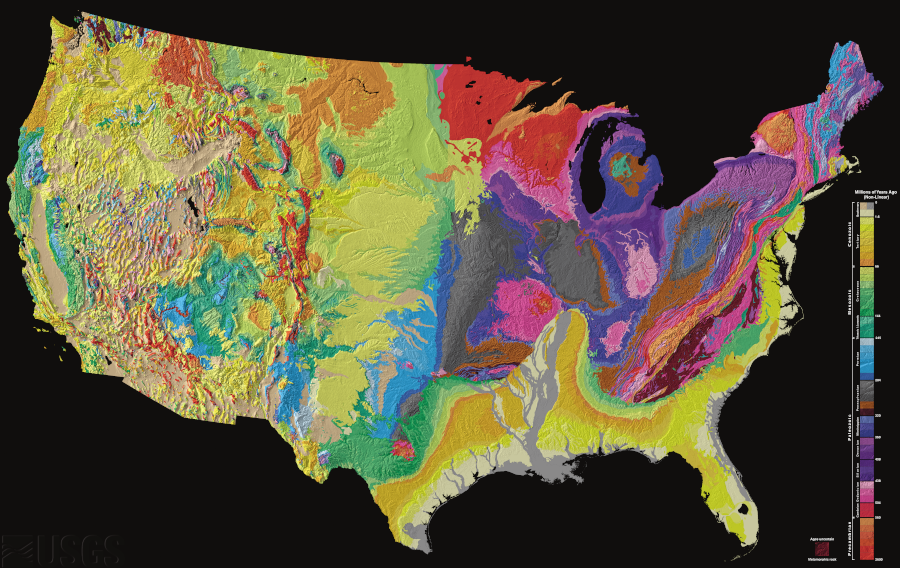

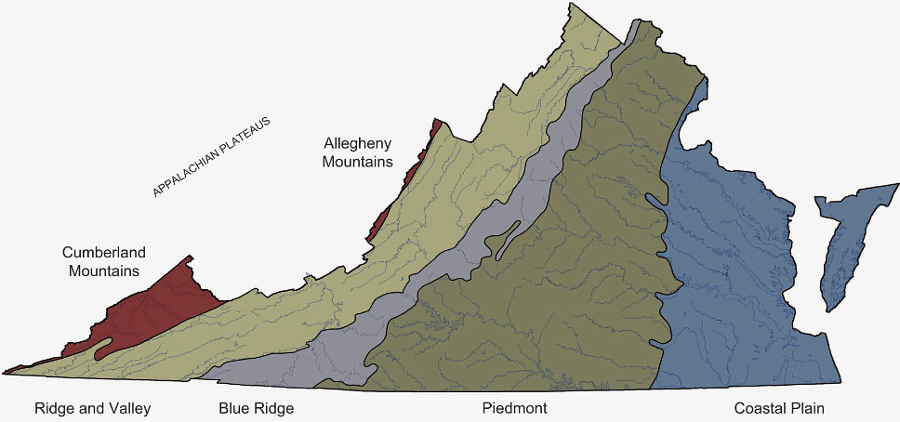

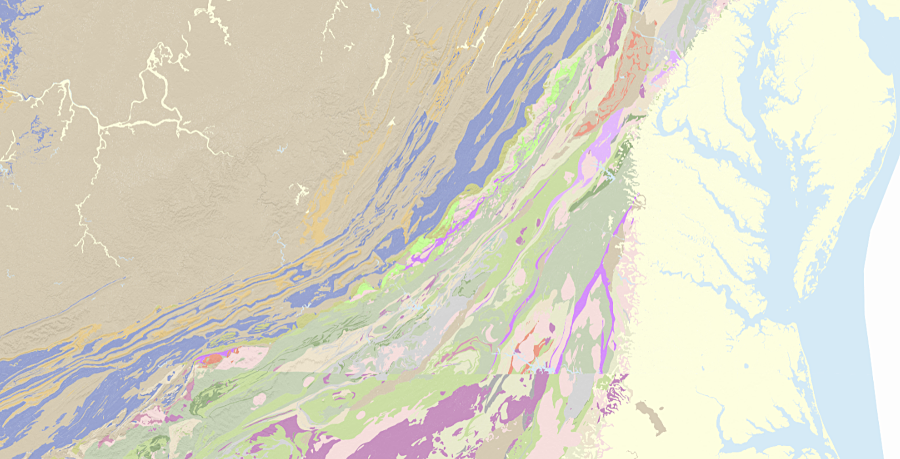

geology and topography are fundamental starting points for classifying physiographic regions

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), A Tapestry of Time and Terrain (1970)

geology and topography are fundamental starting points for classifying physiographic regions

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), A Tapestry of Time and Terrain (1970)

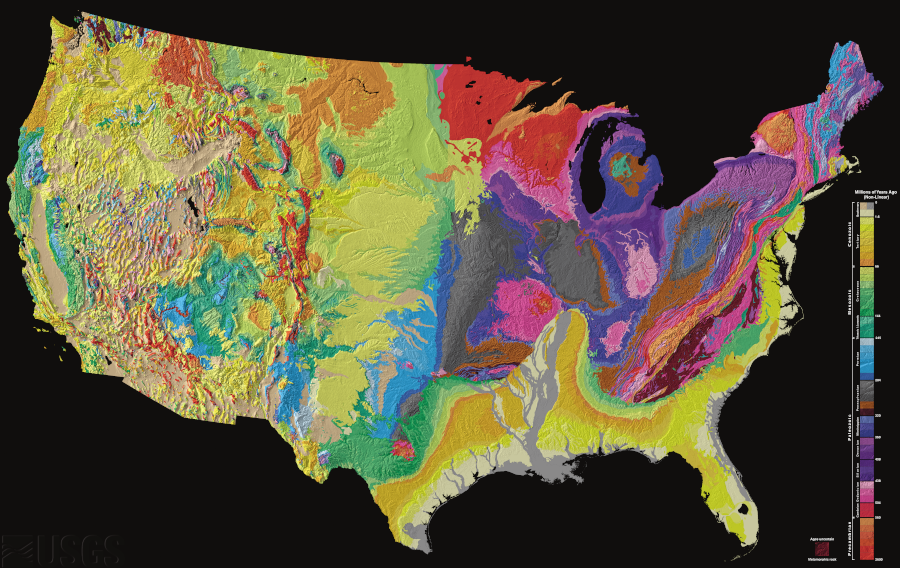

The collisions of continents, and the erosion by wind and rivers, have left impacts obvious to even the untrained eye. In 1670, the early explorer John Lederer understood that Virginia was not a homogenous place. Centuries before aerial photography and satellite imagery, Lederer recognized that every part of the colony did not look just the same. He classified the landscape by topography:1

the Flats, the Highlands, and the Mountains...

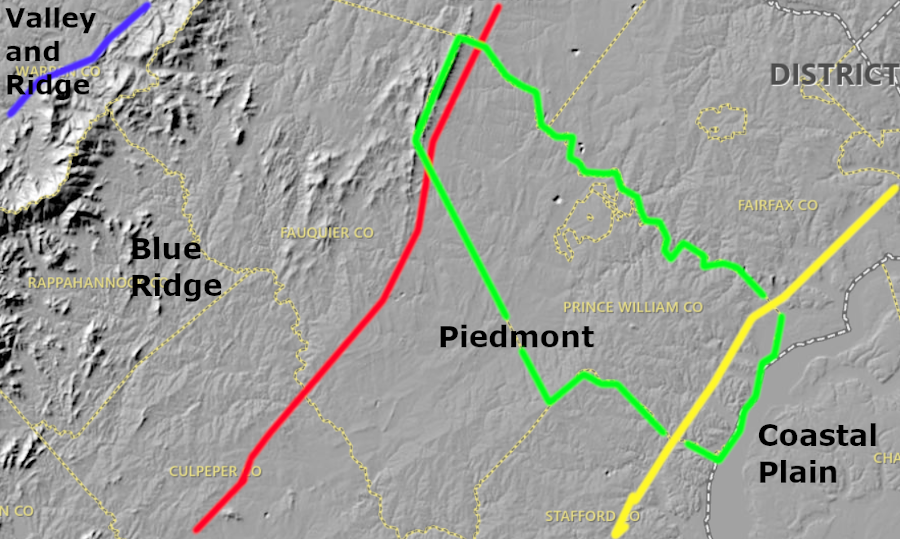

(Note how far east I drew the boundary between the Highlands and the Mountains. That location reflects the geology of the underlying bedrock.

If you were drawing the line based on just topography... you'd probably draw it further to the west.)

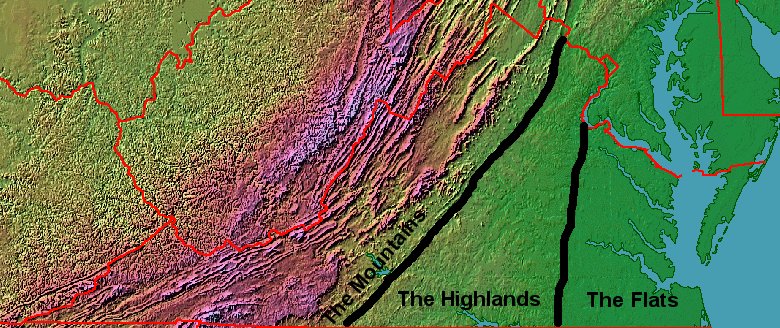

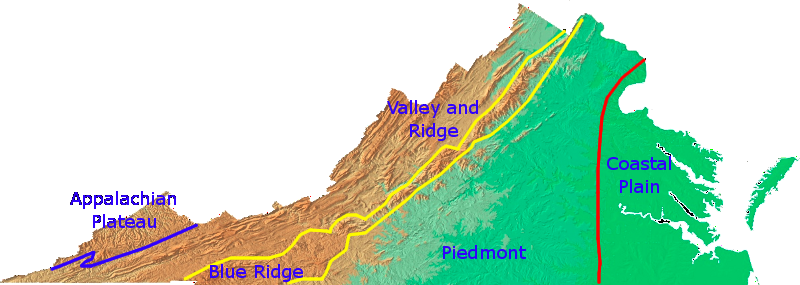

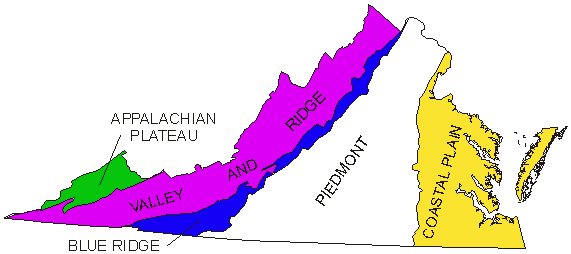

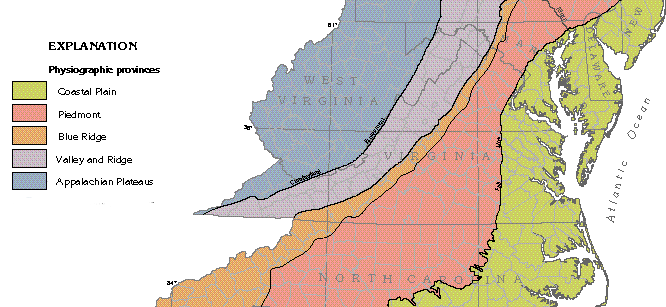

Virginia is divided into various physiographic regions defined primarily by a combination of geology (the rocks underneath the soil) and topography (hills, valleys, and flat spots). Political boundaries are well-marked in Virginia, with signs on roads identifying when you cross a boundary between counties/cities. However, it's less obvious where to draw the line between physiographic regions.

John Lederer recognized the distinct character of three physiographic provinces:

Coastal Plain sediments (yellow) were deposited across the Southeast when sea level were higher

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Heavy-Mineral Sand Resources in the Southeastern U.S.

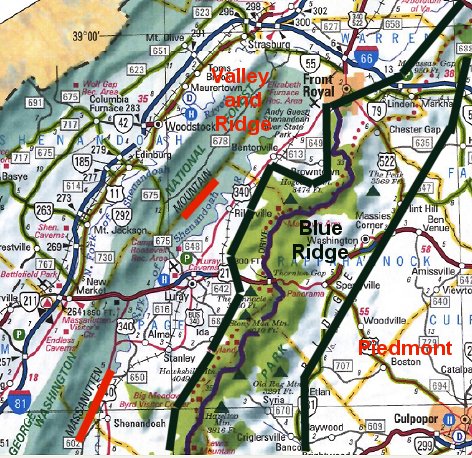

Lederer may have reached Manassas Gap, where I-66 cuts through the western limb of the Blue Ridge near Front Royal. He looked west from the Blue Ridge, and may have gone down into the Shenandoah Valley after climbing through one or more different passes or low gaps in the ridge.

Had he explored further west, he may have recognized the distinctive character of the valleys and ridges west of the Blue Ridge. They deserve their own label, the Valley and Ridge province. So does the flat highland even further west that we now call the Appalachian Plateau.

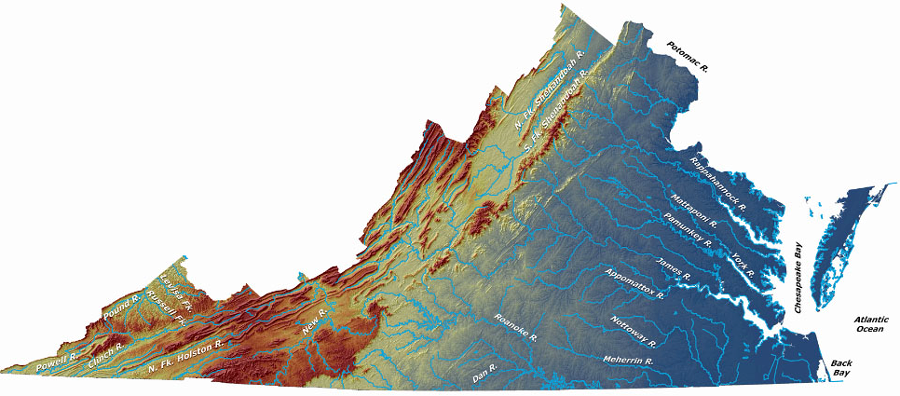

Virginia's physiographic regions, from the Coastal Plain on the east to the Appalachian Plateau on the west

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Overview of the Physiography and Vegetation of Virginia (Figure 2)

physiographic provinces of Virginia

Source: USGS Open-File Report 99-11, Color Shaded Relief Map of the Conterminous United States

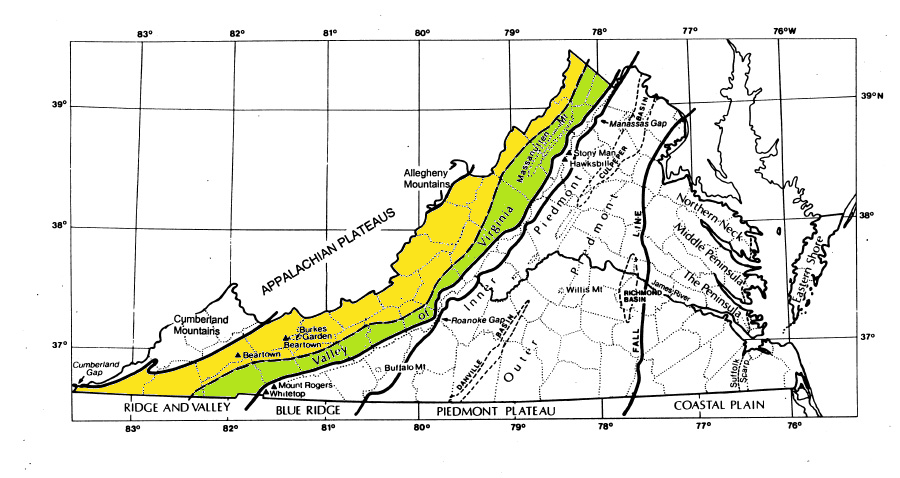

Not everyone draws the exact same physiographic boundaries for locations in Virginia area. Typically, geologic boundaries distinguised by geologic "formations," or separate types of rock that can be mapped. Formations are defined more precisely than physiographic region boundaries.

The boundaries of geologic provinces based on bedrock do not match up exactly with the edges of physiographic provinces, or with cultural regions. The Shenandoah Valley includes the watershed of the Shenandoah River, but the watershed divide separating it from the valley of the James River at Raphine/Steeles Tavern is not obvious to a driver on I-81. The city of Lexington is in the James River watershed, not in the Shenandoah Valley, but Lexington may be described as being in the Valley of Virginia.

the Valley of Virginia (colored green), where colonial settlers could walk most easily from one watershed to another, refers to the eastern edge of the Valley and Ridge physiographic province (remainder colored yellow)

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, The Natural Communities of Virginia Classification of Ecological Community Groups

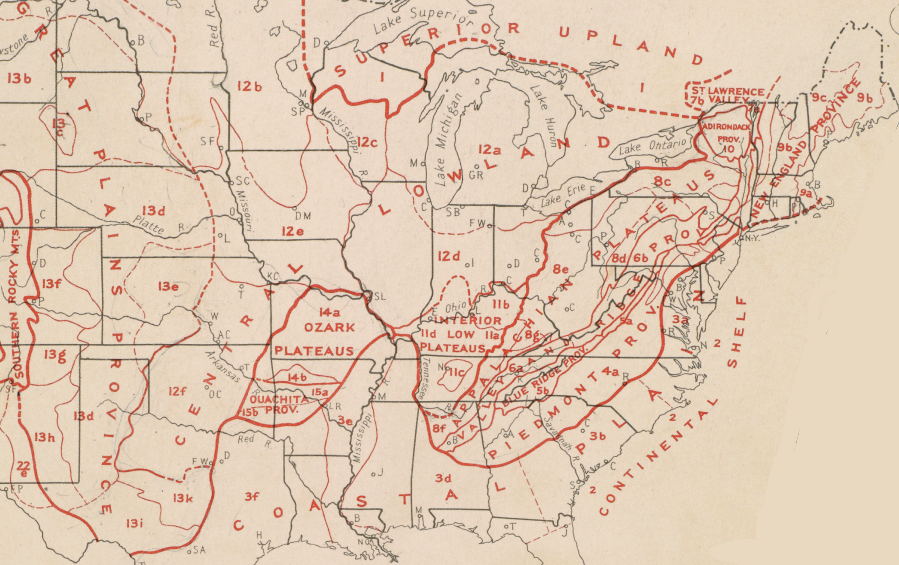

Starting in the 1720's, waves of colonial settlers walked from Philadelphia into Virginia's Valley and Ridge physiographic province. West of the Blue Ridge, land was cheap enough for new immigrants with few assets. As the Scotch-Irish and German-speaking Pennsylvania "Dutch" moved further south, the settlers established a path and then a wagon road. The Great Wagon Road stretched southeast from Philadelphia to Winchester, Harrisonburg, Staunton, and other settlements. It ultimately reached the Holston River, where the Wilderness Road branched off through Cumberland Gap into Kentucky.

Today, I-81 runs along the eastern edge of the Valley and Ridge physiographic province. The area stretching from Pennsylvania to Tennessee is sometimes called the Great Valley.

the Potomac watershed includes the Shenandoah Valley, which can be considered a sub-unit of the Valley of Virginia, the Great Valley, and the Valley and Ridge physiographic province

Source: Water Quality in the Potomac River Basin, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia, 1992-96

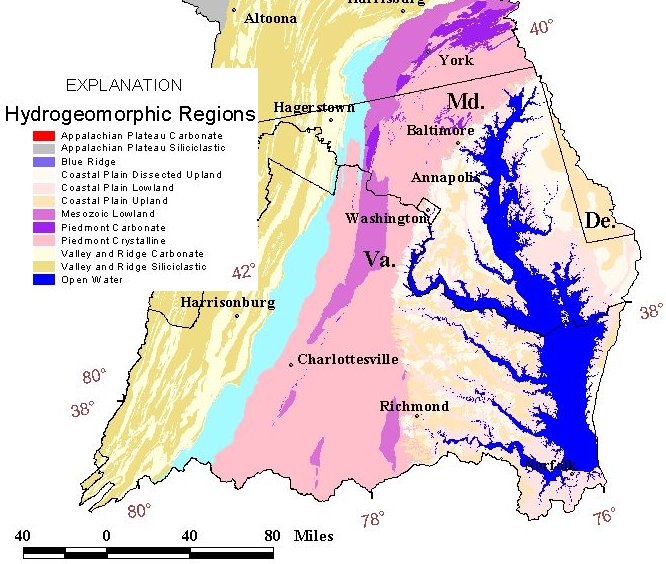

geology largely determines the availability of goundwater; wells drilled in limestone areas typically yield far more than wells drilled in the igneous Blue Ridge bedrock

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Hydrogeomorphic Regions in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed

The bedrock that defines the eastern edge of the Blue Ridge geologic province (Catoctin greenstone) extends east, beyond Charlottesville. However, erosion has flattened the eastern edge of that geologic formation.

The most active land conservation group in the Blue Ridge province calls itself the Piedmont Environmental Council, and the Charlottesville website says the city is "[s]ituated within the upper Piedmont Plateau, at the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains and at the headwaters of the Rivanna River..."2

bedrock geology of Virginia

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Tapestry and Time and Landforms Of The Conterminous United States - A Digital Shaded-Relief Portrayal

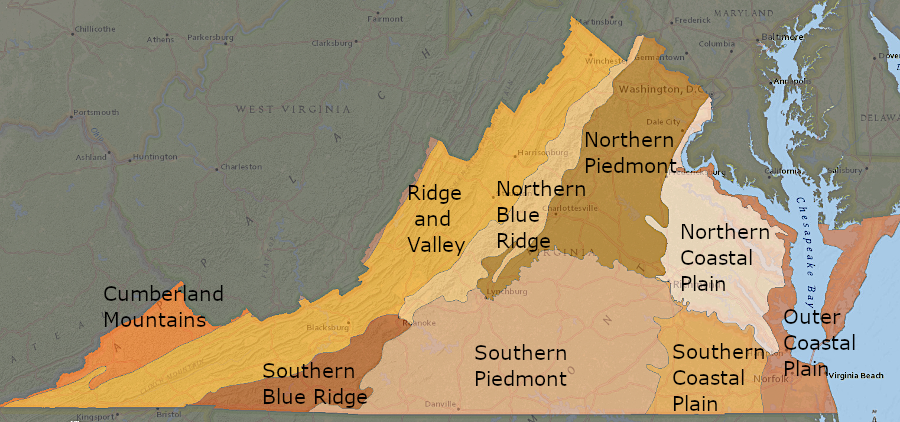

The standard list of physiographic provinces for Virginia includes:

Virginia's physiographic regions, divided into more-specific categories

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, ConserveVirginia

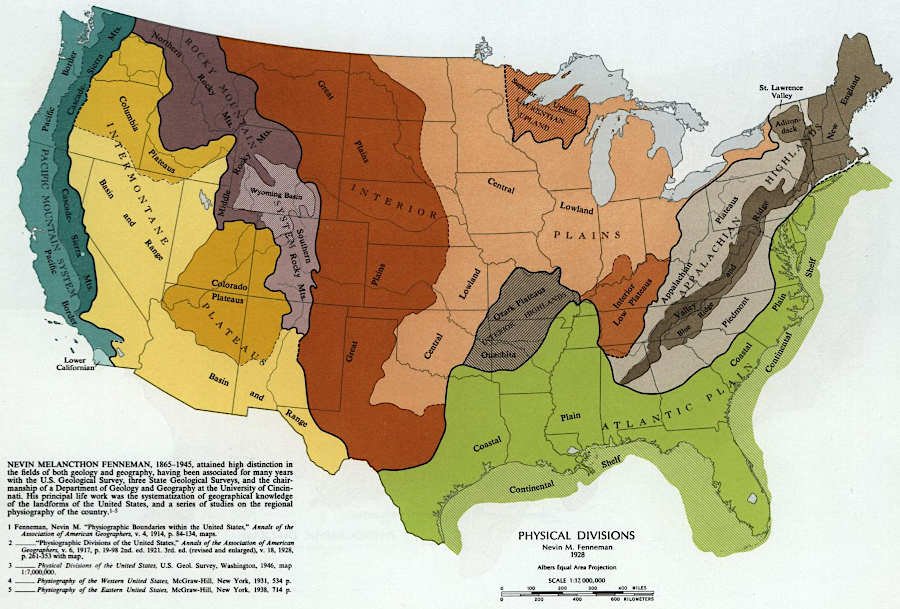

five of the physiographic regions of the United States are found in Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, "The national atlas of the United States of America," The national atlas of the United States of America (1970)

only one county (Prince William) stretched from the Blue Ridge to the Potomac River

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Map

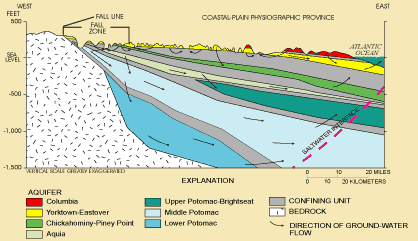

That list omits the former eastern edge of the Coastal Plain. That land has been underneath the water of the Atlantic Ocean since the ice sheets started melting faster than they were growing 18,000 years ago.

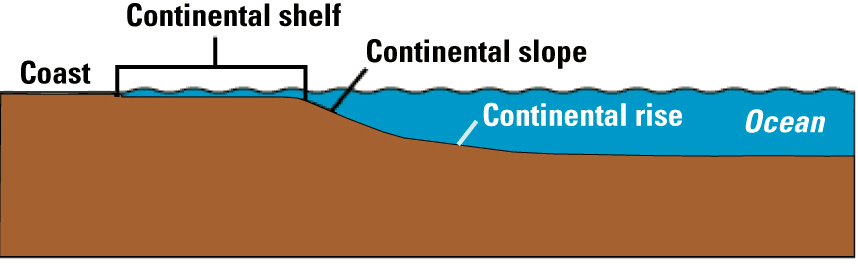

The now-submerged part of the Coastal Plain is called the Continental Shelf, and could be treated as an additional physiographic province. The Continental Shelf extends from the shoreline into the Atlantic Ocean, eastward to a depth of about 200 meters. There, edge of the continent drops down relatively steeply to the deep bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.

A "splitter," rather than a "lumper" when making classifications, might be very specific about the underwater physiographic provinces and separate the flat continental shelf from deep ocean bottom. The eastern edge of the Continental Shelf could be classified as the Continental Slope, with a separate Continental Rise near the very bottom where sediments washing off the slope have accumulated.

classification of regions east of Virginia shoreline

Source: Extended Continental Shelf Project, Article 76 and the Continental Shelf

The Continental Shelf is flat. The Continental Slope is a steep underwater hillside, droping down from the Continental Shelf to the deep ocean bottom known as the Abyssal Plain. From the beaches of Virginia out to the slope, the bedrock is still continental crust, topped by a coating of ocean sediments and a column of water above the sediments.

The Continental Slope marks the edge of the continental tectonic plate. East of the Continental Slope, the bedrock is ocean crust that consists of iron-rich basalt. The oceanic crust extends further eastward to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the range of underwater mountains in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean where basaltic magma oozes up regularly via a crack in the crust.

bathymetry showing continental shelf off Virginia coast

(the steep Continental Rise is portrayed as a thick black line to the east of the shelf)

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Atlas

John Lederer was one of the first Europeans to leave a record of his transect across the physiographic provinces of eastern Virginia. There may have been earlier European explorers, and certainly there were earlier Native Americans - but they left no written reports to document their discoveries. Some European may have beaten John Lederer to the western edge of the colony, but Lederer gets the credit.

John Lederer was one of the first Europeans to leave a record of his transect across the physiographic provinces of eastern Virginia. There may have been earlier European explorers, and certainly there were earlier Native Americans - but they left no written reports to document their discoveries. Some European may have beaten John Lederer to the western edge of the colony, but Lederer gets the credit.

There is a monument to John Lederer on Route 55 at Markham, east of Front Royal. It is located on his supposed route through Manassas Gap; there's a fair chance that he once stood at that very spot. The monument is one of the many pieces of visual clutter that, if a driver slows down and looks carefully out the window, can make traffic headaches a little less burdensome.

From the top of the Blue Ridge, Lederer saw the Shenandoah Valley and North Mountain on the western side. Even if the day was clear, however, he probably did not see the Allegheny Front in what is known today as West Virginia.

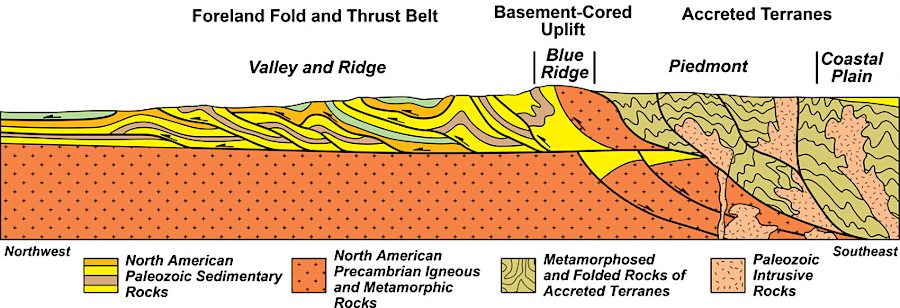

The "front" is the edge of the Appalachian Plateau, on the west side of the Valley and Ridge province. On the Appalachian Plateau, the layers of rock are no longer folded extensively, in contrast to the extensive deformation of rock in the Valley and Ridge province

The impact of Africa and North America folded and faulted the rock layers across Virginia, compressing and tilting them until the energy of the collision was dissipated. The boundary, where those rock layers were not reshaped by the collision, is the western edge of the Valley and Ridge physiographic province and the eastern edge of the Apppalachian Plateau. West of the Shenandoah Valley, the Valley and Ridge province extends into West Virginia. In Virginia, the Allegheny Front is most visible in the southwestern part of the state.

Blue Ridge and Shenandoah Valley

Lederer would have seen Massanutten Mountain clearly between his location on the Blue Ridge and the horizon. Massanutten may be a "mountain," but from both a geologic and physiographic perspective, that mountain is just one of the many ridges in the Valley and Ridge province. Geologically, the volcanic bedrock of the Blue Ridge (the location of Shenandoah National Park and the Blue Ridge Parkway) is dramatically different from the younger sedimentary bedrock of Massanutten Mountain to the west.

Massanutten Mountain splits the Shenandoah Valley

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation Highway Map

If one stands on Skyline Drive and looks west from Swift Run Gap (where US 33 crosses the mountain), it appears that south of Route 33 and Massanutten Mountain there is just one wide Shenandoah Valley. It stretches between the Blue Ridge and West Virginia. The valley (known by different names, and sometimes just called the Great Valley or Valley of Virginia) extends south down to Staunton, Lexington, Roanoke, and on to the Tennessee border.

Virginia's physiographic regions

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Ground-Water Dating to Assess Aquifer Susceptibility

It stretches north through Pennsylvania to New York. North of Route 33, Massanutten Mountain splits the Shenandoah Valley. Between the Blue Ridge and Massanutten, from Waynesboro in the south to Front Royal in the north, the eastern part of the Shenandoah Valley is also called the Page Valley. Visitors to Luray Caverns are in the Page Valley. Drivers along Route 340, and canoeists floating on the South Fork of the Shenandoah River, go through the Page Valley subunit of the Shenandoah Valley.

West of Massanutten, Interstate 81 and the North Fork of the Shenandoah River both run through the wider part of the Shenandoah Valley.

looking south into the Sheandoah Valley, from the southern peak of Massanutten Mountain

A physiographic province "lumper" rather than a "splitter" could combine all the western Virginia ridges (including the Blue Ridge) into one or two provinces. That approach would eliminate the Blue Ridge as a unique province. Lumpers could treat the Blue Ridge as just one of the many ridges in an expanded interpretation of the Valley and Ridge province. At time, cultural geographers and historians lump the Blue Ridge together with the Appalachian Plateau and refer to the "Appalachians" in various discussions of colonial history and frontier settlement.

If John Lederer had explored the mountains and plateau west of the Shenandoah Valley, with such an eye for geographic differences, he may have recognized the Appalachian Plateau as a distinct province. With that understanding, he may have separated his Highlands into two separate provinces, the Blue Ridge vs. Valley and Ridge.

Lumping can generate substantial confusion, especially regarding the definition of Appalachia. Physical geographers and cultural geographers do not always draw lines in the same places; "mountain culture" may refer to multuiple physiographic provinces. The characters in the 1960's hit TV show The Beverly Hillbillies were theoretically from the Ozarks of Missouri/Arkansas, not the Appalachians. The characters in The Waltons reflected a very different mountain culture, from the Blue Ridge Mountains southwest of Charlottesville.

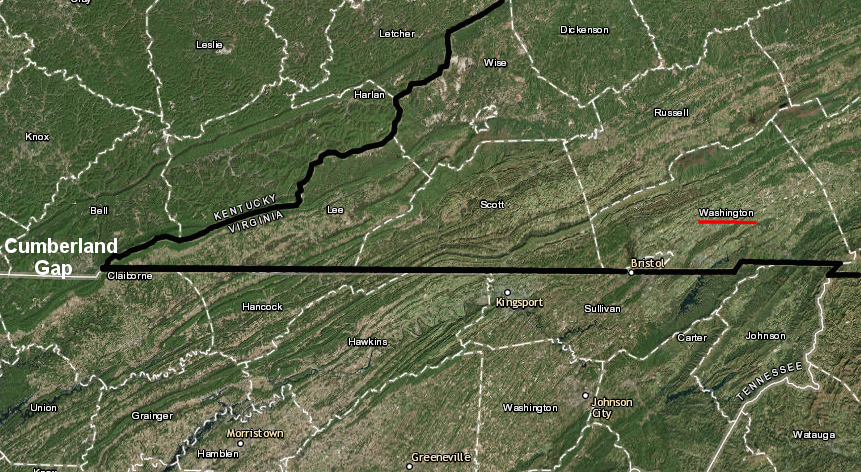

Trans-Allegheny can refer to settlement on the Appalachian Plateau, west of the Allegheny Front at the western edge of the Valley and Ridge. However, some historians write about Washington County in Southwestern Virginia and the Tenneseee Valley as part of the Trans-Allegheny region.

is Washington County in Appalachia?

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The edges of physiographic regions are not based on cultural or biological features, such as political/urban boundaries or forested/developed lands. So - why would anyone bother to define areas with consistent landforms?

The Virginia Natural Heritage Program identifies areas of special significance within separate sections of the state. That state agency uses ten separate physiographic regions for the state. It treats "Allegheny Mountains" and "Cumberland Mountains" as separate terms for the Appalachian Plateau, divides te Blue Ridge and Piedmont into northern/southern sections, and splits the Coastal Plain into three parts.

the Virginia Natural Heritage Program defines 10 physiographic provinces

Source: Virginia Natural Heritage Program, Virginia's Precious Heritage: A Report on the Status of Virginia's Natural Communities, Plants and Animals, and a Plan for Preserving Virginia's Natural Heritage Resources (see Figure 7.1)

Physiographic provinces are particularly useful for identifying natural communities and where rare/endangered species should be protected. Type in "physiographic region" or "physiographic province" in a search engine and note how many studies of birds, plants, and preservation of natural areas organize information and make recommendations based on physiographic province boundaries.

The names of physiographic regions may not match up exactly - but in many cases, the boundaries are consistent with other classification systems. The "Cumberland Plateau" of the Virginia Natural Heritage Program is equivalent to the "Appalachian Plateau" defined by others.

There are different spellings and ways of pronouncing regions in different places. Local residents vary in using Allegheny or Alleghany as the correct spelling. Similarly, Appalachia may be pronunced as Appa-lay-shia or Appa-lat-chia. Both are correct, and local residents can recognize strangers depending upon the pronunciation used.

different bedrock, formed over a billion years by orogenies, erosion, deposition, and metamorphosis, is key to distinguishing different physiographic provinces

Source: National Park Service, Tectonic Provinces of the Southern Appalachian Mountains

The edges of physiographic provinces typically are not mapped at a detailed scale, such as the 1:24,000 quadrangle maps used by hikers or the 1:400 scale plats used by county assessors for property tax purposes. Physiographic provinces are intended for general orientation, so specific sites (such as those being examined in environmental impact statements) can be put into context. Locations of property boundaries, roads, archeological sites, and wetlands are mapped with far more detail that the edges of the physiographic regions.

Some maps show physiographic provinces based on county boundaries. Obviously the straight lines defined by county surveyors do not have a direct relationship with Virginia's natural features, but organizing information by county and physiographic province can still be useful.

political boundaries of the states do not match the boundaries of physiographic regions

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Physical Divisions (Plate 2b, digitized by University of Richmond)

The boundaries of the current physiographic provinces are not permanent. Go back further in geologic time, such as 200 million years ago when Pangaea was splitting up, and the physiographic provinces of Virginia would have been dramatically different. 35 million years ago when sea level was higher, the edge of the Atlantic Ocean was roughly where I-95 is located today.

During the last Ice Age, sea levels were 350-400 feet lower and the landmass of Virginia was 40 miles wider on its eastern edge. Much of today's Outer Continental Shelf was exposed, with valleys filled with trees and wildlife. Many of Virginia's earliest archeological sites washed away in the last 15,000 years as sea levels have risen, or remain buried under salt water and sediments on the Continental Shelf.3

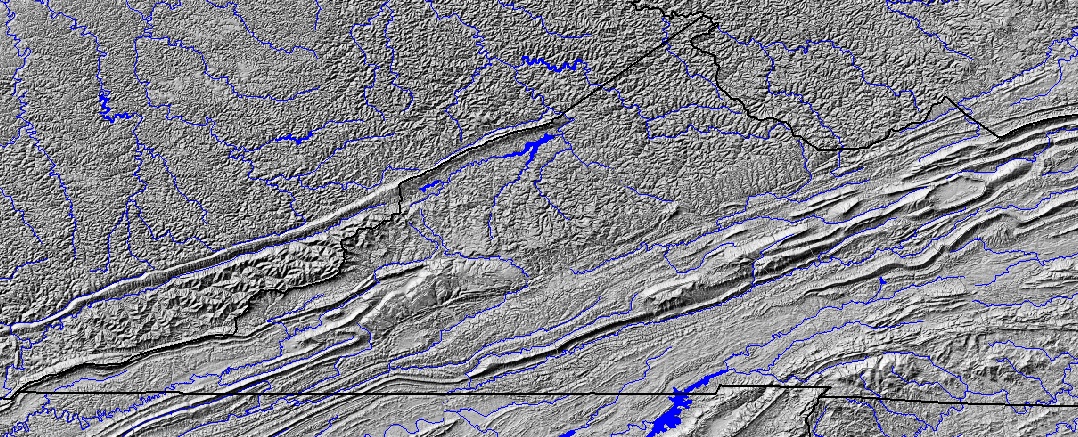

shaded relief map showing Virginia's physiography and surface hydrology - where would you draw the lines to define physiographic boundaries?

Source: Virginia Division of Natural Heritage, Overview of the Physiography and Vegetation of Virginia (Figure 1)

topography can be a clear guide to distinguish the physiographic boundary between the Appalachian Plateau vs. the Valley and Ridge provinces

Source: USGS National Map Seamless Server

Virginia's geologic bedrock can be subdivided into more terranes and categories than just the physiographic provinces

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS)

one billion year old crystalline bedrock, exposed at the Blue Ridge, is the basement complex that lies underneath the Piedmont/Coastal Plain/Continental Shelf

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), "Virginia Aquifer Susceptibility," Coastal Plain Province

physiographic provinces of Virginia

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Ground Water Atlas of the United States, Map showing physiographic provinces

slowly-eroding sandstone near top of McAfee Knob in Roanoke County