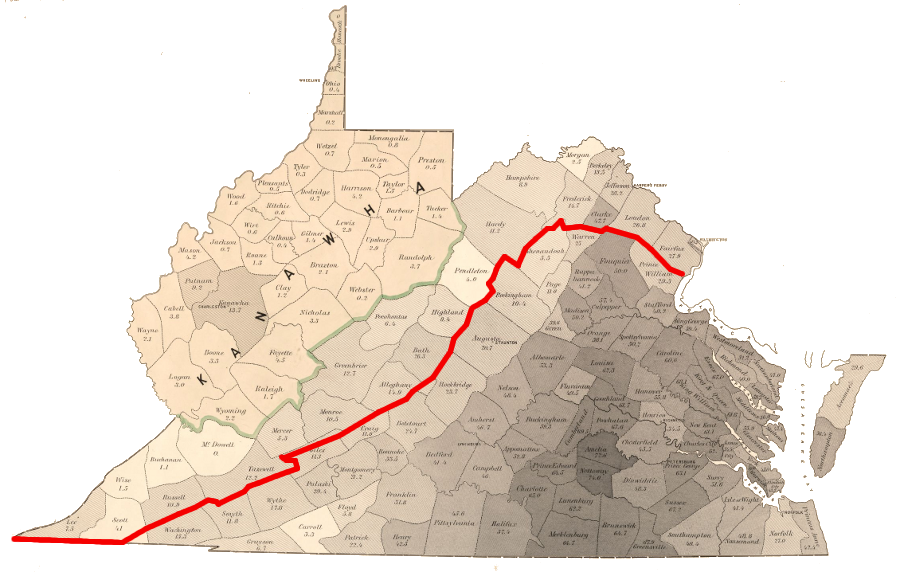

Creation of the West Virginia/Virginia border required multiple elections in the middle of a Civil War, two "state" conventions filled with debate, a US Senate vote opposed by the West Virginia Senator who originally proposed creating the new state, a decision by President Lincoln to override objections by half of his cabinet, and a Supreme Court decision validating an irregular election. In the end, 50 counties would be incorporated into a new state, and 99 counties would be left behind in the remnant of Virginia.

Modern West Virginia has 55 counties, since Mineral, Grant, Lincoln, Summers, and Mingo counties were created after statehood by dividing territory of existing counties. Modern Virginia has 95 counties. Since West Virginia was created, Dickenson County was created and five counties - Elizabeth City County, Nansemond County, Norfolk County, Princess Anne County, and Warwick County - have been incorporated into the independent cities of Hampton, Suffolk, Chesapeake, Virginia Beach, and Newport News.

There were many twists and turns throughout the process that defined which counties, or portions of counties, would split off to form a new state. Debates over the boundaries of the new state were long and emotional, with many alternatives considered. In some proposals during the 1861-62 debates, Fairfax County and Alexandria County (today's Arlington County/Alexandria City) would have been peeled off from Virginia and added to the new state. One option at the end of 1862 proposed Loudoun, Fairfax, Alexandria, and the Eastern Shore counties of Accomack and Northampton could join with the western counties to form a new West Virginia that would surround "old Virginia" on three sides.

modern West Virginia was 38% of Virginia's land area in 1861,

24,038 of Virginia's 63,528 square miles (now shrunk to 39,490 square miles)

Map Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Atlas

Representatives from western Virginia counties went to Richmond and participated in the Secession Convention in February-April, 1861. After President Lincoln called for volunteers in response to South Carolina seizing Fort Sumter, the convention voted to propose secession, and scheduled a statewide vote to confirm Virginia would leave the Union.

The northwestern counties of Virginia responded by holding meetings in Wheeling. After Virginia voters approved secession, the new Confederate government moved its capital to Richmond. In the midst of the Civil War that erupted, the western Virginians who opposed secession claimed to be the legitimate government of the state and completed the process of forming a separate state - West Virginia.

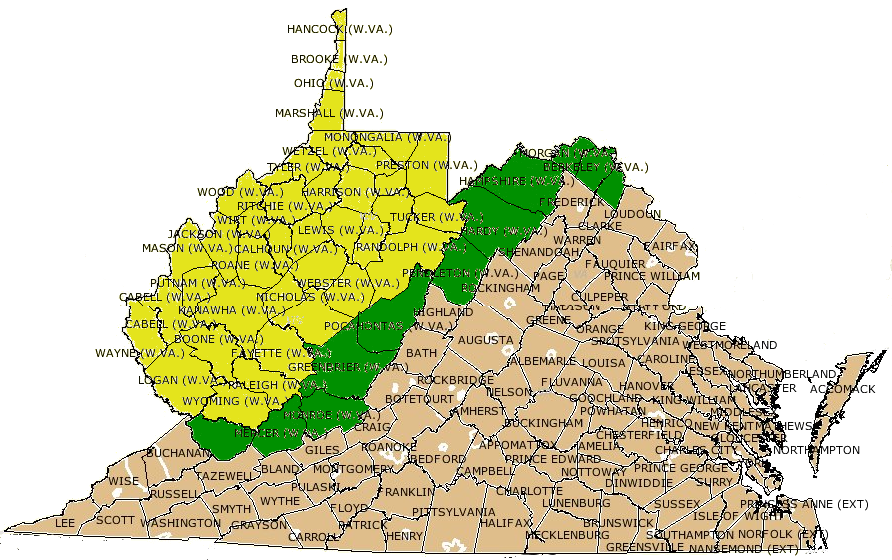

original 39 counties (yellow) included in August 20, 1862 Dismemberment Ordinance to create the new state to be named "Kanawha," and later additions (green) to form modern boundaries of what became "West Virginia"

Map Source: Newberry Library, Virginia Historical Counties

In June 1861, the Second Wheeling Convention (June Session) formed the Restored Government of Virginia as an alternative to the Confederate state government in Richmond, and elected Francis Pierpont at the new governor. While most participants in the Second Wheeling Convention (June Session) were from west of the Blue Ridge, Alexandria was occupied by the Union Army.

Perhaps with optimistic hopes that other parts of eastern Virginia would recognize the Restored Government based in Wheeling, rather than the secessionists based in Richmond, the convention declared that any state taxes collected east of the Blue Ridge would be deposited into the Bank of the Old Dominion in Alexandria.3

One-third of the counties that ultimately formed West Virginia had no representatives at the Second Wheeling Convention.4

During the Civil War, many county elections to select the officials who drew the new Virginia-West Virginia boundary were irregular and decisions to accept credentials of delegates were judged based on different circumstances. Even today, despite multiple court decisions, legal scholars continue to debate the legitimacy of the process used to establish the new state and its boundaries.

when the USS Monitor and CSS Merrimack dueled in the first battle of ironclad warships, Wheeling was still part of Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Wheeling (Virginia) Daily Intelligencer (March 13, 1862)

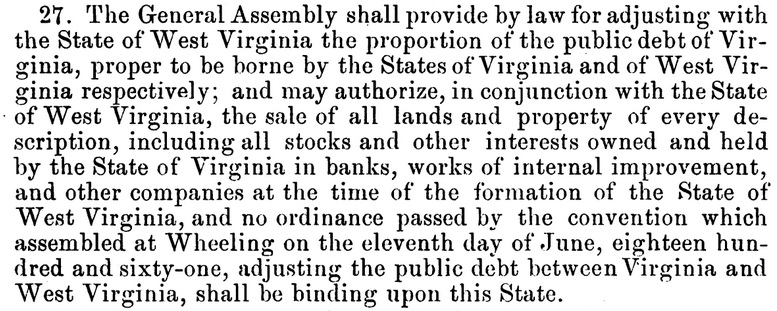

Debates regarding state boundaries and emancipation issues were resolved by 1866, but the complex issue of splitting responsibility for the pre-1861 Virginia state debt was not resolved until a Supreme Court decision in 1911. Final payment was not made until 1939.5

When western leaders first proposed a new state, splitting the debt was considered. One proposal was for the new state to accept no responsibility for the existing debt incurred by Virginia for roads, canals, railroads, and other public obligations.

Most of that debt had been used to finance transportation improvements in the eastern portion of Virginia. Frustration over how state taxes had been raised in the western region but spent in the east, and how the voting structure guaranteed eastern dominance, pushed the western counties to form a new state. (Only in 1911 did the US Supreme Court determine how much West Virginia owed "old" Virginia for its share of the pre-war debt, and it took until 1939 for West Virginia to finish paying.)

Those sectional differences went beyond support for the "peculiar institution" of slavery. After the Civil War ended in Confederate defeat and the 13th Amendment was ratified ending slavery, Eastern Virginia lost its status as a state. The former Confederate state was organized as Military District No. 1, and Congress controlled Virginia's re-admission into the Union. In this time period, the western counties could have reunited with the eastern counties to re-form an intact, slave-free Virginia. Instead, West Virginia chose to remain as an independent state.6

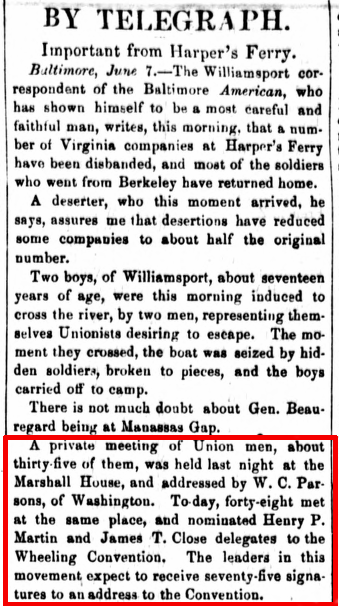

At the two sessions of the Second Wheeling Convention in June/August 1861, Henry S. Martin and James T. Close from Alexandria County (now Arlington County and the City of Alexandria) and John Hawxhurst and Eben E. Mason from Fairfax County participated. Jonathan Roberts arrived in Wheeling to represent Fairfax in the August session, but despite an endorsement by John Hawxhurst the convention rejected Roberts' credentials and refused to let him participate.7

When Rev. William F. Mercer from northern Loudoun County sought to represent that county in the Second Wheeling Convention (June Session), his credentials were not accepted. The election of Loudoun delegates was described as unrepresentative of the whole county, though only 35 people had participated in the Alexandria election. The B&O Railroad may have been working at this early stage to define boundaries for a new state that would exclude the area near the District of Columbia that was served by the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire Railroad.8

newspaper report of Alexandria County representatives elected to Second Wheeling Convention (June Session)

Source: Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, The national Republican (June 8, 1861)

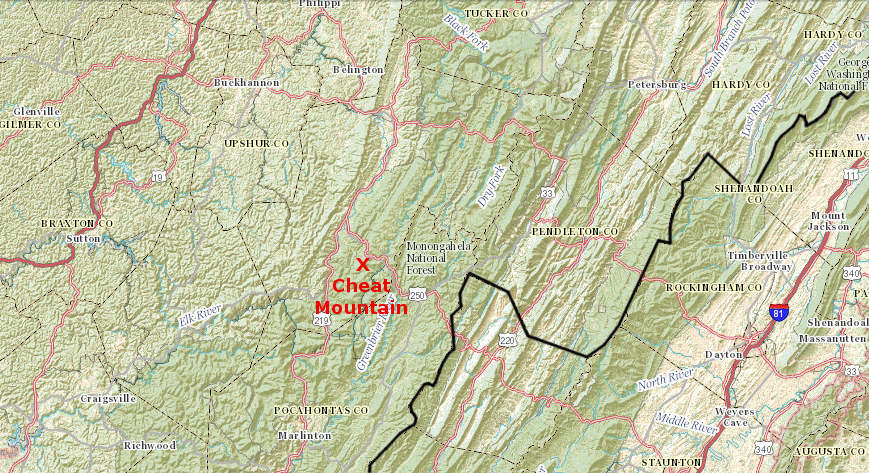

By the time the "Adjourned Session" of the Second Wheeling Convention met in August 1861, the split between the Union in the north and the Confederacy in the south threatened to become permanent. The Confederate Army had decisively won the first large battle of the war at Manassas, but was losing the war in western Virginia. The Union Army had seized the corridor of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Further south, it had recently occupied the Kanawha River valley as far east as Cheat Mountain, to block any Confederate advance on the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike.

There was the potential that any boundary drawn to split Virginia could become a permanent new national boundary dividing two independent nations. Proposed southern and eastern boundaries of the potential new state varied widely for two years. The rebel-against-the-rebellion-in-Richmond interest was concentrated in the northwestern corner of Virginia, and the new state could have been established as just "Northwest Virginia."

after the Battle of Cheat Mountain (September 1861) and the failure of General Robert E. Lee's Northwest Virginia Campaign, the Confederates largely abandoned the Allegheny Mountain region

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), The National Map

At the August "Adjourned Session," advocates for creating a new state were clearly in the majority. The counties in the secessionist two-thirds of "old Virginia" would not be changing their mind, abandoning the Confederate government in Richmond and committing to the Restored Government based in Wheeling in order to rejoin the Union. The counties that formed the one-third of Virginia in the northwest could wait until the secession movement was defeated, and reunite with the rest of Virginia back into the Union as an intact state. That, of course, might take years to occur - as it did.

By the "Adjourned Session," the benefits of creating a new state were clear. The northwestern counties would finally be able to broaden the electorate to allow more voters, draw election districts to reflected the patterns of population, create a fairer system of taxes, and ensure internal improvements would benefit the region. The advantages for the US Congress (and the Republican Party) were that a brand new state would clearly support the Union cause rather than the Confederacy - and if the boundaries were drawn a certain way, the new state might be willing to abolish slavery.

On August 7, the convention created the Committee on a Division of the State to propose where to draw the dividing line to split Virginia. The committee included John Hawxhurst of Fairfax and Gilbert S. Miner of Alexandria (presumably replacing Henry S. Martin). The vast majority of members appointed to the Committee on a Division of the State came from northwestern counties with a small percentage of slaves and with strong economic ties to Northern businesses, based on Ohio River or Baltimore and Ohio Railroad trade - plus Alexandria and Fairfax counties.

counties (yellow) from which members were appointed on August 7, 1861 to the Committee on a Division of the State

Map Source: Library of Congress, Map of Virginia: showing the distribution of its slave population from the census of 1860 (June 1861)

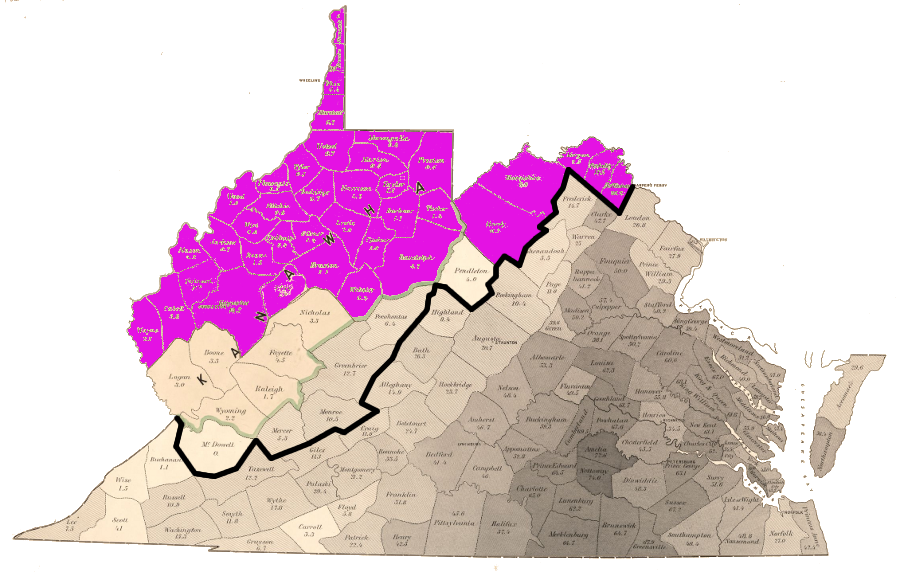

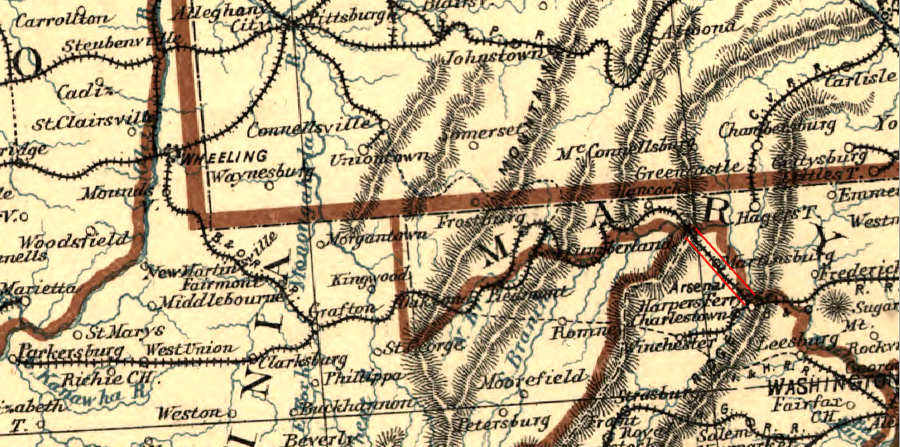

The Committee on a Division of the State reported back on August 10; debate on the committee's proposal started on August 13. However, John S. Carlile, a prominent pro-Union leader in the western counties and ultimately one of the Restored Government of Virginia's first two Senators seated in the US Congress, was unwilling to wait for the committee to even get started, much less produce a report. Carlile started a debate on August 8 by proposing boundaries of a small new state, limiting it to just the strongest pro-Union portion of Virginia - plus one strategic transportation corridor.

His boundary would have including all but one of the Northwestern portion of the Trans-Allegheny Division of Virginia (excluding Nicholas County), but only five more counties - all on the northern edge of the Valley Division. His dividing line omitted much of the upper Kanawha River watershed, which was still occupied by Confederate troops until September 1861.

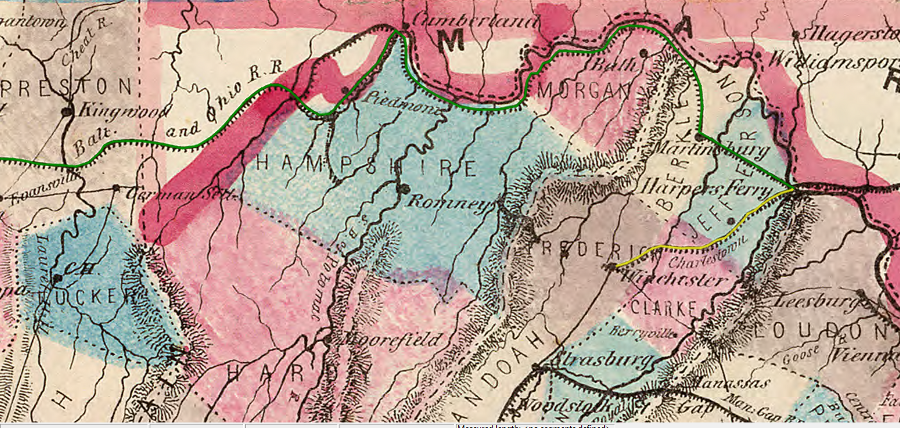

Carlile did include an odd-shaped panhandle of Shenandoah Valley counties, to ensure the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) would be located within the new state. If the war ended with a Union victory, Virginia politicians might still try to interfere with trade going to Baltimore via the B&O rather than a Virginia port, but the power of Richmond would be constrained if the entire railroad corridor was in a separate state.9

area proposed for new state on August 8, 1861 by John S. Carlile, at the start of the Second Wheeling Convention (Adjourned Session)

Map Source: Library of Congress, Map of Virginia: showing the distribution of its slave population from the census of 1860 (June 1861)

Carlile predicted that eastern Tennessee counties would also establish a separate state, rather than wait for Federal armies to win a military victory, end the rebellion of the Confederacy, and allow for the entire state to be "restored." He cited physical and economic geography as the basis for splitting Virginia, and excluding southwestern counties such as McDowell, Mercer, Monroe, and Greenbrier counties from the new state:10

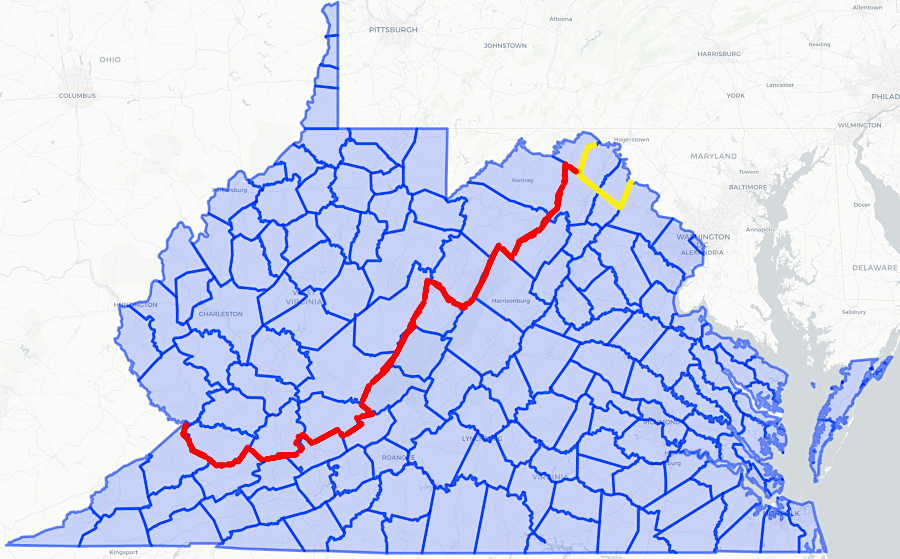

the route of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad between Harpers Ferry and Wheeling (green line) shaped the final boundaries of West Virginia, but the extension to Winchester (yellow line) had less influence and Frederick County was not added to the new state

Source: Library of Congress, New Map of Virginia: Compiled from the Latest Maps, Drawn and Colored by Hustead & Nenning (1861)

In his August 8 proposal, Carlile excluded Fairfax and Alexandria, which he suggested could become part of the District of Columbia. He did include Berkeley and Jefferson counties, despite strong support for secession there, because the new state would need to control the route of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad:

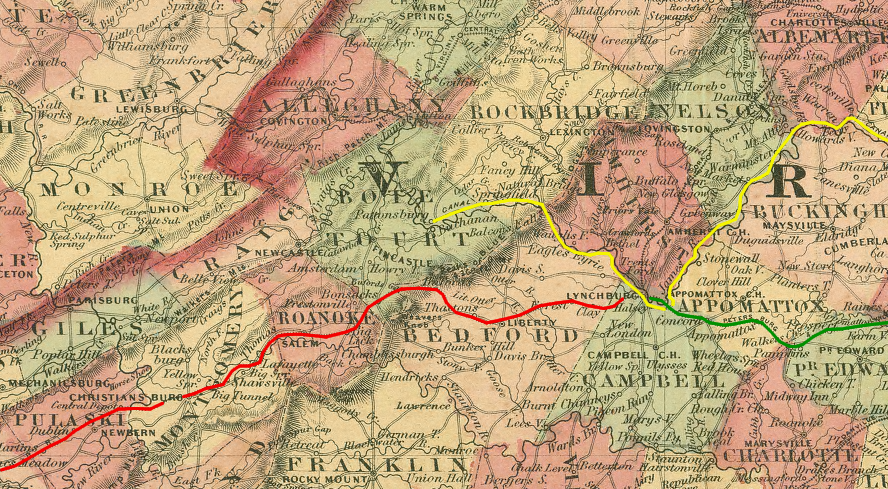

planned route of the Covington and Ohio Railroad, unfinished past Clifton Forge in 1861, extended west through Greenbrier County towards the Ohio River

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Virginia Central Rail Road showing the connection between tide water Virginia, and the Ohio River at Big Sandy, Guyandotte and Point Pleasant; made by W. Vaisz Top. Eng. (1852)

Eight days later on August 16, Carlile highlighted how the Virginia Central Railroad and the James River and Kanawha Canal links between southwestern counties and Tidewater Virginia disqualified the Trans-Allegheny Southwest District and nearby counties from joining the northwestern counties in the new state. In 1861, those transportation connections were still unfinished. The James River and Kanawha Canal stopped at Buchanan and the Covington and Ohio Railroad trains ran only to Clifton Forge, though the railroad bed was partially constructed through Greenbrier County and as far west as Charleston. According to Carlile, their influence still made the southwestern counties unsuitable for inclusion within the new state.11

In contrast to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the new state could never gain control over the endpoint of the Virginia Central Railroad and the James River and Kanawha Canal at Richmond:12

economic and cultural ties based on transportation links to Richmond, including the James River and Kanawha Canal (yellow) and the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad between Bristol-Lynchburg (red), with the South Side Railroad (green) connecting to Richmond, made northwestern Virginia politicians reluctant to include southwestern counties in the new state

Source: Library of Congress, Johnson's Virginia, Delaware, Maryland & West Virginia (1864)

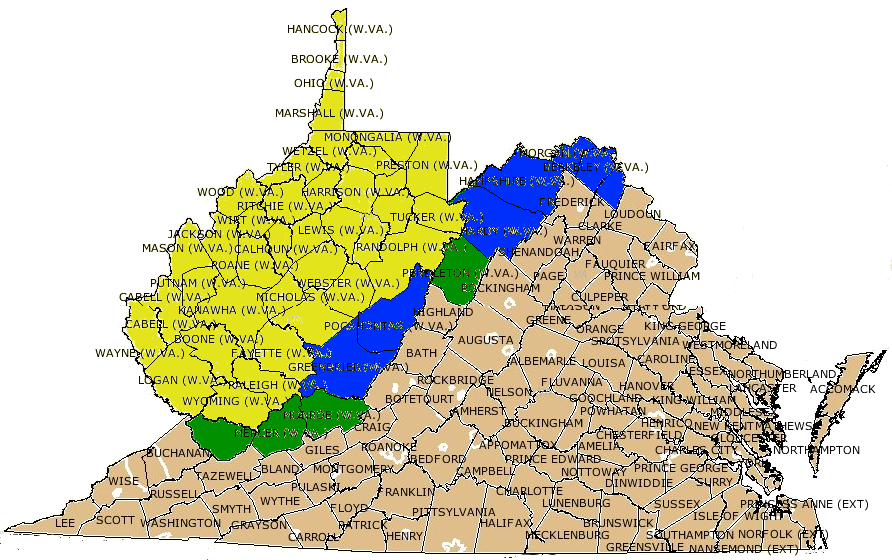

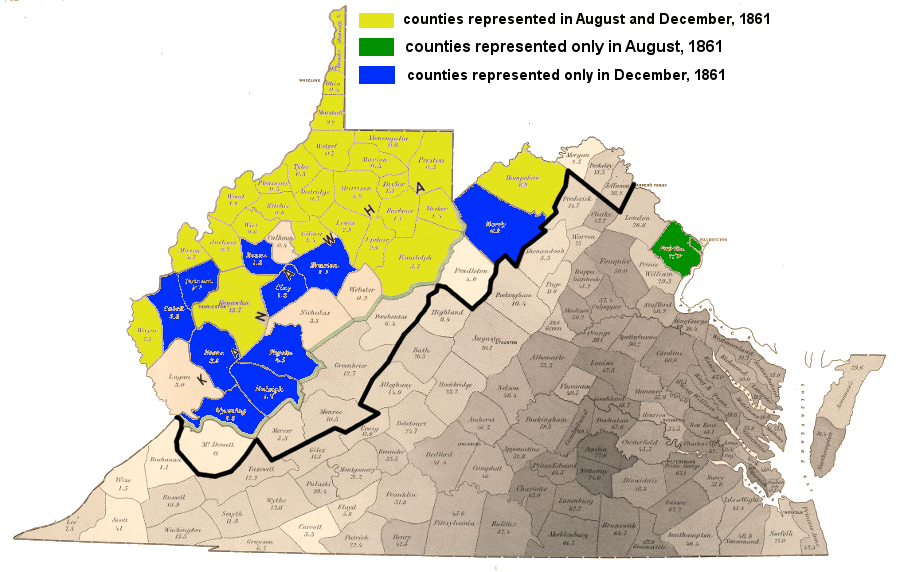

In the debate regarding the Dismemberment Ordinance between August 13-20, a core of 39 pro-Union northwestern counties near the Ohio River and the downstream part of the Kanawha River were included in all serious proposals for a new state. Logan, Wyoming, Raleigh, Fayette, Nicholas, Webster, Randolph, Tucker, Preston, Monongalia, Marion, Taylor, Barbour, Upshur, Harrison, Lewis, Braxton, Clay, Kanawha, Boone, Wayne, Cabell, Putnam, Mason, Jackson, Roane, Calhoun, Wirt, Gilmer, Ritchie, Wood, Pleasants, Tyler, Doddridge, Wetzel, Marshall, Ohio, Brooke and Hancock counties were clearly going to become part of the new state, though some of those counties failed to send representatives to the conventions or vote on the proposed state constitution in 1862.13

Left unclear was which other counties would be peeled away from the old, eastern Virginia and added to the new state. Those advocating inclusion of more "old Virginia" counties in the new state often were motivated by fear that a small new state, dominated by Republican Unionists from the northwestern counties, would end up imposing restrictions on slavery.

Supporters of slavery tried to block creation of a small new state by proposing inclusion of counties in the Shenandoah Valley with many slaveowners who supported the Confederacy. If the first proposal of the Committee on a Division of the State had been adopted, many southern/slavery sympathizers would have been included in West Virginia and the pro-Union faction in the western counties would not have obtained clear control of the new state:14

initial proposal of Committee on a Division of the State used ridgetops as well as county boundaries (splitting Scott, Giles, and Allegheny counties), and proposed Fairfax County be added to the new state

Map Source: Library of Congress, Map of Virginia: showing the distribution of its slave population from the census of 1860 (June, 1861)

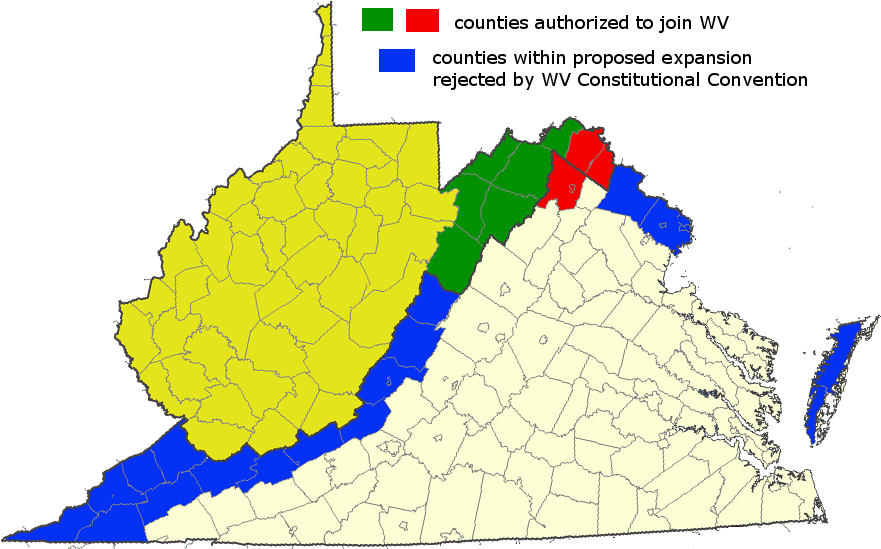

The final Dismemberment Ordinance was a compromise allowing local option decisions. The new state would include the core 39 northwestern counties, but boundaries could be expanded to include seven others (Greenbrier, Pocahontas, Hardy, Hampshire, Morgan, Berkeley and Jefferson) if residents later voted for inclusion. In addition, any county adjacent to those seven could also join.15

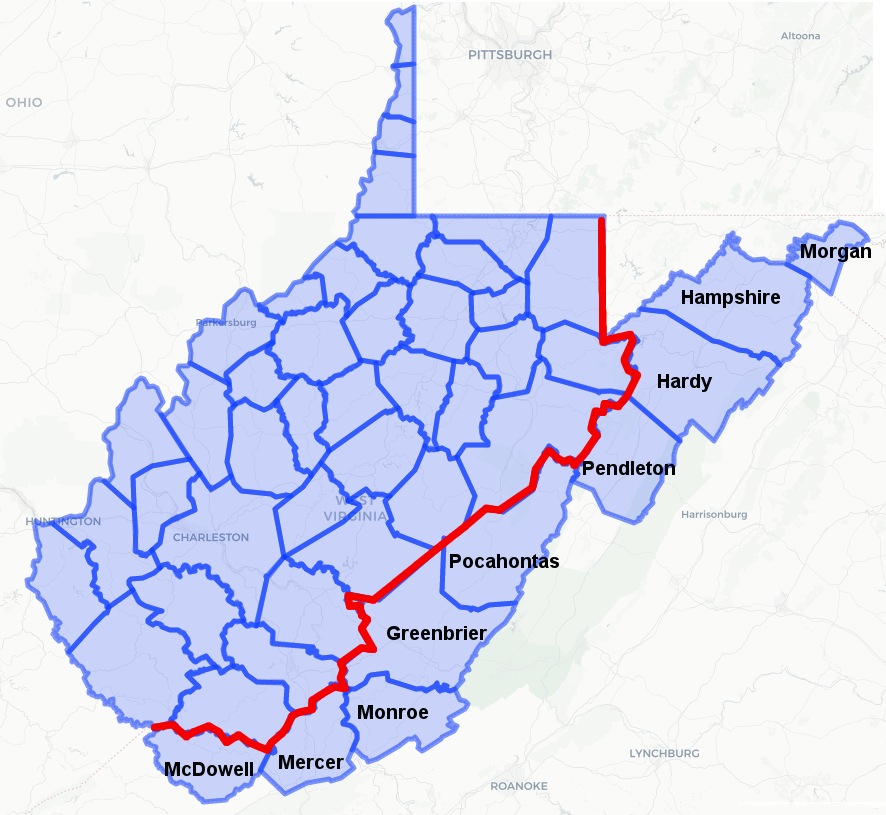

the Dismemberment or Wheeling Ordinance adopted on August 20, 1861 proposed a new state composed of 39 counties (yellow), specifically authorized Pocahontas and Greenbrier counties south of Pendleton County and Hampshire, Hardy, Morgan, Berkeley, and Jefferson on the north to opt-in to the new state (blue), and also allowed adjacent counties to join (those which finally did are shown in green)

Map Source: Newberry Library, Virginia Historical Counties

Outside of the first proposal of the Committee on a Division of the State on August 20, 1861, most lines proposed for the new state's boundaries were based on existing county boundaries rather than on topographic features. The Allegheny Front (defining the western edge of the Valley and Ridge physiographic province) was often ignored in favor of county boundaries further to the east. Since county boundaries often were based on watershed divides, however, political geography already matched physical geography closely.

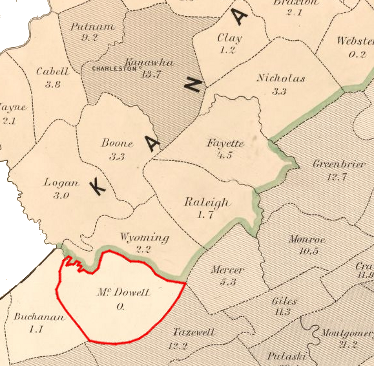

In the August 20 Dismemberment Ordinance, several counties west of the edge of the Appalachian (Allegheny) Plateau were not included in the new state, perhaps in part because the Confederate army still controlled the region at that time. For example, all-white McDowell County (where the 1860 Census recorded every one of the 1,535 of 1,535 residents as "white") was excluded by the Dismemberment Ordinance. The counties in the headwaters of the Kanawha River's tributaries ended up in West Virginia only after the Confederate military forces were expelled.16

The "Adjourned Session" of the Second Wheeling Convention proposed a new state, and called for yet another meeting to draft the new constitution. On October 24, 1861, voters in the core 39 counties - plus Hardy and Hampshire county - approved the proposal to call a constitutional convention. Fairfax and Alexandria counties did not vote on the proposed constitution, but their potential for joining the new state remained a hypothetical possibility for another year until the US Senate concluded its debate over creating the new state.17

in the October 1861 Constitutional Convention, 13 counties that ended up in West Virginia were not represented

Map Source: Library of Congress, Map of Virginia: showing the distribution of its slave population from the census of 1860 (June, 1861)

By the time the Constitutional Convention first assembled in December 1861, the Union Army had seized control of the Kanawha River valley and more counties were represented. The convention created a Committee on Boundary, which re-debated the "what counties should be included in the new state" issue at length and recycled arguments made in August during the Second Wheeling Convention ("Adjourned Session").

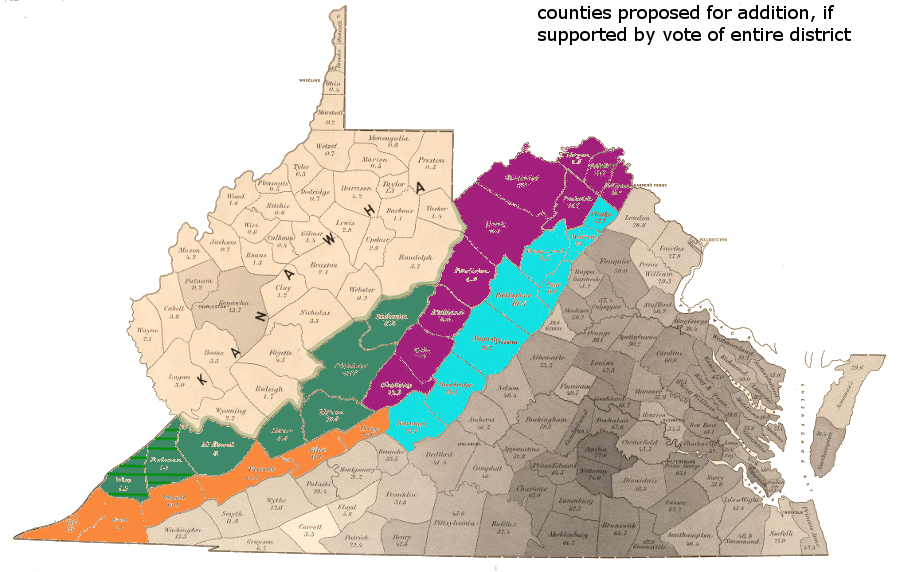

Multiple possibilities were proposed to expand beyond the 39 core counties, including adding 32 more organized into four districts:18

- Pocahontas, Greenbrier, Monroe, Mercer, McDowell, Buchanan and Wise (with one option excluding Buchanan and Wise from the district)

- Craig, Giles, Bland, Tazewell, Russell, Lee and Scott (if all voters within the district of combined counties supported inclusion)

- Jefferson, Berkeley, Frederick, Morgan, Hampshire, Hardy, Pendleton, Highland, Bath and Allegheny (if all voters within the district of combined counties supported inclusion)

- Clark, Warren, Shenandoah, Page, Rockingham, Augusta, Rockbridge and Botetourt (if all voters within the district of combined counties supported inclusion)

at one point, the December 1861 Constitutional Convention offered delegates a chance to add 32 additional counties in four separate districts

Map Source: Library of Congress, Map of Virginia: showing the distribution of its slave population from the census of 1860 (June 1861)

During debate at the Constitutional Convention, Pocahontas, Greenbrier, Monroe, Mercer, and McDowell were accepted. A proposal to include Buchanan and Wise counties clarified if topographic or political boundaries should define the edge of the new state.

One opponent claimed that a "natural and proper boundary" could be drawn based on the mountain ranges, but adding those two counties would create another panhandle (comparable to the odd shape along the western Pennsylvania border), and would be "mere excresence" on the southeastern edge of the state. Advocates for inclusion described Buchanan and Wise residents as "mountain people, without slave population," and West Virginia needed the additional population in order to qualify for a third representative in the US Congress. Future population growth also required carving our a larger territory:19

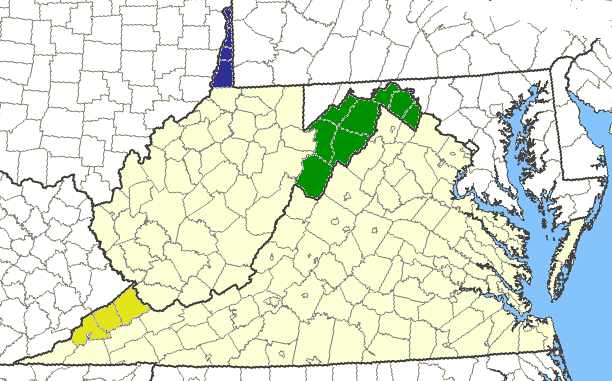

West Virginia's borders could have included a panhandle in the south, as well as at the northeastern and northwestern edges - but in the end, no counties east of the Allegheny Front were added to West Virginia except in the panhandle with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

Map Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Atlas (showing modern county boundaries)

Some highlighted how a small, compact new state would include few slaves, but proposals to enlarge the new state to include more counties to the east would add roughly five times as many slaves. Less than 3% of the population in the 39 northwestern counties were black, a smaller percentage than in Union states of Delaware (19%) or Maryland (25%). Drawing wider boundary lines to include 48,000 blacks (nearly 90% of them enslaved) would alter the character of the new state - and threaten its acceptance by the US Congress.

Other speakers noted that adding counties where Virginia had spent money to build railroads and canals, like Alleghany, would result in the new state assuming obligation for the debt. Such financial concerns blocked further consideration of the counties in the Valley District south of Alleghany, but the counties north of Alleghany were still considered valuable because of their proximity to the Baltimore and Ohio railroad.20

Because slave-free McDowell County was excluded from the proposed new state, the claim that western Virginia leaders drew their new boundary based solely on slavery is not accurate. The leaders considered the potential burden of pre-existing debt, local support from splitting off from Virginia, and the defensibility of the border against invasion as well as local opposition to slavery.

Virginia counties in 1860

Source: Library of Congress, The new naval and military map of the United States (by John Calvin Smith, 1862)

Until 1850, most new states had been added to the Union in a pattern that matched new slave and free states. Paired admissions maintained the balance of power between North and South in the US Senate. The Compromise of 1850 broke that pattern and allowed California to enter with no slave state equivalent; the Fugitive Slave Act was adopted instead to satisfy Southern states.

Ten more years of political negotiations failed to resolve the sectional split, and the southern states seceded from the Union after the new Republican Party was able to elect a president in 1860. Under President Lincoln, the Civil War was described initially as a fight to preserve the union. Confederate states focused on state's rights, but it was clear from the beginning that the key right the southern states sought to maintain was the right to maintain the institution of slavery.

Eliminating slavery was not made an official objective of the war until President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in September, 1862, but the Republican Party was the party of free-soil advocates. Adding West Virginia to the Union forced the Congress to assess whether the new state would support slavery, or be a free-soil state. The boundaries of West Virginia, and the number of slaveowners within the new state, would define the new state's character.

In late 1861, those seeking to carve out a new state from western Virginia knew that a Republican-dominated US Congress was unlikely to allow admission of another slave state. Two senators and up to three Representatives who might support the "peculiar institution" would not help the Republicans maintain political control over the Congress.

Limiting the new state to the 39 northwestern counties would limit the number of slaveowners and smooth the admission process. A new state with a minimal number of slaves might be admitted without requiring a commitment for total abolition.

On the other hand, drawing boundaries that included the counties in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province, nearly all of which had at least 10% slaves in their population, would reduce the desire of the US Congress to accept that the division of Virginia by the Restored Government in Wheeling was legitimate, and then admit the West Virginia.21

100% white McDowell County was initially excluded in boundaries proposed by the Dismemberment Ordinance on August 20, 1861

Map Source: Library of Congress, Map of Virginia: showing the distribution of its slave population from the census of 1860 (June, 1861)

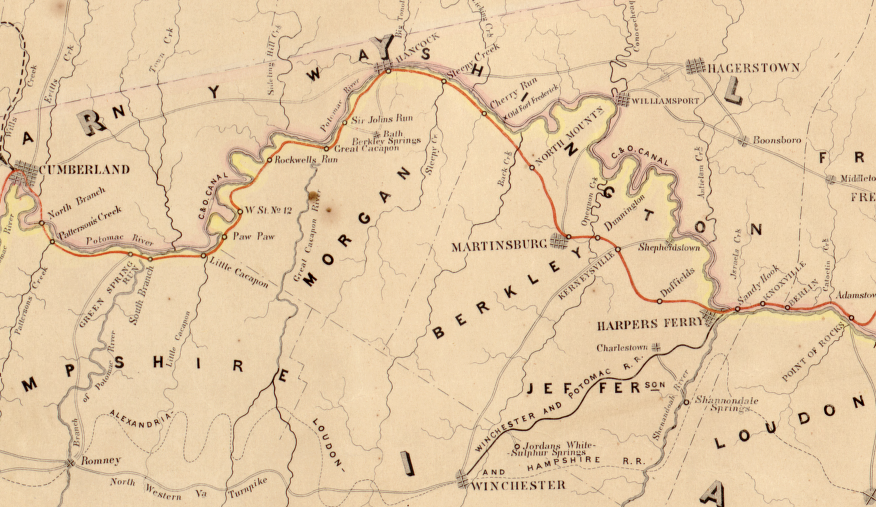

Members of West Virginia's Constitutional Convention debated the state's boundaries in detail on February 11 and 12, 1862. All of the counties in the Trans-Allegheny District (Southwest and Northwest) were included, including Pocahontas, Greenbrier, Monroe, Mercer, and McDowell. Pendleton County, which had been excluded in the Dismemberment Ordinance the previous August, was included.

Much confusion concerned how to define the northeastern corner of the state. In the end, the convention agreed to create a district of Pendleton, Hardy, Hampshire, and Morgan counties, and if the majority of voters within that district chose to join, all four counties would be added.

A second district composed of Berkeley, Jefferson and Frederick counties could also join, if a majority of voters within that district voted to become part of West Virginia. The use of districts ensured that the new state boundaries would be contiguous.22

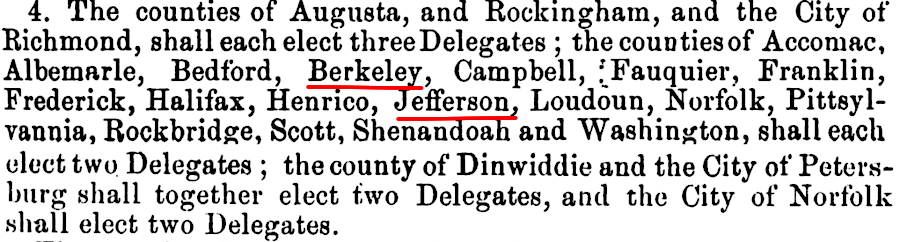

The Constitutional Convention's final approval of the boundaries required defeating one last effort to create an unviable, large state. That proposal would have included 17 more Virginia counties stretching from Lee County in the far southwest to Loudoun, Fairfax, Alexandria counties in the north - and even the two Eastern Shore counties of Accomack and Northampton.23

the 1861-62 Constitutional Convention determined that seven Shenandoah Valley counties could vote (in two districts) to join the new state, but rejected a last-minute proposal to dramatically expand West Virginia to include even the Eastern Shore

Map Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Atlas (showing modern county boundaries)

When the voters ratified the new constitution on April 3, 1862, the vote from Pendleton, Hardy, Hampshire was 465 in favor, 3 opposed. No vote returns were reported from Morgan. A majority of those voting in that four-county district was clearly in favor of joining the new state, though the total vote was low and fairness of the voting process was highly questionable.24

No vote returns were reported from the Berkeley, Jefferson, and Frederick county district. The election occurred after Stonewall Jackson had attacked Hancock (Maryland) and Romney in Hampshire County in January 1862, and his Valley Campaign started with the Battle of Kernstown on March 23. Though the Union Army occupied the Shenandoah Valley south to Strasburg and Stonewall Jackson was camped at Mount Jackson on April 3, county rather than military officials were responsible for elections.25

in 1862, it was not clear that Hardy, Hampshire, Morgan,, Berkeley, and Jefferson counties would end up in West Virginia

Map Source: Library of Congress, Colton's rail-road and military map of the United States, Mexico, the West Indies, &c. (1862)

In the lower Shenandoah Valley, few county officials openly supported dividing Virginia. For similar military and political reasons, no votes were reported from Fayette, Greenbrier, Mercer, Monroe, Morgan, McDowell, or Pocahontas counties either. The battles of Princeton in Mercer County, and Lewisburg in Greenbrier County, occurred in May 1862.

Simply voting for a new West Virginia constitution did not split Virginia and automatically make West Virginia into a new state. The US Congress had to concur.

By 1862, there were numerous precedents of Congress rejecting or adding break-away areas as new states. Under the Articles of Confederation in the mid-1780's, North Carolina blocked the proposed State of Franklin from being recognized by the Congress.

The new US Constitution clearly established a process for creating new states. Under the Constitution ratified in 1788, only Congress had the power to organize the land claims ceded by Virginia and other states to form the Northwest and Southwest territories into new states. Congress also required the formal consent of an existing state before it could be divided.

The region along the Connecticut River known as the New Hampshire Grants was admitted to the Union as the State of Vermont in 1791 only after New York concurred. Kentucky was admitted to the Union with endorsement by Virginia in 1792.

Ohio's admission in 1803 started the process of creating new states from the western land claims ceded by the original colonies to the national government under the Articles of Confederation. In 1820, Massachusetts concurred with the creation of the new state of Maine.

The 1841-42 Dorr Rebellion in Rhode Island set the precedent that the Congress itself would determine the legitimacy of a state's government, and the Supreme Court would not be involved. The court did retain authority for resolving conflicts between states, including disputes over state boundaries.

After the start of the Civil War, leaders in the western counties understood that the state of Virginia would have to authorize the creation of any new state from within Virginia's boundaries. Article IV, Section III of the Constitution says:26

The Confederate state government based in Richmond would never concur with a division. However, the Restored Government of Virginia based in Wheeling claimed to represent the entire state. The Virginia legislature and Governor Pierpont in Wheeling authorized the creation of West Virginia on May 13, 1862. That occurred as General McClellan marched the Union Army up the Peninsula and "on to Richmond," and four days after the CSS Virginia and USS Monitor fought the first battle of ironclad ships in Hampton Roads.

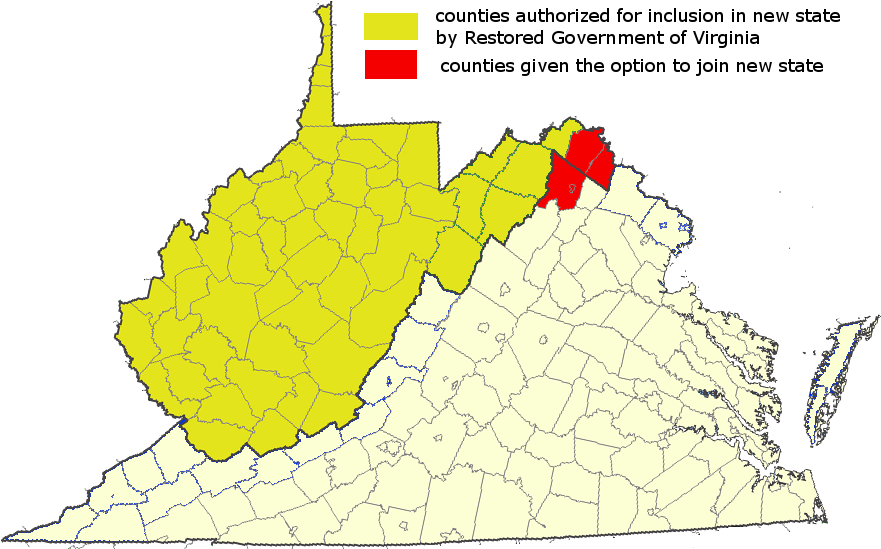

In the May 13, 1862, authorization, the Restored Government of Virginia dropped the new state constitution's requirement for Pendleton, Hardy, Hampshire and Morgan to opt in, even though Morgan had submitted no returns for the April 3 ratification vote. NOTE: Since that time, Hardy and Hampshire have divided to form the new counties of Grant and Mineral.27

The Restored Government of Virginia also dropped the requirement for Frederick, Jefferson, and Berkeley to be added as a single district, allowing them to join individually:28

the Restored Government of Virginia authorized creation of a new state that included Morgan, Hampshire, Hardy, and Pendleton, with the option for Frederick, Jefferson, and Berkeley to join

Map Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Atlas (showing modern county boundaries)

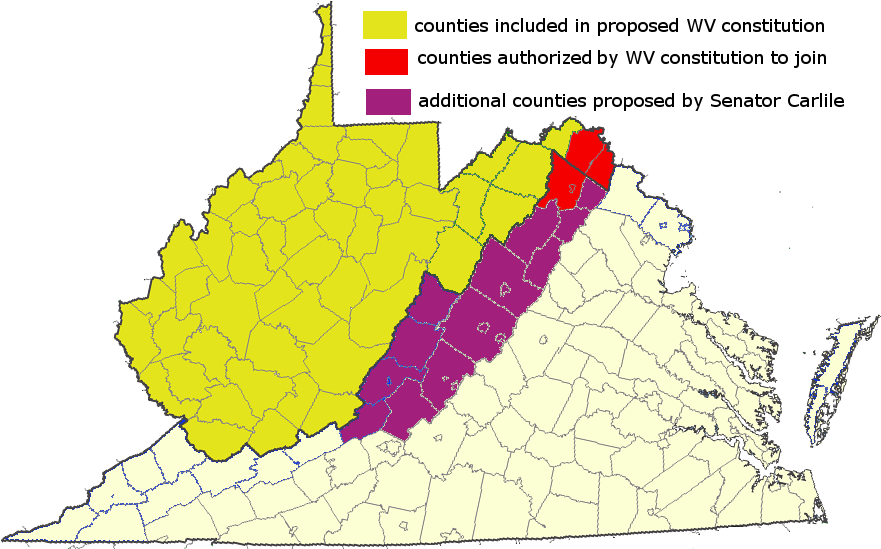

In the US Congress, Senator John Carlile (representing the Restored Government of Virginia) wrote the initial bill to admit West Virginia. To the surprise of many, he proposed expanding the boundaries to include 12 additional Virginia counties beyond Berkeley, Jefferson, and Frederick. Carlile added Clark, Warren, Page, Shenandoah, Rockingham, Augusta, Highland, Bath, Rockbridge, Botetourt, Craig, and Alleghany counties.29

Senator Carlile proposed adding 12 counties, beyond those included in the constitution of West Virginia

Map Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Atlas (showing modern county boundaries)

Carlile had been a long-time advocate for splitting Virginia, but he was not an abolitionist. Once it became clear that Republicans in Congress would require limits on slavery, he sought to block creation of a new state.

He may have been trying to sabotage admission of West Virginia in hopes that a Union military victory would allow "old Virginia" to rejoin the Union as one intact state, without emancipation of existing slaves.30

Abolition of slavery was not popular in western Virginia. Politicians pushing for the new state wanted to free the west from domination by the Tidewater/Piedmont, not to free the slaves held in the west. The proposed West Virginia constitution allowed slavery to continue. New slaves and free people of color would be prohibited from entering the new state, but slaveowners could maintain their existing "property." Under the constitution, new slave children born in West Virginia would remain slaves, perpetuating the institution forever.

Congress ended up requiring West Virginia to modify the constitution; a form of abolition was the price for joining the Union. The other US Senator from Restored Virginia, Waitman T. Willey, sponsored the amendment to the act of admission that obtained final support from the US Congress, the reconvened Constitutional Convention, and finally the voters of West Virginia:31

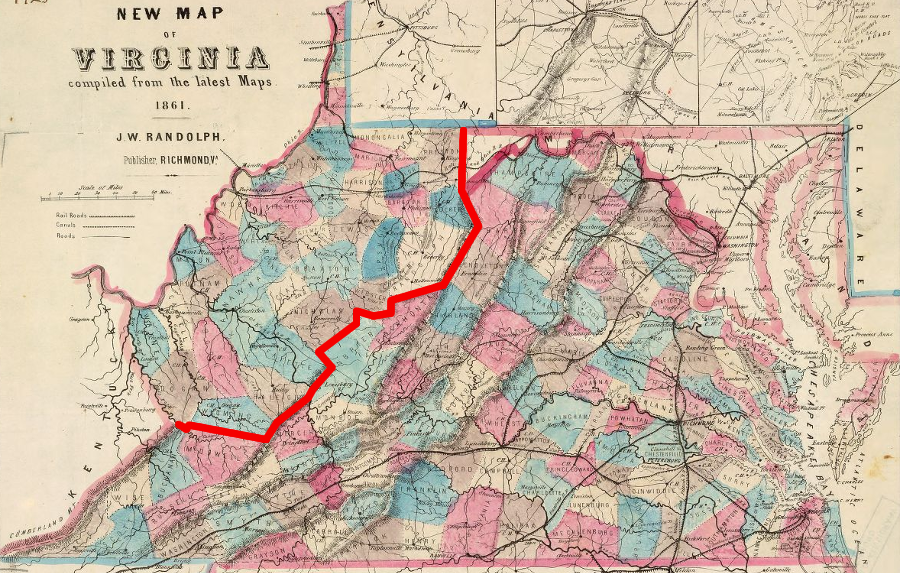

In June, 1862, Congress required President Abraham Lincoln to define "insurrectionary districts" where extra taxes would be imposed. Lincoln classified the majority of Virginia to be an insurrectionary district, but excluded the 39 northwestern Virginia counties. He identified as "insurrectionary" nine counties (Morgan, Hampshire, Hardy, Pendleton, Pocahontas, Greenbrier, Monroe, Mercer, and McDowell) that ultimately were included within West Virginia in 1863. In addition, Berkeley and Jefferson counties were also considered to be "insurrectionary."32

President Lincoln excluded 39 counties in western Virginia when he defined "insurrectionary districts" on July 1, 1862

Source: Library of Congress, New map of Virginia: compiled from the latest maps (by J.W. Randolph, 1861)

in 1862, President Lincoln considered nine counties in what became West Virginia a year later to be "insurrectionary districts"

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries - West Virginia

Abraham Lincoln signed the bill to admit West Virginia on December 31, 1862. The admission was conditional, requiring acceptance of the Willey Amendment. The reconstituted Constitutional Convention approved the revision on February 17, 1863 and West Virginia voters concurred on March 26.

That meant the executive, legislature, and judicial officials of the Restored Government of Virginia would have to leave Wheeling, and new West Virginia officials would have to be elected before the new state became official on June 20, 1863. Governor Francis Pierpont and the Restored Government of Virginia moved to Alexandria, which Union troops had occupied since the start of the Civil War. A special convention in Alexandria proclaimed a new state constitution in April, 1864 that included Berkeley and Jefferson counties within election districts for House of Delegates and State Senate seats.33

the 1864 constitution included Berkeley and Jefferson counties in Virginia election districts

Source: Hathi Trust, Constitution of the State of Virginia, and the ordinances adopted by the Convention which assembled at Alexandria, on the 13th day of February, 1864

The election for a new West Virginia governor and other officials for the new state was held on May 28, 1863. Voters in Berkeley and Jefferson counties voted at the same time to join West Virginia.

In preparation for such a vote, the legislature of the Restored Government of Virginia had passed a law on January 31, 1863 authorizing Berkeley county voters to chose to become part of West Virginia, and stating in advance that the Restored Government of Virginia concurred in the decision if the county asked to be annexed to West Virginia.

A similar bill on February 4 authorized votes in Jefferson and Frederick counties for annexation to the new state. The February 4 law also echoed the final debate a year earlier in the 1862 Constitutional Convention, and authorized additional votes to determine annexation preferences in various districts composed of Tazewell/Bland/Giles/Craig counties, Buchanan/Wise/Russell/Scott/Lee counties, Alleghany/Bath/Highland counties, Clarke/Loudoun/Fairfax/Alexandria/Prince William counties, and Shenandoah/Warren/Page/Rockingham counties.34

the Restored Government of Virginia legislature authorized several districts to vote for annexation to the new state on May 28, 1863, at the same time elections were held for new State of West Virginia officials

Map Source: Newberry Library, Virginia Historical Counties

On May 28, 1863, voting was conducted only in Jefferson and Berkeley counties. An earlier January 5, 1863 effort to elect a US Representative from the 8th District of Restored Virginia demonstrated the difficulty of holding elections in the middle of the Civil War. Morgan County voted, and there were partial vote returns from Hampshire and Berkeley counties, but no votes were reported from Frederick, Page, Warren, Loudoun, Clarke, or Jefferson counties. The US Congress refused to seat the person claiming to represent the district, saying the election was too irregular:35

Though the May 28, 1863 election in Berkeley and Jefferson counties included irregularities, Governor Francis Pierpont of the Restored Government of Virginia officially certified the annexation decisions to Governor Arthur Boreman of West Virginia in July. Final incorporation of the two counties was approved in separate laws passed by the legislature of West Virginia - the state was "official" after June 20, 1863. Berkeley County was added by the West Virginia legislature on August 5, 1863, and Jefferson County was added on November 2, 1863.36

Berkeley and Jefferson counties were added later to West Virginia after the decision by Congress to accept the new state, and that boundary alteration was approved by the US Supreme Court in 1870

Source: Library of Congress, County map of Virginia and West Virginia (by S. Augustus Mitchell, 1863)

In 1864, the Restored Government of Virginia adopted a new state constitution. When defining the jurisdictional boundaries of the 13th Circuit Court, the new constitution included Jefferson and Berkeley counties along with Clarke and Frederick counties. That action suggests the General Assembly of the Restored Government of Virginia was less willing than Governor Francis Pierpont to cede those two counties to West Virginia.

The 1864 constitution also declared that the debt of Virginia which existed when West Virginia was created would be shared by the two states. The controversy about how to assign a fair share of debt to each state continued until a final Supreme Court decision in 1915. West Virginia made its final payment in 1920.37

the Restored Government of Virginia included West Virginia's debt obligation in the new state constitution adopted in 1864

Source: Hathi Trust, Constitution of the State of Virginia, and the ordinances adopted by the Convention which assembled at Alexandria, on the 13th day of February, 1864

After the Civil War ended, the Restored Government of Virginia moved from Alexandria to Richmond. Governor Pierpont ended up with a legislature meeting in the State Capitol that did not share his views on the creation of West Virginia.

The first Virginia General Assembly elected in 1865 after the Confederate defeat was filled with conservative Democrats. On December 5, 1865, the Virginia legislature dominated by those conservatives repealed the 1862 law by the Restored Government of Virginia that had authorized the creation of West Virginia.

The legislature also repealed the 1863 laws authorizing the transfer of Berkeley and Jefferson counties to West Virginia. Governor Francis Pierpont was in the unusual position of being in office when the 1865 Virginia legislature repealed the 1862 legislation that he had championed while governor of the Restored Government of Virginia.

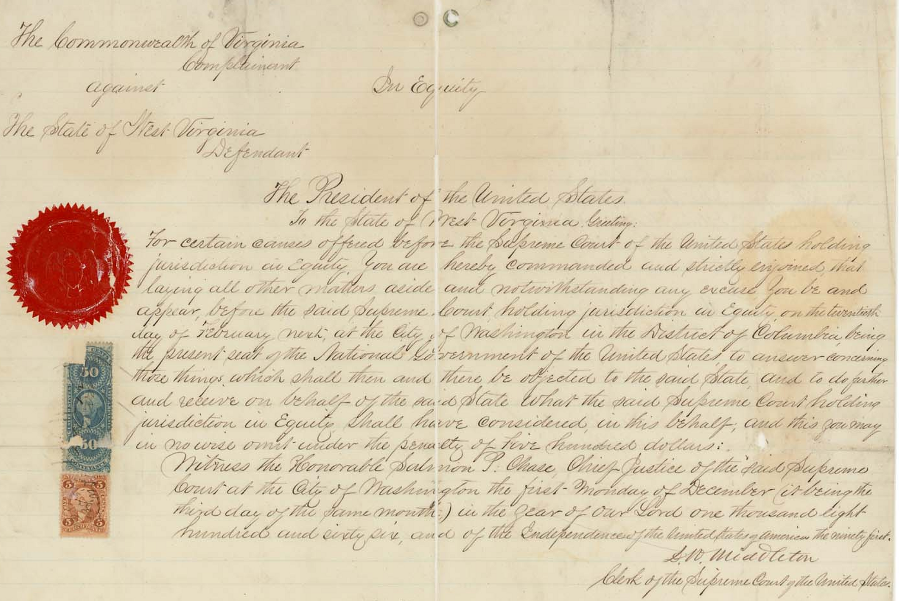

The US Congress came to the defense of West Virginia's territorial integrity. It passed the "Joint Resolution giving the consent of Congress to the transfer of the Counties of Berkeley and Jefferson to the State of West Virginia" in March, 1866. Virginia then shifted its efforts from the legislative to the judicial branch and sued West Virginia. In 1870, the Supreme Court ruled that the transfer of the two counties to West Virginia was legal.38

subpoena issued by Salmon P. Chase, Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court, after Virginia claimed it was unconstitutional to incorporate Berkeley and Jefferson counties into West Virginia

Source: National Archives Prologue, Is West Virginia Constitutional?

The shift of Berkeley and Jefferson counties to West Virginia may have violated legal as well as territorial boundaries, but after the Commonwealth of Virginia seceded in 1861 the state lost credibility for making a legal case. In 1870, Virginia's legal claim was based on a framework of Federal laws tied to the US Constitution which the state had declared no longer valid in 1861:39

West Virginia was expanded in 1866 to include Berkeley and Jefferson counties, to ensure no part of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad would be within the boundaries of Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, The theatre of war or the stage as set for the opening scenes of 1861

A number of different justifications were offered between 1861-66 for drawing the West Virginia boundary at different locations, after decades of intrastate sectional conflicts. If the official split has occurred in 1790, the boundary may have been the crest of the Blue Ridge. Had the Civil War occurred in 1850, then West Virginia may have included the southwestern counties in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province.

Once the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad was built to Bristol, and the James River and Kanawha Canal completed to Buchanan, the Blue Ridge transportation barrier was breached. The upper Tennessee River watershed in Southwest Virginia, and the James River watershed west of the Blue Ridge, were connected with Tidewater ports, and agriculture was transformed. Large landowners raised tobacco, wheat, corn and livestock for shipment to Lynchburg, Petersburg, and Richmond. A cash economy was integrated with customers and bankers in Virginia's Tidewater and Piedmont cities. As part of the cultural change, slavery became more common in the region - and Valley District counties went into debt to help finance the railroad.

West Virginia politicians struggled to justify any boundary other than the Blue Ridge, and by 1860 there were too many slave-owners in the Valley District to incorporate most of that region. Annexing Berkeley and Jefferson counties required extraordinary effort to hold elections and then defend the annexations.

Abraham Lincoln asked his Cabinet to evaluate if admitting West Virginia was 1) constitutional and 2) expedient. His six Cabinet officials split evenly on whether Virginia should be divided. Lincoln recognized that the legal processes used to create the new state and to define its boundaries were irregular, but finally decided that it was in the national interest to admit West Virginia:40

route of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

Source: Library of Congress, Map and profiles showing the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road with its branches and immediately tributary lines, 1858

Hampshire County was clearly part of West Virginia before Jefferson County, which might help resolve the question "what is the oldest town in West Virginia?" The Virginia General Assembly approved charters for both Romney and Shepherdstown on December 23, 1762. The third reading of the ordinance for the Shepherdstown charter was processed first, but no one knows which bill was signed first by Governor William Berkeley. What is known is that Hampshire County, with the town of Romney, was part of West Virginia before Jefferson County and Shepherdstown.

The delayed addition of Jefferson and Berkeley counties provided assurance to Unionists that the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad would be protected from interference by any future secessionists in Virginia, or from Tidewater-centric politicians in Richmond. Curiously, it was the West Virginia politicians that came to regret the power of the railroad. In the revision of the West Virginia constitution in 1872, railroad officials were banned from serving in the legislature, in part for fear that the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad would control the new state and bypass West Virginia while steering business directly to Ohio.41

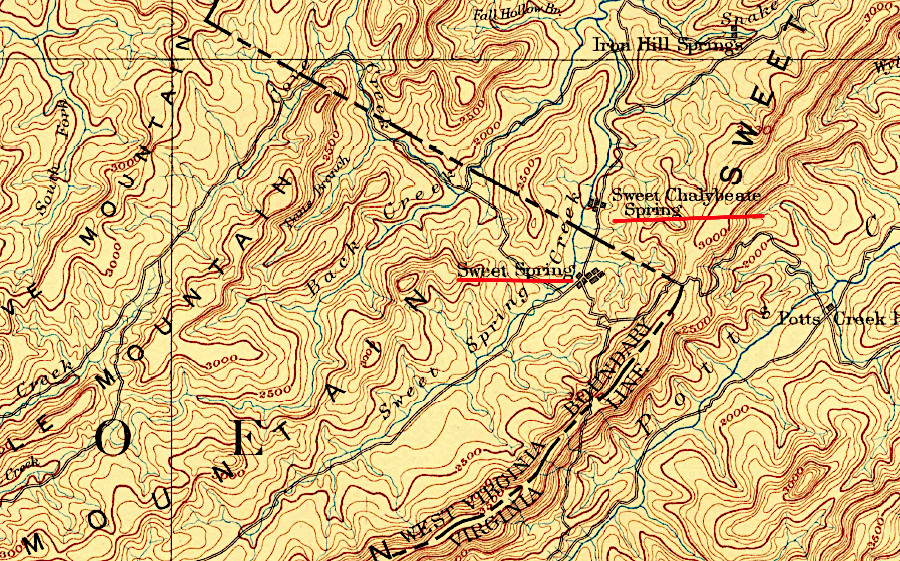

The survey of the boundary between Alleghany County, Virginia and Monroe County, West Virginia may have been affected by a rivalry between the owners of two "springs," the resorts of the late 1800's.

In 1862, John Kelly, an Irish contractor who built the Blue Ridge Tunnel and other railroad tunnels before the Civil War, purchased Sweet Chalybeate Springs in Alleghany County. Sweet Springs Resort in Monroe County, one mile away, was owned by Oliver Beirne. According to local legend, he arranged with the surveyors to mark the state boundary so the two resorts would be in separate states and he would not have to deal with John Kelly.

John Kelly got the last laugh, however. When he died in 1887, the only Catholic cemetery in the area was on the Sweet Springs property and he was buried near the resort of Oliver Beirne.42

the rivalry between the owners of two "springs" may have shaped the location of the Alleghany County-Monroe County line

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Lewisburg, VA 1:25,000 topographic quadrangle (1887)

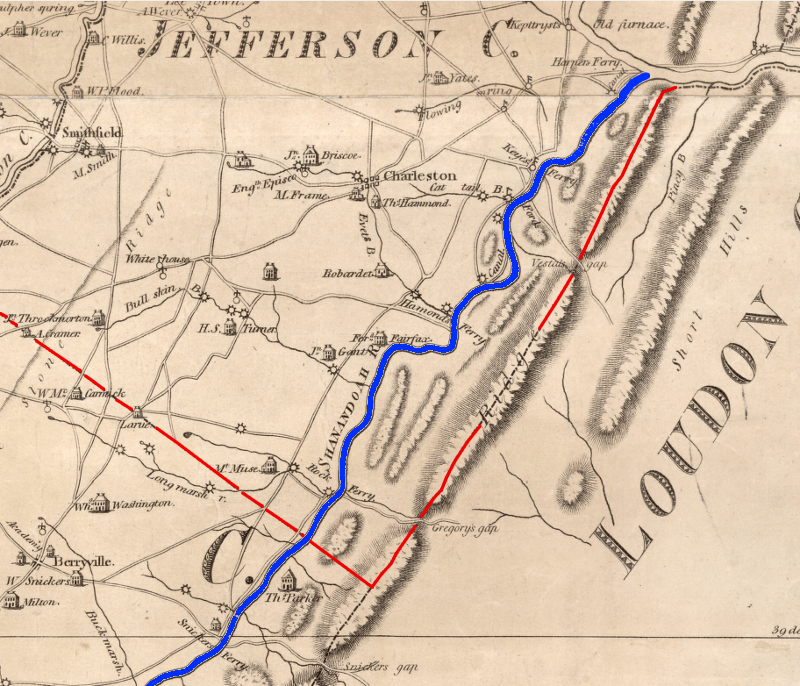

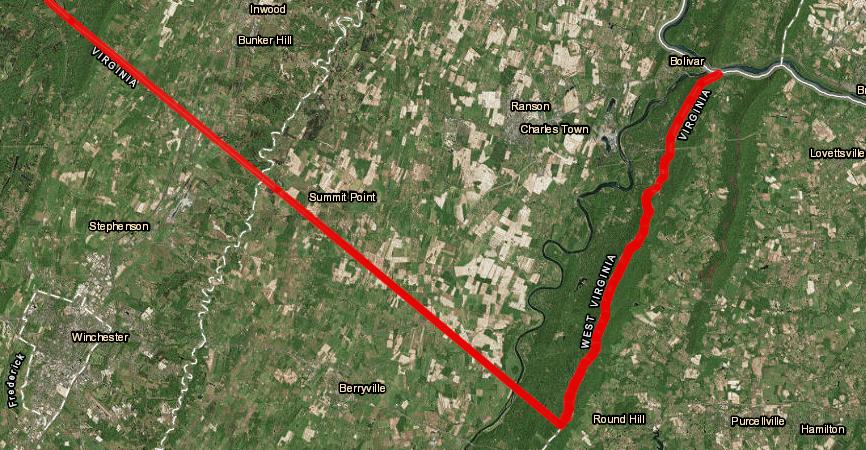

The Virginia-West Virginia boundary is still not final in some places. In 1991, the Virginia and West Virginia legislatures appropriated money for a boundary commission to look at 15 miles of fuzzy border between Loudoun County, Virginia and Jefferson County, West Virginia, after an assault prosecution was thrown out of court. Because the boundary was not clear, the Virginia Attorney General could not prove the crime took place in Virginia.

After a 1997 survey, the boundary line between Jefferson County, West Virginia, and Loudoun County, Virginia, was declared to be the watershed line of the top of the ridge of the Blue Ridge mountains, as documented in the survey. The topographic boundary was modified where Route 9 crossed the watershed divide. Previous road work had lowered the grade, and 800 feet of road traditionally maintained by Virginia were technically on the West Virginia side of the divide.43

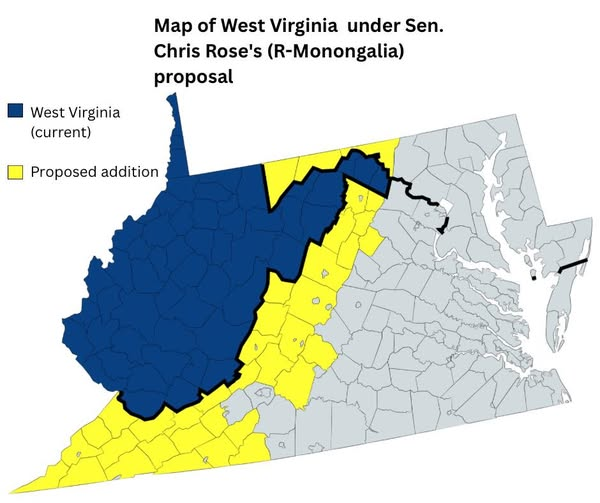

In 2020, the West Virginia Senate invited Frederick County to become part of West Virginia. The West Virginia House of Delegates then invited all Virginia counties to join West Virginia.

The legal basis for Frederick County to secede from Virginia was based on action by the legislature of the Restored Government of Virginia. It had authorized Frederick County to vote in 1863, along with Morgan and Jefferson counties, on joining the new state of West Virginia.

The resolutions were introduced when the Virginia General Assembly was considering legislation regarding guns, triggering an uproar about Second Amendment rights. Politically, almost all the counties on either side of the state line were similar. The West Virginia counties on the border had voted heavily for Donald Trump in 2016, as did all but one of the Virginia counties on the border. The outlier was Loudoun County in Northern Virginia, where Hillary Clinton won 55% of the vote in 2016.

The political basis for changing states was incorporated in the 2020 resolution in the Senate, which guaranteed that becoming part of West Virginia would help Frederick County residents protect:44

counties were invited to separate from Virginia, comparable to Britain's "Brexit" from the European Union

Source: Vexit 2020

West Virginia Governor Jim Justice and Liberty University President Jerry Falwell Jr., two Republican leaders strongly supportive of President Trump, championed the proposed adjustment in the state boundary by making literally divisive political statements. The House of Delegates resolution highlighted the cause for their support:45

Jerry Falwell Jr. stated harshly:46

In Tazewell County, supervisors passed a Second Amendment sanctuary resolution which highlighted the potential to form a militia, reflecting the local feelings about gun control laws after the 2019 elections shifted control of the General Assembly from Republicans to Democrats. One resident later encouraged his county supervisors to support "Vexit," saying:47

John Denver's song "Country Roads" starts with Almost heaven, West Virginia... Blue Ridge Mountains, Shenandoah River - but only a small portion of those geographic features are located in Jefferson County

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Frederick, Berkeley, & Jefferson counties in the state of Virginia and ESRI, ArcGIS Online

After Democrats in Virginia swept the elections in 2025 for statewide offices and the House of Delegates, a legislator in West Virginia proposed that his state should expand to incorporate 21 counties in Virginia and three in Maryland. He later added six more counties to his invitation - Amherst, Bedford, Botetourt, Floyd, Pulaski and Rockbridge.

Montgomery and Roanoke counties were excluded. No independent cities surrounded by the counties were included specifically in the resolution, even though Bristol, Buena Vista, Covington, Galax, and Norton had voted for the Republican ticket. In West Virginia, cities are not separate from counties.

The proposed boundary change was a political stunt, but it highlighted how people living in the western regions of Maryland and Virginia voted differently than the majority within the states. Democrats won statewide elections and controlled the state legislatures in Virginia and Maryland, but most voters west of the Blue Ridge were Republicans like the majority in West Virginia. The West Virginia state senator noted that the proposed additions:48

27 Virginia counties and 3 Maryland counties were invited to separate from Virginia and join West Virginia, after Democratic candidates won the 2025 elections in Virginia

Source: State Senator Chris Rose, Facebook post (November 18, 2025)

between 1863-66, it was unclear if Berkeley and Jefferson counties were part of Virginia or West Virginia

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

Source: West Virginia Public Broadcasting, West Virginia: The Road to Statehood - New

crossing the Virginia-West Virginia border on US 50 in 1940

Source: Library of Congress, State line. Virginia--West Virginia (by Arthur Rothstein, 1940)