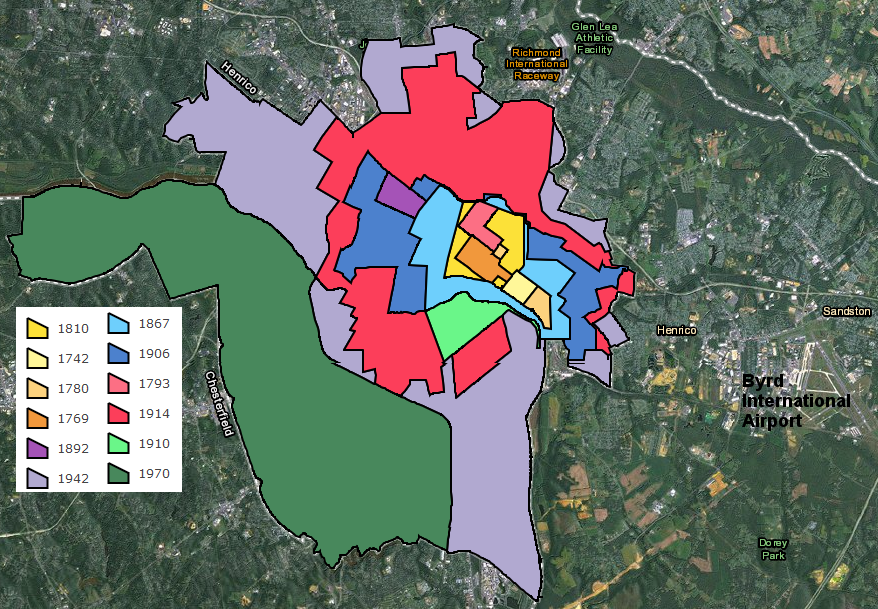

pattern of Richmond's growth through annexations, 1810-1970

Source: City of Richmond, Annexation History Map

pattern of Richmond's growth through annexations, 1810-1970

Source: City of Richmond, Annexation History Map

Virginia's General Assembly always has chartered local municipal governments as subunits of the state government. After starting to create counties in 1634, the first local government charters were granted by the colonial General Assembly to Williamsburg (1722) and Norfolk (1736). The city of Williamsburg and the borough of Norfolk were also authorized to elect a member of the House of Burgesses, as were Jamestown and the College of William and Mary at times before the colonial period ended in 1776.1

The power of "we the people" has never flowed up from the people to a simple hierarchy of local government, then state government, and finally to the Federal governments. All local government jurisdictions in Virginia (cities, counties, and towns) have always been "creatures of the state," created by the colonial and then the state legislature.

Reinforcing the point that local governments are subordinate to state authority, the Virginia Supreme Court has adopted the Dillon Rule. Judge Dillon in Iowa considered local government to be easier to corrupt than state government; he chose to interpret the law so power was concentrated in state rather than local officials.

Virginia law, as interpreted under the Dillon Rule, severely limits the freedom of local governments. The Virginia Supreme Court requires that the General Assembly make a clear delegation of specific authority to local governments, before those governments are empowered to act.

the General Assembly has always dominated local government in Virginia, but it took a civil war in 1861-65 to determine that states were subordinate to Federal decisions

Source: National Archives, View of Capitol, Richmond, Va., April 1865

For example, the legislature has refused to authorize counties or cities to pass an Adequate Public Facilities ordinance. Some counties/cities may desire to use their authority for zoning and building permit approvals to limit development on private property until schools, roads, parks, and other public services meet a local standard of "adequate." Delaying development would, in theory, minimize new traffic congestion and overcrowded schools until new public infrastructure was built and could handle a larger population - but the General Assembly has refused to empower local governments to impose such restrictions.

The General Assembly can revoke authorities it has granted to local jurisdictions. In 1990, the state legislature gave Arlington County the authority to add an additional 0.25% surcharge to the 5% tax on customers staying at a hotel. The extra funding was directed to increase local tourism; attracting visitors to the DC area to come to Arlington increased business activity, which increased local sales taxes and other revenue.

Twenty years later, the county opposed building High Occupancy Toll (HOT) lanes on I-95 and I-495. The county played hardball, even filing a lawsuit accusing state officials of violating civil rights laws because the road impacts would affect neighborhoods with a high percentage of minority residents. The General Assembly retaliated by refusing to renew authorization for the 0.25% surcharge, which had generated $1 million a year for tourism marketing.2

The General Assembly still controls the boundaries of towns and cities; after all, the state legislature created those boundaries in the first place. Virginia towns and cities exist only as subdivisions of the state, not through any independent compact with "the people." Each charter was a unique document reflecting the circumstances of each community.

The distinction between city and town was not significant, except in terms of civic pride, until after the Civil War and a new state constitution was adopted in 1869 under the leadership of Judge Underwood. By the 1902 Constitution, in a confusing evolution of case law and legislative practice rather than by any single act of the General Assembly, Virginia cities had become politically independent from surrounding counties.

Towns have remained subunits of counties, but after the 1902 state constitution was adopted all cities have been treated as independent jurisdictions.

As a result, the distinction between city and town is important now. Until additional revisions in the state constitution in 1970, there was also a distinction between "first class" cities with 10,000 people and above vs. "second class" cities with a minimum of just 5,000 people.

Expanding the boundaries of a town does not remove voters or property tax base from a county. A town boundary shift does redirect certain taxes (automobile registration, consumer utility taxes, and the local portion of sales taxes) from the county to just the town.

Towns are also authorized to impose excise taxes on cigarettes, admissions, meals, and motel rooms, while counties must obtain specific authority from the General Assembly or voter approval in a referendum before levying those taxes.3

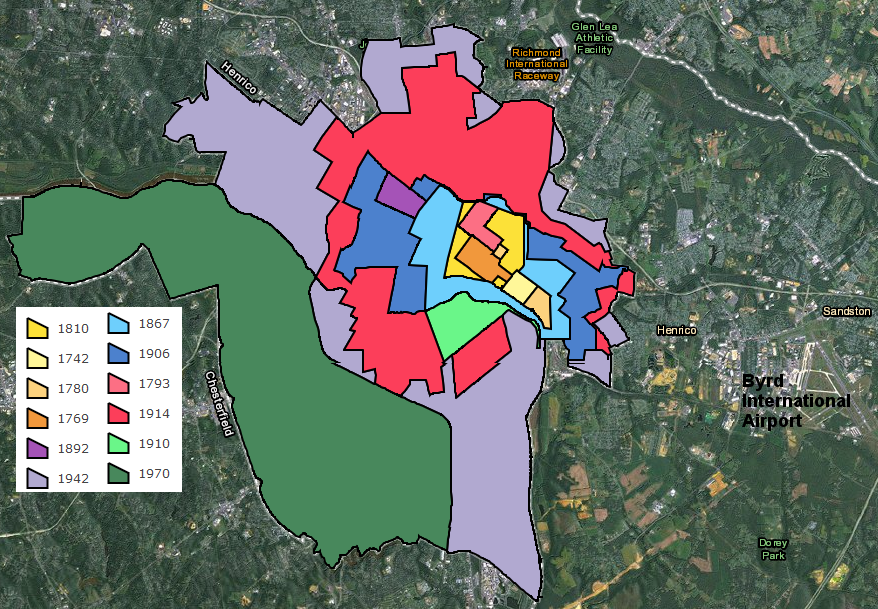

the Town of Blacksburg is a distinct political jurisdiction, but town residents are also residents of Montgomery County and vote/pay taxes in both jurisdictions

Source: Montgomery County, iGIS Map Portal

If a portion of a county is added to a city via annexation, residents in the newly-annexed area no longer get to vote for county officials. New city residents no longer pay any county taxes either.

Cities often draw annexation boundaries to minimize the acquisition of new residents but maximize the acquisition of manufacturing facilities and shopping centers. Residential areas typically require more funding for services (primarily schools) than the residential areas generate in taxes. Counties resist efforts by cities to annex industrial and commercial properties, which generate more revenue in property, sales, and machine tools taxes than those properties require in services.

Cities can annex parts of a county adjacent to the city, changing the status of residents and property owners from county to city. It is a one-way process. Counties can not annex parts of cities, but counties can try to block annexation to maintain existing county boundaries.

Not surprisingly, cities and counties compete to control the property taxes and votes from the periphery of cities, paying lawyers to fight boundary changes in complicated court proceedings.

Cities can annex all or part of towns and counties, but cities can not annex land from other cities. Bitter fights between jurisdictions in southeastern Virginia after World War II led to incorporation of new cities in Hampton Roads, primarily in order to block Norfolk from expanding.

One annexation fight between Richmond-Chesterfield County was driven by an unusual objective: to increase a specific class of residents within city boundaries, and to decrease the percentage of black residents.

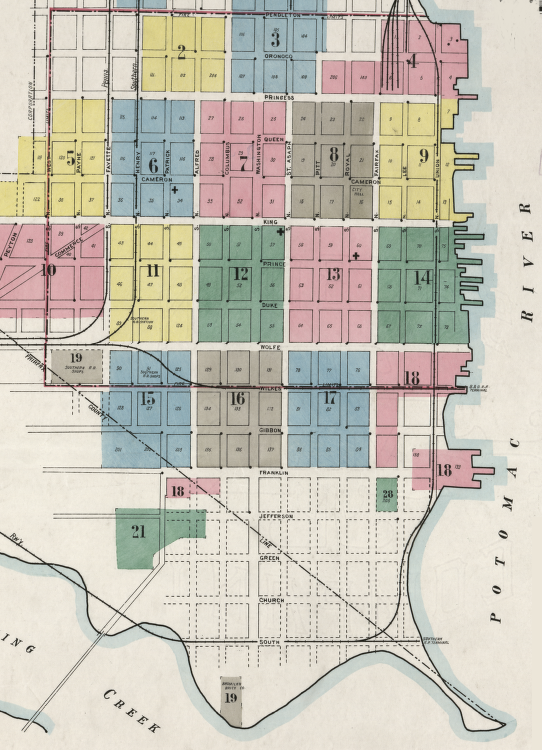

The initial boundaries of Richmond were surveyed in 1737, with 32 squares divided into 4 lots each. The portion of the city between 17th-25th streets, and between Broad-Clay streets, reflects the original core. Since then, 11 annexations and a merger with the City of Manchester in 1911 expanded the size of the city.

After 1942, however, only one annexation by Richmond was successful. After civil rights legislation in the 1960's led to greater political activity among minority-race voters and greater opportunity to vote, the white political leadership in Richmond recognized that black voters would soon be a majority. Since all members of the city council were elected at-large, a black majority of voters would soon be in position to elect an all-black city council.

In response, Richmond's "white oligarchy" proposed annexing 51 square miles of Chesterfield County. The city's efforts to annex parts of adjacent counties were designed primarily to acquire enough "leadership-type white people" to block the city from ending up under the political control of black residents.

A political compromise ended with a 1970 annexation of 23 square miles and 47,000 residents from Chesterfield County. That annexation dropped Richmond's percentage of black residents from 52% to 42%, and added white students to a school system stressed by conflicts over desegregation.

The acrimony associated with that 1970 decision led to the General Assembly's moratorium in 1979 on involuntary annexations of county territory by Richmond and other cities. Legislation passed in 1987 has been extended. All city annexations are now negotiated with adjacent counties, and all city-county boundary line adjustments are voluntary.

Chesterfield officials, soured by the 1970 annexation, limited their cooperation with the city for several generations. The county purchased a 50% interest in the Greater Richmond Transit Company in 1989, but for the next four decades declined to extend bus routes that would facilitate Richmond residents traveling into Chesterfield County. A described by one scholar:4

After Virginia cities were blocked from expanding via annexation, they lost their basic tool for increasing the tax base - annexing commercial property in the suburbs. The General Assembly's moratorium on annexation left cities with just two bad options: cutting services or increasing taxes. Either approach would drive more businesses outside of the city boundaries, and exacerbate "white flight" of wealthy white citizens to the suburbs. The resulting decline in tax revenue made city management and revitalization very challenging.

In 1988 the state legislature offered a third choice. Cities were allowed to convert to town status. Abandoning independent city status and becoming part of a county allowed city official to transfer responsibilities for many government services (especially schools) to the county.5

Richmond's 1970 annexation of a substantial portion of Chesterfield County, though less than originally proposed, led to the General Assembly's ban five years later on annexations by cities

Source: Chesterfield County "Countdown to Jamestown," 1970 Annexation: Chiseling the Horner-Bagley Line

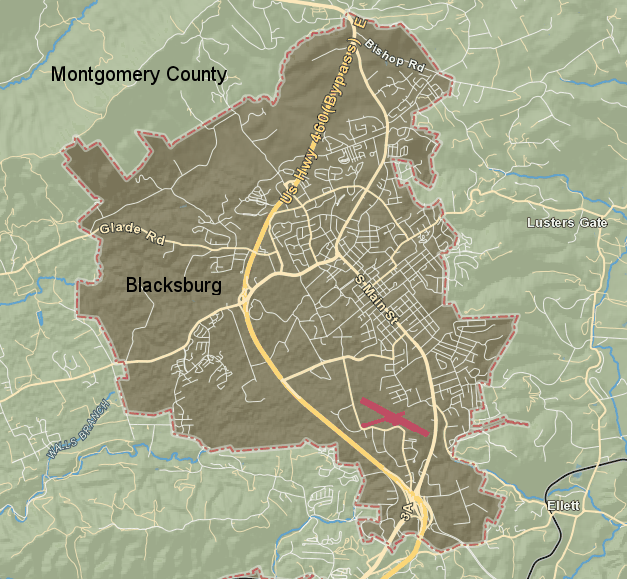

Greater access to water and sewer services may allow for greater density of property annexed into a town, but annexation does not always result in greater development density. In 2013 Morven Park, an 1,000 acre estate in Loudoun County once owned by Governor Westmoreland Davis, proposed incorporation into the Town of Leesburg. Within Leesburg, the zoning ordinance would reduce the potential number of houses on the estate by over 60%.

Morven Park was not seeking annexation in order to subdivide at greater density and build more houses; it sought the boundary line adjustment because the Loudoun County zoning ordinance limited the number of special events that could be held at the facility. Rather than seek to change the Loudoun County ordinance regarding events, Morven Park proposed a change in its political boundaries.6

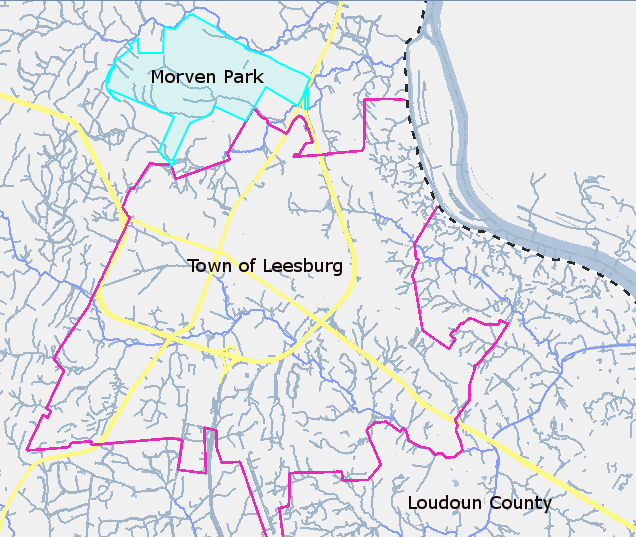

Morven Park requested a boundary line adjustment in 2013, so the land use regulations of the Town of Leesburg would apply rather than the Loudoun County regulations

Map Source: Loudoun County, webLogis - Online Mapping System

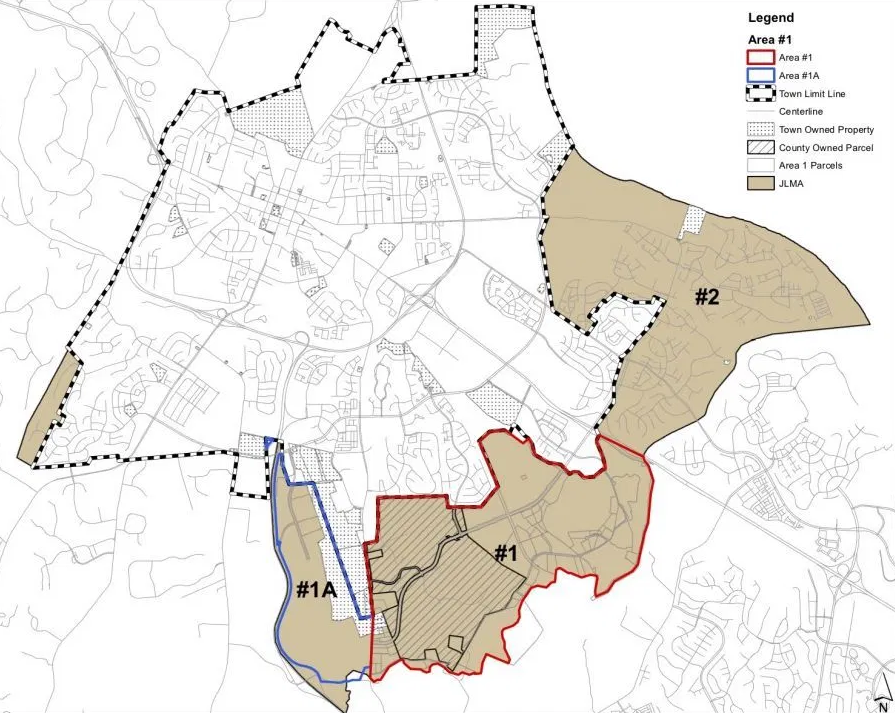

When Leesburg expanded its boundaries in 2020 to include the Compass Creek commercial development between Dulles Greenway and the Leesburg Executive Airport, the town gained the authority to zone land and issue building permits there. Landowners, Loudoun County, and the town successfully negotiated the Boundary Line Adjustment (BLA) without lawsuits. The county and town had agreed on a Joint Land Management Area to guide the development around Leesburg, though they did dispute in court whether Loudoun Water could be the only provider of water service for new development within the Joint Land Management Area.7

Loudoun County established a Joint Land Management Area with Leesburg and other towns to coordinate development planning and boundary line adjustments

Map Source: Loudoun County Board of Supervisors, Proposed Boundary Line Agreement with Town of Leesburg for a Portion of Compass Creek Development

Towns can modify their boundaries through annexations, even if counties object. Towns can also negotiate adjustments of their boundary lines in cooperation with county officials, though town-county disputes can become complex.

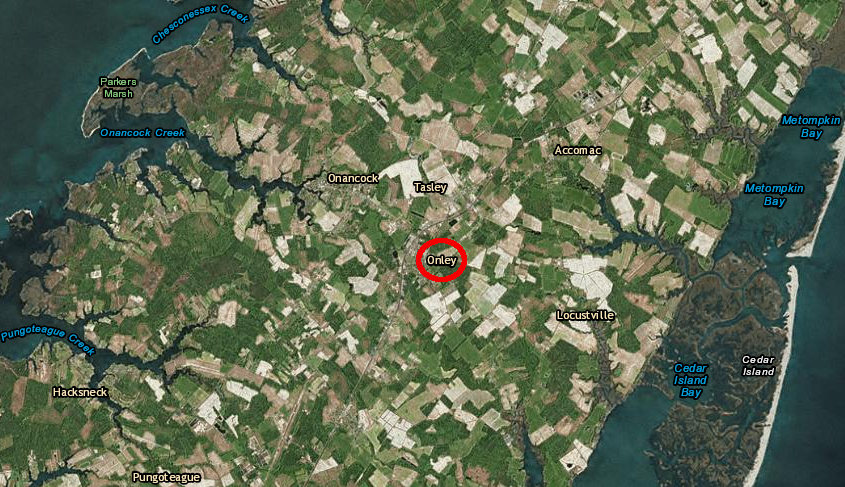

When the Riverside Shore Memorial Hospital on the Eastern Shore decided to replace its 1971 buildings, it also chose to move from Nassawadox to Onley, next to the Four Corners Shopping Plaza. (The town is named after the plantation home of Henry Wise, the only Virginia governor elected from the Eastern Shore.)

The hospital constructed its own public water supply and wastewater treatment facility at Nassawadox, and obviously needed water/sewer services at its new location. The Town of Onley offered neither; all buildings there relied upon private wells for drinking water, and all but a few buildings used septic systems and drainfields for disposal of wastewater.

The nearby Town of Onancock was willing to supply water and sewer services through a simple contract with the hospital, but Accomack County desired to have a greater role in how the area would develop. Town and county officials were in competition with each other regarding who would provide utilities; both sought the opportunity to generate revenue from new growth triggered by the hospital.

In the end, the Town of Onancock agreed to build a waterline to the hospital but transfer ownership to the county, and the county will be responsible for selling water to all customers except for the hospital itself. The decision on sewer services was postponed, because the town's agreement to provide sewer services in that part of Accomack County did not expire for another 5 years. Accomack County is considering whether to build a separate wastewater treatment plant to service the hospital and the new development expected to occur around it.8

the Town of Onancock and Accomack County competed over providing utility services to the relocated Riverside Shore Memorial Hospital in the Town of Onley

Map Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Norfolk was unable to arrange a deal with the city of Virginia Beach for a redevelopment of the Lake Wright Golf Course on the border of the two cities. A developer proposed an outlet mall, to be known as Norfolk Premium Outlets. Despite requests from Norfolk and the developer, Virginia Beach declined to approve the parking and stormwater management pond on the Virginia Beach side of the property. Virginia Beach recognized that it would get just an increase in traffic, while Norfolk would get all the additional tax revenue.9

Compromise is difficult, but far less expensive than the legal process to force annexation; most court decisions altering town-county boundaries now are ratifications of negotiated deals.

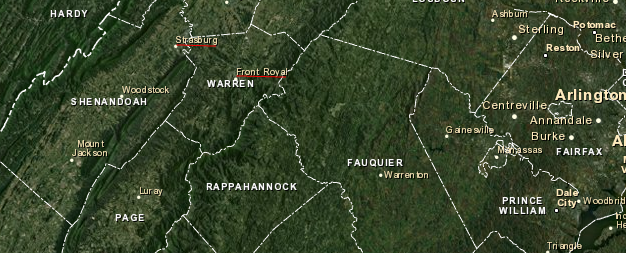

Shenandoah County and the town of Strasburg adopted a long-term annexation agreement in 1984 to establish smooth transitions of areas, and later developed a Joint Land-Use Plan for annexing the Northern Shenandoah Industrial Park into the town. In that 1984 agreement, Strasburg agreed it would never become an independent city and that the town would extend water/sewer infrastructure to the areas that it annexed. In return, the town gained the authority to annex defined areas by simply passing a town ordinance, eliminating any approval delays by state review or legal costs for court proceedings. Annexed areas would be required to pay the additional property tax for the Town of Strasburg in addition to the Shenandoah County property tax, but would no longer be required to pay a 40% premium for sewer service.10

Strasburg and Front Royal are adjacent to I-66, in the Shenandoah Valley west of the Blue Ridge

Map Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Warren County and the Town of Front Royal spent two years negotiating a deal to annex 604 acres into the town, while establishing legally-binding conditions on how the "Confluence Virginia" land could be developed with about 800 homes. The town agreed to annex the land even though the per-house proffer was $12,500 and the original request to fund a new school was $24,000. The Virginia Commission on Local Government objected to the inclusion of the private landowner in the agreement, but the Circuit Court approved Virginia's first three-party annexation agreement in 2014.11

Earlier that year, a Warren County supervisor suggested another option for resolving conflicts between that county and the town of Front Royal: consolidation. Merging the town and county would end the long debate between the two jurisdictions over control of the US340-US522 corridor, but would also reduce the number of elected officials and potentially eliminate the cultural identity of Front Royal. A proposal to merge the county/town was rejected by voters in 1976.12

in 2014, the 604 acres owned by the Front Royal Limited Partnership (FRLP) were annexed into Front Royal

Source: Front Royal Limited Partnership

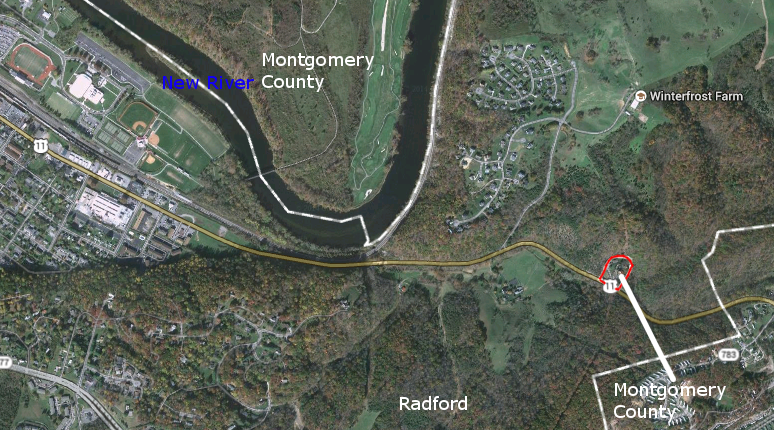

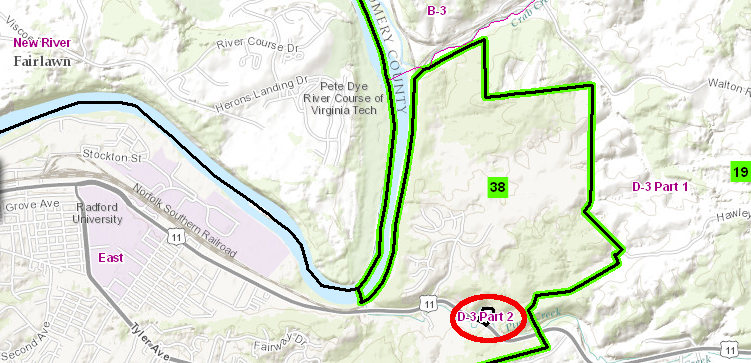

When Radford expanded in 1986 and annexed a chunk of Montgomery County, three residents arranged to stay in the county while all the land around them was added to the city. The people living within the "hole in the donut" continued to pay real estate taxes to Montgomery County, and to vote for county officials (such as the Board of County Supervisors) rather than city officials (such as the Radford City Council). There are other such holes in the donut - the courthouses in Fairfax and Prince William counties are on county land surrounded by the cities of Fairfax and Manassas - but the isolated chunk of Montgomery County within Radford created an unusual pattern in a special election in 2014.

the 1986 annexation created an isolated outpost of Montgomery County surrounded by the City of Radford

Source: Google Maps

In the 2011 redistricting of House of Delegates/State Senate/House of Representative boundaries after the 2010 Census, Montgomery County ended up with 30 voting precincts that were split between voting districts. Keeping the old voting locations - firehouses, schools, etc. - reduced the one-time headache on local officials responsible for finding places where people vote. However, split districts also complicate the responsibilities of poll workers and confuse voters for over a decade until the next Census triggers another realignment of district boundaries.13

One precinct in Montgomery County was split between the 19th and 21st districts - except for those three houses, with a total of three registered voters. They were included in the 38th District for the State Senate, along with the rest of Radford. Montgomery County created a two-part voting precinct, with the majority of the D-3 precinct in Part 1 and three houses in Part 2.

Creating a three-person precinct for Senate District 38 resulted in an unusual situation, where the preferences of the voters were not guaranteed to be anonymous. The State Board of Elections posts official results by precinct and jurisdiction, and the list of people who vote in each election can be purchased from the state.

In the 2011 election, the Republican and Democratic candidates in the 38th District each received one vote. That left some measure of anonymity. When State Sen. Phillip Puckett resigned his seat in 2014, the special election in August of that year required Montgomery County to open just Part 2 of the D-3 precinct.

Only one person in Part 2 of the D-3 precinct voted in that special election. Anyone who obtained the list of voters and used public property tax records to determine who lived on 1200 Norwood Street, 1240 Norwood Street, and 1270 Norwood Street in the Montgomery County enclave could identify who voted for the Republican candidate (and winner) of that race.14

after the 2011 redistricting, Part 2 of Precinct D-3 was completely surrounded by the City of Radford's East Precinct

Source: Virginia State Board of Elections, 2010 Redistricting Maps - Senate

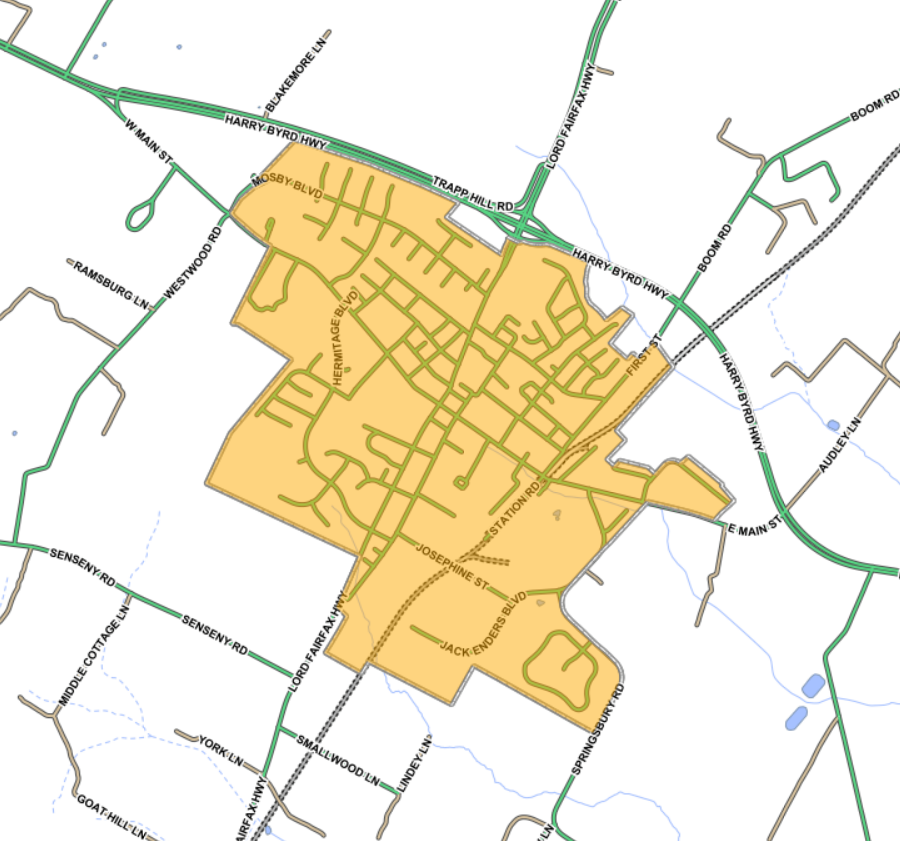

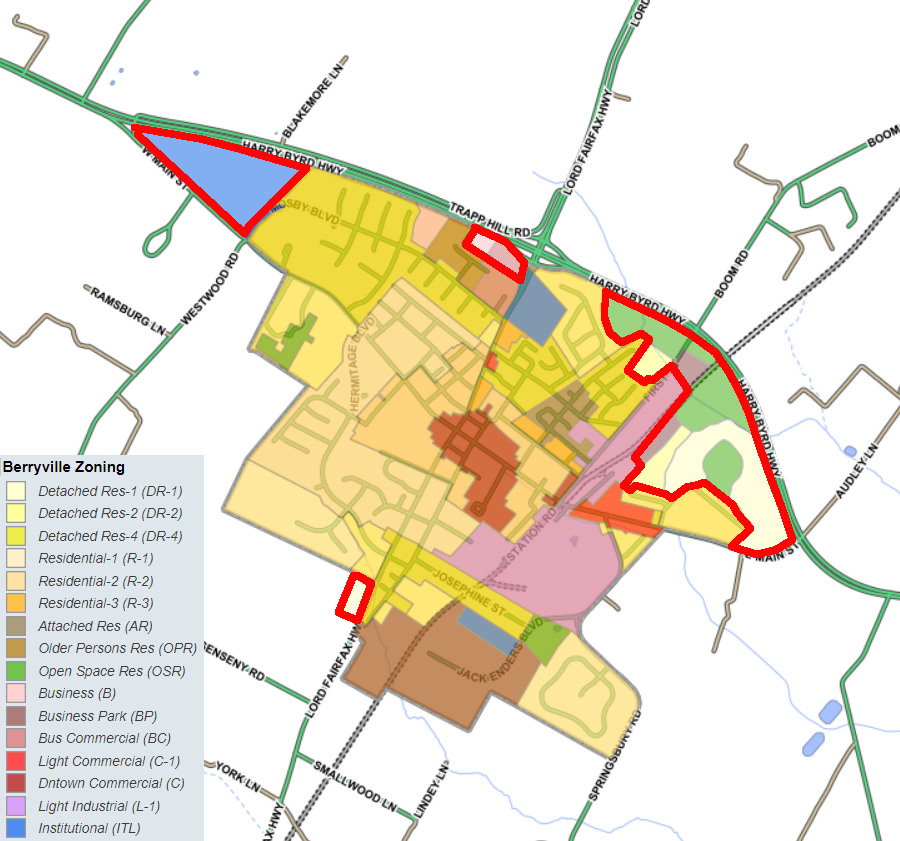

At the start of 2022, the Town of Berryville grew by 130 acres and six residents. The town and Clark County mutually agreed to the annexation. Clarke County officials desired to concentrate population growth at the county's commercial center, because the town could provide water, sewer, police protection, garbage collection, and other municipal services. The town was willing to accommodate new development, anticipating that tax revenue from the new property would offset the additional costs to provide services.15

In contrast, in 2025 Orange County blocked plans of the Town of Gordonsville to annex 1,000 acres and 500 residents. The jurisdictions had discussed a boundary adjustment since 2004. However, after the town's major announced on Facebook that action was anticipated, the negative response was strong.

The town council then decided to consider annexation only from county residents who wanted to be located within the town. The Orange County Board of Supervisors notified the mayor:16

Berryville's town boundaries prior to annexation of 130 acres at the start of 2022

Source: Clarke County, Clarke County Maps Online

Berryville zoning applied to the newly-acquired land starting in 2022

Source: Clarke County, Clarke County Maps Online

The process of annexation kept taxes (as well as services...) low in the counties, and allowed town/city officials to manage logical extensions of services and to shape development that otherwise would occur outside the city boundaries. By 1902, after an annexation the rural counties were no longer obliged to pay for servicing the population and acreage that was incorporated into a city. Counties stayed rural and focused on agriculture, cities offered extra services to landowners and charged higher taxes, and the separation between the rural/developed areas was marked by the city boundary.

since 1912, the City of Alexandria has expanded from its once-square boundaries by annexing portions of Arlington County and Fairfax County, including Jones Point

Source: Library of Congress, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Alexandria, Independent Cities, Virginia

the Town of Occoquan owns parkland in Prince William County, outside the town's boundaries

Source: Historic Prince William, Occoquan - #103