Natural Gas Resources in Virginia

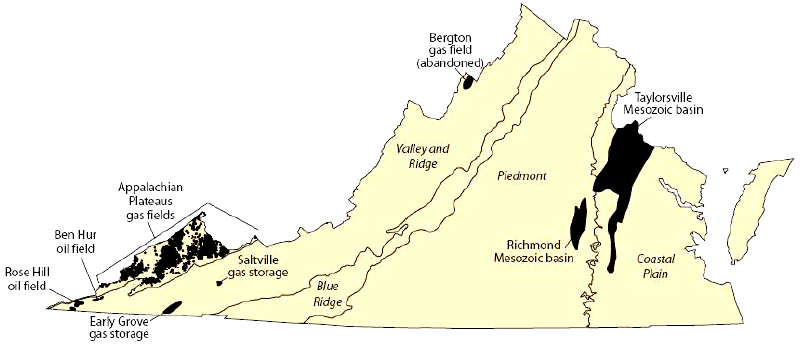

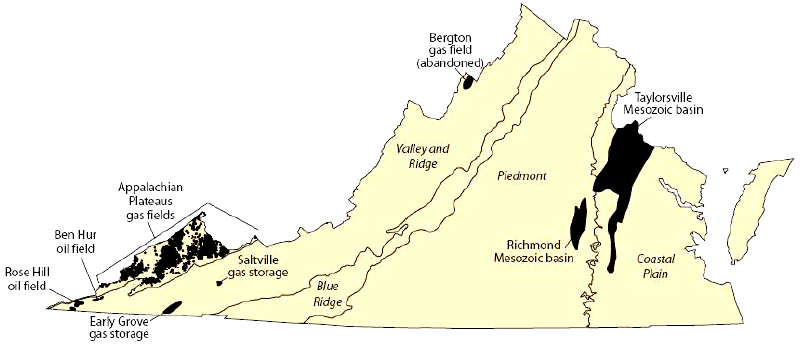

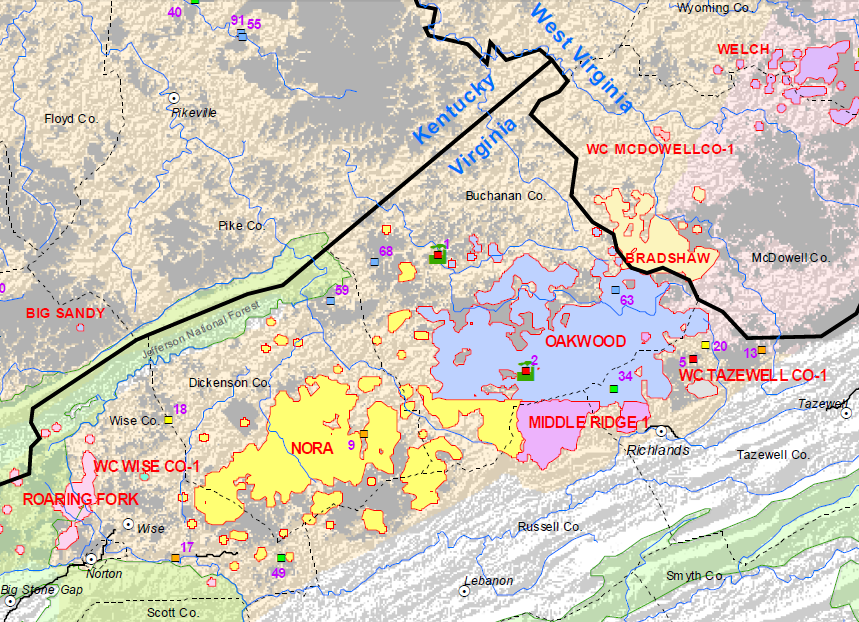

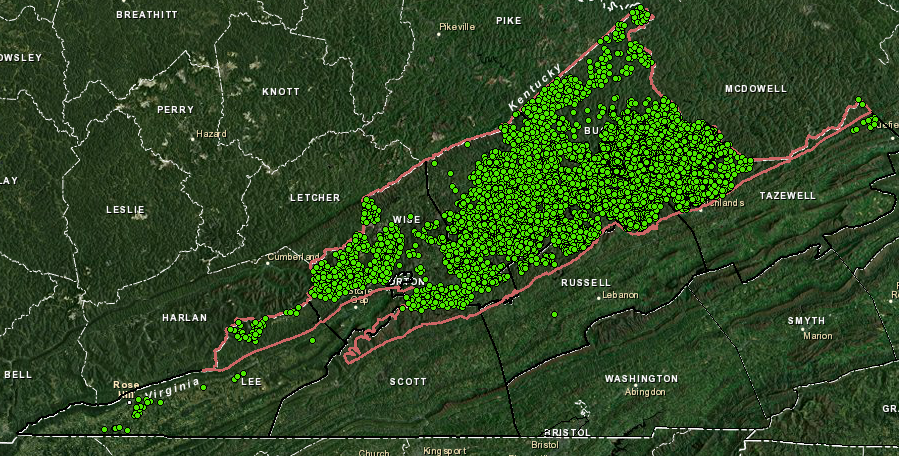

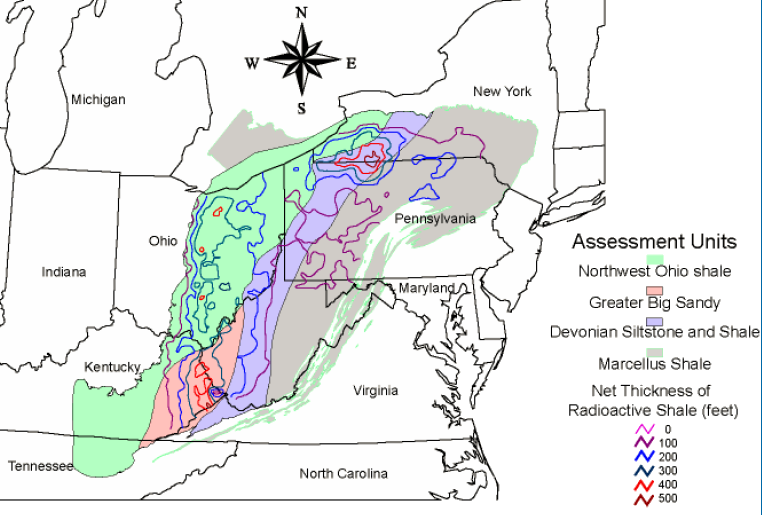

location of potential petroleum resources in Virginia (and two natural gas storage reservoirs)

Source: US Geological Survey, Assessment of Undiscovered Natural Gas Resources in Devonian Black Shales, Appalachian Basin, Eastern U.S.A. (Open-File Report 2005-1268)

The "burning springs" of the Kanawha River, where natural gas escaped from underground and occasionally caught fire, revealed the presence of hydrocarbons to Native Americans and colonial settlers in Virginia. George Washington, who always had an eye for valuable real estate, acquired some of the burning springs in 1775.

In the 1840's, the natural gas was used to boil saline water from nearby wells to produce salt. Evaporating brine on the Kanawha River was the first commercial use of natural gas in the United States.1

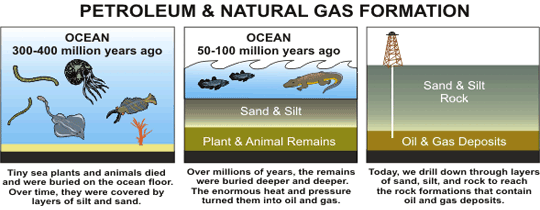

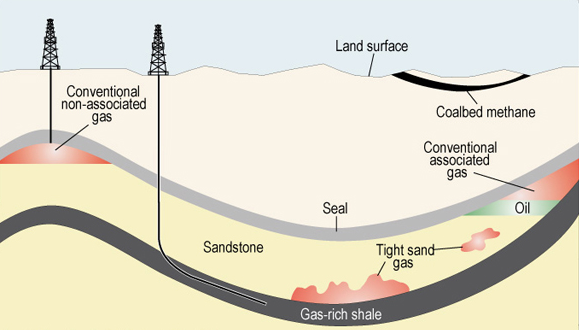

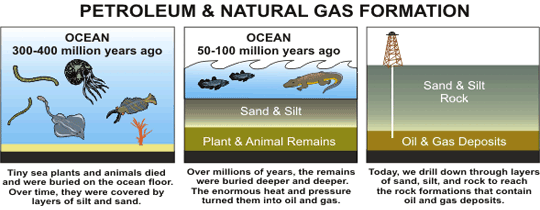

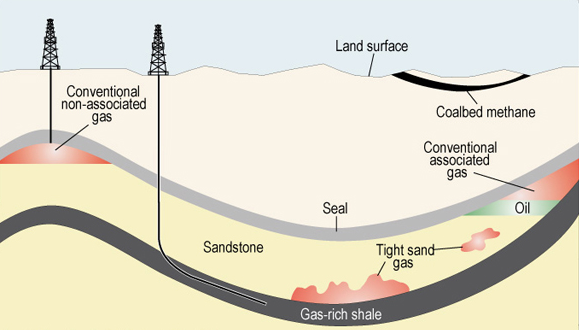

When methane is generated by vegetation rotting underwater, bubbles of "swamp gas" rise to the surface and the gas diffuses into the atmosphere. The natural gas in rock formations deep underground also was created by decomposing organic material, primarily phytoplankton and zooplankton deposited up to 400 million years ago at the bottom of oceans/lakes or in swamps.

The lipids in each tiny unit of plankton was buried and covered by younger sediments, so the gas resulting from decomposition was trapped in the bedrock. Natural gas fills pores in the bedrock and migrates only until an impervious rock formation blocks further movement. Once a driller creates an artificial path by cutting a hole through the rock layers, the gas finally can rise up to the surface via the wellbore.

decomposition of vegetation in swamps generates methane at the surface where it naturally escapes to the atmosphere, while the "burning springs" of the Kanawha River were fueled by gas escaping from deeper underground

The burning springs harnessed to boil saltwater are now in West Virginia. In what is still Virginia, the first exploratory oil/gas wells were drilled in Wise County in the 1890's. In the 1930's, the Early Grove gas field was developed in Scott and Washington counties, and in the next decade commercial oil wells were developed at the Rose Hill field in Lee County.

Liquid oil in commercially-recoverable quantities is rare in Virginia, but natural gas is more common. Heat and pressure from the movement of tectonic plates has baked the organic materials hot enough to convert most oil into gas. By 1950, roughly 140 oil and gas test wells had been drilled in southwestern Virginia, including a 9,300 foot "dry hole" in Price Mountain near Blacksburg.2

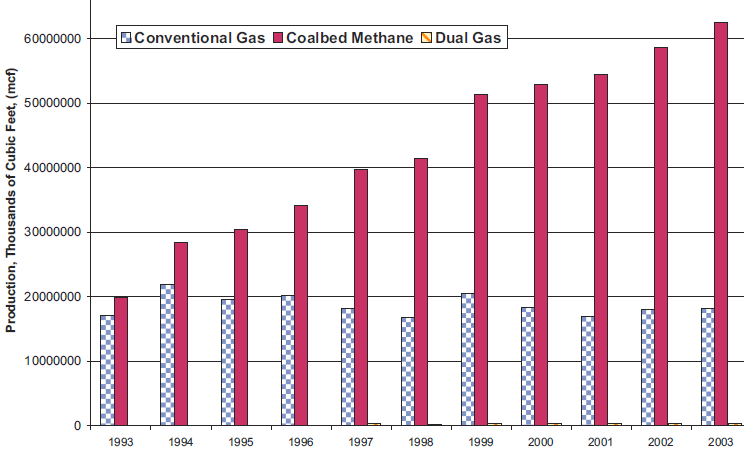

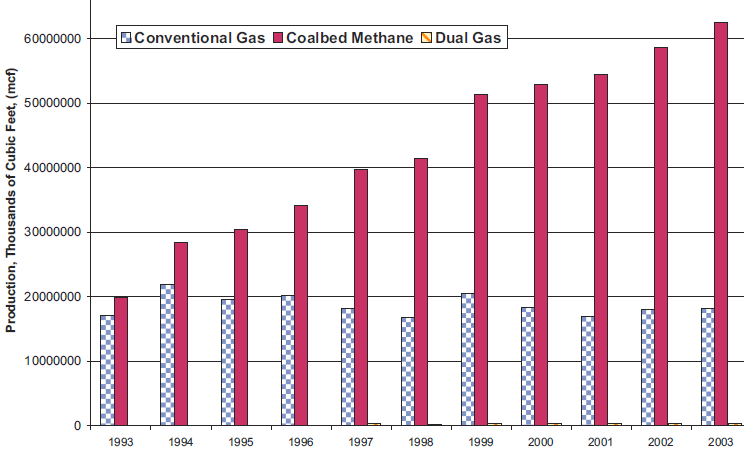

Virginia's natural gas production by type, 1993-2003 (increased natural gas production is due to coalbed methane wells)

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy, Mineral And Fossil Fuel Production In Virginia (1999-2003) (Figure 45)

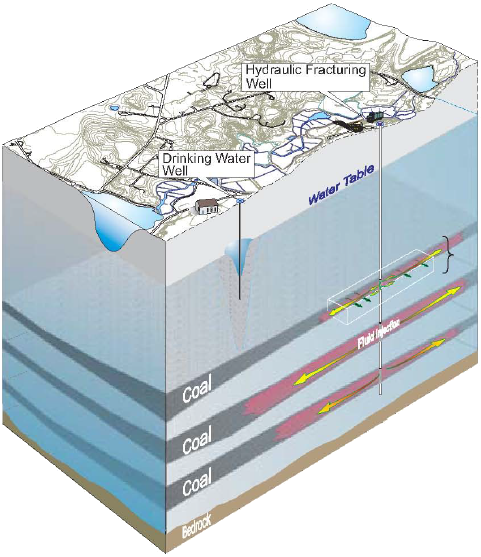

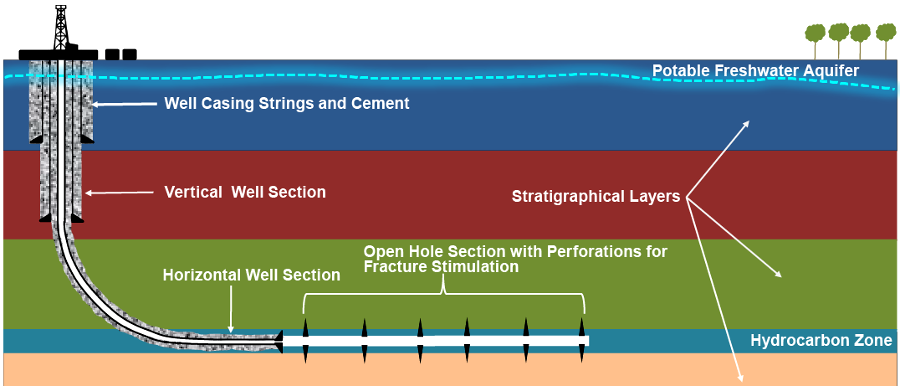

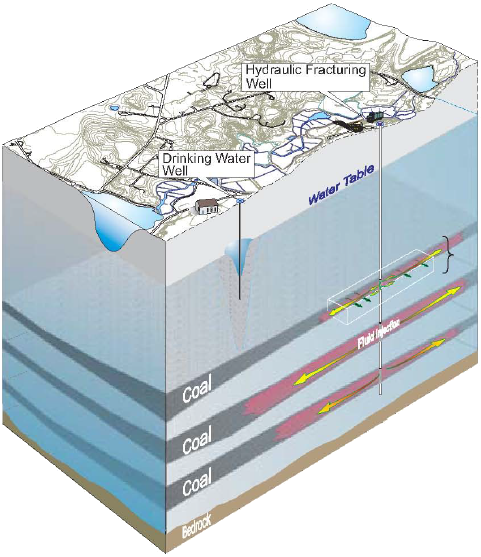

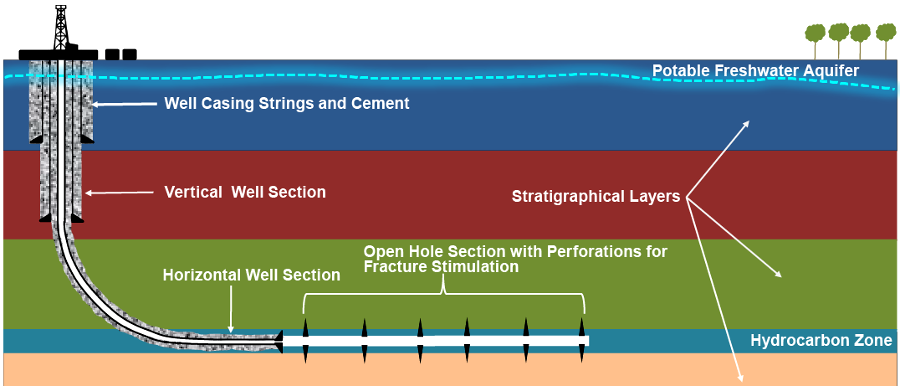

In 2012 there were 1,800 conventional natural gas wells and 5,600 coalbed methane wells in Virginia. Conventional gas wells are drilled to sedimentary layers 3,000-6,000 feet underground, while coalbed methane wells are drilled to relatively shallow depths of 1,800-2,200 feet. Gas wells are drilled far deeper than the depth of drinking water wells, which are usually drilled to 100-400 feet.

Aquifers with fresh water are encountered deeper, so gas wells drilled to sedimentary layers are "cased" (isolated from the bedrock with steel tubing) when passing through fresh water zones. The shallower coalbed methane wells pump out whatever water is trapped in the formation, to enable the methane to travel through the pores.

Because gas is lighter than rock, it will rise to the surface if given a path. Drilling operations can create fractures in the overlying formations created, and artificial fracturing of underground rock formations could also propagate cracks, potentially allowing methane to escape to the surface and pollute drinking water wells in rural areas of Virginia.3

coalbed methane and Devonian shales with natural gas are located thousands of feet deeper than aquifers used for drinking water

Source: Environmental Protection Agency, "Evaluation of Impacts to Underground Sources of Drinking Water by Hydraulic Fracturing of Coalbed Methane Reservoirs Study," Executive Summary (Figure ES-2)

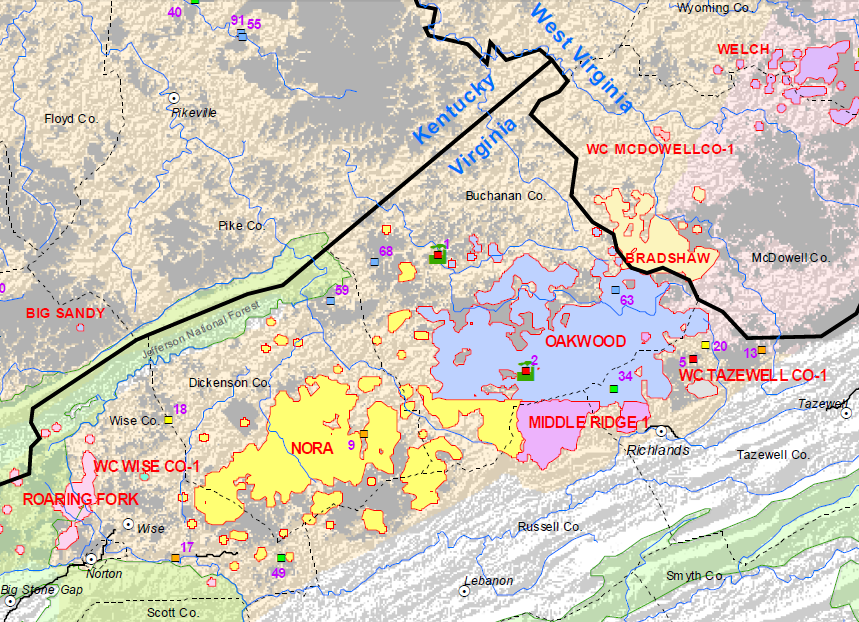

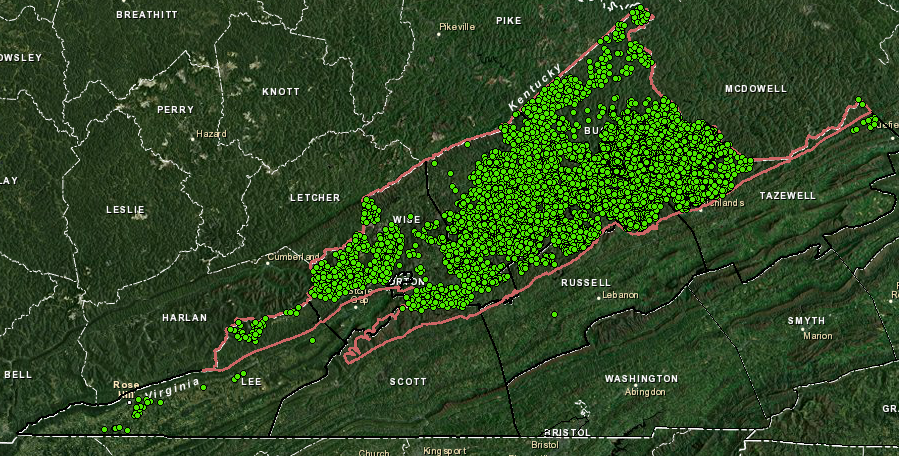

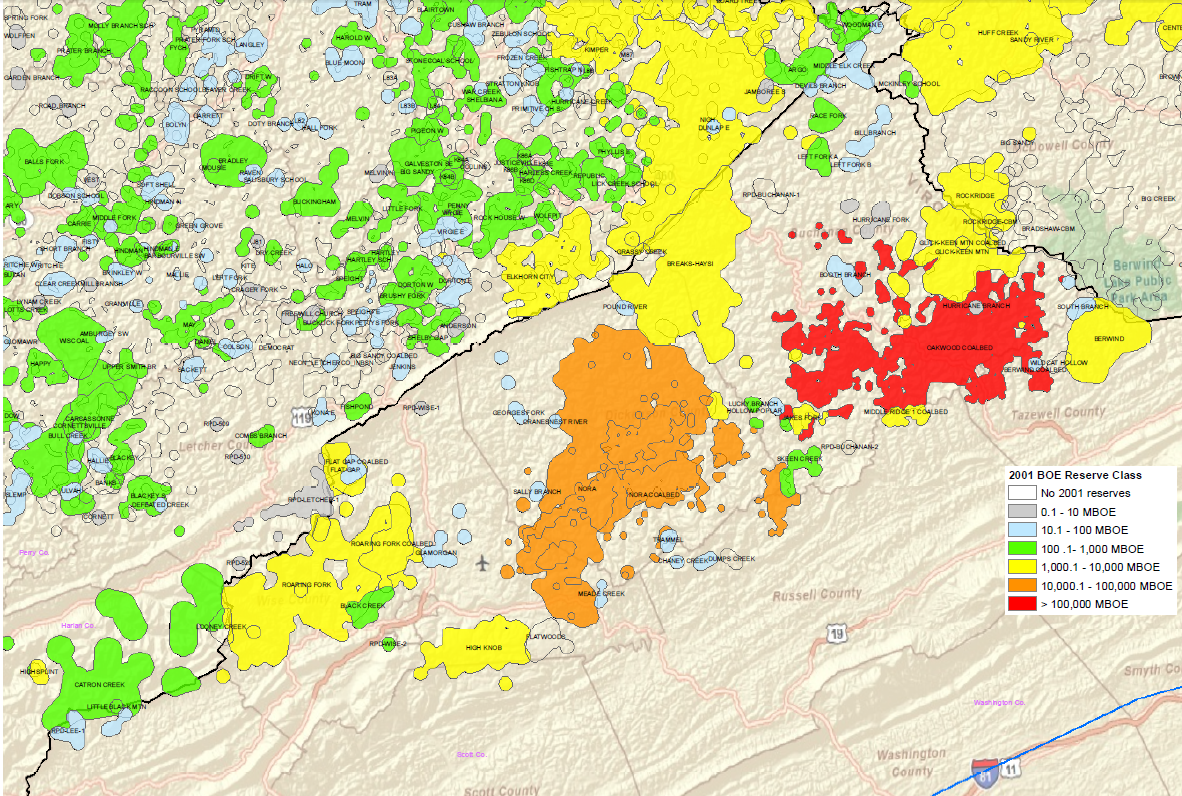

Roughly 80% of the natural gas produced in Virginia comes from the "unconventional" coalbed methane wells, primarily from the Oakwood, Nora and Middle Ridge fields in the Appalachian Plateau. The desired product from coalbed methane wells is primarily methane (CH4).4

Nora, Oakwood, Middle Ridge, and other coalbed methane fields in Southwestern Virginia

Source: Energy Information Administration, U.S. Map showing CBM exploration (July 2007)

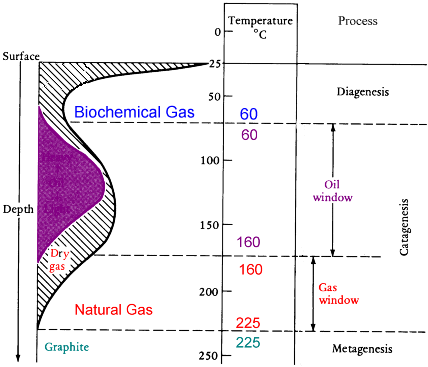

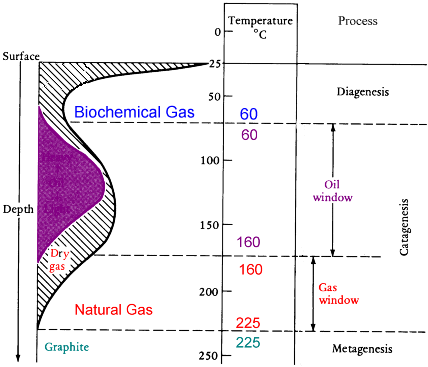

Natural gas can be extracted from oil wells, or from rock formations where it is not associated with oil. Oil and gas are formed underground by the decomposition of organic material. At relatively low temperatures, oil can form under heat/pressure levels within the "oil window" and remain as a liquid. Under higher pressures and temperatures, liquids are volatized into gas molecules - methane (CH4), ethane (C2H6), propane (C3H8), butane (C4H10), and other gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S).

heat/pressure are required to convert organic-rich marine sediments into oil, but additional heat/pressure will transform liquid oil into natural gas

Source: Louisiana Department of Natural Resources, Petroleum Transformation

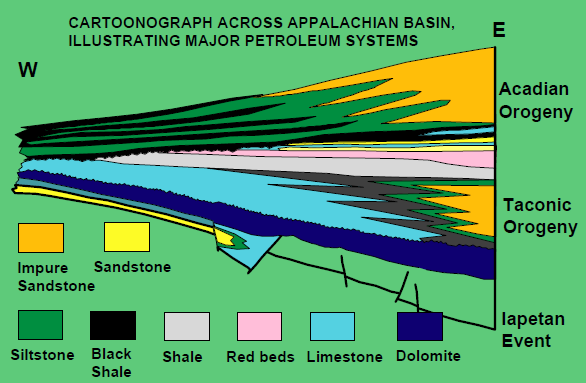

Virginia has little potential for expanded oil production, except potentially from under the Outer Continental Shelf. The Taconic, Neo-Acadian, and Alleghenian orogenies compressed most sediments west of the Fall Line beyond the oil window, and liquid hydrocarbons were vaporized by heat/pressure into gas. The oil was converted into gas molecules that rose to the surface and escaped into the atmosphere, or accumulated in porous rocks that have an impervious caprock blocking further migration.

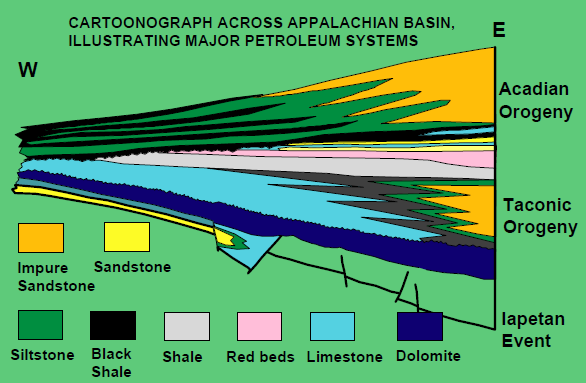

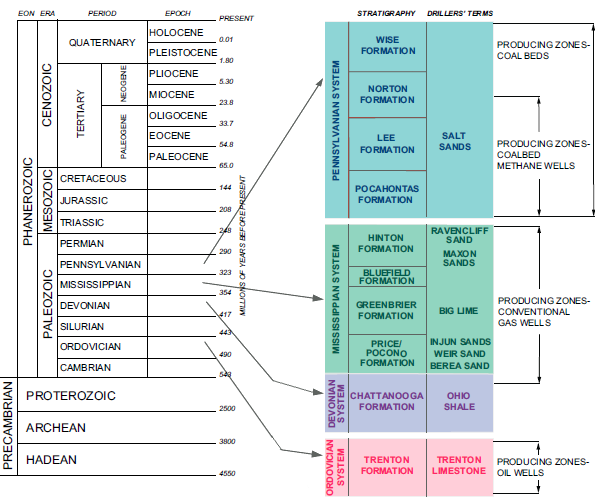

Virginia's conventional natural gas, in Devonian Period formations, is derived from sediments deposited 350-400 million years ago

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Natural Gas Explained

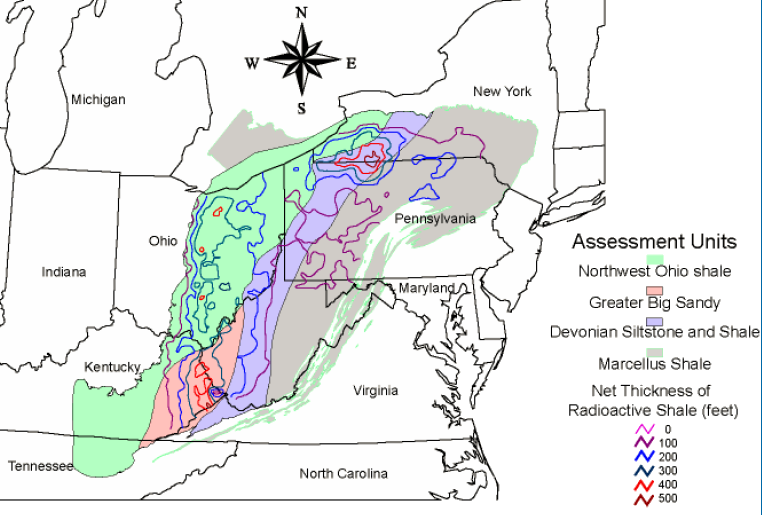

Some hydrocarbon molecules may be trapped in the original sediments deposited millions of years ago, if the gaps between particles in those layers of rock are so small that "tight sediments" keep the gas trapped at the source. Virginia's greatest potential for increased production of conventional natural gas lies within those Devonian shales near the West Virginia border, where vertical wells could be drilled to extract the hydrocarbon resource migrating within source rocks with 1-2% organic material (OM).

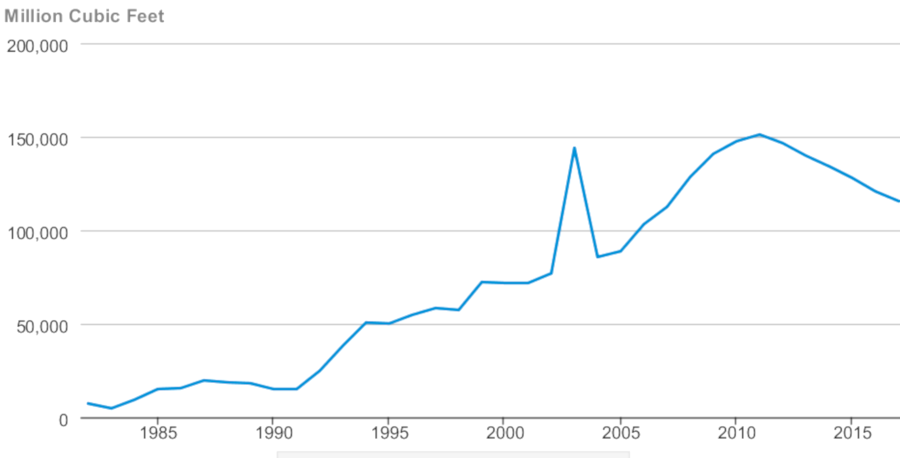

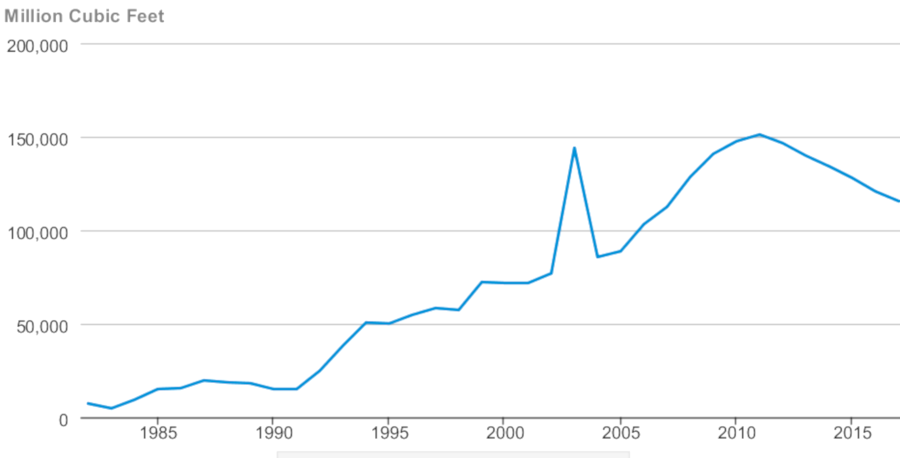

Virginia's natural gas production hit a peak of 151,094 million cubic feet in 2011

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Virginia Dry Natural Gas Production

On the western edge of the state, sediments deposited during the Devonian Period (350-400 million years ago, at roughly the same time as the Acadian orogeny) have gas molecules trapped underground. In the 1980's, five exploration wells were drilled into the middle Devonian Oriskany Sandstone during exploration of the Eastern Overthrust Belt. None of the five discovered commercial quantities of natural gas.5

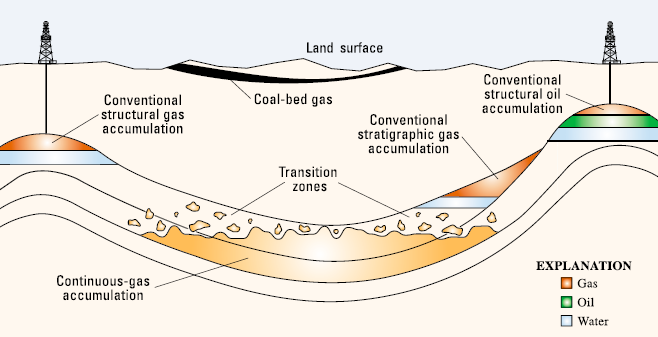

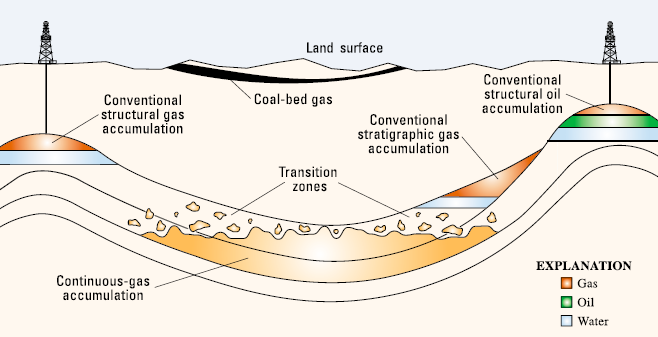

oil and natural gas may be created when buried organic material is heated under pressure, then hydrocarbons migrate to the surface unless movement is blocked by impermeable layer of rock and molecules are trapped to form a petroleum reservoir - or unless the source rock is impervious, and gas/oil molecules never migrate until the source sediments are fractured ("fracked")

Source: US Geological Survey, National Assessment of Oil and Gas Fact Sheet - Natural Gas Production in the United States

Between 1967-73, the Federal government conducted three tests of nuclear weapons as part of Project Plowshare, to see if gas trapped in "tight formations" could be released by a massive explosion fracturing the bedrock. That approach was a failure, but hydrofracking technology for extracting unconventional gas has been commercially successful since 1997.

Fracking wells are drilled vertically like conventional wells, initially. About 500 feet above the tight sedimentary layer, however, the well head is redirected at an angle down to the gas-rich sediments and then drilled horizontally for as much as a mile further. The objective of directional drilling is to emplace as much pipe as possible into the formation where gas is trapped, rather than simply intercept the productive rock layer at just one point (the bottom of the well).

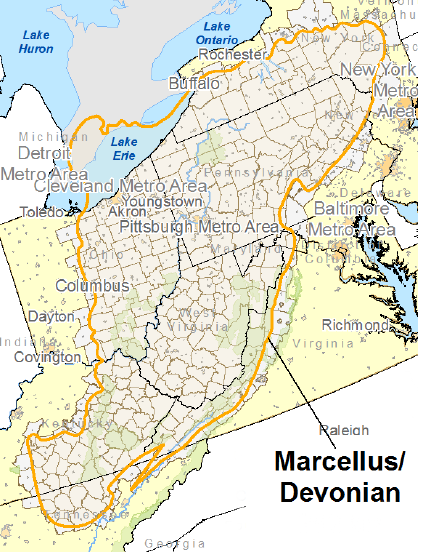

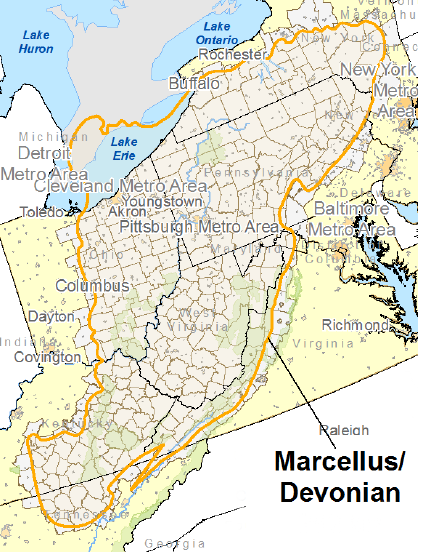

development of natural gas in the Marcellus Shale formation will increase supplies and lower prices, so gas could replace coal as the preferred source for fueling new industrial and utility generators

Source: US Department of Energy, Modern Shale Gas Development in the United States: A Primer, Marcellus Shale In The Appalachian Basin (Exhibit 19)

One in lace, the long length of horizontal pipe is punctured at many places by carefully-placed explosives lowered into the well. For horizontally-fractured wells, four million gallons of water may be pumped under high pressure into the pipe. The high water pressure escapes through the holes in the pipe, fractures the tight sediments, and creates paths for natural gas to flow back into the pipe. Sand grains or other particles added to the water intrude into the fractures while under pressure, propping open the fractures so the weight of overlying rock does not close the cracks.6

A cocktail of chemicals is also included to improve permeability and prevent bacteria from growing underground and blocking the artificially-created fractures. Wells may be "fracked" multiple times to maintain the pathways through the sediments to the tiny holes in the underground pipes.

horizontal drilling, with fracturing of thin layers of sediment, allows the extraction of commercial quantities of trapped gas

Source: Northern Territory (Australia) Department of Mines and Energy, How do we access Unconventional Gas?

Once the hydrofracking fluids ("produced waters") are pumped back out, gas flows into the well. Cement pumped in around the well bore blocks gas/fluids from leaking to the surface through the vertical section of the drilled hole, outside the pipe casing:7

- Production from "conventional" oil and gas resources requires having source rock with 1-2% OM [organic material], thermal maturity to transform the OM to oil and/or gas, and migration pathways to move the oil and/or gas to porous rocks that possess traps and seals to contain the material in reservoirs. These can be drilled vertically and produced economically.

- Shale gas development is "unconventional" in the sense that no porous reservoir, no migration, and no trap and seal are present. The gas is continuous throughout the highly-organic, thermally mature source rock. Thermal maturity generally is greater in the eastern parts of the Appalachian Basin, with "dry gas" (methane-rich, free of mobile liquids) to the east, and "wet gas" (methane plus ethane, propane, and other liquid hydrocarbons) to the west.

hydrocarbons may be extracted by conventional vertical wells, or unconventional horizontal drilling where rock layers rich in shale gas are fractured by pumping water underground under high pressure with particles ("proppants") to keep the fractures open

Source: Energy Information Administration, What is shale gas and why is it important? (modifying a US Geological Survey graphic)

Local/regional economic impacts associated with fracking and increased supply of natural gas include royalty payments to landowners, short-term employment at drilling pads, and increased sales by local businesses to support temporary drilling operations. National impacts include lower natural gas prices, reducing costs to consumers. Lower energy costs alone may not spur a manufacturing renaissance in the United States, but they certainly help.

Concerns about environmental impacts have spurred strong public opposition to expanding the use of hydrofracking. Inappropriate disposal of produced waters, which include the additives and chemicals used to increase gas flow underground, could pollute surface waters or aquifers if dumped inappropriately - and disposal via injection underground into deep wells in Ohio triggered earthquakes in late 2011. Since each drilling pad requires clearing 30 acres, and much of the surface above Marcellus Shale in the Chesapeake Bay watershed is forested, roughly 50-100,000 acres of forest could be cleared for drilling pads by 2030.8

coalbed methane is produced in many - but not all - coal fields

Source: Energy Information Administration, Coalbed Methane Fields, Lower 48 States

Like "tight gas," coalbed methane is "unconventional" gas - which is now called a "continuous" resource because the extraction of gas by fracking sediments is now common. Coalbed methane but is not "shale gas," because the source is coal rather than metamorphosed mud (shale).

In coal beds, methane molecules adhere to coal particles below the water table. If the groundwater is pumped away, however, the light methane molecules will migrate towards the surface.

In underground coal mines, water is drained and explosive methane seeps into mine tunnels. That methane is explosive, and a safety hazard to the miners. Expensive ventilation systems are required to minimize the methane in the mine, and the gas is vented to the surface as a waste product. Occasionally, failure to effectively purge the methane will trigger underground explosions that kill miners.

in 2013, active coalbed methane wells were concentrated in the Appalachian Plateau -

but some natural gas wells were located in the Valley and Ridge province in Lee County

Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Division of Oil and Gas Flexviewer page

Many coal beds are too thin or too deep for cost-effective mining. Some of the energy value in those coal seams can be recovered by lowering the water table in formations. Once the water barrier is removed, methane can then flow to wells drilled 500-1,500 feet deep into the coal, recovering the gas as a usable product.

The underground coal can be fractured, just like shale, to increase the amount of methane that flows to the well. In coal bed methane wells, nitrogen gas rather than water is used to create the pressure and stimulate fractures that can go as far as 400-500 feet into the coal formation; water would block gas flow. In Virginia, as little as 35,000 gallons of water may be required to fracture a coal bed methane well compared to up to 6,000,000 gallons for deeper conventional natural gas wells in the Marcellus Formation of Pennsylvania/New York.9

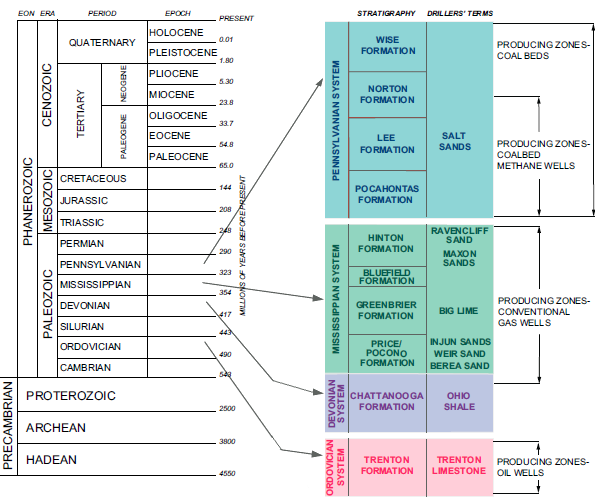

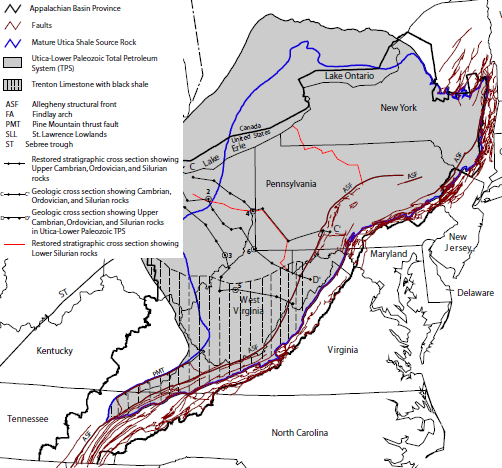

Devonian-age shales are older and deeper underground than the Pennsylvanian-age coal seams from which coalbed methane is extracted. The Marcellus, Utica, and other organic-rich shale layers are potentially-valuable sources of natural gas in Virginia, even though the cost to get molecules of shale gas to the surface is higher than the cost to produce coalbed methane.

generalized stratigraphic column showing productive intervals for oil, conventional gas, coalbed methane, and coal

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, (Figure 40)

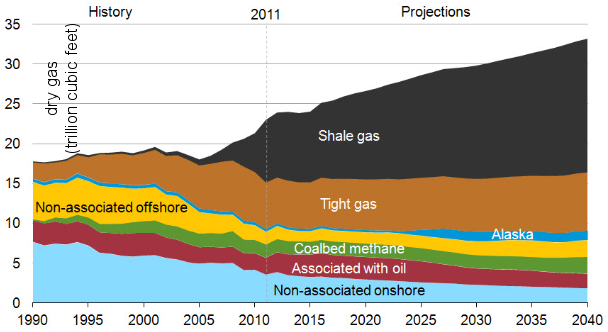

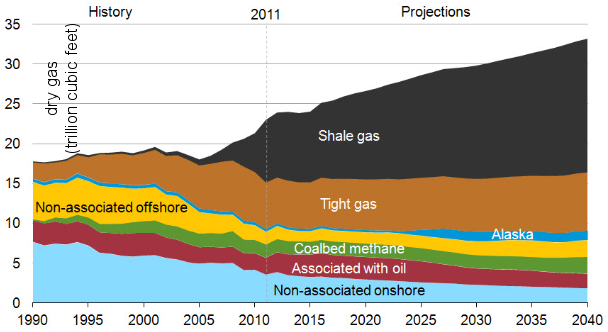

New technology that extracts shale gas is reshaping energy production in the Eastern United States. Projections of recoverable domestic energy resources, and expectations of how US industry will respond to long-term low-energy prices, have been revolutionized by the ability to recover massive amounts of natural gas trapped in shale formations through horizontal drilling and fracking.

Demand for sand, used for fracking, doubled between 2008-2013. That affected even the City of Hampton, far from the shale gas reservoirs in the Appalachians. Hampton had to pay a higher price for its Buckroe Beach sand replenishment project in 2013.10

projected 40-50% increase in supply of domestic natural gas could result in energy prices low enough

to increase manufacturing and transform US economy by 2040

Source: US Energy Information Administration, What is shale gas and why is it important? (December 5, 2012)

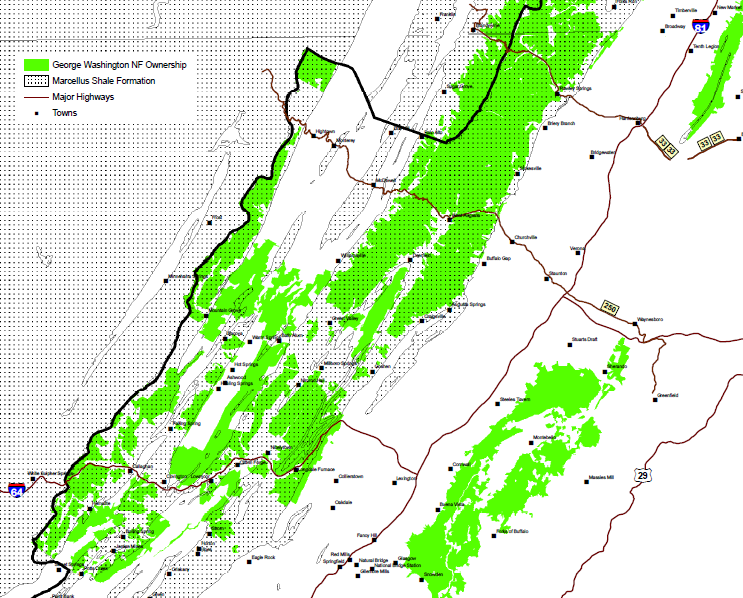

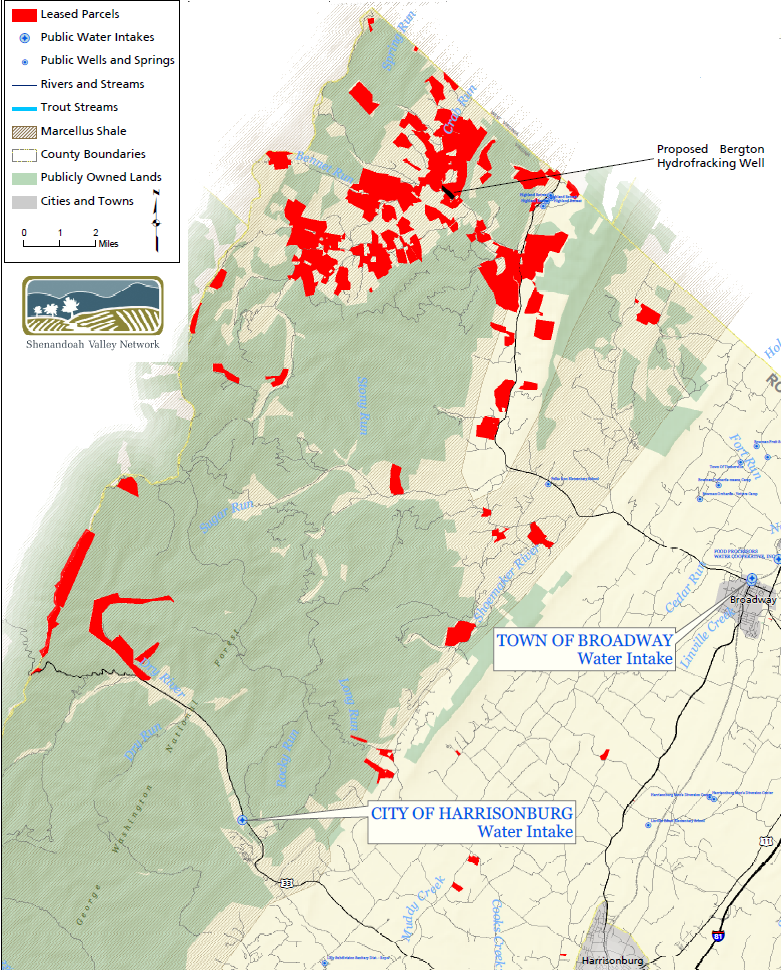

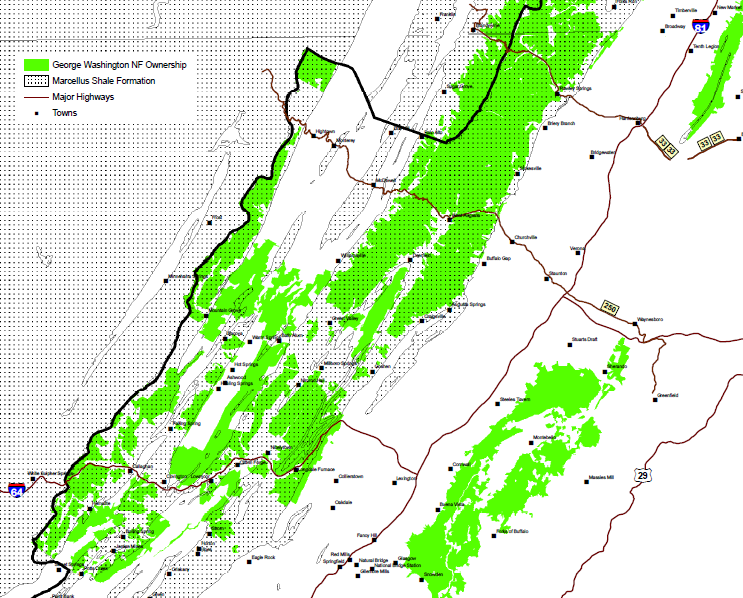

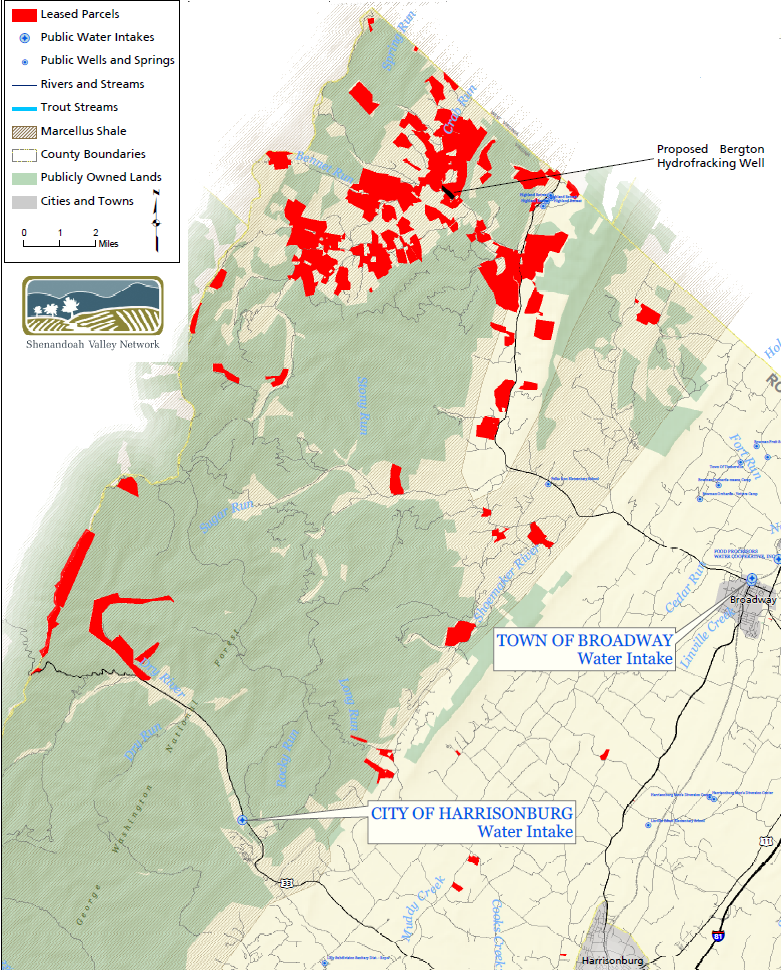

West Virginia, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York are the center of the Marcellus Shale natural gas boom, but there is potential in Virginia. The revision of the Forest Plan for the George Washington National Forest triggered debate over the potential impacts to water quality. The draft plan proposed in 2011 would have permitted fracking but would have banned horizontal drilling, blocking economic development of the gas resource. The draft received 54,000 comments, many focused on the fracking issue.11

much of the Marcellus Shale in Virginia lies beneath the George Washington National Forest (shaded green)

Source: US Forest Service, George Washington Forest Plan Revision

Rockingham County was the first jurisdiction in Virginia to use local zoning authority to hinder drilling for new gas wells within the county. Starting in 2006, various companies purchased leases from surface landowners; the leases authorized drilling and extraction of natural gas from underneath private land.

County supervisors responded to local concerns in 2010 by refusing to issue a permit to Carrizo Oil & Gas, Inc. for drilling a new natural gas well in Bergton, even though the area has a history of natural gas production. Over a dozen wells have been drilled there, and natural gas from Devonian-age formations was produced commercially between 1982-86.12

Production from the Bergton field occurred before the fracking boom, and before concerns emerged that surface waters could be contaminated by improper disposal of waters recovered from a fracked well. As one Rockingham County supervisor noted, in thoughts that would be echoed by Pittsylvania County officials two years later when considering uranium mining:13

- You don't trade clean water for dollars... How do you un-contaminate water once it's been contaminated?

Devonian sediments with natural gas potential are located in Virginia, but the Marcellus Shale layers are relatively thin compared to other states

Source: US Geological Survey, Assessment of Undiscovered Natural Gas Resources in Devonian Black Shales, Appalachian Basin, Eastern U.S.A. (Open-File Report 2005-1268)

In 2013, Carrizo confirmed that it would allow its leases to expire without renewal, and all rights for drilling would terminate. Recent production from Marcellus Shale formations had lowered the value of any potential gas field, and Carrizo had not found commercial quantities of gas after drilling a well into similar thin, highly faulted formations in Hardy County (West Virginia). Though there is natural gas underneath Rockingham County, there was no economic reason to extract it so long as the production costs were too high to sell the gas at a profit.14

location of natural gas leases in Rockingham County

Source: Community Alliance for Preservation, Marcellus Shale Leases in Rockingham County (original map from Piedmont Environmental Council)

There are more natural gas resources to be discovered and developed. Virginia is within two "plays," a term used for hydrocarbon exploration opportunities.

The Southern Appalachian Sub-thrust Sheet Play is based on the hypothesis that thrust faults - created as island arcs and finally as Africa collided into Virginia - could have trapped hydrocarbons originally deposited in Paleozoic sediments.

Thrust faults in the Rocky Mountains created oil and gas reservoirs which are now tapped by producing wells. Similar geological formations on the East Coast may be viable targets for extracting natural gas trapped underneath thrust sheets in the Valley and Ridge, Blue Ridge, and Piedmont physiographic provinces. It is possible that hydrocarbons that formed in limestones, shales, and sandstones deposited in the Neoacadian orogeny could have migrated to reservoir rocks sealed off by thrust sheets pushed from the east during the Alleghenian orogeny.

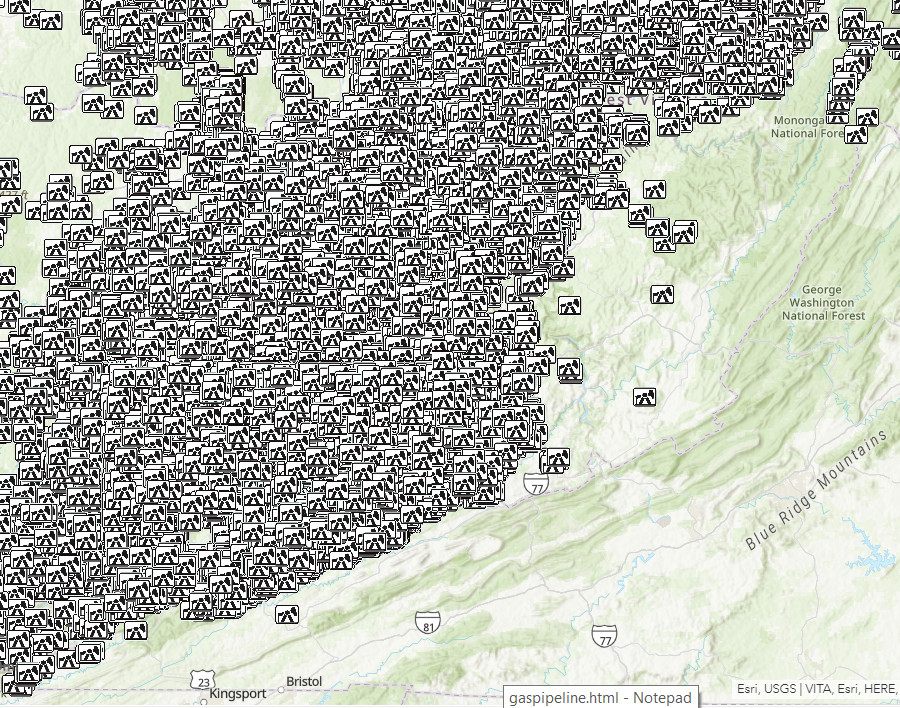

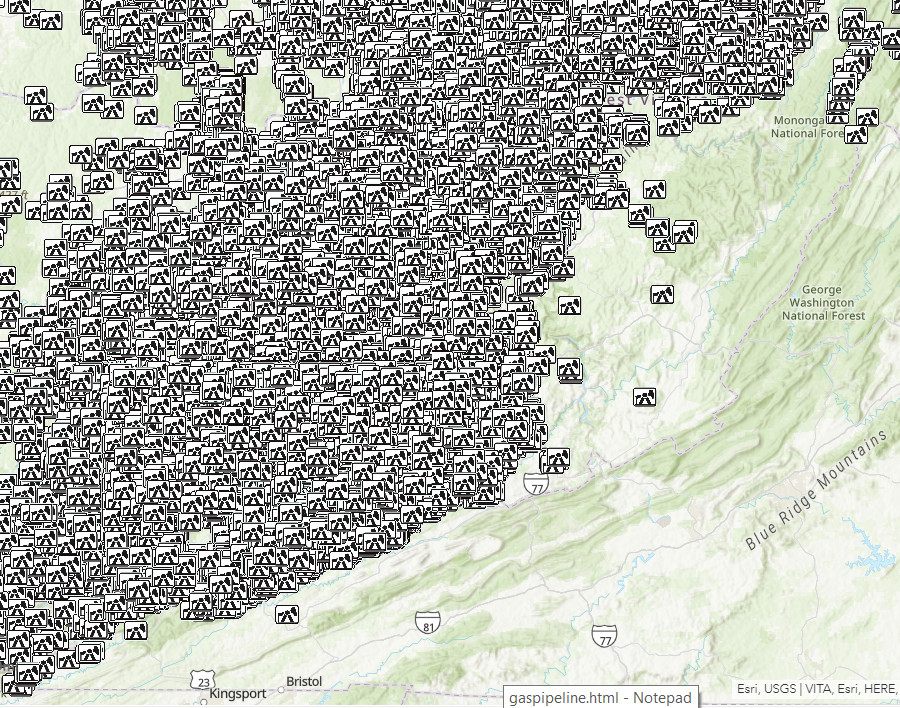

oil and gas wells are concentrated in sedimentary formations west of Virginia, except there are methane wells in Virginia's coal fields

Source: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), EnviroMapper

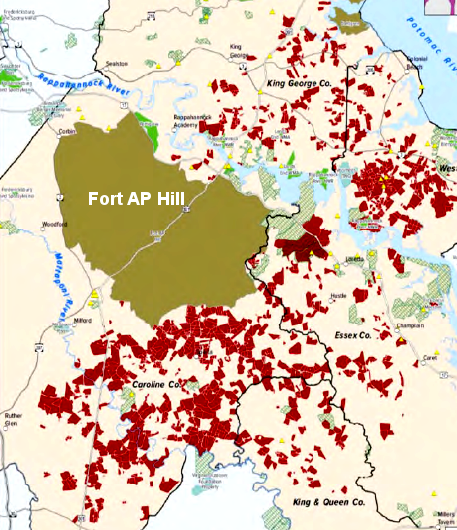

In 2014, after a year-long debate, the supervisors in Washington County authorized drilling for natural gas throughout the county's agricultural zones. Exploration has focused on the land near the boundary of the Valley and Ridge and Appalachian Plateau, and each new well will need to be approved through a special exception permit. In 2015, King George County also chose to require special exception permits rather than try to use local zoning to ban fracking in the Taylorsville basin, but made clear that drillers would find it difficult to obtain county approval for the permits.15

Devonian sediments deposited by erosion during/after the Acadian orogeny include organic material that decomposes into natural gas

Source: US Geological Survey, Assessment of Undiscovered Natural Gas Resources in Devonian Black Shales, Appalachian Basin, Eastern U.S.A. (Open-File Report 2005-1268)

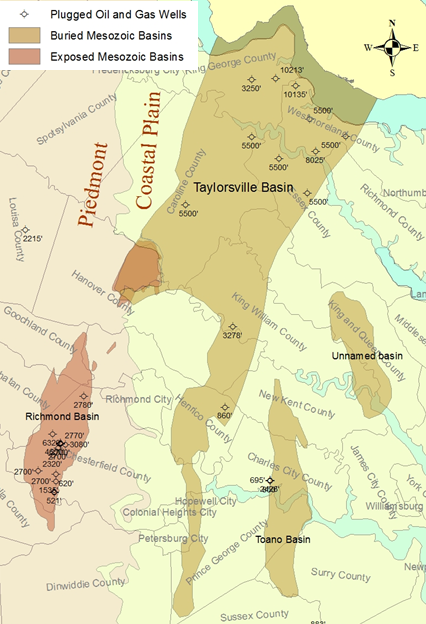

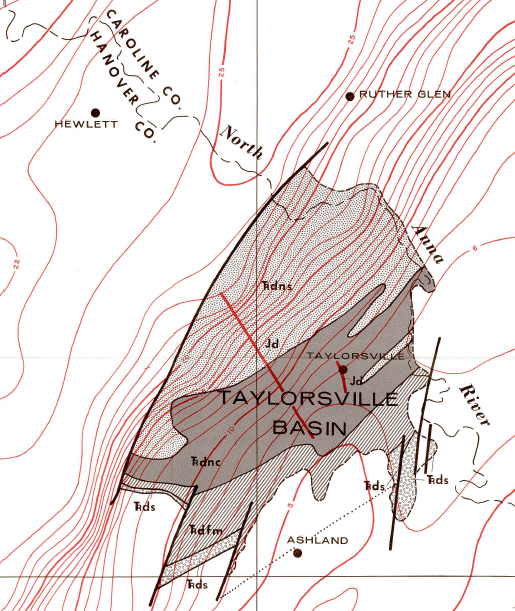

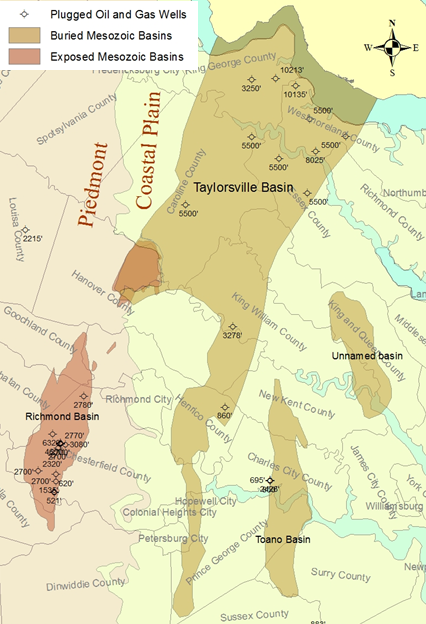

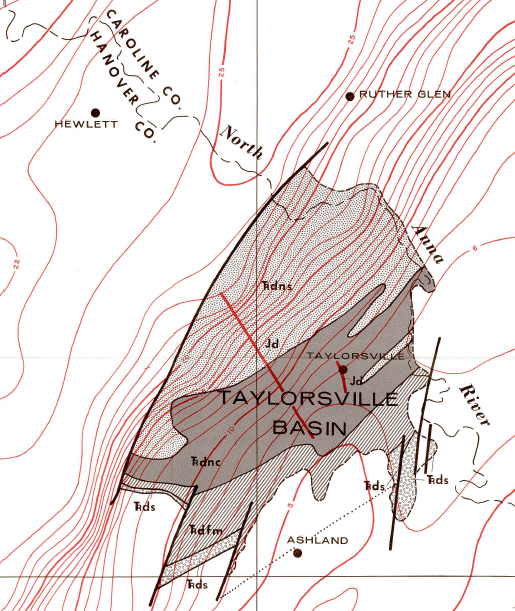

The East Coast Mesozoic Basins Play speculates that younger Triassic basins, which formed when the Atlantic Ocean opened, hold commercial quantities of hydrocarbons as natural gas.

Coal beds near Richmond prove that Triassic sediments included organic material. Drilling in the Taylorsville Basin in 1968 and then in 1986 found hydrocarbons at depths between 1,182' to 5,454' - but not enough oil and gas to justify developing the resource. Exploratory drilling in the Richmond and Taylorsville basins showed that faults have disrupted the sediments, and no commercial quantities of coalbed methane were identified. As described by the Bureau of Land Management:16

- The Richmond Basin, Virginia, has been drilled extensively for coal, oil, and gas. Between 1897 and 1985, 38 exploratory holes were drilled in the basin. Of the 38 holes... 6 had shows of liquid and/or gaseous hydrocarbons... Extensive drilling in this relatively small basin indicates that the chances of finding significant amounts oil or gas there are likely minimal.

In 1989-90, drilling in the Richmond basin revealed coalbed methane between 1,200-3,000 feet deep. The Richmond basin itself extends down to 7,100 feet, while the Taylorsville basin to the north is 9,900 feet deep and two presumed Mesozoic basins on the Outer Continental Shelf may be up to 13,000 feet deep.

Faulting limits commercial potential for coalbed methane extraction and there may be no conventional traps remaining to capture natural gas generated by heat/pressure, but the volume of source rocks could be suitable for commercial development by fracking. Between 1995-2012, the US Geological Survey revised its assessment of technically recoverable, but still-undiscovered oil and gas resources of the Mesozoic basins on the East Coast.

Triassic basins are potential hydrocarbon reservoirs

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy, Hydraulic Fracturing in Virginia

By considering unconventional development technology (fracking), the Federal agency increased its estimate from 350 billion cubic feet of natural gas in 1995 to 3,860 billion cubic feet in 2012, more than ten times the previous total. The 2012 estimate included 850 billion cubic feet that might be located in Virginia.17

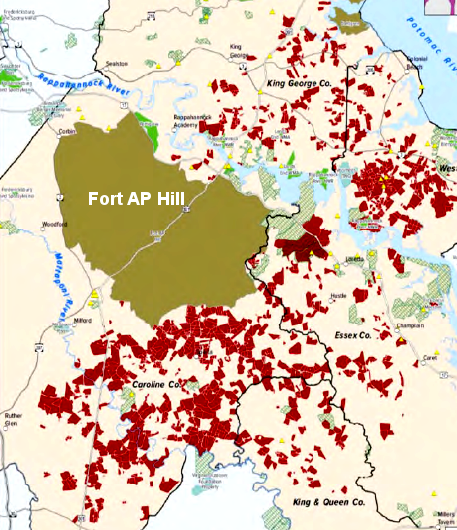

By 2014, a Dallas-based company had purchased 84,000 acres of leases in the Taylorsville Basin. The company reassured King George County residents that it would use nitrogen rather than water during any fracking of the underground formations to release natural gas, and the gas technology would reduce some of the impacts of heavy trucks that damage local roads.

natural gas leases in the Taylorsville Basin

Source: King George County, King George County Fracking 101

However, the company with the leases planned to sell them to someone else, rather than drill exploratory wells. If there are commercial quantities of natural gas in the Taylorsville Basin, the extraction technology will be determined by the final company that purchases the mineral rights.18

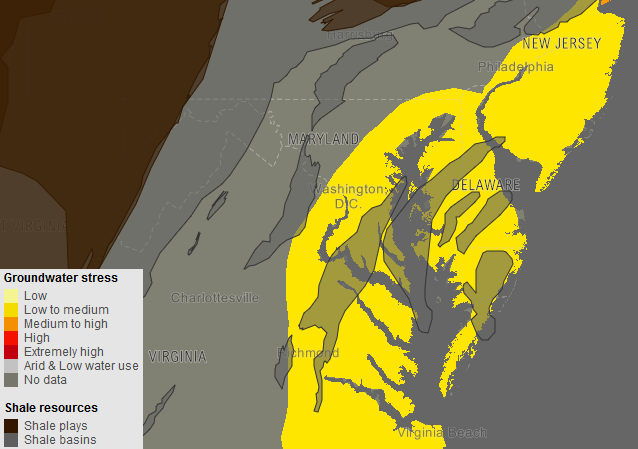

One concern regarding development of natural gas resources is the potential that surface streams or groundwater wells would be affected. Groundwater could be depleted if fracking extracts water from local aquifers. The Northern Neck Planning District Commission's executive director commented about the potential negative impacts of extracting natural gas, saying that the area's economy was dependent upon "farming, fishing, forestry and fun" and "tourism doesn't start with an 'F.'"19

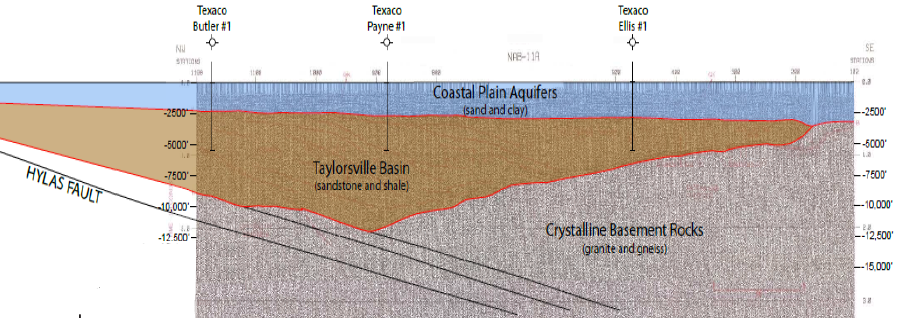

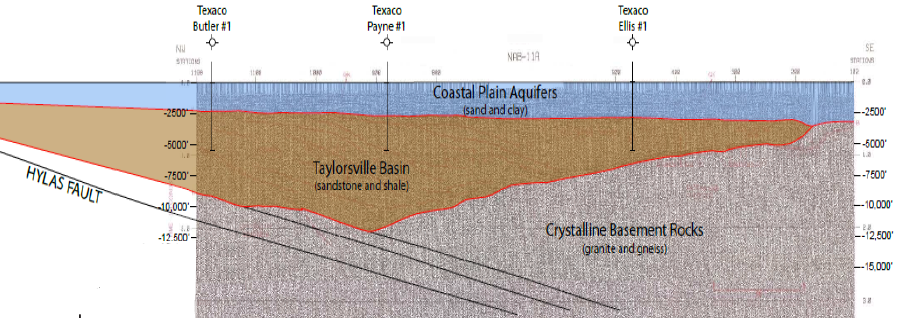

only the southern portion of the Taylorsville Basin is exposed at the surface; the potential gas-producing sediments underneath the Northern Neck are buried below more-recent deposits

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Simple Bouguer gravity anomaly map of the Richmond and Taylorsville basins and vicinity, Virginia (Publication 053)

The movie Gasland highlighted a home where tap water could catch fire due to methane contaminating a drinking water well. That possibility has triggered fears on the Northern Neck that groundwater aquifers could be affected by hydraulic fracturing to release "tight gas." Surface streams and groundwater could be contaminated from drilling muds and fracking fluids if they leak through the cement around the well casing, or through combinations of artificial/natural fractures that create pathways for methane to migrate upward into drinking water aquifers.

Most homeowner wells are less than 500 feet deep, and only a few municipal/industrial wells go as deep as 2,000 feet. Because the usable part of the freshwater aquifer underneath the Coastal Plain stops at around 2,500 feet, state regulations require all oil/gas wells in Tidewater to be cased and cemented to that depth.20

Most of the gas-rich shale in the basin may lie below the freshwater aquifer, but new vertical fractures are created in modern drilling ("fracking") that could reach up to the aquifer. New cracks created by fracking are intended to intercept just tens/hundreds of feet of gas-bearing geologic formations, but could intercept existing cracks that lead to the surface. Also, earthquakes comparable to the magnitude 5.2 quake centered in Louisa County in 2001 could affect how fluids migrate underground.

Artificial fracking in the Marcellus shale has created fractures as much as 2,000' long. To reduce the risk that a new well might create a new fracture damaging a gas storage field, in 2011 Dominion Transmission obtained a protective buffer zone banning drilling within 2,000' of the storage field in New York. Natural fractures in sedimentary rocks may exceed 3000' in length, and gas/fluids could migrate between new artificial cracks and pre-existing natural cracks. A decision on the safe vertical separation between fracked zones and overlying aquifers depends upon the local geology.21

wells drilled in the Taylorsville Basin have penetrated through the Coastal Plain aquifer into the Triassic sediments below 5,000' to reach potential hydrocarbon resources

Source: Virginia Department on Mines, Minerals and Energy, Taylorsville Basin - Potential for Undiscovered Natural Gas Resources?

Local governments such as King George County fear the Potomac Aquifer is becoming stressed, with artificial withdrawals of groundwater for public water supplies and crop irrigation exceeding natural recharge of the aquifer. Fracking for natural gas extraction in the Taylorsville Basin would increase groundwater withdrawals, since millions of gallons of water are used during the initial drilling and fracturing stages.

Oil and gas drilling is regulated by the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy (DMME). Local officials have feared that fracking operations might be exempted from the groundwater withdrawal permits required in the Eastern Virginia Groundwater Management Area by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ).

If fracking in the Taylorsville Basin relied upon nitrogen gas, as in the coal fields of southwestern Virginia, then pollution controls required to restore the water quality in the Chesapeake Bay could become a factor. Northern Neck counties must reduce nitrogen runoff into the bay in order to meet the Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) for that nutrient. If wells were fracked with nitrogen, and Virginia still adhered to its Watershed Implementation Plan commitments to reduce nitrogen runoff so the bay can ultimately meet Clean Water Act standards, then Northern Neck farmers might be required to implement stricter controls on their use of nitrogen-rich fertilizer.

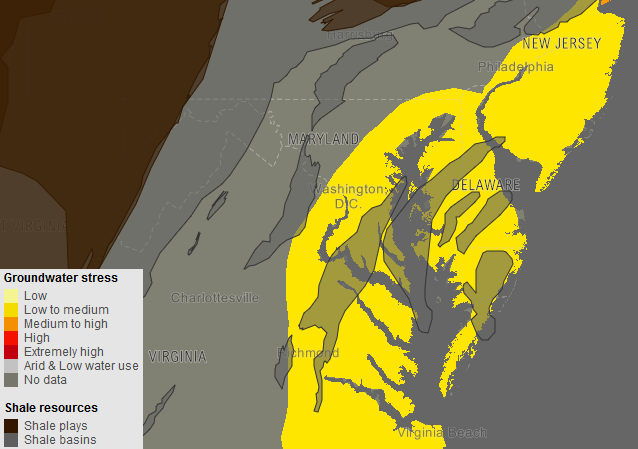

local governments in the Northern Neck and Middle Peninsula fear the Potomac Aquifer is becoming stressed (artificial withdrawals exceed natural recharge), and fracking in the Taylorsville Basin might increase groundwater withdrawals substantially

Source: World Resources Institute, Shale Resources and Water Risks

In 2016, King George County adopted a zoning ordinance with setback requirements for wells that effectively limited oil and gas drilling to just 9% of the county. In 2017, Augusta County completely prohibited fracking, but continued to allow traditional drilling of wells for petroleum resources. There was no known hydrocarbon potential in that county, and the ban on fracking was triggered by opposition to construction of the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline through Augusta County.22

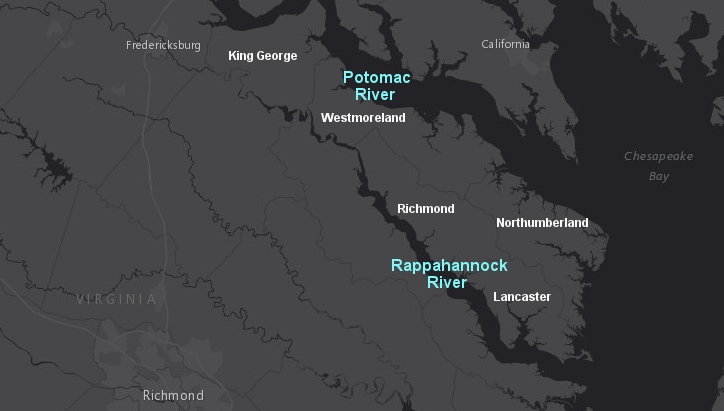

Later in 2017, the Board of Supervisors in Richmond County voted unanimously to ban oil and gas drilling. Only a tiny portion of that county lies within the Taylorsville Basin, and no land there had been leased for natural gas exploration. Threats of legal action by the Virginia Petroleum Council were successful in getting the supervisors in nearby Westmoreland County to delay a decision on banning or restricting fracking.23

The 2020 General Assembly ended the potential extraction of natural gas resources from the Taylorsville Basin sediments. The legislature prohibited hydraulic fracturing in the Eastern Virginia Ground Water Management Area, which completely encompassed the area of interest.24`

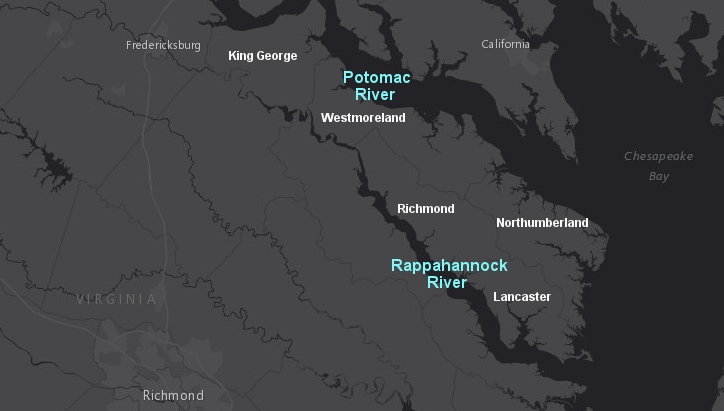

King George, Westmoreland, and Richmond counties have considered banning or limiting where oil and gas drilling can occur

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

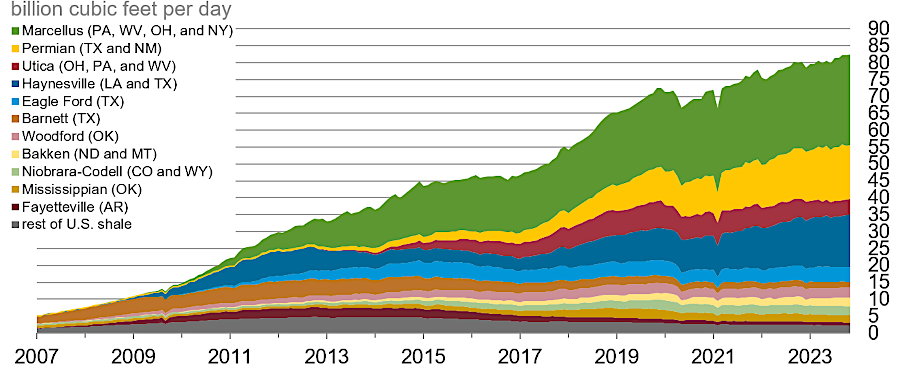

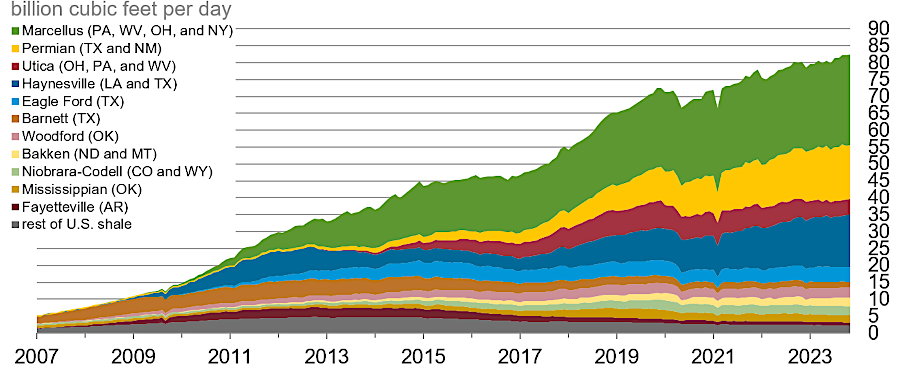

by 2023, the Marcellus shale play was producing the largest amount of natural gas in the United States

Source: US Energy Information Administration, Natural gas explained

Links

natural gas well VC-537232 on McClure River in Dickenson County

oil and gas fields in Virginia, including Nora coalbed methane field, and pipelines carrying gas to market

Source: Virginia Center for Coal and Energy Research - Virginia Energy Patterns and Trends

References

1. "Burning Springs," West Virginia Encyclopedia, http://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/725 (last checked December 26, 2011)

2. J.W. Huddle, Eloise T. Jacobsen, A.D. Williamson, "Oil And Gas Wells Drilled In Southwestern Virginia Before 1950," Geological Survey Bulletin 1027-L, United States Geological Survey, 1956, p.501, p.531, http://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1027l/report.pdf (last checked July 8, 2013)

3. "Virginia - Reasonably Foreseeable Development Scenario For Fluid Minerals," Bureau of Land Management, May 2008, pp.15-16, http://www.blm.gov/pgdata/etc/medialib/blm/es/jackson_field_office/planning/planning_pdf_va_rfds.Par.20335.File.dat/Virginia_RFDS_R5.pdf; "Virginia's burning question," Virginia Business, June 28, 2012, http://www.virginiabusiness.com/index.php/news/article/virginias-burning-question/320083/ (last checked December 28, 2012)

4. "Coalbed Methane in Virginia," Virginia Natural Gas Facts, http://vanatgasfacts.org/coalbed-methane.html (last checked January 1, 2013)

5. "Reasonably Foreseeable Development Scenario For Oil And Gas For The George Washington National Forest Virginia And West Virginia," Appendix K in "Forest Plan Revision - George Washington National Forest," US Forest Service, June 2012, K-2, Final Environmental Impact Statement (last checked September 2, 2016)

6. "Executive Summary - Assessment of the Potential Impacts of Hydraulic Fracturing for Oil and Gas on Drinking Water Resources (DRAFT)," Environmental Protection Agency, June 2015, http://ofmpub.epa.gov/eims/eimscomm.getfile?p_download_id=523326 (last checked July 14, 2015)

7. "Exploring the Environmental Effects of Shale Gas Development in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed," Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee Workshop Report, STAC Publication 13-01, February, 2013, p.7 http://www.chesapeake.org/pubs/297_Gottschalk2013.pdf; "Modern Shale Gas Development in the United States: A Primer," US Department of Energy, April 2009, p.ES-4, http://www.netl.doe.gov/technologies/oil-gas/publications/EPreports/Shale_Gas_Primer_2009.pdf (last checked August 2, 2013)

8. "Ohio Earthquake Likely Caused by Fracking Wastewater," Scientific American, January 4, 2012, http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=ohio-earthquake-likely-caused-by-fracking; "Exploring the Environmental Effects of Shale Gas Development in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed," Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee Workshop Report, STAC Publication 13-01, February, 2013, p.11 http://www.chesapeake.org/pubs/297_Gottschalk2013.pdf (last checked April 8, 2013)

9. "Hydraulic Fracturing in Virginia and the Marcellus Shale Formation," Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy, http://www.dmme.virginia.gov/DGO/documents/HydraulicFracturing.shtml (last checked January 1, 2013)

10. "The new boom: Shale gas fueling an American industrial revival," The Washington Post, November 14, 2012, http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2012-11-14/business/35506130_1_natural-gas-shale-cf-industries; "Buckroe Beach replenishment: Cost of sand increases with demand," Daily Press, September 2, 2013, http://www.dailypress.com/news/hampton/dp-nws-hampton-beach-restoration-20130902,0,3706979.story (last checked September 4, 2013)

11. "George Washington National Forest - Draft Revised Land and Resource Management Plan," US Forest Service, April 2011, p.3-14, http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5297819.pdf; "Fracking: a topic of intense debate," The Roanoke Times, August 14, 2012, http://www.roanoke.com/news/roanoke/wb/312766 (last checked January 1, 2013)

12. "Virginia - Reasonably Foreseeable Development Scenario For Fluid Minerals," Bureau of Land Management, May 2008, pp.21-22, http://www.blm.gov/pgdata/etc/medialib/blm/es/jackson_field_office/planning/planning_pdf_va_rfds.Par.20335.File.dat/Virginia_RFDS_R5.pdf (last checked January 1, 2013)

13. "Wastewater Becomes Issue in Debate on Gas Drilling," New York Times, May 3, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/04/nyregion/wastewater-is-an-issue-in-hydrofracking.html?_r=0; "A Year Later, The Prospect of Fracking Remains," hburgnews.com, March 21, 2011, http://hburgnews.com/2011/03/21/a-year-later-the-prospect-of-fracking-remains/; "Virginia - Reasonably Foreseeable Development Scenario For Fluid Minerals," Bureau of Land Management, May 2008, pp.21-22 (last checked January 1, 2013)

14. "Carrizo Abandoning All Its Private Oil & Gas Leases in Rockingham County," Old South High (Harrisonburg, VA blog), May 6, 2013, http://www.oldsouthhigh.com/2013/05/06/carrizo-abandoning-all-its-private-oil-gas-leases-in-rockingham-county/; "Drilling Company Moves On," Daily News-Record, May 8, 2013, http://www.dnronline.com/article/drilling_company_moves_on(last checked May 8, 2013)

15. "Virginia - Reasonably Foreseeable Development Scenario For Fluid Minerals," Bureau of Land Management, May 2008, p.11; "Washington County supervisors vote 6-1 to allow natural gas drilling," Bristol Herald-Courier, September 10, 2014, http://www.tricities.com/news/local/article_4ea78bae-38a2-11e4-856e-0017a43b2370.html; "King George decides to control fracking through strict zoning ordinance," Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star, January 21, 2015, http://www.fredericksburg.com/news/local/king_george/king-george-decides-to-control-fracking-through-strict-zoning-ordinance/article_bbdb50ac-c223-526d-b1b5-a24c175ed690.html (last checked January 28, 2015)

16. "Virginia - Reasonably Foreseeable Development Scenario For Fluid Minerals," Bureau of Land Management, May 2008, p.13; William Lassetter, "Taylorsville Basin - Potential for Undiscovered Natural Gas Resources?," Virginia Department on Mines, Minerals and Energy, presentation to King George County Community Meeting, June 12, 2014, http://www.king-george.va.us/component/option,com_docman/Itemid,0/task,doc_download/gid,2930/ (last checked September 23, 2014)

17. Catherine B. Enomoto, "Energy Resource Potential Of The Mesozoic Basins In Virginia," Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy Open File Report 2013-01, p.4-8, http://www.dmme.virginia.gov/commercedocs/OFR_13_01.pdf (last checked April 16, 2014)

18. "Fracking: Shore Aims To Flip Gas Drilling Leases," Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star, April 15, 2014, http://news.fredericksburg.com/newsdesk/2014/04/15/fracking-shore-aims-to-flip-gas-drilling-leases/ (last checked April 16, 2014)

19. "Fracking: What it could mean for Westmoreland," Westmoreland Times, September 6, 2014 , http://www.westmorelandnews.net/?p=9222 (last checked September 9, 2014)

20. David Spears, "Hydraulic Fracturing for Natural Gas in Virginia," Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy, July 9, 2014 for Virginia Master Naturalists, http://www.virginiamasternaturalist.org/continuing-education.html (last checked July 10, 2014)

21. "The Truth About Fracking," Scientific American, November 2011, http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-truth-about-fracking/; "Dominion Transmission, Inc. Docket No. CP11-493-000," Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, November 17, 2011, http://www.ferc.gov/whats-new/comm-meet/2011/111711/C-2.pdf; Richard J. Davies, Gillian R. Foulger, Simon Mathias, Jennifer Moss, Steinar Hustoft, Leo Newport, "Comment on Davies et al., 2012 - Hydraulic fractures: How far can they go?," Marine and Petroleum Geology, May 2013, Volume 43 (May 2013), Pages 519-521, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2013.02.001; "Safe distance between hydraulic fractures and groundwater," Shale Gas Information Platform, October 7, 2012, http://www.shale-gas-information-platform.org/areas/news/detail/article/safe-distance-between-hydraulic-fractures-and-groundwater.html (last checked October 20, 2014)

22. "Augusta first county in Va. to ban fracking," News Leader, February 23, 2017, http://www.newsleader.com/story/news/local/2017/02/23/augusta-first-county-va-ban-fracking/98304310/; "King George adopts strict regulations regarding fracking," Free Lance-Star, August 16, 2016, http://www.fredericksburg.com/news/local/king_george/king-george-adopts-strict-regulations-regarding-fracking/article_305d294b-0a38-5441-a4ec-36ac767b3a24.html (last checked November 14, 2017)

23. "Richmond County becomes second locality in state to ban fracking," Free Lance-Star, November 14, 2017, http://www.fredericksburg.com/news/richmond-county-becomes-second-locality-in-state-to-ban-fracking/article_2b805bce-d7c5-54d7-aad6-50c282c4425c.html (last checked November 14, 2017)

24. Senate Bill No. 106 (SB 106), Virginia General Assembly, 2020, https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?201+ful+SB106ES1 (last checked March 14, 2020)

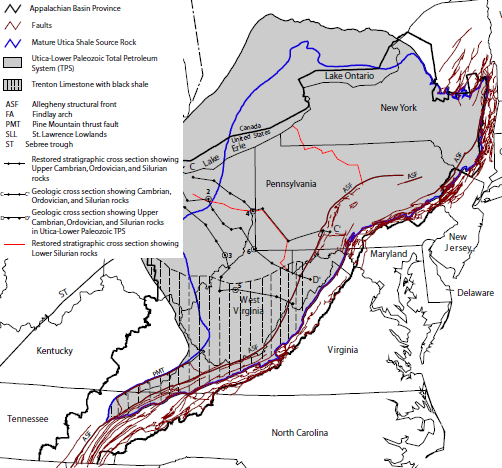

Appalachian basin and the Utica-Lower Paleozoic Total Petroleum System (shale formations with tight gas are primarily outside of Virginia)

Source: US Geological Survey, Assessment of Appalachian Basin Oil and Gas Resources: Utica-Lower Paleozoic Total Petroleum System

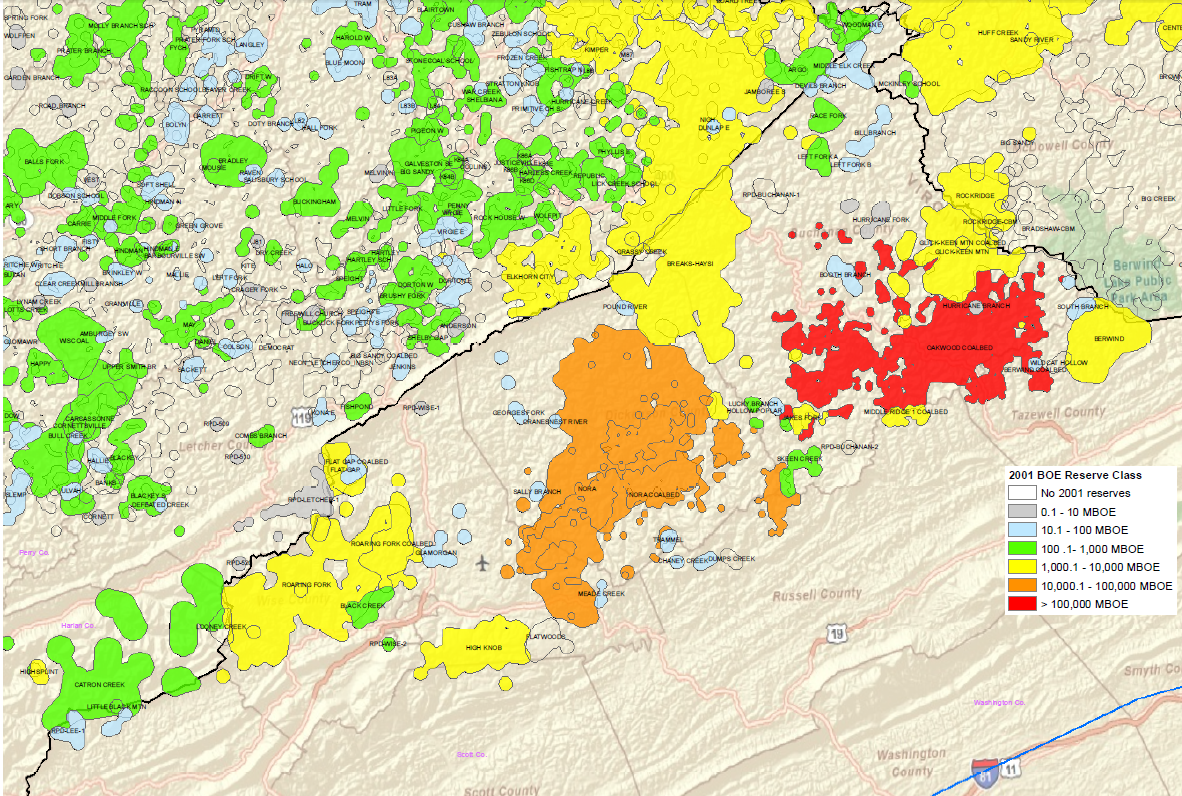

barrel-of-oil equivalent (BOE) of the known oil and gas fields in the Appalachian Basin in 2001

Source: US Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, Detailed Oil and Gas Field Maps

Rocks and Ridges - The Geology of Virginia

Energy in Virginia

Virginia Places