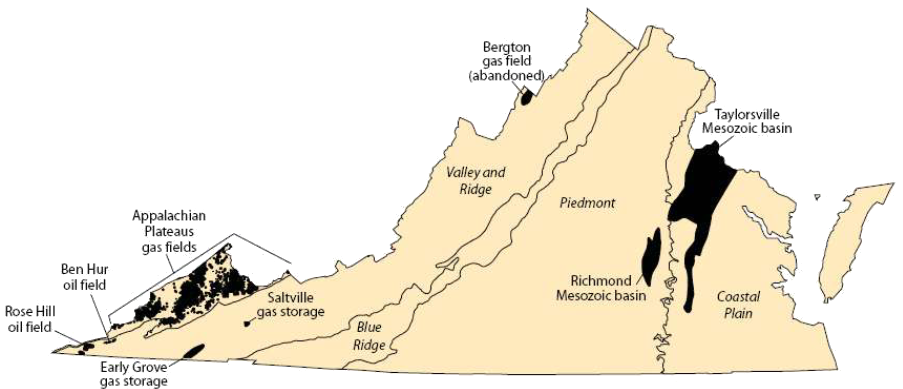

oil and gas fields in Virginia

Source: Virginia Center for Coal and Energy Research - Virginia Energy Patterns and Trends

oil and gas fields in Virginia

Source: Virginia Center for Coal and Energy Research - Virginia Energy Patterns and Trends

Virginia has known reservoirs of both oil and natural gas west of the Blue Ridge. In addition, there may be undiscovered petroleum resources in Upper Devonian black shales underneath Paleozoic thrust sheets (comparable to producing fields in east-central Kentucky), in Triassic basins east of the Blue Ridge, and in Triassic basins and other sediments underneath the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS).

Most speculation is associated with the offshore potential in areas which could be leased by the Federal government. Efforts to find onshore oil in Virginia are minimal; resource management conflicts involving new oil fields in Virginia will involve impacts on the Outer Continental Shelf and development of support operations in places such as Cape Charles.

Virginia's known oil resources are in Paleozoic sediments. In the Cambrian and Ordovician Periods, Virginia was at the edge of the North American continent - and underwater. Shales rich in organic matter and layers of limestone accumulated at the bottom of a shallow offshore basin 550-450 million years ago.

Sediments accumulated for million of years, with limestones forming when sea levels were higher and shales during periods of low water, especially in advance of the Taconic and Avalon orogenies. Different types of sediments formed as conditions changed, which geologists note by labeling distinct rock formations that were created under similar conditions. The length of time and rate of sediment accumulation affect the width of formations, which can vary widely. For example, in Lee County the Conasauga Shale is 500-550 feet thick, while the Rome Formation is 1,600 feet thick.1

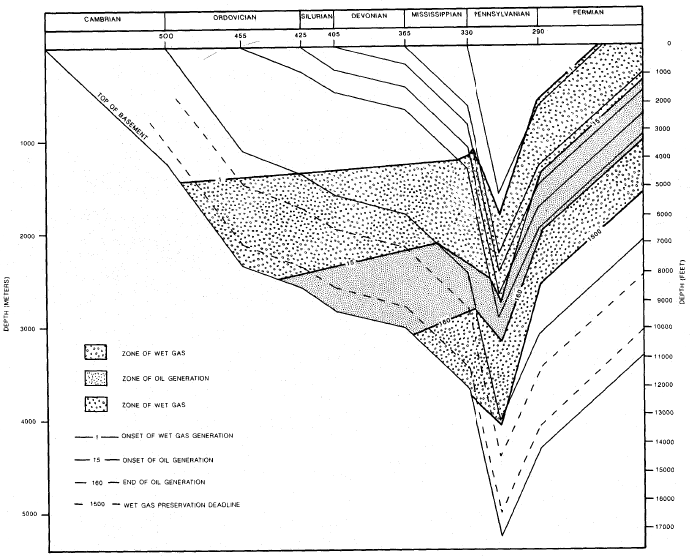

The organic matter in the shales of western Virginia were cooked by heat/pressure from overlying sediments deposited in the Silurian, Devonian, and later periods. Carbohydrates/lipids/proteins in the sediments broke apart, and some of the molecules reorganized into biopolymers called kerogen. When the kerogen was baked by the right combination of heat and pressure, kerogen converted into oil and gas in a process called diagenesis.

looking for oil shale on Butt Mountain, west of Blacksburg

known and potential oil and gas fields in Virginia

Source: Bureau of Land Management, Virginia - Reasonably Foreseeable Development Scenario For Fluid Minerals (Figure 8)

The "window" for conversion of kerogen into oil involves temperatures between 150-300°F (usually between 7,000-18,000 feet deep), roughly the temperature of boiling water. The window for conversion into natural gas involves temperatures higher than 300°F. There is no ignition source, so the petroleum does not burn.

Hydrocarbons are light and fluid, so they migrate upward after diagenesis. Hydrocarbons escape at the surface, but in some cases the oil and gas is trapped by overlying impervious rock layers or in porous sandstone/limestone formations.2

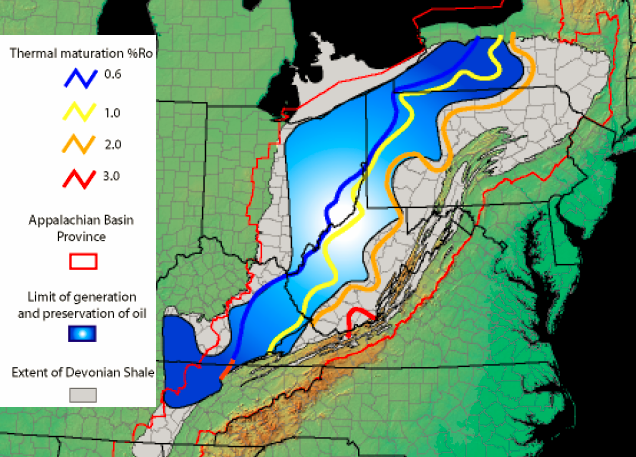

sediments with potential for liquid oil are west of Virginia, where pressure from overlying deposits and tectonic movements were lower

Source: US Geological Survey, Assessment of Undiscovered Natural Gas Resources in Devonian Black Shales, Appalachian Basin, Eastern U.S.A. (Open-File Report 2005-1268)

In Lee County, where Virginia's only two commercial oil fields are located, geologic faults in the Trenton Limestone blocked some of the oil that was migrating from the original shales. The fractured rock trapped oil in isolated underground reservoirs until wells drilled in the last century pierced the traps.

At the moment, Lee County is the only place in Virginia where pressure and temperature are known to have been high enough to convert organic sediments into oil (but not hot enough to bake the oil into natural gas) in commercial quantities. However, oil is produced from other wells by condensing fluids in natural gas.

oil production sites in Virginia in 2006, including condensates from gas wells

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy - Oil

The first well that produced oil for use in the United States was drilled in Noble County, Ohio. The Thorla-McKee well was drilled in 1814 to produce brine that would be boiled down to make salt. Rather than waste the oil which contaminated the brine, Silas Thorla and Robert McKee used cloth to absorb it and then resold the oil for medicinal use. Not until 1849 did Edwin Drake intentionally drill for oil in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

Virginia's first oil wells were developed in what is now West Virginia, along the Kanawha River. In 1860, wells were drilled in Wirt County near a "burning spring," where natural gas seeped from the ground and occasionally caught fire. The original objective of drilling in that area was to produce saline water, to be boiled to create salt, but the brine was so contaminated with "rock oil" that landowners shifted to drilling for petroleum. The Burning Springs Oil Field became part of West Virginia in 1863.3

In Lee County, surface oil seeps (where liquid petroleum leaks to the surface) alerted people to the presence of hydrocarbons. Drilling started in 1910, after a farmer reportedly:4

The Rose Hill field did not open until 1942, when demand was high during World War II. The B. C. Fugate #1 well was drilled 1,115 feet deep, and was the first commercially productive oil well in Virginia. It initially produced 60 barrels/day, but flow soon declined to eight barrels/day. The crude oil was trucked to Middlesboro, KY, then sent by train to refineries in Charleston, WV.5

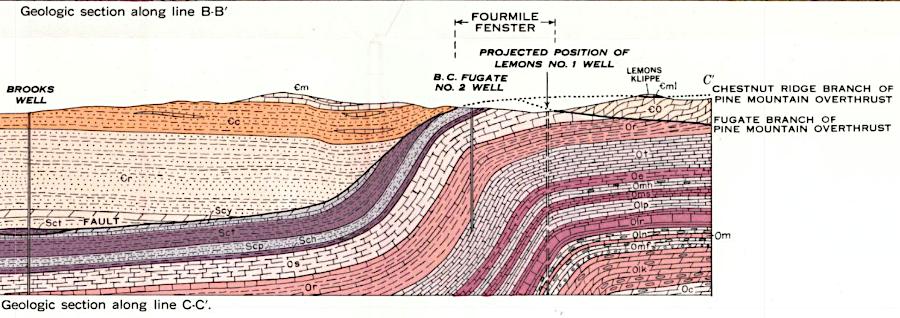

oil wells in Lee County were drilled into formations deposited in the Ordovician Period

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Economic Development, Geologic Map and Structure Sections of the Rose Hill District, Lee County, Virginia and Hancock and Claiborne Counties, Tennessee (1952) (from University of Alabama Library)

The Ben Hur field was developed in 1963, and expanded to Fleenortown two miles away in 1981. Original oil wells ranged in depth from 1,110 feet to 2,550 feet. Both oil fields are located in a "fenster" or window where erosion has removed the overlying Pine Thrust block, exposing the Bales block underneath. The oil was formed before tectonic pressure pushed the Pine Thrust block over the Bales block of limestone, and has since migrated into fractures formed by the tectonic stresses when Africa collided with North America.

The oil in those two fields comes from a 400-500 foot thick reservoir in the Trenton Limestone, where the oil was trapped. The US Geological Survey reported in 1954:6

The source rocks include organic sediments in the Rome Formation, which were in the "oil window" between 420-330 million years ago, and oil from other formations that could be 300 million years old. Production from Lee County reached 60,000 barrels/day at one point, but wells tapped only small reservoirs in limestone cracks. One geologist noted:7

time-temperature model for generating oil/gas from organic material in source rocks underneath Lee County, Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Oil and Gas Well Data and Geology for Lee County, Virginia (Publication 113)

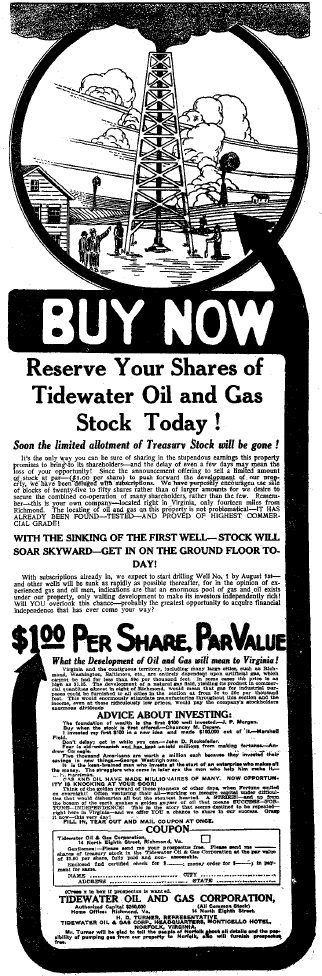

Some oil is produced from liquids that condense at natural gas wells in the Appalachian Plateau. Efforts to find commercial quantities of oil further east in the Triassic basins of the Piedmont have failed - so far. In the Richmond Basin, 38 exploratory holes were drilled between 1897 and 1985. In the Taylorsville Basin, six wells drilled since 1986 also failed to find enough hydrocarbons to justify further development.8

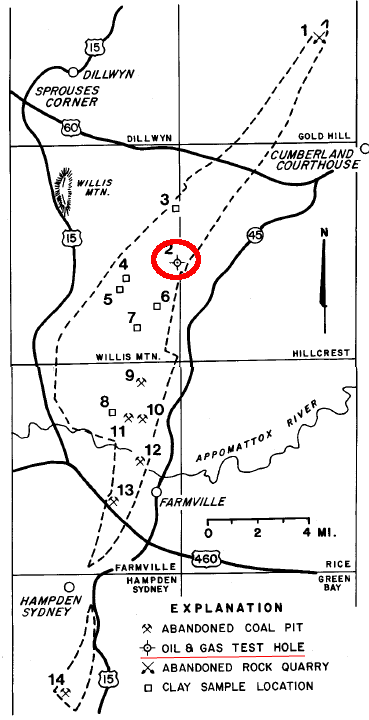

July 11, 1916 advertisement in Virginian-Pilot and Norfolk Landmark, to recruit investors for oil well in Prince Edward County

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Geology And Mineral Resources Of The Farmville Triassic Basin, Virginia

There are several potential oil and gas "plays" for future production in Virginia, especially after fracking technology has expanded the supply of natural gas from shale formations west of the Blue Ridge (such the Marcellus Shale). Due to the heat and pressure of thrust faulting and deep burial of sediments in western Virginia, the potential of finding liquid hydrocarbons that accumulated in the oil window (as opposed to natural gas) is limited.

New commercial-scale hydrocarbon discoveries in Virginia, if any, may generate natural gas or natural gas liquids rather than oil. Even offshore on the Outer Continental Shelf, the potential for gas is higher than for oil. The General Assembly passed legislation in 2020 that banned state agencies from authorizing any use of state-owned submerged lands within three miles of the coastline for either oil and gas development.9

The fear of "peak oil" limiting supply in 2010 had shifted a decade later to speculation that "peak demand" was on the horizon. As governments commit to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, the transportation sector will shift from gasoline-based vehicles to electric vehicles. In 2020, peak demand was anticipated to occur in the mid-2030's. The peak was expected to be followed by a gradual decline, as gas-based vehicles are slowly replaced and manufacturing adapts to other fuel sources.

The peak, somewhere between 199-115 million barrels/day with 13 million coming from the United States, may drop to 60-80 million barrels/day in 2050. Drilling for natural gas resources in the Taylorsville Basin, where commercial quantities of shale gas have not been identified, will become less economically attractive in that scenario.

location of Tidewater oil well, drilled in 1917 to 1,518 feet

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Geology And Mineral Resources Of The Farmville Triassic Basin, Virginia

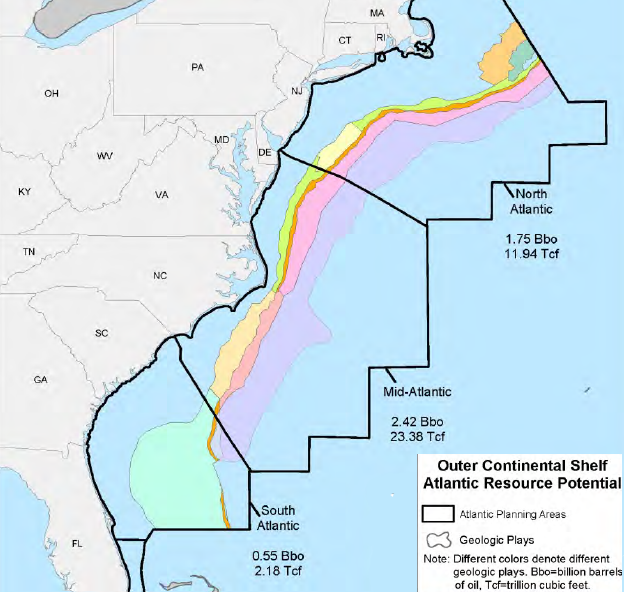

oil and gas resource estimates for the Outer Continental Shelf are defined primarily by reservoir-rock stratigraphy, and will remain speculative until test wells are drilled

Source: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, 2017-2022 OCS Oil and Gas Leasing Program - Proposed Program Decision Document, Geologic Plays in the Atlantic Planning Areas (Figure 5-5)

practicing placement of boom to capture oil spill in Elizabeth River

Source: U.S. National Response Team, Hampton Roads Geographic Response Plan - Development & PREP Exercise

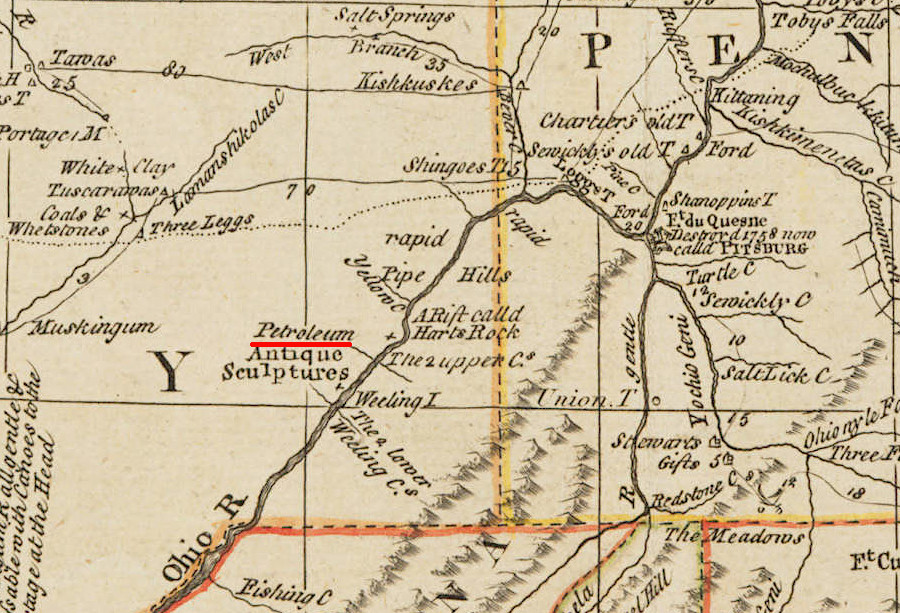

oil was found in Virginia (now West Virginia) in the 1700's

Source: Huntington Library, Bowles's new one-sheet map of the Independent States of Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, Pensylvania, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island &c (by Evan Lewis, 1796-1800)

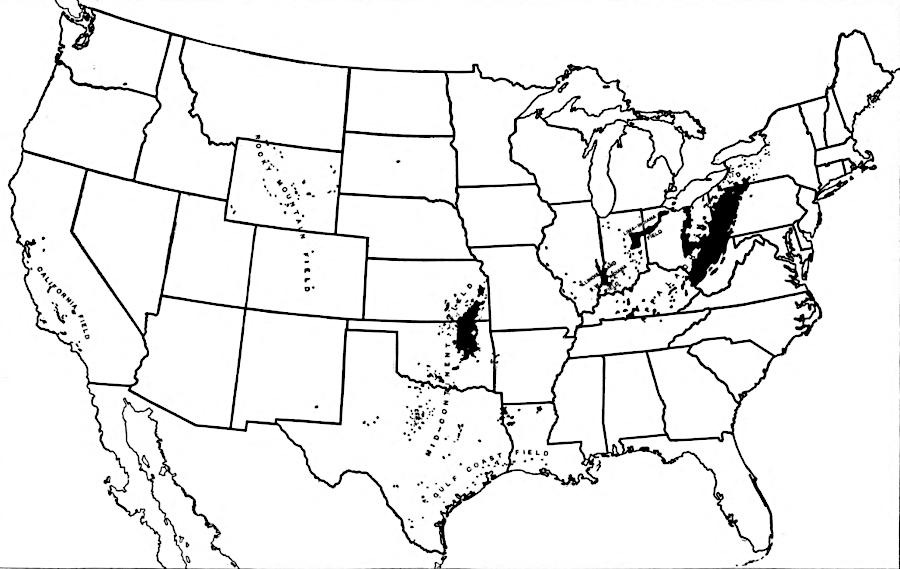

principal petroleum and natural gas fields in 1919

Source: Census Bureau, Statistical Atlas of the United States, 1920 (Mines and Quarries, Plate 356)