the first state constitution was written in Williamsburg, as the Fifth State Convention met in the Capitol

Source: Library of Virginia, First Virginia Constitution, June 29, 1776

the first state constitution was written in Williamsburg, as the Fifth State Convention met in the Capitol

Source: Library of Virginia, First Virginia Constitution, June 29, 1776

Prior to 1776, there was no written constitution establishing any limits on the power of colonial government in Virginia. There was no independent judiciary to counter the decisions of the governor, the Governor's Council, the House of Burgesses, the county courts, or the vestry of the Anglican parishes.

The leaders of the Virginia Company, particularly its Treasurer, sent guidance to Jamestown from 1607-1624. After the company's charter was revoked, the king's advisors in London sent royal instructions to the governor in Jamestown and then to Williamsburg to guide the governor's decisions.

Colonial governors did not share those instructions freely with the delegates elected to the House of Burgesses, and the power of the General Assembly was not limited by any written contract that colonists had ratified. Constraints on the power of the governor in the colony of Virginia were cultural and economic, not based on any written delineation of the powers of the office. The gentry, not words on paper, constrained the governor's authority. Rich landowners shipping tobacco to England generated enough tax revenue to have influence in London. The Virginia gentry managed to force several governors out of office, including Edmund Andros, Francis Nicholson, and Alexander Spotswood.

There was no legal document spelling out limits of government power which could be enforced by Virginians through any judicial process. In colonial Virginia, there was no constitution defining the role of the governor and no independent judiciary to invalidate any decisions by officials. The House of Burgesses, Council of State, and royal governor understood the concept of "separation of powers," but those were flexible. Authority was re-negotiated regularly and informally, as officials with different personalities occupied different positions.

Once, the average citizens reacted against the abuse of authority that was possible for appointed and elected officials. Bacon's Rebellion in 1676 was triggered in part by excessive taxes and exorbitant fees imposed by Governor Berkeley and the General Assembly. The governor had obtained support from key Virginia landowners in part by appointing them to various positions, and sometimes to multiple offices simultaneously. The House of Burgesses then passed tax and trade laws that provided excessive benefits to the governor, members of the Governor's Council, and some burgesses at the expense of all the other colonists.

Governor Berkeley also centralized authority by declining to call elections for a new House of Burgesses for 15 years. He retained what became known as the Long Assembly between 1661-1676. The average colonial farmers were forced to pay burdensome taxes to support the political elite. Without elections, the taxpayers lacked the ability to change government policy peacefully. The alternative was violent change, and the revolt is known as Bacon's Rebellion. It led to intervention by London officials and Governor Berkeley was forced from office, but no legally-enforceable document checked the powers of future governors and General Assemblies.

In the 1760's, royal governors became embroiled in the conflict between Parliament and the colonies. Parliament wanted revenue from America to help defray the costs of the French and Indian War. British troops and the navy won the war, and Parliament thought the colonists who benefitted should help pay for the military's expenses. To minimize future defense costs in North America, George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763. It was intended to limit conflict with Native Americans occupying the territory acquired from the French, but the colonists objected to officials in London blocking the profits from speculating in land and westward expansion.

Opposition to the powers of the king and Parliament led to philosophical debates about the social contract and the role of government. The "no taxation without representation" objections to Parliament's actions evolved into a fundamental belief that the structure of government in the colonies was fatally flawed. That discussion led to the American Revolution and the creation of a new form of government, later defined by Abraham Lincoln in the Gettysburg Address as "government of the people, by the people, for the people."1

Virginia started the process by writing the first Declaration of Rights and then the first state constitution, describing how a new form of government would replace colonial authority and eliminate the role of a monarch. Virginia became an independent state when it adopted its first state constitution in 1776. The constitution has been revised several times, but the Bill of Rights has been incorporated in each subsequent version.

The 1776 constitution was replaced in 1830. That document was ratified by the voters, as was its replacement in 1851.

During the Civil War, Virginia had two state governments. The Secession Convention met in Richmond in 1861 and drafted a new constitution, eliminating references to the United States of America and adding references to the Confederate States of America. The 1862 election date scheduled for ratification by the voters happened to occur when the Union armies were approaching Richmond in the Peninsula Campaign.

Few voters participated in the decision process, and a majority of those who went to the polls rejected the new constitution. The Confederate state government based in Richmond governed Virginia from 1861-65 under the 1830 state constitution that required the governor to be a "native citizen of the United States."2

That classification exposed both Civil War governors, John Letcher and William Smith, to charges of treason for levying war against the United States. Under Article III, Section 3 of the US Constitution, that charge requires the accused person to be a US citizen. A non-citizen can not be convicted of "treason" against the United States.

The former president of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis, was tried for treason in 1868 but the prosecution was not completed. Stopping his trial avoided the risk that a court might rule that secession was legal and thus Davis was not a US citizen when he organized the invasion of Maryland.3

A new constitution was adopted in 1902. It was designed to restrict the opportunity to vote to just white males. The US Supreme Court had made clear that states could evade the Fifteenth Amendment and its requirements for equal suffrage for black voters. The white elite used the new constitution to disfranchise most black voters, and many poor whites as well. The 1901-1902 general convention proclaimed the new constitution to be in effect without a ratification vote.

It was the last time Virginia has held a general constitutional convention. Conventions with limited authority, as approved by the voters, have proclaimed changes in 1945 related to how people in the military could vote and in 1956 on how the state could support private, racially-segregated schools.

Since the 1870 constitution created a process for incremental amendments, voters have modified different state constitutions in large and small ways. In 1928, a major rewrite of the constitution reduced the number of words by half and gave the government substantially more authority over the executive branch. That revision was done through the amendment process, rather than via a constitutional convention.

The last wholesale replacement of the state constitution was done in four amendments which were approved by the voters in 1971.

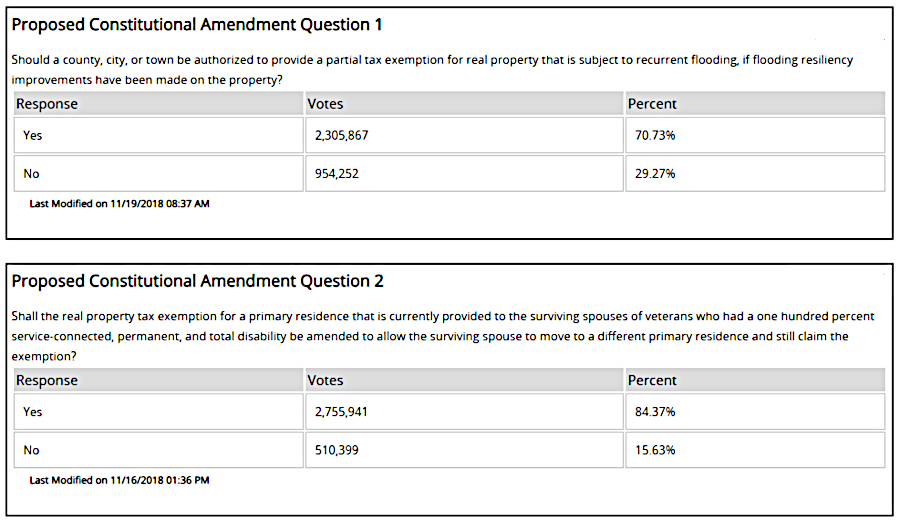

Nearly every General Assembly considers new proposals for additional revisions, but few make it through the process. Constitutional amendments must be approved twice by the General Assembly and an election for the House of Delegates must occur between those two votes, and then voters must approve the change in a statewide referendum. The most recent modifications occurred in 2018, when voters approved two amendments to authorize specific property tax exemptions, and in 2020 when voters approved creating a bipartisan commission to redraw boundaries of election districts after the Census every 10 years.4

the Constitution of Virginia was amended again in 2018

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, 2018 November General

Changes proclaimed by a constitutional convention, and amendments to the constitution approved by the voters, are by definition "constitutional." Excepting the US Constitution, the Constitution of Virginia is the highest law of the land within the boundaries of Virginia. Other laws passed by the state legislature or local governments must be consistent with the state and Federal constitutions.

Ultimately, the Virginia Supreme Court determines if a law passed by the General Assembly is consistent with the state constitution. State judges defer to the legislators, and rarely rule that a state law is void because it violates the state constitution. In contrast to the US Constitution which granted limited authority in 1788 to a new Federal government, the Virginia Constitution since 1776 has imposed limited restrictions on the broad general authority of the state government.

The State Corporation Commission once noted in a case:5

For example, the state courts, including the Supreme Court of Virginia, have declined to rule that the legislature's decisions on redistricting were unconstitutional.

In 2017 and 2018, state courts upheld the boundaries of five House of Delegates districts and six State Senate districts that had been redrawn in 2011 after the 2010 Census. Plaintiffs had argued that the boundaries violated the requirement in Article II, Section 6 of the Constitution of Virginia that districts be "composed of contiguous and compact territory."

At the same time, Federal courts were more willing to intervene. They forced revisions of the boundaries for legislative districts, after plaintiffs argued those boundaries violated separate Federal requirements.6

If Virginia Supreme Court invalidates a law, the General Assembly can accept the decision, revise the legislation so it will be consistent with the court's interpretation, or start the process to amend the constitution.

If a Federal court determines a state law violated the US Constitution, state legislators in the General Assembly does not have the option to revise the state constitution in order to restore the law's impact. The US Constitution, as interpreted by the US Supreme Court, overrides state constitutions.

For example, in 2006 Virginia voters approved the "marriage amendment" to the state constitution. That language modified the Bill of Rights for the second time since 1776. The first time occurred with the 1971 constitution. The phrase "therefore, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed" was added to Section 13. It now reads (emphasis added):7

The 2006 marriage amendment was designed to prevent a future General Assembly from authorizing same-sex marriage. The constraint is now void. In 2015, in a 5-4 decision by the US Supreme Court in Obergefell v. Hodges, state and Federal laws preventing same-sex marriage were defined as inconsistent with the US Constitution.

The marriage amendment remained a part of the Virginia constitution, but no state or Federal court can enforce the prohibition unless the US Supreme Court reverses Obergefell v. Hodges. To guarantee the right for same-sex marriage in Virginia, a future amendment or wholesale revision of the constitution will be required to revise the Bill of Rights again. An advocate for revising the state constitution, the executive director of Equality Virginia, argued in 2022:8

A bill to amend the state constitution to eliminate the marriage amendment was introduced in the 2024 session, after Democrats gained control of both the House of Delegates and the State Senate in the 2023 elections. The Senate Privileges and Elections Committee voted to carry over the bill until 2025. That was a routine maneuver, because the constitutional amendment had to be approved by members chosen in two separate general elections. To get a constitutional amendment on the ballot in 2026, the General Assembly members elected in 2023 and 2025 had to approve the same language.

The same maneuver was used for two other proposed constitutional amendments, to ensure access for abortions and to automatically restore voting rights to felons when they are released from upon release from incarceration.

Votes on those bills were expected to match closely the partisan balance in the legislature. Postponing votes on those bills until 2025 reflected an assumption that the narrow Democratic majorities, 21-19 in the State Senate and 51-49 in the House of Delegates, would still be in place in 2025. If one or more Democratic members died in office or resigned, a Republican replacement could alter the balance of power and block passage in 2025.

As an interim measure, the 2024 General Assembly passed a bill to alter the Code of Virginia. Only 5 of the 68 Republicans supported the measure. To the surprise of some observers, Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin signed rather than vetoed it.

Because the state constitution was still unchanged, a future General Assembly had the option to revise the new section that was added to the Code of Virginia:9

As expected, in 2025 the House of Delegates and the State Senate renewed the approval process for the three state constitution amendments. If passed again in 2026, voters would make the final decision on November 3, 2026. If they approved the amendment, the ban would have been included the Virginia constitution for 20 years but in effect for only eight years, due to the US Supreme Court's Obergefell v. Hodges decision in 2015.

The ban on same sex marriages had been approved in 2006 by a 57% majority, but the Democratic leaders in the legislature were confident that a majority of the voters would approve removing the now-invalid language. By 2023, all 38 cities and 94 of the state's 95 counties (all but Highland County) had at least one same-sex couple, according to Census data.

The proposed change was:10

The advocates for constitutional changes made a similar calculation regarding the proposed amendments regarding abortion and restoration of voting rights to felons who had completed their sentences. They expected voter approval on November 3, 2026.

A fourth constitutional amendment was approved by the General Assembly on October 31, 2025. The Democratic leaders called the 2024 special session back, a process which the Republican governor could not block, and voted on a proposed amendment to allow a one-time partisan redistricting of US House of Representative districts. That was a response to other states making partisan changes to their congressional district boundaries in 2025, in order to maintain Republican control of the US House of Representatives in the 2026 election.

However, a state judge ruled in January that the October vote was not valid. State law required advertising a proposed constitutional amendment "not later than three months prior to the next ensuing general election of members of the House of Delegates." The 2025 in-person voting day was November 4, so the General Assembly's vote on October 31 did not meet the requirement.

The ruling came just before the 2026 General Assembly was to pass a new law retroactively eliminating the requirement for three months notice, and to shift jurisdiction of the case to another judge. The ruling included emphatic language:11