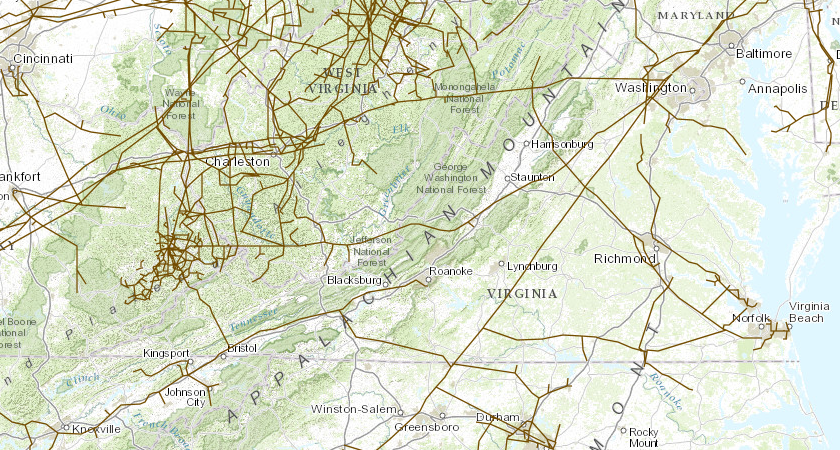

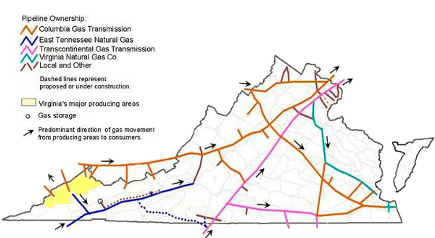

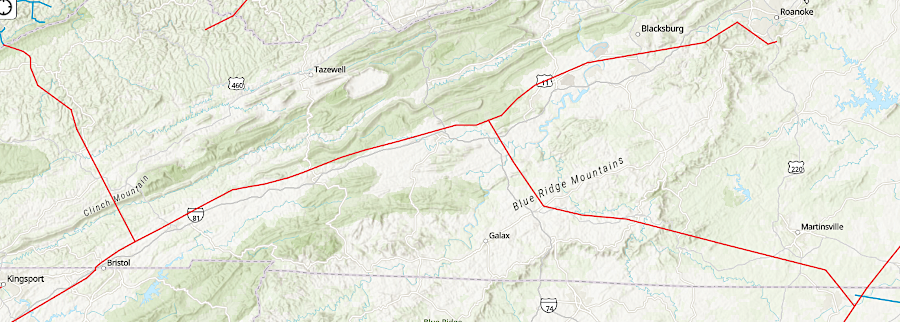

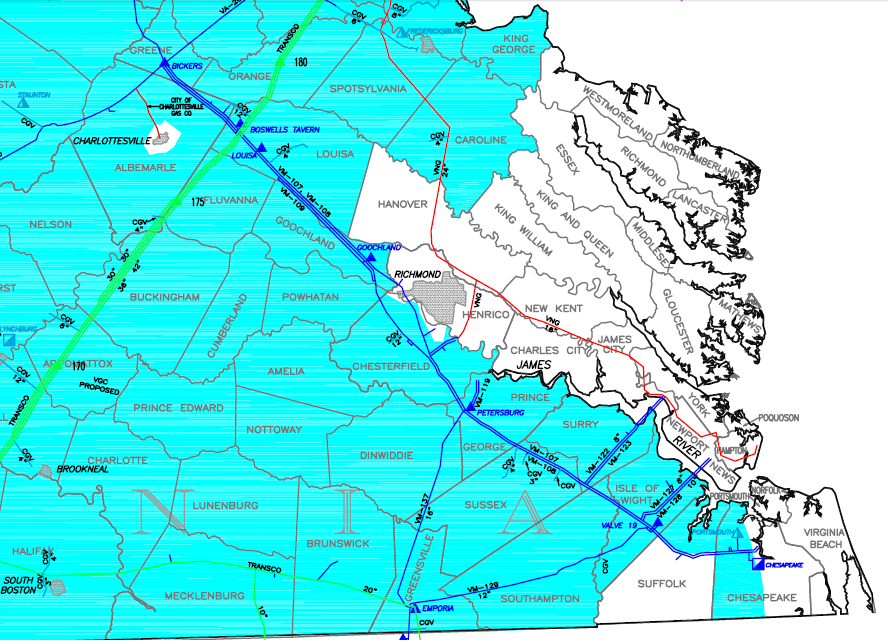

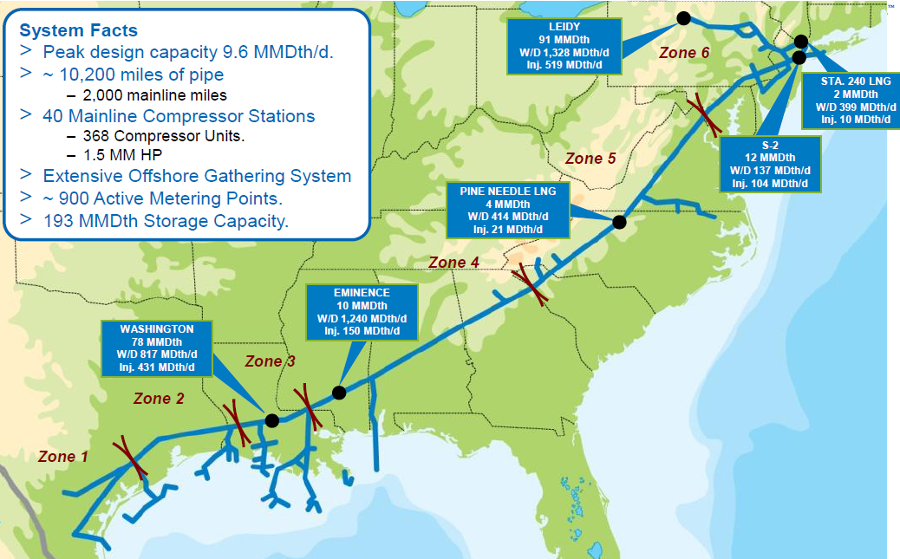

natural gas pipelines bring natural gas from the Gulf Coast and West Virginia/Ohio/Pennsylvania into Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

natural gas pipelines bring natural gas from the Gulf Coast and West Virginia/Ohio/Pennsylvania into Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Virginia imports over 50% of its natural gas via pipeline from out-of-state sources. A significant amount of natural gas is produced in southwestern Virginia, primarily methane from coal beds in the Appalachian Plateau. A tiny amount of methane is captured at landfills and even at wastewater treatment plants. In production, transport, and storage, some natural gas escapes and increases greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

In Virginia, two commercial oil fields produce natural gas as well as fluids. When natural gas is brought to the surface and the pressure is lowered, some hydrocarbon molecules condense from their gaseous state into liquid. Oil fields produce some gas, and gas fields produce some oil.

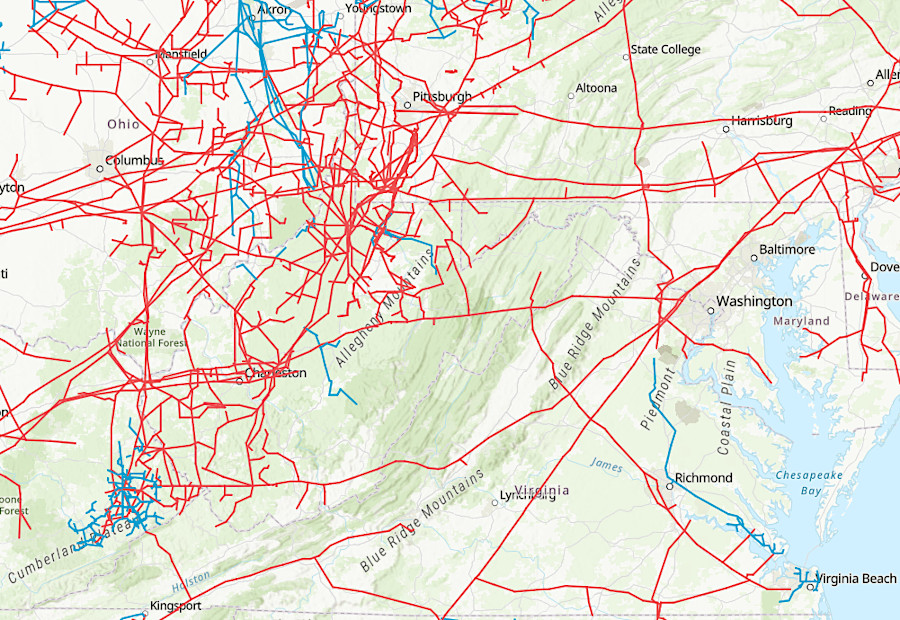

The condensates (natural gas liquids) extracted from the Marcellus Shale gas in West Virginia/Ohio provide raw material for refineries around Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. The natural gas produced from the Appalachian fields provides energy for refinery operations, but much is now shipped by pipeline to customers on the East Coast. Distribution by pipeline in the area has a long history. The first hydrocarbon pipelines in the United States were developed in western Pennsylvania, after Colonel Edwin Drake drilled the first oil well at Titusville in 1859.

Natural gas is treated before being distributed in a pipeline. Gas wells produce unwanted gases such as water vapor and hydrogen sulfide, in addition to valuable hydrocarbons. The water and hydrogen sulfide must be stripped out near the well before natural gas can be shipped in a pipeline, to avoid rust and other damage to the pipes and valves.

Coal bed methane includes roughly 10% carbon dioxide, but lacks much of the water vapor and other contaminating components found in "conventional" natural gas wells. Virginia's coal bed methane wells also lack the valuable liquid condensates, but require less processing before the gas can be transported via pipeline.1

Until World War Two, most natural gas extracted with oil at wells in Texas/Louisiana was burned as a waste product, "flared off" at the wellhead. There were no pipelines to transport natural gas to customers. Urban areas on the East Coast, including cities in Virginia such as Danville and Richmond, generated methane locally in "gas works."

Heating coal in a retort without oxygen produced methane, which was then stored in a "gasometer" and piped to local customers for industrial operations and residential lighting/heating. The residue, after driving off the methane, was coke.

Roanoke's first gasometer, built in 1883, was 60 feet in diameter and 16 feet in height and could store 50,000 cubic feet of gas. By 1908, there were three gas holders storing 375,000 cubic feet and by 1924 the Roanoke Gas Light Company could store 1,500,000 cubic feet. Customers connected to the local pipeline distribution network, including the Hotel Roanoke, could replace kerosene lights with gas. Lights with large glass globes illuminated Roanoke's streets from 6:00pm-11:00pm.2

During World War Two, the Federal government built two pipelines to bring oil from Texas to factories manufacturing industrial products in the Ohio River Valley, Philadelphia region, and ultimately New York/New Jersey. Pipeline transport was more expensive than shipping oil in tankers, but an inland route was needed to avoid the threat of German U-boats along the Atlantic Ocean coast.

German U-boats stimulated development of pipeline technology, leading to transport of natural gas under high pressure through Virginia

Source: National Park Service, Torpedo Junction

The 24-inch wide "Big Inch" pipeline carried crude oil to Illinois, Pennsylvania, and then to New York; the 20-inch wide "Little Inch" pipeline carried refined oil products (kerosene, diesel, etc.) on a parallel path. The successful construction of Big Inch and Little Inch demonstrated that modern steel and welding techniques could handle high pressure in large-diameter pipelines.

the Big Inch and Little Inch pipelines bypassed Virginia

Source: Texas Eastern Transmission Corporation, The Big Inch and Little Big Inch Pipelines

After the war, the oil companies returned to shipping their products from the Gulf Coast by tankers, and the Federal government auctioned off the Federally-owned Big Inch and Little Inch pipelines. Oil companies supported conversion of those two pipelines to transport natural gas rather than oil. Converting the pipelines to transport gas would reduce the risk that a new competitor could acquire and sell oil independently from the existing major oil companies.

Coal companies and railroads objected to Federal plans to convert the oil pipelines to move natural gas. Natural gas from the Gulf Coast, delivered through the two pipelines, could reduce the railroad's shipment of coal to the New York area. Some of that coal was used to manufacture methane, and the coal gas business would be reduced/eliminated once the pipelines provided an alternative source of natural gas.

A short strike of unionized coal workers in 1946 made clear the advantages of having an alternative energy source in the Northeast. Sale and conversion of the two oil pipelines in 1947 initiated large-scale use of Gulf Coast natural gas in the Northeastern states.

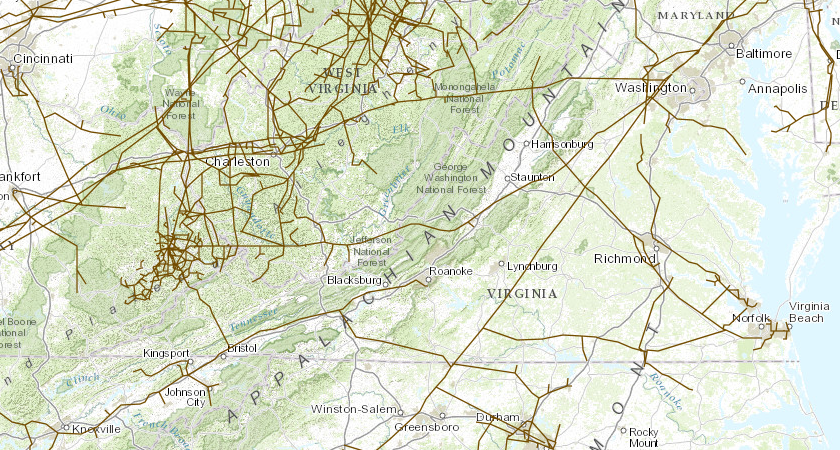

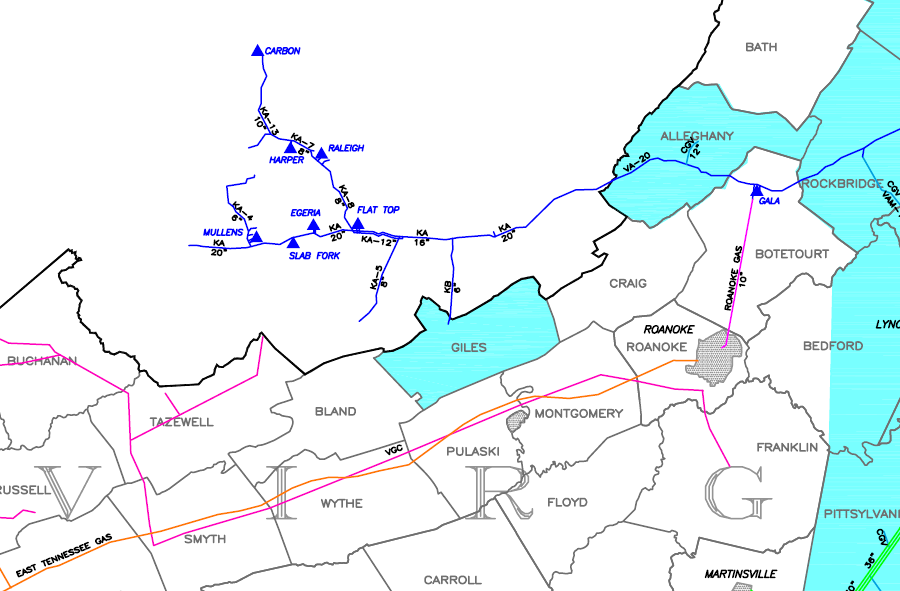

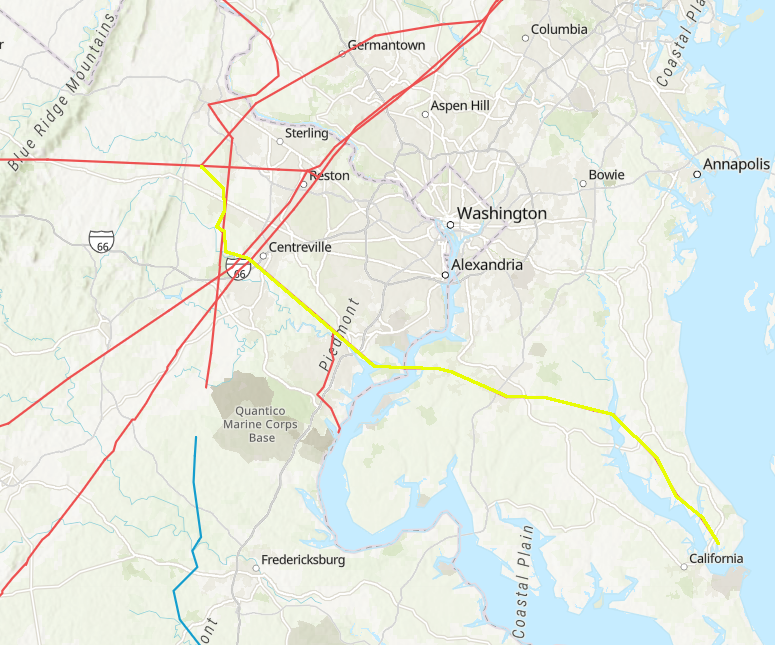

pipelines owned by Transco, Columbia, and East Tennessee are the primary transporters of natural gas into Virginia

Source: Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Piedmont Gas Supply Sources

After Texas Eastern purchased the Big Inch and Little Inch pipelines, a competitor emerged. Transcontinental Gas Pipe Line (Transco) built a new distribution system on the eastern side of the Appalachian Mountains to carry Gulf Coast gas north to service cities on the Piedmont (such as Atlanta and Charlotte) and ultimately the New York market. Thanks to pipelines built on both sides of the Appalachians, natural gas from the Gulf Coast finally could replace higher-cost coal gas.

Texas Eastern was required to sell gas to existing customers along its route through Illinois to New York, limiting the volume it could deliver to New York City utilities. As a new pipeline along the eastern side of the mountains, Transco had an advantage - it had no existing customers. Transco signed contracts with some customers in Virginia such as Danville, but reserved enough volume so Transco could become the dominant supplier in New York and earn higher profits.3

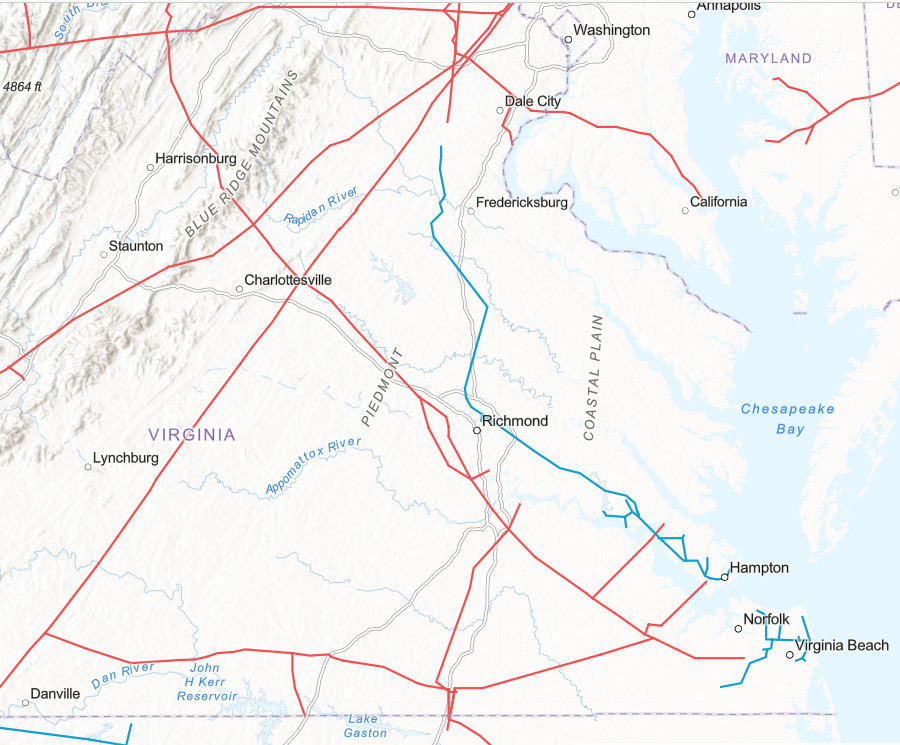

The Transco pipeline today is owned by Williams Companies. It is still the primary trunk pipeline that carries natural gas from the Gulf of Mexico and adjacent states to Virginia, but the direction of flow is being reversed.

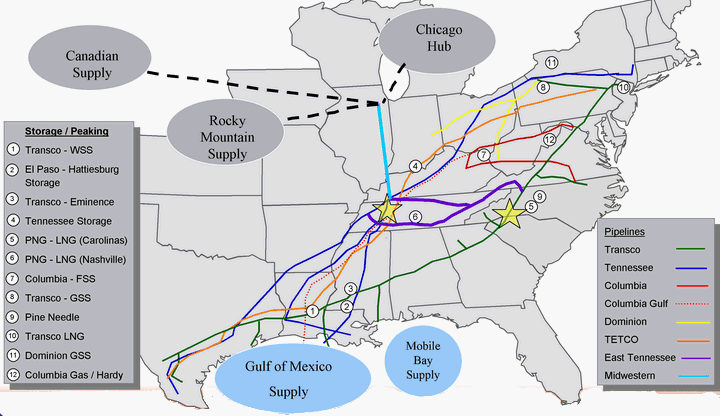

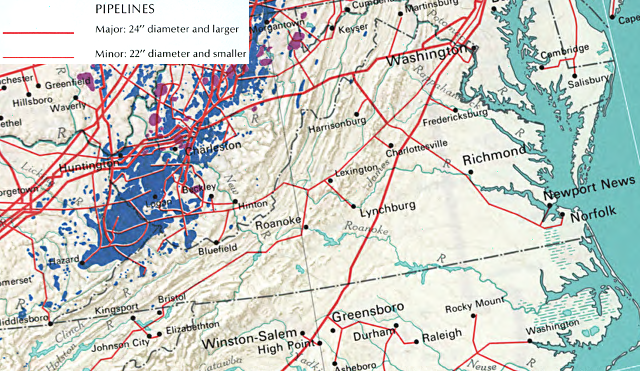

much of Southside Virginia had no large pipeline providing natural gas in 1970, limiting the region's ability to recruit new manufacturing facilities

Source: Library of Congress, "The national atlas of the United States of America," Natural Gas Pipelines

After development of the Ohio, Marcellus, and Utica shale gas fields through fracking, that pipeline can now bring gas from West Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania south to Virginia. The company will expand pipeline capacity across Pennsylvania (the Atlantic Sunrise Project) and push gas in the main pipeline towards the south. The company's proposed Appalachian Connector project would provide a new link bringing Appalachian gas to the existing Transco pipeline in Virginia, joining at the Transco Station 165 compressor station in Pittsylvania County.

Two other companies, Enbridge (which acquired Spectra in 2017) and Columbia Gas (now part of NiSource), own the other two major interstate pipelines bringing natural gas into Virginia. Both of those trunk lines bring Gulf Coast and Appalachian gas eastward into Virginia. In 1950, the Roanoke Gas Company built a 30-mile pipeline to Gala in Botetourt County to obtain gas from the 10-inch Columbia pipeline that had been constructed in 1931. That source allowed the company to shut down its gas works in Roanoke.4

in 1950, Roanoke Gas Company built its connection to the Columbia Gas pipeline at Gala in Botetourt County

Source: Columbia Gas, Certificated Natural Gas Service Areas

Texas Eastern still uses the former Big Inch and Little Inch pipelines to deliver natural gas to New York City and New England. An extension from those historic pipelines, the East Tennessee Natural Gas pipeline, serves southwestern Virginia. The East Tennessee Natural Gas pipeline also transports coal bed methane generated in the coal fields of southwestern Virginia. Both Texas Eastern and East Tennessee Natural Gas are subsidiaries of Spectra Energy now.

the first Transco natural gas pipeline connected the Gulf Coast with the Northeast, but now can bring gas from Pennsylvania/Ohio south to Virginia

Source: Williams Company, Gas Pipeline Asset Map

In addition to Transco (Williams) and the East Tennessee Natural Gas pipeline (Spectra Energy), Virginia receives large supplies of natural gas from two other interstate pipeline companies. Columbia Gas Transmission has two major pipelines that cross into Virginia from its western border to supply both Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads.

Transco, Spectra and Columbia Gas own the major interstate trunk pipelines bringing natural gas to Virginia

Source: 2010 Virginia Energy Plan, Section 5 - Natural Gas

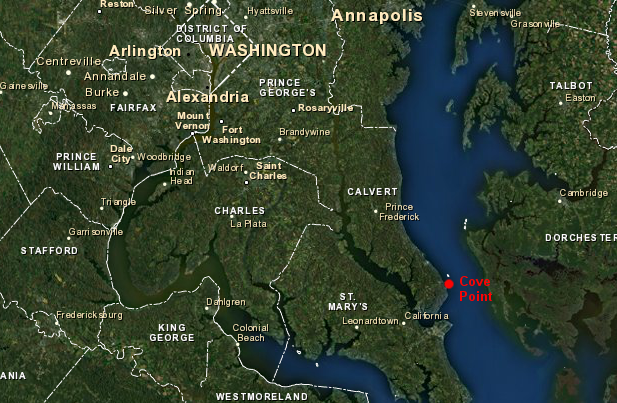

Dominion Transmission, a subsidiary of the same company that dominates the electricity market in Virginia, built a pipeline to carry natural gas from Maryland to the Possum Point electricity generating plant in Prince William County. That pipeline was planned to carry gas from the Cove Point Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) terminal in Maryland to Possum Point.

After the success of fracking in the Appalachian Basin, Dominion decided to reconfigure the Cove Point terminal to export, rather than import, Liquefied Natural Gas. The first shipment left the terminal in March, 2018. It was supposed to go to Asia via the Panama Canal, but was diverted to the United Kingdom. A cold snap created a spike in demand with a customer willing to pay a higher price, so that LNG tanker became the first to change destinations mid-route.

The primary supply for Possum Point became gas from Appalachian shale basins, delivered via pipeline from Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia. In 2018, Dominion planned to add a third compressor station to the pipeline to increase its capacity.

The initial site planned for the compressor station was in Charles County, Maryland, across the Potomac River from Mount Vernon. The historical view from George Washington's home would be affected if the two exhaust stacks were visible. Piscataway Park had been created to protect that view in the 1960's, when sewage treatment plants and oil storage facilities were proposed near the Maryland shoreline.

Though Dominion claimed the stacks would be screened by trees, the company later agreed to find another location.5

the East Tennessee Natural Gas pipeline carries gas into southwestern Virginia via Tennessee and West Virginia

Source: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), EnviroMapper

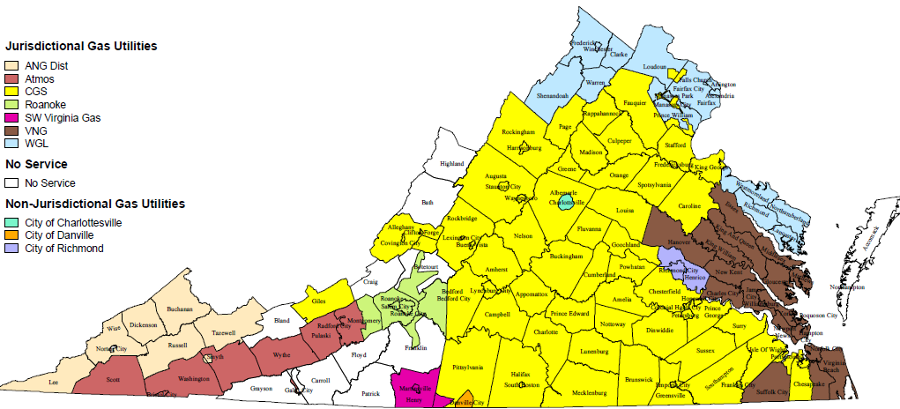

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) regulates interstate pipelines. The State Corporation Commission regulates pipelines that are located only within the Virginia. Within the state, Virginia Natural Gas owns the largest intrastate gas pipeline, carrying gas from the Transco system in Northern Virginia to Richmond and Hampton Roads.

transmission companies deliver natural gas to Local Distribution Companies, which have their own network of intrastate pipelines to distribute the gas to end users (investor-owned LDC's are utilities regulated by the SCC, while municipal LDC's are outside of SCC jurisdiction)

Source: State Corporation Commission, Map of Service Territories

Natural gas is pumped through underground pipelines with compressor stations every 40-100 miles to maintain pressure. Trunk lines may be under as much as 1,000 pounds/square inch pressure, while distribution line pressure is 60-150 pounds/square inch. The pressurized gas is transported in the form of a gas.

In theory, more volume could be transported within a pipeline if the gas was cooled to -260°F and converted into a liquid, but the cost to insulate the pipe and install chillers/compressors would not be economical. However, heavy hydrocarbon gases such as propane (C3H8), pentane (C5H12) and butane (C4H10), which have the highest British thermal unit (BTU) value, do not require the intense refrigeration necessary to liquefy gases such as methane (CH4). Those gases can be liquified at -50°F and sold separately as Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG). Many backyard grills are fueled by small cylinders of propane sold at hardware stores and 7-11's.

Virginia has 3,000 miles of high-pressure natural gas "trunk" pipelines, plus 20,000 miles of lower-pressure, smaller-diameter distribution pipes connecting to 1.2 million customers, plus about 10 miles of regulated "gathering lines" that connect gas-production wells to the pipeline network. The State Corporation Commission oversees safety for the intrastate distribution lines, including those from propane tanks if the lines serve at least 10 end customers or cross property lines and/or public space (such as a right-of-way).6

Liquefied Natural Gas tankers in the Chesapeake Bay require additional security from the Coast Guard

Source: US Coast Guard

The price of conventional natural gas and coal bed methane produced in Virginia, and the cost of natural gas used by Virginia customers, is shaped by an international energy market. Supply and demand are affected by international events, with intermittent crises triggering spikes in prices.

International agreements based on policy, such as the volume and prices of gas sales from Russia to European countries, warp the way prices could have been established through the standard laws of supply and demand. Increases in supply require more time to affect prices than interruptions that political/military/terrorist actions that block deliveries, since massive investments in infrastructure are required to move additional natural gas through Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) tankers or through pipelines.

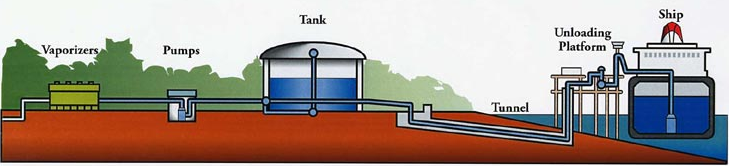

Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) is cooled to -260 degrees Fahrenheit and kept liquid in well-insulated cryogenic tanks,

so gas is vaporized before it transported at normal temperature for long distances by pipeline

Source: Dominion Energy, Dominion Cove Point LNG

Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG), cooled to -260°F to compress the gas into liquid form, can be imported into Virginia via the Cove Point LNG facility in Maryland, or exported through that same location. The Cove Point facility was built after the 1973 energy crisis, when the oil cartel increased prices after the Yom Kippur war in the Middle East. Existing pipelines could not ship a sufficient supply of natural gas from Texas to the Northeast. After a great deal of debate, the Liquefied Natural Gas terminal was constructed in Maryland to import natural gas from Algeria.

Following completion, the economics of the energy business changed again. After passage of the Natural Gas Policy Act of 1978, prices for natural gas were deregulated in the US. Energy companies developed more of the resource, especially shale gas reservoirs starting with the Barnett Shale in Texas during the 1980's.

The shale reservoirs had been classified as unconventional sources of natural gas, because the low porosity of the shale formations blocked gas molecules from migrating to a wellbore. Fracturing the shale with water under pressure, then propping open the fractures with sand particles injected in the hydraulic fracturing process, created artificial pathways through the rock formations and made it economical to recover the gas. After production from shale reservoirs became common, the US Geological Survey changed its terminology and now describes shale formations as "continuous" rather than as "unconventional" reservoirs.7

After the cost of US natural gas dropped below the cost of imported Liquefied Natural Gas, the Cove Point terminal was idled between 1988-2003 until rising demand exceeded domestic supply again. At the start of the 21st Century, demand for natural gas outstripped supply again, and new focus was placed on Liquefied Natural Gas ports.

Dominion Energy purchased the facility in 2002, and after 2003 Cove Point imported Liquefied Natural Gas from Trinidad, Nigeria, Norway, Venezuela and Algeria.8

The development of shale gas through horizontal drilling and "fracking" shifted the industry's economics again. Drilling in the Marcellus and Utica shales in the Appalachian basin, and other strata elsewhere in the United States, dramatically increased supply of natural gas.

While all that gas could be used within the United States, foreign customers are willing to pay more for the gas than domestic customers - especially when political disputes in Europe affect the willingness and ability of Russia to export its gas to Germany, Poland, and Ukraine.

Cove Point was retrofitted to serve as an export terminal. It liquified natural gas obtained from the Transcontinental Gas Pipeline, Columbia Gas Transmission pipeline, and Dominion Energy Transmission pipeline, then shipped it to foreign customers. Dominion Energy sold its natural gas assets after cancelling the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, and Berkshire Hathaway Energy acquired control of Cove Point. In 2020, Cove Point exported 4.85 million tons of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG).

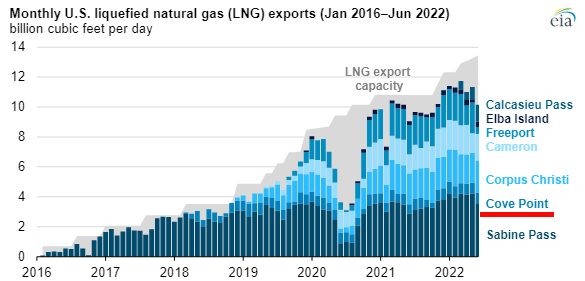

by 2022, exports from Cove Point were exceeded by other Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) terminals

Source: Energy Information Administration, The United States became the world's largest LNG exporter in the first half of 2022

The 2022 war in Ukraine dramatically increased demand for LNG. European countries that had expected to increase supply from Russia decided instead to cancel the Nord Stream 2 pipeline project and purchase LNG as the alternative.

In the United States, seven LNG export terminals were in operation in 2022. Four new terminals under construction in Texas and Louisiana would increase export capacity by 80%, adding 83 million metric tons per year of export capacity. There were also six proposed new LNG export terminals and three expansion projects, which would add 97 million metric tons of LNG capacity.

A barrel of oil has roughly six times the energy of 1,000 cubic feet of natural gas, so when the price of oil is more than six times the price of gas (a 6:1 ratio), customers seek to shift to gas. With the new supply of shale gas, the price of gas in the domestic US market has dropped far below the 6:1 ratio.

When oil was close to $100/barrel and gas was less than $4.00 per thousand cubic feet, the ratio was 25:1. Not surprisingly, the Federal government received proposals to export 30 billion cubic feet/day, as much as 1/3 of domestically-produced gas, to foreign customers.9

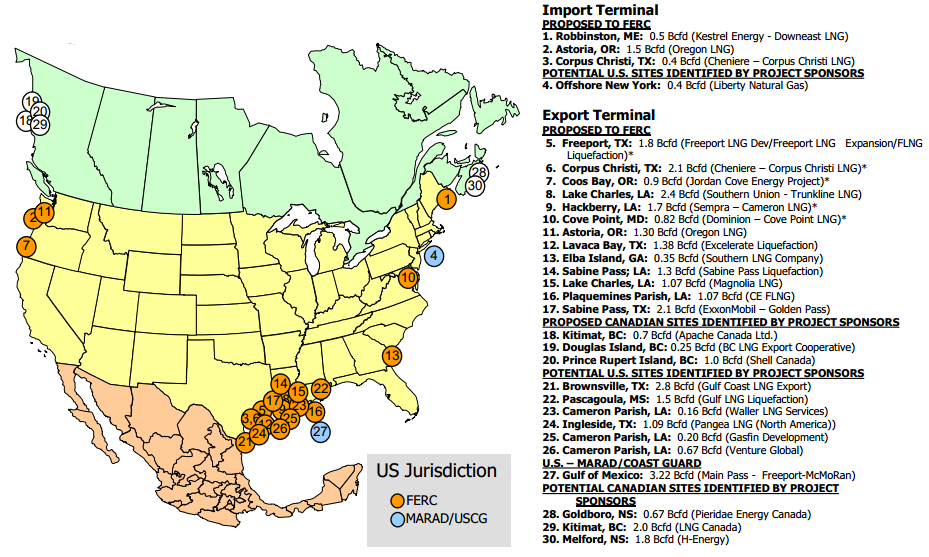

Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) terminals located in the Gulf of Mexico or Georgia are further from gas produced in the Appalachian shale basin than Cove Point, giving it a competitive advantage

Source: Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), North American LNG Import/Export Terminals - Proposed/Potential

Long-operational pipelines to Mexico and Canada can not reduce the domestic surplus sufficiently. In particular, gas from the North Slope of Alaska could be exported overseas, rather than shipped by pipeline or tanker to markets in the Lower 48.

An Energy Information Administration study calculated that authorizing Liquefied Natural Gas exports could increase the price of natural gas in the United States by 3-9%, but gas prices still were predicted to be low enough to spur a dramatic increase in the chemical industry as plants were built to use gas as a raw material for manufacturing plastics and other products. The cost differential between US-produced gas and foreign gas/oil makes Liquefied Natural Gas transport to Korea, Japan, China, India, Great Britain, and other customers via tankers very attractive. In 2013, the key statistics were:10

Based on those numbers, Virginia's chemical plants concentrated in Hopewell should anticipate prices for feedstock will be determined by demand in Asia as much as by increased shale gas supplies. Though permit applications were received to export 1/3 of domestic supply, Algeria, Russia, and other producers will meet much of that demand.

The US Department of Energy authorized Dominion to use Cove Point to export gas in 2011. Dominion later requested expansion of that authority to export Liquefied Natural Gas to countries not part of a free trade agreement - including Japan and India, with which Dominion already had signed contracts for 100% of the export capacity. Dominion insulated itself against potential changes in gas prices and guaranteed itself a profit by contracting only to provide terminal services at Cove Point; customers will purchases the natural gas in separate contracts, and Dominion will get paid not matter how energy prices fluctuate. As a Dominion official noted:11

In 2013, Dominion formally obtained Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approval to modify Cove Point so the utility could export US-produced Liquefied Natural Gas, as well as import Liquefied Natural Gas if the market shifted again in the future.

seven tanks at Cove Point store Liquified Natural Gas - for export, now

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Cove Point was not the only Liquefied Natural Gas terminal on the East Coast that was repurposed for export. The Elba Island terminal near Savannah, Georgia was also approved for conversion from an import into a Liquefied Natural Gas export facility.

Because of its location, Cove Point had a competitive advantage for exporting gas produced in the Marcellus shale, while the Savannah facility has a shorter pipeline path for Gulf Coast gas. Other Liquefied Natural Gas export terminals in Texas are even closer to Gulf Coast gas than Elba Island in Georgia. The US Department of Energy did not approve/reject facilities based on the economics of gas transport; it allowed the market to determine which facilities would ultimately become successful.12

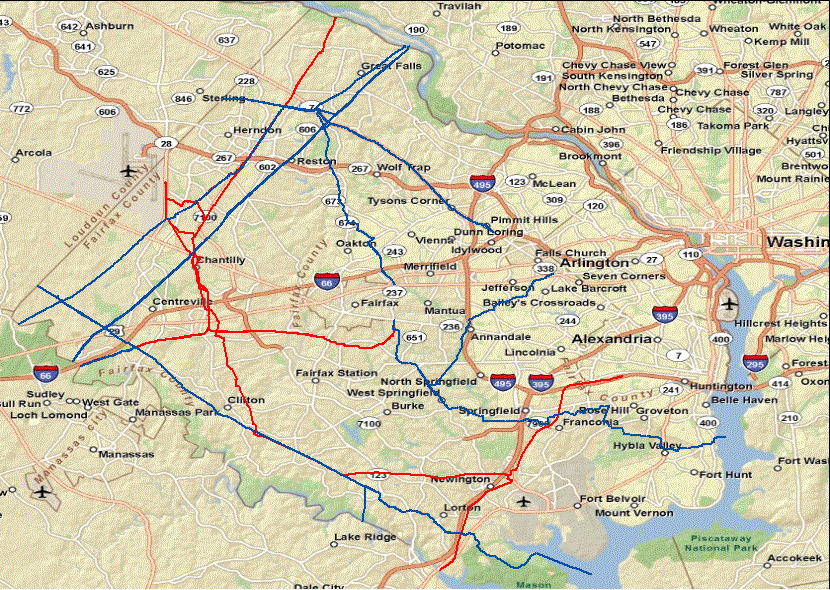

Exporting Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) from Cove Point required upgrading compressor stations in Loudoun/Fairfax counties to increase pipeline capacity.13

the gas transmission system in northern Virginia, such as Dominion's Measuring and Regulating site in Loudoun County, will be enhanced to push more gas to Cove Point

Source: Dominion Energy, Cove Point Liquefaction Project Update (June 2013)

The gas pipeline system consists of expensive, fixed infrastructure, but the movement of gas can still be revised to reflect changes in supply (as at Cove Point, or in newly-developed shale gas basins) or in changes in demand. In 2003, Dominion converted Units 3 & 4 at the Possum Point power plant in Prince William County from coal to natural gas, and added a 550-megawatt combined-cycle Unit 6 (with two conventional combustion turbines and a steam turbine) that can burn either natural gas or #2 fuel oil. The conversion helped meet air pollution mandates required to settle a lawsuit between EPA and Dominion in 2000 regarding emissions from Mount Storm, as well as take advantage of the relatively low price of gas.14

That altered demand for gas in the area. The units, generating 336 megawatts, were supplied with natural gas through a 14-mile pipeline extension that provided access to Liquefied Natural Gas imported at Cove Point. However, domestic sources rather than Algeria, Nigeria, etc. ended up providing the natural gas for Possum Point.15

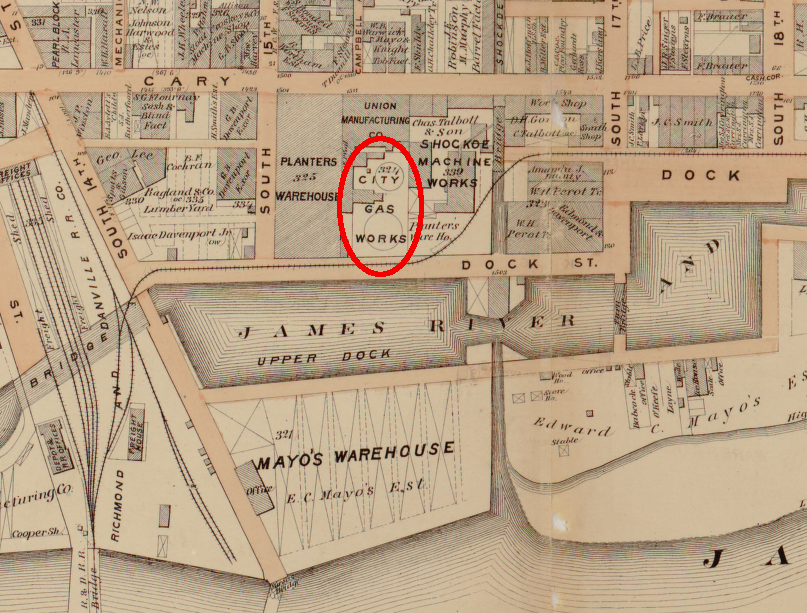

Before natural gas pipelines brought gas from the Gulf Coast and Appalachian gas fields, local municipalities and some industries in Virginia manufactured methane from coal. Coal was heated in a tank from which oxygen was excluded, causing the release of methane or "coal gas." The second demonstration in the United States of how methane could be generated from coal was in Richmond, in 1802. Starting in the 1850's, the Fulton Gas Works operated for nearly 100 years.16

Arlington, Danville, Fredericksburg, Lynchburg, Norfolk, Newport News, Portsmouth, Richmond, Roanoke, and Suffolk produced methane from coal gasification plants ("gasworks"), for local use. They distributed methane generated at local gasworks through a network of local underground pipes to nearby customers.

When the Transco pipeline was constructed through Virginia in 1950, the Water and Gas Distribution Department of Danville and equivalent municipal utilities in other cities in Virginia switched from manufacturing methane from coal to using pipeline-supplied natural gas. The increased supply allowed utilities to expand their network of local pipes. Though the number of houses/businesses able to get gas has increased, the cost of constructing and maintaining those pipes still causes utilities to limit the geographic areas served by gas.17

Natural gas is a high-volume, low-energy product, so storage requires compression to a smaller volume for storage in a tank or use of a large underground space that can contain the gas. To ensure adequate supplies during the winter, Spectra Energy transports natural gas during the summer via the East Tennessee Natural Gas pipeline to the depleted gas field at Early Grove and Saltville, where it stores the gas underground for withdrawal during periods of high demand.

natural gas lines (blue) in Scott County connect the Early Grove storage reservoir to the East Tennessee Natural Gas pipeline

Source: US Department of Transportation, National Pipeline Mapping System, Public Viewer

Spectra injects gas underground when demand is low, then extracts gas when demand increases during the winter. The underground storage uses caverns that were excavated when Olin Corporation pumped salt brine to the surface for its chlorine and caustic soda business, plus additional caverns created by solution mining since 1994 just to store natural gas.18

Cove Point Liquefied Natural Gas facility, on the Chesapeake Bay where ocean-going tankers can dock

Map Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

the Cove Point pipeline (yellow)

Source: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), EnviroMapper

in Richmond, the gas works were located in Shockoe Creek valley, where coal could be provided by canal or railroad

Source: Library of Congress, Illustrated atlas of the city of Richmond, Va. (Section L, 1877)

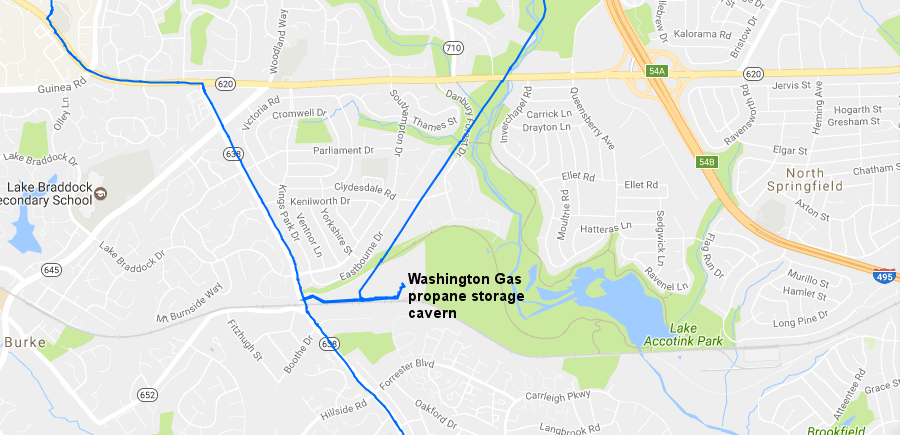

Natural gas is not shipped just by pipeline. Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) or LP gas (compressed propane, with various percentages of butane, propylene, and butylene) has higher energy than methane and is shipped in rail cars to terminals near railroad lines. Tanker cars also deliver propane the Washington Gas storage cavern at Ravensworth in Fairfax County. The propane is used for "peak shaving" when demand is highest. It is withdrawn from the cavern, mixed with air to form natural gas, and then distributed by pipeline to customers.

propane is delivered to the Ravensworth facility of Washington Gas by railroad in tanker cars, stored underground, and mixed with air before being distributed to customers via pipeline (blue lines)

Source: US Department of Transportation, National Pipeline Mapping System, Public Viewer

Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) also has been trucked to the city of Roanoke from North Carolina and stored in terminals there for years. In 2013 a company proposed building a new terminal that would be supplied by two rail deliveries daily during the heating season. The area was zoned for industrial use, but neighbors in the Morningside community quickly expressed concern about constructing three 60,000-gallon propane tanks and two 90,000-gallon butane tanks within a quarter-mile of housing. One reason for their concern was that propane is heavier than air. A leak in a propane storage tank or pipeline could result in a pool of gas collecting in a low spot, until a spark ignited an explosion.19

Propane is transported by truck from terminals to propane storage terminals that serve customers located far from the railroads or pipelines. Individual trucks can carry 7,000-12,000 gallons of propane. Smaller "bobtail" trucks can deliver 1,000-5,000 gallons from terminals to individual houses and businesses. Even in isolated rural areas, customers can use natural gas for heating and cooking. Farmers get propane deliveries by truck, and use it to dry grain to the preferred moisture level before storage in a silo.20

propane delivery truck on Route 15 near Leesburg

Some homeowners get one or more visits each winter from a large truck to refill the propane tank that supplies the furnace and kitchen. People who use an outdoor grill purchase cylinders filled with compressed propane at nearby stores, and transport the propane back home via personal vehicles. Trucks loaded with many cylinders of propane drive through neighborhoods regularly to restock the racks at retail outlets, and tankers travel suburban streets and rural roads to refill propane tanks at individual houses.

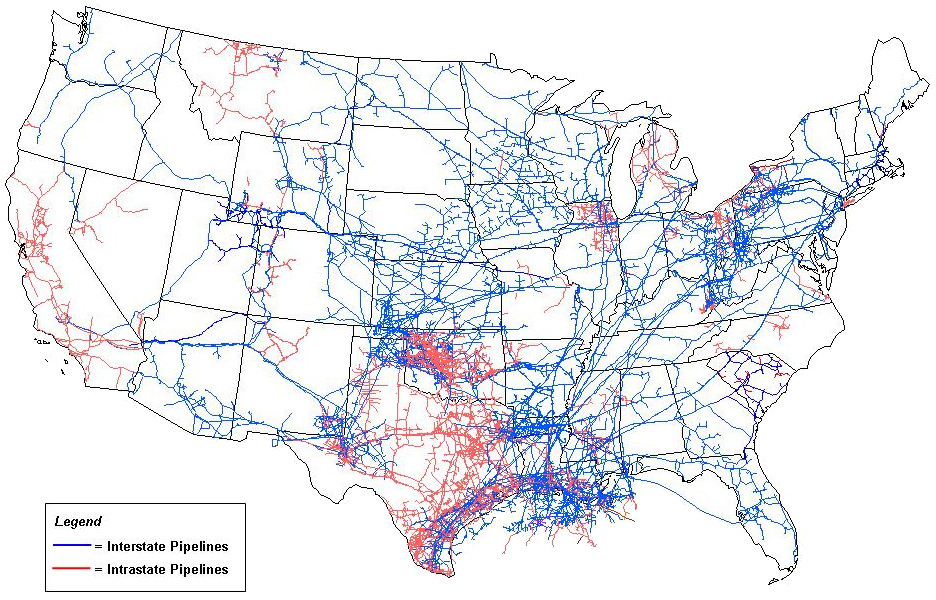

network of natural gas pipelines in the US

Source: US Energy Information Administration, U.S. Natural Gas Pipeline Network

Transport of gas into Virginia via pipeline is a separate business from retail sales of natural gas to individual customers. Homeowners pay their natural gas bills to utilities, not to the major pipeline companies.

Trunk lines such as Transco are "common carriers." They build large-diameter pipelines and transport large volumes of natural gas to utilities. Pressures in the steel pipelines can be 1,200-1,500 pounds per square inch (psi).

Utilities operate a network of small-diameter pipelines, and sell the gas directly to final customers. The older pipes may be constructed from wrought iron, and the youngest pipes may be plastic. Pressures in distribution systems are typically around 60 psi, though some high-pressure "mains" can carry gas at 150 psi.21

Until 1993, interstate pipelines purchased gas and then sold it to local distribution companies. The pipeline had a monopoly, except in rare cases where a local distribution company had a connection to a second pipeline. Deregulation of natural gas started after the energy crisis of 1973. The ability to sell natural gas at market prices, rather than government-regulated prices, stimulated new drilling and led to a major increase in the supply of natural gas.

In 1993, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) Order 636 unbundled pipeline services. Local distributers became responsible for buying natural gas from whatever supplier they chose, and then contracting with the pipeline just to transport the gas. Order 636 allowed local distribution companies to seek competitive bids in order to purchase natural gas at lower prices. Deregulation also shifted to local distributers all the risk of projecting the "heating degree days" in the winter and estimating demand. Pipelines make an extra profit if a utility orders an insufficient supply in a cold winter and needs a last-minute boost, or purchased transport services for more gas than was required in a warm winter.22

Demand for natural gas fluctuates according to the weather, so the distribution pipeline network is sized to meet the projected peak demand. Utilities contract in advance with pipelines for a specific minimum quantity of gas to ensure sufficient deliveries to met anticipated customer demand. Major users of natural gas, such as manufacturing facilities, may contract in advance with utilities for a guaranteed supply.

Homeowners take only the gas that they require, and demand mostly reflects the weather. In a warm winter, homeowners may use significantly less gas than utilities anticipated. In a cold winter, homeowners expect a steady supply of gas and rely upon the utility to deliver the volume needed to keep the house warm.

Utilities must adjust deliveries to match demand. In long spells of cold weather, gas furnaces to heat structures run constantly and utilities may not be able to deliver all the gas required. Contracts with large users may be based on an "interruptible tariff," allowing the utility to curtail delivery so the demand from homeowners can be satisfied. Industrial customers negotiate price discounts in exchange for their agreement to have as deliveries interrupted, which may require shifting to another fuel or even shutting down a facility temporarily.

The State Corporation Commission (SCC) defines the boundaries of exclusive service areas for gas distribution companies in Virginia. The rates for natural gas service are established by the SCC, and companies must obtain state approval before raising or lowering rates. Eliminating competition for gas distribution reduces the cost of building the pipeline infrastructure to service customers. In exchange for the monopoly, distribution companies must accept state regulation.

Importing natural gas via pipelines is an alternative to importing electricity via transmission lines regulated by PJM, the Regional Transmission Organization (RTO). In 2010, Virginia imported 41% of the 124 terawatt hours (TWh) of energy consumed within the state. Completion of new electricity generating power stations by 2020 allowed that percentage to drop to 18%.

Dominion Energy obtained permission from the State Corporation Commission in 2025 to build a 25-million gallon liquified natural gas storage facility that would serve its Brunswick and Greensville power stations. The utility wanted to store natural gas near those facilities because it did not trust the reliability of delivery through long-distance pipelines:23

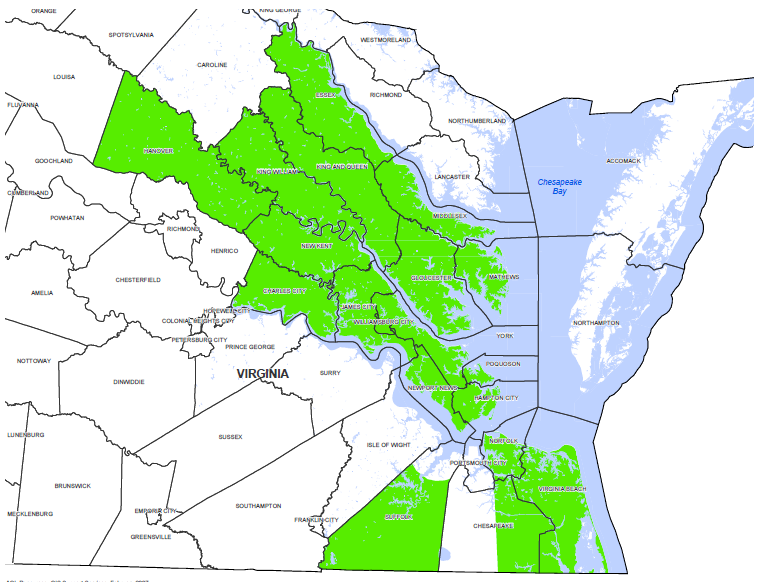

The exclusive service areas are easy to see when examining maps of service areas in Tidewater Virginia for Virginia Natural Gas (a subsidiary of Southern Company) and Columbia Gas of Virginia (a subsidiary of NiSource), especially in the cities of Suffolk, Chesapeake, and Virginia Beach in Hampton Roads:

Columbia Gas distribution service area

Source: Columbia Gas of Virginia

Virginia Natural Gas service area

Source: Virginia Natural Gas service area

Virginia Natural Gas pipeline (blue)

Source: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), EnviroMapper

Virginia Natural Gas operates a intrastate pipeline, within the borders of just Virginia, to distribute gas to customers on the Middle Peninsula, the Peninsula, and in Hampton Roads. In 2010, Virginia Natural Gas connected its separate networks of pipelines in Hampton Roads, located on opposite sides of the James River. The underwater Hampton Roads Crossing linked the south side of Hampton Roads, supplied from the Columbia Gas Transmission pipeline, with the Peninsula side (north of the river) supplied by Dominion Transmission.

The project used continuous underwater horizontal directional drilling to install pipe under the shipping channel in the Elizabeth River and between Craney Island-Hampton, and set a world record for the length of such drilling. The less expensive technique of trenching-and-filling, which creates more environmental impact on the clam/oyster beds due to suspended sediment, was used in places. Horizontal directional drilling was also used when Washington Gas installed a new distribution line under the Occoquan reservoir to supply customers in Prince William County.24

Construction of the Hampton Roads Crossing did not increase the amount of natural gas available in Hampton Roads, but did give Virginia Natural Gas greater flexibility for maintaining pressure in its system. The company sought to increase the total volume of available gas by joining the consortium that proposed the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, an interstate project. Importing gas from the Marcellus shale in Ohio/West Virginia would allow Virginia Natural Gas to supply major new industrial companies in Hampton Roads.

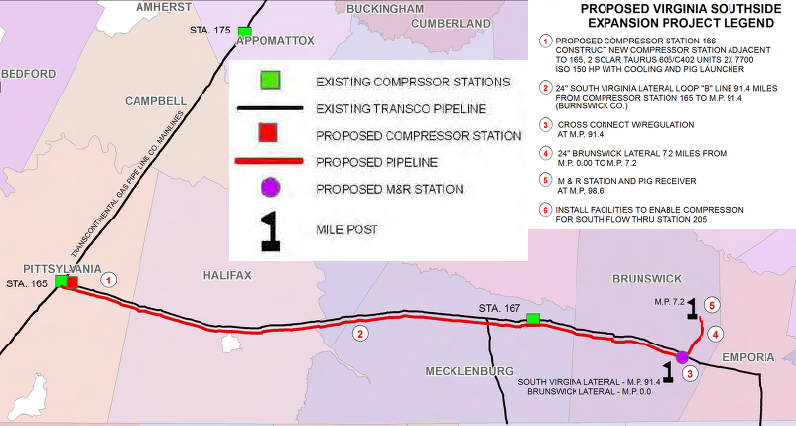

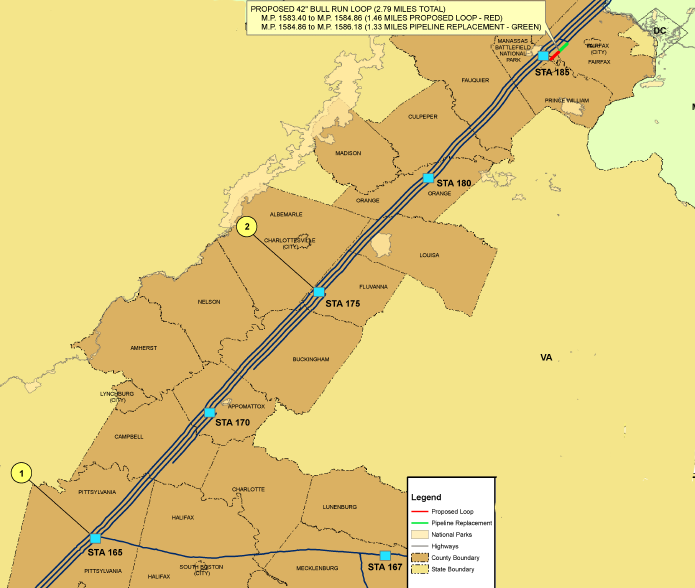

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) must issue a "Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity" to approve new transmission pipelines. For example, when Dominion decided to build a new 1,300 megawatt electricity generation power plant in Brunswick County and use natural gas as the fuel source (while shutting down two older coal-fired power plants), the existing pipeline to the region was already operating at full capacity. Both FERC and the SCC had to approve the Virginia Southside Expansion of the Transco pipeline and must approve proposed competitors, such as the Atlantic Coast Pipeline.

Virginia Southside Expansion, bringing natural gas from main Transco pipeline to new gas-fired power plant in Brunswick County

Source: Williams Company Virginia Southside Expansion

The safety of gas pipelines depends upon the maintenance of the infrastructure. Metal pipe corrodes in the ground, and the high-pressure gas can break through at welds or thinned sections of pipe. Transmission lines must be inspected by a variety of techniques (including "smart pigs" that move inside the pipes to test wall thickness).

In 2008, the Transco pipeline exploded dramatically near Appomattox. Williams, owner of the pipeline, was fined nearly $1 million by the US Department of Transportation for failure to monitor corrosion adequately. A hydrostatic test of the Virginia Southside Expansion revealed a leak before the pipeline was put into service. The leak created only "a small hole in the ground where the water escaped," revealing a weak pipe joint that was quickly replaced.25

Leaks can also be revealed by odor. Natural gas is naturally odorless. A chemical with a pungent odor, mercaptan, is added so gas will be easier to smell if it is leaking in a building. Mercaptan is added when it enters the distribution network; it is not added to all trunk lines, so a leak in a major pipeline could be odorless.

Transco started to add mercaptan at the northern end of its trunk line. By 2015, the added pressure from shale gas produced in the Marcellus/Utica formation of Pennsylvania/Ohio/West Virginia forced the "null point" in the Transco mainline from New Jersey to the south, where the system lacked ventilation and other facilities to deal with the odorized gas.

As part of its proposed Atlantic Sunrise Project and Leidy Southeast Expansion Project, Transco proposed to deliver more Marcellus Shale gas to Virginia and other Mid-Atlantic states. The Phase II Virginia Southside Expansion would upgrade compressor stations and other facilities to "odorize" that gas in Transco pipelines as far south as South Carolina. Dominion Resources proposed to built the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, and other investors proposed the Mountain Valley Pipeline, to bring natural gas south from fracking operations in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia.26

due to additional suppliess of natural gas from fracking in the Marcellus Basin, the Transco pipeline could deliver gas to power plants in Brunswick and Greensville counties from Pennsylvania/Ohio/West Virginia rather than from the Gulf Coast

Source: Williams Gas Pipeline Update & Strategies

In addition to breaks caused by corrosion in pipes after decades underground, pipeline leaks and explosions can also triggered by nearby construction projects that accidentally cut into gas pipelines (and other utilities). All regulated utilities in Virginia are required by the Virginia Underground Utility Damage Prevention Act to join the Virginia Utility Protection Service ("Miss Utility") system.

In addition to breaks caused by corrosion in pipes after decades underground, pipeline leaks and explosions can also triggered by nearby construction projects that accidentally cut into gas pipelines (and other utilities). All regulated utilities in Virginia are required by the Virginia Underground Utility Damage Prevention Act to join the Virginia Utility Protection Service ("Miss Utility") system.

Since 2007, anyone planning to dig underground can call 811. Owners of underground infrastructure - including the gas pipeline companies - get notified, and must mark the location of their facilities within three business days.27

In 2013, utilities such as Verizon and Virginia Natural Gas could contract with United States Infrastructure Corp (USIC), UtiliQuest, or S&N Locating Services to mark the locations. When excavators realize the marking is incomplete and their workers are exposed to potentially hazardous situations, they complain to the State Corporation Commission (SCC), which can impose fines on the three companies. According to the SCC, its efforts since the state agency gained enforcement authority in 1995 has resulted in a 68 percent decrease in damage to gas lines.28

The United States has constructed 3 million miles of gas pipelines to connect with over 77 million customers. As fracking expanded the supply, a second surge in pipeline expansion started in the second decade of he 21st Century:29

natural gas pipelines (blue) and oil pipelines (red) in Fairfax County

Source: US Department of Transportation, National Pipeline Mapping System, Public Viewer

interstate (red) and intrastate (blue) natural gas pipelines in Virginia

Source: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), EnviroMapper

Transco natural gas pipeline route through a portion of Virginia

(replacement pipe through Manassas Battlefield was installed in 2012, after Civil War Sesquicentennial events had concluded)

Source: Transcontinental Gas Pipe Line Company, Mid-Atlantic Connector Expansion Project

natural gas is supplied to houses east of Bull Run Post Office Road, in Fairfax County