the Roman fasces, shown on either side of the seat of the Speaker of the US House of Representatives, symbolized authority and the "bundle of rights"

Source: US House of Representatives, The House Chamber

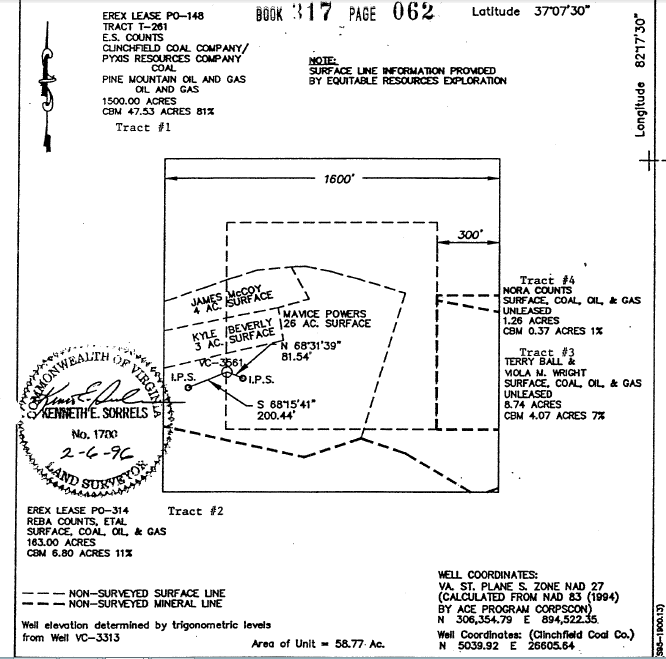

the Roman fasces, shown on either side of the seat of the Speaker of the US House of Representatives, symbolized authority and the "bundle of rights"

Source: US House of Representatives, The House Chamber

In the United States, property rights can be compared to a bundle of sticks. Owners of real estate can separate out some sticks from the bundle, such as the right to occupy a dwelling unit. One-third of Virginians contract with the owners of real estate for the right to occupy a house/townhouse. Through the rental contract, renters control some of the "sticks" in the bundle of rights, for the term of the lease.

Owners of forested land can sell the right to cut trees to a timber company, separating the ownership of the commercial timber from ownership of the land itself. Owners of rural land can lease their acreage to a farmer for a 10-year period, providing enough control over the land to incentivize the farmer to invest in fertilizer and ensure continued productivity. Most Virginia homeowners have a clause in their deeds, granting utility companies a perpetual easement (a property right) to install power lines across private property.

Property rights for underground minerals (such as oil, natural gas, coal, and coal bed methane) are based initially on surface ownership. When the colonial government first sold land to private property owners, all property rights transferred with the deed. Ownership of the surface and ownership of the minerals underneath the surface were united.

However, ownership of surface and mineral rights can be split. The right to mine coal can be sold separately from the right to cut timber, and the right to extract coalbed methane can be sold separately from the right to mine coal. (In 2004, the Virginia Supreme Court ruled that coalbed methane was a separate mineral from coal.)1

Before energy companies are willing to spend money on exploratory drilling, followed by development of infrastructure to produce coal/oil/gas, they acquire enough ownership rights to the subsurface resources. "Landmen" for the energy companies negotiate with landowners to purchase the rights to underground resources, while allowing those landowners to retain ownership of the surface for farming, forestry, and housing.

Prices for mineral rights vary, depending upon the potential value of the resource. In areas underlain by Marcellus or Utica shale, adjacent property owners may negotiate dramatically different deals with landmen, depending upon the interest of the energy developers and the sophistication of the landowner. Rights to disturb the surface in order to extract the resource through construction of roads, well pads, pipelines, etc. may also vary dramatically.

In many cases, leases for subsurface rights are never exercised. A landowner may receive a one-time payment for signing a lease, but get no royalties from production because the resource is never developed. Once a lease expires, the surface and subsurface rights are re-united and the landowner can sign a new deal for subsurface rights.

If the mineral rights are developed before the lease term expires, the lease remains in effect and royalties are paid until production ceases. Restoration of the disturbed areas on the surface has been required by state and Federal laws since 1977, but eroding piles of waste rock ("gob") still present on abandoned mine lands show how surface resources were not protected in the past.

coal refuse (gob) pile from abandoned 1950's mine in Russell County, eroding sediment into Clinch River watershed

Source: Virginia Cooperative Extension, Powell River Project - Reclamation of Coal Refuse Disposal Areas

The boundaries of oil and gas reservoirs are determined by geology, as hydrocarbons are generated at source rocks, mobilized by heat/pressure, and are trapped where bedrock characteristics (reduced permeability of "caprock" formations) block further migration. The oil and gas reservoirs do not match surface ownership property lines.

However, under the common-law "rule of capture," whoever drills a well and extracts oil or natural gas owns 100% of the hydrocarbons. A well drilled near a property line would suck gas from underneath adjacent properties, but according to the rule of capture the adjacent landowners would receive no compensation.

The rule of capture encourages each surface landowner to drill their own wells, well pads, and roads, leading to duplicative infrastructure and costly/inefficient development of a gas field. A more-logical pattern of development would space wells according to the underground geology, to tap into all of the resource at the least cost.

The alternative to the rule of capture is to define the underground boundaries of oil and gas fields, and establish drilling units with well spacing defined by the most effective design for extracting the underground resources. To ensure fairness, states that establish drilling units require that the value of the extracted oil/gas be shared with surface owners based on a formula (typically, percentage of surface ownership above the geologic resource). Revenues are "pooled" and then distributed based on the formula.

Getting every surface owner above a geologic unit to agree to sharing revenue (or even to permit drilling) can be difficult. Under Virginia's Gas and Oil Act of 1990, landowners can be forced to participate in a "pool" and lease their gas rights once a company has leased 25% of the acreage within a geographic area.

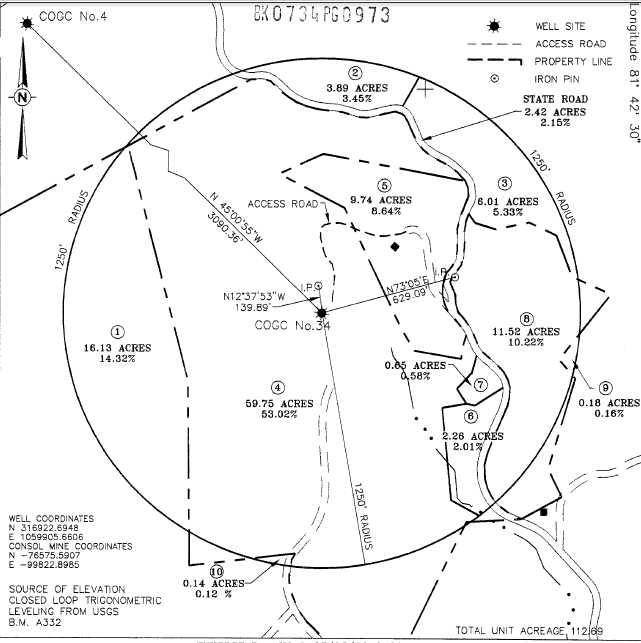

The Virginia Gas and Oil Board designates a drilling unit of land, and determines the most efficient spacing between wells within that unit. The board can require landowners to participate in a pool, but can not require the surface owner to allow a well pad to be constructed for drilling from the private surface. Each parcel of land in coal/gas country may have a complicated set of surface and subsurface ownership ("split estate") rights, and those determine how much the surface may be disturbed in order to extract underground resources.2

Forced pooling ensures efficient development of the resource, in contrast to the pre-1990 "rule of capture" approach that allowed a well to drain the gas from adjacent property without payment. Under the old approach, as soon as a well was drilled every adjacent landowner would have to drill their own wells - or watch their asset disappear. Energy companies feared lawsuits over the property rights, but passage of the Virginia's Gas and Oil Act in 1990 clarified ownership and spurred a surge in coal bed methane production.

The law resolved how to permit drilling in units of 60-80 acres, without giving every surface owner a veto that could block development. The Virginia Gas and Oil Board defines a drilling unit (i.e., an 80-acre square for coal bed methane wells, or perhaps a circular drilling unit for a conventional natural gas well), and forces all landowners within that drilling unit to allow drilling and extraction of the subsurface resource. If an owner objects to surface disturbance, directional drilling from a well pad on an adjacent parcel may be used to effectively drain the reservoir.

If some landowners refuse to sign leases with the driller, but the driller was able to get agreements with at least 25% of the mineral rights owners, then the Virginia Gas and Oil Board creates a "forced pool" and applies standard rules for determining how the royalties will be managed. Energy companies must offer the holders of mineral rights within the boundary of a forced pool drilling unit an opportunity to become a "participating operator," sharing in the costs of the drilling and in the resulting profits (or losses). Landowners almost always decline this opportunity, but drilling may still proceed and those landowners will still get a payment.

The state agency, the Virginia Gas and Oil Board, determines the percentage of the acreage within the drilling unit belonging to each landowner, and that percentage determines how much of the driller's "net proceeds" (profits, after production costs are deducted from sales) will be shared with the surface owners. In addition, the state agency establishes that landowners will receive an annual payment (such as $5/acre) for as long as the drilling unit is producing.

Drillers must deposit 12.5% of their profits into the Virginia Gas and Oil Board escrow fund for those landowners who did not choose to sign an agreement, multiplied by the percentage of land for which no agreements had been reached. For example, if the driller was able to reach agreements with owners of 90% of the mineral rights, then the driller must deposit 12.5% x 10% (a total of 1.25%) of net proceeds into escrow. If the driller was able to negotiate deals with only 50% of the holders of mineral rights, then the escrow deposit would be 12.5% x 50% (a total of 6.25%) of net proceeds.

Those landowners who did not sign an agreement must petition the Virginia Gas and Oil Board to receive their share. The ineffectiveness of the petition process, and the failure of the Virginia Gas and Oil Board to ensure full escrow payments and swift distribution to landowners, erupted as a scandal in 1999.

Landowners were not notified that royalties had been deposited and that it would be timely to petition for payment. Despite the 1990 law, the Board claimed it still needed a decision by a judge or an arbitrator, or a signed agreement between owners of mineral rights and the surface ownership, before distributing royalties.

The Bristol Herald Courier won a Pulitzer Prize for a 1999 series of articles exposing that administrative barriers blocked landowner access to royalties deposited into the escrow fund, and revealing an excessively cozy relationship between regulators/coal companies and mismanagement of the fund.3

Disputes over split estate ownership rights were not limited to just the failure of the Virginia Gas and Oil Board to distribute royalties. Surface landowners claimed that energy companies had misinterpreted the deeds to coal rights, and that the coal bed methane was not included in the right to extract coal. Based on that interpretation, energy companies were obliged to pay holders of mineral rights 100% of the value of the methane that had been extracted, not just a 12.5% royalty.

In 2004, the Virginia Supreme Court determined in Ratliff v. Harrison-Wyatt that a landowner who sold their rights to the coal had not sold their ownership of coal bed methane. The ruling meant that companies with a lease for mining coal were not automatically entitled to drill for coal bed methane. Many landowners would be entitled to 100% of the value of the gas removed from beneath their land, and energy companies would have to pay far more than the 12.5% already deposited into the escrow fund.4

In part because the stakes were so high, the ownership dispute continued for years even after that Virginia Supreme Court ruling. In 2010, the General Assembly passed a law codifying how the Oil and Gas Board should implement the 2004 Virginia Supreme Court decision, directing the Oil and Gas Board to assume surface landowners had retained rights to coal bed methane and distribute royalties to surface landowners unless contracts documented otherwise.

The 2010 legislation was then invalidated by a ruling by the Attorney General. That ruling was controversial in part because a staff lawyer in the Attorney General's office provided legal advice to oil and gas companies in their efforts to block landowners from filing class action lawsuits to force payments of $28 million in escrow by 2013, and in part because the Attorney General received substantial donations from energy companies in his 2013 race for governor.5

Two companies, CNX Gas and EQT Production, were the focus of the legal disputes regarding coal bed methane royalties. The companies claimed that they were paying appropriate royalties into the escrow fund and that Virginia (not the companies) was at fault for delaying payments to individual landowners. A Pulitzer-prize winning series of articles in the Bristol Herald-Courier revealed that the Oil and Gas Board had not audited accounts or required payments, so all required royalties may not have been deposited into escrow as required. Owners of coal bed methane might have been cheated if the gas companies had understated production, but the Oil and Gas Board had failed to conduct independent assessments to verify reports from those companies.

The claimants' capacity to pursue lawsuits against those energy companies was limited, because legal costs would be high and even a successful lawsuit would provide only a small payment to an individual property owner. Since Virginia did not allow class-action lawsuits in state courts to resolve the dispute, landowners partnered together to pursue a class action lawsuit in Federal court.

If successful, the legal costs could be minimized - so not surprisingly, the energy companies opposed certification of class-action lawsuits by the Federal courts. Forcing plaintiffs to sue separately, rather than consolidate their legal costs in a class action suit, limited the risk that the energy companies would be forced to deposit additional funds into the escrow account.6

A Federal District Court approved a class-action lawsuit in 2012, but the Fourth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals blocked that action in 2014 and returned the case to the District Court for further documentation of the "class." In 2015, the Virginia General Assembly passed a law that once again directed the Oil and Gas Board to release escrowed funds to landowners unless the energy companies objected by January 1, 2016. That state law (HB 2058) allowed landowners to collect royalties already paid by the gas companies, but still sue the gas companies to collect additional royalties.7

Natural gas can be stored underground in caverns excavated in salt formations. Gas companies who do not own land in fee, with all of the "bundle of rights," can acquire storage rights from surface owners. Compared to building large tanks on the surface, underground storage is cheaper for pipeline companies needing to store a supply of natural gas for the peak demand in the winter.

In Texas, a company seeking to store hydrocarbons underground claimed that its ownership of the underground salt for removal also conveyed ownership of the cavity created by mining. That cavity had value as a storage site for oil and gas.

Texas courts ruled that the surface landowner had transferred ownership of only the salt. A hole deep underground was not salt, and the surface owner retained ownership to the hole after transferring rights to just the salt.8

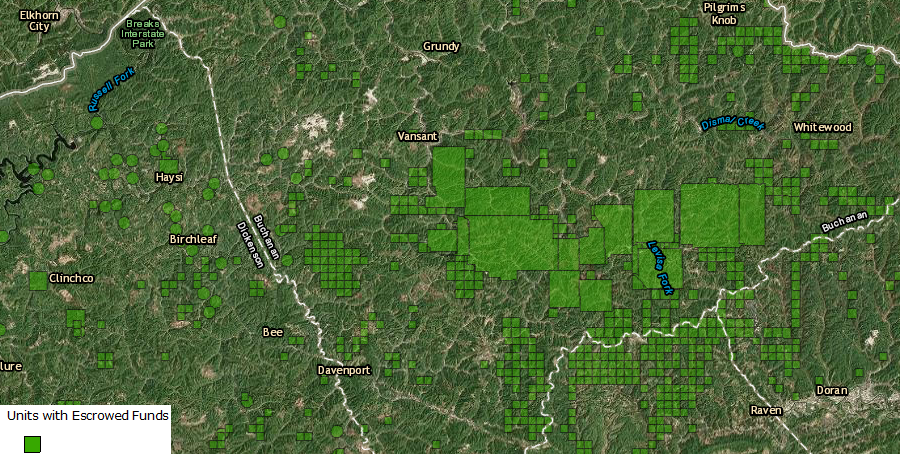

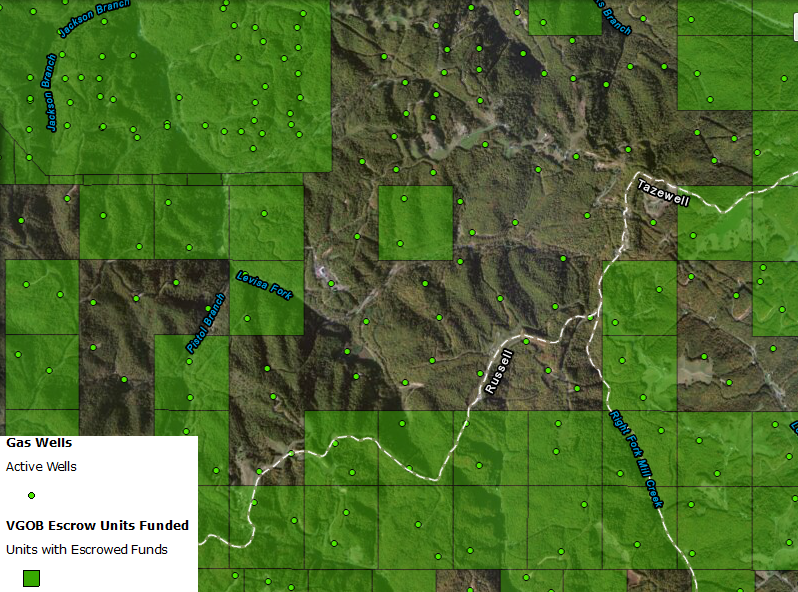

some - but not all - gas wells in southwestern Virginia have been included in pooling units, with royalties deposited into escrow accounts

Source: Virginia Department of Mines Minerals and Energy (DMME), Virginia Gas Escrow Unit Viewer