both low-level and high-level radioactive waste (in lead-lined casks) can be transported by rail

Source: US Department of Energy, West Valley Demonstration Project - Waste Management and Integrated Waste Management

both low-level and high-level radioactive waste (in lead-lined casks) can be transported by rail

Source: US Department of Energy, West Valley Demonstration Project - Waste Management and Integrated Waste Management

Radioactive materials are shipped routinely to medical centers and other places. The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration in the US Department of Transportation advises cargo handlers:1

Under the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission issues licenses for possession of radioactive materials. Under the Hazardous Materials Transportation Act of 1974, the US Department of Transportation is responsible for transportation of hazardous materials. To simplify Federal oversight, the two agencies have produced common guidance, and each has transferred key responsibilities in Virginia to state agencies.

The Virginia Department of Health licenses the possession of radioactive materials. Shippers who transport hazardous radioactive materials must register with the Virginia Department of Emergency Management, certifying that all shipments will be properly classified, described, packaged, marked and labeled.

Unused, fresh nuclear fuel is not classified as a hazardous material, so the Virginia Department of Emergency Management does not track shipments of low-enriched uranium going to Lynchburg for fabrication of fuel assemblies for US Navy ship reactors. Fresh fuel assemblies transported to the nuclear power plants at Surry and North Anna are not considered to be hazardous waste; they become "waste" only after being irradiated in the reactor.2

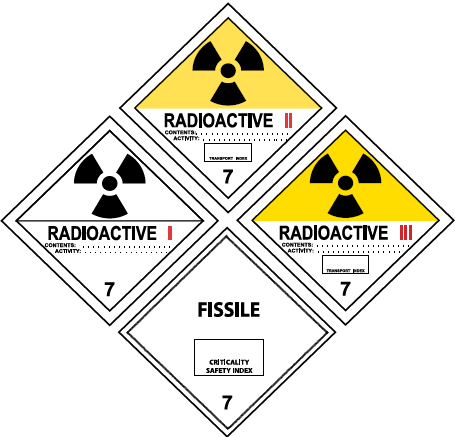

Low-level radioactive wastes are treated as hazardous materials in transport, with special signage for use on packages, trucks, and rail cars.

the RADIOACTIVE WHITE-I label means practically no radiation outside the package, RADIOACTIVE YELLOW-II label means some radiation outside the package, RADIOACTIVE YELLOW-III label is for higher radiation levels, and FISSILE white label indicates special handling instructions

Source: US Department of Energy, How to Handle Radioactive Materials Packages: A Guide for Cargo Handlers

In the Low-Level Radioactive Waste Policy Act of 1980, the US Congress directed states to establish regional compacts and agree among themselves where to locate facilities to store low-level radioactive waste. The residue from cancer treatments and X-rays at medical facilities is hazardous, but the risk can be contained through careful packaging and handling of waste materials and burial in a landfill. Unlike high-level radioactive waste created at power plants or transuranic waste created during production of nuclear weapons, low-level radioactive waste does not require disposal in a geologic repository such as a salt bed, volcanic tuff, or a deep borehole drilled into crystalline bedrock.

From Virginia, low-level radioactive waste is hauled to Clive, Utah or Andrews, Texas by rail and by truck on the interstate highways.

High-level radioactive waste is shipped across Virginia via CSX and Norfolk Southern tracks from Newport News, transporting used fuel assemblies from US Navy aircraft carriers. The reactors in those carriers must be refueled on a regular basis. The spent fuel assemblies are removed, placed in specially-designed casks made of 10" thick solid stainless steel, then transported to the Naval Reactors Facility at the Department of Energy's Idaho National Laboratory.3

M-290 Naval Spent Fuel Shipping Container is one cask design used to transport high-level radioactive waste from Newport News

Source: US Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board, Naval Spent Fuel Transportation

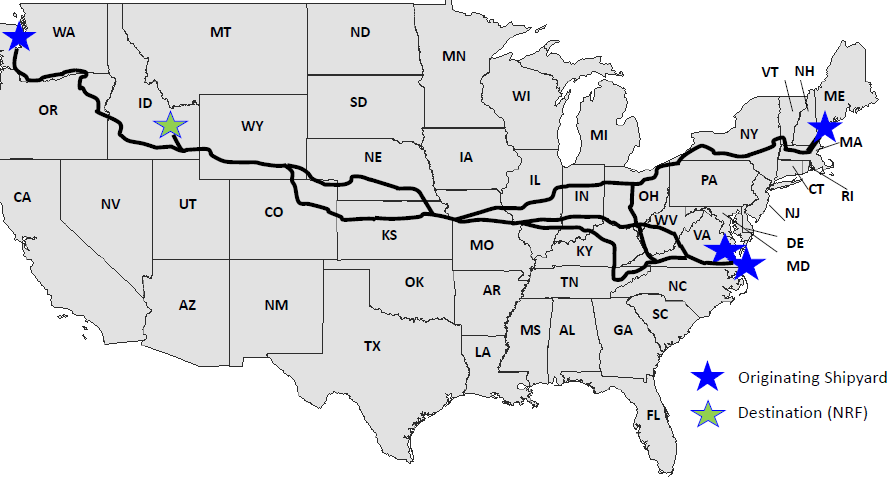

high-level nuclear waste from refueled aircraft carrier reactors goes by train from Hampton Roads to Idaho

Source: US Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board, Naval Spent Fuel Transportation

Train shipments of high-level radioactive waste would increase, if the Federal ever creates a repository for disposal of used fuel assemblies removed from reactors at the Surry and North Anna nuclear power plants. The US Congress passed the Nuclear Waste Policy Act in 1982, and then decided in 1988 to eliminate plans for a permanent geologic repository east of the Mississippi River. Those Federal actions established that the high-level radioactive waste produced at Dominion Virginia Power's two nuclear power plants would be transported out of state to a permanent repository west of the Mississippi River.

how high-level radioactive waste might have traveled to Nevada from Virginia, if Yucca Mountain had been completed as a permanent repository

Source: Nevada Agency for Nuclear Projects, Nuclear Waste Transportation Routes (1995)

Whenever a repository is created, Dominion Virginia Power will remove used fuel assemblies from the wet pools, placed the high-level nuclear waste in a cask for transport, and ship casks by rail, barge, and/or truck to whatever permanent location has been chosen by the Federal government.

High-level radioactive waste has been transported through Virginia. In 1985 and 1986, 69 used fuel assemblies were sent from the Surry Nuclear Power Plant to Idaho in 23 shipments to test three different types of dry storage casks. Until 1988, high-level wastes from foreign research reactors were shipped through Portsmouth, Virginia to Federal storage facilities at the Savannah River Plant in South Carolina.4

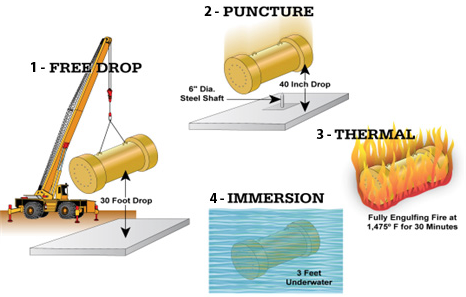

casks for transport of high-level radioactive waste are designed to withstand shock, fire, and water

Source: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Testing Spent Fuel Transport Casks Using Scale Models

Virginia could have hosted a permanent repository and three locations were examined, but plans for storing high-level nuclear waste east of the Mississippi River were dropped by the Reagan Administration. In 1987, the US Congress designated Yucca Mountain as the one permanent storage location for high-level nuclear waste produced by civilian reactors. That meant the spent fuel assemblies from Surry and North Anna would be transported on a regular basis from Virginia to Nevada.

Planned truck/rail routes for transporting nuclear waste from Virginia nuclear power plants to Yucca Mountain, Nevada

Source: Environmental Working Group (extract from the

Environmental Impact Statement for the repository at Yucca Mountain)

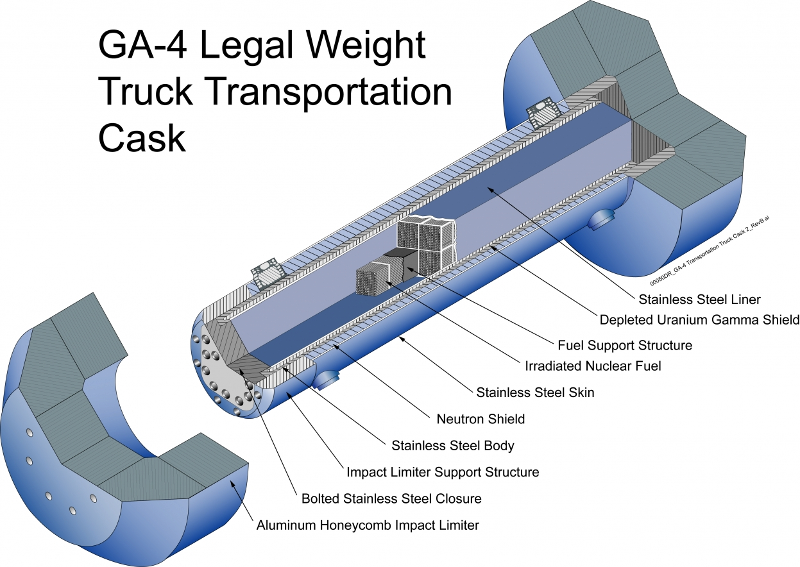

The preferred transportation process involves placing waste in special casks designed to withstand accidents or terrorist attack, then shipping the casks on rail cars to Yucca Mountain.

A railroad line built to the North Anna plant for its construction has been kept in operation, but there is no rail connection to the Surry plant. Casks of nuclear waste from Surry have to be shipped by truck, or by barge on the James River to the rail line in Portsmouth for transport to a final destination. In 1986, 60 fuel assemblies were transported from Surry by truck to the Idaho National Engineering Laboratory.5

Planned barge routes for transporting nuclear waste from Virginia to Nevada

Source: Environmental Working Group

Acceptance of nuclear waste at Yucca Mountain was delayed beyond the scheduled 1998 date, and Dominion Virginia Power was the first utility in the nation to begin moving spent fuel assemblies from wet pools into dry storage casks. The 115-ton casks have been placed on outdoor concrete pads at Surry and North Anna, in anticipation of future transport to a permanent repository. By 2016, Dominion Virginia Power had stockpiled 2,760 metric tons of high-level radioactive waste at those two locations.6

nuclear waste can be encased in concrete casks for shipment by truck

Source: Department of Energy, Energy Department Completes Cleanup of Legacy Waste

In 2010 the Obama Administration determined not to open the repository. By then, there was more than 70,000 metric tons of waste stored at power plants across the country, exceeding the initial capacity planned at Yucca Mountain. The Energy Department calculated that moving the backlog of high-level nuclear waste would require 24 years, assuming the repository could handle 175 train shipments annually - basically, one trainload, every other day.7

Casks have been specially designed for transport of high-level radioactive waste, and include impact limiters designed to act like bumpers if a cask is involved in a crash. Casks must be able to survive a 30-foot drop, a puncture test involving a 40-inch drop onto a 6-inch diameter steel cylinder, a 1,475°F fire for 30 minutes, and immersion under 3 feet of water.

There has been one truck accident, where the vehicle overturned and the cask came off the trailer. The truck driver died in the 1971 accident in Tennessee, but the cask remained intact. It successfully prevented any release of radiation, and was refurbished for reuse after the single fuel rod inside was removed as planned at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

in the one accident during transport, the cask successfully blocked the release of any radiation

Source: US Department of Energy, A Historical Review of the Safe Transport of Spent Nuclear Fuel (Figure 4-3)

In 2020 the US Department of Energy stated:8

casks carrying high-level radioactive waste must survive stresses of an accident during transport

Source: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Spent Fuel Transportation Risk Assessment- Final Report

The earliest versions were designed for fuel assemblies that were removed from reactors after a relatively short time. New procedures allow utilities to leave fuel assemblies in reactors for longer periods of time, extracting more energy from the uranium dioxide fuel but creating more fission products.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission has determined that dry storage casks can withstand the higher temperatures and radioactivity, ensuring that "high burnup" as well as older "low burnup" fuel assemblies can be transported to whatever location is ultimately chosen for a national repository.9

rail cars are expected to carry high-level radioactive waste from Virginia's two nuclear power plants to a permanent repository

Source: Department of Energy, Yucca Mountain

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission concluded in 2014 that there was a one-in-a-billion chance that an accident during transport would result in a release of radioactive material. The agency assumed the casks would survive intact, except the seals at the ends might be breached and release some radioactivity.10

Everyone is exposed to ionizing radiation powerful enough to knock electrons out of atoms, damaging DNA and human cells. From natural sources such as radon (emitting alpha particles) and cosmic rays (high-energy protons and atomic nuclei arriving from outer space), someone living in Virginia will be exposed to 300-400 millirem (mrem). That 300-400 millirem is equivalent to 3-4 milliSievert (mSv), another way to measure radiation.

Cosmic radiation increases with altitude because the thinner atmosphere blocks fewer cosmic rays. Virginians living up to 1,000 feet in elevation will absorb an additional 2 mrem, while those living on the Blue Ridge between 3-4,000 feet will be exposed to an additional 15 mrem. Additional radiation emitted from modern coal-fired power plants, TV screens, and even porcelain crowns inside our mouths increase the average human exposure in North America to 620 millirem (6.2 millisievert) annually.11

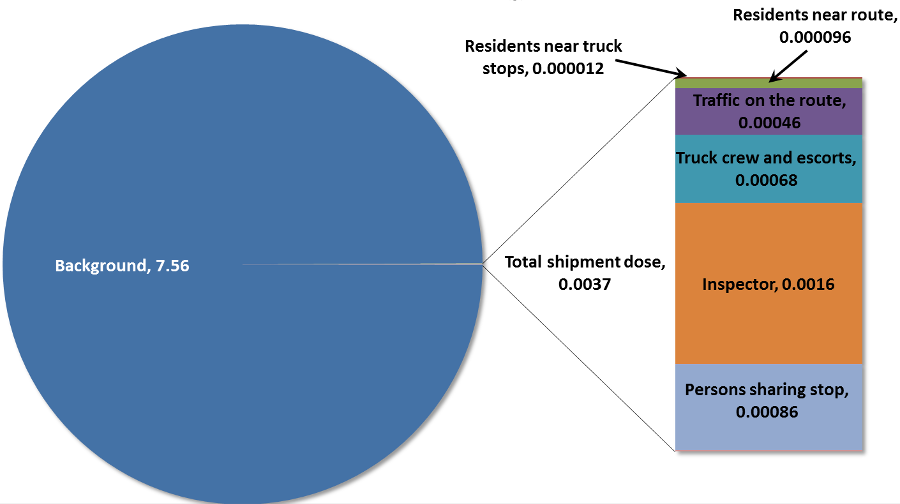

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission concluded that the average additional exposure due to high level radioactive transport in casks would be just .00037 millirem (.0000037 millisievert). In the worst case, however:12

Lifetime exposure limits are 2.5 Sv or 250 rem. The maximum annual permissible dose for occupational exposure, above natural background radiation, is 0.05 Sv (5 rem) annually. A spent fuel shipment accident could expose a person to 40 times the annual maximum, but below what a person living to age 70 could absorb.

collective doses from background sources (7.56 millisieverts/year) far exceed the potential exposure from a truck shipment of spent nuclear fuel

Source: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Spent Fuel Transportation Risk Assessment- Final Report

The largest shipment of high-level radioactive waste will be the transport of 34 metric tons of plutonium from South Carolina to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in New Mexico. In 2000, the United States and Russia agreed to dispose of surplus plutonium, extracted from nuclear warheads, in a way that would prevent re-use of the material in new weapons. The Federal government had planned to convert the plutonium into mixed-oxide (MOX) fuel, recycling it for use as fuel in commercial reactors.

Those plans were abandoned in 2018, after costs to build a plutonium-to-MOX plant skyrocketed. The plutonium will be mixed with non-radioactive material and shipped from the Savannah River site in South Carolina to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico. No plutonium would be transported across Virginia in that process, unless for security reasons the material was loaded on trains and a non-direct route was chosen to limit a potential terrorist threat. There is already a train route through Virginia that has been used without incident for transporting high-level nuclear waste from reactors refueled at Newport News.13

plutonium could be transported between South Carolina and New Mexico by truck

Source: National Nuclear Security Administration, Surplus Plutonium Disposition - Dilute and Dispose Approach (p.9)

the M-140 Naval Spent Fuel Shipping Container may also be used to ship spent fuel assemblies from Newport News to Idaho

Source: US Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board, Naval Spent Fuel Transportation

high-level radioactive waste is transported in specially-designed casks

Source: Department of Energy, Yucca Mountain

transport casks emit less radiation than natural background sources

Source: Department of Energy, 5 Common Myths About Transporting Spent Nuclear Fuel

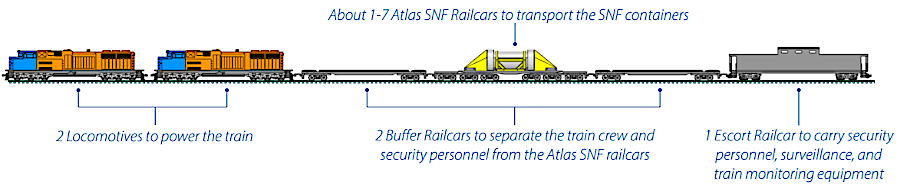

the Atlas railcar is designed to carry spent nuclear fuel (SNF) containers

Source: US Department of Energy, Atlas Railcar