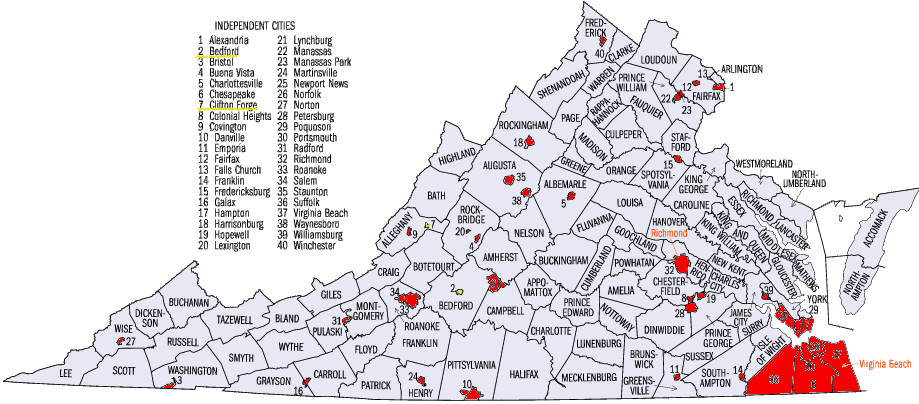

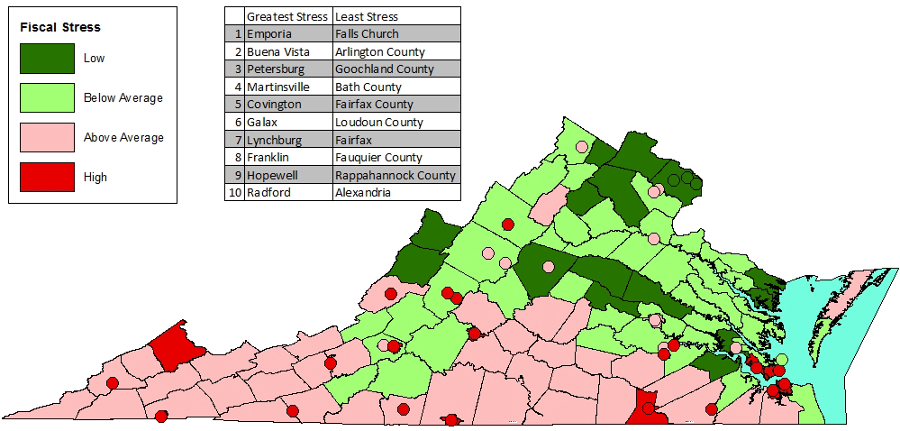

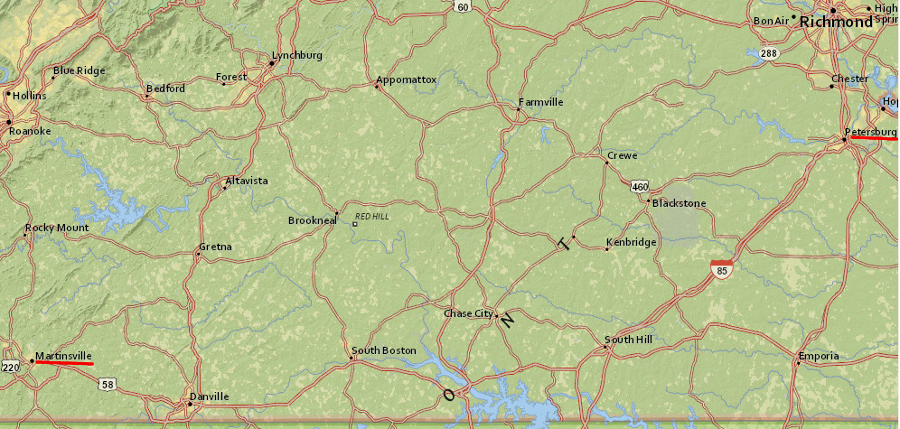

since the Bureau of Census created this map for the 2000 Census, two more cities (Clifton Forge and Bedford) have followed the path set by South Boston and reverted to town status

Source: Bureau of Census

since the Bureau of Census created this map for the 2000 Census, two more cities (Clifton Forge and Bedford) have followed the path set by South Boston and reverted to town status

Source: Bureau of Census

In 2022, Virginia had 95 counties and 38 independent cities. Seven independent cities were created but later eliminated (Jamestown was never incorporated as a "city"):1

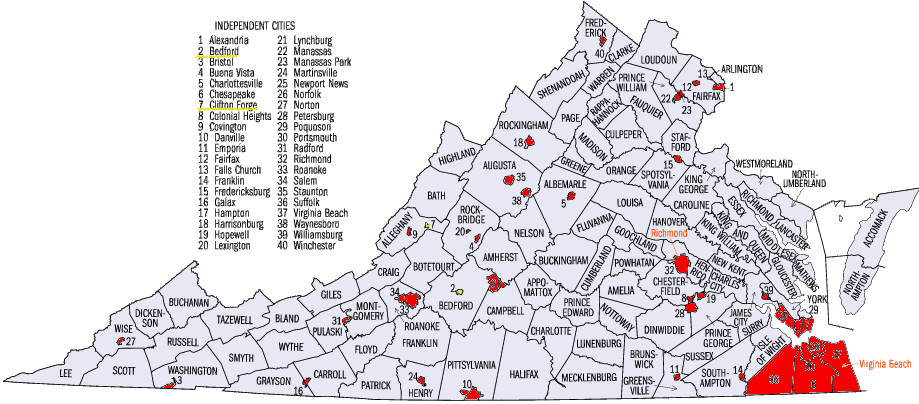

Manchester (consolidated with Richmond in 1910)

Warwick (consolidated with Newport News in 1958)

Nansemond (consolidated with Suffolk in 1974)

South Norfolk (consolidated into new City of Chesapeake in 1963)

South Boston (reverted to town status in 1995)

Clifton Forge (reverted to town status in 2001)

Bedford (reverted to town status in 2013)

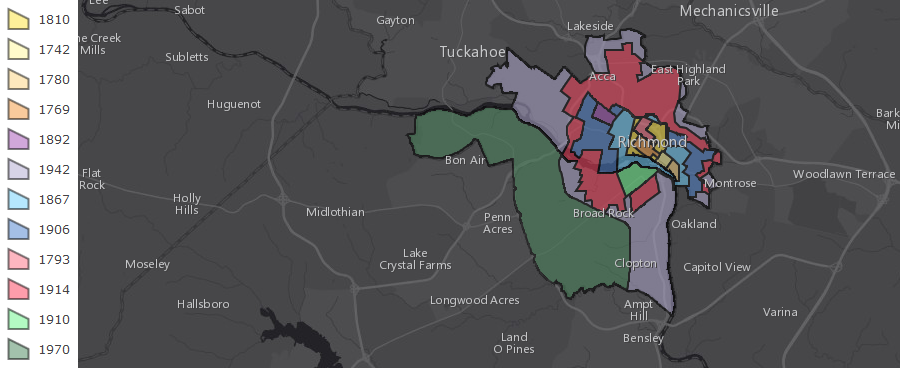

Manchester (shaded purple) disappeared as an independent city when it was absorbed into Richmond in 1910

Source: Virginia Memory, Online Exhibitions, Virginia Department of Public Works, “Map Showing Territorial Growth of Richmond, Department of Public Works, 1923"

Virginia has an almost-unique pattern where cities are politically independent from counties. That independence was formalized in the 1902 constitution.

One result of separate governance is that counties view annexation by growing independent cities as a threat, because annexation of parcels paying property taxes into a city reduces the revenue paid to the county.

Cities receive real estate and personal property taxes for property located within the boundaries of a city. In addition, Virginia shares a portion of the sales tax with the jurisdiction where the store was located. Sales taxes collected at a Wal*Mart located within a county will help support just the county's services, even if most of the customers at the store happen to live across the boundary line within a nearby city.

until 2013, the Wendy's fast food restaurant paid taxes only to the City of Bedford; the Wal*Mart Supercenter paid taxes only to the County of Bedford

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Annexation boundaries are typically drawn to shift properties that generate a positive cash flow to city control. Shopping centers and industrial sites generate more tax revenue than they require in costs to provide public services, since commercial properties (unlike residential properties) add no children to the school system. Cities typically minimize annexation of residential communities, which require more tax dollars than they generate to provide schools, fire/police, library, and other public services.

Many of Virginia's cities have engaged in annexation boundary wars with adjacent counties, with both sides paying expensive legal bills to challenge proposed changes in city-county boundaries. Since 1904 cities could use a judicial process to annex territory from counties, but cities were not able to annex land from other cities.

In Hampton Roads, several counties ended the threat of annexation by getting charters from the General Assembly as independent cities. For example, in 1952 Warwick County became the City of Warwick. Elizabeth City County joined with the town of Phoebus and the City of Hampton, which consolidated to form a larger City of Hampton.

One threat to counties is the disappearance of independent cities when they shift to "town" status. The county gains property tax and sales tax revenue from the area that used to be an independent city, but the additional costs of providing education and social services to former city residents will exceed the additional tax revenue.

After World War Two, retail businesses migrated from city centers to shopping centers in the suburbs, leaving downtown areas with empty buildings. After businesses moved across the political boundary, retail taxes were collected by counties rather than cities. Vacant land in the cities lost value and generated less property tax revenue.

At the same time revenue streams were reduced, cities ended up with higher percentages of low-income residents who required more funding for social services. Better highways and easy access to mortgages for veterans spurred the growth of suburbs after World War II. Middle class residents moved out of cities into new subdivisions in counties, reducing the tax revenue for the cities. Federal and state grants and programs financed some of the growing costs, but city officials were squeezed. Not all Virginia cities found a way to grow tax revenue fast enough to meet increasing demands.

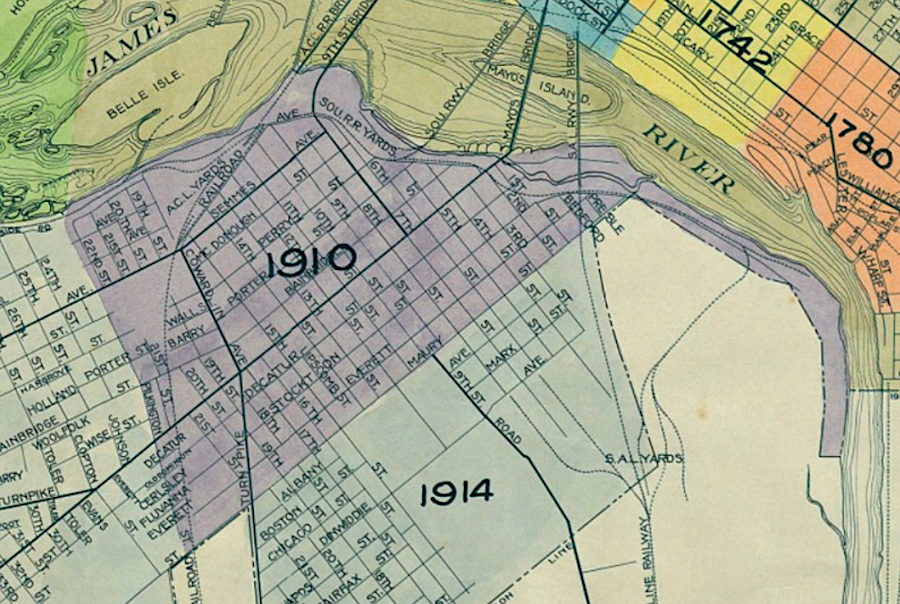

in 2014, incorporated cities were experiencing the greatest fiscal stress in Virginia

Source: Commission on Local Government, Part 1 - Overview and Fiscal Stress

Virginia cities responded by annexing adjacent portions of counties. Parcels with commercial property were key targets, since they generated revenue from property taxes and sale taxes without demanding expensive social services. Annexation boundaries were also drawn to add high-end residential neighborhoods to cities. Though adding houses meant adding students and increasing costs for city school systems, high-priced houses were still tax-positive (paying more in taxes than requiring in services).

Annexation was often a "hostile takeover" by a city, generating political battles and ill-will between cities and counties that lost tax revenue and voters. Residents of annexed districts could not vote on the annexation; instead, state judges determined the new boundary lines.

State law protected cities from hostile annexations, while leaving counties vulnerable. In southeastern Virginia, after World War II all counties protected their territorial integrity by converting to city status. Nansemond County became Nansemond City in 1972, merging with the towns of Holland and Whaleyville. Two years later, the independent cities of Nansemond and Suffolk merged, retaining just the Suffolk name.2

between 1972-74, the City of Nansemond surrounded the separate City of Suffolk

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

Cities sought to annex parcels that were in commercial use. Such parcels generated property taxes but demanded few city services; without houses, there were no children that required classrooms and teachers. Annexed residents were often of higher socio-economic status, and with fewer minority residents, than the cities. Annexations in the 1960's and 1970's bypassed the dispute over busing suburban school children across jurisdictional boundaries to city schools in order to achieve racial balance. When majority-white neighborhoods in Chesterfield County were annexed to Richmond in 1970, those suburban children became students in a city school system that had a majority of black students.

Richmond grew by multiple annexations of adjacent county territory, but since 1979 the General Assembly has blocked annexation by any Virginia city

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 1979, the Virginia General Assembly temporarily blocked the right of cities to annex territory from counties. The temporary ban has never been lifted, and in 2016 it was extended again to 2024. Fiscal stress in cities has increased as businesses and high-income families moved to the suburbs.

Rush hour congestion on I-64 and other streets around Richmond reflects the first stage of city transformation, when workers move outside the city. The growth of Short Pump reflects the second phase, where jobs also migrate outside the city. Relatively wealthy people purchase new houses in the suburbs, and counties get increased tax revenues from the high-priced new houses. Out-migration of wealthy residents leaves cities with a higher percentage of poor people.

As the suburbs expanded after World War II, Virginia cities ended up with less revenue to provide social services for their increasingly high percentage of low-income residents. Raising property taxes to fund increasing costs was counterproductive, when higher taxes triggered more businesses and people to move beyond the city boundary. The old strategy of recapturing residents and businesses through annexation was no longer viable after 1979, and some cities entered a death spiral.

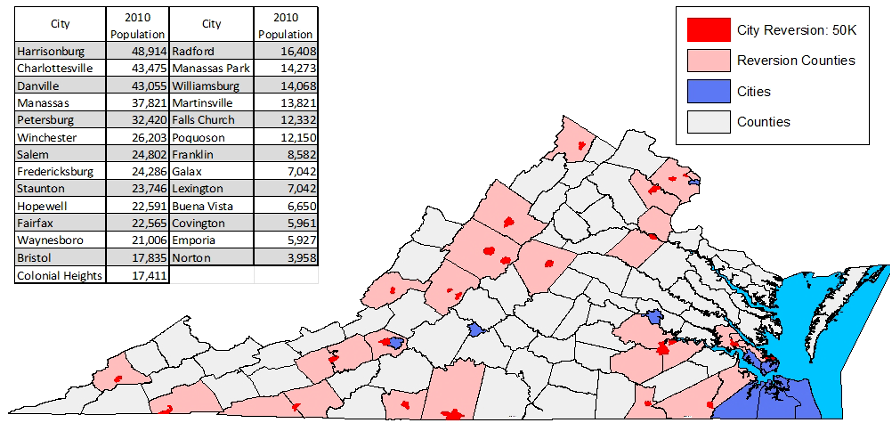

In 1988, the General Assembly authorized cities with less than 50,000 people to revert to town status. There were limits on the option, including:3

Changing a city to town status is the opposite of annexation - land and population are added to the county, rather than removed. Revenues that used to go to the city are directed to the county, including:4

- state payments for salaries and expenses for constitutional officers, such as sheriffs

- property taxes (though towns can impose their own property taxes, in addition to the county taxes)

- local share of sales taxes, state recordation taxes of property transfer documents filed in court

- court fines and forfeitures

- federal, state, and local school operational funds and school cafeteria funds

Despite additional revenues a county will receive after reversion of a city to a town, the process is a threat to the fiscal health of counties. Cities that change to "town" status transfer a high percentage of elderly, low-income residents to the county, and require county taxpayers to absorb additional costs to provide schools and other services to the town residents.

Cities do not revert to town status when they are financially healthy; in that circumstance, cities and counties seeking to consolidate will negotiate a merger with terms that both sides endorse. Reversion is a tool used by cities largely because a county lacks the ability to block the process, even though county residents may strongly object to the financial costs they will have to absorb:5

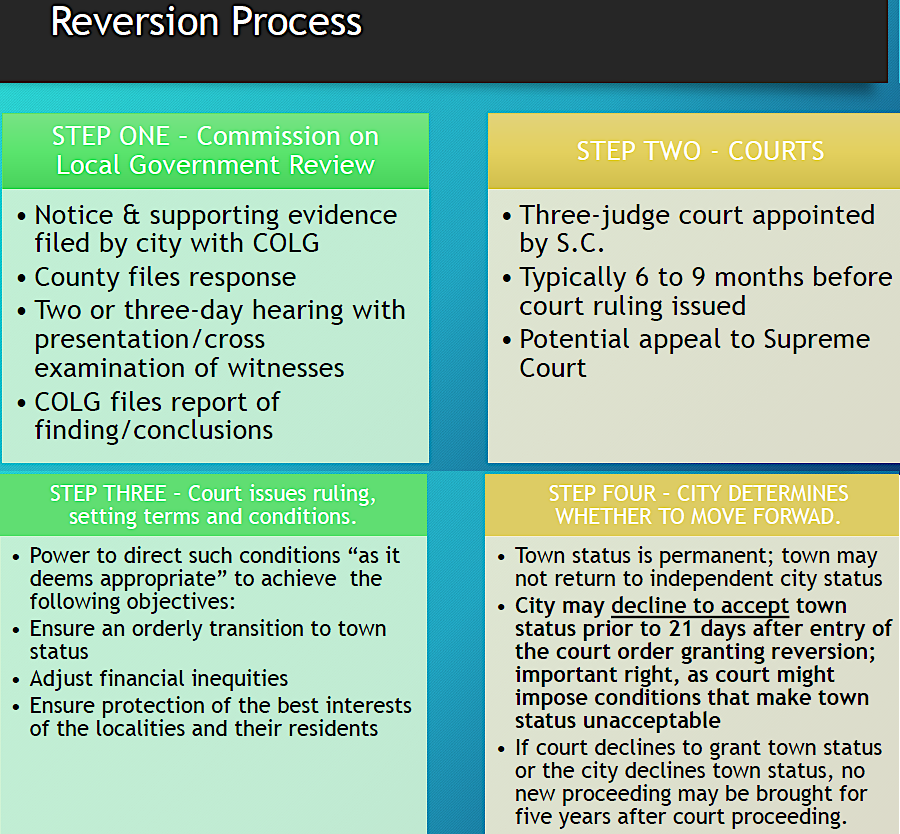

Cities may not become towns unilaterally. Under the 1988 law, the reversion process is managed by the Virginia Commission on Local Government. That agency can orchestrate discussions and public hearings. Final decisions are made by a special court, with three judges appointed by the chief justice of the Supreme Court of Virginia after the Commission on Local Government completes its process.

Those three judges have the responsibility to ensure there will not be substantial impairment to the county's ability to provide services to its existing residents and there will not be a substantially inequitable sharing of resources and liabilities after reversion, but their decisions can be appealed to the Supreme Court of Virginia for ultimate resolution.

To ensure fairness, the special court that manages the transition stays in existence for 10 years. New judges are appointed as needed to fill vacancies that may occur, so the court can "enforce the performance of the terms and conditions under which town status was granted."6

the reversion process from city to town is managed by a special court, after review by the Commission on Local Government

Source: City of Martinsville, Reversion Study Presentation November 19 2019 Council Meeting

The Martinsville City Council formally started the process to revert in 2019. In 2021, city officials thought they had reached agreement with Henry County to convert to town status, but the process was delayed when the Henry County Board of Supervisors rejected the Voluntary Settlement Agreement which had been negotiated. The November 2022 election replaced two supporters of reversion with two opponents, and in January 2023 a 3-2 majority on city council voted to stop the reversion effort.

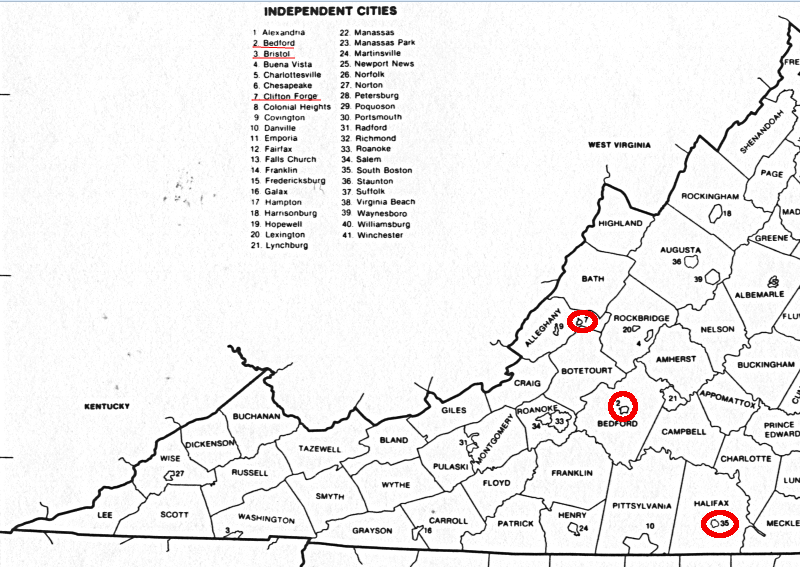

Between 1995-2013, three cities in Virginia reverted to status as "towns" and abandoned their independent status to become part of their surrounding counties:

1995 - South Boston (now a town in Halifax County)

2001 - Clifton Forge (now a town in Alleghany County)

2013 - Bedford (now a town in Bedford County)

the three cities that reverted to town status between 1995-2013 were located in the western half of Virginia

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1990 Outline Map of Virginia (online at University of Texas, Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection)

Fiscal stress forced South Boston, Clifton Forge, and Bedford to alter their status and sacrifice their identity as independent jurisdictions. The three cities had shared costs with their nearby counties for operating school systems prior to reversion to town status, but the cities were still unable to generate enough tax revenue to maintain other public services.

After choosing "town" status, the former cities balanced their town budgets by consolidating some government operations, reducing some services such as the number of police patrols, and shifting costs for funding schools and other services to all taxpayers within the county.

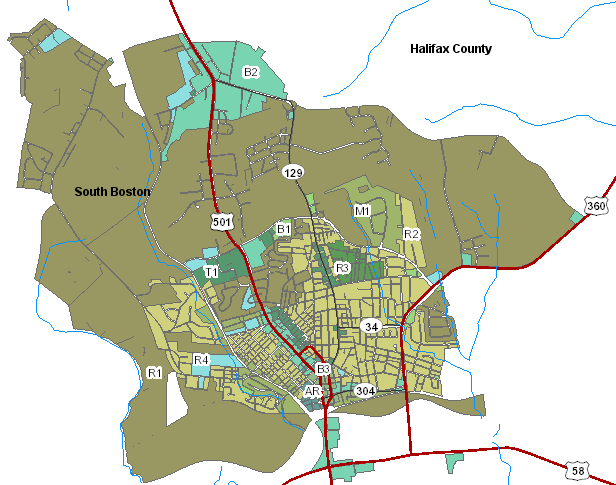

South Boston was the first to abandon its status as an independent city. It had been the Town of South Boston within the County of Halifax until 1960, when it became an independent city. The city then annexed a portion of the county in 1964, but further annexations were blocked by the General Assembly after 1979.

In 1986, the City of South Boston and Halifax County began to explore merger options. Both jurisdictions were relatively poor. The average resident of South Boston had an annual adjusted growth income equal to 79% of the state average, while the average county resident's income was just 63% of the state average. The county had lost population steadily for 40 years, dropping by 18% since 1950. The city still had 17% more people in 1990 than in 1960, but the population had begun to decline in 1980.7

In 1995, South Boston shifted to "town" status. The city council acted despite Halifax County's opposition, which feared complete consolidation of the school systems would require increased taxes or politically-unpopular decisions to close city schools. The city's decision to revert to town status triggered the decision process based on the 1988 law for the first time.

as a town, South Boston retained authority over land use planning; town officials remained responsible for defining zoning districts and approving site plans

Source: Halifax County, WebGIS

In 1995, there were just 7,000 residents in the City of South Boston. Taxes from just those residents, plus state and Federal funds provided through various programs, paid for all city services. After reversion to town status, 29,000 additional residents of Halifax County had to share the cost of providing public services within the boundaries of the town.8

After 1990, residents of South Boston became a separate magisterial district, the eighth voting district within Halifax County. That change resulted in a county board with an even number of supervisors. In the 2001 and 2011 redistricting efforts, the eight magisterial districts were retained. That even number was not unique; Wise and Prince William County also had eight supervisors.

In 2015, the board deadlocked in a series of 4-4 votes and could not elect a chair to serve for the year. One solution was to revise districts to create an odd number (seven or nine), but local officials feared redistricting might be delayed for Federal review under the Voting Rights Act. The board decided to add a ninth member, elected "at-large" in a countywide vote, who will get to vote only in case of a tie. The first Halifax County tie-breaker was elected in November, 2015.9

The City of Clifton Forge and Alleghany County merged their school systems in 1983. Consolidation streamlined operations and reduced administrative costs, but Clifton Forge was unable to maintain its independent status. An effort to consolidate Alleghany County with the City of Clifton Forge and the City of Covington failed in 1987.

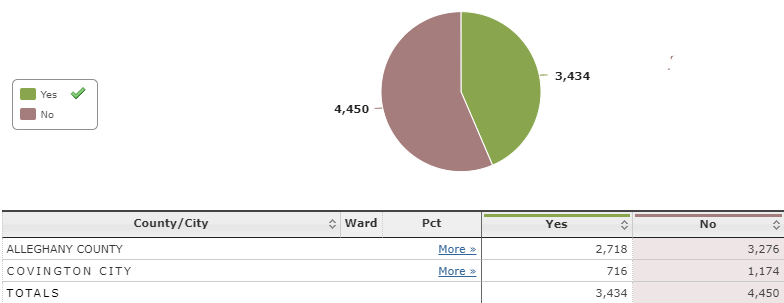

Voters rejected another proposal in 1991 to merge just the City of Clifton Forge and Alleghany County, and Clifton Forge reverted to town status in 2001. Another effort to create the City of Alleghany Highlands, by merging the City of Covington with Alleghany County, was rejected by voters in both jurisdictions in 2011. Covington remains an independent city today, but is discussing merging its school system with the county to reduce costs. The mayor of Covington said in January, 2020:10

Covington remained an independent city after voters rejected consolidation with Alleghany County in 2011

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, 2011 Proposed Consolidation

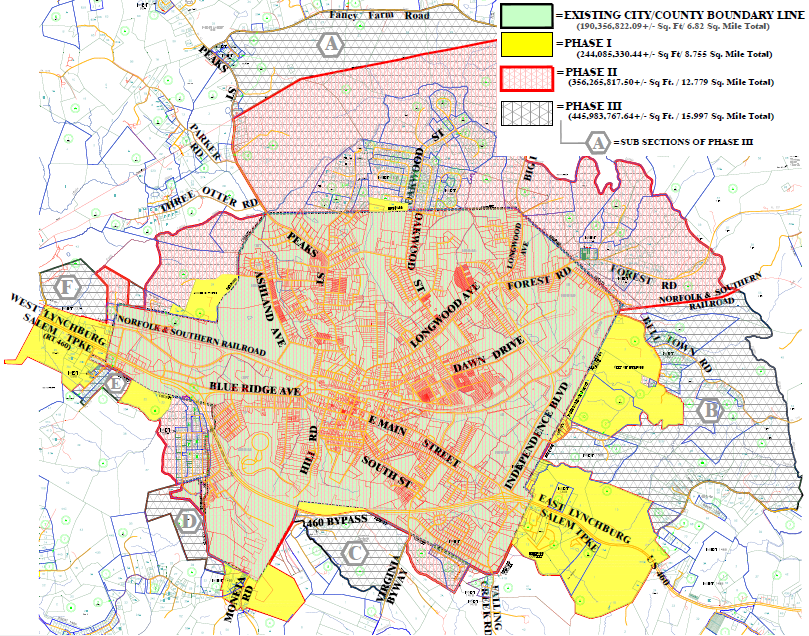

The City of Bedford notified the County of Bedford in 2008 that planned to abandon its status as an independent city. That triggered negotiations which concluded in 2011 with a deal the two jurisdictions submitted to the Commission on Local Government, and ended with reversion to town status on July 1, 2013.

Primary cost savings from the merger came from consolidating the separate city/county water and sewer systems. After reversion, the costs for the city's water system were transferred to a new public service authority, some services (such as recycling) were reduced or eliminated, and the new town budget ended up 20% lower than the old city budget. The elected officials for the Town of Bedford were able to reduce the property tax rate by two-thirds, compared to when Bedford was a city.

Town residents had to pay the county property tax as well as the town property tax after reversion , but the combination of proprty taxes was less than when residents paid just a city property tax. The city's property tax rate had been $0.86/$100 assessed value. In 2014, it advertised an initial rate of $0.82/$100 assessed value. In 2016, homeowners and business in the town paid $0.82/$100 assessed value in property taxes, and the town budget was $9 million compared to $17.5 million before the reversion.

The merger increased the amount of state funding for the local school system. Under Virginia law, jurisdictions receive state funding based on the "composite index." That number is based on a jurisdiction's ability to generate tax revenues, based primarily on assessed value of land within the boundaries of that jurisdiction. The City of Bedford had a lower composite index than the County of Bedford, so the state was paying a higher percentage of the costs to operate the city's school system.

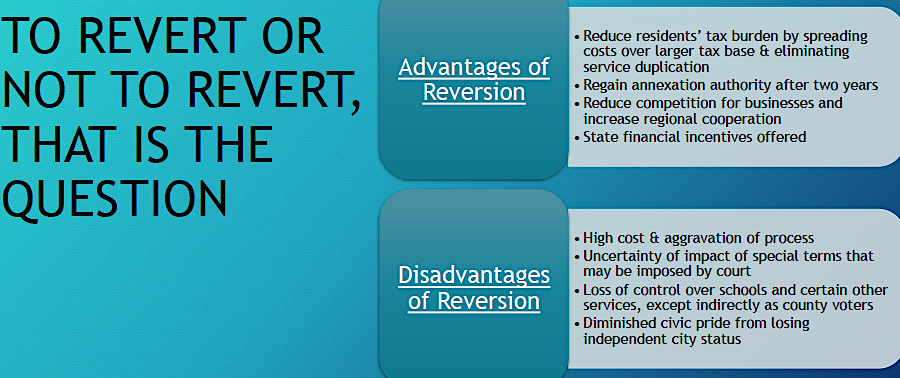

primary arguments for and against reversion to become a town include "diminished civic pride" after losing city status

Source: City of Martinsville, Reversion Study Presentation November 19 2019 Council Meeting

After a city reverts to town status, the state applies the lower composite index for 15 years. Halifax County used the extra state funding over 15 years to build two new elementary schools, after South Boston reverted to town status. Alleghany County used the extra funding, after Clifton Forge reverted to town status, to upgrade the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning system at the county's high school.

The change in city status was relatively smooth for Bedford because the city had previously arranged for Bedford County to manage schools, courts, and social services. The city's school board was abolished, and the county school board managed the city's school system after 2013. The city manager, who became the town manager, noted:11

the reversion agreement between the City of Bedford and the County of Bedford planned for a three-phase expansion of the new Town of Bedford

Source: Reversion Agreement, Proposed Town Boundaries Map

Of the 38 cities in Virginia, those with a population of less than 50,000 people may choose to abandon their charters and become a town without special approval by the General Assembly, and over the opposition of the adjacent counties. The other cities with over 50,000 people would require action by the legislature before altering their status.

If a city decides to become a town, it would gain the authority to expand its boundaries through annexation. That option is not available to cities due to a moratorium imposed by the General Assembly, but there is no moratorium on annexations by towns.12

27 Virginia cities (red) had the option of becoming a town within the adjacent or surrounding county (beige) in 2017, unlike 9 cities with more than 50,000 people (blue)

Source: Commission on Local Government, Part 1 - Overview and Fiscal Stress

If a town generated additional tax revenue after annexation and shifted some costs to the county, then a town council might do something a city council could not achieve: balance the budget.

Petersburg officials discovered they were deep in debt in 2016. The city had been borrowing heavily to pay for annual operations as well as capital investments, and the financial crisis revealed a structural imbalance in revenue vs. expenses. Virginia officials made clear that the state government would not provide a bailout for the city's financial mismanagement, leaving the city few options for recovery. Reversion to town status became a viable, if unpopular, possibility. As described in a Richmond Times-Dispatch editorial titled "Could reversion help Petersburg?"13

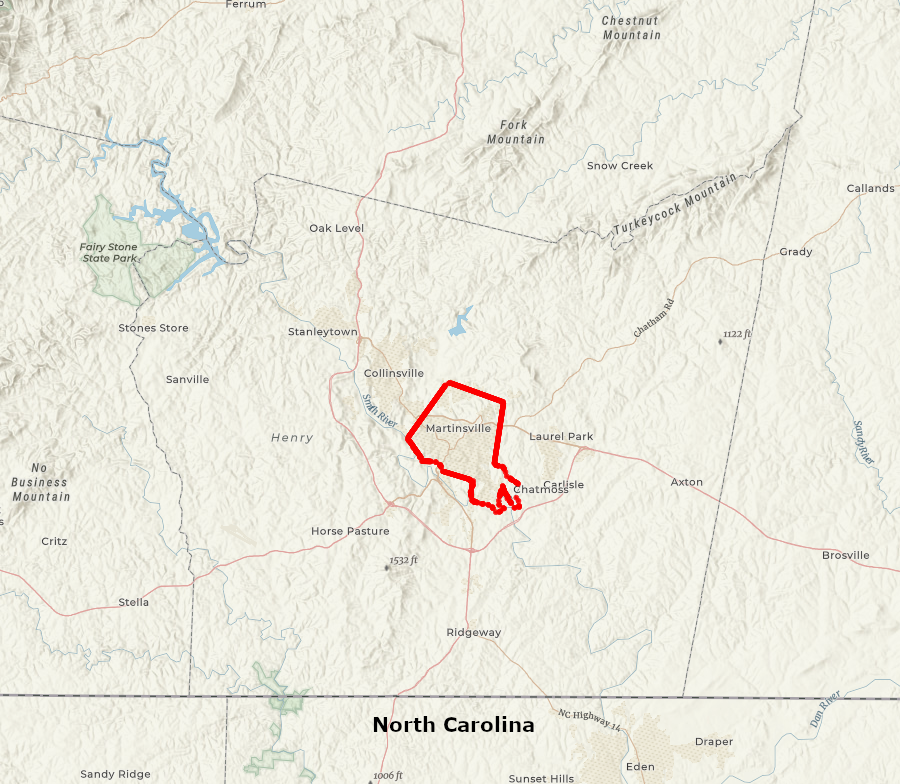

The City of Martinsville committed to reversion to town status in 2019. Henry County continued to oppose that reversion through 2021.

in 2016, fiscal stress caused leaders in Martinsville and Petersburg to consider reversion to town status

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

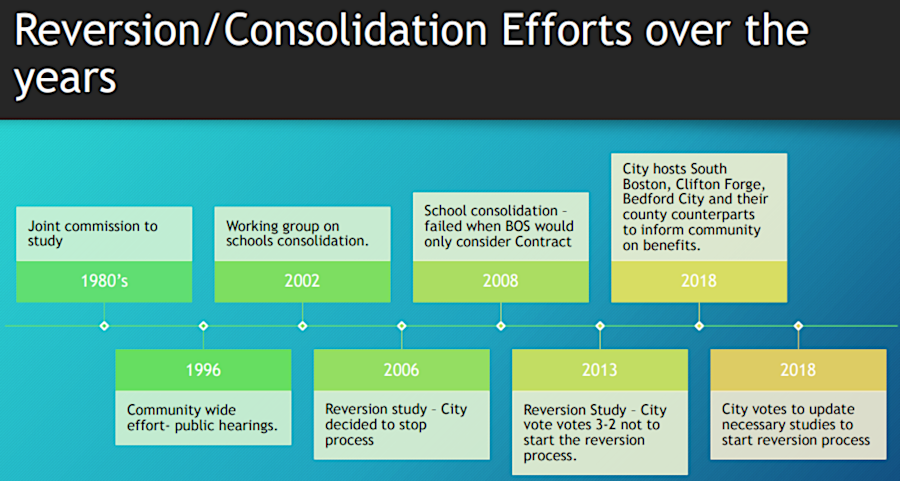

In 2005, 2013, and 2016 Martinsville officials considered reversion to town status, anticipating it would result in substantial reductions in taxes. The city and surrounding Henry County maintained independent school systems, missing out on opportunities to minimize costs for administration and maintenance. Local charitable organizations contributed half of the $40,000 cost for a study to consider consolidating them, but talks ended when Henry County insisted that the study examine only the option of Martinsville contracting with the county for operation of the city school system.

Martinsville and Henry County have considered reversion since the 1980's

Source: City of Martinsville, Reversion Study Presentation November 19 2019 Council Meeting

Martinsville's mayor asked Henry County officials in 2017 to discuss cooperative measures to reduce costs, but the county supervisors were not willing to talk until the city developed specific proposals. County residents were reluctant to increase their taxes by having Martinsville revert to town status, and city residents were reluctant to dilute their political authority by merging with the county. The local paper reported a response by the mayor to a citizen's question that provided a lot of wiggle room for changing the city's status:14

That changed in 2019. Despite opposition from Henry County supervisors, who proposed restarting discussions on merging school systems, the Martinsville City Council voted 5-0 to initiate the process of reverting to a town. The mayor said:15

Bill Wyatt in the Martinsville Bulletin reported that at the time, the Henry County property tax rate was $0.555 cents per $100 of assessed value. The tax rate for property within the Martinsville city boundaries was almost double at $1.0621 per $100 of assessed value. An analysis by Martinsville stated that if the city reverted to town status and the county had to provide the same level of services already being received by city residents, then Henry County taxes would have to rise by $0.05 per $100 of assessed value.

City real estate taxes would become town taxes, and they would drop by $0.60 per $100 of assessed value. However, town residents would have to pay county as well as town taxes, so reversion would increase taxes of Henry County property owners by 10% but leave town residents paying the same amount as before reversion. In addition, the city's initial financial assessment did not include the transfer of costs to the county for maintenance and operation of the city's jail.

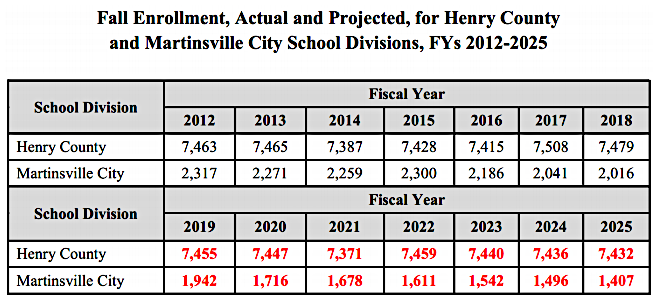

A key factor was the city's higher cost for operating its school system. The number of students in Henry County was projected to decline slightly between 2019-2025, but the city was expected to lose 25% of its school population during that time period. The number of students in Martinsville would drop from 1,942 to 1,407, and operating costs per student would become unsustainably high for the city.16

the number of students in Martinsville was predicted to drop much faster than in Henry County

Source: Troutman Sanders report to City of Martinsville, Transition from City to

Town Status (p.12)

Pushback against reversion and an alternative solution came from the Martinsville Commissioner of Revenue. She emphasized in 2020 that the city was not broke, or at risk of having expenses exceed revenue. The three cities which had reverted to towns, Clifton Forge, Bedford and South Boston, all had populations less than half that of the almost 13,000 residents in Martinsville. In 2020, eight cities and 22 counties had smaller populations, and they were managing to stay solvent.

The Commissioner of Revenue, who had been elected first in 2001, claimed that businesses in Martinsville would have a higher tax rate if the city became a town even if the real estate tax rate was lower. She suggested the city/county could address their financial hardships by consolidating the separate school systems, but offered another alternative:17

If the two jurisdictions consolidated into a city, then her office would be retained and the position of Henry County Commissioner of Revenue would disappear.

After she spoke on December 10, 2019, the City Council voted 5-0 for the city to revert to town status. It adopted the City Manager's perspective that Martinsville was never going to have a tax base adequate to fund revitalization of the city:18

Martinsville is located in the center of Henry County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In the 2020 General Assembly, bills proposed to give Henry County veto power over the reversion process. To ensure the new legislation would not be applied retroactively, the Martinsville City Council voted again unanimously in January 2020 approving a resolution memorializing the previous decision:19

As in 2006 and 2014, the General Assembly did not pass a bill that would require Henry County's approval before Martinsville could revert to town status. The city retained the capacity to act, and the county had only the opportunity to react. It created a website with relevant documents and a Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) page which expressed the county's views, noting that a tax increase of $0.05 per $100 of assessed value to fund a larger school system, housing and managing more inmates, and other "services on which the City makes no money" would be a 10% tax increase for county residents.20

In 2020, the Henry County Board of Supervisors was told that the city's economic condition was strong. It had maintained 10% of its annual budget in reserve, and the four enterprise funds for electric, water, sewer and refuse disposal services had accumulated $6.5 million. The average debt per person was lower than the statewide average.

County officials speculated that the driving force for reversion to town status was the potential for a "Town" of Martinsville to annex land from the county. Cities were blocked from annexation by a statewide moratorium. If Martinsville reverted to town status, then it could expand town boundaries and impose property taxes on additional land starting just two years after the change of status.

City officials argued that their objective was to eliminate duplication of administrative overhead, eliminating some constitutional offices and streamlining operations of schools and the courts. County officials were advised that the county had a different priority:21

The two jurisdictions reached a Voluntary Settlement Agreement (VSA) in 2021 after extensive discussions and mediation. That ended the potential for a lengthy and expensive series of lawsuits.

Henry County agreed to support the conversion of Martinsville from a city to a town. The county decided that it could not block reversion legally or get the General Assembly to intervene, so it bargained instead. The two jurisdictions negotiated the first reversion deal that consolidated school systems. The county agreed to shared taxes from the Martinsville Industrial Park with the future town, and the city agreed not to annex any county property into the town for the next decade.

The attorney representing the city stated at the end of the process:22

The positions of constitutional officers in the city were to be eliminated. The schools, courts, sheriff and jail operations and property were to be transferred from the city to the county, though the county would have to pay rent if it wanted to use the existing courtrooms within the Martinsville Municipal Building. Henry County agreed to create a new magisterial district for the town to elect a member of the Board of Supervisors and the School Board.

The town would retain ownership of its utility system, and Henry County Public Service Authority agreed to continue as a customer. Martinsville would continue to fund its share of costs for regional groups such as the Blue Ridge Regional Library, the Economic Development Commission, the Blue Ridge Regional Airport Authority, and the 911 Communications Center.23

The last sticking point in the negotiations was the date of reversion. The city sought to complete the process in 2022, while the county proposed 2024. They agreed to allow the decision to be made by the Commission on Local Government, or by the three-judge panel appointed by chief justice of the Supreme Court of Virginia. The Commission on Local Government recommended July 1, 2023.24

The negotiated agreement collapsed in December, 2021. The Henry County Board of Supervisors rejected the Voluntary Settlement Agreement in a 4-2 vote. That created the possibility that the process would shift to a contested reversion proceeding. In a lengthy and expensive contested reversion process, lawyers representing Martinsville and Henry County would seek to get a panel of state judges to establish new terms for the reversion.

The next day, Martinsville notified Henry County that it intended to force reversion through court action. The letter made clear that the city viewed the Voluntary Settlement Agreement as its last effort to negotiate a deal, and in the upcoming legal process would drive a harder bargain. The city made clear that in a contested revision it would retain the right to annex Henry County land two years after reversion, while in the Voluntary Settlement Agreement (VSA) Martinsville had agreed to wait ten years:25

Martinsville residents decided that they wished to retain their status as an independent city. They elected two new members to City Council in November, 2022 who opposed reversion to town status. In January, 2023 the new city council, by a 3-2 vote, abandoned the effort to become a town.26

The population in the city had declined 25% between 1980 (18,149 residents) and 2020 (13,485 residents), but those remaining preferred city status.

The 2024 General Assembly passed a new law requiring that Martinsville residents had to approve reverson to town status in a referendum. In the future, such votes would be binding on the City Council rather than just advisory.27

downtown Martinsville

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online