Virginia's towns were concentrated on rivers at the time of the American Revolution

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the United States of America agreeable to the peace of 1783

By the start of the 18th Century, the "First Families of Virginia" gentry (about 5% of the population) controlled how high-value lands along the rivers would be granted and patented by the Governor. Indentured servants who had completed their term of service were obliged to move inland to acquire less-attractive lands.

As settlement moved upstream into the Piedmont west of the Fall Line, transportation of crops required new techniques. Along the James River, batteaux were used to ship hogsheads downstream to Richmond. Along the Rappahannock, crops were hauled by wagon or rolled in hogsheads to Fredericksburg. Further north, Dumfries was initially a busy port but Alexandria quickly eclipsed it.

Settlement west of the Fall Line remained highly decentralized, but Fall Line cities developed in the mid-1700's as trans-shipment centers. Goods delivered on roads from the west were transferred to ships that carried tobacco to England.

Export crops of corn and wheat were also carried to the Fall Line cities, to be shipped to coastline cities in the northern colonies or to the islands - Bermuda, Jamaica, West Indies. South of Richmond, the fur trade was the initial stimulus for development of a fort on the Appomattox River (as well as early exploration of the Woods or "New" River).

Virginia's towns were concentrated on rivers at the time of the American Revolution

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the United States of America agreeable to the peace of 1783

Alexandria, Occoquan, Dumfries, Fredericksburg, Richmond, and Petersburg all developed as transportation centers initially. They competed with each other to draw the farm trade to their port, increasing the wealth of their merchants at the expense of the adjacent cities.

There was no clear physical advantage for one city to grow faster than another, in terms of deep water harbor or easier access to the "backcountry" west of the Fall Line. It was primarily the energy of the merchants that determined which Fall Line cities would grow, and which would decline.

Dumfries and Alexandria were chartered only hours apart, and the streets are laid out in the same pattern with the same names. Alexandria quickly grew into an urban center, while Dumfries was in decline even before erosion silted in the harbor.

a string of port cities developed on the Fall Line, and the post road (now Route 1) linked them together for land travel - including Dumfries, documented by French engineers in 1781-82

Source: Library of Congress - Rochambeau Collection, Amerique campagne - Dumphrys (map 15)

Today, Norfolk, Newport News, Richmond, and Baltimore are still engaged in the same competition for trade. Because state and Federal funds are used to dredge channels in the rivers and Chesapeake Bay for ever-larger ships to dock at these port cities, the competition is a political issue as well as an economic decision.

It was the same way 200 years ago, when the state helped finance a series of "internal improvements" designed to increase traffic to port cities in Virginia.

The Alexandria merchants gambled that a well-constructed highway to the interior of the state would be a good economic investment. They financed the Little River Turnpike in 1795 from Alexandria to the base of the Blue Ridge (today's US Route 236-50 to Aldie in Loudoun County). Then they supported extension of the road into the heart of the Shenandoah Valley to Winchester. This intercepted the trade going north, down the valley and across the Potomac to Baltimore and Philadelphia.

The Little River Turnpike was an economic success. Farmers who brought wagonloads of crops to Alexandria docks went home with wagonloads of goods bought from Alexandria merchants. Tolls on the turnpike repaid the investment, so the merchants expanded their reach with additional roads.

The state helped to finance transportation improvements after seeing the success of the Little River Turnpike. The Board of Public Works was finally chartered in 1816, to coordinate the investments.

The state purchased bonds to finance 40-60% of the cost for a wide variety of turnpikes, plank roads, canals, and railroads before the Civil War. After the Erie Canal drew the Ohio River/Great Lakes trade to New York City and it boomed dramatically, other states also invested heavily in efforts to steer trade from the west to their Atlantic port cities.

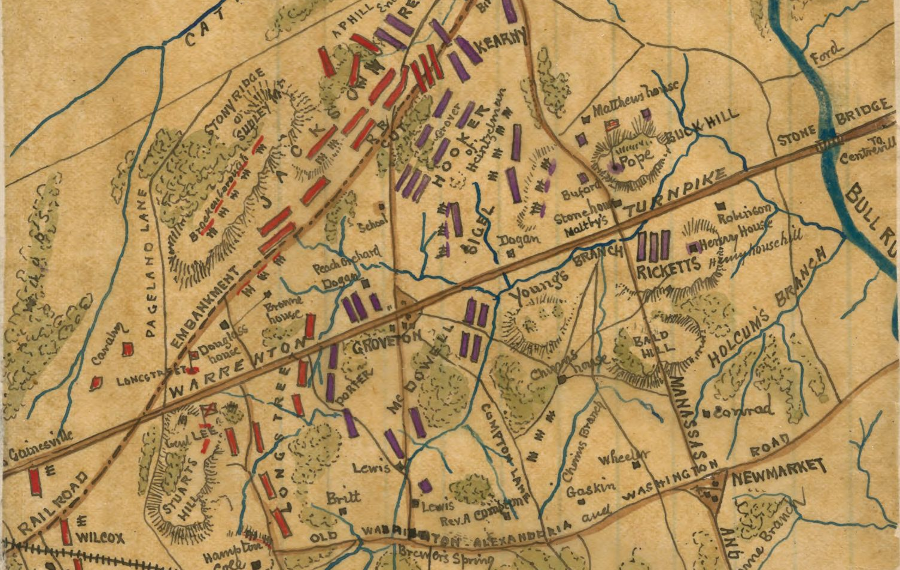

Alexandria built the Warrenton Turnpike (US Route 29 from Jermantown in Fairfax County to Warrenton in Fauquier County). It intercepted trade that might otherwise have gone to Occoquan or Fredericksburg. (In Warrenton, it was known as the Alexandria Turnpike...)

the Stone House on Manassas Battlefield was a toll station on the turnpike between Alexandria and Warrenton

Source: Library of Congress, Second Battle of Bull Run position of troops at 6 p.m.

Alexandria also supported the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, seeking to draw the trade from the Ohio River into the Potomac drainage and to their deepwater port. That was a combined investment from the national government, Maryland, Virginia, Georgetown, and Alexandria. All of these communities treated it as an investment for the long-term. They realized that their growth would be one return on their investment, even if tolls were insufficient to repay the bondholders.

An extension of the C&O Canal carried the narrow canal boats on the water-filled Aqueduct Bridge. This extension across the Potomac River to Alexandria was built so Georgetown merchants did not get all the business from the canal, and because Georgetown was too shallow for most ocean-going ships. You can still see one abutment of the Aqueduct Bridge on the north shore, upstream of the Key Bridge in Georgetown. The locks in Alexandria have also been restored, though now they are surrounded by offices instead of transportation facilities.

In the 1840's, the Orange and Alexandria Railroad extended Alexandria's reach into Culpeper and across the Rapidan to Orange County. The Manassas Gap Railroad drew traffic from the upper Shenandoah Valley to Alexandria. The planned Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire Railroad never reached the valley or the coal fields of Hampshire County (now in West Virginia), but the tracks were built to Purcellville and are the roadbed of the current Washington and Old Dominion (W&OD) bike trail.

Orange and Alexandria (O&A) Railroad station at Culpeper

Source: Library of Congress, Culpeper Court House, Va. Freight train on Orange and Alexandria Railroad

Alexandria was not the only city seeking to grow through trade. Philadelphia merchants financed the Lancaster Turnpike (today's US Route 340 in Pennsylvania) before the Little River Turnpike was completed. Richmond interests financed the Virginia Central, originally trying to reach Harrisonburg to compete for the agricultural trade in the Shenandoah Valley. They were more successful in pushing the James River and Kanawha Canal upstream and across the Blue Ridge.

And Fredericksburg invested in a canal system up the Rappahannock River, only to see the Orange and Alexandria Railroad cross just upstream at Rappahannock Station (today, Remington in Fauquier County) of their canal terminus. The Fredericksburg canal and turning basin shaped a Civil War battle (Yankee soldiers were constrained to a few crossings of the canal at they attempted to capture Marye's Heights in December, 1862), but failed miserably in the effort to shape the economic landscape of inland trade.

James River and Kanawha Canal engineering plans, at mouth of Tye River

Source: Library of Virginia

The State of Virginia was bankrupted by the effort to build these internal improvements in order to stimulate growth in the Fall Line cities. There was not enough production in the "hinterland" to justify all the different transportation projects. After the Civil War, Virginia politics were based on the dispute over full repayment of bonds vs. readjusting the debt.

Starting in the 1720's, immigrants coming to Virginia from Pennsylvania built the Great Wagon Road from the Potomac River south, "up" the Shenandoah Valley and across the watersheds of the James and New Rivers into the Tennessee River Valley. Different towns were developed along the path to provide services to nearby farms. Each county courthouse, from Frederick County to the Tennessee border, was located on the route taken by the immigrants.

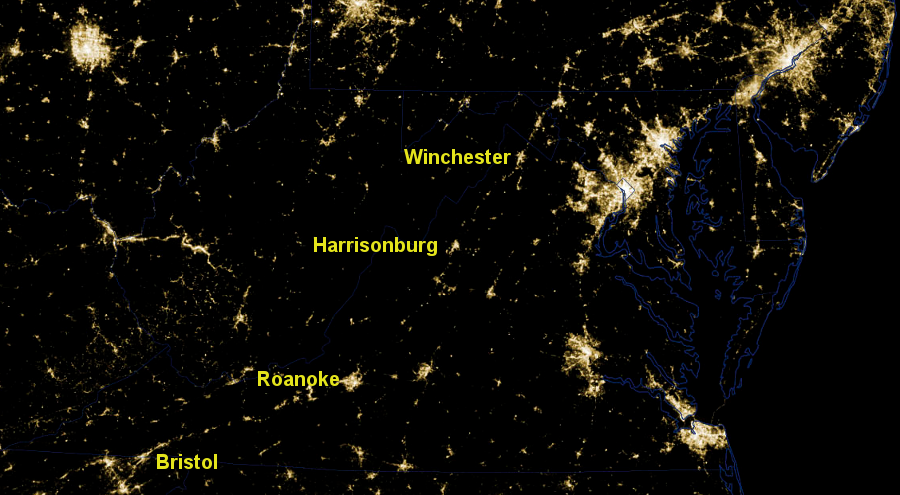

the line of cities along I-81, revealed by the pattern of lights at night, reflects the historic pattern of development since the 1700's when immigrants coming from Pennsylvania extended the Great Wagon Road on the west side of the Blue Ridge south into the Cumberland Valley of Tennessee

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Earth Observatory, Power Outages in Washington, DC Area

The largest amount of traffic was through the Shenandoah Valley, as residents west of the Blue Ridge engaged in commerce with Philadelphia. Starting in the 1830's, the portion of the Wilderness Road between Winchester-Staunton was converted into the Valley Turnpike. It was a hard-surface road, "paved" with layers of rocks of different size according to the pattern developed by John McAdam. The Valley Turnpike, perhaps Virginia's best road for 70 years, was funded by tolls until it became clear that reconstruction/maintenance costs to support automobiles would exceed revenues. The state of Virginia assumed responsibility in 1918, ending the tolls.

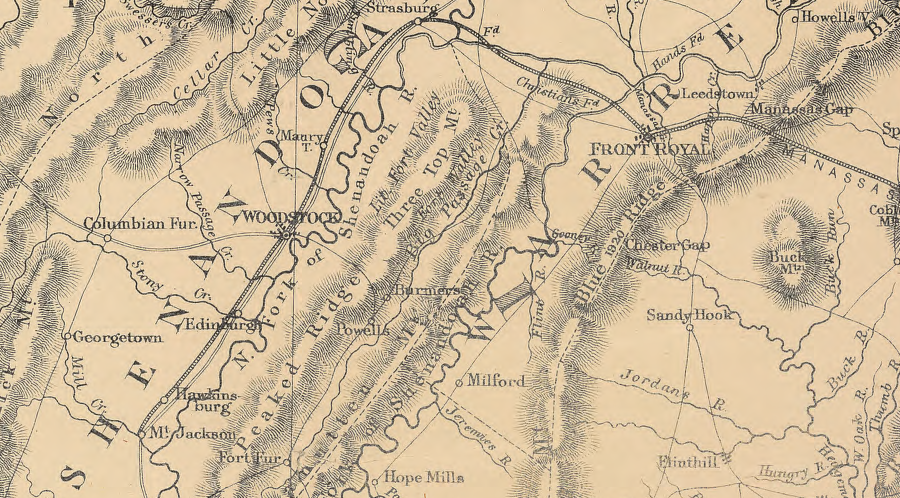

in the 1850's, the Manassas Gap Railroad linked the towns that were already established along the old Wilderness Road

Source: Library of Congress, Seat of war in Virginia, &c. (1860)

The last manager of the turnpike company was Harry Byrd, a Winchester resident who became Virginia's most powerful politician in the 20th Century. Harry Byrd's rise to political domination in Virginia was triggered by his opposition in the 1920's to a new series of bonds to finance highway construction. Instead, he initiated a "pay-as-you-go" philosophy, using automobile license fees and gasoline taxes rather than bonds or general revenues, to build the biggest state-financed internal improvement of the 1900's: paved roads.

Leesburg Turnpike though Bailey's Crossroads was a dirt road during the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, Bailey's Cross Roads, Va

Some linear strings of cities developed at locations independent of roads or railroads that linked them together. The port cities on the Fall Line, from Petersburg to Alexandria, were established because of the geological feature that determined the head of navigation. The "post road" that linked them was not the reason those towns were chartered at their sites; the Fall Line determined where humans would concentrate together on the edge of the Piedmont/Coastal Plain.

The Wilderness Road evolved at the same time as the small towns along that route. West of the Blue Ridge, transportation improvements (including the Valley Turnpike and the Manassas Gap Railroad) came after the location of most communities was fixed. Some towns along the railroad lines, such as Manassas and Roanoke, developed only after railroad junctions were built.

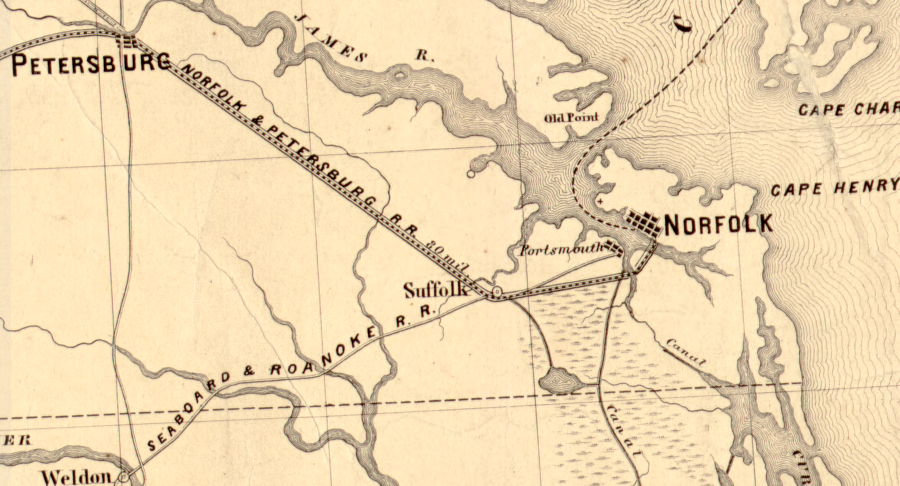

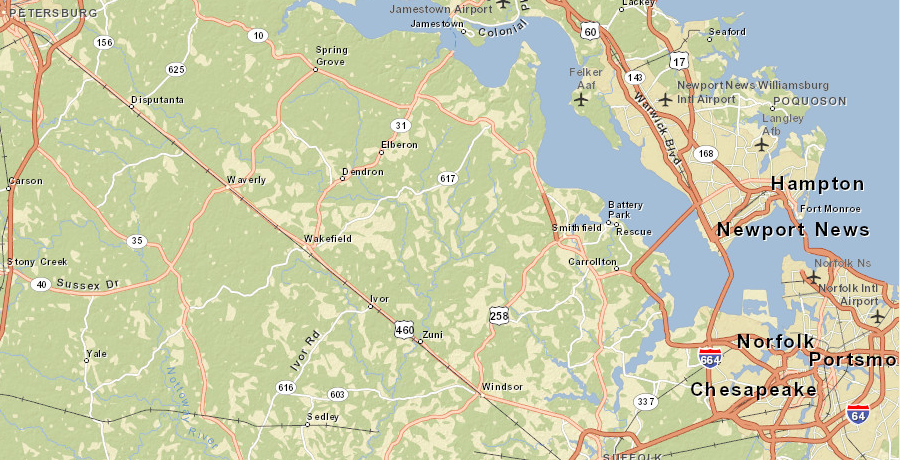

The most obvious example of where a string of communities developed due to a transportation project is southeast Virginia. When William Mahone built the Norfolk and Petersburg railroad in the 1850's, he laid out an unusually-long stretch of straight "tangent" track between Suffolk and Petersburg. There were no communities generating traffic and worth deviating from the straight line.

when the Norfolk and Petersburg railroad was built, there were no towns between Suffolk-Petersburg

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing route of Norfolk & Petersburg Rail Road and its connections with Ohio & Mississippi Rivers

The towns of Windsor to Disputanta were built in a straight line along the railroad, initially as depots where steam locomotives needed a new supply of water. A 2-lane road, US 460, was built in the 1930's to link the towns. That road was widened twenty years later, and in 2012 the state proposed to build a new 4-lane toll road to bypass those towns. The new toll road was expected to be equally straight, parallel to the current US 460, but that route would have impacted too many acres of wetlands. Bypasses looping around the towns may be constructed, adding loops to the linear pattern.1

William Mahone and his wife named the stops built along the Norfolk and Petersburg railroad, from Windsor to Disputanta, to supply water to steam locomotives

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online