Totero Town, recreated at Explore Park near Roanoke

Towns and cities don't just happen - there's no magical "poof" and a moment later they are there on the map. There are reasons that they develop, when they do and where they do.

Native American towns were almost always associated with agricultural fields. The basic assumption is that the bands of earliest Virginians travelled constantly from hunting camp to hunting camp, until adopting agriculture. It's logical to assume that the hunting camps became focal points for the plants used by the natives. Discarded seeds would regrow the following year, creating concentrations of the plants preferred by the natives. This pattern may have occurred first in Meso-America, with one particular grass selected over and over again until its small seedhead was converted into corn, and then adopted by tribes to the north and east. Prior to that, however, it's likely that the first Virginians were already concentrating in short-term communities at good fishing and shellfish collecting points in Tidewater.

After Europeans arrived, settlements continued to be dispersed as tobacco plantations for over a century. More than any other factor, transportation triggered the development and growth of most Virginia cities. Where rivers were no longer navigable, Fall Line cities developed. Where rail lines intersected, Manassas and Roanoke developed. Rarely was transportation not an issue in determining where groups of people would congregate (and rarely was it the only factor).

Political decisions have stimulated or hindered urban growth since the first colonists sailed 60 miles upstream beyond Cape Henry, to a deep water anchorage on the north bank of what they named the James River. The Roanoke Colony was located on the coastline in 1585, but 22 years later the English knew to start their settlement far inland - to minimize the dangers from the Spanish and other international enemies.

Norfolk was never the state capital, though it had the best harbor for trade and was once the largest city in Virginia. Norfolk was too exposed to international threat, and just 60 years ago enemy warships (German U-boats) were sinking American ships off the coastline of Virginia Beach.

The same security concerns that prevented Norfolk from becoming the capital triggered the move of the capital to Richmond in 1780. That political decision left Williamsburg so economically stagnant that many colonial structures remained intact 150 years later when John D. Rockefeller first began to fund restoration of Colonial Williamsburg.

Today, smart growth advocates contend the issues of sprawl and regional growth are tightly connected to political decisions on funding highways, rail, and airport transportation improvements. Many politicians and voters seem unfamiliar with the relationship, however. In political campaigns throughout Virginia, campaigns focus on how a candidate will "get more money from Richmond/Washington" for local transportation projects. The assumption is that "more roads/transit" is the basic solution, and the best answer is to increase the supply of transportation infrastructure (preferably funded by others). Few candidates discuss how local county/city/town decisions, on where to approve new subdivisions and shopping centers, will shape the demand for new transportation infrastructure.

Since the 1800's, Virginians have been able to alter the natural flow of water down rivers and through mountain gaps. Canals built in the 1800's redirected trade to locations consciously chosen by canal builders, often in a competitive fight with other canal builders. New York dug the Erie Canal, successfully redirecting trade away from both the Mississippi and St. Lawrence rivers to a port at the mouth of the Hudson River.

In Virginia, merchants in Alexandria and Richmond competed through investments in the C&O Canal up the Potomac River vs. the James River and Kanawha Canal up the James River. Politics reflected watershed boundaries, because commerce would literally flow along the canal path. In the dreams of Virginian canal builders, artificial rivers could be build so the agricultural products grown west of the Appalachian Mountains would be shipped from Alexandria or Richmond, and imports purchased by western farmers woulds flow through those Virginia ports.

Since the advent of railroads in particular, transportation networks can overcome physical barriers and steer economic growth away from one city and towards another. Fredericksburg and Norfolk in particular have seen periods of low growth as rival cities intercepted the trade that might have "naturally" flowed to those locations.

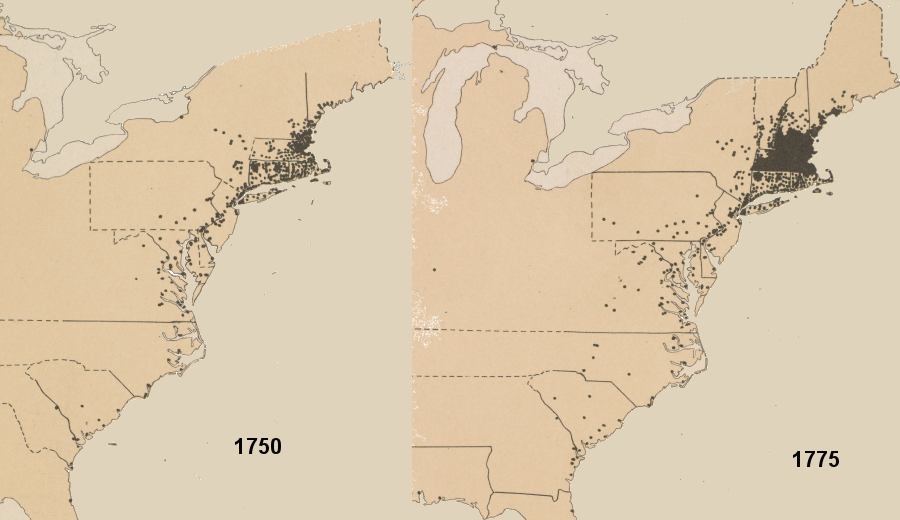

in 1750 colonial towns were common in New England but rare in Virginia - and the pattern was even more obvious in 1775 Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Colonial Towns, 1750 (Plate 61c) and Colonial Towns, 1775 (Plate 61d) digitized by University of Richmond |