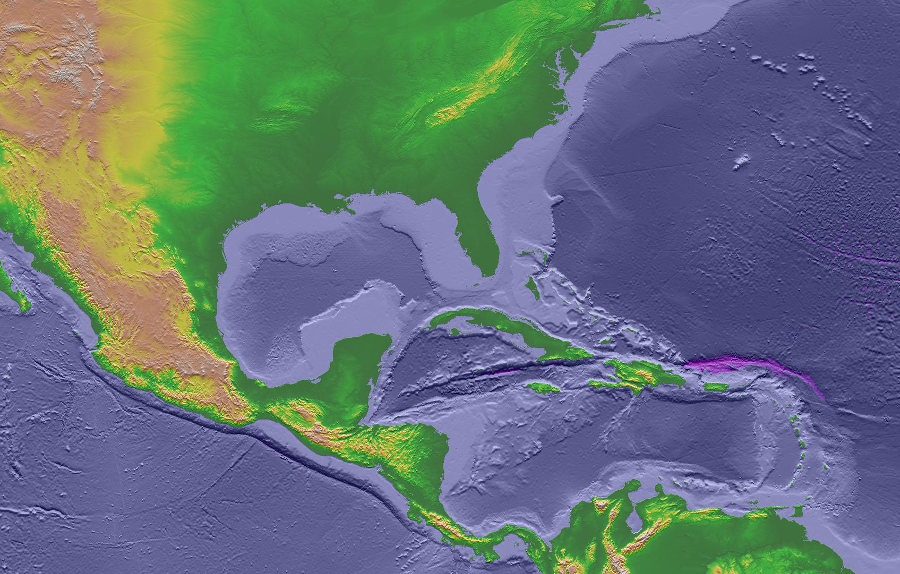

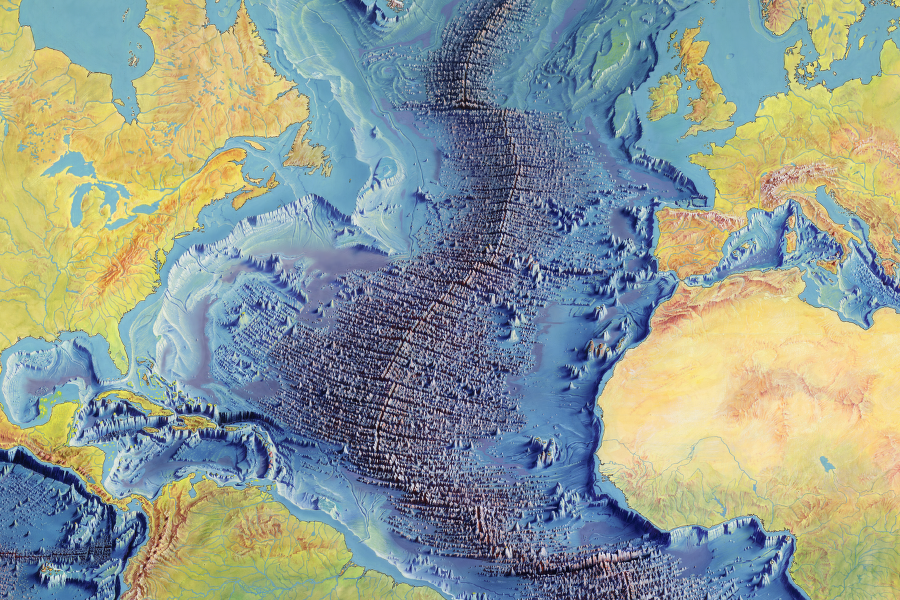

Virginia's eastern edge extends underwater across the Outer Continental Shelf

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, GLOBE: A Gallery of High Resolution Images

Virginia's eastern edge extends underwater across the Outer Continental Shelf

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, GLOBE: A Gallery of High Resolution Images

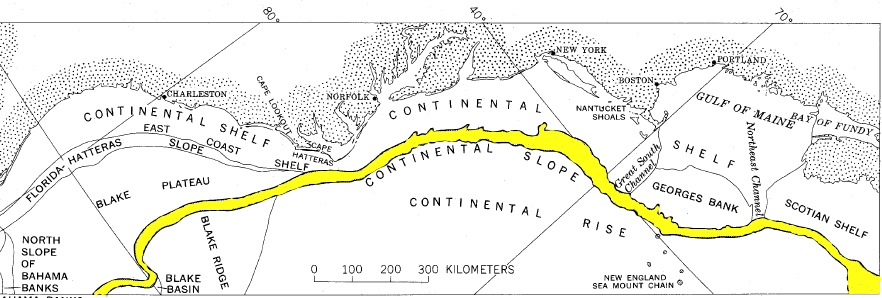

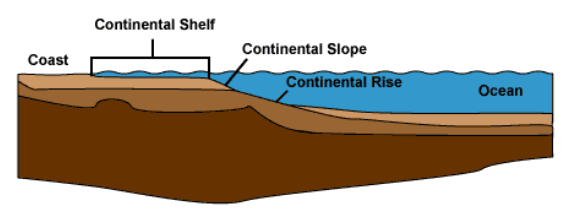

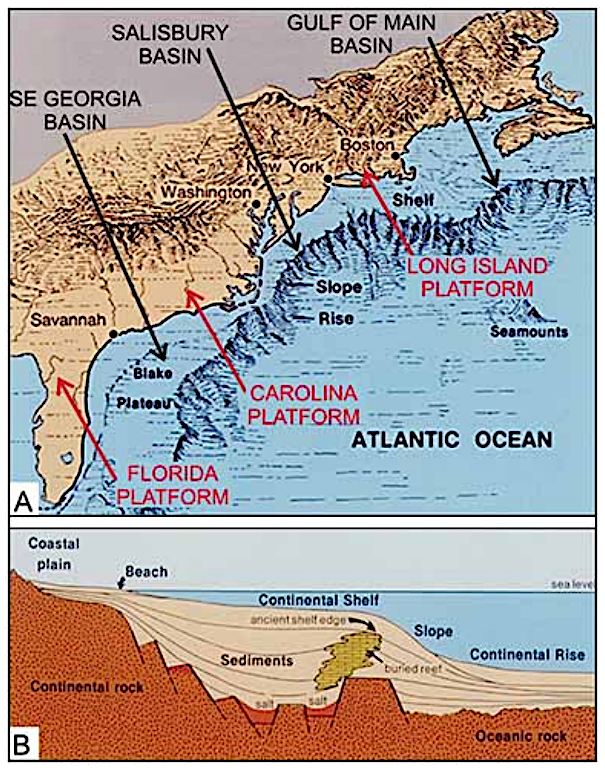

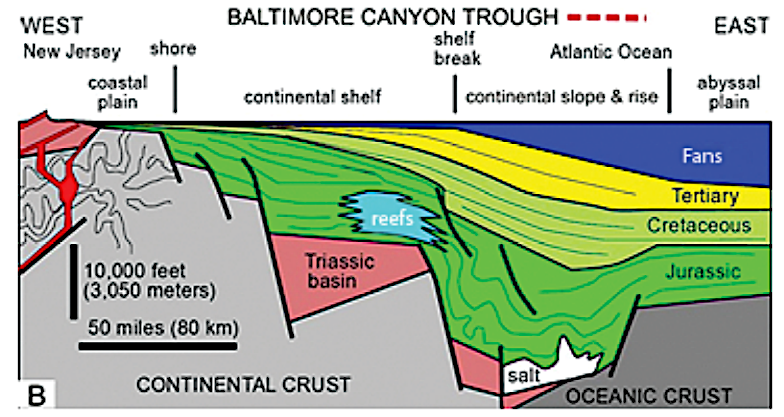

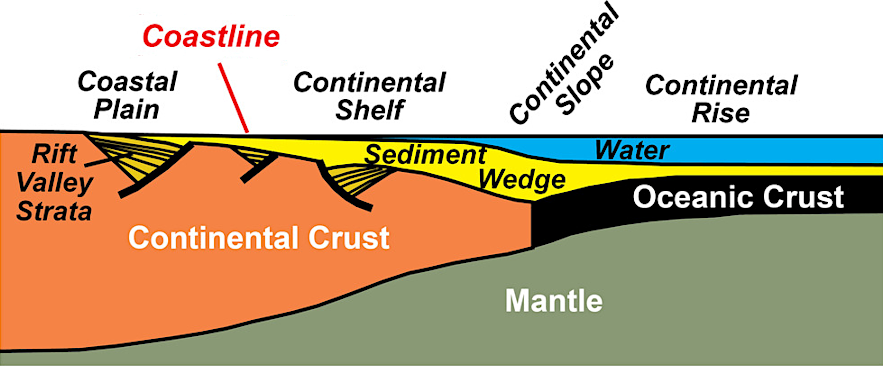

A portion of the continental crust which forms the North American plate is submerged around the margins of the plate now. Sea level changes over the last 250 million years have exposed and submerged various percentages of the continental shelf.

the bedrock of the continental shelf is relatively light continental crust, compared to the heavier basalt that forms the bottom of the oceans

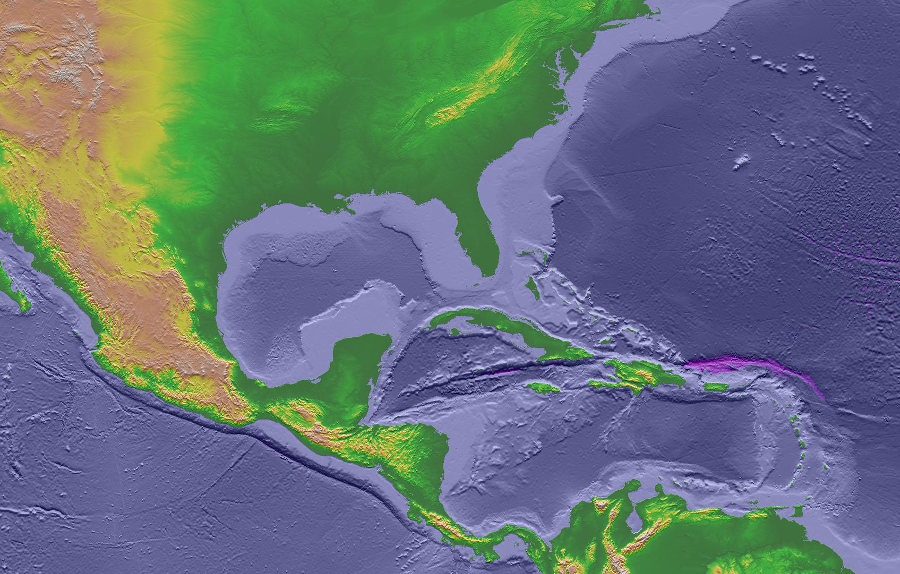

Source: National Park Service, Shaded Relief Map of North America and Continental Shelf

By the time Europeans arrived in Virginia, the Atlantic Ocean coastline was marked by marshes and barrier islands on the Eastern Shore and wide sandy beaches south of the Chesapeake Bay. The sailors understood the shoreline was dynamic. New spits of sand could appear after hurricanes, and dangerous new shoals could be created underwater when storms moved the sand. However, it is only recently that we have developed a clear understanding of how much the Virginia coast has changed over time.

The Continental Shelf and a portion of the current Coastal Plain were underwater 120,000 years ago, when sea levels were 20-25 feet higher. At the start of the Wisconsin glacial stage, the Laurentide ice sheet grew, trapping water on land. Sea level dropped and the Virginia coastline migrated to the east, exposing the sediments coating the former ocean bottom.

It was not a steady, constant change every year; the ice sheet grew and sea level dropped in distinctive steps. At times the process reversed and sea level rose briefly to drown the land again, with one such "transgression" occurring 35,000 years ago. About 30,000 years ago, the last step was a rapid expansion of the ice sheet and equally-rapid drop in sea level, exposing the last wedge of sediments that had been deposited on the outer edge of the Continental Shelf.1

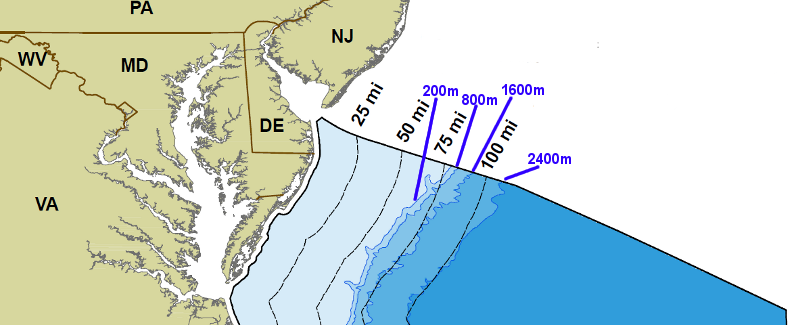

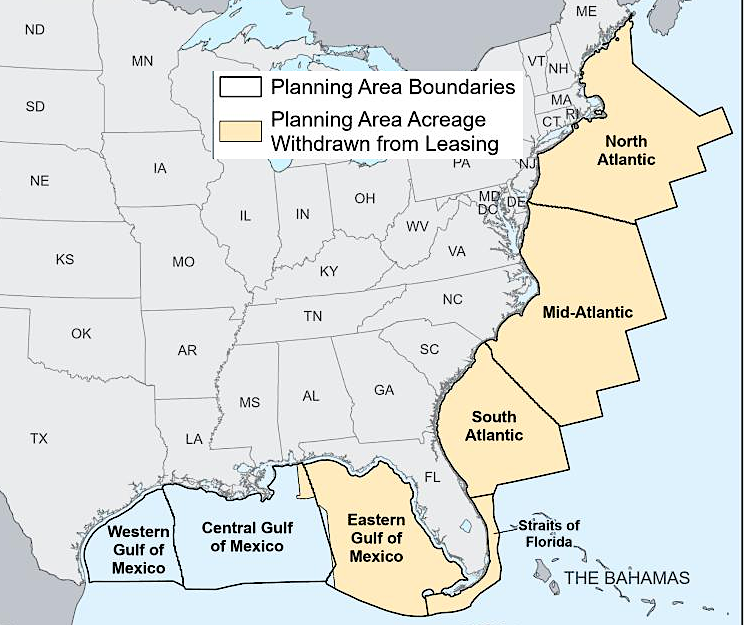

Outer Continental Shelf (in light blue)

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Marine Geology & Geophysics

When the first Virginian's arrived perhaps 20,000 years ago, sea levels were 300-400 feet lower because so much water was locked up in the glaciers and continental ice sheets. The Coastal Plain of Virginia extended much further to the east, where sloping hills and cliffs marked the edge of the land and ocean. Discovery of the original campsites of the first Virginians may require using submersibles to support underwater explorations and excavations.

The Cinmar bipoint was dredged up from the Outer Continental Shelf, 250 feet deep off the coast of Virginia, in 1970. That point had been flaked skillfully from a chunk of volcanic rock (rhyolite) whose original source was South Mountain in modern-day Pennsylvania. The Cinmar bipoint could be dated because it was dredged up together with a mastodon skull that was roughly 25,000 years old.

If that date is accurate (the point was not directly lodged in the skull when the scallop dredger pulled the items from the haul...), then early human settlement in Virginia extends far back in time, when the coastline was 40 miles further to the east. Those humans were crafting bipoints long before the Clovis style was adopted.2

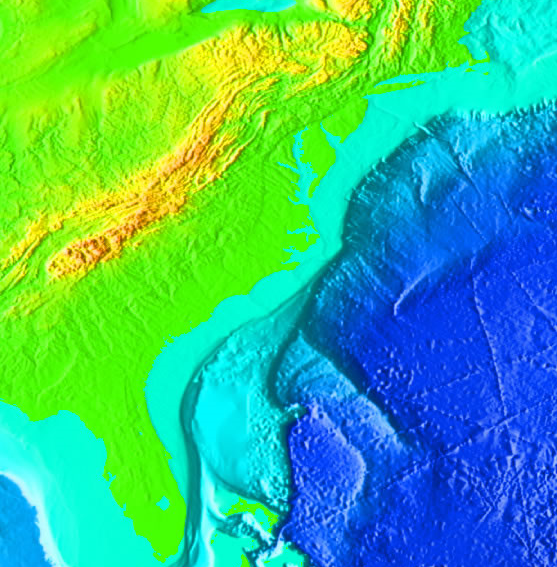

today, Gwynn's Island Museum is 85 miles from the edge of the Continental Slope

Source: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, MarineCadastre.gov National Viewer

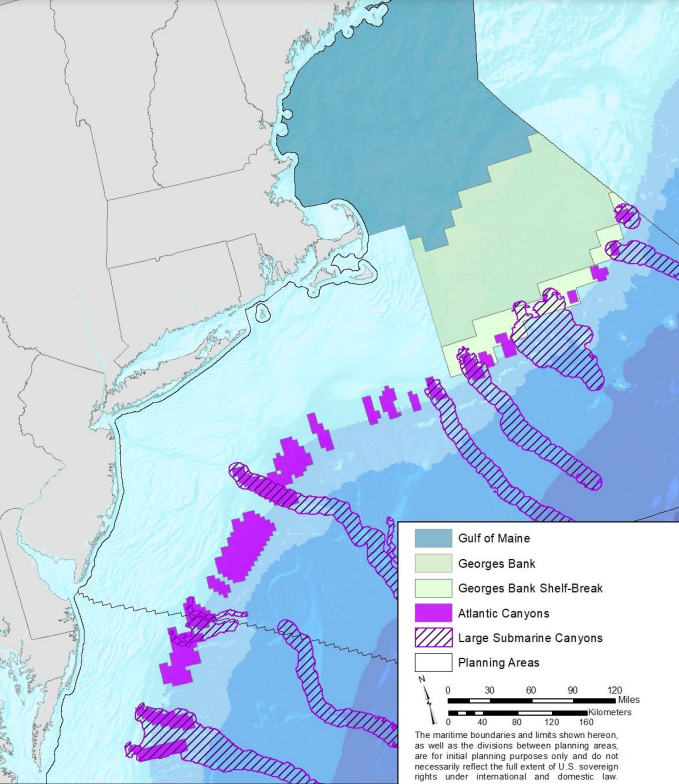

Rivers flowing off the Appalachian Mountains dug paths into the newly-exposed Continental Shelf as water levels in the ocean dropped from its last peak, at the start of the Wisconsin Ice Age. The Potomac and James rivers carved separate valleys across the wide Coastal Plain to the salt water, and there was no Chesapeake Bay.

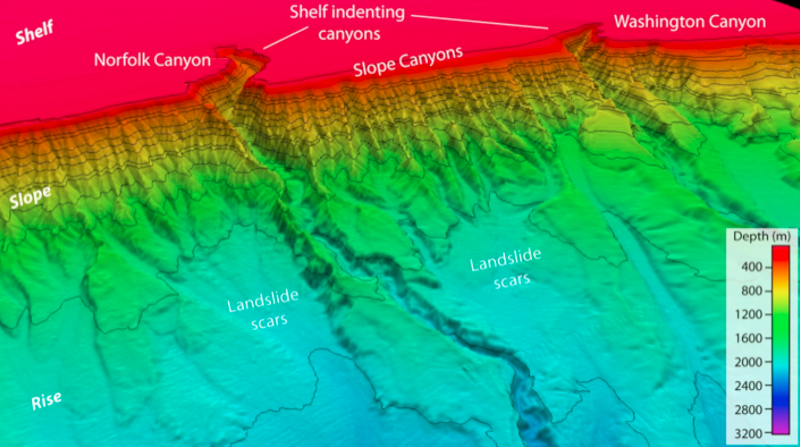

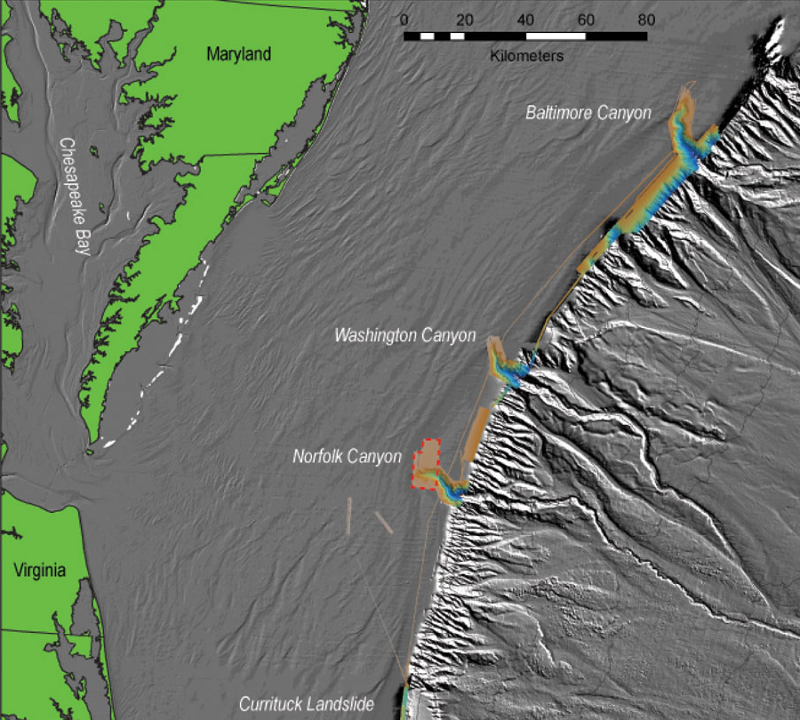

The most powerful rivers carved channels even through the Continental Slope (Rise), and massive landslides reshaped the cliffs between the canyons. The ancestral Susquehanna River may have carved the Washington Canyon. The Potomac, Rappahannock, and York Rivers may have combined to etch out the Norfolk Canyon - perhaps with the help of the James River. It is also possible that the Susquehanna River is responsible for the erosion scar now called the Norfolk Canyon.3

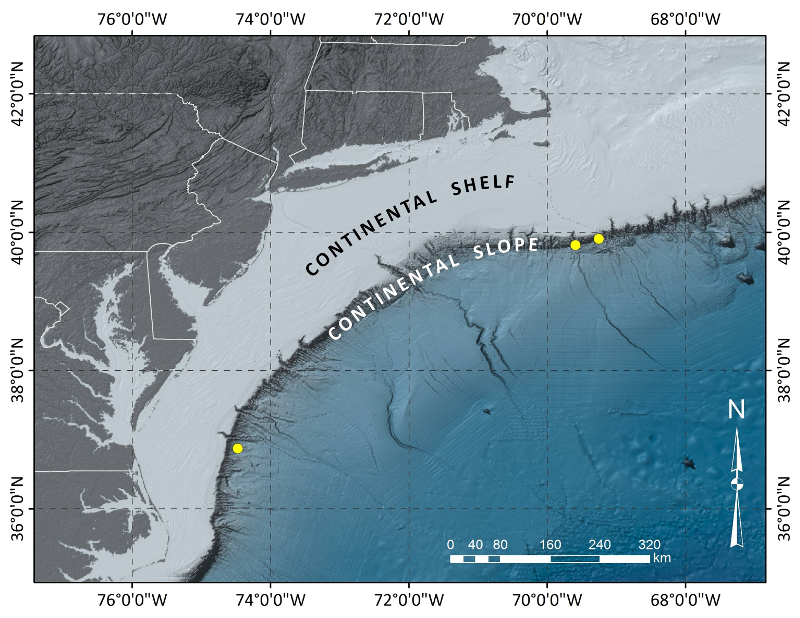

canyons on the edge of the Continental Shelf show former river channels of Pliocene/Pleistocene age

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Deep-Water Mid-Atlantic Canyons Exploration 2011

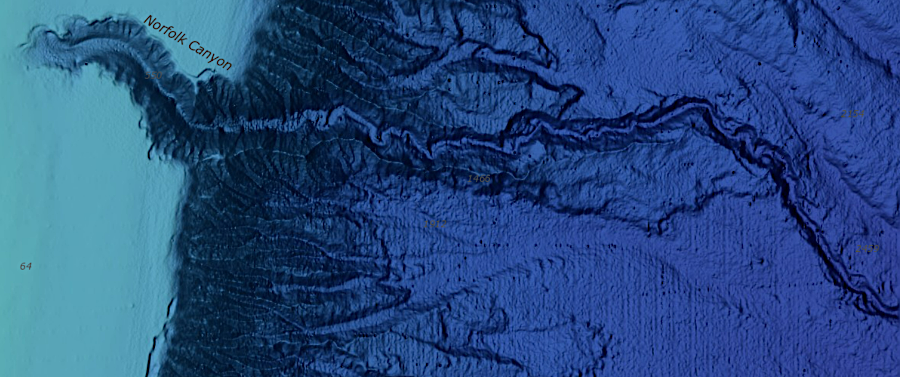

Norfolk Canyon was etched into the edge of the Continental Shelf when sea level was as much as 400 feet lower

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Bathymetric Data Viewer

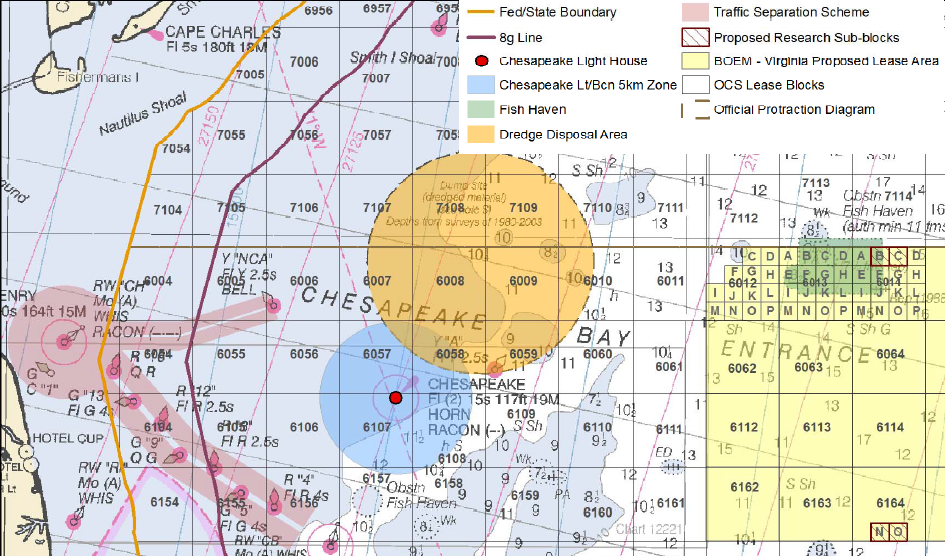

The ancient, separate river valleys of the Susquehanna and James rivers remain today at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Drivers crossing the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel go underwater at two locations shaped by those rivers, in a tunnel under the James River channel (Thimble Shoals) and further north in a tunnel underneath the old path of the Susquehanna River (Chesapeake Channel).

contour lines showing depth of Outer Continental Shelf (in blue) and distance from Virginia shoreline (in black)

Source: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation, and Enforcement, 2006 National Assessment Maps - Undiscovered Technically Recoverable Oil & Gas Resources

Much of the Coastal Plain that existed 18,000 years ago has been drowned by the rising Atlantic Ocean. The first people who arrived in Virginia witnessed rising sea levels drowning the eastern edge of the Coastal Plain, creating today's Continental Shelf between the current Atlantic Ocean shoreline and the cliffs of the Continental Slope. We still witness sea level rise today, gradually altering the outline of the Chesapeake Bay and continuing to widen the extent of the Continental Shelf.

Outer Continental Shelf, Slope (in yellow), and Rise

Source: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation, and Enforcement, Environmental Report: Use of Federal Offshore Sand Resources for Beach and Coastal Restoration in New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, and Virginia (November 1999)

The development of submarines, starting in World War I, increased our capacity to map the seafloor. Today we know:4

Outer Continental Shelf

Source: Department of the Navy, Ocean Floor - Continental Margin & Rise

canyons eroded into Continental Slope (paleoriver channels) when sea levels were lower

Source: US Geological Survey High-Resolution Multibeam Mapping of Mid-Atlantic Canyons to Assess Tsunami Hazards

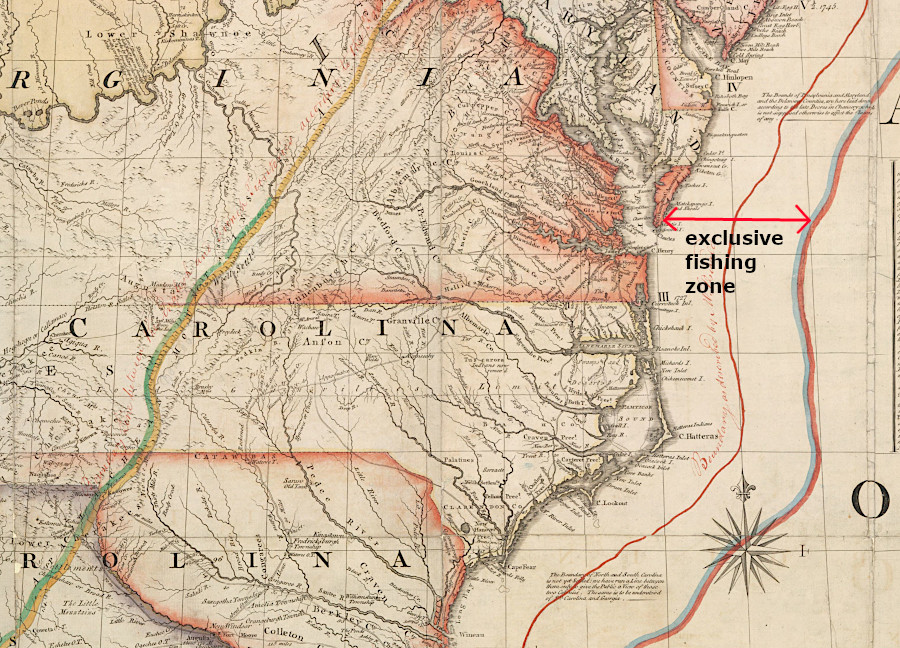

In the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht ending the War of Spanish Succession, Great Britain negotiated successfully for exclusive fishing rights off the coast of North America. France retained the right to fish only off the northern shore of Newfoundland. Otherwise, Great Britain was granted an exclusive fishing zone along most of the coast "extending 30 Leagues from the land" or 104 miles wide.

claims to exclusive offshore rights date back to at least 1713, when Virginia was still a British colony

Source: Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library, A Map of the British Colonies in North America (by John Mitchell, 1775)

Developing the mineral resources below the ocean became technologically feasible in the middle of the 20th Century, greatly increasing interest in the Continental Shelf. Geological investigations revealed that onshore oil fields clearly extended past the coastline, and oil companies sought to build platforms for offshore oil wells. Starting in 1937 state/Federal governments debated whether state or Federal government agencies could grant drilling permits and collect royalties from offshore oil wells.

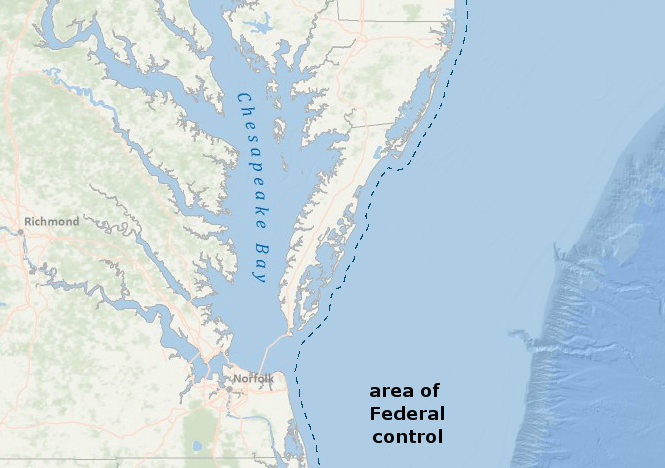

In 1947, the Supreme Court ruled that the Federal government could control development of offshore mineral resources. The decision established that sovereign rights over the seabed and ocean were acquired by the national government when it replaced the power of the king/Parliament after the American Revolution. According to the Supreme Court, the first 13 colonial governments had not acquired ownership of the seabed through their charters from the king in England, so at the start of the American Revolution the 13 original states did not inherit control over the seabed.5

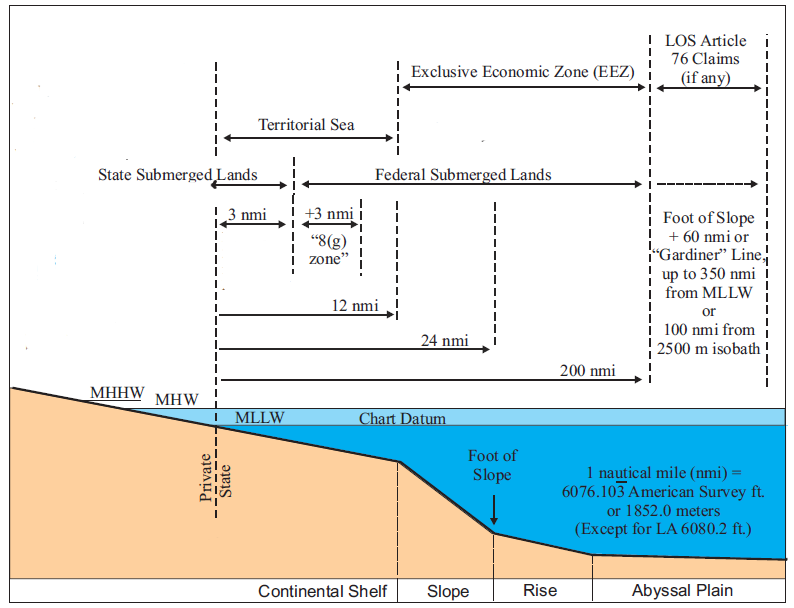

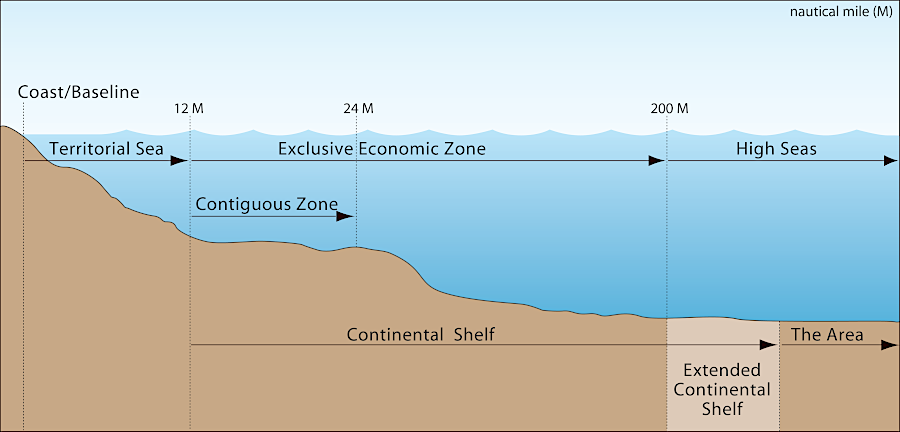

To resolve the controversy over control of oil underneath the tidelands (i.e., land covered by water near the shore), Congress passed the Submerged Lands Act in 1953. That law granted coastal states control over the bottom of the ocean for three nautical miles offshore, with the exception of 9 nautical miles for Texas and the west coast of Florida.

The 1953 law also confirmed state ownership of "all lands permanently or periodically covered by tidal waters up to but not above the line of mean high tide." Back in 1819, however, Virginia's General Assembly granted shoreline property owners ownership down to the Mean Low Water line, but that decision does not affect the determination of the Federal/state boundary three nautical miles offshore.6

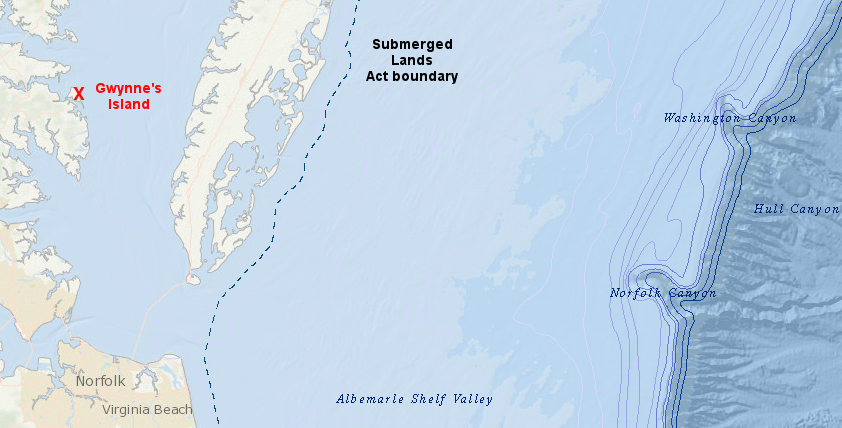

three mile boundary marking state/Federal control of Outer Continental Shelf

Source: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation, and Enforcement, Multipurpose Marine Cadastre

Defining the boundary three miles offshore requires defining the shoreline itself. However, the ocean-land interface is constantly shifting; the shoreline is not a static line. The Submerged Lands Act measured the line of state/Federal jurisdiction from the "coast line," defined as:7

In 1953 Congress also passed the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Land Act, endorsing the national government's claim to the ocean resources issued originally by President Harry Truman.

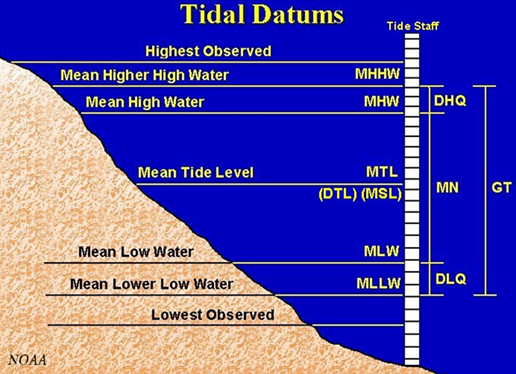

The Department of the Interior determines the boundary of Federal/state jurisdiction, when defining parcel boundaries for leasing OCS resources such as sand, heavy minerals, and especially hydrocarbons (oil and gas). The Department has adopted the mean lower low water (MLLW) line, as drawn on National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) - National Ocean Service nautical charts, as the coast line. NOAA uses the average of the lower low water height of each tidal day to draw the mean lower low water or MLLW line.

Because the boundary changes as storms, currents, or even construction projects reshape the shoreline, the Federal government is partnering with the states to adopt a fixed set of geographic coordinates to "immobilize" the boundary, eliminating future changes and minimizing confusion regarding jurisdiction.8

mean lower low water (MLLW) is below Mean Sea Level (MSL), so the boundary between Federal-state jurisdiction defined by the Department of the Interior extends slightly further offshore and states have a claim to a slightly-larger acreage of submerged lands

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Tidal Datums

More legal wrangling was required after 1953 to clarify the relative power of the states/Federal government over the Outer Continental Shelf, beyond the 3 nautical mile limit. In United States v. Maine, Virginia claimed that its colonial charters granted the state exclusive jurisdiction of Atlantic Ocean resources for 100 miles beyond the coastline.9

The US Supreme Court rejected that claim in 1975, affirming state control over the "inner" Continental Shelf and Federal authority over the Outer Continental Shelf out to the edge of the Exclusive Economic Zone, 200 miles offshore.

International claims of rights to control navigation, fishing, and economic development of mineral resources led to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. International standards for ocean boundaries are established in an international treaty. President Clinton signed the Convention on the Law of the Sea treaty in 1994, after it was modified to resolve President Reagan's concerns regarding international controls on deep sea mining of polymetallic (iron/manganese) nodules. However, Senate approval is required to finalize the US commitment to the treaty.

Congress has never ratified it, declining once again in 2012 due in part to concerns that the International Seabed Authority could limit US sovereignty. The International Seabed Authority is headquartered in Kingston, Jamaica, and is not part of the United Nations. It is responsible for developing regulations and issuing permits for seabed mining, while also protecting sensitive deepwater ecosystems. Only nations which have signed the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea may apply for permits.

One commentator has suggested that economic development will receive priority, especially if multinational mining companies get small nations desperate for revenue to apply for permits:10

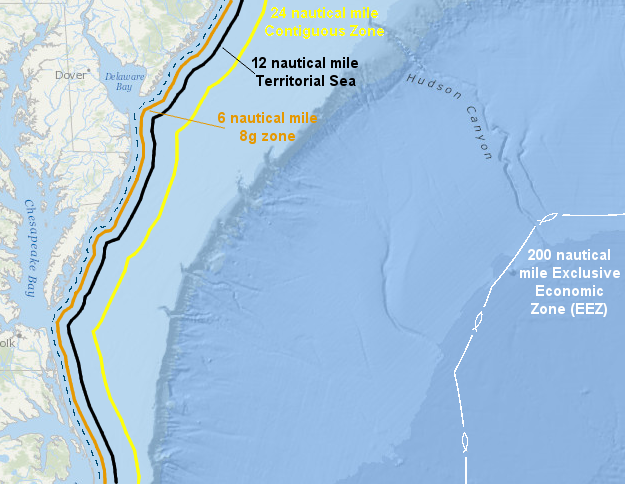

Consistent with the treaty (even though Congress has not ratified it), the United States claims a Territorial Sea for 12 nautical miles offshore. The starting point for defining offshore vs. inland waters is the "baseline," defined by the US as the line of mean low low water (MLLW) as mapped on the most-detailed (large scale) NOAA nautical charts.11

The US exercises sovereignty over its Territorial Sea, the air space above it, and the seabed and subsoil beneath it, but foreign-flag ships enjoy the right of innocent passage. The Federal government also claims a Contiguous Zone out to 24 miles (12 miles further than the Territorial Sea), allowing enforcement of federal customs, fiscal, immigration, and sanitary laws (but otherwise the US does not exercise sovereignty in the Contiguous Zone). Finally, the US claims an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extending from 12-200 nautical miles offshore, with exclusive rights to develop and manage marine resources - including energy and mineral resources on the seabed, such as oil/natural gas and iron/manganese nodules.

significant offshore boundaries beyond the three mile boundary

Source: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation, and Enforcement, Multipurpose Marine Cadastre

While the Federal government claims full ownership of lands outside the state claims, in 1986 Congress created the Revenue Sharing Boundary in section 8(g) of the OCS Lands Act amendments so the Federal government will share a "fair and equitable" portion of offshore revenues. The 8(g) Zone extends 3 miles beyond the state waters, and the Federal government gives coastal states 27% of revenues from oil/gas and renewable energy leases (i.e., offshore wind turbines) located in the 8(g) Zone.12

the Commonwealth of Virginia owns submerged land three miles offshore (red line), and the 8(g) zone for revenue sharing is six miles offshore (orange line)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

NOAA has rules with complicated mathematics involving equidistant arcs that guide how to map the baseline between headlands and across the mouths of rivers, bays, and estuaries. The baseline is dynamic ("ambulatory"), subject to change due to accretion and erosion of the shore. Permanent structures built on the shoreline, such as jetties, groins, and breakwaters, can alter the baseline. Such structures can extend the US determination of the EEZ further into the ocean, and extend state control as well based on the Submerged Lands Act. Altered baselines affect how revenues from offshore oil/gas and sand mining operations are distributed, and can change responsibility for whether state or Federal agencies can authorize offshore wind towers.13

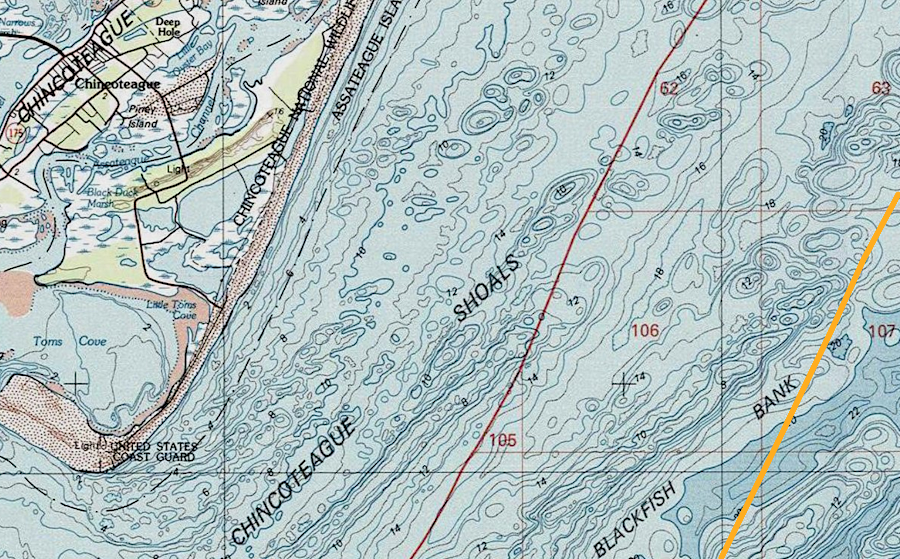

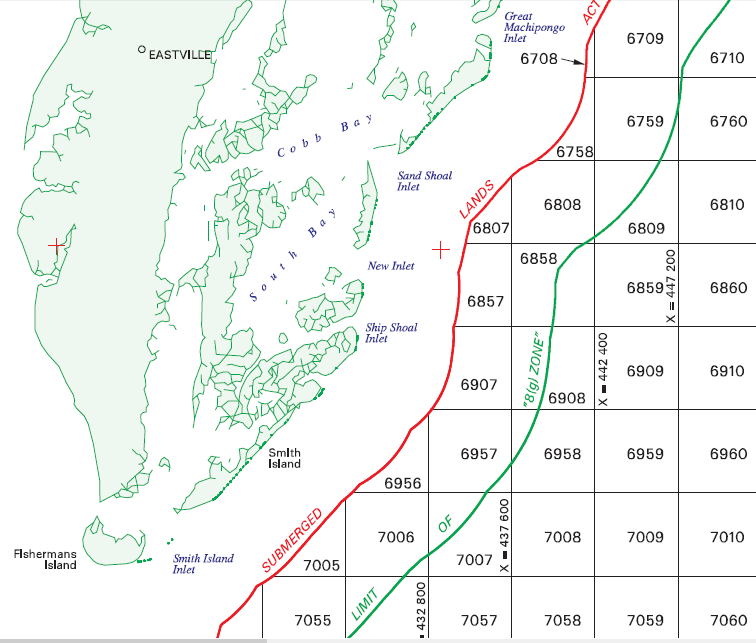

protraction diagrams defining blocks of territory for offshore leasing by Federal government

Source: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Atlantic Cadastral Data - NJ18-08 Chincoteague

Therefore, Virginia could receive 100% of lease bonuses, rents, and royalties of any petroleum leases issued within 3 miles of the coastline, which the state would authorize. For leases between 3-6 miles off the coast, Virginia would be entitled to 27% of any lease bonuses, rents, and royalties for leases issued by the Federal government. Beyond 6 miles, however, the Federal government would receive all revenues associated with easing submerged lands on the Outer Continental Shelf.

The various ownership boundaries migrate as the shoreline changes. As sea level rises and the Virginia shoreline recedes westward, the boundary between state/Federal waters will move as well. Royalties and regulatory authority for offshore wind turbines or oil/gas wells could be affected in the future, if boundary shifts cause state-approved facilities built within three nautical miles of the coastline to end up in Federal waters.

As noted by the Office of Coast Survey in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA):14

OCS boundaries

Source: based on graphic at Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation, and Enforcement, Marine Boundaries

The Unites States first asserted a claim to own the seabed offshore in 1945. President Truman wanted to limit Japanese ships from catching salmon off Alaska and to prevent other nations from extracting oil and gas for near the American coastline. The first UN Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1958 discussed how to authorize nations to control portions of the Outer Continental Shelf. It adopted a the U.N. Conventions on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS I), and a 1960 convention adopted a revised UNCLOS II.

In 1970, 108 nations - including the United States - agreed that the ocean floor was the "the common heritage of mankind." The Nixon Administration supported creating an International Seabed Authority to manage the shared assets. However, the United States policy shifted during Reagan administration. In 1982, the current Law of the Sea treaty (UNCLOS III) was adopted.

One of four countries to reject the treaty was the United States. As described by the Reagan Administration, it was inconsistent with the concepts of economic liberty and free enterprise. At the time, the United States had the lead in the technological capacity to extract mineral resources from international waters. Because the United States has never signed the Law of the Sea treaty, it is not obligated to pay royalties for resources extracted from the seabed to the International Seabed Authority.

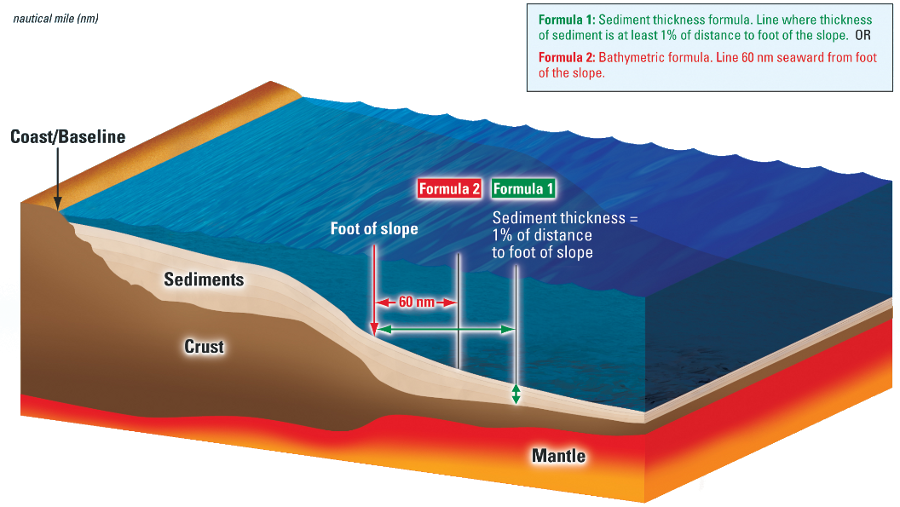

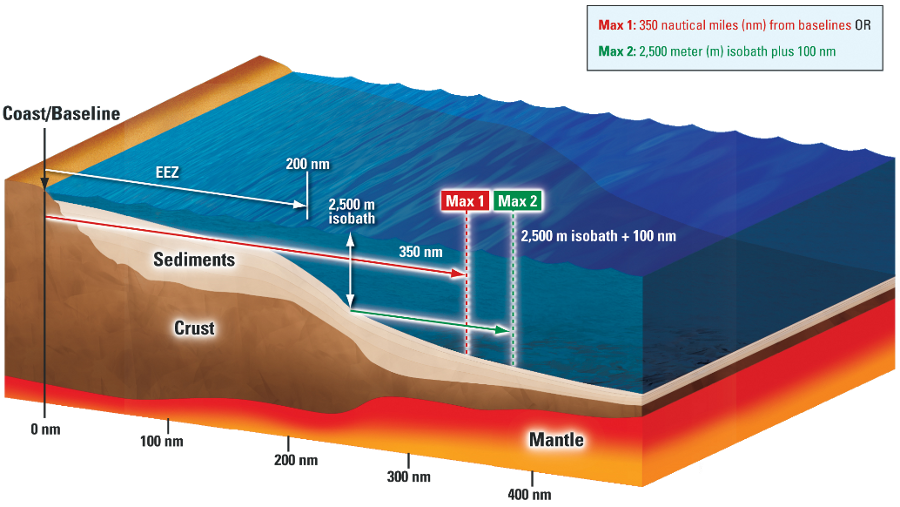

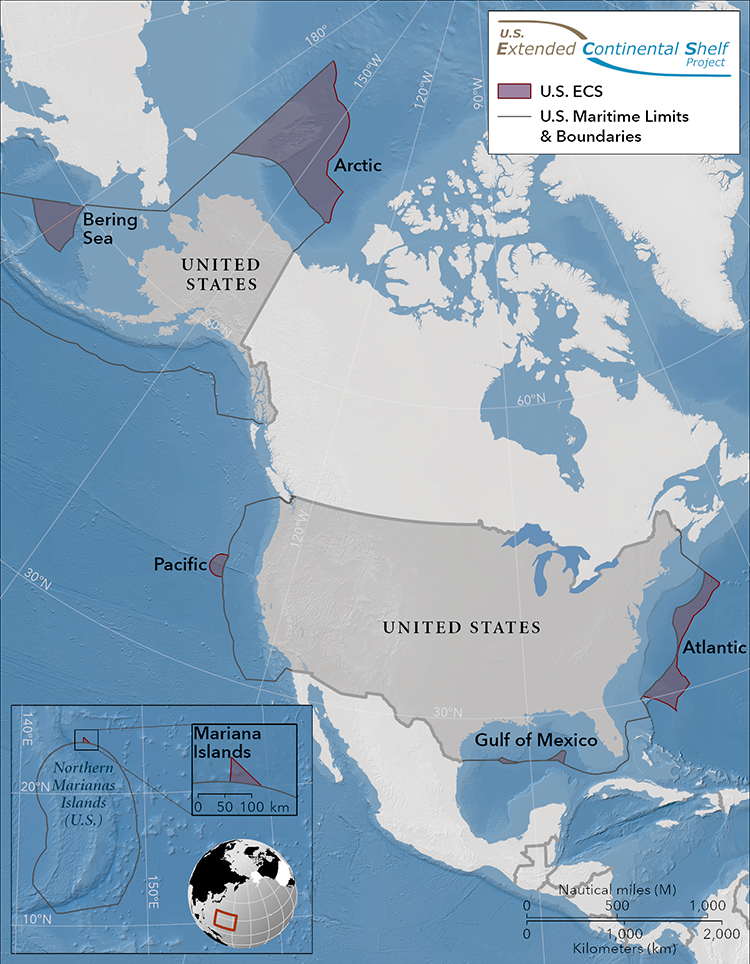

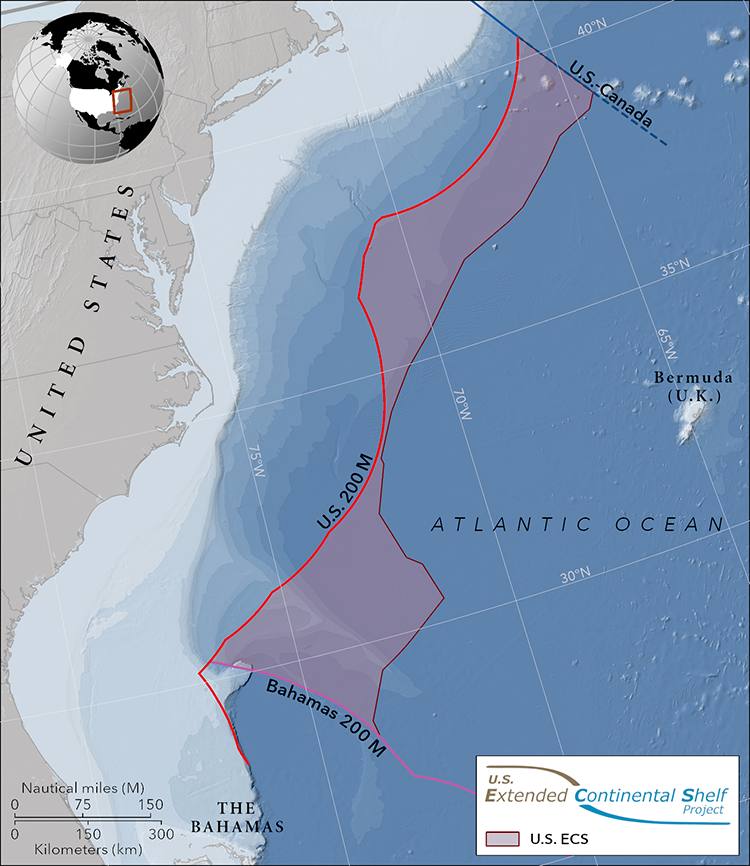

the Law of the Sea allows a nation to define the boundaries of the Outer Continental Shelf beyond the 200 mile limit of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)

Source: Extended Continental Shelf Project

boundaries of the Outer Continental Shelf may not extend beyond "constraint lines" defined by the Convention on the Law of the Sea

Source: Extended Continental Shelf Project

On December 19, 2023 the Department of State extended the United States claim beyond the 200 nautical mile limit of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The claim was based on Article 76 in the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III) and to prevent other nations from extracting oil and gas for near the American coastline, even though the United States has not ratified that treaty.

The United States made a unilateral announcement claiming its inherent rights, rather than make a submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf for confirmation of the claim by other nations. The US claims overlap claims made by Canada, the Bahamas, and Japan.

The treaty allows a nation to assert exclusive rights to the Outer Continental Shelf extending as much as 350 nautical miles east of the shoreline, based on the location of the foot (bottom) of the Continental Slope. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) spent 20 years collecting bathymetric and seismic data needed to define extended continental shelf claims, based on Article 76.

Particular effort was focused on the Arctic Ocean where Russia, Canada, and the United States have overlapping claims. Following the US claim, fiver Arctic nations have established national boundaries and very little of the Arctic Ocean remains as international seabed to be controlled by the International Seabed Authority. The boundaries of the US-Russian claims to the Arctic seabed were defined in the 1990 Agreement between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Maritime Boundary. The US Senate ratified that treaty, but the Russian Duma (which inherited the claim after breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991) has not.

The Department of State also asserted ownership to parts of the Outer Continental Shelf beyond the 200 mile Exclusive Economic Zone in the Bering Sea, Atlantic Ocean off the East Coast, Pacific Ocean off the West Coast, near Mariana Islands, and in two areas of the Gulf of Mexico.15

in 2023, the Department of State announced extended continental shelf claims of the United States

Source: Department of State, Maritime Zones, U.S. Extended Continental Shelf

Responsibility for the land and water off the Virginia coast is split between the state and Federal government. Virginia controls the first three miles offshore, based on the authority in the Submerged Lands Act in 1953. Between 3-200 miles, the Federal government is responsible for resource management and will determine if windmills, subsea dredging/strip mining for mineral nodules, or oil drilling platforms will be permitted on the Outer Continental Shelf.

Federal agencies issue permits for species harvest and mineral extraction, beyond state waters, to the limit of US claims. For example, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, a part of the Department of the Interior, is responsible for offshore leasing outside of state waters.

Migratory fish are managed by the National Marine Fisheries Service, part of National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA). The Federal agency sets harvest limits and ensures compliance in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) outside of state waters, after coordination with Virginia and six other coastal states that belong to the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council.

Virginia controls fishing and mining for three miles offshore, but uses interstate and federal partnerships to synchronize species and ecosystem management. To manage migratory fish, crabs, and oysters in the Chesapeake Bay, Virginia must focus on cooperation with just one state - Maryland. To manage migratory species in state waters in the Atlantic Ocean, however, 15 Atlantic Coast states have partnered to create the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. That organization adopts interstate fishery management plans for species within state waters (within the 3-mile limit) along the East Coast.

Virginia is not a member of the South Atlantic Marine Fishery Council, but considers requests from that organization. In 2016, that council proposed closing the cobia fishery on June 20 to protect the species from overharvest. The Federal government concurred, blocking cobia harvest from waters more than three miles offshore. The Virginia Marines Resources Commission, the state agency responsible for managing salt-water fisheries within three miles of the coast, chose to keep the cobia fishing season open until August 30, but limited the number of fish that anglers and boats could catch.16

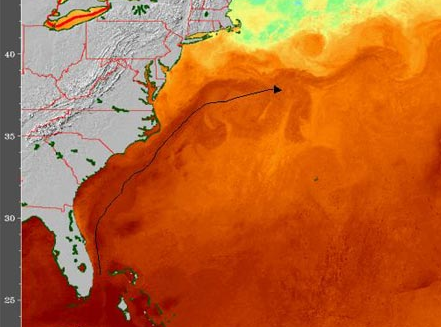

the warm Gulf Stream affects what lives on the ocean bottom and in the water column above the Outer Continental Shelf

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Ocean Explorer

Potential development of offshore oil and gas resources (including gas hydrates) in the Federal portion of the EEZ have generated great interest. The Federal government defined potential lease area on the OCS for multiple Federal oil and gas leases. Governor McDonnell strongly advocated for making Virginia the "Energy Capital of the East Coast."

The governor did not have authority to lease hydrocarbons more than three miles from the coast, where the sedimentary basins may have trapped commercial quantities of natural gas. A Federal agency in the Department of the Interior prepares the 5-year schedule of oil and gas lease sales. No recoverable reserves of oil and gas are thought to be within the three-mile limit, limiting the ability of the governor to spur development of petroleum resources, but Virginia has approved offshore wind energy platforms within state waters.

2012 proposed Federal wind energy lease area (green blocks) is far offshore, but transmission line carrying electricity to the mainland would run though 8g) and state-owned submerged lands

Source: Department of the Interior - Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Map of the Area Proposed for Leasing in the Virginia Proposed Sale Notice (PSN)

In 2012, the Federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management announced plans for leasing a 112,799-acre parcel on the OCS for commercial wind power. The proposed lease area stretched from 23.5-36.6 nautical miles east of Virginia Beach, but any transmission line carrying electricity to the mainland would run though 8g) and state-owned submerged lands. Under the proposed terms of the Atlantic Wind One (ATLW1) sale, the winner of the lease would have to pay $3.00 per acre annually for the leased acreage, $70.00 per statute mile for the transmission line, and an annual operating fee based on the amount of electricity generated.

Dominion Power won the bid in 2013. It delayed development of an offshore wind farm until the General Assembly passed legislation in 2018 that directed the State Corporation Commission to approve the expense. It then proposed in its 2018 Integrated Resource Plan to build two 6MW turbines for research, and surveyed the 27-mile route of the 34.5kV AC submarine distribution cable from those turbines to the planned connection with the grid near Camp Pendleton. In 2019, the utility announced plans to build the entire wind farm.17

the 27-mile route of the 34.5kV AC submarine distribution cable

Source: Mid-Atlantic Ocean Data Portal

The value of oil and gas development on the Outer Continental Shelf could be much larger - or could be zero. Hydrocarbons may exist in sediments as much as 7.5 miles thick that have accumulated on the OCS after Pangea broke up and the Atlantic Ocean formed. The crust underneath the OCS near Virginia may be a Grenville-age remnant of the original North American continent (Laurentia), the basement of island arcs that accreted onto the continent as the Iapetus Ocean closed, or a chunk of crust broken off from Africa as the continents split.18

oil and gas may be found in basins (embayments) where sediments accumulated after the breakup of Pangea

Source: North Carolina, Report of the Governor's Scientific Advisory Panel on Offshore Energy (Figure 4-1, Figure 5-2)

Whatever its origin, the crust thinned and tilted down as the Atlantic Ocean widened, providing the platform for accumulating a wedge of sediment that extends from the Fall Line to the Continental Slope. Within that wedge, there are multiple basins and faults, potentially creating hydrocarbons traps large enough to justify the development of an offshore oil/gas field and development onshore of supporting infrastructure.

Wells drilled onshore in the Middle Atlantic states have failed to identify enough oil or gas to justify further development, but offshore potential is still unclear. The 2007-2012 Final Environmental Impact Statement noted:19

continental crust (one billion year old Grenville basement bedrock) lies under sediments which cover the Outer Continental Shelf

Source: National Park Service, Topography of a Passive Continental Margin

After the US Congress failed to extend the moratorium on oil and gas leasing off the Atlantic Coast in 2009, the Obama Administration scheduled the sale of an oil and gas lease (Sale 220) off Virginia as part of the 2007-2012 leasing plan. After making that proposal, a British Petroleum well blowout preventer failed and gas/oil spewed into the Gulf of Mexico. The Department of the Interior then cancelled Sale 220 in 2010.

chemosynthetic bacteria feed on methane seeping from the ocean floor near Norfolk Canyon, providing the foundation for a food chain including Bathymodiolus mussels and spider crabs one mile deep in the ocean

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS) "Science Features" - Life in the Abyss

In preparation for a future lease after canceling Sale 220, the Federal government explored the seafloor of the OCS through the Deepwater Atlantic Canyons project. About 90 miles east of Virginia Beach near Norfolk Canyon, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) documented 17 methane seeps, places where hydrocarbons trapped underneath sediments on the OCS escape to the surface. In contrast to the volcanic "black smoker" plumes that spew hot fluids at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the OCS seeps off the Virginia/Carolina coasts are emitting "cold" methane at the temperature of seawater at the site.20

The plumes of detectable methane rose over 1/2 mile high in the water. Carbon trapped in the seafloor suggests that the seeps have been in existence for over 2 million years. Mats of chemosynthetic benthic communities on the seafloor rely upon the hydrogen sulfide and/or methane venting into the ocean, and do not require sunlight to survive. In addition, various species of cold-water corals were discovered on the walls of the deepwater canyons cutting into the eastern edge of the continental shelf.21

multiple canyons on the edge of the Outer Continental Shelf show where rivers flowed 18,000 years ago

Source: Mid-Atlantic Regional Council on the Ocean (MARCO), Mid-Atlantic Ocean Data Portal

Any development of the hydrocarbon resources and mining minerals on the OCS will be regulated by the Federal government. Federal laws will require mitigation of environmental impacts wherever the seafloor is disturbed, and allocate royalties from offshore oil and gas or mineral leases.

Source: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), Submerged Paleocultural Landscapes Project

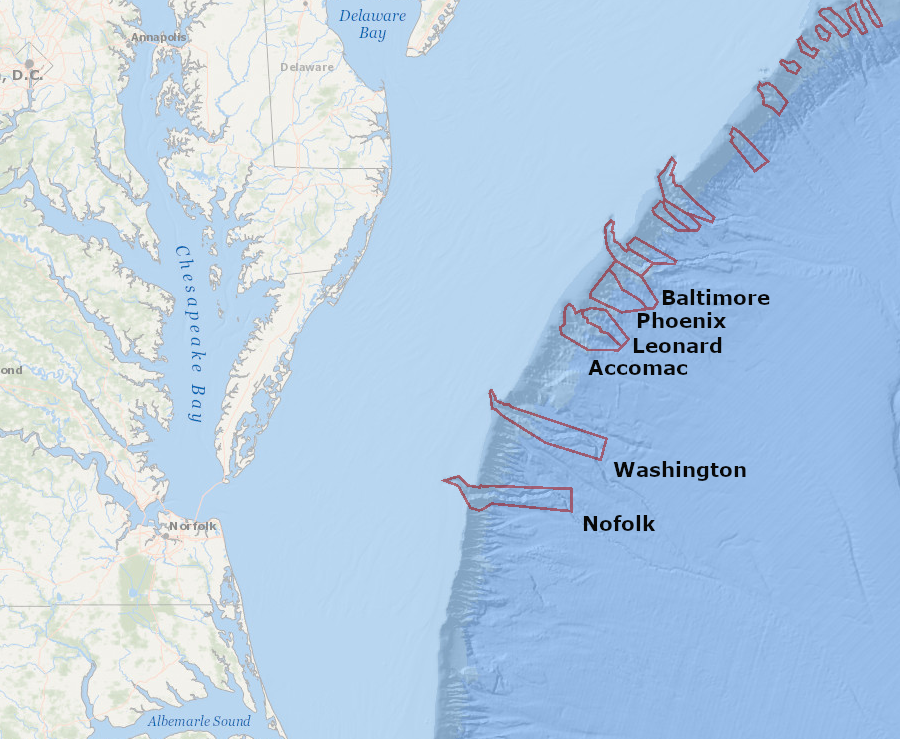

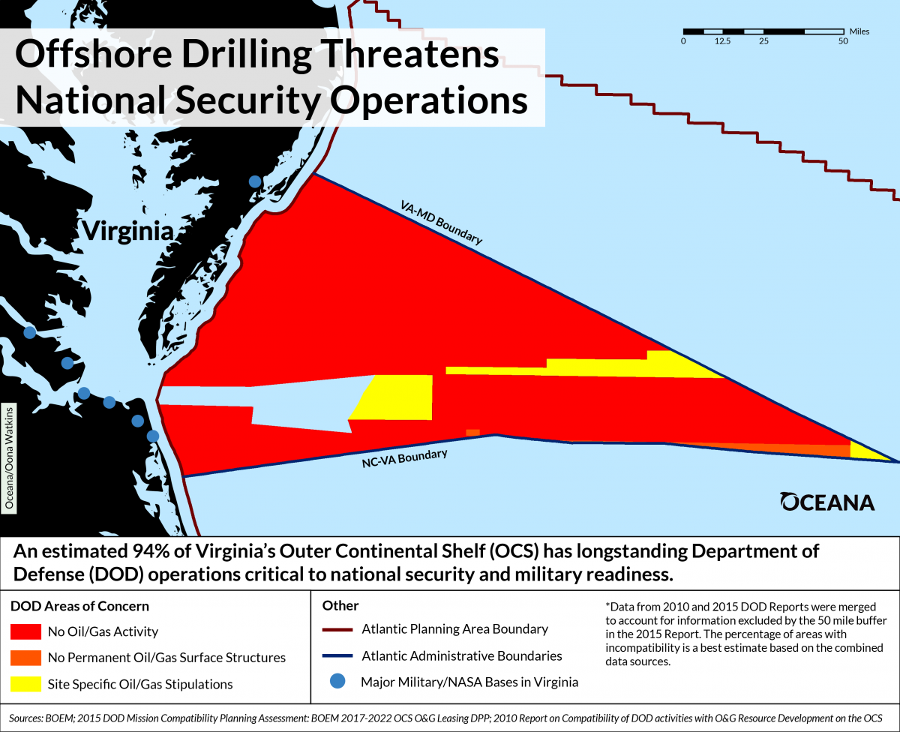

Military considerations could severely constrain where hydrocarbons could be developed off the Virginia coastline. In 2017, Oceana (the main US advocacy group for protecting oceans) reported that 94% of the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Virginia was required by the Department of Defense for air and naval military training. Oil and gas drilling platforms and pipelines would interfere with operations of ships, submarines, and aircraft, including antiballistic missile defense training conducted from Wallops Island.22

Oceana reported in 2017 that Department of Defense activities are incompatible with offshore drilling infrastructure for much of the Atlantic Ocean off Virginia

Source: Oceana, Maps Highlight Department of Defense Conflicts with Potential Offshore Drilling Activities in Atlantic Ocean

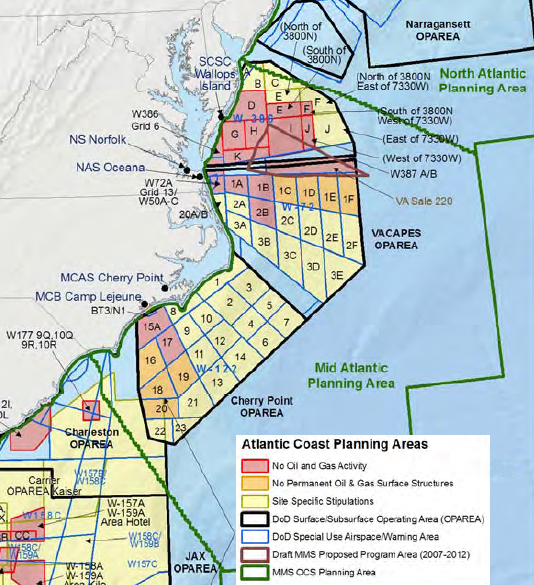

The Department of Defense has commented upon proposed Atlantic Ocean leases, mapping areas on the OCS according to four categories of objection/acceptance:23

Department of Defense comments on suitability for leasing OCS tracts vs. military operation concerns

Source: Department of Defense - Report on the compatibility of Department of Defense (DoD) activities with oil and gas resource development on the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) (2010)

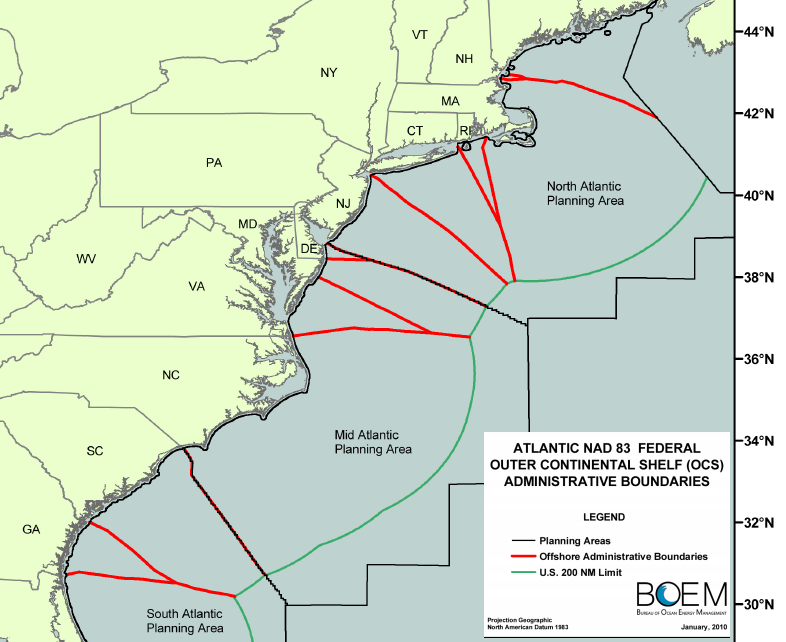

If Congress ever passed legislation requiring the Federal government to share revenues from OCS hydrocarbon leases with coastal states - Virginia's two Democratic senators and the Republican Representative from the Second District (including all of Virginia's Atlantic Ocean shoreline) proposed sharing 37.5 percent in 2013 - then Federal administrative boundaries for the OCS would affect how much Virginia receives in royalties.24

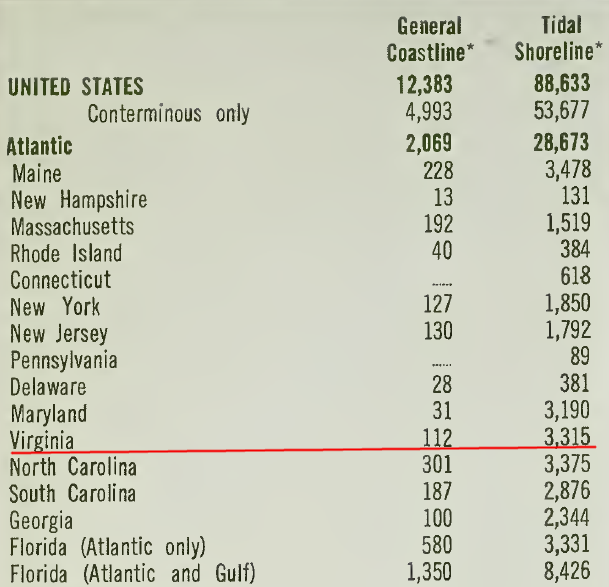

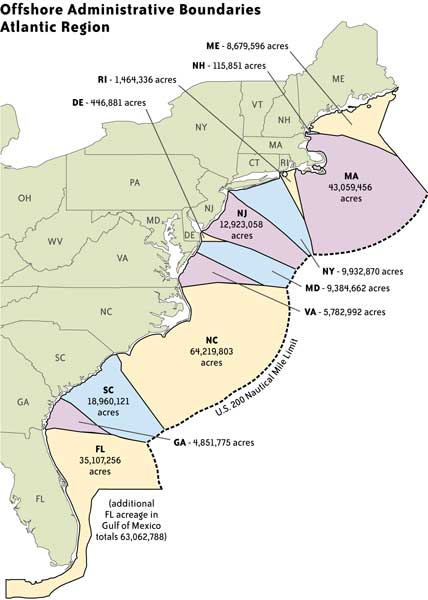

Federal OCS lands assigned to different states, potentially affecting how much in royalties might be provided to each state from oil/gas revenues

Source: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Federal Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Administrative Boundaries

The 2013 legislative proposal would have modified the way the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) in the Department of the Interior has projected administrative boundaries into the Atlantic Ocean. In 2006, a predecessor to the BOEM defined Administrative Boundaries extending from the Submerged Lands Act Boundary seaward to the Limit of the United States Outer Continental Shelf. The projected boundaries define planning areas, and the portion of each planning area allocated to coastal states.

The projection of administrative boundaries was based on the National Baseline, extending eastward from the mean lower low water (MLLW) mark. The lines were not extended in a straight line from the state boundaries on the coastline. Instead, the Federal agency used the principle of equidistance, so every point on the line is equidistant from the nearest points on the baseline. As a result, Virginia's share of the planning area pinched out in a narrow triangle.25

The senators proposed the Federal agency must revise the map of the Mid-Atlantic planning area, so each state's share of the leasable area would be directly proportional to its length of the "Tidal Shoreline" of the Mid-Atlantic States.

Tidal Shoreline includes the Chesapeake Bay, while General Coastline measures just the mileage along the Atlantic Ocean

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), The coastline of the United States (1975)

Revising the boundaries lines for OCS planning areas to reflect the percentage of Tidal Shoreline would reduce the portion of the planning area assigned to other states, and expand the portion assigned to Virginia. Expanded acreage assigned to Virginia would expand Virginia's share of revenues from offshore oil and gas leases - assuming commercial levels of hydrocarbons are developed, and assuming Congress determined that revenues from Atlantic Ocean leases would be shared with coastal states.

By using "Tidal Shoreline" (including Chesapeake Bay shoreline) as the metric rather than the principal of equidistance, Virginia's share of the 80-million acre Mid-Atlantic Planning Area would increase from 7% to 32%. If "General Coastline" mileage had been used rather than "Tidal Shoreline," Virginia's share would increase to 24%. Either way, Virginia would receive more income from offshore leases - if the Federal government chose to share revenues with states for oil and gas leases in the Atlantic Ocean.26

The original 2014 draft of the 2017-2022 Five-Year Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Oil and Gas Leasing Program included the waters off the southeastern United States, adding some urgency to the debate over Virginia's appropriate share of revenues from offshore Federal oil and gas leases. The Proposed Program unveiled in March, 2016 dropped plans for a sale in that region, and proposed sales only in the Gulf of Mexico and near Alaska.

The Atlantic Ocean sales were dropped in part due to objections by the US Navy (concerned about any new constraints on its area for training) and NASA (concerned about restrictions on satellite launches from the Wallops Flight Facility).

Sale 220 was cancelled after the BP well blowout in Gulf of Mexico in 2010

Source: Department of the Interior, Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Strategy

Another factor influencing the Obama Administration's decision to drop Atlantic Ocean sales was the opposition of some local governments, including both Accomack and Northampton counties on the Eastern Shore. Those local governments chose to focus on economic development based on tourism, and joined with environmental advocates to oppose drilling. Offshore oil development might create some local jobs and revenues, but an oil spill could cause create the impression in the minds of potential tourists that the Virginia shoreline had been "ruined."

The Lieutenant Governor, who came from Northampton County on the Eastern Shore, broke with his fellow Democrat Gov. Terry McAuliffe to oppose any lease sale.27

State officials remained committed to the "all of the above" strategy for energy development. The votes of Virginia's two US Senators reflected changing circumstances on how the state would benefit from offshore oil and gas development.

At the end of 2016, after the Federal government had omitted waters off Virginia from the 2017-22 offshore drilling plan, the US Senate blocked a bill that would have increased the share of oil and gas royalties distributed to coastal states from Federal leases. Both Virginia senators had supported the bill when leasing off Virginia might have led to increased state revenues, but they opposed the bill once Atlantic Ocean leases were dropped.28

Under President Trump, the Department of the Interior proposed a 2019-24 Outer Continental Shelf leasing program that reversed course, and once again included Federal waters off Virginia. The Trump Administration also proposed ending the program through which states received a share of oil and gas leasing revenue from Federal oil and gas leases on the Outer Continental Shelf.

In response, Gov. McAuliffe altered his "all of the above" strategy and objected to potential leasing. The governors of North Carolina and South Carolina did similar switches. Gov. McAuliffe notified the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management:29

The request was not heeded. At the end of 2018, the National Marine Fisheries Service authorized seismic testing, allowing sound guns to issue acoustic signals to assess sedimentary formations on the Outer Continental Shelf. The results would update seismic data that was three decades old. The "incidental harassment authorization" was needed because sounds could deafen dolphins and the endangered North Atlantic right whale, whose population had dropped to just 100 breeding females.

The controversial decision came right after the United States Global Change Research Program issued Volume II of the Fourth National Climate Assessment. That report highlighted expected impacts from rising temperatures and sea levels.

No seismic testing occurred. Lawsuits delayed testing for locating oil/gas deposits for drilling, until the permits expired in 2020. Similarly, no new oil and gas leases were issued by the Trump Administration. The president placed a moratorium on his own plan during the 2020 election campaign, in particular to gain support in the key states of Florida and North Carolina.

In 2020, however, Governor Northam signed legislation passed by the General Assembly banning oil and gas drilling in Virginia waters. The law provided clear direction to the Virginia Marine Resources Commission, which manages the state-owned submerged lands:30

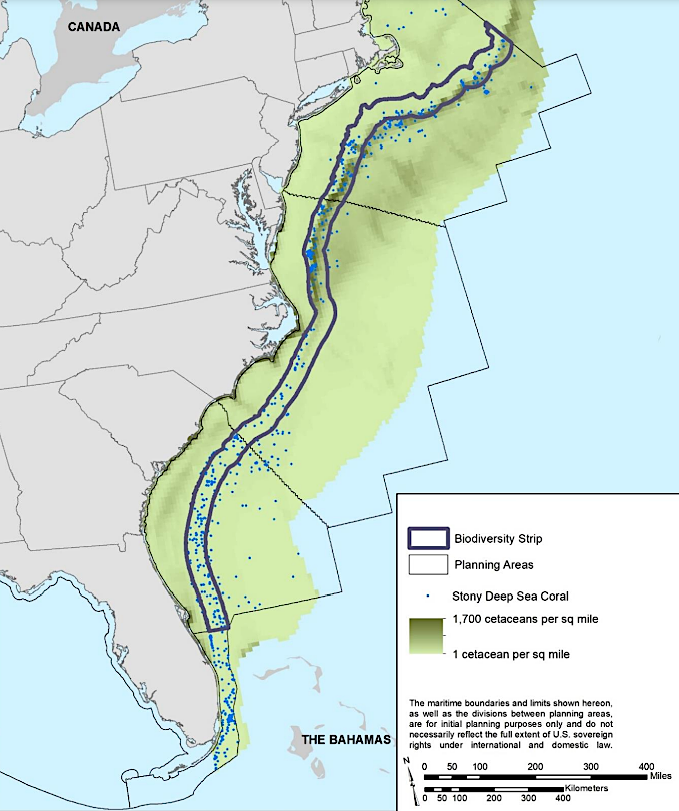

In 2022, the Biden administration issued its 2023-2028 National Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing Program, as required under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act. That five-year plan banned any drilling for hydrocarbons with Federal waters of the Atlantic Ocean. At the time, Russia's invasion of Ukraine has disrupted the energy markets and caused a spike in prices.

Virginia has 5.8 million acres in the Mid-Atlantic Planning Area, but in 2016 the Department of the Interior stopped planning for any offshore Federal oil and gas lease there

Source: American Birding Association, Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement for 2023-2028 National OCS Oil and Gas Leasing Proposed Program (Figure 4-21)

the Biden Administration identified where biodiversity was concentrated in offshore canyons and whales were concentrated in a biodiversity strip at the edge of the Continental Shelf

Source: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), Draft Programmatic Impact Statement, 2023-2028 National OCS Oil and Gas Leasing Proposed Program (Figure 4-19, 4-21)

Despite concerns about global warming, President Biden was sensitive to the political impacts of the high prices at American gas stations at the time his plan was released. The leasing program proposed to continue drilling in the Gulf of Mexico and Cook Inlet, Alaska. At the end of his administration in January, 2025, President Biden used a provision in the 1953 the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act to withdraw lands from leasing and block offshore drilling on 625 million acres of the Outer Continental Shelf. All potential leases in Federal waters off the Virginia coastline were included in that withdrawal.

oil and gas leases were banned in January, 2025 in Federal waters off Virginia's coastline

Source: US Department of the Interior, Pacific Gulf Atlantic Withdrawal (January 6, 2025)

On February 3, 2025, his first day as the new Secretary of the Interior appointed by President Trump, Doug Burgum signed Secretary's Order 3420 revoking the withdrawal. Interior staff were directed to plan new leases. By the end of October however, there had been sufficient political resistance that new leases in the Atlantic Ocean were dropped from the draft offshore drilling plan.31

During Biden's four years in office, Federal officials approved 11 commercial-scale offshore wind projects on the Outer Continental Shelf. President Trump considered wind turbines to be "garbage in a field." As he prepared to assume office for the second time in 2025, he said:32

In addition to providing energy resources, offshore sediments on the Outer Continental Shelf may be mined for heavy metals such as titanium. A high percentages of ilmenite, a titanium-rich mineral, has been found in Coastal Plain sediments and in samples dredged from the shelf off the coast of Virginia. The original source for the titanium is the igneous and metamorphic crystalline bedrock of the Blue Ridge and Piedmont.

Through erosion, particles of sediment were carried by rivers to the shoreline, where wave action concentrated the heavy titanium particles on the beach. The Old Hickory placer deposit in Sussex and Dinwiddie counties, mined by Iluka Resources since 1997, marks the location of an ancient beach when sea level was higher. Offshore placer deposits near Hog Island, Smith Island, Virginia Beach, and False Cape indicate where titanium-rich sands were concentrated when sea level was lower, or by ocean currents in the last 18,000 years after sea level began to rise again.33

"cold" methane seeps, emerging at the temperature of the seawater one mile deep, are located off the New Jersey and Virginia coasts

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), NOAA explorers discover deepwater gas seeps off U.S. Atlantic coast (December 19, 2012)

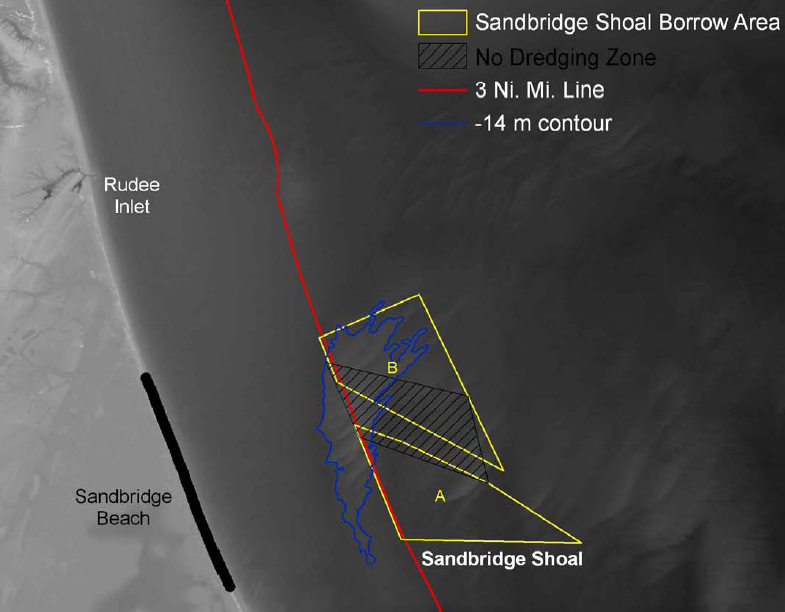

For the moment, however, the most valuable offshore mineral resource being utilized is sand, simple sand. Beach replenishment projects for Virginia Beach (including Sandbridge) rely upon Federal offshore sand, mined from locations beyond the 3-mile boundary.34

mining sand within Sandbridge Shoal lease area, outside the 3 nautical mile limit, is authorized by a Federal agency

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Draft Environmental Assessment, Sandbridge Beach Erosion Control, And Hurricane Protection Project, Virginia Beach, Virginia

The US Army Corps of Engineers dredges sediments from the Atlantic Ocean Channel to maintain a 52-foot deep shipping channel for coal carriers, container ships, and the US Navy aircraft carriers moving through Hampton Roads. The dredge "spoils" from the Atlantic Ocean Channel are 85% sand and only 15% silt.35

The sand-rich material is recycled for use in beach restoration projects at Virginia Beach, as is the sand removed from the Rudee Inlet channel. Both the Atlantic Ocean Channel and Rudee Inlet are within the three-mile limit under state authority.

State approval for the removal of underwater resources in the channels is provided through agreements with the US Army Corps of Engineers for dredging operations, and the local ports and local tourism economy are the primary beneficiaries of beneficial reuse of sediments with a grain size of greater than 0.2mm. The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) evaluates the water quality impacts of dredging the channels, and issues Virginia Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (VPDES) permits to the US Army Corps of Engineers for that activity.36

after dredging Rudee Inlet, the Corps of Engineers deposits sand 500 feet from shore so it replenishes the beach

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, USACE vessel Currituck dredges Rudee Inlet

sand pumped onshore from a dredge via pipeline is spread by bulldozer to reshape Virginia Beach

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers,

Virginia Beach Hurricane Protection Beach Renourishment Project

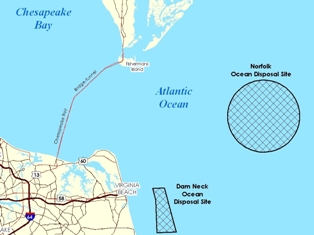

The US Army Corps of Engineers regularly removes sediments from the Hampton Roads shipping channels. It transports much of the dredge spoils from the Thimble Shoals channel and Atlantic Ocean Channel to the Dam Neck Ocean Disposal Site (DNODS) and the Norfolk Ocean Dredged Material Disposal Site, for disposal on the Federally-managed portion of the Outer Continental Shelf. Under the 1972 Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act (MPRSA), the Corps is responsible for permitting ocean disposal of dredged materials even within the three-mile limit.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has authority to approve permits for deposition of other materials in the ocean, including burial at sea of human remains and disposal of retired vessels. The U.S. Coast Guard has responsibility for surveillance of ocean dumping, which may occur as ships enter territorial waters and pump their bilges. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) conducts long-range research to identify how the marine environment is changing, including impacts of materials disposed on the Outer Continental Shelf.

EPA designates the authorized ocean disposal sites for all types of materials, including the materials deposited under US Army Corps of Engineers permits. To ensure consistency, the Corps uses EPA's environmental criteria when evaluating proposals to dump dredge spoils in the ocean.37

disposal sites on Outer Continental Shelf off Virginias coast, permitted by EPA

Source: Environmental Protection Agency, Mid-Atlantic Permitted Ocean Disposal Sites

The High Seas Treaty went into effect in 2025, establishing international law beyond the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The United States signed the treaty during the Biden Administration. The second Trump Administration was not expected to adhere to it. President Trump ignored the Law of the Sea when he directed the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to issue permits for deep sea mining. Such mining was, according to the treaty, to be permitted only after the International Seabed Authority had issued regulations.38

east of the Outer Continental Shelf lies the Abyssal Plain and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

Source: Library of Congress, Manuscript painting of Heezen-Tharp "World ocean floor" map by Berann

U.S. Continental Shelf Boundary areas (limit of U.S. jurisdiction for offshore mineral development) do not extend 200 miles off the southeast coast of Florida

Source: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, CSB Bathy Map

Gov. McAuliffe made clear in 2017 that state support for oil and gas leases on the Outer Continental Shelf depended upon the potential for Virginia to receive revenue from those leases

Source: Newsroom, Governor of Virginia (August 11 2017)