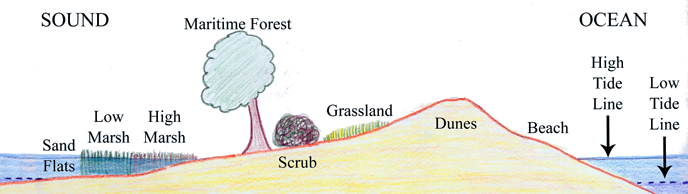

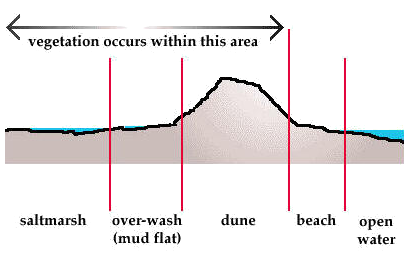

Barrier islands are typically thin strips of sandy beaches on the ocean side, with a line of sand dunes in the middle and a salt-water marsh between the dunes and a lagoon/bay. A maritime forest may grow behind the dunes if the island is wide enough.

profile of a typical barrier island

Source: National Park Service, Cape Lookout Geologic Activity

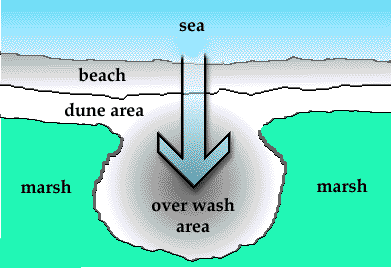

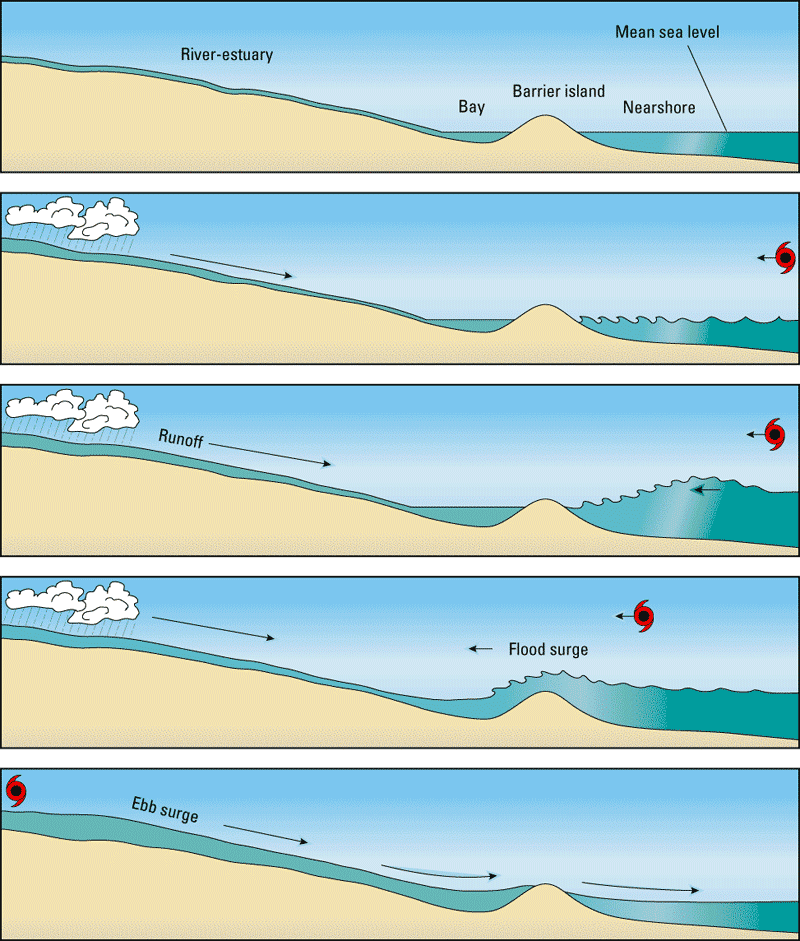

Barrier islands are constantly re-shaped by storms. Overwash fans develop when waves breach the dunes, carrying sand inland and depositing it at flood tide behind the dunes - sometimes covering the maritime forest or marsh with a layer of fresh sand, but often filling some of the open water in the bay/lagoon. Barrier islands are widened by such flood-tide deposits, especially after saltmarsh cordgrass (Spartina patens) extends into the new deposit and starts growing to expand the marsh, but currents and storms can simultaneously narrow barrier islands by eroding sand from the ocean side.

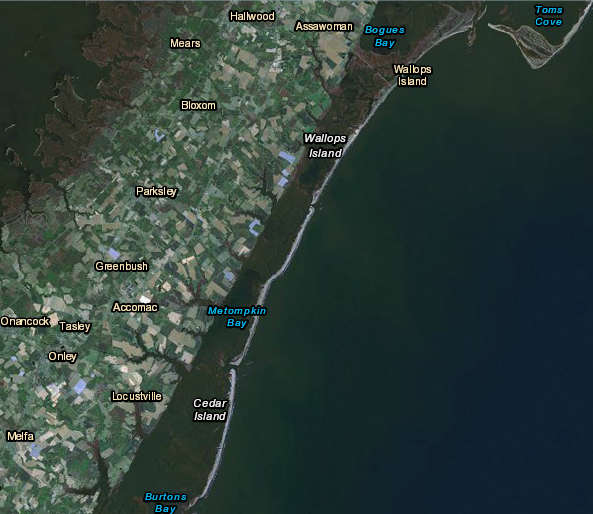

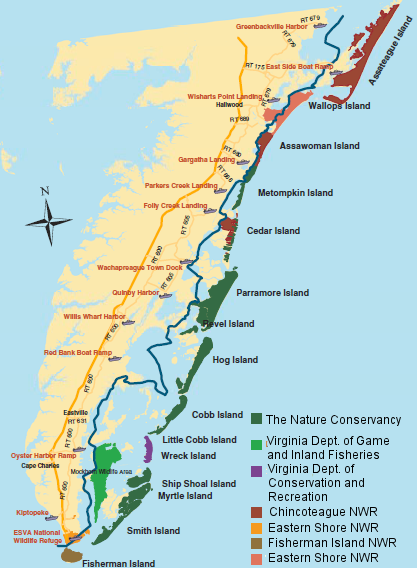

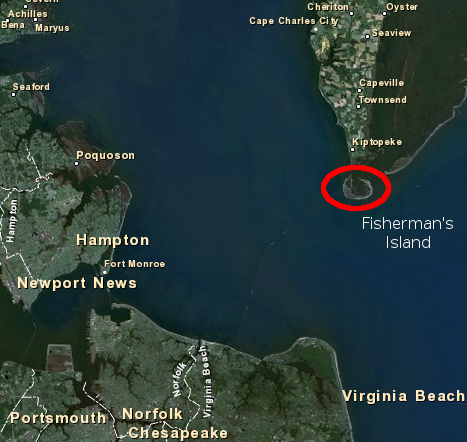

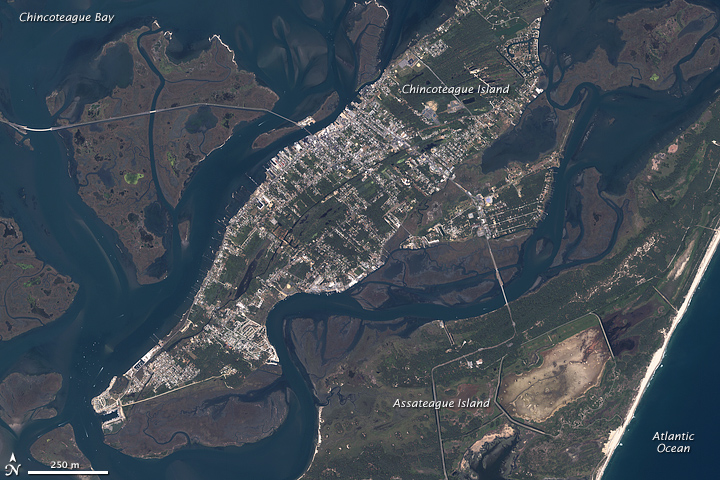

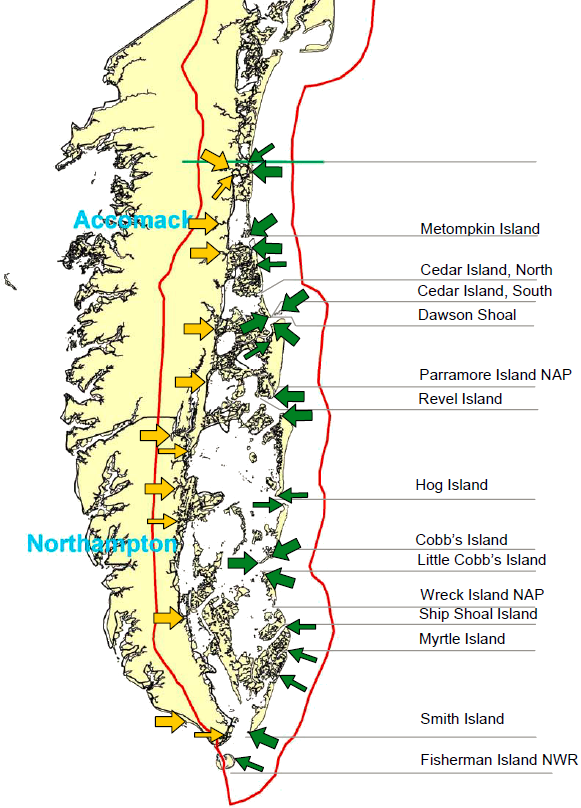

on Virginia's Eastern Shore, barrier islands extend from Assateague Island (with Tom's Cove on southern tip) to Fisherman's Island - and south of the Chesapeake Bay, additional islands extend to the North Carolina line at False Cape State Park

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Earth Observatory, Fall Colors in the Mid-Atlantic

If a storm surge raises the height of water in the bay, a flood in the other direction may burst through the dune line and create an ebb-tide sand bar on the ocean side of the island. Such sand bars are quickly eroded by wave action, with sand carried south on the Virginia coast by longshore currents. Southern tips of Assateague Island and Hog Island are growing today, while the northern tips are eroding away.

it is normal for hurricanes to open new inlets cutting across barrier islands

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Photos before and after Hurricane Sandy opened a breach on Fire Island

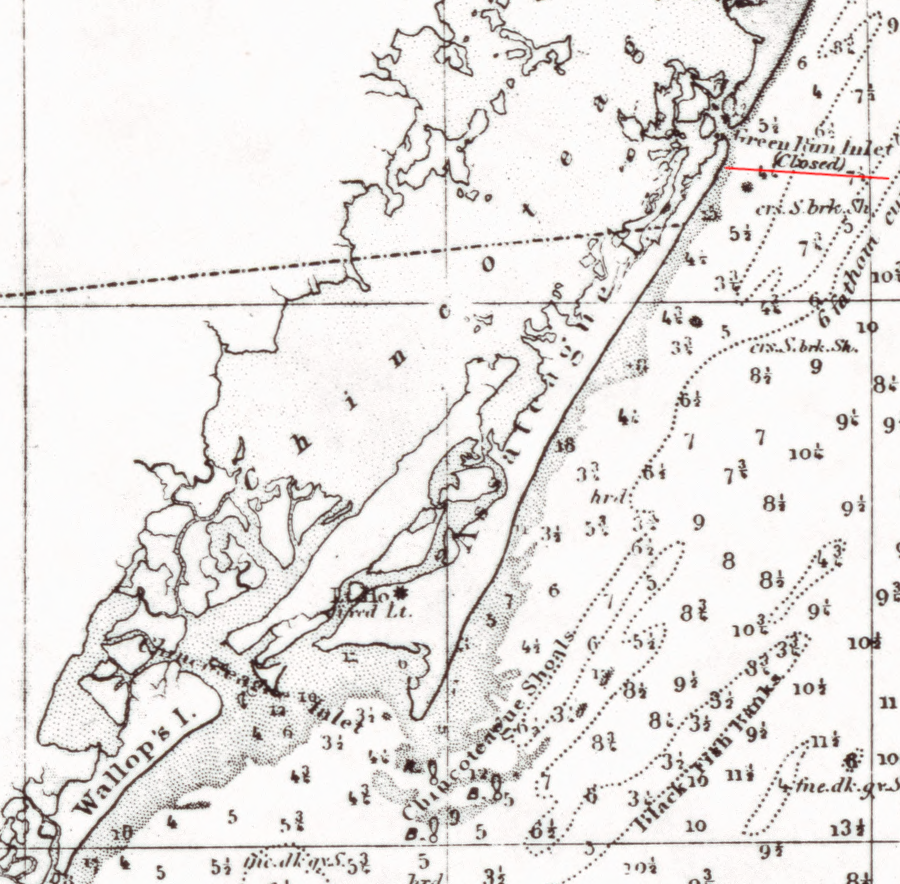

The shifting landscape of barrier islands is not a recent discovery. The Green Run Inlet that divided Assateague Island and linked Sinepuxent Bay with the Atlantic Ocean was open only about 30 years in the mid-1800's. It was not until 1933 that a new inlet opened. Over a century ago, one writer commenting about the earlier settlement history of Hog Island noted:1

natural processes opened and closed Green Run Inlet on Assateague Island after about 30 years

Source: Library of Congress, General chart of Delaware and Chesapeake Bays and the seacoast from Cape May to Cape Henry (1882)

Barrier islands are a constantly changing deposit of sand that forms parallel to the coast." Six characteristics distinguish barrier islands as a unique landform:2

barrier islands have a sand beach facing the water, with a lagoon/marsh on the inland side

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Metompkin Inlet 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (2019)

There are over 2,000 barrier islands worldwide, and roughly 400 barrier islands along the coastline of the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico.3

The Delorme Atlas and Gazetteer for Virginia names about 20 major barrier islands on the Virginia coast, with a chain of sandy strips backed by marshes from Assateague to Fisherman's Island on the Atlantic Ocean side of the Eastern Shore. South of the Chesapeake Bay, the barrier islands are welded to the mainland from Cape Henry to Sandbridge, and are not actively migrating for the moment.

barrier islands in Chincoteague Bight - Wallops, Assawoman, Metompkin, and Cedar islands

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

At Back Bay, a new chain of active barrier islands starts, extending south to include Nags Head and the Outer Banks in North Carolina. At False Cape State Park, on the southeastern tip of Virginia, the now-abandoned community of Wash Woods indicates clearly how flood tides and storm surges can bring sand from the ocean side to the bay side of a barrier island.

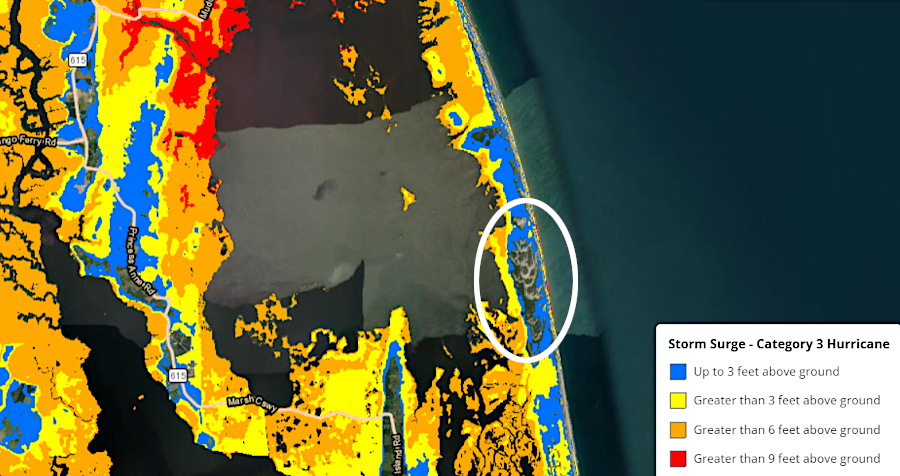

in the storm surge from a Class 3 hurricane, a small part of False Cape State Park would remain above water

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Coastal County Snapshots

Worldwide, there are perhaps 15,000 additional "fetch-limited" barrier islands in low energy settings, sheltered from strong wave action because the distance of open water (fetch) near the island is narrow - less than 20 miles, compared to the thousands of miles on the Atlantic Ocean side of the Eastern Shore. Fetch-limited barrier islands such as Gwynn Island and Plum Tree Island are common in the Chesapeake Bay, where they are protected from the strong swell of ocean waves by the Eastern Shore. Thin sandy beaches protect marshes from wave action, or the marshes themselves fringe the island. Dunes are rare, and the pattern of storms shapes the barrier islands in the Chesapeake Bay:4

the ocean-facing side of the northern tip of Mockhorn Island is protected against wave action by other barrier islands, creating a fetch-limited barrier island landform

Source: US Geological Survey 7.5 minute topographic map, Cobb Island

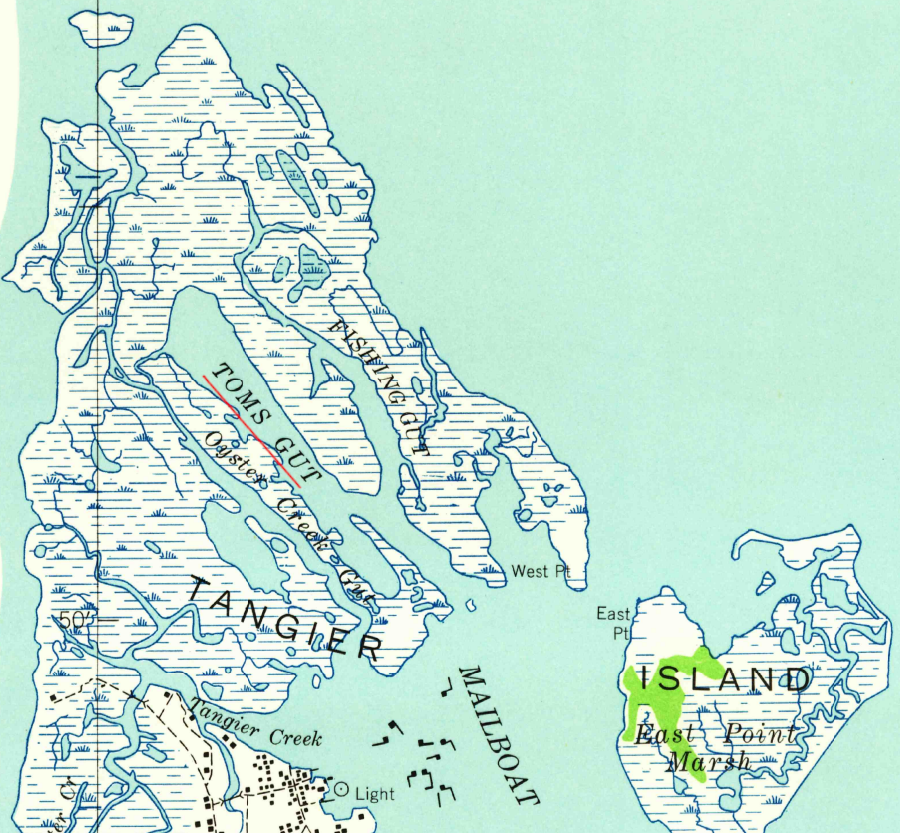

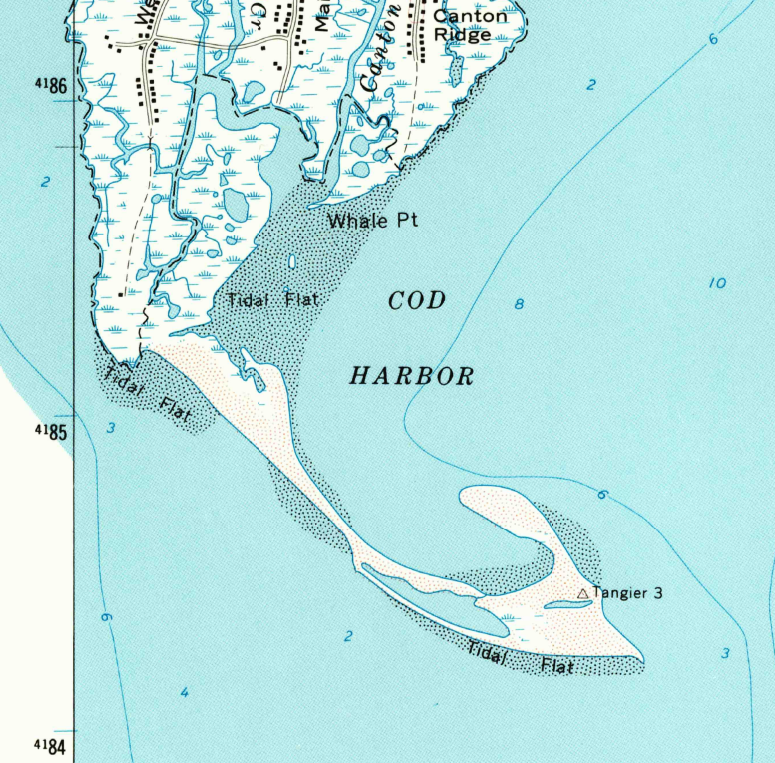

In some cases, such as Tangier Island (balanced on the buried watershed divide of the Nanticoke and Choptank Rivers), wind blows across the Chesapeake Bay with equal fetch in two directions. The waves have created east- and west-facing barrier systems with lagoons and rapidly-changing ebb/flood tide deltas. Such islands are typically sand starved, and likely to disappear into underwater shoals once their saltmarsh anchors are drowned by rising seas.

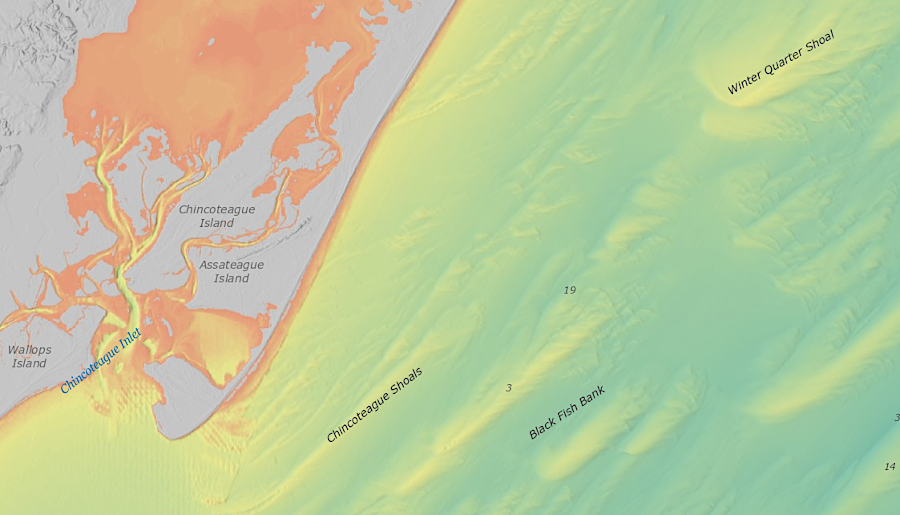

Current barrier islands are only about 6,000 years old, but Virginia's first barrier islands may have formed as much as 200 million years ago after the Atlantic Ocean opened and sediments were deposited on the coastline. The source of the sand particles on modern barrier islands is ultimately the Appalachian Mountains and even Canada.

When rocks erode from the mountains, many minerals dissolved completely, but the chemical bonds of quartz - silicon dioxide, SiO2 - are highly resistant. Quartz remains a solid rock, but is crushed into small grains as rocks wash off the mountains and are carried downstream by rivers. Sand, clay, and gravel particles that survive the transport process from the mountains have been deposited at the shoreline, shifted by currents and waves, re-arranged by rivers when sea level dropped and exposed the Coastal Plain, then moved one final time as sea levels rose when the last Ice Age ended.

Erosion and currents/wave action have created many versions of the coastal shoreline, prior to the modern Delmarva Peninsula. Rivers carry sediment downstream to the ocean. At barrier islands and on eroding edges of rivers, the particles are still moving. Barrier islands are dynamic, with sediment shifting in response to changes in sea level and currents. What appears to be "erosion" as sea level rises is mobilization of sand, silt and clay particles as they "retreat" towards the coastline.

In the mountains, erosion move particles far downstream. They disappear from the local setting, and the height of the mountains is gradually lowered. At barrier islands, wave action moves particles just a few feet back and forth. Island morphology changes as the sediment shifts back and forth, and some particles move north and south along the coastline of Virginia due to currents, but very little sediment is carried eastward towards the edge of the continental shelf. When sea level drops again, the sandy remnants of the Appalachian Mountains that washed downstream to the Continental Shelf will be exposed again as an extension of the Coastal Plain.

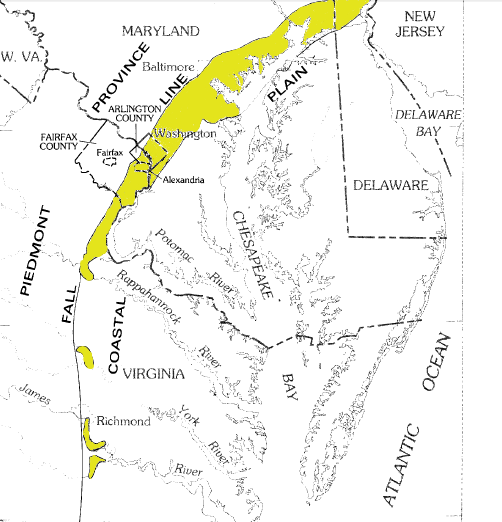

the Potomac Formation is exposed on its western end, but buried deep below the Eastern Shore

Source: US Geological Survey Engineering Geology and Design of Slopes for Cretaceous Potomac Deposits in Fairfax County, Virginia, and Vicinity (Geological Survey Bulletin 1556)

The Coastal Plain was built over the last 145 million years, starting in the Cretaceous Period when the Atlantic Ocean shoreline was roughly where I-95 is located today. Rock particles from the Appalachian Mountains to the west washed down and settled as marine deposits.

The lowest sedimentary layer of the Coastal Plain is called the Potomac Group. It lies on top of the "basement complex" of crystalline rock that dates back to the formation of Pangea or its predecessor supercontinent, Rodinia. The Potomac Group is exposed at the surface on its western edge in Alexandria, but is at the bottom of over 6,000 feet of sediments underneath Accomack/Northampton counties on the Eastern Shore. The youngest sediments at the surface now form the barrier islands.5

aquifers beneath the Coastal Plain are located in sedimentary formations that are up to 145 million years old

Source: US Geological Survey A Surficial Hydrogeologic Framework for the

Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain (Figure 2)

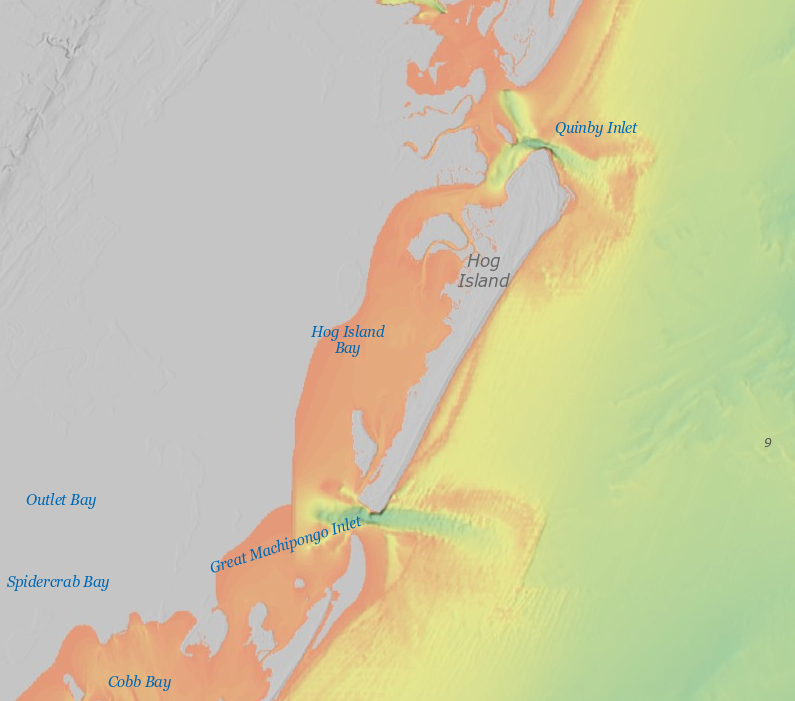

Stingaree Point is growing as longshore currents carry sand south, but currents in Quinby Inlet keep a channel clear - for the moment - between Parramore Island and Hog Island

Source: US Geological Survey 7.5 minute topographic map, Quinby Inlet

heavy, dense grains of hornblend/magnetite/rutile resist movement by wind while dry grains of quartz migrate easier, forming lineaments of dark and light sand on Assateague Island

In the last 10 million years, glaciers scraped across New York state and deposited Long Island, and then as the ice retreated glacial meltwater carried massive amounts of sediment downstream to the ocean. The Delaware, Susquehanna, and Potomac rivers carried eroded sand and gravel eastward to form the Delmarva Peninsula. At the end of the Pliocene and throughout the Pleistocene, sea level dropped and Coastal Plain sediments were shifted around in river deltas and outwash plains.

The loose, unconsolidated sediments that form Virginia's barrier islands were carried south by ocean currents from the mouths of the Delaware River and even the Hudson River. Currents along the Atlantic Ocean shoreline moved material south, blocking river/stream exits and creating offshore sandbars.6 barrierislandva.png

Virginia has 11 major barrier islands

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), Barrier Island Dynamics

The sand grains in a modern dune on Virginia's Eastern Shore may once have been bedrock in Pennsylvania, New York, Quebec, or Ontario. Today, little sand washes all the way from the Appalachian Mountains to the Atlantic Ocean.

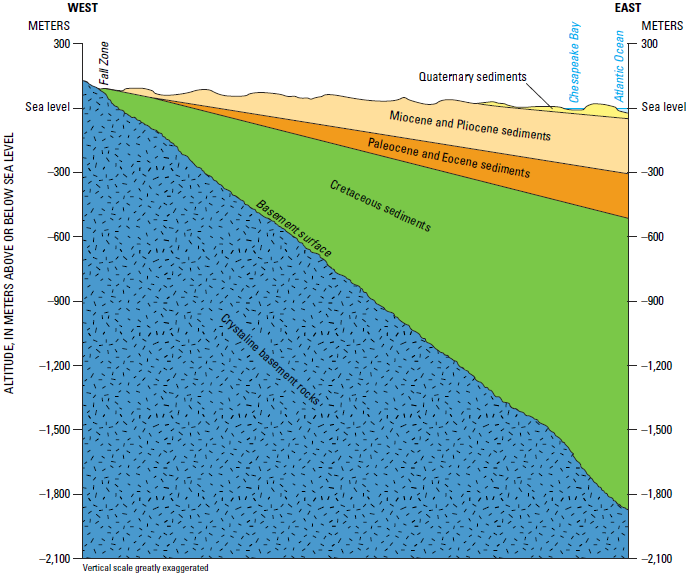

Most large particles eroding off the Blue Ridge today will settle out at the Fall Line, where the rivers reach sea level. Thee are distinct cliffs at Westmoreland State Park and elsewhere on the western side of the Chesapeake Bay where erosion is still recycling Coastal Plain sediments into sandy beaches, but those are west of the Eastern Shore. Most barrier islands are located on the Atlantic Ocean side of the Eastern Shore, rather than on the Chesapeake Bay side.

cliff eroding to recycle sediments

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service

As the sea began flooding over the Continental Shelf at the end of the Ice Age 18,000 years ago, wave action eroded the "headlands" of high ground separating the many creeks that had flowed onto the Continental Shelf. The high ground (watershed divides) was composed of sediments deposited since the Cretaceous Period, reworked in previous retreats and advances of the ocean - so the eroded-and-deposited-and-eroded-and-redeposited sediment particles were mobilized one more time.

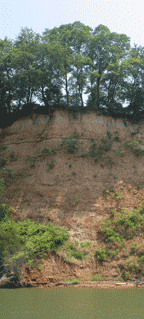

As the Continental Shelf drowned, waves and paleochannel currents shifted the eroded-once-again sediments. Sand and silt particles were sorted and transported; the new bottom of the Atlantic Ocean was covered with offshore shoals. However, the shift in the shoreline, as it migrated from the Continental Slope westward to near its current location, may have been too rapid for development of barrier islands. If sea level rise was greater than 13 inches/century, barrier islands were submerged.

The marshes on the inland (back) side of now-drowned barrier islands were highly productive ecological zones. Underwater archeology may reveal if the sediments of now-submerged barrier islands on the Outer Continental Shelf still retain evidence of early human presence on the coastline. The locations of artifacts may have been disturbed by storm waves and ocean currents; interpretation of dates/settlement patterns from archeological discoveries on submerged barrier islands will always be challenging.

At slower rates, the sand particles are moved inland and barrier islands are re-established in a new location. Once sea level rise slowed down, sand on the Virginia coast could have pushed by wave action into dunes, exposed shoals, and barrier islands shaped by northeasters and other storms.

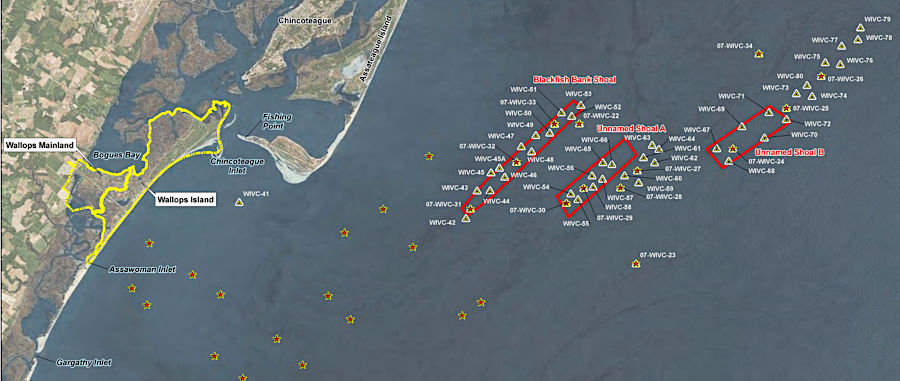

shoals off Chincoteague could supply sand to the barrier island in storms

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Bathymetric Data Viewer

The chain of barrier islands on the coast of North Carolina were in place by 1,500 BC, though hurricanes or a tsunami washed them away around 900 AD and the barrier chain at Hatteras was not reestablished until 1500 AD. Off the Georgia coast, barrier island sediments as old as 40,000 years have been identified at Gray's Reef National Marine Sanctuary. That suggests a barrier island which formed before the Last Glacial Maximum survived as a drowned geomorphic feature during the rise of sea level over the last 20,000 years.7

Off Virginia's Eastern Shore, Assateague Island is a spit formed from sediments eroded from the Delmarva headland to the north, now Cape Henlopen. Erosion from the headland today does not provide sufficient quantities of sand to build barrier islands south of Assateague Island, however.

Barrier islands between Assateague and the southern tip of the Eastern Shore are a tide-dominated system, formed from sediment eroded off local headlands and accumulating on the high points of local drainage divides that have been submerged due to sea level rise. South of Assateague, the tidal channels are where the ancient streams once flowed, while the barrier islands are perched on the old ridges between those streams.8

the storm surge from a Class 1 hurricane would flood Chincoteague and Assateague

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Coastal County Snapshots

"Solid earth" is more mobile than solid, when barrier islands are involved. The National Park Service summarized how sand moves on barrier islands:9

The westward migration of barrier islands on the Virginia coastline is a natural process; each barrier island is constantly being reshaped by ocean currents and storm surges. Oyster shells and tree stumps that once grew on the bay/lagoon side may be exposed and eroded from the ocean side, as the sand of a barrier island migrates. During this marine transgression, shells may be buried in the marsh in an oxygen-free reducing environment and then exposed to oxygen on the ocean side, staining the shells unusually black with deposits of iron pyrite and goethite.

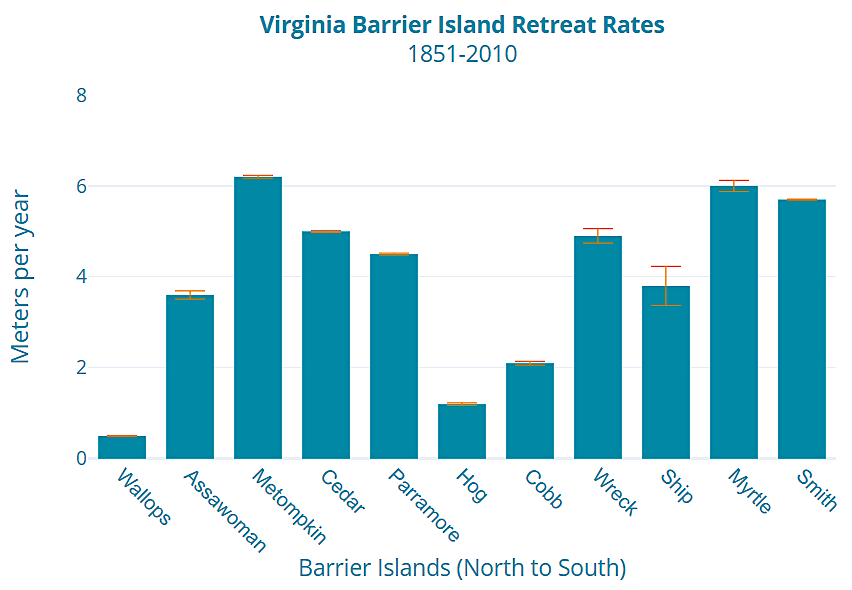

The rate of westward "retreat" varies by island. On average, they move 3-18 feet per year:10

Virginia's barrier islands are moving westward ("retreating") at different rates

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), Barrier Island Dynamics

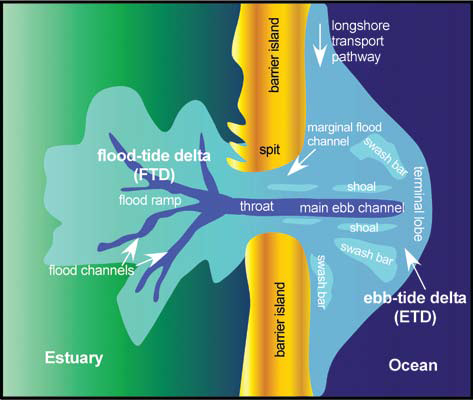

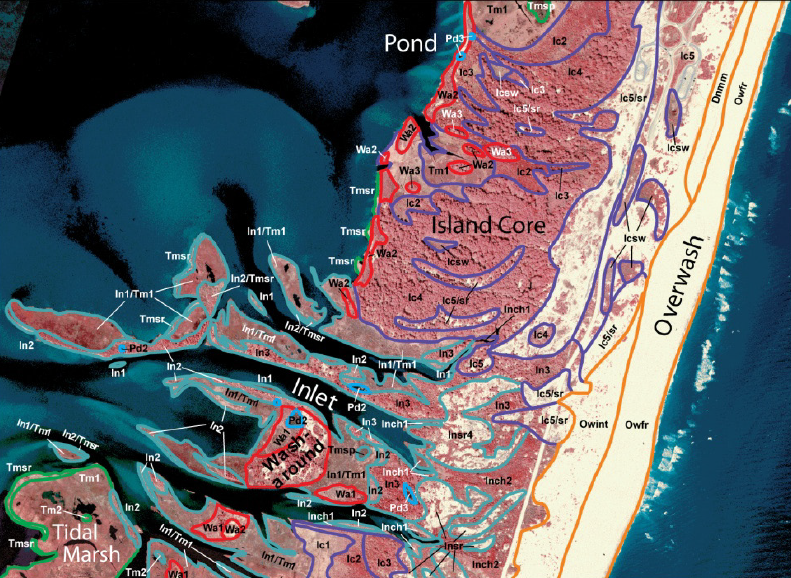

The shape of barrier islands alters as sea level rises. On the Virginia coast, flood tides push sediments westward across low spots. The surging water slows down in the lee of the island. Suspended sand, silt, and clay settles to the bottom, creating a flood tide delta. When wind and waves force water back east across a low spot in the barrier island, ebb tide deltas form. High-energy storms can create surges of sand that overwash an island, burying marshes and forests. Barrier islands have only temporary shapes that morph during storms.

overwash, and deltas formed by flood tides and ebb tides, reshape barrier islands constantly

Source: East Carolina University, Past, Present and Future Inlets of the Outer Banks Barrier Islands, North Carolina (Figure 2)

Building anything on such islands is risky, because the islands are moving. Humans can affect the deposition or erosion of sand by building seawalls or dredging channels, but we can't stop the incessant pressure of the waves as sea level rises and shifts the sand.

Assateague Island

in Maryland, yellow line shows location of single barrier island for Assateague in 1850 - before 1933 storm created Ocean City inlet

(green shaded region shows dramatic westward migration of land south of inlet, in contrast to area north of jetty, by 1942)

Source: Environmental Protection Agency Coastal Sensitivity to Sea-Level Rise: A Focus on the Mid-Atlantic Region (p.51)

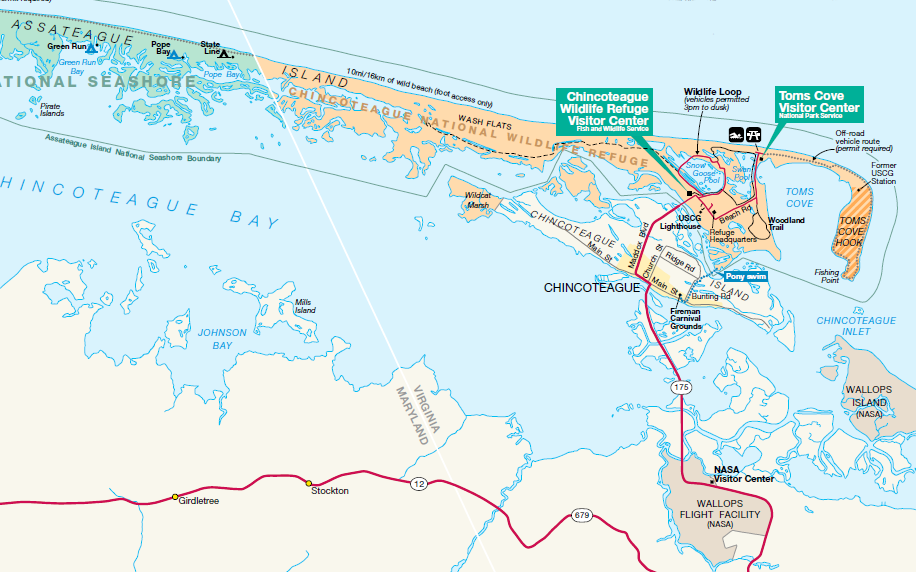

in Virginia, recreation-related development is concentrated on Chincoteague Island and the southern tip of Assateague Island;

NASA has space-related development on Wallops Island and mainland

Source: National Park Service

The natural pattern has a substantial impact on development potential, and on the cost of protecting such development. Sand moves; roads and houses are inflexible. As described by the Department of the Interior in 1979:11

four National Wildlife Refuges (NWR's) managed by the US Fish and Wildlife Service protect a small percentage of barrier islands on the Eastern Shore - most islands are owned by a non-government organization and two state agencies

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, Who Owns Virginia's Barrier Islands?

In the United States, people are moving to barrier islands despite the risks. On barrier islands, population densities are three times the density of the coastal states on average.12

Major development has already occurred on barrier islands in the Town of Chincoteague and the City of Virginia Beach. In addition, the Federal government has developed Wallops Island for launching rockets. The remaining barrier islands on the Atlantic Ocean side of the Eastern Shore are protected in their natural condition by state/Federal agencies and a non-government organization.

The Nature Conservancy acquired its holdings in anticipation of "flipping" the real estate, reselling the islands to a Federal agency for permanent protection. When economics and politics delayed such a sale, the organization invested even more heavily to preserve the shoreline by acquiring farmland and forests on the Eastern Shore. The Volgeneau Virginia Coast Reserve now includes:13

The Nature Conservancy blocked potential resort development projects by obtaining ownership of key spots on the mainland that could have served as ferry ports or the start of a bridge/causeway, then committed to sustainable development of the property to provide employment in local communities and maintain the cultural heritage as well. Stopping the short-term profits associated with new resorts and industrial-scale tourism was not popular in local development or political circles. The owners of Metompkin Island refused to sell it to The Nature Conservancy at any price, seeking instead to boost the economy by selling the island to a development firm call Offshore Islands, Inc. However, the acquisition-savvy conservancy had simply created a dummy corporation, and ended up purchasing the island in disguise.14

Sandbridge, a beachfront home community built on a barrier island near Back Bay Wildlife Refuge, is at risk of washing away. A public policy issue in Virginia Beach is who should pay to replenish the sand to protect private property, an issue that is also a factor for the resort hotel strip further north in Virginia Beach.

Federal subsidies for sand nourishment projects are welcomed by local officials, but taxpayer advocates question the rationale of borrowing funds at the national level to provide highly-localized benefits.

When sand accumulates in the yards of local residents, threatening to cover patios and pools, the homeowners struggle with state requirements to obtain a permit from the Virginia Beach Wetlands Board to move the sand back onto the public beach area. The homeowners do not need any permit to haul the sand away, but replacing it on the beach is not permitted without approval. After the Wetlands Board fined two homeowners who moved sand drifts from their property to the public beach, the Sandbridge community requested an emergency declaration from the City Council to authorize sand transfers.15

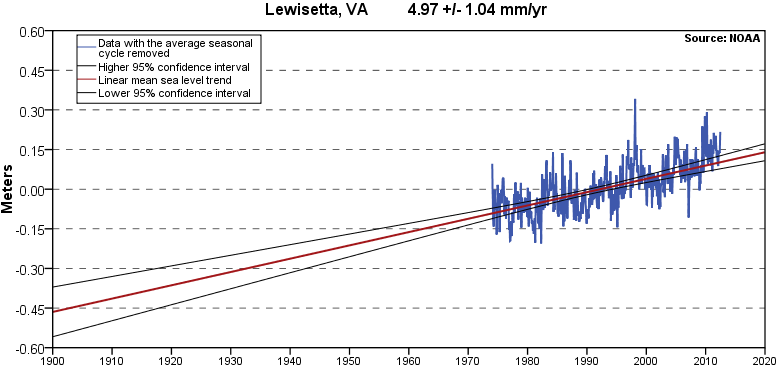

Relative Sea Level rise at Lewisetta, including both Absolute Sea Level rise and land subsidence (while Northumberland County is far from the Chesapeake Bay crater, local faults may trigger subsidence)

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Sea Levels Online, Updated Mean Sea Level Trends - 8635750 Lewisetta, Virginia

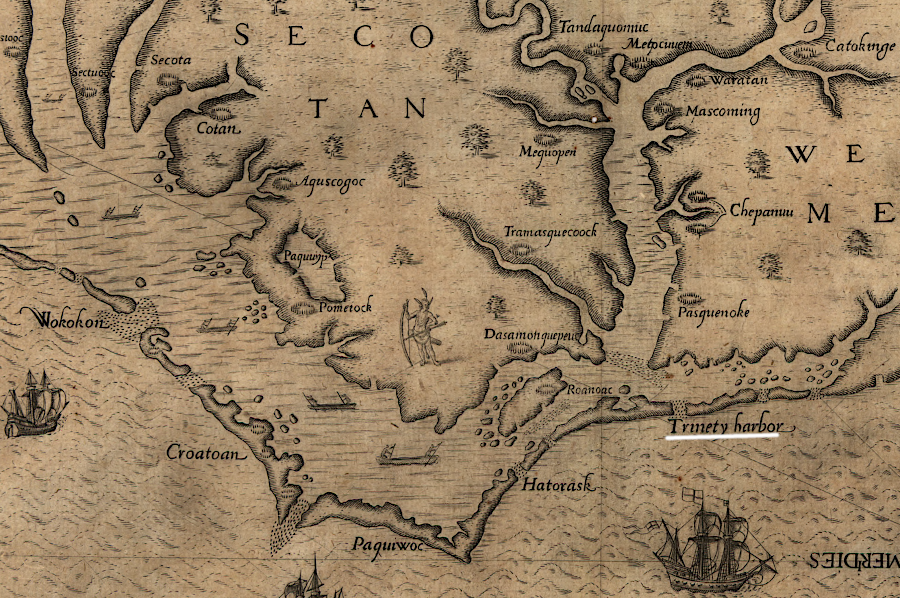

Inlets on barrier islands open during major storms, then silt in and close up over time. In the 1580's, English ships bringing colonists to Roanoke Island encountered a dozen inlets cutting through the barrier islands. Today, between Cape Henry and Ocracoke the only ones remaining are Rudee, Oregon, and Hatteras inlets. The 1580’s were a stormy period when barrier island inlets were being altered.

The closure of Old Roanoke Inlet east of Roanoke Island and the mouth of the Chowan River around 1817 altered currents in Albemarle Sound, causing the main channel from Albemarle Sound to Pamlico Sound to shift from the east to west side of Roanoke Island. That led to erosion of as much as 2,000 feet from the northern end of Roanoke Island, perhaps destroying the site where the "Lost Colony" was established in 1587.

after the Old Roanoke Inlet silted up, currents in Albemarle Sound eroded away the northern tip of Roanoke Island

Source: Library of Congress, Americæ pars, nunc Virginia dicta

There is continuous readjustment ("erosion") now of the sediment that forms the islands of North Carolina's Outer Banks. There are annual news stories highlighting the destruction of houses and infrastructure built near the shoreline on the Atlantic Ocean side of the islands. Those human-built structures are in a fixed location, but the sand particles beneath them are moving westward as sea level rises.

the Outer Banks of North Carolina provide regular news stories about the fate of infrastructure built on migrating sand

Sources: National Park Service, Third house collapses on G A Kohler Court in Rodanthe (September 24, 2024)

By 1985, Orrin Pilkey at Duke University had convinced North Carolina legislators that the geologic processes of shifting barrier islands made it unrealistic to build seawalls in order to "harden" the shoreline. North Carolina has spent a lot of money each year trying to maintain the primary north-south road (NC 12) as the sand continues to move west, but so long as sea level rises the barrier island will shift and the highway's fate is clear.

Pilkey noted in 2021, when the US Army Corps of Engineers was proposing to build a sea wall around downtown Miami that would be 20 feet high in places:16

overwash at high tide is a regular occurence on NC 12

Sources: North Carolina Department of Transportation, NC 12 (Facebook post, September 24, 2024)

In 1933, a hurricane breached Assateague Island, carving an inlet from the ocean to Sinepuxent Bay. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers quickly locked the inlet in place by building a jetty on the north edge, blocking sand transport that would have naturally closed up the inlet. Ocean City then developed as a fishing port and ultimately a beach resort.

cross-section of a barrier island showing vegetation growing on lower-energy side away from wave action, and how storms can push sand past the dune line

Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Barrier Islands - Habitat of the Month; US Geological Survey, The Fragile Fringe

After another storm in 1962, plans for resort-scale development on Assateague Island were dropped and the National Park Service acquired most of the land for a national seashore. That stopped most new residential and commercial construction, but the Federal government agreed to maintain the 1933 inlet. The Ocean City Inlet has been kept open by jetties and by dredging of the channel, and those artificial barriers have blocked sand from drifting southward and renewing the southern part of Assateague Island.

The normal flow of sand, now trapped by the jetty, has created a wide beach on the northern part of the island. South of the inlet, there has been extensive erosion from the barrier island, no longer resupplied with sand by longshore currents. Without natural replenishment, the barrier island just south of the inlet has shrunk and migrated westward substantially.

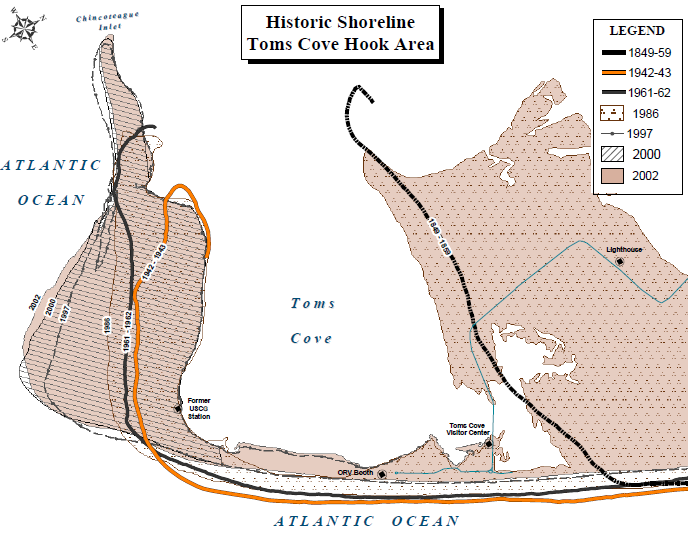

Sand from the longshore currents still flows to Virginia, ending up at Toms Cove near Chincoteague. That portion of Assateague Island is still growing (accreting), extending the southern end of the island and creating a sandbar "hook." Further south, the shoreline veers westward forming the Chincoteague Bight. According to the US Geological Survey, the pattern of changing ocean currents has shaped the shoreline:17

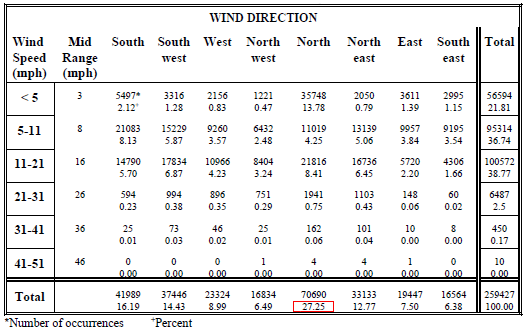

summary wind conditions at Norfolk International Airport from 1960-1990

(winds blow more often, over 27% of the time, from the north - pushing water/sand to the south)

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Chesapeake Bay Shoreline Evolution Reports - Accomack County (Table 1)

Shifting sands require constant repair/reconstruction projects to maintain a paved beach parking lot on the southern portion of Assateague Island that is south of the Maryland-Virginia border. To maintain its tourism-based economy, the Town of Chincoteague has expressed its preference for perpetual Federal maintenance of the bridge from Chincoteague Island to Assateague Island and recreational facilities on Assateague, so people can drive their own vehicles to the ocean shore for fishing, swimming, and sunbathing.18

In 2011, during drafting of the Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP) for Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, the US Fish and Wildlife Service agreed to maintain vehicle access to Assateague Island for the next 15 years - but rejected proposals to build groins/jetties, or to replenish sand through long-term beach nourishment.

Fighting natural shoreline processes at the wildlife refuge is both against Federal policy and too expensive. The CCP proposal continues a long-standing Federal policy at Assateague National Seashore, articulated by a senior Department of the Interior official back in 1975:19

shifting shorelines at Tom's Cove

Source: National Park Service Historic Shorelines of Toms Cove

Any construction on a barrier island is at risk of being eroded away, or shifted inland as the beach expands. The Assateague Island lighthouse in Maryland was built in 1833 next to the ocean shoreline, but today that site is almost two miles inland.20

Along the Eastern Shore, the Virginia islands themselves are so low they are at risk of complete inundation in a northeaster or hurricane. In an 1831 storm, only the high ridges of Smith Island remained above water, providing shelter among the pine trees to cattle and sheep.21

Everything on a barrier island is subject to change. Overwash during storms is a normal process, absorbing the storm energy and redistributing the sand inland. Tree stumps from forests that once grew on the bay side of barrier islands are occasionally exposed on the ocean side, showing the migration of the beaches to the west after years of big storms.

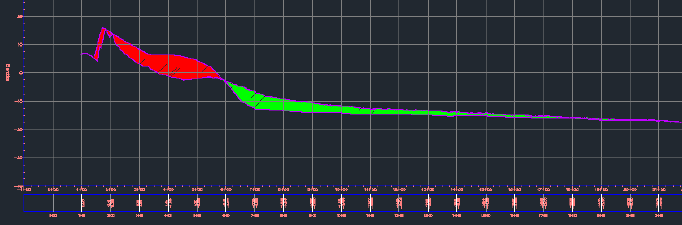

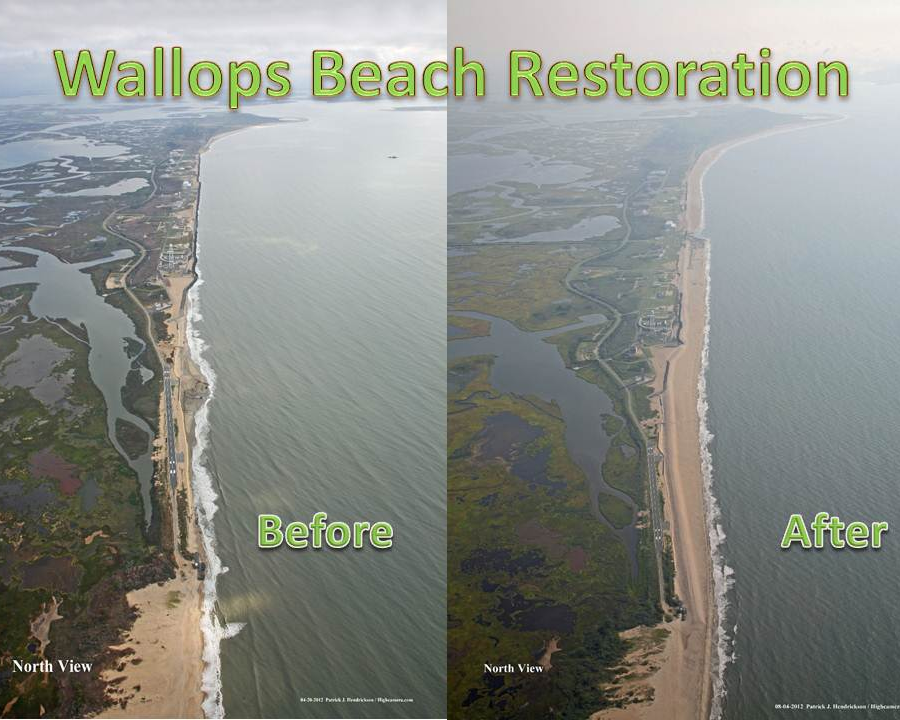

cross section showing Hurricane Sandy-induced shoreline change in 2012 at Pad 0-A (red shading indicates erosion; green shading indicates deposition)

Source: Final Environmental Assessment, Wallops Island Post-Hurricane Sandy Shoreline Repair (June 2013, p.1-7)

On Hog Island, the northern part erodes when the southern part grows (accretes), but the cycle shifts after roughly 200 years. In the 1930's, residents of the Broadwater community and the rest of Hog Island moved to Willis Wharf. The former location of Broadwater is now underwater.22

hurricanes can create new inlets and spits, triggering rapid and dramatic change in barrier island configuration - but longshore drift is dominated by smaller nor'easter storms in winter

Source: National Weather Service Hurricane Ophelia

overwash moves sand, typically from ocean-side to bay-side, so barrier islands migrate rather than drown as sea level rises

Source: National Park Service, Cape Lookout Geologic Activity

Virginia's barrier islands may be changing their shapes in three different patterns. Wallops, Assawoman, Metompkin, and Cedar islands (between Assateague and Parramore) are starved for sand replenishment and retreating westward steadily as sea level rises.

parcel boundaries now extending into the Atlantic Ocean show how much Cedar Island has migrated westward

Source: Accomack County, AccoMap

Further south, Parramore, Hog, Cobb, and Wreck islands are rotating. The southern group, including Ship Shoal, Myrtle, Smith, and Fisherman's islands, are developing straighter shorelines as they move westward.

Metompkin Inlet is a dynamic site, with sediments shifting and channels changing while the inlet has remained open

Source: National Oceanic and Aeronautics Administration (NOAA), Annual Report 1862. No. 16 Metompkin Inlet Virginia

Metompkin Inlet today

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Metompkin Inlet 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (2019)

Fisherman's Island is still growing, from thirty-three acres in 1738 to over 1,850 acres today. Sediments have been derived from both sides of the Delmarva Peninsula. In the 1500's, the Cape Charles paleochannel was blocked by accumulating sediments at Wise Point, as currents from the bay and Atlantic Ocean shoreface created a sand bar on the bottom that built upward until it emerged and grew over 500 years.

The western (Chesapeake Bay) side of Fisherman's Island and the middle section known as "The Isaacs" formed, then merged with each other and the ancestral core of Adams Island to create the current Fisherman's Island.

According to local oral history, that process was accelerated when a ship loaded with linen wrecked on the shallow sandbar. The cargo of linen was removed, but the ship stayed in place. Sand accumulated around it, including during a severe storm in the mid-1870s. Locals called it Linen Island after the original shipwreck, but the name shifted to Fisherman's Island as more and more people started fishing in the waters nearby.23

In 1886, the Federal government leased and later purchased Fisherman's Island. The War Department controlled it initially. In World War II, 300 mines were placed in the shipping channel and controlled by cables stretching out from the island. After creation of Fisherman Island Refuge in 1969, the property was transferred to the US Fish and Wildlife Service in 1973.

In 2003, as a result of Hurricane Isabell, the island increased in size again by over 3%. A storm surge of over 4 feet (plus waves 10 feet high) pushed sand onto Fisherman's Island, especially from the landward/mainland side.24

Fisherman's Island

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

sediments accumulating south of Wise Point formed Fisherman's Island

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Fishermans Island 7.5 x 7.5 topo (2011)

|

Fisherman's Island, morphing over time

Source: Google Earth Engine

Between Assateague and Fisherman's islands, all barrier islands on Virginia's Eastern Shore are migrating towards the west. As sea level rises, the islands are "rolling over" as sand is eroded from the ocean side and redeposited on the bay side during storms. Because land subsidence is greater at Assateague Island (2mm/year) than at Fisherman's Island (1.2mm/year), the northern barrier islands are retreating westward faster than the barrier islands at the southern edge of the Eastern Shore.

The speed at which barrier islands are migrating west may be increasing now by 50%, from 16.5 feet a year in 2020 to 23 feet a year by 2100. Faster sea level rise has eroded away the reservoir of sand and mud which retarded movement. If sea level rises even faster, the migration of the barrier islands would accelerate even more.25

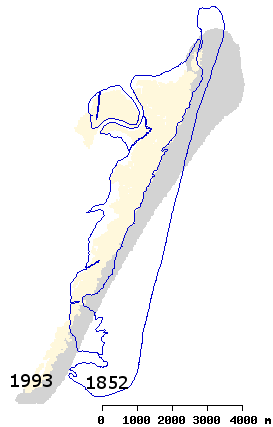

shoreline changes at Hog Island, 1852-1963

Source: US Geological Survey, Coasts in Crisis (USGS Circular 1075)

shoreline changes, 1852-1993

Source: Virginia Coast Reserve, Hog Island Chronosequence

Climate change has contributed to erosion, by allowing the wax myrtle shrub (Morella cerifera) to survive through more winters. The shrub has out-competed the grasses responsible for building sand dunes. Researchers working through the Virginia Coast Reserve Long-Term Ecological Research project concluded in 2018 that barrier islands covered with a shrub forest, rather than sand dunes, are more susceptible to permanent erosion during major storms. They noted:26

wax myrtle (Morella cerifera) on Cobb Island

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Corps of Engineers dredges the Chincoteague Inlet annually to maintain boat access, and dumps the spoil pile off Wallops Island to help protect that shoreline from erosion by major storms. Those sand transfers are temporary adjustments to the natural cycle; the beaches are always moving.

Similarly, "armor plating" the shoreline with jetties, breakwaters and sea walls can only slow the natural geologic process of shoreline erosion. Fixed structures to trap sand in one place cause the waves to expend their energy by moving sand further downstream (south) rather than inland (west) - assuming there is an adequate supply of sand.

groins built at Wallops Island, shown here in 1969, failed to protect the shoreline because there was not enough sand in longshore currents to trap and replenish the beach

Source: Storm Damage Reduction Project Design for Wallops Island, Virginia (p.11)

Wallops Island has $800 million of rocket launching and aviation infrastructure, and a shoreline that has moved 500 feet westward since 1851. A seawall built in 1945-46, and groins built in the next 20 years, provided inadequate protection.

erosion between 1991-2005 threatened the launch facilities on Wallops Island

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement - Wallops Flight Facility Shoreline Restoration and Infrastructure Protection Program (p.9 in Volume I)

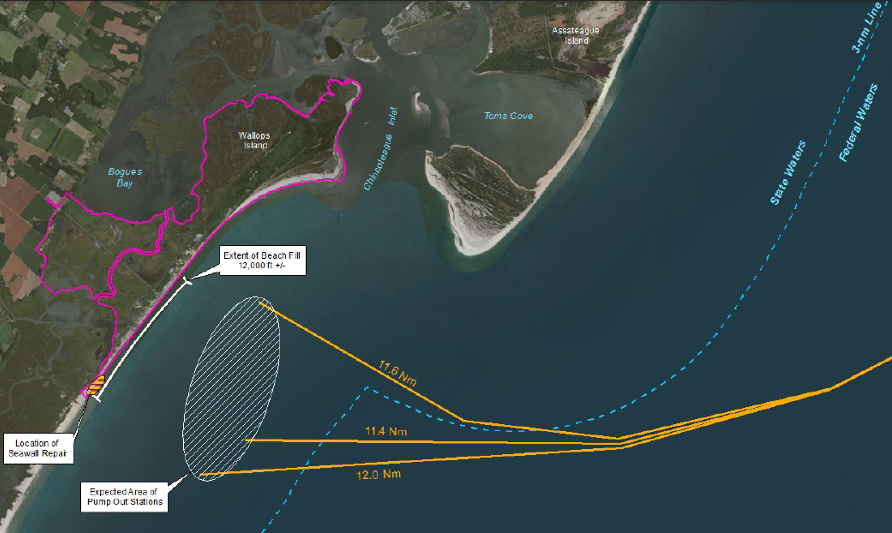

The solution adopted by the Federal government was to install temporary geotextile tubes, then extend the permanent seawall further south and expand the beach.

geotextile tubes provided temporary protection, until the seawall was extended and the beach expanded

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement - Wallops Flight Facility Shoreline Restoration and Infrastructure Protection Program (p.11 in Volume I)

a seawall was constructed at the inland edge of the beach, near the Wallops Island launch pads

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 090613-A-CE999-001.JPG

For the Wallops Island Storm Damage Reduction project, 3.2 million cubic yards of sand was dredged from a shoal in Federal waters between Wallops and Assateague Islands, deposited near the Wallops Island shore, then pumped and spread by bulldozers to widen the beach. Potential sources of sand included the dredge spoils from maintaining the Chincoteague Inlet. A 2002 test of that material revealed that it did not remain near the seawall, but generally diffused throughout the area because the grain size was too small. In addition, costs for dredging and applying the small amount removed regularly from the channel were high, and there was a risk of excavating unexploded ordinance from the seabed.

There were similar problems with the grain size of the silt/clay/sand dredged from the Virginia Inland Passage to maintain the shipping channels between the mainland and the barrier islands along the Eastern Shore, and with potential "borrow sites" east of Wallops Island near the shoreline. Shoals further offshore were identified as the preferred source for the sand replenishment.

offshore shoals were identified as the best source for sand of the right grain size for beach replenishment

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement - Wallops Flight Facility Shoreline Restoration and Infrastructure Protection Program (p.49 in Volume I)

beach replenishment at Wallops involves dredging sand at an offshore shoal, depositing it at a site near the seawall, then pumping the sand onshore

Source: Final Environmental Assessment, Wallops Island Post-Hurricane Sandy Shoreline Repair (June 2013, p.2-3)

between the seawall and the ocean, sand was pumped onshore to expand the beach

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Wallops' Newest Beach

The beach protection project was completed before Hurricane Sandy struck in October, 2012. After Hurricane Sandy washed away much of the replenished beach, the Federal government committed to dredge more sand and repeat the beach nourishment process. Sand was a temporary buffer that was expected to move. When it absorbed the energy of the waves, it successfully protected the infrastructure on Wallops Island for the military base, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport (MARS). The seawall was just the second line of defense, when breaking waves were no longer halted by the beach.

From the beginning, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration planned to replace 800,000 cubic yards of sand every five years. The projected impacts of the No Action alternative were unacceptable:27

large rocks were transported to the Coastal Plain to create the seawall on Wallops Island

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement - Wallops Flight Facility Shoreline Restoration and Infrastructure Protection Program (p.162 in Volume I)

Ocean City (in Maryland) and Virginia Beach require constant sand replenishment ("nourishment") to maintain their current wide beaches. Those two resort communities pump sand from offshore to the beach in front of their boardwalks. That creates a wide recreational beach - until the next series of storms. Local taxes are being invested to fight the natural pattern and perpetuate a big beach as the key attraction for the local community's economy, but Federal and State funding for such projects has been shrinking since 2000.

if you think sea levels are rising and the Town of Chincoteague should be protected over the next 100 years rather than abandoned...

what actions should be taken to protect the barrier island, and who should pay?

Source: US Geological Survey - Global Fiducials Library Data Access Portal, Assateague National Seashore, Maryland

The Nature Conservancy helped Virginia avoid the shoreline maintenance expense along the Eastern Shore. It purchased the marshes and barrier islands, choosing to perpetuate the natural setting and allow erosion/deposition to occur naturally. By minimizing the "built environment" of hotels and recreational facilities on the edge of the beach, The Nature Conservancy eliminated any need to build sea walls or pump sand.

beach replenishment requires extensive modification of the natural shoreline

Source: Final Environmental Assessment, Wallops Island Post-Hurricane Sandy Shoreline Repair (June 2013, p.2-3)

As authorized by the Coastal Primary Sand Dune Protection Act passed by the General Assembly in 1980, special review is required by county Wetland Boards or the Virginia Marine Resources Commission before landowners can build structures that might impact the primary dune line or state-owned beaches. Virginia legislators are traditionally reluctant to limit private property rights, but shoreline development can damage adjacent properties by disrupting the normal migration of sand:28

these houses on Cedar Island were built on solid ground - and then the sand on the barrier island migrated

Source: US Geological Survey, Coastal Change Hazards: Hurricanes and Extreme Storms

Barrier islands are formed from unconsolidated sediments, so rainfall can quickly penetrate the sand. Wind and sun can create a very dry environment, just a few yards from the vast amount of water in the ocean. Barrier island plants must be adapted to drought-like conditions and must tolerate salt spray, since access to fresh water will be intermittent after storms. Shrubs and maritime forests on barrier islands include species such as pine trees, which have waxy coatings on the needles to conserve moisture.

In some depressions, where clay or organic particles create an impermeable layer, freshwater may accumulate. Ponds can provide fresh drinking water to animals, such as the famous herd of wild horses on Chincoteague Island. (The horses do not drink salt water...) Barrier islands also offer valuable habitat for migratory birds, such as the piping plover (which requires overwash fans for nesting habitat):29

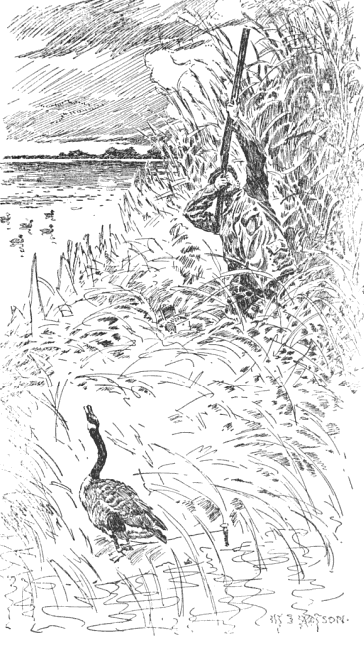

Both recreational and market hunting were common on Virginia's barrier islands until wildlife conservation laws were passed and enforced between 1918-1940. According to one report:30

Hog Island is bracketed by Quinby Inlet and Great Mahipongo Inlet

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Bathymetric Data Viewer

The expansion of steamboat service and railroads after the Civil War stimulated more sportsmen from East Coast cities to travel to the barrier islands to hunt. Forest And Stream published in 1876:31

President Grover Cleveland hunted ducks at the Back Bay Club (Virginia Beach) and Broadwater Club (on Hog Island)

Source: Fishing and shooting sketches, by Grover Cleveland

barrier islands off Eastern Shore (green arrows) and their key access points on mainland (orange arrows)

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Human Impacts

To Sensitive Natural Resources On The Atlantic Barrier Islands On The Eastern Shore Of Virginia - 2005 Report

Conservation of the barrier islands in the Atlantic Ocean off the Eastern Shore is complicated by sea level rise. Sea level rise over the last 50-100 years has removed the accumulated mud and sand which had retarded barrier island retreat.

Even if greenhouse gas emissions are eliminated now, the rate at which the islands are migrating westward will increase substantially. The Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) reported in 2022:32

The December 2021 version of the Virginia Coastal Resilience Master Plan predicted that by 2080:33

storm surges can create new inlets, carving a channel (breach) completely through a barrier island and carrying sand into the bayside

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Hurricane Isabel Impact - Frisco Breach

in 1942, Toms Gut stretched only halfway across Uppards on Tangier Island

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Tangier Island VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (1942)

on Tangier Island today, Toms Gut stretches across Uppards and storm erosion is enhanced by opening on west side

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

barrier islands south of Chincoteague Bight,

on Atlantic Ocean side of Eastern Shore

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration

storm surges can move barrier island sediments from multiple directions - including ebb-tide deposits from bay-side

(in the Assateague Island 1998 Northeaster, waves off Ocean City were more than 20' high)34

Source: US Geological Survey, Systematic Mapping of Bedrock and Habitats along the Florida Reef Tract-Central Key Largo to Halfmoon Shoal (Gulf of Mexico) (Professional Paper 1751, Figure 101)

the National Park Service artificially widened the beach on Assateague Island in 2002

Source: National Park Service, Beach Nourishment

Assateague Island, showing growth of Tom's Cove at southern end

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Astronaut Photography of Earth

barrier islands have a core, an overwash beach on the high-energy ocean side, wash-arounds where sand accumulates after storms, tidal marshes on the low-energy bay side, and ponds where fresh water is trapped in depressions (plus inlets that open/close due to storms)

Source: National Park Service, A hydrogeomorphic map of Assateague Island National Seashore, Maryland and Virginia (Figure 9, p.16)

Tangier Island had a mile-long southern spit

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Tangier VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (1968)

Tangier Island has lost its southern spit

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online