Local Government Autonomy and the Dillon Rule in Virginia

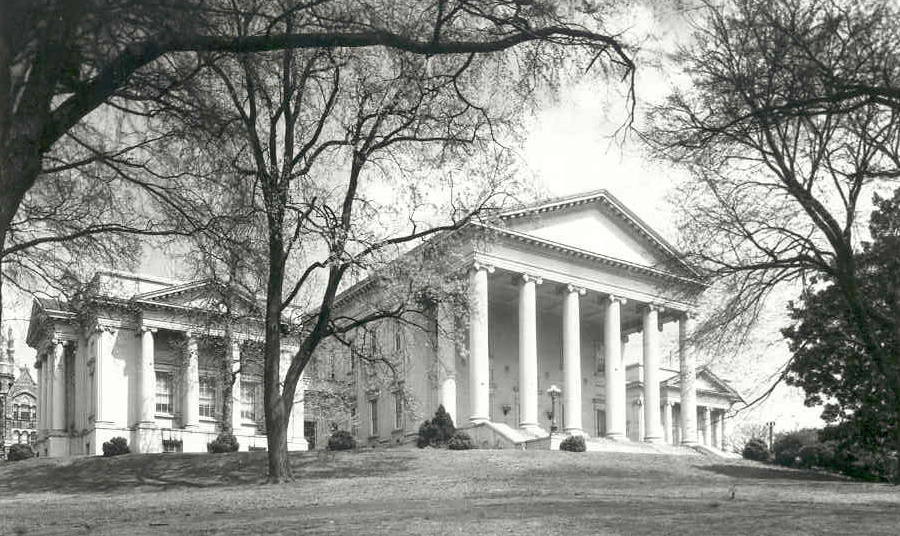

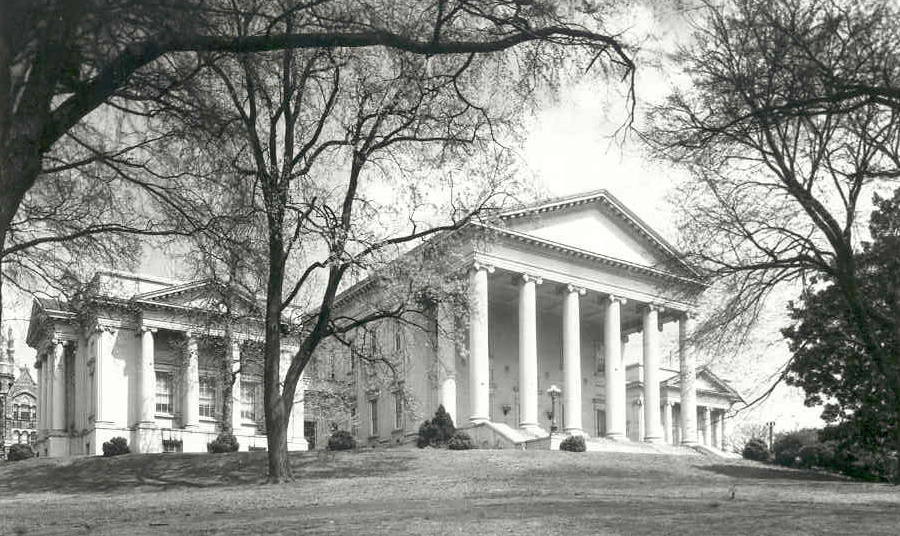

the Dillon Rule, which the Virginia Supreme Court adopted in 1896, is a legal principle that local governments have limited authority, and can pass ordinances only in areas where the General Assembly (which meets in the state capitol in Richmond) has granted clear authority

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, National Register Nomination: Virginia State Capitol, Richmond

Virginia is a "Dillon Rule" state, not a "Home Rule" state. Local governments have limited authorities. It has required an act of the General Assembly in Richmond before a Virginia county could open its schools before Labor Day, alter speed limits for vehicles traveling through school zones, or levy a standard fee on all households to cover the cost of managing a landfill.

Local governments in Virginia do not have the power to establish a moratorium on rezoning land, expand the definition of "family" so same-sex partners qualify for health insurance, or require a proposed uranium mine to compensate nearby property owners if concerns regarding radioactivity lowered values of nearby properties. Local officials have no control over which businesses are granted a liquor license; the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority has total authority. A candidate for governor once complained that his home city, Norfolk, required state approval before enacting a pooper-scooper ordinance to require cleaning up behind a dog.

The General Assembly had to pass a special law before Arlington County had the authority to hire an independent auditor (inspector general) as a county employee. A separate law was required to permit the county to ban smoking at the county-owned Lubber Run Amphitheater.

James City County had to get its charter modified in 2019, in order to gain authority to remove junk cars that were still intact, but inoperable and without a valid inspection sticker or license plates. The vote for the charter change was 38-0 in the State Senate and 99-0 in the House of Delegates, but until the legislature acted the county did not have full authority to manage abandoned vehicles.

The town of Altavista had to get a special law passed in 2020 before it could offer discounted water/sewer rates to low-income, elderly, or disabled customers. The General Assembly had previously granted such authority to just Richmond and the town of Louisa. All other jurisdictions must charge the same rate to all of their residential customers.1

The Dillon Rule give the state legislature the capacity to meddle in small-scale decisions made by local jurisdictions. Municipal (town, county and city) governments may adopt an ordinance only if the General Assembly has clearly granted authority for the local government to make decisions on that topic.

The state legislature has defined in state law which authorities have been delegated from the state government to all jurisdictions of a particular category. For example, town and city councils have been granted the right to implement a meals tax, but until 2020 elected supervisors in a county could tax restaurant meals and prepared foods only if local residents vote for approval in a referendum on that issue. The 2020 General Assembly changed the limits and granted counties equivalent authority.

In 1992, voters in Fairfax County had rejected a meals tax. Another referendum in 2016 was also defeated by a 56-44 margin. In 2020, the chair of the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors supported the General Assembly when it increased authority to impose local taxes without getting voter approval first in a referendum.

The chair contrasted how supervisors in Fairfax County representing 1.2 million people had limited ability to make decisions, but the state had granted greater authority to the city council in the adjacent City of Alexandria with just 159,000 residents:2

- The real issue here is equity... It's absurd that the tiny city of Alexandria has far more authority to implement taxes than Fairfax County.

Locality-specific delegation of state authority also occurs when the General Assembly issues or modifies municipal charters, and through special legislation. In 2012, the General Assembly modified the Code of Virginia and authorized Pittsylvania County supervisors to impose an annual solid waste fee to fund the landfill in Dry Fork.

The $60/year fee was intended to raise about $1.2 million so revenue from county taxes could be redirected towards repaying school bond debt. County officials wanted a simpler process for collecting revenue from those who used the landfill, and planning operations at the landfill would be easier with a predictable income. Though the supervisors created exemptions for residents who took their trash to other facilities, the fee was viewed as a tax increase and remained controversial. The supervisors cancelled the fee just before the 2015 elections.

Nonetheless, a member of the House of Delegates representing the county got the House of Delegates to approve a bill (in a 97-0 vote) to modify the Code of Virginia again and withdraw state authority for the local fee. County officials managed to derail the proposal in the State Senate, delaying consideration for another year. The 100 Delegates and 40 State Senators in the General Assembly still have ultimate authority over that county's ability to charge residents a $60/year trash fee.3

because Virginia is a Dillon Rule state and the charter for Pittsylvania County does not empower local officials to establish a standard solid waste fee, county supervisors must have special legislation approved by the General Assembly in order to charge landowners $60/year to operate the Pittsylvania County Landfill

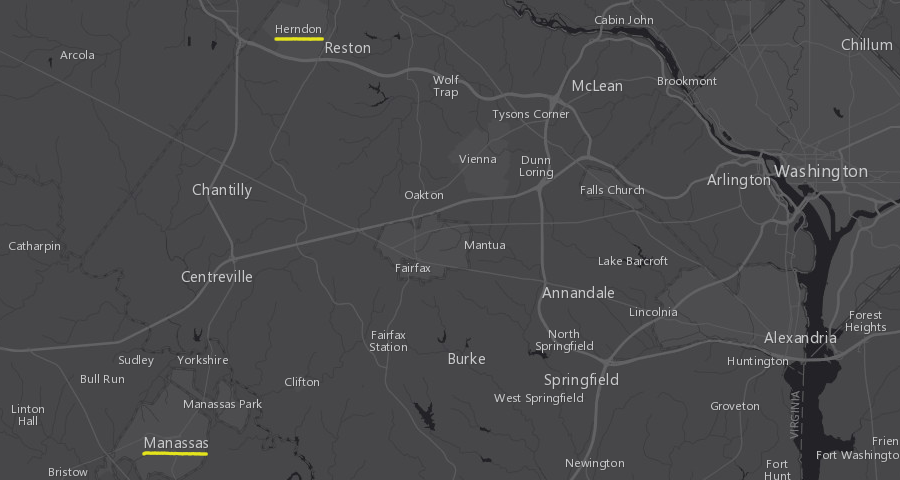

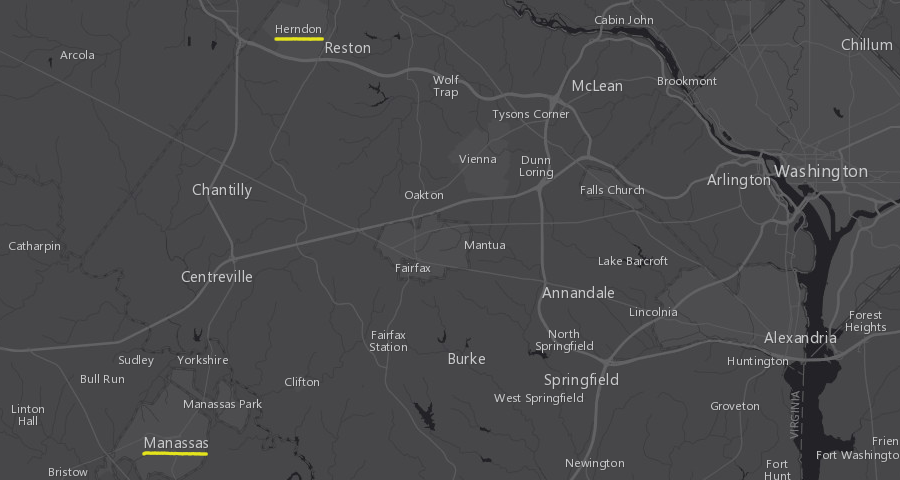

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 2015, Herndon requested the General Assembly to modify the town charter and move town council elections from May to November. More people participate in the November elections, especially every four years during a presidential contest.

Manassas had made that switch in 2014, even though the campaigns of local candidates are occasionally swamped by the campaigns for the US Congress, President, and Governor. After the change in the election date, Manassas voters elected a Democrat to the City Council for the first time in decades.

The General Assembly refused Herndon's request in 2015. Democrats immediately claimed that Republicans in the House of Delegates were being partisan, and that they feared the increased number of Democrats who typically vote in November elections.

The Herndon Town Council then revised the election date through a local ordinance. Approval by the General Assembly was required to institutionalize the change in the charter, however, and a future town council could have revised the local ordinance and re-scheduled Herndon's local elections in May. In 2021, the General Assembly passed a law forcing all municipal elections to be held in November. At the time, both houses of the legislature were controlled by Democrats, and the Governor also was a Democrat. The objections of both local governments and Republicans were not sufficient to change the decision.4

the General Assembly revised the charter for the City of Manassas in 2014 so elections for council/mayor would occur in November, but after the city elected its first Democrat the Republican-controlled state legislature blocked a similar request in 2015 to alter Herndon's town charter

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 2015, many communities in southern states to examine the public placement of over 1,000 memorials honoring the Confederacy after nine black people at a church meeting in South Carolina were murdered by a white man who used Confederate symbols to express his racist beliefs. Portsmouth, Charlottesville, and other communities began reconsidering if those monuments should be moved, perhaps into museums. In 2018, Alexandria decided to rename "Jefferson Davis Highway." City Council chose to use the name for the road in Fairfax County, "Richmond Highway."

City officials considered multiple options without the state having any role in the decision. The General Assembly allows cities to rename their primary highways, but counties have not been granted equivalent authority.

Arlington County assumed it could not change the name of Jefferson Davis Highway without special legislation from the state legislature, which had named the road "Jefferson Davis Highway" in 1922. The Attorney General proposed another option in 2019; the Commonwealth Transportation Board had gained the authority in 2012 to rename most transportation facilities once the local jurisdiction made a request. Cities did not need to use that option, but the Attorney General did identify how a state agency rather than the legislature could help a county rename a road.

By 2021, Fairfax, Arlington, and Prince William counties plus the cities of Alexandria and Richmond had committed to change the name of Jefferson Davis Highway to Richmond Highway. Chesterfield, Stafford, Spotsylvania and Caroline had not submitted requests to the Commonwealth Transportation Board to make a change.

The murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor had spurred a new push for equity and social justice, which led to removal of many Confederate monuments and renaming of public places. The General Assembly was unwilling to wait for the remaining jurisdictions in Virginia to voluntarily rename the highway. State legislators demonstrated once again that they had more power than local governments by mandating that all jurisdictions rename their portion of Jefferson Davis Highway. Localities were allowed to choose a replacement name, but those who failed to act by the deadline would see the state rename the road "Emancipation Highway."5

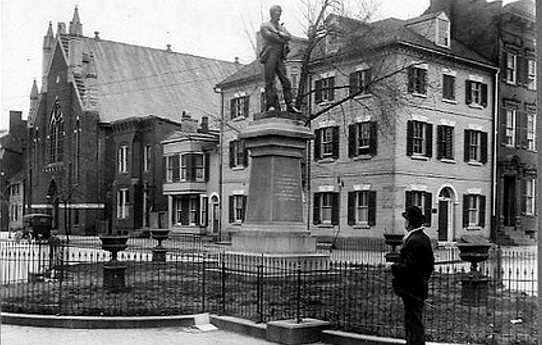

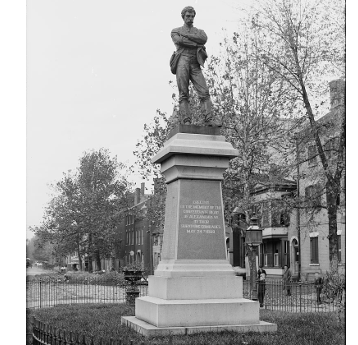

Nearly every Virginia jurisdiction was constrained by a law passed by the General Assembly in 1998 that prohibited local governments from altering monuments to wars and veterans. Statues of Confederate generals were common on city-owned or county-owned land across Virginia, and almost every courthouse lawn has featured a memorial to Confederate military units and soldiers.

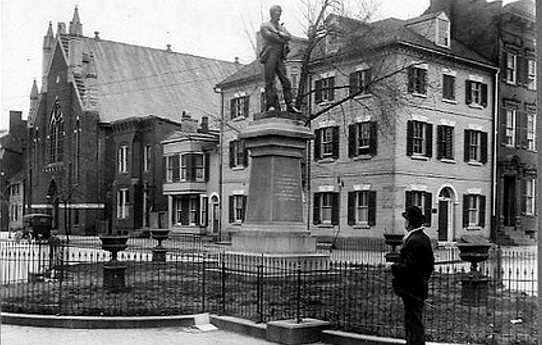

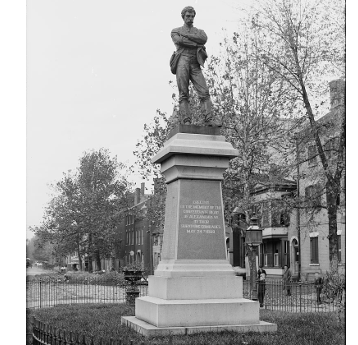

Sources: District of Columbia Public Library "Commons," The Confederate Memorial in Alexandria, Virginia and Library of Congress, Confederate monument, Alexandria, VA

since 1889, the "Appomattox" statue in Old Town Alexandria at the intersection of Prince and South Washington streets has been a highly visible reminder of Virginia's Confederate past

The City Council in Danville removed the Confederate flag from a memorial where the flag had been displayed for two decades outside Sutherlin Mansion, the last building in which the Confederate Congress met in 1865. Virginia's Attorney General had ruled that the 1998 law applied to monuments honoring veterans and wars, but not to memorials honoring buildings such as Sutherlin Mansion. Advocates of displaying the flag then sued to force the City Council to restore the flag, but the local Circuit Court judge ruled that the 1998 law applied only to war memorials erected after the law was passed.

In response to that ruling, the General Assembly passed a new law in 2016 to amend the Code of Virginia and make the war memorial protection retroactive. That law was intended to block Portsmouth and other local governments from relocating historic Confederate monuments prominently displayed on city streets, but Governor Terry McAuliffe vetoed the act.

In his veto message, he opposed a state-directed "one size fits all" approach that prohibited local governments from having the flexibility to deal with different situations:6

- Pursuant to Article V, Section 6, of the Constitution of Virginia, I veto House Bill 587, which overrides the authority of local governments to remove or modify monuments or war memorials erected before 1998...

- ...There is a legitimate discussion going on in localities across the Commonwealth regarding whether to retain, remove, or alter certain symbols of the Confederacy. These discussions are often difficult and complicated. They are unique to each community's specific history and the specific monument or memorial being discussed. This bill effectively ends these important conversations.

in 2015 the Portsmouth City Council, representing a city with a population with a majority who identified as "Black or African American alone" in the 2010 Census, sought to move the 19th Century monument To Our Confederate Dead from its prominent location at the corner of High and Court streets

Source: Library of Congress, Confederate Monument, Portsmouth, VA

There was a significant political change in the General Assembly after the November 2019 elections. Democrats gained control of both houses of the legislature for the first time in 20 years, and they had a different perspective on honoring Confederate leaders.

In 2020, the General Assembly passed new legislation that granted local governments the power "to remove, relocate, contextualize, or cover any such monument or memorial on the locality's public property." That shifted the political burden to county, city, and town officials, and granted enough flexibility so each community could decide the fate of military memorials within the boundaries of a jurisdiction. The 2020 changes allowed a locality to hold a referendum on whether to alter a monument, but did not require such a vote.

The legislature carved out two specific exemptions. Local governments were not allowed to make decisions on monuments and memorials located in a publicly owned cemetery, and the City of Lexington was prohibited from altering any on the grounds of the Virginia Military Institute.7

The Dillon Rule also limits the power of local school boards and school district superintendents. School officials manage the most expensive government service provided by Virginia government, K-12 education.

School superintendents are paid accordingly, though each school district has a different pay scale. In 2015, rural/suburban Botetourt County hired a new superintendent with a base salary of $170,000, while urbanized Fairfax County paid a base salary of $265,000. Those salaries reflected the complexity of the job managing school systems - but at the same time, the salary of the governor of Virginia was only $175,000 per year.

Despite the high compensation to attract and retain quality superintendents, the General Assembly has not given those local officials the basic authority to determine when school will start each year after summer vacation. The 140 state legislators who meet in Richmond for 30-60 days for annual General Assembly sessions define the start of the school year.

In 1986, the state legislature banned school systems from starting classes before Labor Day. The traditional explanation is that the law protects the tourism industry, ensuring a supply of high-school age workers at the end of the summer. The Virginia Hospitality Travel Association (called the Virginia Restaurant, Lodging and Travel Association after 2015) lobbied successfully for decades to preserve the ban, by highlighting the economic activity generated during the Labor Day weekend and by making significant contributions to key legislators.

The traditional name for the 1986 legislation is the "Kings Dominion" law. That reflects the significance of ensuring the availability of workers, and before-school-starts visitors, to that one attraction.

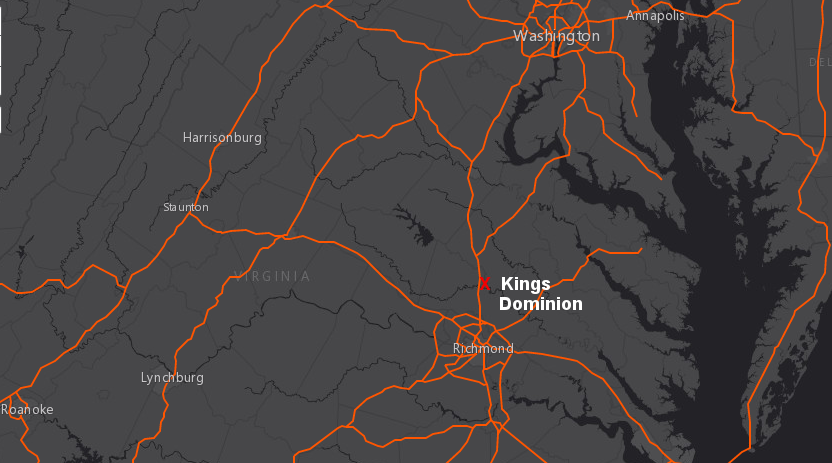

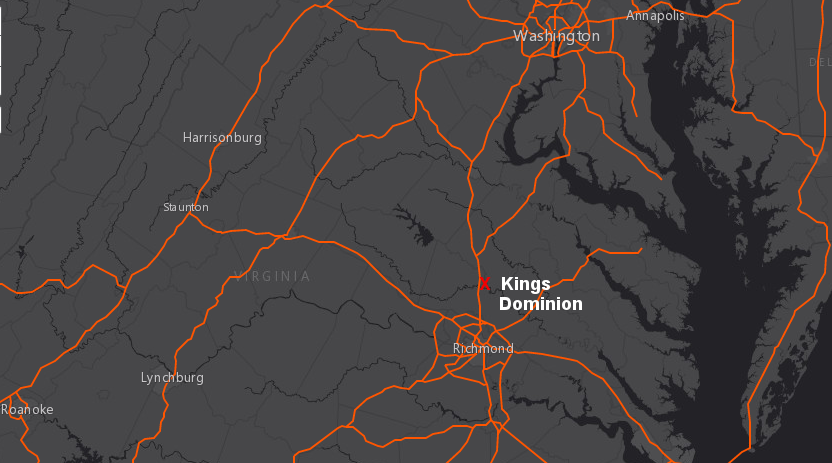

the Kings Dominion law is named after the amusement park located on I-95, north of Ashland

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

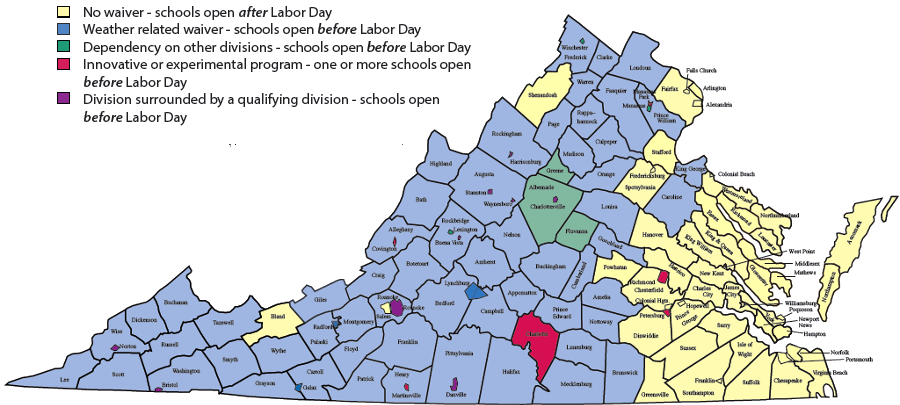

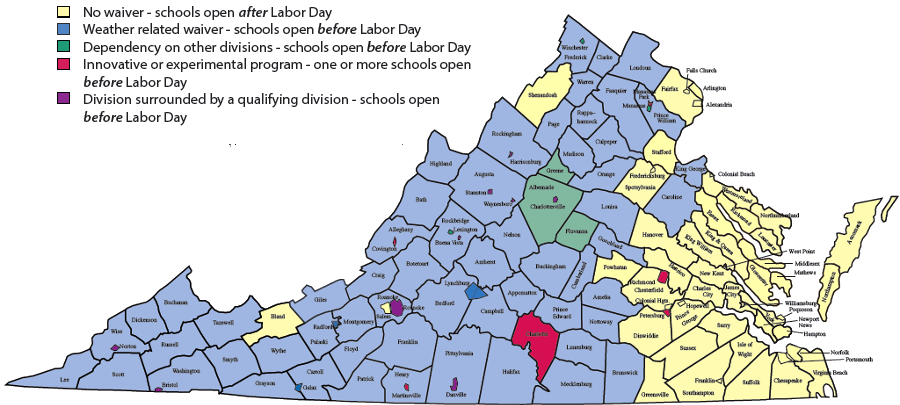

The tourism industry focused on the delaying the opening of school systems along the I-95 corridor and in Hampton Roads. By 2004, 79 of the 132 school districts in Virginia had obtained waivers by 2004 through various justifications in the Code of Virginia. By 2018 most school districts west of I-95 opened before Labor Day, due to the number of days the schools are forced to close due to snow:8

- A school division has been closed an average of eight days per year during any five of the last 10 years because of severe weather conditions, energy shortages, power failures, or other emergency situations.

Virginia is a Dillon Rule state, not a Home Rule state, so the General Assembly can dictate to local jurisdictions when schools will open after summer vacation

Source: Virginia Department of Education, School Division Openings 2015-16

In 2019, the state legislature finally loosened its restrictions on local school boards. All school districts were allowed to open two weeks before Labor Day, so long as they make a four-day holiday for Labor Day weekend. Schools with waivers to open three weeks before Labor Day had to change their calendars to fit the new two-week limit. School administrators were supportive, since an earlier opening would allow more time for students to prepare for national standardized tests, including Advanced Placement tests for students who would go to college.9

Centralizing authority and limiting the power of local government has been the "Virginia way" ever since the English colonists arrived in 1607. Political power has always been centralized, and the extent of local control by towns/cities/counties in Virginia has always been constrained.

Each of the 50 states has a constitution which serves as the contract between the people and powers they grant to the state government. State governments create municipalities and delegate authority to those municipalities to manage schools, roads, and other public services. Virginia has three types of local municipal government - towns, cities, and counties - while other states also have boroughs, townships, parishes, and other forms.

States that give great flexibility to local jurisdictions are known as Home Rule states. In Home Rule states, local governments can make public policy decisions, such as creating special zoning and tax districts to finance a specific infrastructure project (arena, road, etc.), unless the state has specifically limited local authority. Municipalities must comply with state constitutions, limits included in municipal charters from the legislature, and in some cases expressly imposed limits, but local officials have substantial flexibility to make decisions that reflect local concerns without additional state approval.

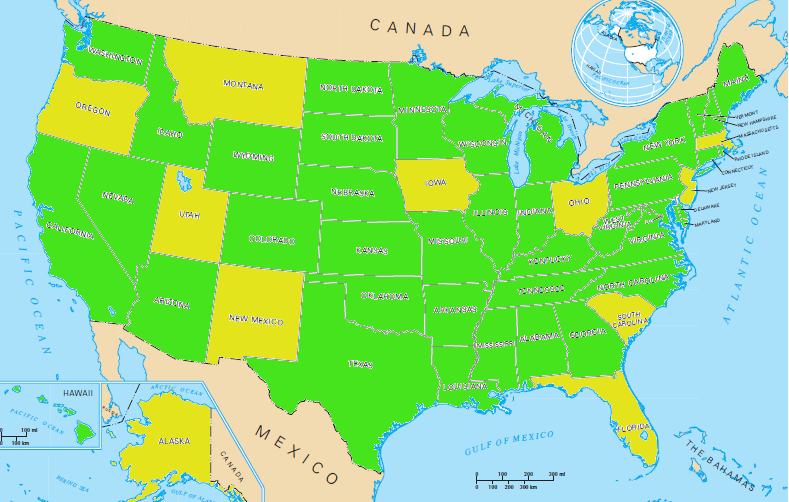

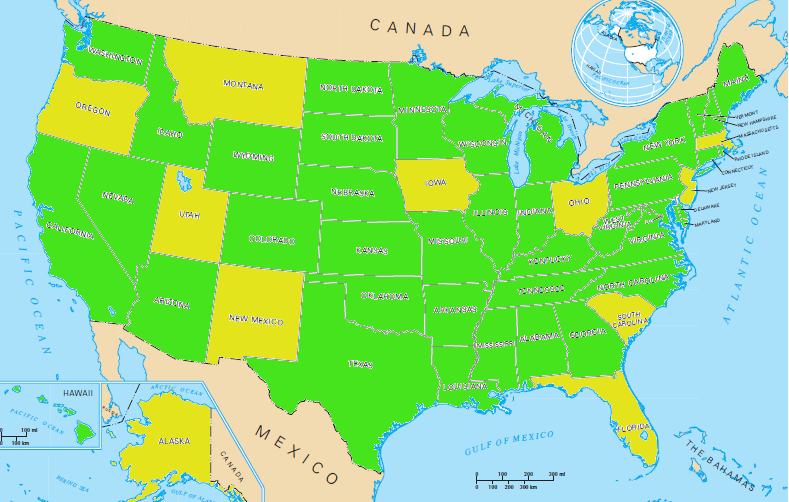

In contrast, the 39 states that follow the Dillon Rule authorize local governments to make decisions only in specifically-authorized areas; without clear authorization by the state legislature, local officials are blocked from taking action. The contrast between local flexibility vs. strict construction is described in West's Encyclopedia of American Law:10

- Home rule... gives municipalities room to experiment with new approaches to government without first seeking approval from the state. It also allows municipalities to act more quickly on issues of local concern because they do not have to seek approval for their actions from the state legislature.

- ...Under Dillon's Rule, municipalities exercise only the limited powers specifically granted by the state, the powers necessary to carry out the specifically granted powers, and the powers indispensable to the declared purposes of the municipality.

the 50 states limit the authority of local jurisdictions via the Dillon Rule or empower those jurisdictions via Home Rule in different ways with a wide variety of legal interpretations, but 39 states (in green) use the Dillon Rule most often

Source: Brookings Institution, Is Home Rule The Answer? Clarifying The Influence Of Dillon's Rule On Growth Management (2003)

The Albemarle County Land Use Law Handbook elaborates:11

- the Dillon Rule provides that localities and governing bodies have only those powers that are expressly granted, those necessarily or fairly implied from expressly granted powers, and those that are essential and indispensable...

- There is no presumption that an ordinance is valid; if the General Assembly has not authorized a particular act, it is void.

Localities may claim they are passing ordinances that implement state-granted powers, such as regulation of towing services or landfills, and affected businesses and landowners may disagree. Individual lawsuits to resolve such conflicts have created case law where state courts have defining, situation by situation, what powers have been granted to localities. In some cases, such as local efforts to control the aesthetics of new development through zoning, the General Assembly has acted to clarify the extent of local control and grant specific authority for architectural review in designated historic districts.12

The Dillon Rule is named after the chief justice of the Iowa Supreme Court, John Forrest Dillon. In the 1860's, he considered local governments to be more corrupt than state governments, and sought to limit the power of local officials to sign contracts. In his decisions and later Commentaries on the Law of Municipal Corporations, he established a legal principle that that local jurisdictions had no inherent powers granted by the people; all authority flowed from the state.

The contrasting approach was articulated by a Michigan judge, Thomas M. Cooley. According to Judge Cooley's legal philosophy, local governments have all powers except those explicitly forbidden by the state constitution or state law.

Judge John F. Dillon established the Dillon Rule while a state judge in Iowa

Source: Iowa GenWeb, Annals of Iowa (1909)

Judge Dillon's approach limited the power of local officials and strengthened state control. If there was any confusion regarding whether state authority had been granted, if the grant of authority from the state was not expressly conferred by the legislature through a municipal charter or law, then the local jurisdiction had - according to Dillon's legal interpretation of the state constitution in Iowa - exceeded its power and the local ordinances were not valid.

Describing his strict construction of local authority, Judge Dillon wrote:13

- ...a municipal corporation possesses and can exercise the following powers, and no others: First, those granted in express words; Second, those necessarily or fairly implied in or incident to the powers expressly granted; Third, those essential to the declared objects and purposes of the corporation, not simply convenient, but indispensable. Any fair, reasonable doubt concerning the existence of power is resolved by the courts against the corporation, and the power is denied.

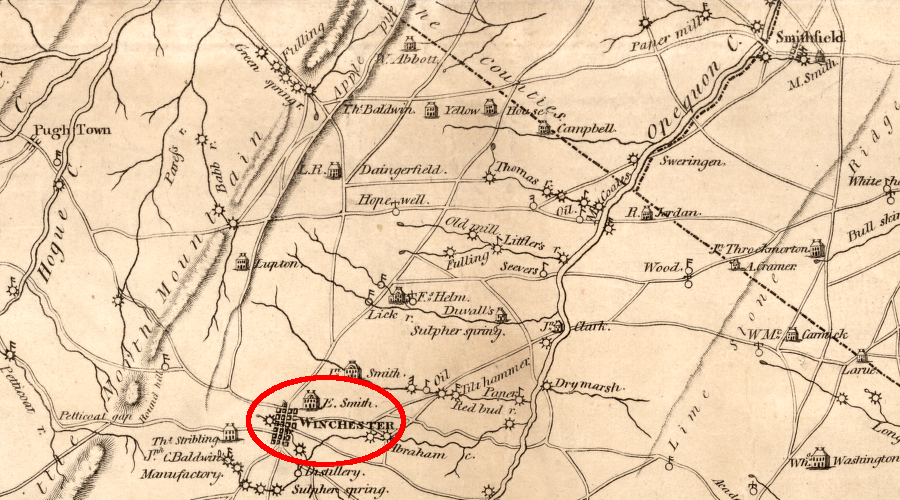

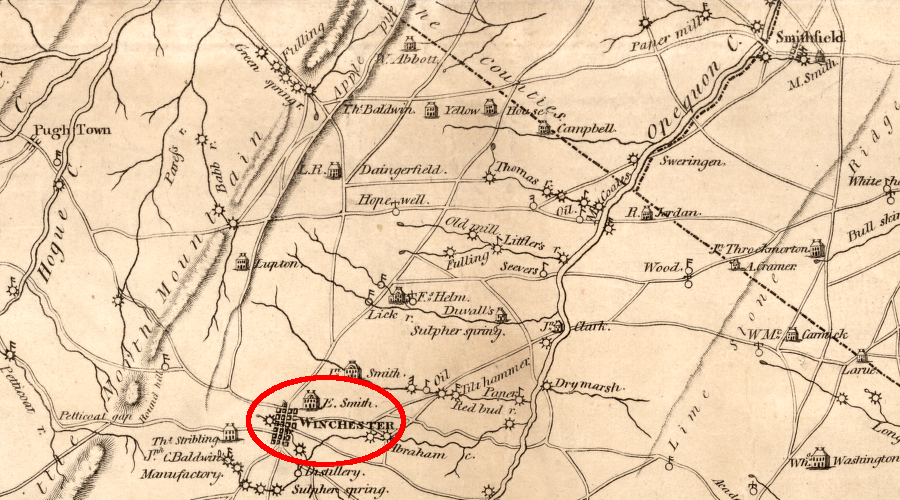

A Virginia court first referenced Judge Dillon's philosophy in 1882, when deciding a case involving the salary of a Petersburg city official. The Virginia Supreme Court has applied the Dillon Rule since 1896. For over a century, the rule has been cited in lawsuits filed in state courts in Virginia. The 1896 Virginia Supreme Court decision was triggered by a case involving the City of Winchester. The arsonist was caught, thanks to information provided by Mr. T. H. Redmond, but Winchester wanted to renege on its offer and keep its $500.

The Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals (as the state's highest court was known in 1896) determined that the city had no explicit authority from the General Assembly to pay a reward. Winchester got to keep its $500, and the City of Winchester v. Redmond decision established the Dillon Rule for Virginia courts:14

- A municipal corporation has no powers except those conferred upon it expressly or by fair implication by its charter, or the general laws of the State, and such other powers as are essential to the attainment and maintenance of its declared objects and purposes. It can do no act, make no contract, nor incur any liability that is not thus authorized. If it be even doubtful whether a given power has been conferred, the doubt must be resolved against the power.

the Virginia Supreme Court first used the Dillon Rule in 1896, to block Winchester (shown here in an 1809 map) from paying a reward for an arsonist

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Frederick, Berkeley, & Jefferson counties in the state of Virginia (1809)

The Dillon Rule was adopted by the Virginia Supreme Court 120 years after Virginia declared its independence and created its first constitution. The rule is based on case law, interpretations of the state constitution by state courts. The Dillon Rule was not based on a specific section in the 1869 state constitution that was in effect when the court ruled on the Winchester arson reward lawsuit, and is not encoded in a specific law passed by the General Assembly.

The Virginia Supreme Court did not violate the separation of powers and somehow create a new law when adopting the Dillon Rule. Instead, when the court cited the Iowa justice's rulings, it created the legal framework for interpreting the legality of the different laws passed by state and local governments.

The framework has empowered the General Assembly and limited the authority of local governments. Judge Dillon's legal philosophy was based on the assumption that local government was less competent and more corrupt than state government. However, that ignores the professionalization of local government since 1896. Professionalization was initiated in 1908 when the City of Staunton created the city-manager form of government. A general manager replaced 12 standing committees which had lacked accountability, and one person was given authority to allocate city resources in order to solve problems such as unpaved streets.15

The Virginia Supreme Court's 1896 decision kept power centralized in the state capital - but centralized authority has been traditional in Virginia from the beginning of colonization.

The first colonial government in Virginia was ruled by a private company with power centralized in London and implemented through the company's appointed leaders in Jamestown. The investors and the London Company's representatives in Virginia made decisions for the colony, even implementing martial law at one time.

Before 1619, colonists had no authority to create any form of local government with any powers separate from the company's authority. The representative assembly that met in 1619 was initiated by the company as part of its efforts to recruit more colonists, and the company's governor in Jamestown retained veto rights over any decisions made by that elected assembly.

After King James I revoked the company's corporate charter in 1624, and Virginia became a royal colony. Major policy decisions were still made in London by the king and his council rather than by private investors, or by the centralized colonial government in Jamestown.

All future kings and queens chose to perpetuate the representative assembly first created by the London Company in 1619, and authority for colonial government flowed from the sovereign down to that assembly. In the Virginia Resolves on the Stamp Act, adopted by the House of Burgesses in 1765, Virginia leaders who were upset over new taxes argued that the colony was accountable only to King George III. According to the Virginians (who ignored the shift in control to Parliament after King James II was deposed in the Glorious Revolution of 1688) only the sovereign had authority over Virginia; the General Assembly was independent of Parliament.16

Starting in 1634, the representative assembly created separate counties and parishes as population spread outward from Jamestown. Local government in Virginia has always been a tool for the legislature to manage its workload by delegating certain powers to local officials, who could make decisions that did not impact all of Virginia. In colonial times, three types of local government were created by the legislature: counties, towns (Jamestown, Williamsburg, and Norfolk), and Anglican parishes.

Local officials in counties, towns, and parishes dealt with local issues such as minor crimes, recordation of land deeds, definition of property boundaries, welfare for orphans and the poor, the selection of a minister, and tax rates to fund construction of churches, courthouses, and other local public buildings.

The General Assembly and governor kept control over local government by appointing all local officials in the counties. The colonial government that met in Jamestown until 1699, and in Williamsburg until 1780, appointed the justices on the county court (equivalent to modern county supervisors), sheriff, clerk of the court, etc.

After 1776, the new state government continued that pattern. Virginia's county officials were not elected by local voters; those officials were appointed by the governor and General Assembly. Voters within a county did not vote for their county officials until after 1851, when the state constitution was modified for the second time.17

Despite the appointment power of colonial/state officials, local governments did acquire significant independence starting in the 1600's. The local gentry in county courts established sufficient control to block efforts by Governor Berkeley and the House of Burgesses in the early 1670's to force county governments and vestries to lower tax rates. Discontent over those rates, and how the revenue was spent to reward the local gentry, was a factor in the 1676 uprising known as Bacon's Rebellion. The statehouse in Jamestown was burned, and Governor Berkeley was forced to flee to the Eastern Shore.18

local officials kept tax rates high in the mid-1600's, and in 1676 frustrated colonists ultimately rebelled and burned the three-part statehouse in Jamestown

Source: National Park Service, America's Oldest Legislative Assembly

and Its Jamestown Statehouse

The conversion from colony to state in 1776 led to the disestablishment of the Anglican church and the end of the vestry's power to tax the general public. Local county governments were given responsibilities for welfare services, but remained subordinate to the state government in Richmond. Independence from England did not lead to decentralization of the authority in the capital of Virginia.

There never was a ratification process by local governments to create the "state" of Virginia or adopt a Virginia constitution. Local governments have been subordinate to colonial and state authority based in Jamestown, Williamsburg, and Richmond since the first eight counties were created by the representative assembly in 1634.

From the beginning, power has flowed from the "top down" to local governments within Virginia, and not from the "bottom up." Even time the General Assembly meets in Richmond, state legislators are asked by lobbyists, local officials, and interest groups to alter some restriction on local government. State legislators may appreciate the attention they get, and the associated campaign support in some cases, but the Dillon Rule often frustrates local officials in urban areas of Virginia.

Evolving interpretations by the state courts on strict interpretation of the Dillon Rule have been a factor in key judicial decisions. Because the Dillon Rule is a judicial philosophy used by the state courts in Virginia and is not based on a specific state law, legal interpretations vary on when it should be applied.

In 2002, the Attorney General issued an opinion that the Fairfax County School Board could not expand its nondiscrimination policy to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation. In 2015, a different Attorney General ruled that local school boards did have such authority; the restrictive Dillon Rule did not block the school board and it could act to protect students, faculty, and staff from sexual-orientation and gender-identity discrimination.19

The impacts of suburban sprawl after World War II spurred local governments to steer or block development of housing units on private land. Those efforts triggered a significant number of lawsuits over the extent of local authority to control land use, and state court rulings on strict application of the Dillon Rule shifted between the 1950's and the 1980's.

In the 1950's and 1960's, state courts routinely blocked efforts by Fairfax County to rezone property to lower density. The county rezoned land in the western part of the county, with plans to delay growth in that region. Fairfax expected to prioritize its funding and build schools, roads, and other public facilities first in the fast-growing eastern part. When landowners sued the county, state judges overturned the rezoning in the Carper decision, claiming the county had exceeded the zoning authority granted by the General Assembly.

As major revisions in the state constitution were being drafted in 1971, local officials objected to proposals to drop the Dillon Rule and give jurisdictions with more than 25,000 people home rule authority. The Virginia Municipal League and the Virginia Association of Counties thought the state legislature was being responsive to their concerns. They feared that the General Assembly would adopt a pattern of passing special legislation that blocked local governments from specific acts. They thought local government would benefit by leaving the Dillon Rule untouched, and getting whatever authorities would be needed by special legislation.

In the 1970's, however, local officials realized they had miscalculated. State courts used the Dillon Rule to prevent Fairfax County from limiting the pace of development by imposing a moratorium on connections ("hookups") to the sewer system, or by phasing growth based on the availability of adequate public facilities. The strict interpretation of the power of local government to shape land use limited the county's flexibility to deal with suburban development and transportation issues.20

In 1985, the Fairfax Circuit Court finally empowered Fairfax County officials in the Aldre Properties, Inc. v. Board of Supervisors decision, and approved the downzoning of 41,000 acres near the Occoquan Reservoir. Today, state courts acknowledge the authority of local governments to adopt zoning ordinances that lower potential development density, and require "proffers" from developers before approving rezonings.21

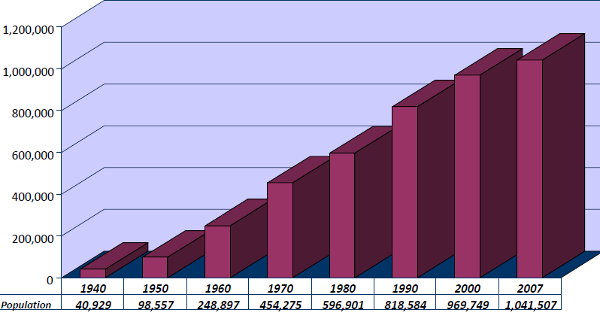

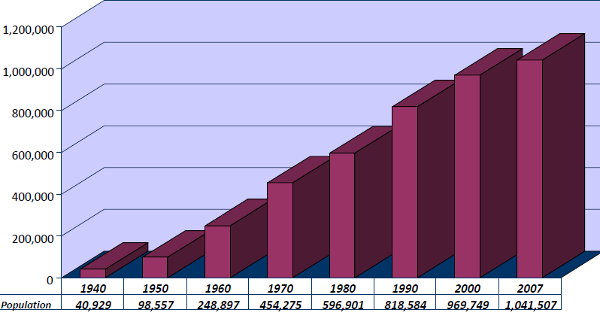

population grew in Fairfax County faster than government agencies could build new sewer, school, road, and other facilities for several decades, finally spurring a looser interpretation of the Dillon Rule by state courts so local governments could control development through zoning

Source: Fairfax County Planning Commission, A Look Back: 1938-2008

If Virginia were more of a Home Rule state and relied less upon the Dillon Rule, some suburban jurisdictions might chose to limit new development on private parcels until adequate public facilities are available.

Once a county/city/town zones a parcel for a certain level of development, the landowner has the "vested right" to build even if the new residents will overload local schools, roads, jails, etc. Rezoning land to higher density (upzoning) benefits the landowner by increasing the potential value of the property, while downzoning reduces the speculative value of private property.

The political pressure on local officials is almost always from landowners and developers who seek to increase the value of a parcel by upzoning. The political costs of downzoning private property are high, affecting campaign contributions to candidates for local offices.

Local governments have abandoned the option of downzoning and will issue building permits for projects consistent with local zoning (by right. When local school boards then buy more trailers to squeeze additional students into buildings, the common explanation by local officials is to cite the Dillon Rule - limiting planned development until adequate public facilities are available might be popular, but is not within the authority of local governments.

The Virginia General Assembly still has not granted towns/cities/counties the authority to require adequate public facilities before rezoning a parcel. Virginia courts have granted greater flexibility to local governments to manage land use, but the courts will not bend their interpretation of the Dillon Rule to permit local governments to require adequate public utilities. Only the state legislators can impose that requirement.

Back in 1969, the Commission on Constitutional Revision recommended Virginia switch from being a Dillon Rule state and become a Home Rule state. The draft language was:22

- ...a charter county or a city may exercise any power or perform any function which is not denied to it by this Constitution, by its charter, or by laws enacted by the General Assembly

If the language had remained the amendments submitted to the voters, then changing the Dillon Rule used by the Virginia courts would have occurred by voter approval of a new constitution with language making the switch. However, the General Assembly rejected the recommendation; home rule authority was not included in the language which voters approved to create the 1971 constitution.

At the time, desegregation was a particularly controversial issue in Virginia. Prince Edward County had closed its schools for four years in violation of the state constitution's requirement to provide a public education system. By not specifically repealing the Dillon Rule framework, the advocates for a new state constitution minimized debate regarding transfer of authority from state to local officials,

Since 1970, few suburbanizing areas have sought to alter the Dillon Rule. The solution to constraints on local control does not have to be switching from a Dillon Rule state to a Home Rule state.

Instead, local officials have sought special legislation from the General Assembly to address their particular concerns. That one-at-a-time approach has been so successful that Virginia has been described as operating under "legislative home rule." In 2015, the Hampton Roads Chamber of Commerce reaffirmed the conclusion of a 1999 task force. Once again, it endorsed retaining the Dillon Rule:23

- From an economic development standpoint, it creates an even playing field and stability... It makes up the pro business environment and the low tax environment, and the predictability of the government... Otherwise the tax rate would vary so much that businesses would be challenged.

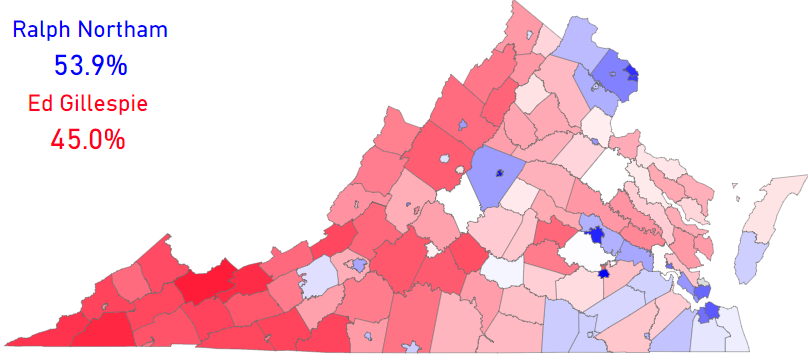

The Dillon Rule also has a political impact. The state has voted for relatively conservative officials since the Democrats defeated the Readjusters in the 1883 election. Those officials were Democrats for the next nine decades, but increasingly the Republican party offered the more-conservative candidates after the state parties finally aligned with the national parties in 1973.

The state shifted from reliably "red" to "purple" after the 2004 elections. Virginia noted for George Bush in 2004, but for Barrack Obama in 2008. In recognition of the shift, Governor Tim Kaine declared "Old Virginny is dead!"

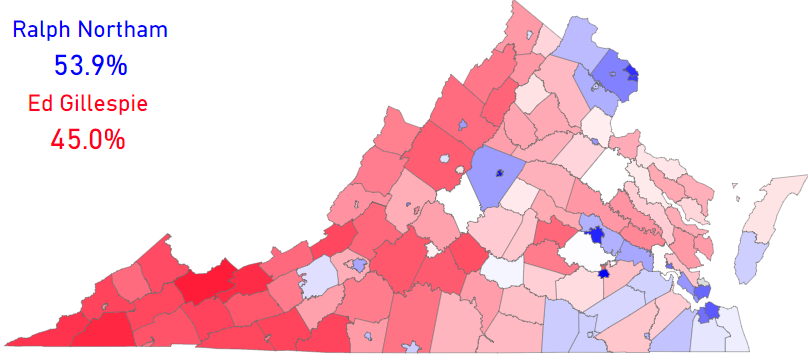

In the 2017 election, rural areas in the state continued to vote for Republican candidates but were swamped by Democratic votes in the urban and suburban area. A wave of Democratic candidates defeated Republican incumbents in House of Delegates races, and all statewide offices were held by Democrats. Conservative bloggers began to ask "Is Virginia Now a Blue State?"24

The threat to the rural areas is that tax, transportation, education, and other key issues are dominated by the state government. If the General Assembly and the governor (whether Republican or Democratic) support policies preferred by urban/suburban voters, there is no "home rule" option for rural jurisdictions to choose another path that reflects local preferences

Setting property tax rates is a local power in Virginia, so rural counties and small cities do have the authority to set low tax rates on real estate and personal property. Jurisdictions with low tax rates fund programs at lower levels, though they must meet whatever minimum levels of service are imposed by state requirements.

Local jurisdictions with a strong commitment to public services have the flexibility under the Dillon Rule to set higher property tax rates and provide expanded services. Local governments demonstrate their priorities and local powers when funding local schools. The quality and breadth of programs offered in urban/suburban areas such as Northern Virginia contrasts clearly with school services in rural counties, such as those in Southside and Southwest Virginia.

The General Assembly has granted local jurisdictions only a few local options. Local school districts still had to obtain state permission to start the school year before Labor Day, until the 2019 General Assembly relaxed the limitation. Thanks to the Dillon Rule, all jurisdictions must follow the statewide Standards of Learning for schools, SmartScale rankings for transportation projects, and other key policies issued from Richmond.

the 2017 election for governor demonstrated how Democratic urban/suburban voters (blue) can overwhelm the Republican (red) majorities in rural areas

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, Virginia's Gubernatorial Voting, 1961-2017

The most dramatic application of the power of the General Assembly to require statewide compliance with a controversial policy was in the 1956, after the US Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that schools must be desegregated. The Byrd Organization feared that school boards in some jurisdictions would prefer to comply with the court decision in order to keep the public schools open.

The Gray Commission proposed a plan in 1955 that included a local option component. A jurisdiction could chose to allow some black students to attend previously all-white schools, creating at least token levels of desegregation.

To block that possibility, in 1956 Governor Stanley and General Assembly created a pupil placement process controlled at the state level and required the closure of schools at risk of being integrated by local option or court order. The House of Delegates voted 59-39 to prevent local option, and the State Senate eliminated it 21-17. Approval by the state legislature of the Stanley Plan to block desegregation made any vote by a local school board completely irrelevant.

The Arlington School Board had agreed to start desegregation of its schools in 1956. To ensure that did not occur, the General Assembly also passed new legislation that eliminated local elections for the school board and transferred to the county supervisors the responsibility to appoint school board members.

Mills Godwin, a key leader in the plan to ensure statewide consistency in Massive Resistance and later elected governor twice, said:25

- I am convinced we should not pass any State law which would permit integration even in those localities where some may desire it.

In 1969, Mills Godwin was governor and he supported giving local government more authority. Gov. Godwin appointed 11 members to a Commission on Constitutional Revision, and the commission proposed increasing the power of local government:26

- All cities and those counties over 25,000 population would be able to adopt and amend their own charters and to exercise all powers not denied them by the Constitution, their charters, or statutes enacted by the General Assembly.

The proposed change would have transferred power away from members of the State Senate and House of Delegates to members of city councils and boards of supervisors in counties. The legislators in the General Assembly declined to endorse it. Because the proposed shift was not included in amendments passed by the General Assembly, Virginia's voters never got an opportunity to indicate their preference. Had a constitutional convention been called, legislators would have had less control over what changes in state/local authority might have been included in a completely new constitution and the Dillon Rule might have been modified.

Between 1975-1992, four commissions re-examined the relationship of state and local government - the 1975 Commission on City-County Relations (Stuart Commission), 1978 Commission on State Aid to Localities and Joint Subcommittee on Annexation (Michie Commission), 1990 Commission on Local Government Structure and Relationships (Grayson Commission), and 1992 Governor’s Advisory Commission on the Dillon Rule and Local Government. No changes were made to the Dillon Rule as a result of all the discussion.

Complaining about the Dillon Rule may be a standard practice for local officials who use it as a scapegoat. As noted in one assessment of the issue:27

- Faced with all the problems of governing, local officials sometimes need an excuse for why they cannot get things done. There may even be instances where crying Dillon may be disingenuous - where local officials hide behind Dillon to explain why they have not done what they did not want to do in the first place. Judge Dillon becomes the whipping boy for the troubles of local government.

Thanks to the Dillon Rule and the process of defining limited authority in charters for cities, state legislators still have political powers that frustrate local officials. For example, in 2019, the Charlottesville City Council wanted to raise its $18,000/year salaries and the $20,000/year salary for the mayor. That required a revision in the charter for the city, which was issued by the General Assembly to create the municipal corporation of Charlottesville.

The two members of the House of Delegates who represented the city, David J. Toscano and Rob Bell, were from opposite political parties but both opposed the modification of the city's charter. They declined to introduce the proposal in the General Assembly, and no other member of the House of Delegates was interested in challenging them. The fact that the city council's pay was controlled by the two state legislators made clear where political power still resides in Virginia.28

As the seriousness of the COVID-19 pandemic became more clear in March, 2020, Arlington County wanted to order restaurants to close in order to minimize transmission of the coronavirus. However, the County Board lacked the authority; only the state government had that power. Section 35.1-14 of the Code of Virginia gave the State Board of Health, not locally-elected officials, the authority to develop regulations for the safe operation of restaurants.

Retaining authority at the state level ensured all restaurants in Virginia had a common set of rules to follow. However, statewide consistency limited the ability of Arlington County to respond quicker to the threat than rural jurisdictions with fewer international travelers and less risk of COVID-19 transmission. County officials were only able to beg private establishments to close in a message issued on March 16, 2020:29

- States across the country, including Washington, DC and Maryland, have ordered all bars and restaurants to close for dine-in service as of 10:00 p.m. tonight (March 16, 2020). Arlington County does not have the legal authority to order the same...

- ...We thank all those that have already done so, but we plead with all our bars and restaurants that have NOT yet closed their dining rooms to do so as of 10:00 p.m. tonight (March 16).

The county's message was distributed one day before Governor Northam declared a public health emergency and began to establish enforceable limits on public gatherings, leading to a stay-at-home order on March 30.30

The state legislature's dominant authority over local government was revealed most clearly in 2021. The General Assembly debated whether all municipal elections should be moved to November, to coincide with elections for state and Federal offices.

At the time, 44% of the 38 cities and 57% of the 191 town held elections for local officials in May. That timing allowed candidates to focus on local issues such as property taxes rather than Social Security, and to gain attention without having to compete with more-partisan state and Federal elections. Turnout for May elections was traditionally lower, since the candidates rather than political parties shouldered most of the get-out-the-vote burden.

The number of voters casting ballots in Town of Blacksburg doubled after elections were moved to November in 2009. Democratic Party leaders in the City of Manassas recognized that they attracted more Democratic voters to the polls in November, especially every four years during presidential campaigns. After the city switched to holding municipal elections in November, the Democrats were more successful in electing candidates to City Council and as Mayor. Democrats in control of the General Assembly in 2021 were the primary advocates for mandating the same switch for all local elections.

Since Virginia operated under the Dillon Rule rather than home rule for local government, the decision of the legislature was final. Local officials still objected. The Coalition of Loudoun Towns stated:31

- The decisions at the local level - and the choice of who to lead the local governing body - should remain separate and distinct from the major issues of state and federal policy.

The Virginia Attorney General cited the Dillon Rule in 2024 to block a new Hopewell City Council ordinance, which required city employees who might be elected to City Council to resign any city job they might hold. Since City Council pay was minimal, the ordinance would deter city employees from running for local office. The ordinance may have been triggered because a city firefighter was running in the November election.

Some city charters issued by the General Assembly empowered the city council to pass such an ordinance, but that authorization language was not in Hopewell's charter. The Attorney General's opinion said:32

- ...it is my opinion that the City of Hopewell lacks the authority to adopt the specific ordinance provisions presented. The authority to enact such measures, or to authorize the Hopewell City Council to do so, lies with the General Assembly.

until the governor declared a public health emergency and issued Executive Orders limiting public gatherings, local officials could only beg local businesses to apply social distancing guidelines

Source: Governor of Virginia, Executive Order No. 55 (March 30, 2020)

Links

References

1. "Keam effort to give towns more options for raising funds dies," InsideNOVA, February 4, 2015, http://www.insidenova.com/news/crime_police/fairfax/keam-effort-to-give-towns-more-options-for-raising-funds/article_12ec7b0e-ad39-11e4-9a81-ef19536b32d1.html; "Va. panel axes bills allowing pre-Labor Day school start," The Virginian-Pilot, February 5, 2015, http://hamptonroads.com/2015/02/va-panel-axes-bills-allowing-prelabor-day-school-start; "The Short Leash," Henrico Monthly, June 2014, http://www.henricomonthly.com/interview/the-short-leash; Sarah Miller, "Virginia is for (Lovers) Business Owners who Feel the Human Rights Commission Poses a Threat to Their Religious Liberties," William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law, Volume 14, Issue 3, 2008, http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl/vol14/iss3/7; "AG office: Local control over Va. uranium mining limited," The Virginian-Pilot, October 13, 2013, http://hamptonroads.com/2013/10/ag-office-local-control-over-va-uranium-mining-limited; "Hope measure on auditor clears state Senate unanimously," InsideNOVA, February 23, 2015, http://www.insidenova.com/news/arlington/hope-measure-on-auditor-clears-state-senate-unanimously/article_8fedf87c-bb57-11e4-a199-63197948def7.html; "New Va. law would permit Arlington to make amphitheater smoke-free," InsideNOVA, February 27, 2019, https://www.insidenova.com/news/arlington/new-va-law-would-permit-arlington-to-make-amphitheater-smoke/article_8df1327c-3a9d-11e9-805a-7b3637c28396.html; "An Act to amend and reenact § 15.2-2119.2 of the Code of Virginia, relating to discounted water and sewer fees," HB 1585, Virginia General Assembly, 2020, http://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?201+ful+HB1585ER; "Northam signs bill allowing town of Altavista to offer discounted rates on water, sewer," News & Advance, March 14, 2020, https://www.newsadvance.com/news/local/northam-signs-bill-allowing-town-of-altavista-to-offer-discounted/article_5e958b2d-72c3-546f-9b56-568dd5d90fbe.html; "Schapiro: Va.'s Constitution - 50 years young," Richmond Times-Dispatch, February 17, 2021, https://richmond.com/news/state-and-regional/govt-and-politics/schapiro-va-s-constitution-50-years-young/article_6c7f578f-87c4-5b7e-afa1-c06507477c23.html (last checked February 18, 2021)

2. "Fairfax County Rejects Meals Tax," WRC, November 7, 2016, https://www.nbcwashington.com/news/local/fairfax-county-meals-tax-vote/96057/; "New Democratic majority in Richmond wrests money, power for Northern Virginia from downstate," Washington Post, March 16, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/new-democratic-majority-in-richmond-wrests-money-power-for-northern-virginia-from-downstate/2020/03/15/e287aafa-64cc-11ea-acca-80c22bbee96f_story.html (last checked March 16, 2020)

3. "Virginia Decoded," Code of Virginia, https://vacode.org/15.2-2159/; House Bill No. 785 (HB 785), Virginia General Assembly, 2020, https://leg1.state.va.us/cgi-bin/legp504.exe?201+ful+HB785H3; "Bill maneuver on trash fee met with controversy from Pittsylvania County board," Danville Register & Bee, March 14, 2016, http://www.godanriver.com/news/pittsylvania_county/bill-maneuver-on-trash-fee-met-with-controversy-from-pittsylvania/article_9b97ed74-ea3e-11e5-a43b-53dbc7aef9d7.html, "Solid waste fee gets trashed by board," Danville Register & Bee, October 5, 2015, http://www.godanriver.com/news/pittsylvania_county/solid-waste-fee-gets-trashed-by-board/article_faa1f004-6bcb-11e5-ba45-db0f394cbd48.html, "Supervisors seek state approval to change solid waste fee for some," Danville Register & Bee, November 20, 2012, http://www.newsadvance.com/go_dan_river/news/pittsylvania_county/supervisors-seek-state-approval-to-change-solid-waste-fee-for/article_34706614-3383-11e2-babf-001a4bcf6878.html (last checked March 15, 2016)

4. "Va. House effectively kills bill moving Herndon elections from spring to fall," Washington Post, February 20, 2015, http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/va-house-effectively-kills-bill-moving-herndon-elections-from-spring-to-fall/2015/02/20/cf69ff82-b878-11e4-a200-c008a01a6692_story.html; "Herndon changes election date after similar effort failed in Richmond," Washington Post, March 11, 2015, http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/herndon-changes-election-date-after-similar-effort-failed-in-richmond/2015/03/11/a76e7af6-c801-11e4-aa1a-86135599fb0f_story.html; "SB 1157 Municipal elections; shifting elections to November," 2021 Special Session 1, Virginia General Assembly, https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?212+sum+SB1157 (last checked March 13, 2021)

5. "Alexandria to take up its Confederate memorials tonight," The Washington Post, September 8, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/alexandria-to-take-up-its-confederate-memorials-at-council-tonight/2015/09/08/4f02bc0c-562b-11e5-b8c9-944725fcd3b9_story.html; "Portsmouth seeking court order to remove Confederate monument," The Virginian-Pilot, August 27, 2015, http://pilotonline.com/news/government/local/portsmouth-seeking-court-order-to-remove-confederate-monument/article_4d79c94c-913c-5c15-8abf-5b36748c7ccb.html; "Alexandria renames Jefferson Davis Highway to Richmond Highway," Washington Post, June 23, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/alexandria-renames-jefferson-davis-highway-to-richmond-highway/2018/06/23/a1af93c0-76fe-11e8-b4b7-308400242c2e_story.html; "Arlington may soon be able to change name of Jefferson Davis Highway," Washington Business Journal, March 25, 2019, https://www.bizjournals.com/washington/news/2019/03/25/arlington-may-soon-be-able-to-change-name-of.html; "Official Opinion 19-010," letter from Attorney General Mark Herring to Honorable Mark H. Levine, March 21, 2019, https://www.oag.state.va.us/files/opinions/2019/19-010-Levine-issued.pdf; "General Assembly mandates renaming of Jefferson Davis Highway," Chesterfield Observer, March 10, 2021, https://www.chesterfieldobserver.com/articles/general-assembly-mandates-renaming-of-jefferson-davis-highway/ (last checked March 13, 2021)

6. "Momentum to Remove Confederate Symbols Slows or Stops," New York Times, March 13, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/14/us/momentum-to-remove-confederate-symbols-slows-or-stops.html; "Confederate flag will not return to grounds of Sutherlin Mansion," Danville Register & Bee, October 29, 2015, http://www.godanriver.com/news/danville/confederate-flag-will-not-return-to-grounds-of-sutherlin-mansion/article_92755d40-7e59-11e5-86a1-b37da377287d.html; "Opinion 15-050," August 6, 2015, Virginia Attorney General, http://ag.virginia.gov/files/Opinions/2015/15-050_Whitfield.pdf; "Governor Vetoes Legislation Restricting Local Authority to Remove or Modify Monuments or Memorials - See more at: http://governor.virginia.gov/newsroom/newsarticle?articleId=14561#sthash.ToJPF3T7.dpuf," Governor of Virginia Newsroom, March 10, 2016, http://governor.virginia.gov/newsroom/newsarticle?articleId=14561 (last checked March 15, 2016)

7. "HB 1537 War memorials for veterans; removal, relocation, etc.," Virginia Legislative Information System, Virginia General Assembly, 2020 Session, https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?201+ful+HB1537ER (last checked April 13, 2020)

8. "Botetourt County School Board approves superintendent's contract," The Roanoke Times, October 8, 2015, http://www.roanoke.com/news/virginia/botetourt-county-school-board-approves-superintendent-s-contract/article_22900923-6301-53fc-bbec-63f42057ced0.html; "Local superintendents demand impressive perks," WJLA, May 13, 2015, http://wjla.com/features/7-on-your-side/local-superintendents-demand-impressive-perks-113942; "Making Sense of Va. School-Year Calendar," Washington Post, October 7, 2004, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A11932-2004Oct6.html; "Section 22.1-79.1. Opening of the school year; approvals for certain alternative schedules," Code of Virginia, http://leg1.state.va.us/cgi-bin/legp504.exe?000+cod+22.1-79.1 (last checked February 20, 2015)

9. "Virginia closer to allowing schools to start before Labor Day," Daily Press, February 12, 2019, https://www.dailypress.com/news/education/community/dp-nws-virginia-schools-open-labor-day-0212-story.html (last checked February 14, 2019)

10. "Municipal Corporation," West's Encyclopedia of American Law, 2005, published on Encyclopedia.com, http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3437703005.html; "Local Government Authority," National League of Cities, http://www.nlc.org/build-skills-and-networks/resources/cities-101/city-powers/local-government-authority (last checked February 17, 2015)

11. "Chapter 5 - The Dillon Rule and Its Limitations on a Locality's Land Use Powers," Albemarle County Land Use Law Handbook, March 2014, Section 5-300, Section 5-410, http://www.albemarle.org/department.asp?department=ctyatty&relpage=3190 (last checked February 18, 2015)

12. "Chapter 5 - The Dillon Rule and Its Limitations on a Locality's Land Use Powers," Albemarle County Land Use Law Handbook, March 2014, Section 5-510, http://www.albemarle.org/department.asp?department=ctyatty&relpage=3190 (last checked February 18, 2015)

13. Jesse J. Richardson, Jr., Meghan Zimmerman Gough, Robert Puentes, "Is Home Rule The Answer? Clarifying The Influence Of Dillon's Rule On Growth Management," Brookings Institution, January 2003, p.1, http://www.brookings.edu/research/reports/2003/01/01metropolitanpolicy-richardson; City of Winchester v. Redmond, November 19, 1896, Reports of Cases in the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia: Volume 93, p.714, https://books.google.com/books?id=RTgTAAAAYAAJ; Raben M. deVoursney, "The Dillon Rule in Virginia: Whats Broken? What Needs to be Fixed?," University of Virginia News Letter, Volume 68, Number 7 (July/August 1992), https://newsletter.coopercenter.org/sites/newsletter/files/Virginia_News_Letter_1992_Vol._68_No._7.pdf (last checked May 3, 2022)

14. "The Short Leash," Henrico Monthly, June 2014, http://www.henricomonthly.com/interview/the-short-leash; City of Winchester v. Redmond, November 19, 1896, Reports of Cases in the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia: Volume 93, p.711, https://books.google.com/books?id=RTgTAAAAYAAJ; "Curious Commonwealth asks: Why is Virginia a Dillon Rule state?," Virginia Public Media, March 5, 2025, https://www.vpm.org/news/2025-03-05/curious-commonwealth-john-dillon-rule-virginia-locality-law-why (last checked July 17, 2025)

15. Clay L. Wirt, "Dillon's Rule," Virginia Town and City, Volume 24, Number 8 (August 1989), online at http://578125292684560794.weebly.com/uploads/3/7/7/1/37714259/dillon_rule_article.pdf; Mayor William A. Grubert, "The Origin of the City Manager Plan in Staunton, Virginia," City of Staunton, 1954, https://www.icmaml.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Origin-City-Manager-Plan-in-Staunton-VA.pdf (last checked June 15, 2019)

16. "Virginia Stamp Act Resolutions," 1765, Colonial Williamsburg, http://www.history.org/history/teaching/tchcrvar.cfm (last checked February 18, 2015)

17. Brent Tartar, The Grandeees of Government: the Origins and Persistence of Undemocratic Politics in Virginia, University of Virginia Press, 2013, p.190

18. Brent Tartar, "Bacon's Rebellion, the Grievances of the People, and the Political Culture of Seventeenth-Century Virginia," Virginia Magazine of History & Biography, Volume 119 Issue 1, 2011, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41059478 (last checked February 18, 2015)

19. "Va. school boards' anti-discrimination stands can mention sexual orientation," Washington Post, March 4, 2015, http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/va-school-boards-anti-discrimination-policies-can-include-sexual-orientation/2015/03/04/b72a2f88-c2a4-11e4-ad5c-3b8ce89f1b89_story.html; "2002 Official Opinions: 02-029," Virginia Attorney General Jerry Kilgore, April 30, 2002, http://www.oag.state.va.us/index.php/citizen-resources/opinions?id=73#april; "2015 Official Opinions: 14-080," Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring, March 4, 2015, http://www.oag.state.va.us/index.php/citizen-resources/opinions?id=422 (last checked March 5, 2015)

20. Board of Supervisors v. Carper, Virginia Supreme Court, 200 Va. 653 (1959), http://law.justia.com/cases/virginia/supreme-court/1959/4865-1.html; Lucille Harrigan, Alexander von Hoffman, "Happy to Grow: Development and Planning in Fairfax County, Virginia," Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University, February 2004, p.14, http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/jchs.harvard.edu/files/w04-2_von_hoffman.pdf (last checked February 18, 2015)

21. Grayson P. Hanes, J. Randall Minchew, "On Vested Rights to Land Use and Development," Washington and Lee Law Review, Volume 46, Issue 2 (March 1, 1989), p.392, http://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol46/iss2/3/; Clay L. Wirt, "Dillon's Rule," Virginia Town and City, Volume 24, Number 8 (August 1989), online at http://578125292684560794.weebly.com/uploads/3/7/7/1/37714259/dillon_rule_article.pdf (last checked June 14, 2019)

22. Richard Schragger, C. Alex Retzloff, "The Failure of Home Rule Reform in Virginia: Race, Localism, and the Constitution of 1971," Virginia Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 2020-35 in Essays on the Constitution of Virginia, University of Virginia Press, 2021, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3574765 (last checked December 25, 2022)

23. Jesse J. Richardson Jr., "Sprawl in Virginia: Is Dillon the Villain?," Virginia Issues and Answers, Volume 7, Number 1 (Spring 2000), http://www.via.vt.edu/spring00/vasprawl.html; "Task Force on the Dillon Rule," Hampton Roads Chamber Of Commerce, May 12, 1999, http://fhrinc.org/the-dillon-rule/the-dillon-rule-in-virginia; "Dillon Rule has friends and foes," Inside Business - The Hampton Roads Business Journal, February 13, 2015, http://insidebiz.com/node/439351; Raben M. deVoursney, "The Dillon Rule in Virginia: Whats Broken? What Needs to be Fixed?," University of Virginia News Letter, Volume 68, Number 7 (July/August 1992), https://newsletter.coopercenter.org/sites/newsletter/files/Virginia_News_Letter_1992_Vol._68_No._7.pdf; "Curious Commonwealth asks: Why is Virginia a Dillon Rule state?," Virginia Public Media, March 5, 2025, https://www.vpm.org/news/2025-03-05/curious-commonwealth-john-dillon-rule-virginia-locality-law-why (last checked July 17, 2025)

24. "Is Virginia Now a Blue State?," Real Clear Politics, November 9, 2017, https://www.realclearpolitics.com/articles/2017/11/09/is_virginia_now_a_blue_state_135492.html

25. Matthew D. Lassiter, Andrew B. Lewis, The Moderates' Dilemma: Massive Resistance to School Desegregation in Virginia, University of Virginia Press, 1998, p.16, https://books.google.com/books?id=ps02K4GOQo0C; Peter Wallenstein, Cradle of America: Four Centuries of Virginia History, University Press of Kansas, 2007, pp.346-347, https://books.google.com/books/about/Cradle_of_America.html?id=mGd5AAAAMAAJ (last checked December 29, 2017)

26. A.E. Dick Howard, "Constitutional Revision: Virginia and the Nation," University of Richmond Law Review, Volume 9 Issue 1 (1974), p.5, p.44, https://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview/vol9/iss1/2 (last checked June 22, 2019)

27. Richard C. Schragger, C. Alex Retzlof, "The Failure of Home Rule Reform in Virginia: Race, Localism, and the Constitution Of 1971," Virginia Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 2020-35, in Essays on the Constitution of Virginia, University of Virginia Press, 2021, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3574765; Raben M. deVoursney, "The Dillon Rule in Virginia: Whats Broken? What Needs to be Fixed?," University of Virginia News Letter, Volume 68, Number 7 (July/August 1992), https://newsletter.coopercenter.org/sites/newsletter/files/Virginia_News_Letter_1992_Vol._68_No._7.pdf (last checked May 3, 2022)

28. "Toscano, Bell oppose city charter changes, likely dooming salary proposal," The Daily Progress, January 3, 2019, https://www.dailyprogress.com/news/local/city/toscano-bell-oppose-city-charter-changes-likely-dooming-salary-proposal/article_463f627c-0fb0-11e9-a2dc-abcb4f9febda.html (last checked January 7, 2019)

29. "Arlington County Pleads with Bars and Restaurants to Close Dining Rooms," Arlington County, March 16, 2020, https://newsroom.arlingtonva.us/release/arlington-county-pleads-with-bars-restaurants-to-close-dining-rooms/; "Without State Mandate, Northern Virginia Restaurants And Bars Face Tough Decision Whether To Close," WAMU, March 18, 2020, https://wamu.org/story/20/03/18/without-state-mandate-northern-virginia-restaurants-and-bars-face-tough-decision-whether-to-close/?_ga=2.69046039.722146454.1589285066-1047201017.1589285065 (last checked May 12, 2020)

30. "Order of the Governor and State Health Commissioner Declaration of Public Health Emergency," Office of the Governor, March 17, 2020, https://www.governor.virginia.gov/media/governorvirginiagov/governor-of-virginia/pdf/Order-of-the-Governor-and-State-Health-Commissioner-Declaration-of-Public-Health-Emergency.pdf; "Temporary Stay At Home Order Due To Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19)," Executive Order No. 55, Governor of Virginia, March 30, 2020, https://www.governor.virginia.gov/media/governorvirginiagov/executive-actions/EO-55-Temporary-Stay-at-Home-Order-Due-to-Novel-Coronavirus-(COVID-19).pdf (last checked May 12, 2020)

31. "Loudoun Mayors Oppose Moving Town Elections to November," LoudounNOW, February 3, 2021, https://loudounnow.com/2021/02/03/loudoun-mayors-oppose-moving-town-elections-to-november/; "Moving Municipal Elections to November Is a Good Decision," Bearing Drift, February 3, 2021, https://bearingdrift.com/2021/02/03/moving-municipal-elections-to-november-is-a-good-decision/ (last checked February 18, 2021)

32. "State AG says Hopewell does not have power to enact employees-on-council restriction," The Progress-Index, July 2, 2024, https://www.progress-index.com/story/news/2024/07/02/va-ag-says-hopewell-not-authorized-to-keep-employees-off-city-council/74279721007/; "Opinion 24-014,"Virginia Attorney General, July 1, 2014, https://www.oag.state.va.us/files/Opinions/2024/24-014-Coyner-issued.pdf (last checked July 3, 2024)

Virginia Government and Virginia Politics

Virginia Places