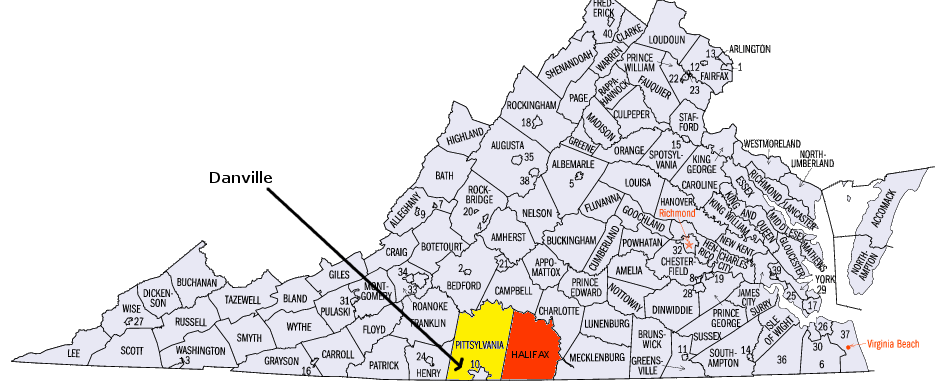

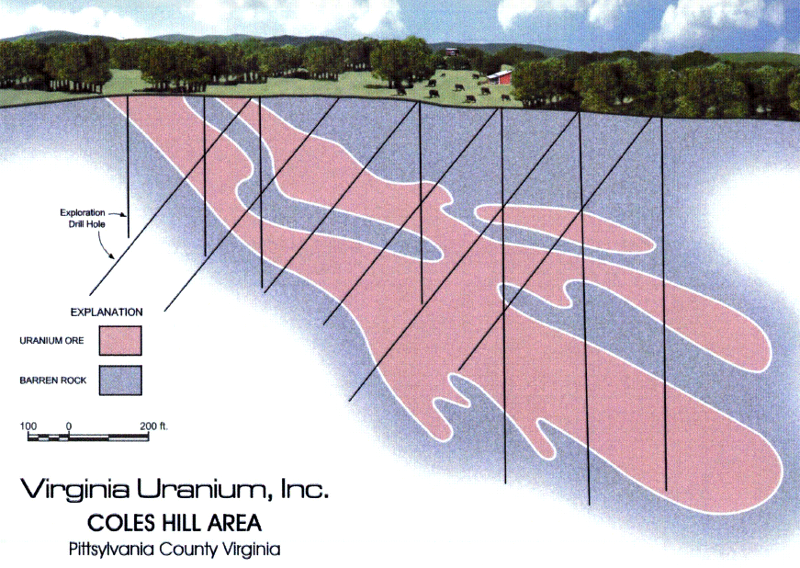

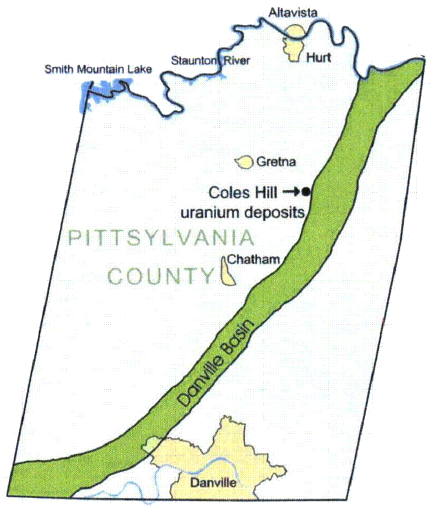

the largest unmined uranium deposit in North America is at Coles Hill in Pittsylvania County

Source: Virginia Uranium, Inc., Fuel for America, Jobs for Southside

the largest unmined uranium deposit in North America is at Coles Hill in Pittsylvania County

Source: Virginia Uranium, Inc., Fuel for America, Jobs for Southside

The uranium found now in Virginia was created when one or more supernovae exploded at least 4.5 billion years ago, or perhaps when two neutron stars collided near the site of our solar system. During such cataclysmic events, 92 protons were fused together in a natural particle accelerator to create uranium atoms. Those atoms were then blasted out into space. Gravity later brought some uranium atoms into the cloud that condensed to form the Earth and the rest of the Solar Systm 4.6 billion years ago.

the atoms of uranium now found on earth formed originally when stars exploded as supenovae or when neutron stars collided

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), The Clumpy and Lumpy Death of a Star and Neutron Stars Rip Each Other Apart to Form Black Hole

The heavy uranium initially sunk down into the mantle, but volcanoes redistributed some atoms on the surface. There is uranium almost everywhere at very low levels, but in a few places there is valuable ore where uranium is concentrated. The process of concentration is based on how tectonic forces squeezed and cracked various chunks of continental crust, and where fluids such as water helped uranium to migrate and to concentrate.

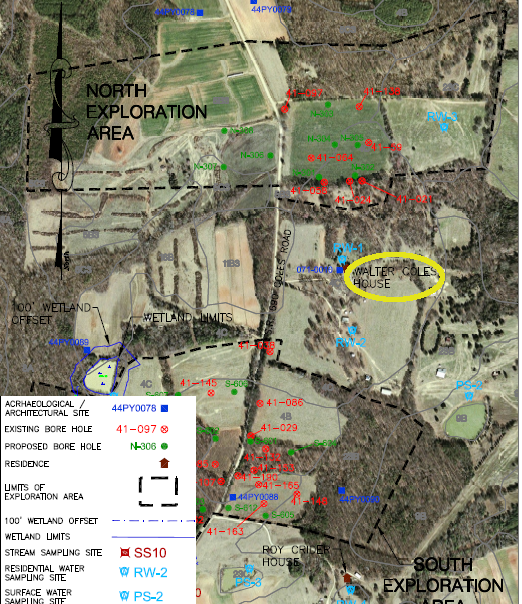

One of the major concentrations of uranium - and now a valuable mineral deposit - ended up in Pittsylvania County. The property on which it was discovered was first acquired by the Coles family in 1785, and the family plantation home (Coles Manor) was built soon after the War of 1812. The owner was Walter Coles V, a fifth-generation descendant of the original Walter Coles who had purchased 5,557 acres and began building the family fortune with slave labor.

In the early 1980's, after the "oil shocks" of the 1970's stimulated investments in other forms of energy, the Marline Uranium corporation searched for uranium in the Piedmont physiographic province of Virginia. The company discovered the Swanson ore deposit in Pittsylvania County, as well as other deposits that were less valuable. According to the Richmond Times-Dispatch1

The deposit at the Coles Hill site in Pittsylvania County has been described as:2

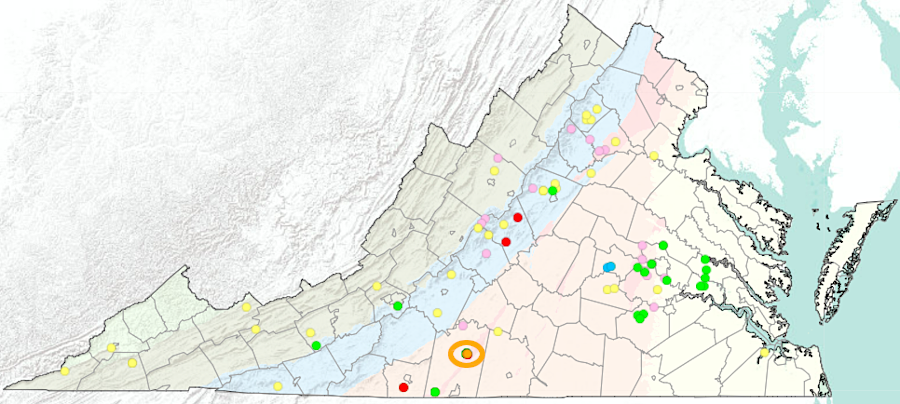

uranium has been identified in shale, metamorphic rocks, and sediments across Virginia, but only the Coles Hill deposit (orange circle) is commercially valuable

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Uranium Occurrences in Virginia

In 2011 Virginia Uranium Inc. estimated the deposit to be worth $7 billion. A separate 2011 report calculated the ore deposit included 119 million pounds of uranium, of which 63 million pounds exceeded 0.06% uranium and was economical to process. If uranium prices were $45-$75 per pound during the 35-year life of a mine, revenues would be $2.1-$3.5 billion.3

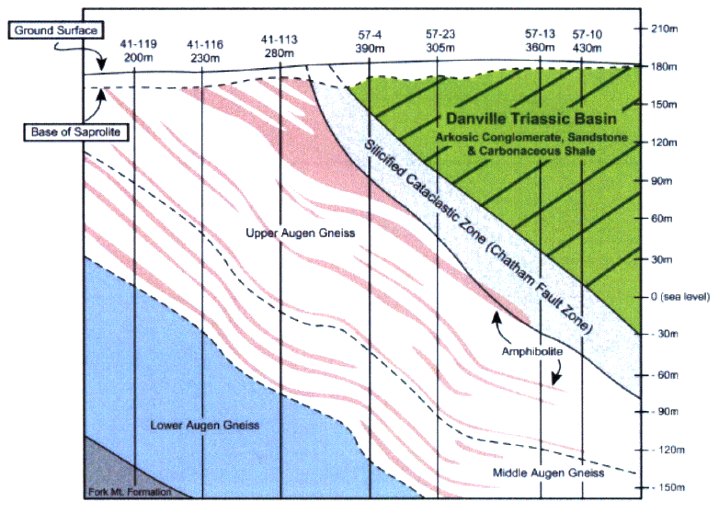

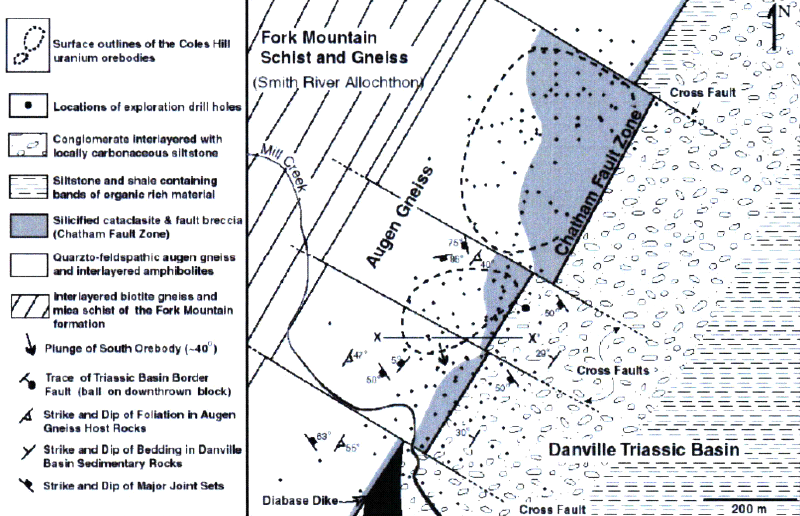

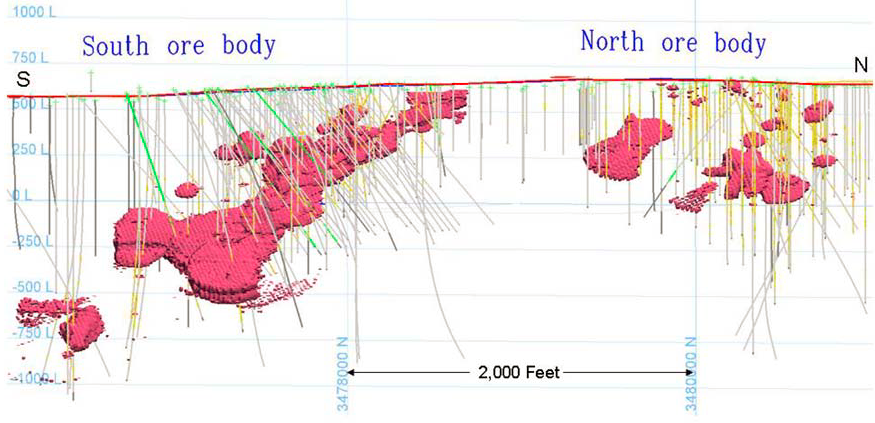

geology of Coles Hill uranium deposit

Source: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Technical Report on the Coles Hill Uranium Property

Pittsylvania County, Virginia

The estimated value of the deposit has changed dramatically over time. In the 1990's, Marline Uranium went out of business because there was not a sufficient demand for the ore.

Virginia had banned uranium mining in 1982, before projects planned in Orange and Pittsylvania counties went into operation. Efforts to lift the moratorium were not pursued vigorously after 1982. The price for yellowcake, the powdered uranium oxide ore (U3O8), remained too low to justify investment in new uranium mining operations. Marline Uranium donated the core samples it had drilled through the deposit to the Virginia Museum of Natural History, which has made the more than 7,000 boxes of rocks available to researchers.

Two decades later, economics changed. The landowner, Walter Coles, organized a new company with local neighbors and investors from Canada. Virginia Uranium, Inc. acquired rights to the deposit and began efforts to overturn the ban. The Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy approved a permit for exploring 194 acres in Pittsylvania County in November, 2007.4

uranium at Coles Hill is located just west of the Danville Basin

Source: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Technical Report on the Coles Hill Uranium Property Pittsylvania County, Virginia

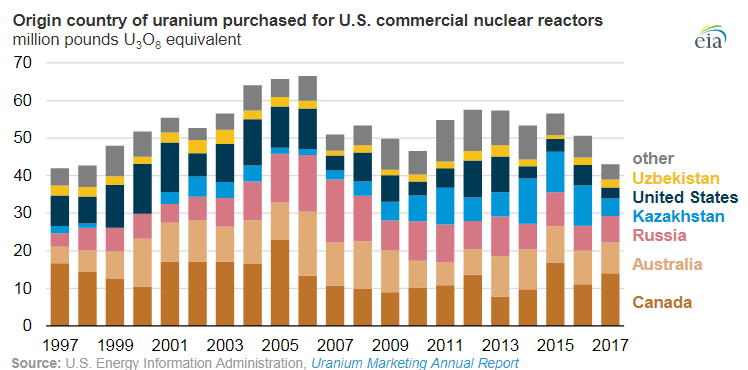

Virginia imports all of the uranium used in the reactors at Lake Anna and Surry, either from foreign countries or from mines west of the Mississippi River. Before arrival, the U-238 isotope in the yellowcake has been enriched with additional U-235 and converted to UO2. Virginia has no facilities that can convert yellowcake into uranium hexafluoride (UF6) gas, enrich it with additional U-235, and create the UO2 for fuel pellets.

For commercial nuclear reactors, pellets of the uranium have been fabricated into fuel assemblies, metal canisters which can be inserted into reactors. At the BWXT site in Lynchburg, some of the UO2 is examined and manipulated for military reactors. If the Pittsylvania ore deposit were developed, any nuclear fuel fabrication in Lynchburg would still have to import UO2 processed at an out-of-state facility.

Mining at Coles Hill could involve excavating a large open pit mine up to 850 feet deep, followed by crushing the ore and separating the uranium from waste rock. Virginia Uranium Inc. plans an underground mine, removing ore and creating rooms with pillars left to support the roof. After 21 years of such excavation, the pillars would be pulled during another 13 years of mining, and the rooms would collapse. Coal is mined underground in a similar process.5

Virginia Uranium Inc. animation on how a mine and mill at Coles Hill may look

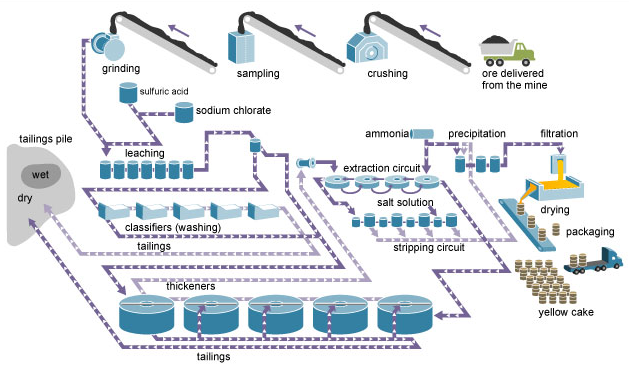

The 50 states - not the Federal government - regulate the actual mining operations for uranium, just like mining for coal, limestone, or other mineral resources. After uranium ore is removed from the ground, it must be "milled," or processed to separate the uranium from water rock.

Milling consists of grinding the ore, then soaking the powdered rock through highly-alkaline fluids to separate out the uranium. The final product at the mine site is "yellowcake," with ore concentrated to about 80% uranium oxide (U3O8).

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) is responsible for regulating milling operations, and issues Federal permits independent from the mining plans which are regulated by state agencies. Federal standards for milling must be met, but states are authorized to impose even stricter requirements.

If Virginia approved uranium mining as was considered in 2013, then the residue of waste rock from traditional open pit or underground mining and milling operations ("tailings") would be stored in above-ground cells on the property. When mined, 80-90% of the radiation in a uranium ore deposit ends up in the tailings piles.

Tailings piles on the surface can be designed like modern landfills with liners and clay caps that keep the waste isolated from rain and groundwater. Tailings could also be stored underground in cells within mined-out areas.

There are no open pit or underground uranium mines in the United States now.

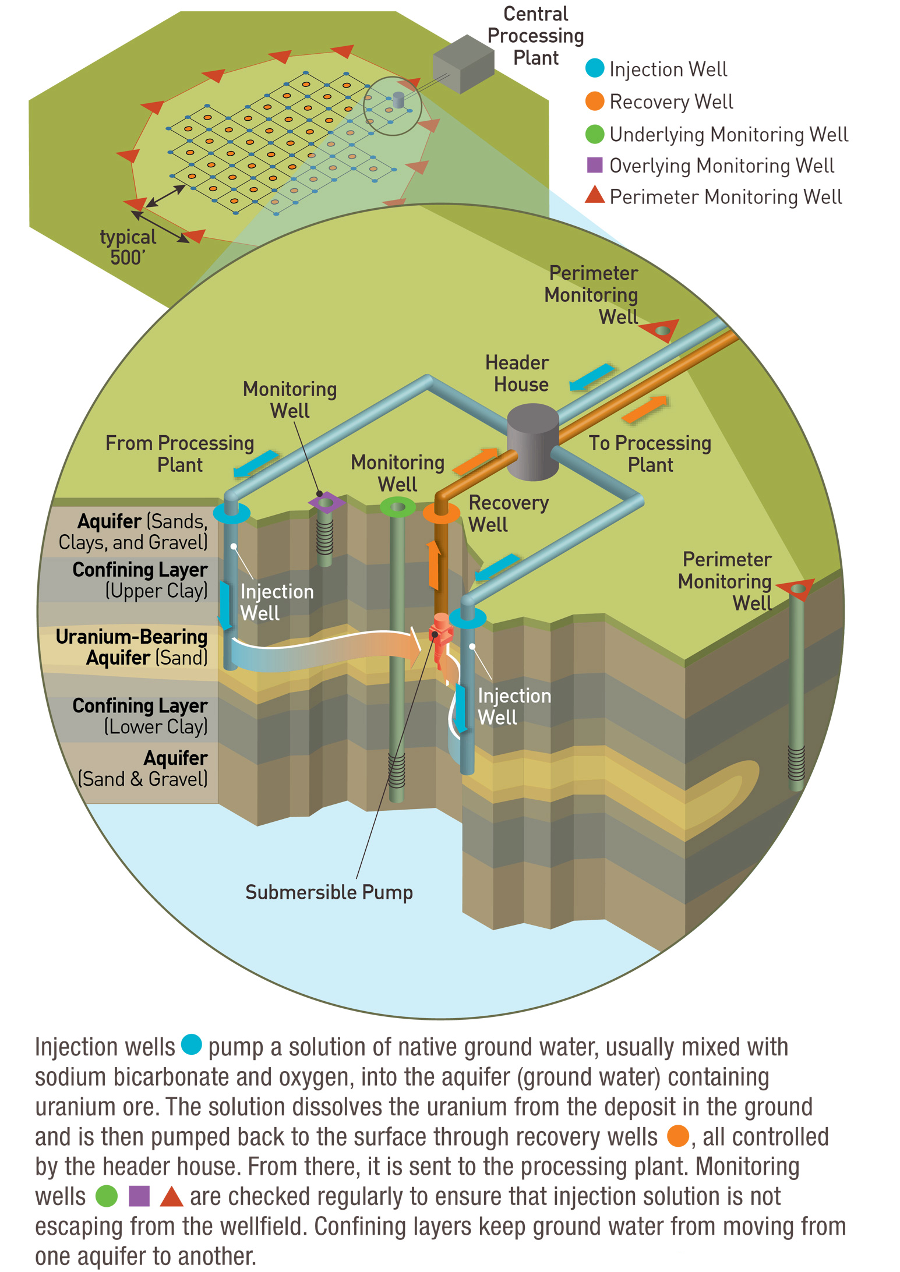

The alternative technique to an open pit or underground mine is in situ leaching, which minimizes the creation of tailings. Acidic fluids would be injected into the ore underground. The fluids would dissolve the uranium without excavating rock, other than the holes drilled for injection. The acidic liquids, "pregnant" with the dissolved uranium, would be pumped out of the ground. A facility on the surface would process the liquid to separate the valuable uranium and to recycle the acidic fluids.

While open pit and underground mines are regulated by state agencies, in-situ leaching is regulated by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Virginia Uranium Inc. did not pursue a Federal mining permit because the Coles Hill deposit is not suitable for in-situ leaching, however.6

extraction of uranium at Coles Hill by in-situ leaching would be regulated by a Federal rather than a state agency

Source: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, In Situ Recovery Facilities

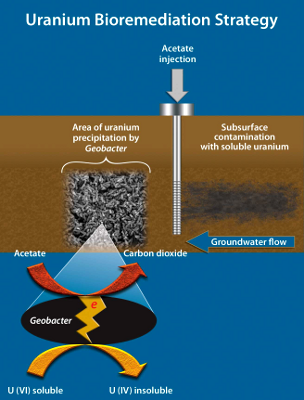

Because most uranium mines are in arid locations, opponents to the proposed uranium mines in Virginia highlight the potential risks of radioactive mining and mill wastes escaping the site through runoff or groundwater seepage. Uranium normally interacts with groundwater to form the uranyl ion, [UO2]2+ This ion is very stable and soluble. When dissolved, radioactive uranium can spread throughout an area and it is difficult to remove it, though bioremediation of contaminated groundwater by bacteria in the Geobacter genus may be possible.7

Under the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) set a limit of 30 micrograms/liter of uranium in drinking water. In 2004, two wells used for drinking water in Dinwiddie County, Virginia were found to have natural uranium levels either at or above the EPA recommended limit. A water treatment system was installed to reduce the concentration of uranium to below the EPA threshold.8

Naturally, the Coles Hill deposit is not demonstrating expected migration of uranium through groundwater. A. K. Sinha was quoted in a Virginia Tech news release:9

As noted in the 2001 PhD dissertation on the geochemistry of the Coles Hill site by James L. Jerden, the deposit is a closed system. Uranium ions dissolved near the surface are redeposited "below the water table due to higher pH conditions of ~6.0 and relatively high activity ratios of dissolved phosphate to carbonate," trapping the uranium at the site in a natural storage facility.10

Mining the deposit will require lowering the groundwater level, then extracting the ore by room-and-pillar excavation or by in-situ leaching. That could alter the current chemistry of the site, which traps the uranium and prevents it from migrating. In addition, the 44 inches/year of rainfall at the site could generate runoff that carries pollution downstream.

Geobacter might be injected underground with key nutrients, to precipitate uranium out of groundwater

Source: US Department of Energy, Genomics:GTL Roadmap (p. 219)

Though mining plans require mitigation to minimize impacts, an evaluation of plans vs. results at hard rock mining operations noted in a Halifax County Chamber of Commerce report that:11

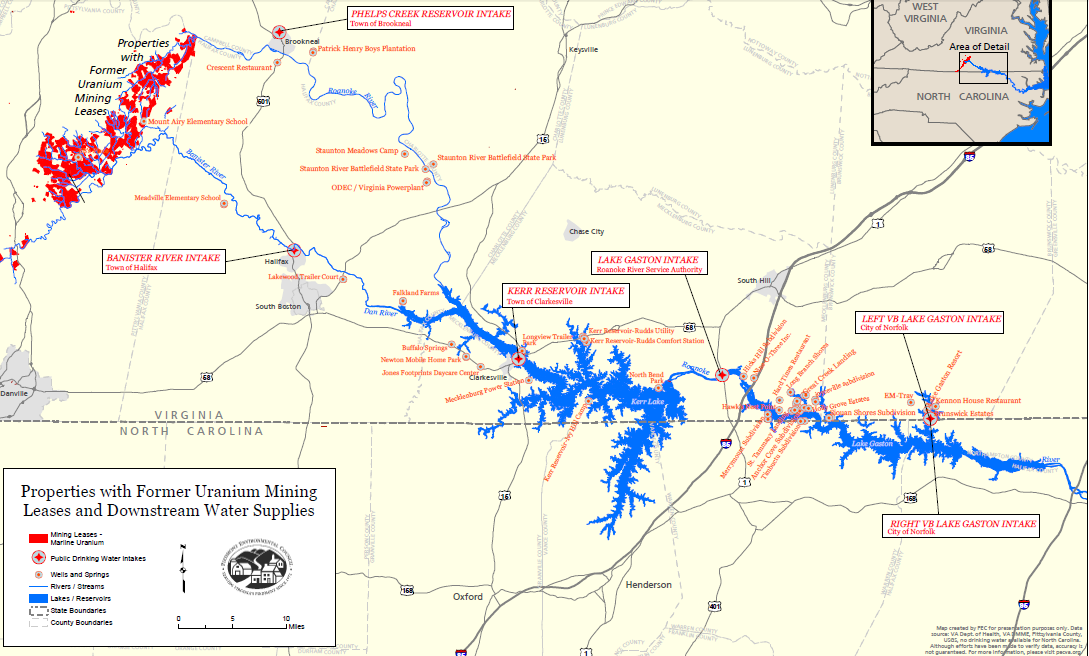

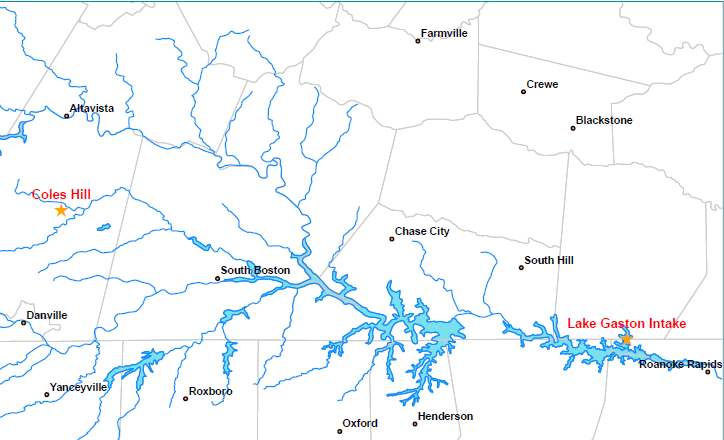

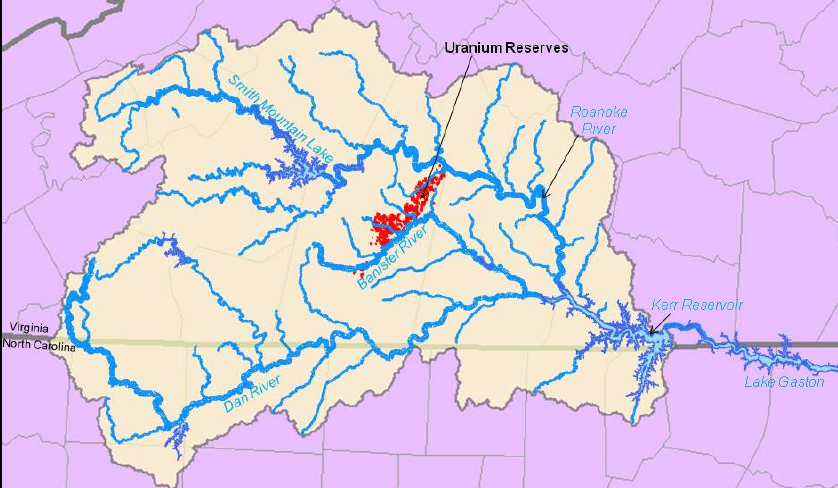

The Coles Hill Deposit in Pittsylvania County is northeast of Chatham, in the Mill Creek watershed. The creek drains into Bannister River, which flows into the Roanoke River. Ultimately, water draining off Coles Hill reaches the Albemarle-Pamlico Sound - after passing through Lake Gaston, a key part of the drinking water supply for the City of Virginia Beach. The city pumps water from Lake Gaston to Norfolk's water system, and treated water from Lake Gaston is then distributed to customers in the cities of Norfolk, Chesapeake, and Virginia Beach.

Virginia Beach officials have expressed opposition to the proposed uranium mining, fearing radioactive contamination of the city's water supply via Lake Gaston. If a severe, worst-case storm generated the maximum possible precipitation in Pittsylvania County (even more powerful than Hurricane Camille's impact on Nelson County in 1969 and a 1995 storm in Madison County), any above-ground containment cells at Coles Hill could break in a catastrophic release and uranium mining wastes could flow downstream. Flushing the excessive radioactivity out of the water supply might require as much as 2 years.12

uranium mining leases and downstream water system intakes

Source: Piedmont Environmental Council (PEC), map of former uranium mining leases in southern Virginia

In 2008, the General Assembly rejected a proposed study that could have led to a revision in the 1982 ban on uranium mining in Virginia, after one influential state delegate noted that his district gets some of its drinking water from downstream of the proposed mine. Virginia Beach is also downstream, because it draws water from Gaston Reservoir.

Virginia Beach water intake is downstream of Coles Hill

Source: Virginia Beach, Uranium Mining Impact Study presentation to Roanoke River Basin Bi-State Commission (25 July 2012)

Then the state's Coal and Energy Commission requested Virginia Tech's Virginia Center for Coal and Energy Research (VCCER) to partner with the National Academy of Sciences, and study "whether uranium mining, milling, and processing can be undertaken in a manner that safeguards the environment, natural and historic resources, agricultural lands, and the health and well-being" of Virginia citizens."13

Virginia Uranium Inc. (VUI) agreed to provide $1.4 million to fund the study, thus bypassing the General Assembly's failure to initiate a process that might overturn the ban on uranium mining. The National Academy does not accept full funding of studies from private companies with an economic interest in the result, to preserve the appearance of impartiality, so the VUI funding was given to the Virginia Center for Coal and Energy Research at Virginia Tech, and the university transferred the money to the National Academy.

The Uranium Mining Sub-Committee of the Coal and Energy Commission also obtained a socioeconomic study of the potential impacts of mining the Coles Hill deposit, particularly regarding employment in the "labor shed" around Chatham (including Pittsylvania County, Danville City, Campbell County, Halifax County, Henry County, Martinsville City, Franklin County, Bedford County, and Bedford City). The study, by Chmura Economics & Analytics, reported in November, 2011 that:14

Opponents of mining the Coles Hill deposit have highlighted the potential water quality impacts. Because local groundwater levels are so high, opponents predict that plans for underground mining ultimately will be rejected, Coles Hill ore will be extracted via an open pit mine, and retaining ponds at the surface will be exposed to storms dropping as much as 30 inches of rain. Even with surface mining, opponents predict that groundwater could be contaminated with chemical and radioactive wastes during the mining process, and for centuries afterwards as the sulfur minerals in the "tailings" gradually changes local pH.

Walter Coles, owner of the uranium deposit, has a house located between the northern and southern deposits proposed for mining

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Figure 5 - Aerial Photography-Exploration Permit Map

(archived version of DMME's web page for "Uranium Exploration Permit Approved")

A November, 2011 report prepared for the Roanoke River Basin Association stated:15

open pit uranium mine

(Midnight Mine in Washington State)

Source: Environmental Protection Agency, Superfund's 30th Anniversary

The December, 2011 report from the National Academy of Sciences noted that there would be "steep hurdles" to overcome before lifting the 1982 ban on uranium mining, but the report was not designed to recommend/not recommend whether to permit development of the Coles Hill deposit. That policy decision is a judgment call, not a scientific conclusion, and will be made by the elected officials in the state General Assembly. Some of the conclusions from the National Academy report were:16

The National Academy summarized its conclusions:

The immediate response from Virginia Uranium, Inc. was to issue a news release titled "National Academy of Sciences Study Provides 'Road Map' for Virginia to Host Safest Uranium Mine in the World" and to press the 2012 General Assembly to lift the moratorium. However, the Richmond Times-Dispatch, traditionally friendly to private sector business initiatives and opposed to government regulation, reacted in an editorial titled "Uranium Mining: Make haste slowly" that:17

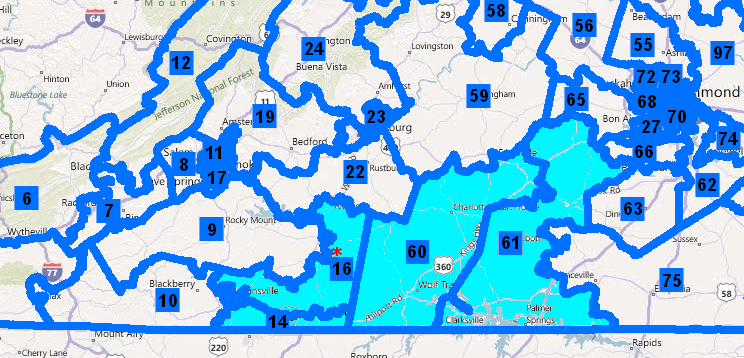

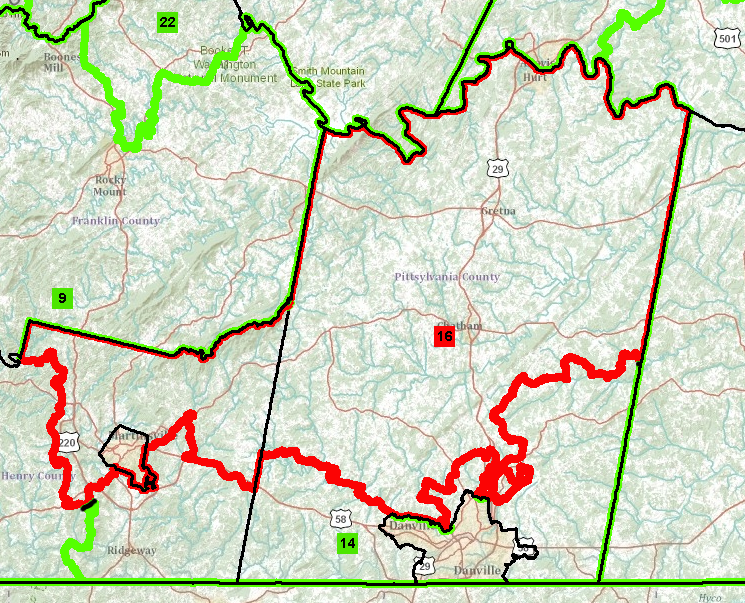

Four Republican members of the House of Delegates and the State Senator from the 19th District (including the Coles Hill site) made a similar call for caution and delay, before the opening of the 2012 session of the General Assembly (scheduled to meet for two months between January-March, 2012). Rep. Donald Merricks of the 16th District, the House District where the uranium deposit is located, said:18

districts of House of Delegates members calling for delay until 2013 before considering lifting the ban on uranium mining

include Coles Hill (red asterisk) and all downstream areas

Source: Virginia Division of Legislative Services, Redistricting 2010

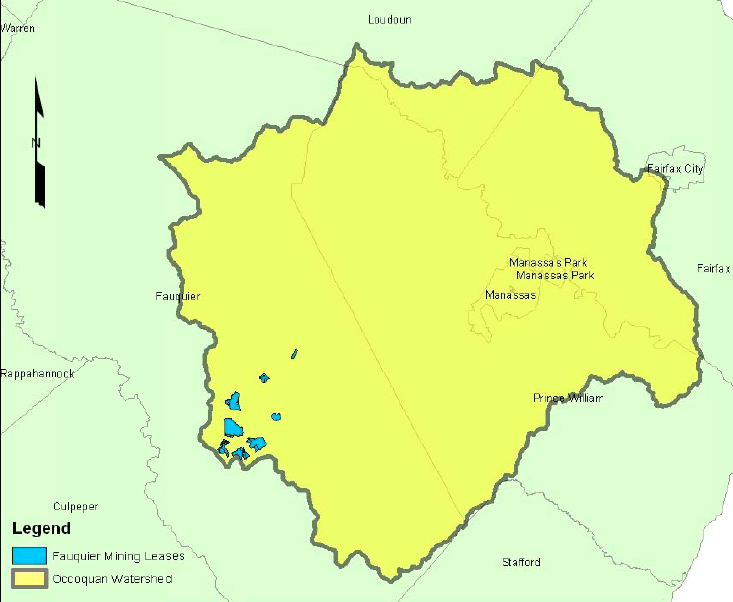

Since the General Assembly includes members from regions other than Southside Virginia, advocates on both sides of the uranium mining issue have been lobbying legislators from all parts of the state. The Piedmont Environmental Council highlighted theoretical threats to the water supply in the Piedmont and Northern Virginia, alerting legislators from those areas that the uranium mining issue was not limited to just Pittsylvania County or the Roanoke River watershed.

At the end of 2011, Fairfax Water commissioned a study to document how the Occoquan Reservoir could be contaminated, if former 1982 leases in Fauquier County were renewed and developed. The report noted:19

The report determined that in the worst-case scenario of a catastrophic failure of a tailings impoundment, the Fairfax Water filtering processes could concentrate radioactive materials to excessively high levels, and increase the cost of operations. One recommended solution was to ban uranium mills and tailing impoundments from the Occoquan River watershed, presumably shifting those operations to the Rappahannock River watershed - which supplies most of the drinking water for the City of Fredericksburg.

1982 uranium mining leases in Fauquier County, upstream of Lake Manassas and Occoquan Reservoir

Source: Fairfax Water

Virginia Beach enlisted support from other communities by highlighting risks to their water supply. If a tailings pond failed at Coles Hill:20

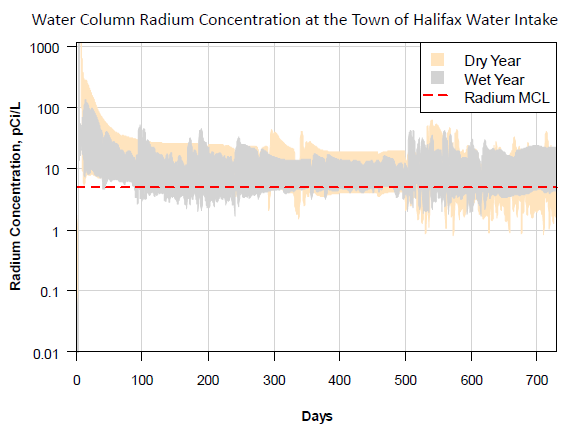

However, if a radioactive tailings pile broke during a storm event, the Town of Halifax would be affected for years. Its water supply from the Bannister River would exceed the Maximum Contaminant Levels (as defined in the Safe Drinking Water Act) for radium. By highlighting such concerns, Virginia Beach pressured Virginia Uranium into committing to store all tailings below ground level.21

Virginia Beach found allies in Halifax and Pittsylvania counties by highlighting risks of a major storm triggering a release of radioactive material

Source: Virginia Beach, Uranium Mining Impact Study presentation to Roanoke River Basin Bi-State Commission (25 July 2012)

In September, 2012 the economic benefits to local residents in Pittsylvania County were documented in a best-case analysis by George Mason University's Center for Regional Analysis. The assumptions of the analysis helped shape the conclusions:22

The report quantified the tax benefits to Pittsylvania County property owners. In the ideal circumstances, residents would see a 7-8% reduction in property tax rates, from $0.52 per $100 of property value to a $0.48 tax rate.

The region has been hard hit by the decline in manufacturing and lower demand for tobacco. In the 1990's, state and local officials planned for revitalization of the area, long before the Coles Hill deposit was revealed.

Plans to grow the local economy are based largely on investments funded by the 1998 Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, recycling tobacco-based money to trigger new jobs based on high-tech manufacturing. Also significant are grants from the Danville Regional Foundation, funded from the sale of the Danville Regional Hospital.

Grants have helped fund a fiber-optic network (Mid-Atlantic Broadband Cooperative), providing high-speed Internet connectivity to schools and businesses to facilitate distance learning and recruit knowledge-based businesses. Virginia Tech has located advanced research facilities in Danville, launching the Institute for Advanced Learning and Research together with Averett University and Danville Community College. General Motors has located the National Tire Research Center at the local NASCAR race track, Virginia International Raceway.

Despite the potential jobs and economic benefits from the Coles Hill project, some key local business leaders remain opposed to uranium mining. In 2011, the town councils of South Boston and Halifax, along with the Halifax County Supervisors, officially voted against lifting the ban on uranium mining in Virginia. In September, 2012, the Halifax County Chamber of Commerce also supported maintaining the moratorium.

Business leaders in Halifax County, adjacent to Pittsylvania County where the Coles Hill deposit was located, feared the potential negative stigma to agriculture and tourism from short-term impacts of mining radioactive material and long-term storage of tailings. The Pittsylvania County supervisors split, and in 2012 declined to support the ban.23

Coles Hill uranium deposit is located in Pittsylvania County, just west of Halifax County and adjacent to the City of Danville

Source: Bureau of Census

According to one local business leader, the local economic recovery plan is working without a stimulus from mining. Uranium could threaten the long-term economic vitality of the area, ruining its reputation as an environmentally clean area for production agriculture and a safe area for locating a business. In addition, Pittsylvania County receives major benefits from two private schools, Hargrave Military Academy and Chatham Hall.

Even if an underground mine included underground storage of the tailings to minimize the potential release of waste into the Bannister River, the association of the area with radioactivity could poison efforts to attract tourists, spur sales of locally-produced agricultural products, and increase attendance at local private schools. A local business leader, the former chair of the Virginia Chamber of Commerce, noted:24

The Pittsylvania County Board of Supervisors split on the issue. In November, 2012, the supervisors voted on a motion that proposed "block mining" language:25

The board rejected the language a 4-3 vote, suggesting that the local officials may end up supporting a mining operation. The local state senator, who has said he opposes mining, also suggested that General Assembly action lifting the moratorium could include a provision that Pittsylvania County might be granted the local option to veto development of the site.26

At the end of November, 2012, the Hargrave Military Academy president and trustees went on record as opposing the proposed mine. More significantly, before the Uranium Working Group made any recommendation to the Virginia Coal and Energy Commission the politically powerful Virginia Farm Bureau publicly opposed lifting the ban. As expressed by the Farm Bureau:27

At the state level, the Farm Bureau was opposed to mining the Coles Hill deposit but the Pittsylvania chapter was split on the issue. Some local farmers saw the potential of increasing local jobs, and were concerned about government authorities limiting how land could be used. On the other hand, some farmers feared mining would lower the value of their dairy farms if customers were reluctant to buy milk from an area known for its radioactivity. One opponent noted:28

rivers and uranium deposits in Pittsylvania County

Source: White Paper: Uranium Mining in Virginia (March, 2010 report by Michael Baker Jr. Engineers, Inc. to City of Virginia Beach)

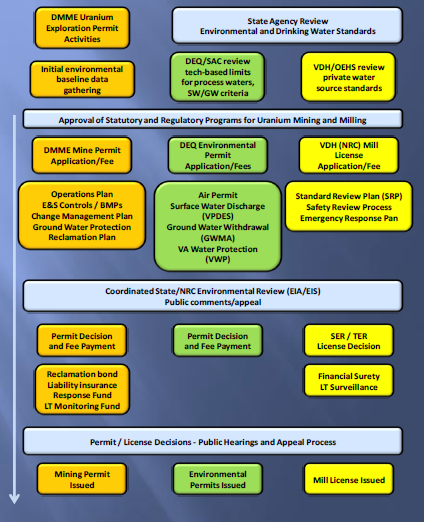

To address specific concerns, Gov. McDonnell created a Uranium Working Group in 2012 with representatives from Virginia Department of Health, Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, and the Department on Environmental Quality. That group spent most of 2012 developing a conceptual regulatory framework for mining the Coles Hill deposit.

If implemented, state regulation could cost $5 million/year, presumably paid by fees that would be imposed on the uranium mine.29

The Final Report, issued at the end of November, 2012, addressed most of the 18 issues posed by the governor when the group was created. For example, it identified the possibility of establishing a groundwater management area, since dewatering the site will be required for underground room-and-pillar mining.

The report also noted that Virginia had responsibility for issuing a mining license, but the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has responsibility for any milling operation - though Virginia could become an "Agreement State" and assume the lead role. Development of the Coles Hill deposit will require a full Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), if the ore will be milled at the site rather than shipped to a separate location for that processing.30

conceptual statutory and regulatory framework for mining uranium in Virginia

Source: Uranium Working Group, Final Report (Figure 3)

As Gov. McDonnell noted when the report was issued, assessment of potential socioeconomic impacts was delayed:31

The member of the Virginia House of Delegates for the district that includes Cole Hill, Delegate Don Merricks (R-16th District), campaigned for that office in 2007 on his business-oriented background:32

Nonetheless, after the release of the Uranium Working Group's Final Report in 2012, Del Merricks expressed his opposition to mining the deposit:33

boundaries of 16th District (including Coles Hill), represented by Delegate Donald Merricks in Virginia House of Delegates

Source: Virginia Division of Legislative Services, Redistricting 2010

In December, 2012, the Danville Pittsylvania County Chamber of Commerce finally expressed clear opposition to mining the uranium deposit. The Lieutenant Governor, Bill Bolling, also joined the local business leaders and Del. Merricks in opposition. The Lieutenant Governor, who had been designated the "chief jobs officer" for the administration of Gov. Bob McDonnell, also highlighted economic arguments as the primary reason for his opposition:34

In January 2013, just before the General Assembly met, the Danville City Council passed a resolution unanimously supporting the moratorium. Local opposition to the project, from communities that were projected to receive some economic benefits, greatly complicated efforts by mining advocates to alter the state's ban. Key members of the General Assembly still pushed forward as the January, 2013 session started.35

In 2013, the Virginia Commission on Coal and Energy officially voted in favor of lifting the ban in an 11-2 vote. Del. Donald Merricks (R-16th District), representing Coles Hill, voted in opposition. The Democratic Minority Leader of the State Senate, Dick Saslaw, expressed strong support for mining. He advocated that the economic benefits trumped any potential risks from long-term management of radioactive waste:36

The former mayor of the town of Hurt, on the Roanoke River but upstream of the area that might be affected by a release of waste, highlighted two key reasons why she supported mining uranium despite claims that the area might be stigmatized:37

one ton of mined uranium ore is typically processed into one-four pounds of yellowcake (U3O8), so over 99% of the mined rock ends up as tailings

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Where Our Uranium Comes From

At the start of the 2013 session of the General Assembly, the clerk of the State Senate referred the bill to lift the uranium ban (SB 1353) to the Agriculture, Conservation and Natural Resources Committee, which traditionally debates mining issues. The bill's sponsor, State Senator John Watkins (R-Powhatan), had hoped for a referral to the Commerce and Labor Committee. He chaired that committee, increasing the possibility that the State Senate could end up endorsing mining the uranium in the Coles Hill deposit.

The referral decision may have been key to the final resolution in the legislature, because a majority of the Agriculture and Natural Resources Committee indicated opposition. Sen. Watkins withdrew the bill at the end of January, 2013 without any formal vote.38

The 2013 General Assembly did create a nonstock, nonprofit corporation called the Virginia Nuclear Energy Consortium, and directed it to make Virginia a "national and global leader in nuclear energy." The consortium will be funded through whatever grants it can obtain, and governed by a 17-member board that includes state and Federal officials, Virginia universities, and Virginia businesses related to the nuclear energy industry such as Areva, Babcock & Wilcox, and Dominion Virginia Power.

Groups that opposed uranium mining in Virginia had opposed the legislation, fearing it would create a new mechanism for ultimately permitting development of the deposit at Coles Hill.39

In November 2013, right after being elected governor, Terry McAuliffe used a meeting in Norfolk to announce that he would veto any legislation that authorized uranium mining. A month later, Virginia Uranium Inc. cited the bluntness of the governor-elect's statement when it announced the company would suspend efforts to obtain General Assembly approval for extracting the uranium at Coles Hill. At the same time, the long-term price of uranium dropped to $50/pound, below the anticipated $64/pound value used to predict the return on investment in developing the deposit.40

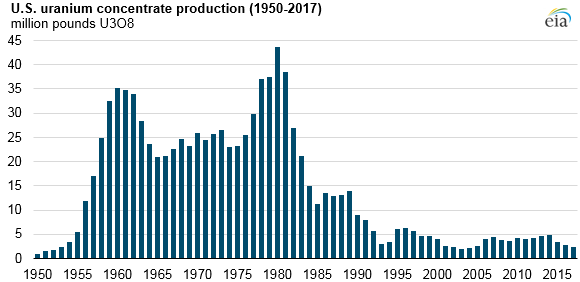

domestic production of uranium concentrate peaked at 43.7 million pounds in 1980, but has remained lower than 5 million pounds annually since 1997

Source: US Energy Information Administration, U.S. uranium production in 2017 was the lowest since 2004 (February 26, 2018)

Between 2008-2018, the number of employees for uranium exploration dropped 94%, from 457 full-time equivalent employees to only 27, because there was little demand for finding new sources of the fuel. Despite persistent low demand, one local opponent has noted that uranium was still a valuable deposit and predicted the mining issue would reappear:41

a surface mine at Coles Hill might resemble Midnight Mine, a former uranium mine in the Selkirk Mountains of eastern Washington State

Source: Environmental Protection Agency, Uranium Mines and Mills

After Governor McAuliffe made clear his opposition to mining the Coles Hill deposit, Virginia Uranium Inc. shifted its focus from the legislature to the courts. One lawsuit in a Federal court (U.S. District Court for the Western District of Virginia in Danville) was dismissed. The company then moved to the state court system and filed a second suit in the Wise Circuit Court.

That state lawsuit claimed the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission was responsible for crafting uranium mining regulations, and that Virginia could not block such development. Virginia Uranium Inc. also claimed that the state's action to block mining was equivalent to seizing property, and the company was entitled to compensation. The state claimed the ban was based on the state's legitimate authority to protect public health and safety.

The state response included an economic assessment of the Coles Hill deposit's value. The state lawyer noted that in 2016 uranium ore (yellowcake) was selling at $18.65/pound, while:42

in 2018, domestic mines supplied just only 10% of the uranium used in commercial nuclear reactors within the United States

Source: US Energy Information Administration, In 2018, foreign-sourced uranium accounted for 90% of U.S. nuclear operators' purchases

The state court suspended action. In Federal courts, the state won in Circuit Court and with a 2-1 decision at the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, with rulings that the state of Virginia had the authority to ban uranium mining. Virginia Uranium Inc. appealed to the US Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case (Virginia Uranium Inc. v. Warren).

The U.S. solicitor general filed a brief siding with Virginia Uranium Inc. They contended that the Federal government's authority, granted by Congress in the 1954 Atomic Energy Act, preempted Virginia's ability to ban uranium mining based on state concerns. "States rights" were superseded by the authority of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Virginia argued that the authority of that Federal agency, as defined under the Atomic Energy Act, was limited to Federal lands. Since the Coles Hill deposit was on private lands, the state could regulate and even ban mining.43

As the US Supreme Court prepared to hear the appeal, Pittsylvania County officials made clear their opposition to mining the Coles Hill deposit. When the president of Virginia Uranium requested in 2018 that 24 acres be rezoned from residential to agricultural, so the land would qualify for a lower property tax rate. The county Planning Commission unanimously rejected the request, reflecting its concerns tat the land might become part of a future mining operation.

The State Senator, William Stanley Jr. noted:44

The court case drew national attention, in part because it flipped the standard perceptions of advocacy. Organizations that normally supported loosening Federal regulations to enhance a business-friendly environment had to make a choice. To create the opportunity to mine the uranium, Virginia Uranium Inc. argued that Federal judges should re-interpret the Atomic Energy Act and trump the right of a state to control mining of uranium. By increasing Federal authority, pro-mining advocates argued that a private company would have greater flexibility to do business.

Bloomberg titled its article about the case "A Virginia Farmer Fights to Harvest His Uranium."45

The final 6-3 decision by the US Supreme Court in June, 2019 upheld Virginia's authority to ban uranium mining.46

Resolving that case allowed Virginia Uranium to restart its 2015 lawsuit in state court. The company claimed the state's ban on uranium mining was a "taking" of private property. Virginia Uranium had missed a filing deadline in its legal actions, so it could not force the state to pay compensation even if the company convinced the court that all reasonable use of its land had been eliminated by the mining ban. However, a court victory might enable proceeding with actual uranium mining.47

The Wise County and City of Norton Circuit Court upheld the state's authority to ban uranium mining in July, 2020. The Supreme Court of Virginia declined to hear an appeal of the judge's decision.

The judge ruled that the ban on mining uranium was not an unconstitutional "taking" of private property even though the mineral estate, valued at least $427 million, would be "exponentially reduced" by the ban. The judge concluded:48

In 2022, newly-elected Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin released an updated State Energy Plan that called for construction of a Small Modular Reactor in Southwest Virginia. His support for nuclear power, along with discovery of a commercial quantity of gold in Buckingham County and the potential to update state regulations to allow opening a new gold mine, created new interest in the 3,000-acre Coles Hill deposit.

A Canadian firm, Consolidated Uranium Inc., purchased the site for $32 million. The company had been purchasing other closed uranium mines in Utah and Colorado, and generated no revenue from any operating facilities. Shareholders financed the acquisition with an expectation that Coles Hill and other sites could be developed as new technologies allowed for construction of new nuclear power plants:49

Desire for carbon-free electricity to reduce climate change, the need for new generation of electricity to power data centers, and the anticipated implementation of small modular reactor technology led to a predicted expansion in the need for uranium. According to the International Atomic Energy Agency, if demand grew worldwide to 100,000 tons of uranium per year by 2040 then existing and new mining operations would need to double output from 2024 levels.50

extent and depth of the uranium deposit at Coles Hill was determined by drilling boreholes and assessing samples of ore brought to surface

Source: US Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 05/01/2008 - Meeting Presentation Slides for Virginia Uranium, Inc., Coles Hill Deposit

vertical cross-section of Coles Hill deposits, looking west (0.1 wt% U3O8 )

Source: Virginia Uranium, Inc., Fuel for America, Jobs for Southside presentation

location of Coles Hill uranium deposit in Pittsylvania County

Source: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Technical Report on the Coles Hill Uranium Property

Pittsylvania County, Virginia