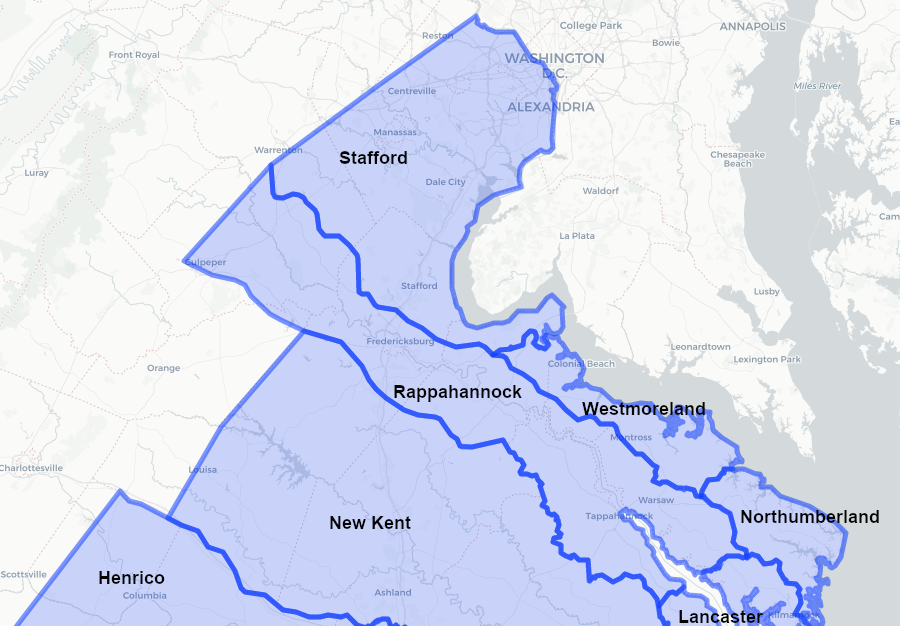

Parson Waugh's tumult in 1689 was centered in Stafford County

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

The original tribes discovered by John Smith are no longer living as intact units in Northern Virginia, but they did not disappear without a fight. One of those struggles is documented as "Parson Waugh's tumult" in 1689.

That period of conflict reflects more than just the pressure by Europeans to displace Native Americans in order to seize their land. The "tumult" was stimulated in large part by the rivalry between Catholic nation of Spain and the Anglican nation of England. In North America, that conflict was mirrored by social tensions between the Catholic colony of Maryland and the Anglican colony of Virginia, and the intolerance within Virginia of its Catholic residents.

The rivalry between Catholic Spain and Protestant England was partly over control of the church, which in theory could control beliefs and behavior of the people in the nation. The king of England was head of the Church of England. The first meeting of the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1619 was in the largest building in the settlement - the Jamestown church. In colonial Virginia, there was no separation of church and state until disestablishment by the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom in 1786.

It was a major shock in Jamestown when Charles I granted Cecil Calvert, Lord Baltimore, a colonial charter for Maryland in 1632. The Calverts were Catholics, and two Jesuit priests arrived with the first settlers in 1634. Land across the Potomac River that the Virginians thought was "theirs" was now going to be settled by people with a different faith.

In 1648, as the English Civil War heated up, Lord Calvert appointed a Protestant governor, William Stone. In 1649 the Maryland General Assembly passed the Maryland Toleration Act. It guaranteed freedom of worship to all Christians who professed belief in the trinity (Father, Son, and Holy Ghost), adding a layer of legal protection for the Catholics as well as the Puritans who were recruited to the colony.1

Spanish Catholics were not welcome in any of the English colonies in North America, despite the religion of the Calverts. In France, the Catholics were the dominant group in control of the country under Catholic monarchs. Though some Catholics from England chose to move to Maryland, most immigrants to the colony were Protestants.

By 1676, the Catholics ruling the proprietary colony were in the minority; three-fourths of the residents were Protestants. There was regular conflict between the Catholics and Protestants over use of Maryland taxes and publicly-funded buildings to support the rival faiths. After Charles Calvert took control as the third Lord Baltimore in 1676, Catholics were given appointments to colonial offices and Protestants grew rebellious under the discrimination.2

Across the Potomac River from Maryland, the number of English colonists increased in Virginia. The Protestants expanded upriver, and increasingly asserted power over Native American territory.

All of Northern Virginia was included within Stafford County when it was created in 1664, but the General Assembly made no arrangement with the Native Americans in the region to acquire their claims to the land. The colonial governor in Jamestown issued land grants to territory occupied by the Moyumpse/Dogue, and tobacco "quarters" were established in areas where they used to raise corn and hunt.

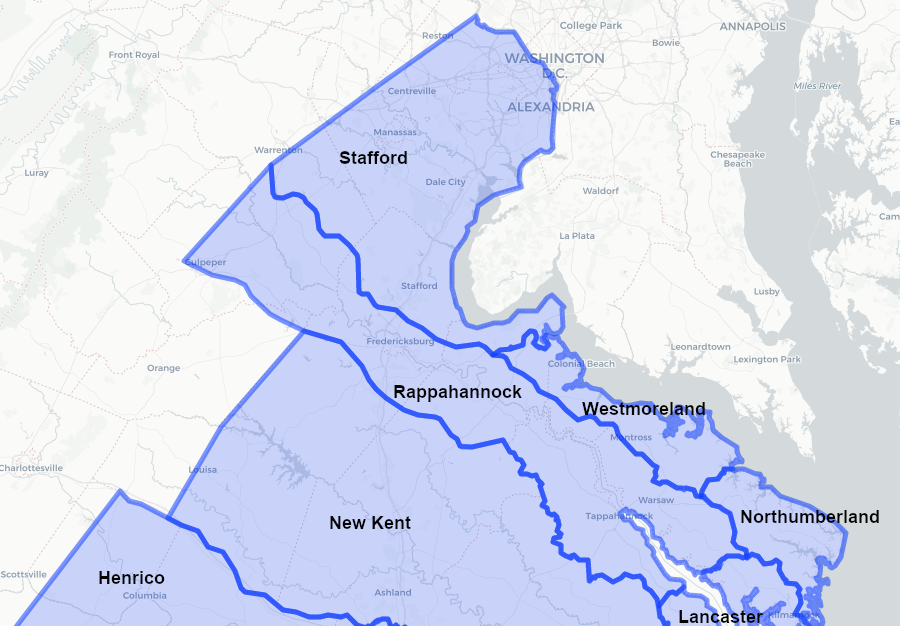

Parson Waugh's tumult in 1689 was centered in Stafford County

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

After Bacon's Rebellion in 1676, Stafford County was the edge of colonial settlement in Virginia. Native Americans no longer controlled the land, but neither did the English. Not surprisingly, at times there was armed conflict between the two societies.

To complicate the issue even further, in 1649 all of Northern Virginia between the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers had been granted by Charles II to seven of his allies in the fight to regain the throne. The grants would initially be consolidated under the authority of Lord Culpeper and ultimately under the ownership of Lord Fairfax.

At the end of the 1600's, trying to establish ownership of land north of the Rappahannock River was unusually challenging. Land titles were clouded by the conflicting authority of colonial officials in Jamestown and land agents for Lord Culpeper, as well as the presence of the Native Americans.

The timing of Parson Waugh's tumult was triggered by the Glorious Revolution of 1688 in England. Catholic James II had succeeded his brother Charles II in 1685. In 1687, James issued a Declaration of Indulgence in 1687, giving Catholics equal rights. The Anglican Parliament in London lost its willingness to accept James II as king only when his wife gave birth to a son. Rather than allow a second Catholic king to replace James II, the Anglican leaders in England forced James II to flee. In the 1688 Glorious Revolution, new Protestant rulers William and Mary replaced James II.

The parson of Parson Waugh's tumult was John Waugh. He was the Anglican minister of Overwharton Parish (now in Stafford County) from 1670-1700. Parson Waugh may not have been a sophisticated man, but he was forced to deal with complex challenge of preaching "do unto others as they would do unto you" in a setting where indentured servants, slaves, Native Americans, and the gentry competed for land, status, and personal freedom.

The Overwharton Parish congregation was not filled with people willing to defer automatically to the minister's judgment. Opportunities for conflict management were endless. As a matter of self interest, the minister had to keep the vestry (members of the gentry who managed the parish) satisfied to ensure annual renewal of his contract.

Despite the difficulties, a minister's job on the edge of colonial settlement was not a well-paying assignment. Ministers were supported by taxes on local residents and land set aside as a "glebe" for the minister to raise his own crops. On the frontier the land was not as valuable as in settled areas, and the tobacco was usually lower-quality. As a result, the better-educated, more capable ministers were rarely assigned to Northern Virginia parishes in the 1600's.3

In 1689, after Catholic James II had been dethroned and before Protestant William and Mary had become the new rulers in England, Waugh was an effective anti-Catholic agitator. Instead of ministering to soothe concerns within the congregation and inform its members, he created unjustified fear in the community.

The tumult began when Native Americans started traveling across the Potomac River from Maryland to hunt in March, 1689 (1688 by the Old Style calendar). A settler fishing in the River, Burr Harrison, initially reported the hunters were moving into the backcountry of Stafford County.

Burr Harrison claimed to have interviewed one, who reportedly said that the Piscataway king had hired the Seneca to kill the Protestants before news of the accession of William and Mary arrived in Virginia and Maryland. Ships loaded with soldiers were supposedly sailing across the Atlantic Ocean. When they arrived, Harrison claimed his Piscataway informant said the Protestants would kill the Catholics and then the Native Americans.

Another alarmist claimed 9,000 French and Seneca had landed at Anne Arundel. Lawrence Washington received a report that there were 10,000 "foreign Indians" (i.e., not from local tribes) at the headwaters of the Patuxent River.4

Rev. John Waugh used his position to spread rumors that the Native Americans in Maryland were conspiring with the Catholics to kill the Anglicans. He claimed that the Brent family in Stafford County was part of the conspiracy.

George Bent had moved from Maryland to Virginia in the 1660's, become the law partner of William Fitzhugh, and successfully speculated in lands where his servants and slaves raised tobacco. Together with William Fitzhugh and two others, he purchased 30,000 acres from Lord Culpeper to establish Brent Town in western Stafford County. The four land speculators got King James II to declare that religious worship there by Huguenots or Catholics would be tolerated, which threatened the status of the Anglican minister responsible for Overwharton Parish.

The Brents were not friends with the local Native Americans. In 1675, George Brent had been one of the leaders of the militia that attacked the Moyumpse/Dogue, Susquehannock, and Piscataway. He also led militia forces in 1684 to protect settlers against attacks by Iroquois raiders from the north, traditionally described as the Seneca even if other tribes were also involved.5

Though Catholics, the Brents became part of the local Westmoreland County and then Stafford County establishment. George Brent even held public office, including surveyor, attorney general, and militia leader. He was the only Catholic ever to serve in the House of Burgesses, in 1688. The family was given a certificate in 1668 by the Stafford county court, confirming they had not sought to create any converts to the Catholic faith in the last 21 years of their presence in the county.

Parson Waugh chose to inflame suspicion of Catholics, in particular the Brent family. He created a fear that the Virginia colonists were under imminent threat of attack. Waugh incorporated into his claims that James II's flight from England left the colony unprotected and without government authority. He asserted that the royal officials in Jamestown were no longer legitimate, because if there was:6

Settlers in the Rappahannock River watershed began to listen to Parson Waugh, and the gentry had difficulty restoring law and order. The county court ordered the Brent family to stay at William Fitzhugh's house, which provided a combination of both house arrest and greater personal safety. The court also searched Brent's house, then announced that he had no stockpile of weapons for use by French or Native American invaders. Wealthy, Anglican friends vouched for the Brent family loyalty and protected them from potential harm.

Ultimately the colonial government in Jamestown arrested Waugh and two other agitators, ending what could have grown into a full-scale insurrection. They were forced to go in front of the General Court in Jamestown, deny their previous claims, and ask for forgiveness for disrupting the peace. The court imposed no other punishment.7

Parson Waugh returned to Overwharton Parish, which had been named for his home. He had preached there since being hired in 1670 and continued until 1700. Waugh was aligned with George Mason II, who married his daughter.

After getting forgiveness from the General Court, the Waughs and Masons maintained their alliance and a faction that contested for power with William Fitzhugh and George Brent. Waugh and Mason helped Martin Scarlett defeat William Fitshugh when he ran for re-election to the House of Burgesses in 1691, made slanderous aspersions, and continued to question the loyalty of the Brents.8

Across the Potomac River, the anti-Catholic agitation had a greater impact. The Protestant Associators, agitated by another Anglican minister named John Coode, seized control of the Maryland colony in 1689 by capturing the State House in St. Mary's City. The Calverts were removed from office, the colony's capital was moved from St. Mary's City to Annapolis, the Anglican Church was established in Maryland, and Catholics were forced to pay an extra tax.9

The Catholic challenge to the authority of Protestants in Northern Virginia disappeared when Catholic control over Maryland ended.