aquaculture on submerged lands leased through Virginia Marine Resources Commission at Cherrystone inlet, north of Town of Cape Charles

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

aquaculture on submerged lands leased through Virginia Marine Resources Commission at Cherrystone inlet, north of Town of Cape Charles

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The state owns the bottom of the Outer Continental Shelf for the first three miles offshore, and claims title to the bottom of rivers and tidewater areas in the state up to the Mean Low Water line (the mean low-water mark, the line of low tide averaged over 20 years):1

above the mean low-water mark, public agencies have to purchase property and create parks to make beaches open to the public (City of Hampton)

Congress passed the Submerged Lands Act in 1953, after a series of Supreme Court decisions in 1957-50 declared that states had no ownership rights in submerged lands. Under that law, in Virginia has clear title to the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay, plus submerged lands on the Atlantic Coast offshore up to three "geographical miles" (essentially nautical miles 6,087 feet long).

Virginia controls submerged lands under the Atlantic Ocean, for three miles offshore

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), MarineCadastre.gov

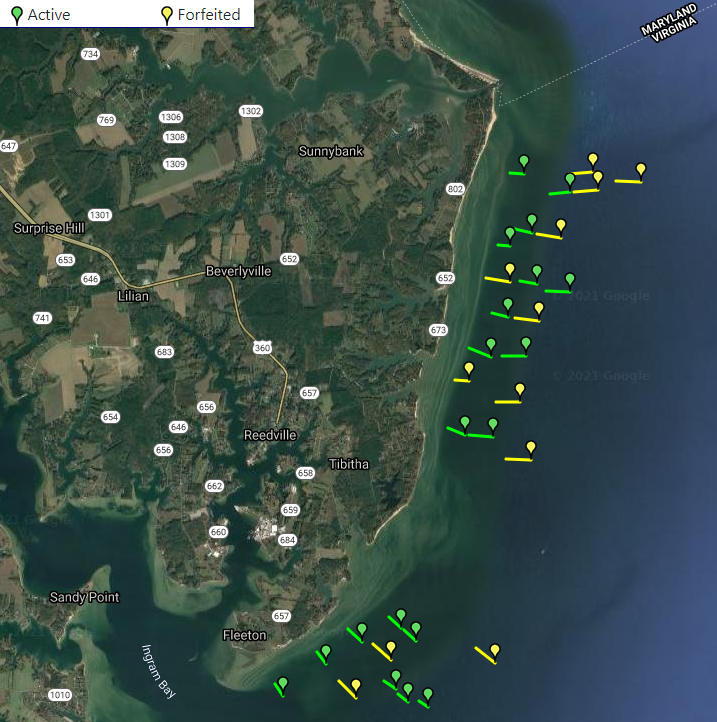

Owners of shoreline property must obtain state permits to build large piers, raise oysters/clams, dredge for sand, install phone/power lines underwater, or build offshore platforms for oil drilling/windmills within three miles of the coast. Pound nets used to capture fish rely upon poles driven into the bed of the Chesapeake Bay, so permits must be obtained from the Virginia Marine Resources Commission.

Virginia Marine Resources Commission permits are required for installing pound nets in the Virginia portion of the Chesapeake Bay

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, Chesapeake Bay Online Pound Net Map

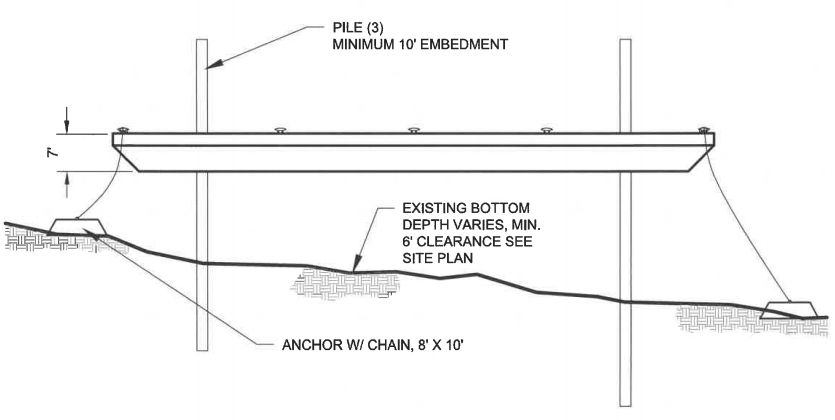

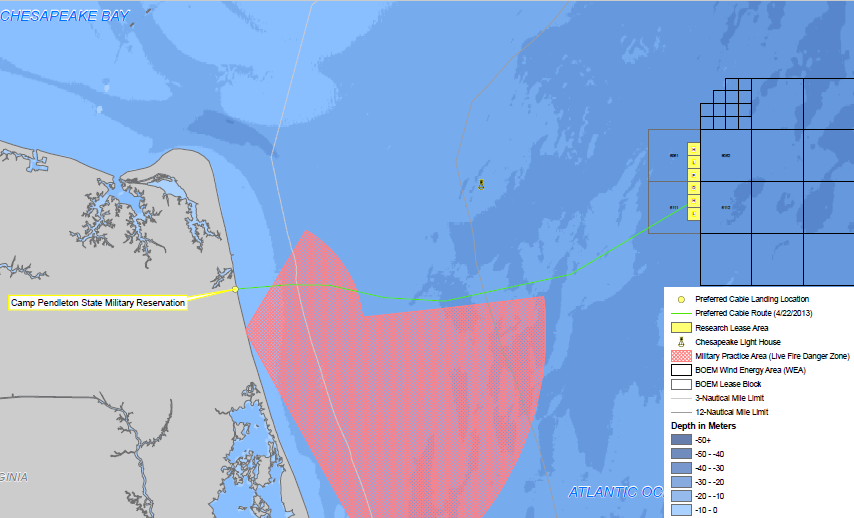

In 2015, after the Virginia Electric and Power Company (a subsidiary of Dominion) obtained a lease from the Federal government to build test wind turbines 24 miles offshore for the Virginia Offshore Wind Technology Advancement Project, the utility company planned for its 34.5 kV submarine power cable to come ashore at the Camp Pendleton State Military Reservation in Virginia Beach. That required crossing 21 miles of Federally-owned Outer Continental Shelf plus three miles of the Commonwealth's territorial sea under the jurisdiction of the Virginia Marine Resources Commission. The cost to lease 18,228 feet of State-owned submerged bottomlands was $54,684 (plus a $100 permit fee), at the standard rate of $3.00 per linear foot.

Even state agencies must get permits for use of submerged lands. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources wanted to place temporary barges next to the south island of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel for five years, starting in 2021. The barges were intended to provide nesting habitat for seabirds displaced by construction activities, as two new tunnels were built.2

the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources needed a permit from the Virginia Marine Resources Commission to use submerged lands at Hampton Roads to anchor barges used for temporary bird habitat

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, permit application by Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (December 21, 2020)

Federal authority over navigation, established in the US Constitution, is not reduced by the transfer of ownership. Federal approval for installing structures in navigable waters is still required, even if the submerged lands are state-owned, in order to protect water-based commerce.

Submerged land in the Atlantic Ocean more than three miles offshore is owned by the Federal government. Federal officials have exclusive control over use of the bottom of the ocean more than three miles offshore to issue permits for mining sand, installing wind turbines, etc. In Federal waters off the coast of California, Federal officials have issued leases for aquaculture operations. All aquaculture leases in Virginia involve state-owned lands and water; no aquaculture leases have been issued off the Virginia coast for Federal submerged lands.3

In 1991, Virginia used its control over submerged lands at Hampton Roads to block plans of US Army Corps of Engineers to expand the Craney Island dredge disposal site to the west, ultimately reaching a compromise to widen the Craney Island on the eastern side instead.

the Virginia Offshore Wind Technology Advancement Project included bringing electricity generated by offshore wind turbines to the onshore grid via submarine cables, and in 2015 the Virginia Marine Resources Commission leased submerged land under state control for the buried powerline (green line) at $3.00 per linear foot

Source: Dominion, "Virginia Offshore Wind Technology Advancement Project," Project Overview

The Submerged Lands Act, passed by the US Congress, refers to the "line of ordinary low water" when establishing the boundary of the state/Federal control offshore, but that law did not determine the ownership of property rights along the Virginia shoreline. Instead, Virginia state law and the Public Trust Doctrine determine the boundary between private vs. state property at the water's edge.

In many states, the limit of private property is interpreted to be the high water mark adjacent to a tidal waterway. Where the high water mark adjacent to a tidal waterway is the limit of private property, public agencies retain ownership of the narrow strip between the high water mark and the line of ordinary low water, which may be covered with actual water at high tide. In states that actively manage public ownership of that strip, there is public access for walking, fishing, and landing boats on the shore below the high water mark:4

Virginia (like Delaware, Maine, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania) takes a different approach. Virginia law authorizes private landowners to control land down to the Mean Low Water mark, including land that may be submerged at high tide. Those property rights were made clear in an 1819 law passed by the General Assembly.5

Control of the shoreline down to the Mean Low Water mark allows owners of riverfront property to block the public from fishing from the riverbank in front of their homes, and blocks people from strolling along the riverbank. No Trespassing signs are legitimate on the shoreline of many Virginia rivers, and property owners can call on county sheriffs to enforce the law and block public use above the Mean Low Water mark. An owner of a house on the beach has the right to control access on the beach, down to the Mean Low Water mark, unless public agencies have acquired access rights.

In 2015, a property owner in Norfolk erected a fence down to the high water mark, excluding people from his private property. A set of large rocks placed below the high water line, outside the fence, made it very difficult to walk around the fence in the Chesapeake Bay water. Tourists and neighbors were blocked from their traditional walks along the shoreline of Willoughby Spit, and even city police patrolling the beach had to detour around the fenced-off parcel.

Nearby waterfront homeowners complained, saying "It's not being neighborly" and "It's made everybody mad." The landowner who fenced the property responded bluntly:6

The fence was legal. The rocks remained a matter of dispute; their placement may have violated Virginia's Coastal Primary Sand Dunes and Beaches Act.

A 2016 beach replenishment project was expected to end the problem by widening the beach. Norfolk was required to acquire an easement guaranteeing public access to the additional land created by the beach replenishment project. Regulations of the Virginia Marine Resources Commission for "Placement of Sandy Dredged Material along Beaches in the Commonwealth" say:7

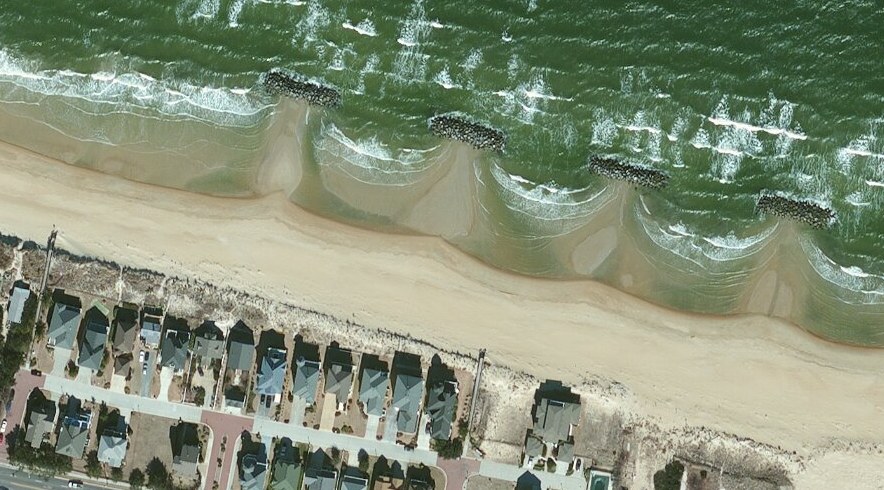

before authorizing beach replenishment projects, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission requires that the existing land located below Mean Low Water will remain public after the shoreline is altered

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

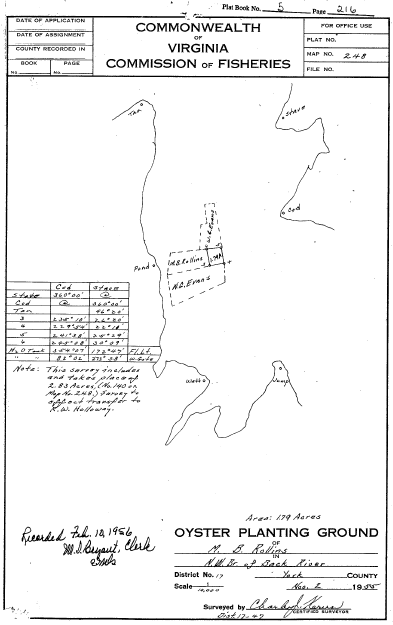

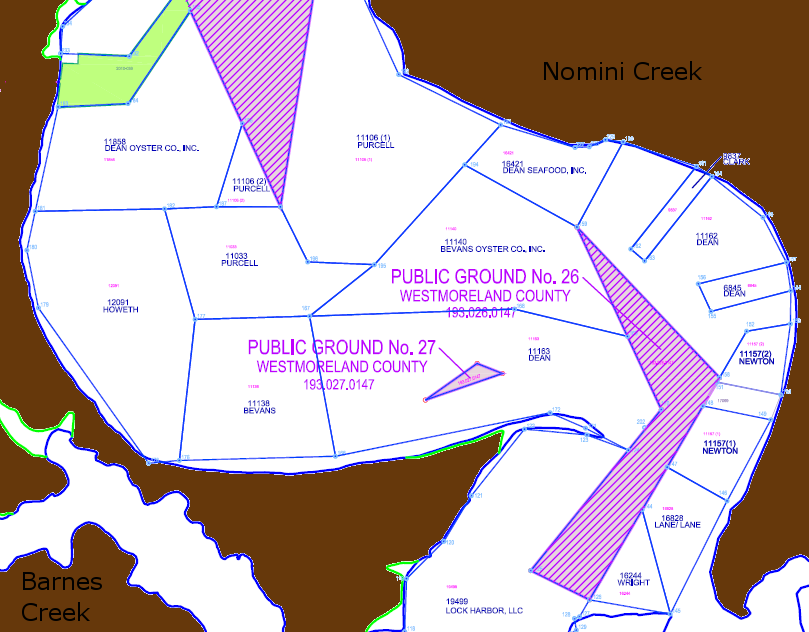

Virginia has transferred some of the state's property rights to land that are completely submerged, below the Mean Low Water mark, by issuing leases to the beds of tidewater rivers and the Chesapeake Bay. Those submerged lands are still owned by the state, but specific parcels have been leased by the Virginia Marine Resources Commission to individuals, businesses, and public agencies seeking to grow clams/oysters.

Parcels of submerged lands in tidal waters that have been leased by the Virginia Marine Resources Commission for restoration of oyster beds are known as "private rocks." The person with the lease pays the cost to barge in old oyster shells to create a hard bottom that will attract new oysters, and only the person with the lease is authorized to harvest the oysters that grow on "private rocks."

The City of Virginia Beach funds dredging projects to improve/maintain navigation on local waterways. When dredging will impact private oyster leases, the city has to purchase the leases. Private property rights, for submerged lands or otherwise, are protected by Article I, Section 11 in the Constitution of Virginia:8

The City of Virginia Beach has dredged through oyster leases in the Lynnhaven River. The Virginia Department of Health previously had "condemned" the leases, prohibiting harvest from them because bacteria levels were too high. The prohibition of oyster harvesting for heath reasons may have affected the value of the leases, but the city was still obliged to acquire them. Though the same words are used, "condemnation" for health reasons is not equivalent to "condemnation" for real estate acquisition.

Public agencies also must obtain a lease from the Virginia Marine Resources Commission for the right to plant oysters for restoration projects. The City of Virginia Beach has purchased existing leases from the owners for some of its oyster restoration projects.

The city was unable to obtain a state permit to use submerged land and build a flood mitigation project in Bonney Cove of Back Bay. The $46 million project included construction of 41 terraces to create sheltered habitat in which submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) would grow. The terraces and underwater grasses would block flooding when southern winds pushed water from Currituck Sound into Back Bay.

When the Bonney Cove project was planned in 2020, the submerged land was barren. By 2025, however, submerged aquatic vegetation had returned and the Virginia Marine Resources Commission refused to authorize disturbance.9

For areas not already under lease, cities, counties, the US Army Corps of Engineers, or conservation groups still must pay the standard rate ($1.50 an acre per year) to the Virginia Marine Resources Commission for the right to use submerged land owned by the state.

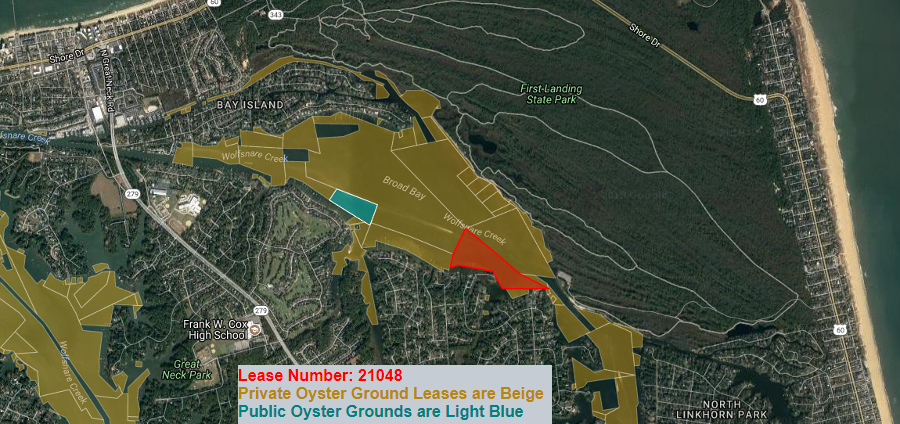

Virginia Beach acquired Lease #21048 for oyster restoration in Broad Bay

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, Maps: Oyster Ground Lease

Under the Public Trust Doctrine, the transfer of submerged land from initial government ownership to private ownership did not transfer 100% of the property rights. The public interest in that land must be protected forever, so a grant of submerged lands was revocable (in contrast to grants of lands above the waterline).

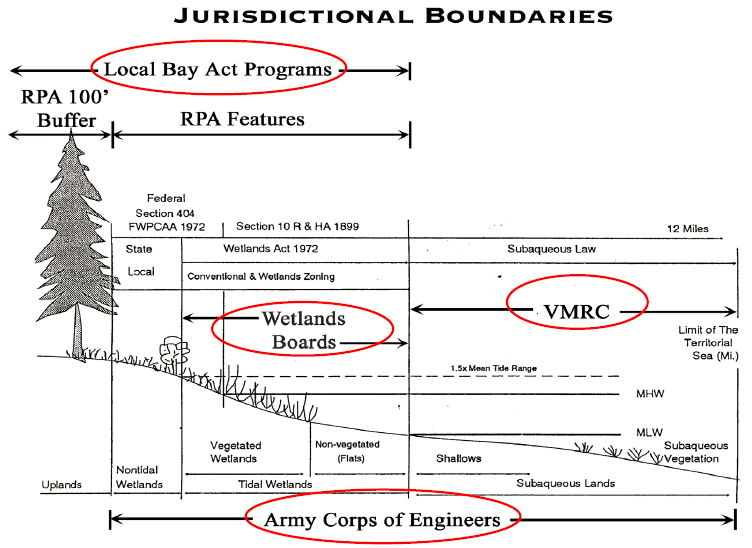

State and Federal law still affect the use of private property in Virginia all the way down to the Mean Low Water mark. For example, local zoning constrains development, the US Army Corps of Engineers has regulatory responsibility for permitting the dredging and filling of wetlands above the water line, and the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) oversees structures built or impacting the submerged lands. The Virginia Marine Resources Commission also oversees local wetlands boards that regulate alteration of tidal wetlands from "low tide inland to a point 1.5 times the mean tide range."

The Code of Virginia states defines the area over which the Virginia Marine Resources Commission has responsibility:10

responsibility of different government agencies at the water's edge in Virginia (VMRC jurisdiction is limited to Virginia's portion of the Territorial Sea, 3 miles offshore)

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Living Shorelines: Development of a General Permit & Integrated Guidance

The Virginia Marine Resources Commission manages the 2,300 square miles (approximately 1,472,000 acres) of tidally-influenced submerged lands claimed by the state. The agency notes that this "is an area larger than the entire State of Delaware."11

On submerged land claimed by Virginia, the state commission approves structures such as boat docks, piers, and seawalls. The Virginia Marine Resources Commission also approves "encroachments" by utility companies for power lines and pipelines buried underwater.

Use of the state-owned submerged land, even a powerline crossing in in the air, requires a royalty payment to Virginia. In 2015, the rate was $3.00 per linear foot. When Columbia Gas Transmission proposed to build a new natural gas pipeline across the South Fork of the Shenandoah River in Page County, it was charged $729 (plus a $100 permit fee) for its use of 243 linear feet of the river bottom. The Virginia Marine Resources Commission charged Dominion Energy $170,000 for use of the bottom of the James River to support 17 towers carrying the new Skiffes Creek transmission line from the Surry nuclear power plant to the Peninsula.

In 2023, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission created a general permit to streamline the authorization of utility lines crossing either above or below the State-owned subaqueous bottom. The new process eliminated the public interest review step for each project, speeding approval by 90 days but reducing transparency in the decision making process. The change was justified because:12

When Dominion Energy planned to install a 34.5kV submarine electrical transmission cable from offshore wind turbine generators, the last three miles to reach the shoreline at Camp Pendleton crossed state-owned submerged bottomlands. The Virginia Marine Resources Commission staff determined the utility should pay a royalty of $3.00 per linear foot. Since the transmission line would affect 18,228 feet of bottomland, the total royalty was $54,684 (plus the $100 permit fee).

Approval by local officials is required for the stretch of underwater cables that come onshore. Getting a state permit for use of submerged land does not ensure local officials will support the onshore component of a project.

The Kitty Hawk Wind Offshore Wind Project planned to bring electricity from wind turbines off the North Carolina coast via a 27 mile underwater cable to the grid in Virginia Beach. The cable landing was planned in Sandbridge, but local residents objected to the projected disruption of construction. There were also concerns regarding perceived health risks from the electromagnetic fields. In 2023 the Virginia Beach City Council notified the developer of the offshore project, Avangrid Renewables, that the likelihood of ciy approval was low.

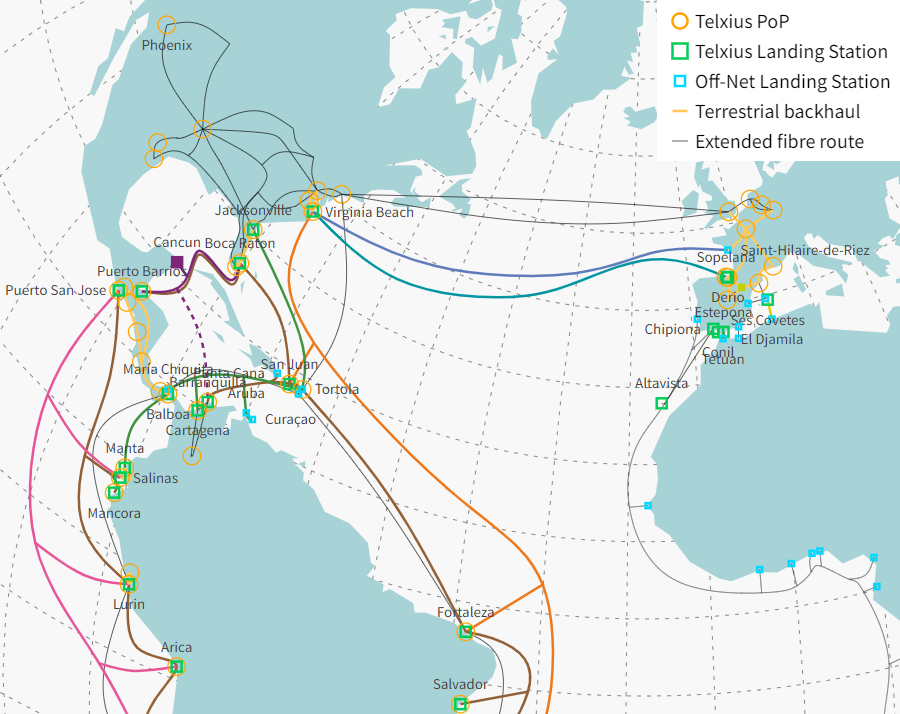

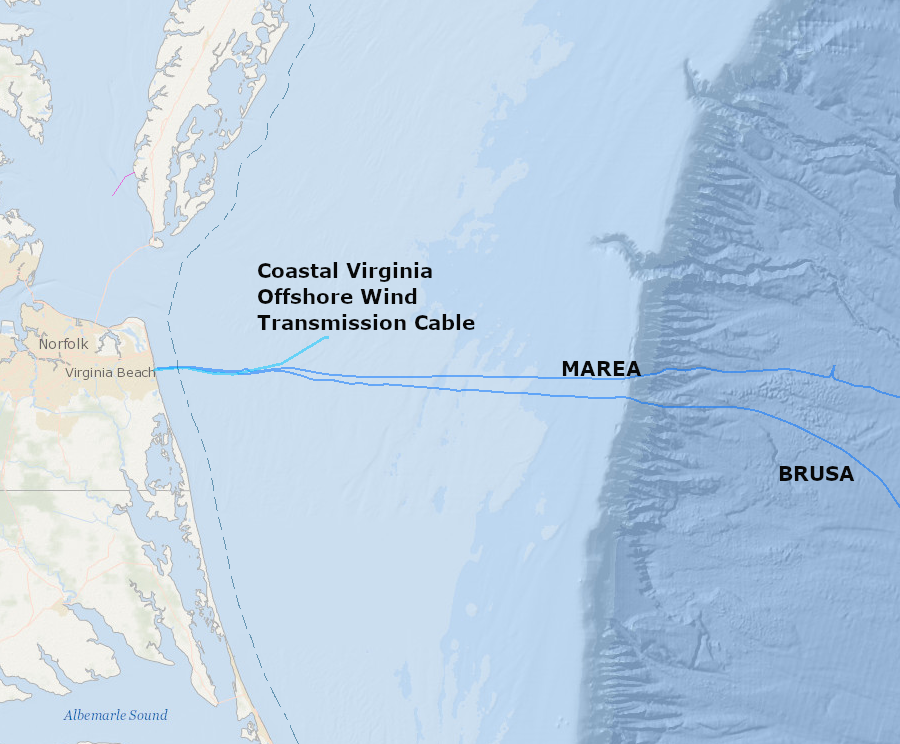

However, the Virginia Beach City Council approved four subsea communication cables coming ashore at Sandbridge. The city had previously approved landing sites at Camp Pendleton for the MAREA and BRUSA communication cables. By 2024 there were 800,000 miles of subsea telecommunications cables, part of 600 different systems.

The Virginia Beach Cable Landing Station became the destination for the MAREA, BRUSA, SAEx1 and Dunant submarine communication cables, linking North America to South America and Europe. International traffic on Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and many other platforms travels through the ground at Virginia Beach as well as through New York, New Jersey and Miami.13

multiple major subsea communication cables connect to the Virginia Beach Cable Landing Station

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online and Telxius, Network Map

three major cables are authorized to cross Federal and state submerged lands off Virginia Beach (dotted line is Submerged Lands Act 3-mile boundary)

Source: Mid-Atlantic Ocean Data Portal

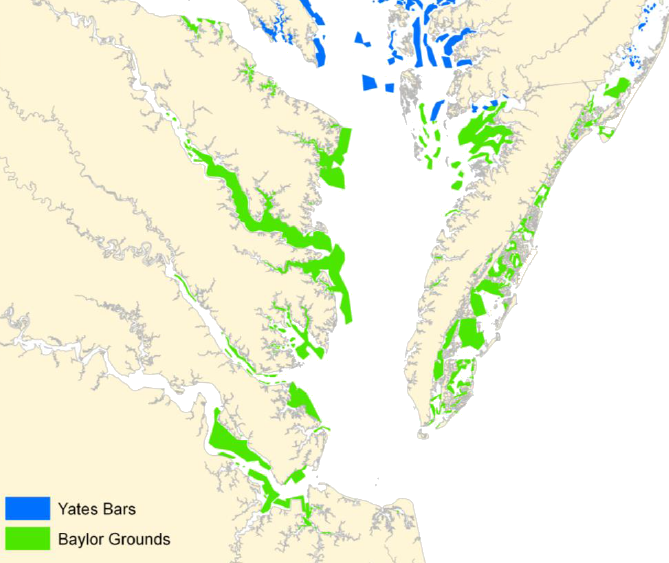

The bottom of the Chesapeake Bay is especially valuable real estate for clams and oysters. After determining the boundary between Maryland/Virginia in 1877, Virginia arranged for James Baylor from the US Coast and Geodetic Survey to identify the location of shellfish beds in 1892-94. State officials used the surveys to determine where submerged lands without natural oyster beds could be leased. By protecting existing shellfish beds, individuals would have an incentive to restock the barren sites for private use without closing productive sites that watermen could continue to harvest.

Virginia committed to maintain public access to the 232,016 acres where the Baylor surveys identified oysters were still reproducing naturally in 1894. On those "public rocks," watermen would retain the opportunity to harvest naturally-growing shellfish. Today, Article XI, Section 3 in the state constitution draws the key distinction between barren submerged land vs. natural oyster beds:14

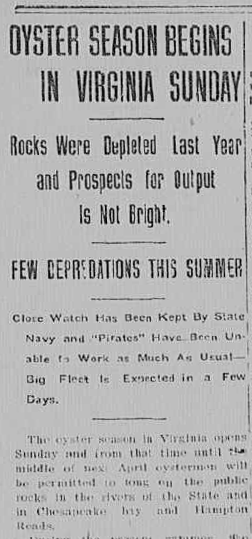

By the end of the 19th Century, it was obvious that the Virginia oyster population had been reduced dramatically by overharvesting and habitat destruction. Maryland tried restoring oyster reefs and immediately allowing public harvest. Watermen would quickly scoop up whatever new oysters were grown on Maryland's restoration sites, forcing the state to restore/restock again.15

1907 newspaper report on expectations of oyster harvest on public rocks

Source: Newport News Daily Press (September 12, 1907, provided by Library of Congress)

In contrast, Virginia began to lease submerged lands to individuals who would create new reefs and stock them with oysters. Those "private rocks" were barren of shellfish, separate from the "public rocks" where oysters/clams were still surviving (as defined by the Baylor Survey in the 1890's).

The private leases issued by the state are still intended to incentivize individuals to restore former oyster beds in Tidewater creeks. Anyone with a lease from the state can place old oyster shells on the bottom (or suspended above the bottom in bags/cages) and restock oysters to create a new oyster reef. Those with a lease for private rocks have exclusive authority to harvest whatever grows on their restored site; aquaculture investment is rewarded.

In 1876, the Supreme Court clarified in the McCready v. Virginia lawsuit that Virginia's property right to its submerged lands allowed the state to ban Marylanders and other non-Virginians from planting or harvesting oysters on the bed of tidal rivers:16

Of course, trespassing and poaching of oysters occurred. "Oyster wars" between watermen spurred both Virginia and Maryland to establish an Oyster Navy to enforce state regulations. The history of oyster mismanagement through the 1950's, until disease nearly exterminated the commercial value of oyster harvesting, is just as colorful as the tales of cattle rustling in the Wild West.17

lease for private oyster bed in York River, and boundaries of public/private oyster beds in Nomini Creek

Sources: York County and Virginia Marine Resources Commission

The Baylor Survey of the 1890's is still a guide to locating new public oyster restoration projects. To protect new oyster reefs, Virginia has established oyster sanctuaries where harvesting is prohibited. The definition of property rights, based on state ownership of the bay bottom, has been essential to Virginia's approach to restoring the species.

Private aquaculture leases for growing oysters and clams require approval by the Virginia Marine Resources Commission. Boaters, adjacent "highland" property owners, and even members of the general public may object to the placement of cages, pumps, pipes, and other infrastructure for aquaculture operations. Construction of docks and piers, especially those with vista-blocking roofs, and seawalls that alter the shoreline also may draw objections. The commission has refused to approve or renew some applications.

C.C. Yates mapped Maryland's Natural Oyster Bars between 1906-1912, after the Baylor surveys in Virginia documented oyster habitat in 1892-1894

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Chesapeake Bay Oyster Recovery: Native Oyster Restoration Master Plan - Maryland and Virginia

In 2012, a report to the General Assembly concluded that management of the bottomlands on the Atlantic Ocean side of the Eastern Shore should be modified. In contrast to the Chesapeake Bay, most remaining oyster beds on the seaside of the Eastern Shore were located between the high and low tide levels, as small "fringing reefs along the edge of marshes or as patch reefs on intertidal mud and sand flats" and not within the boundaries of the Baylor Grounds. As a result, the existing oyster beds could be leased and controlled by private parties, while the Baylor Grounds - supposed the valuable locations where most oysters would be kept accessible for public harvest - were not suitable for restoration.

Key findings of the report included:18

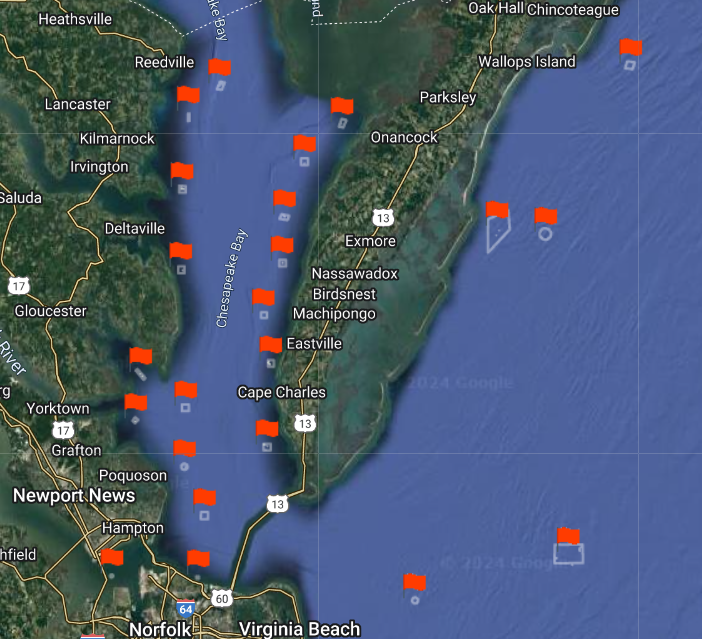

In addition to artificial reefs created for oysters, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) has authorized 23 artificial reef sites (18 inshore and 5 offshore) on state-owned submerged land. The artificial reefs create habitat not otherwise available where the bottom is sandy, muddy, and flat. The artificial reefs are intended to benefit primarily fish, while oyster reefs support other species as a side benefit.

Reefs have been constructed by sinking Liberty ships, tires, and specially-constructed concrete "igloos" and tetrahedrons. In the Mid-Atlantic, there are more than 130 artificial reefs.19

as of 2024, there were 23 artificial reefs off Virginia coastlines

Sources: Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC), Artificial Reefs

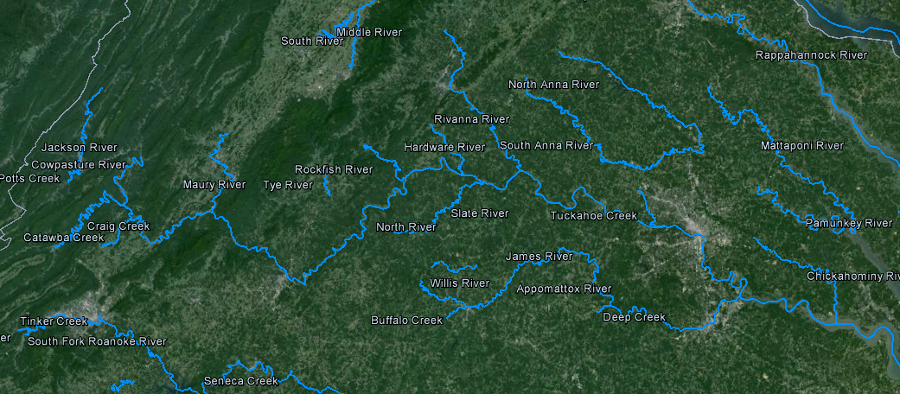

In addition to claiming tidal waters, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission is responsible for non-tidal river beds. Based on the Martin v. Waddell decision by the Supreme Court in 1842, codified by Congress in the Submerged Lands Act in 1953, Virginia asserts title to submerged river bottoms on major rivers and streams that were suitable for commercial traffic using boats/canoes in the colonial era.

Actual commercial use does not have to be documented prior to 1776, so streams in the western part of the state where settlement occurred late still qualify as "navigable." Based on an Attorney General's opinion issued in 1982, the state claims ownership of stream bottoms that were:20

The Virginia Marine Resources Commission asserts authority to regulate streams west of the Fall Line as well as within Tidewater. It uses a definition of navigability based on watershed size and streamflow volume, rather than documented historical use:

In addition, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission claims authority to manage non-tidal streams that are "non-navigable-in-fact:"

It is common for utilities to place pipes across small streams, and for riparian landowners to drill a support below the Mean Low Water line in small perennial streams to support a boat dock. Even in western Virginia, those utilities and riparian landowners must obtain a permit from the Virginia Marine Resources Commission and pay a small rental fee to encroach on state-owned submerged lands.

The state has the capacity to monitor permits and to require compliance. In 2021, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission fined Dominion Energy and its contractor installing a submarine cable in the Rappahannock River adjacent to the Route 3 Robert O. Norris Bridge. The shellfish manager for the Commission's oyster replenishment program observed that a work platform had been installed too close to a natural oyster bed, and the underwater jetting to create a trench for the cable was covering oysters with sediment.

In addition to the fine, Dominion was required to pay $20,000 per acre for the unpermitted use of the riverbed for the platforms, to create a bubble curtain between the platform and oyster bed during underwater jetting operations, and to perform those operations only during the ebb (outgoing) tide so sediment would be transported away from the oyster bed. The annual royalty rate for the temporary encroachment of the work platforms while in the river had been just of $0.20 per square foot.21

The commission's jurisdiction over state-owned bottomlands includes streams within all river basins, and extends from the eastern edge of the territorial sea in the Atlantic Ocean to Cumberland Gap. No distinction regarding the claim of jurisdiction is made between lands east or west of the Fall Line.

Not every stream bottom is regulated as state-owned submerged land. The land underneath ephemeral and intermittent (as opposed to perennial) streams is assumed to belong to adjoining property owners. The bottom of small streams - those with a watershed less than five square miles, or with a mean annual flow less than five cubic feet per second - also belongs to adjoining property owners.

Such streams may still be affected by local land use controls, and the Chesapeake Bay Regulations issued by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) will still require streamside buffers along perennial streams in Tidewater jurisdictions, but there is no oversight from the Virginia Marine Resources Commission for the smallest perennial streams or for intermittent and ephemeral streams.

navigable river sections in Virginia, as claimed by the Department of Game and Inland Fisheries

Source: Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Inland - Navigable Waters (displayed in Google Earth)

The submerged land beneath lakes in Virginia is also exempt from Virginia Marine Resources Commission jurisdiction, except perhaps for the two natural lakes in the state. The state has not asserted a claim to the bottom of Lake Drummond or Mountain Lake.

In 2008, Mountain Lake drained naturally. That process, apparently triggered when sediments shifted and uncovered natural crevices in the lake bottom, was unexpected. Even more surprising was the discovery of the skeleton of a man who had drowned in 1921. The Virginia Department of Historic Resources did not assert responsibility for overseeing the excavation or removal of artifacts from the lake bottom.

In 2013, the owners of the Mountain Lake Hotel used bulldozers to plug up the holes that were causing the lake to drain naturally. The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality and US Army Corps of Engineers chose not to get involved, or require a permit under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act. The Virginia Marine Resources Commission did not require any permit or authorization, reflecting the omission of "lake" from its guidance:22

When Smith Mountain Lake was created by damming the Roanoke River, the Appalachian Power Company did not acquire full fee title to all the land submerged beneath the new artificial lake. The utility purchased flowage easements and paid landowners for the right to drown their fields and forests, and the permit for the dam issued by the Federal Energy Regulatory Authority under Section 10(a)(1) of the Federal Power Act required the utility to regulate docks and other development on the shoreline "to protect the project's recreational, scenic, environmental and other public uses" - but landowners retained all other rights.23

Direct access to the lake increases the value of the parcels on the shoreline, and a dispute between two riparian landowners led to a Virginia State Supreme Court decision in 2001 that the state did not assert any claim to lands submerged beneath artificial lakes.

The Smith Mountain Lake Yacht Club objected to an adjacent landowner building a dock that extended into the lake, over land that was included in the deed to the yacht club. The adjacent landowner claimed Smith Mountain Lake was navigable; therefore the state, not the yacht club, controlled the submerged bed of the lake.

The Virginia Supreme Court ruled that the General Assembly had asserted control over "All the beds of the bays, rivers, creeks and the shores of the sea," but omitted any claim to the land submerged beneath artificial lakes. By listing other types of water bodies but omitting "lakes," the state had limited its authority to just those other types of water bodies.

The creation of Smith Mountain Lake and Leesville Lake flooded private land, but did not transfer authority over that flooded land to the state government. Virginia has authority to regulate activities on the lake itself, so the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries can issue tickets for boating under the influence of alcohol. Because the state does not claim jurisdiction over the bed of submerged lakes, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission could not issue a permit or charge a fee for use of the submerged bottom of Smith Mountain Lake - it remained private land, as is all the land beneath other lakes in Virginia.24

the Virginia Marine Resources Commission plays no role in managing development along the shoreline of Smith Mountain Lake, because the state of Virginia does not claim jurisdiction over lands submerged beneath artificial lakes

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Another constraint on the authority of the state to manage subaqueous lands affected by shoreline development is the Federal government's primacy when maritime law is involved. When the Chincoteague Inn attached a barge to its building to expand its waterfront restaurant seating capacity, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission claimed the barge was above the state-managed bottom and a state permit was required. Lower courts defined the floating platform as a "vessel" engaged in the public right of navigation, and said Federal maritime law preempted the state's authority to order the platform's removal.

In 2014, the Virginia Supreme Court ruled that converting the public space into a restaurant was "an 'encroach[ment] upon or over' state-owned subaqueous bottomland." The long-term static location, serving as a restaurant, disqualified it from having the rights of a vessel to travel through navigable waters. A dissent in that opinion suggested that granting the state agency authority would grant excessive authority to the Virginia Marine Resources Commission, and:25

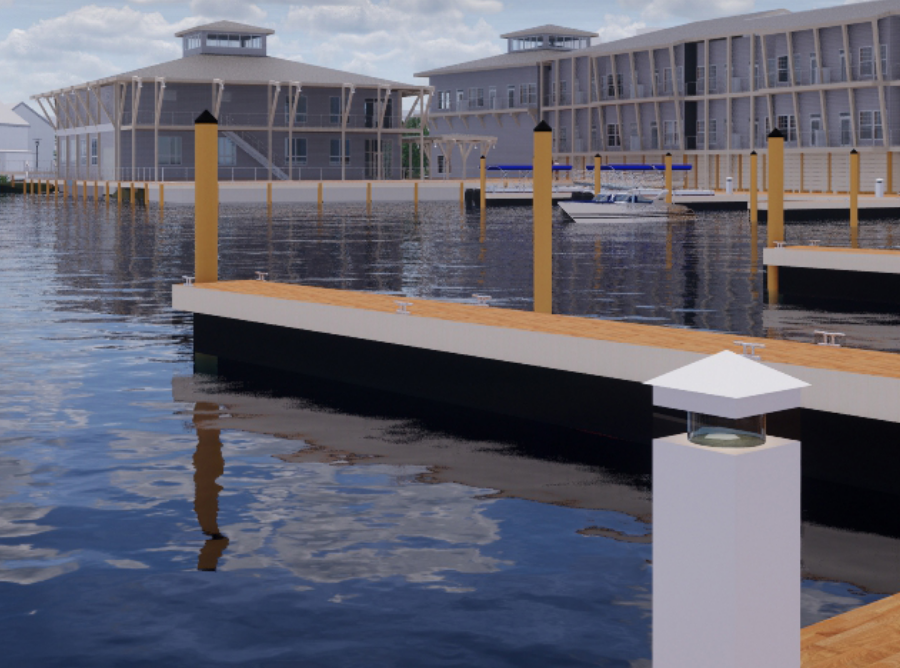

In 2021, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission decided that a $40 million redevelopment at Fort Monroe was a "governmental activity" that did not require a permit for use of 95,000 square feet of state-owned bottomland. The Fort Monroe Authority had invited proposals for adaptive reuse of former US Army buildings that were not included in the Fort Monroe National Monument.

The authority endorsed the 37° North project, which included replacing the 300 slips and timber wave screen at the Old Point Comfort Marina with a new floating dock. Those facilities, plus a new 90-bed hotel, pool and deck built over the water, would impact 28,000 more square feet of bottomland than the existing facilities. The only commissioner to object said:26

Other members of the Virginia Marine Resources Commission agreed with the chair's perspective that the Fort Monroe Authority was responsible for the project, not the private developer:27

the Virginia Marine Resources Commission decided that a new marina and development over water at Fort Monroe was a governmental activity which required no permit for use of state-owned bottomland

Source: Pack Brothers Hospitality, 37° North

The state's claim to both tidal and non-tidal river beds has been challenged by property owners who can trace their title back to grants issued before 1802 (in Gulf of Mexico watersheds) or 1792 (in Atlantic Ocean watersheds). Landowners claiming King's Grants/Crown Grants assert that those grants issued by the colonial/state government conveyed complete title, including submerged lands, until the Virginia General Assembly limited land grants to just the land above mean low water lines.

In 1983 the Virginia Marine Resources Commission sought to issue an oyster lease for a parcel of submerged land on the bottom of Carter's Cove in Lancaster County. Some local landowners objected, claiming they owned submerged land under land patents for 2,160 acres issued originally by Gov. William Berkeley to John Carter on August 15, 1642.

Lawyers representing the state objected to the claim that the English monarchs could transfer ownership of submerged lands without an Act of Parliament, citing the Public Trust Doctrine and asserting that boundaries of colonial grants ended at the high-water mark. The Virginia Supreme Court ruled against the state's claim and determined royal land grants could include creek bottoms:28

The court decision retained the limitation that "the waters over these submerged lands remain highways for passage and navigation by the public."

in 1983 the Virginia Supreme Court ruled that English monarchs were entitled to issue land grants that included the bottom of Carter's Cove (red circle, above), transferring the land below the high-water mark out of public ownership

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Under the Public Trust Doctrine (jus publicum), the state of Virginia allows public use for navigation, fishing, hunting, and collecting shellfish on state-owned lands below the Mean Low Water mark. However, public access to riverbeds and submerged lands is not guaranteed when submerged land is not owned by the state.

Private landowners with land records proving pre-1792 grants in the Atlantic Ocean watershed, or pre-1802 grants in the Gulf of Mexico watershed, may assert ownership of land underneath rivers and creeks and block public access on both tidal and non-tidal creeks. Landowners with private property on - and possibly under - multiple streams located both east and west of the Blue Ridge have contested the rights of the public to step on the land below the Mean Low Water mark when kayaking, canoeing, and fishing.

A determination that a stream is navigable ensures public use of the water, but Virginia courts have determined that submerged lands below navigable rivers may be private property. Legal disputes continue regarding the rights of those landowners citing Kings Grants (also known as Crown Grants) to block what they describe as trespassing on privately-owned submerged lands.

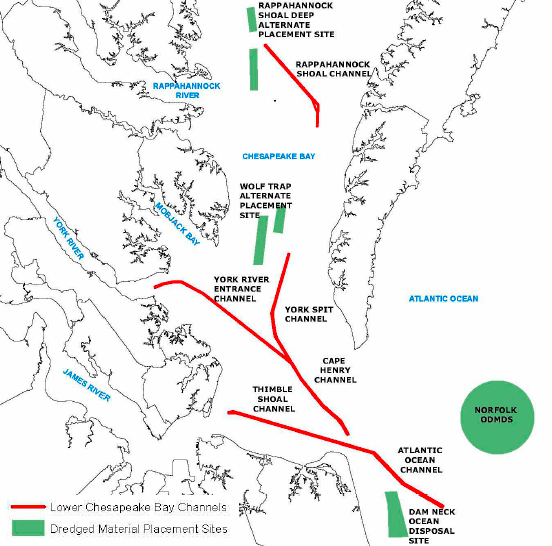

two sites for disposal of materials dredged to maintain depth of shipping channels at Hampton Roads are outside the 3-mile boundary and thus controlled by the Federal government, the Dam Neck Ocean Disposal Site and the Norfolk Ocean Dredged Material Disposal Site

Source: National Marine Fisheries Service, Maintenance of Chesapeake Bay Entrance Channels and use of sand borrow areas for beach nourishment

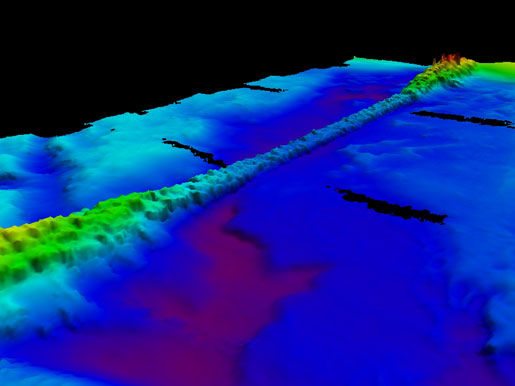

submerged riprap on bottom of Chesapeake Bay, protecting Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOS Responds to November 2009 Nor'easter

most of the bottom of Nomini Creek is covered by private oyster leases

Source: Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program, Virginia Coastal Geospatial and Educational Mapping System (GEMS)