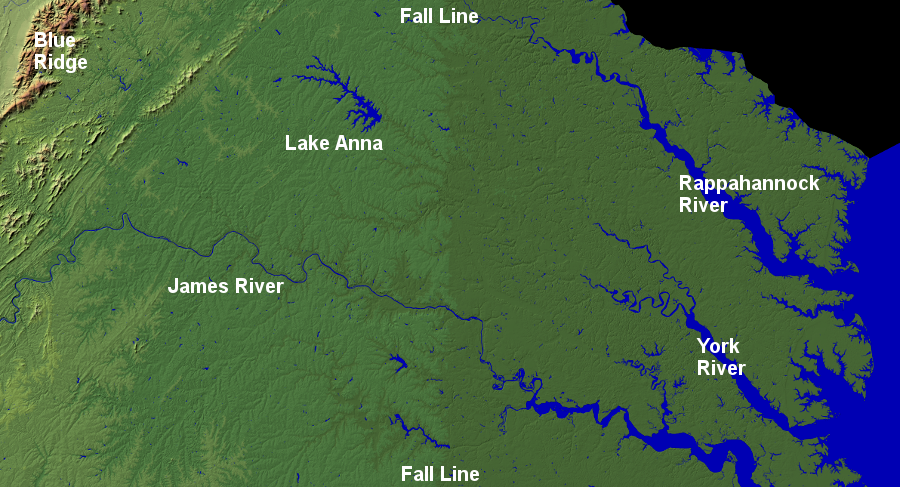

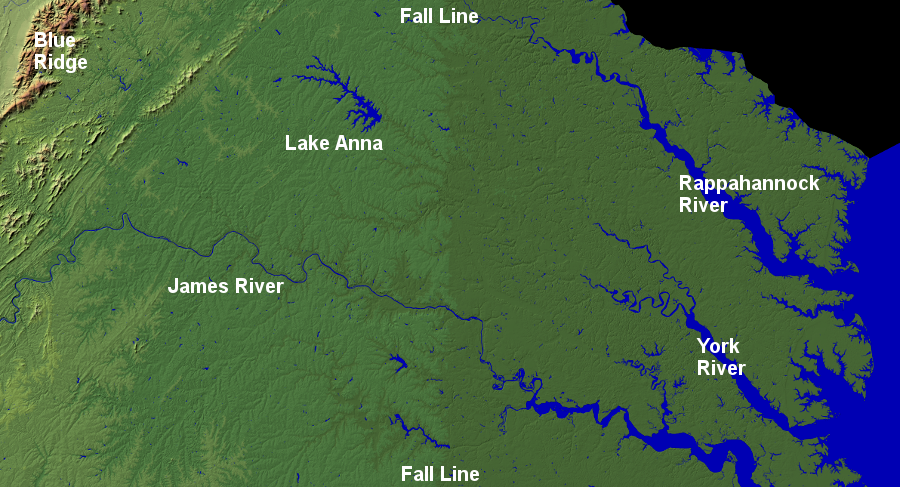

Virginia's Fall Line marks the boundary between the Coastal Plain and Piedmont physiographic provinces

Source: USGS Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, National Elevation Dataset - Shaded Relief Map of Virginia

Virginia's Fall Line marks the boundary between the Coastal Plain and Piedmont physiographic provinces

Source: USGS Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, National Elevation Dataset - Shaded Relief Map of Virginia

When English colonists arrived at Jamestown in 1607, they discovered that the Fall Line on the border of the Piedmont and Coastal Plain physiographic provinces separated the Siouan-speaking Monacan from the Algonquian-speaking paramount confederacy ruled by Powhatan. Monacan traders traveling downstream by canoe on the Rappahannock and James rivers had to portage around the rapids to go further east, or beach their canoes on the shoreline and walk to meet others with goods to exchange.

Ocean-going ships moved up the rivers, but rapids blocked them from sailing or rowing further upstream to get above sea level. Importing products from Europe, the Caribbean, and South America required all ships to stop at the Fall Line and unload everything into wagons (and later trains) for moving further west.

For the first century of colonization, English immigrants stayed east of the Fall Line where transportation by ship was readily available throughout the Coastal Plain. Colonists build just short roads from their farms to wharves on the James, Rappahannock and Potomac rivers. Fording creeks was a challenge, and dirt roads became muddy bogs during wet weather.

As colonial settlement moved inland, small boats from the interior could go downstream to the Fall Line carrying crops and timber products from farms and bars of pig iron from furnaces, but the colonists had to unload boats just like the Monacan. Further inland, rivers such as the Appomattox, North and South Anna, Rapidan, and Occoquan were too shallow for carrying large commercial loads across the Piedmont. Settlers gradually built roads suitable for a loaded wagon to reach the Fall Line in the mid-1700's.

the Fall Line in the York River watershed was too far upstream to justify development of a major city

Source: York River & Small Coastal Basins Roundtable

Warehouses were needed where goods were loaded and unloaded at the Fall Line, starting with storage for hogsheads of tobacco. Cities such as Petersburg, Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Alexandria developed where the geologic barrier blocked shipping. In 1732, William Byrd II had lots surveyed and "platted" the vacant land in anticipation of the development of Richmond and Petersburg. He knew that the Fall Line locations on the James and Appomattox Rivers were destined to grow into transfer points. In addition, the water power provided by the rivers allowed manufacturing to develop at those locations.

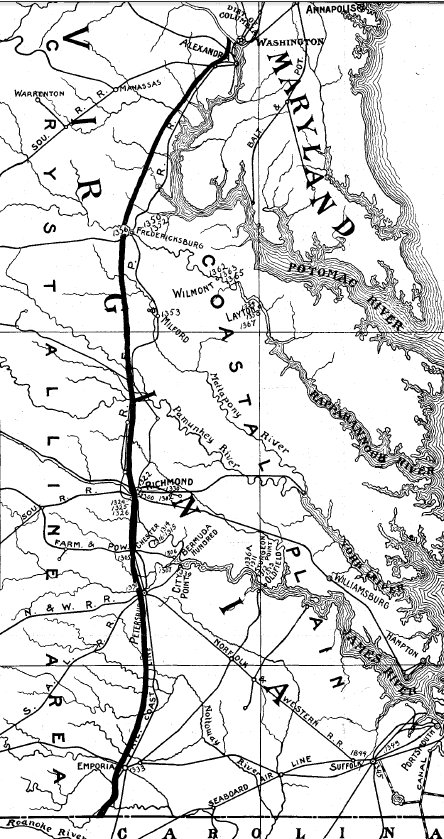

Alexandria, Fredericksburg, Richmond, Petersburg, and Roanoke Rapids developed at the Fall Line of the Potomac, Rappahannock, James, Appomattox, and Roanoke rivers

Source: Library of Congress, A general map of the middle British colonies, in America (Lewis Evans, 1755)

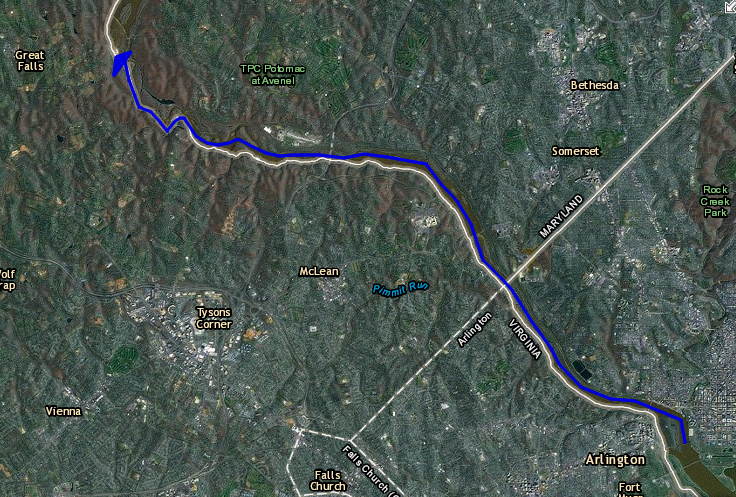

On the Potomac, the geologic barrier is Little Falls in the Potomac River and Georgetown developed there. Alexandria had less of a natural advantage for growth since it was not directly at the falls, but managed to grow because it offered a deepwater harbor and less delay for ships moving up the Potomac River.

Alexandria managed to become the market center for the Piedmont and Shenandoah Valley by expanding its road and railroad transportation network inland and west of the Blue Ridge. The initiative and speed of Alexandria merchants to connect to agricultural regions in the Rappahannock and Shenandoah watersheds drew agricultural trade from the backcountry to the Fall Line on the Potomac River, rather than to Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock River.

Great Falls has migrated upstream as the Potomac River etched into the metamorphic bedrock, but Little Falls blocked colonial shipping and determined where Georgetown/Alexandria would develop

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Occoquan got its initial start when the Lee and Carter families disputed access to the Potomac River at Great Falls. The Carters thought they could develop a copper mine on their land at today's Frying Pan Park in Fairfax County. The Lees quickly patented the lands along the Potomac River, forcing the Carters to build a "ox road" to the Occoquan for shipping the copper downstream. The copper deposits were insufficient to justify further development, however, and shipping via the Occoquan was always limited in scope.

All streams crossing the Fall Line did not end up with large cities. The Matta, Po, Ni, North Anna, and South Anna rivers cross the Fall Line, but on winding and shallow rivers. No large cities evolved on them in contrast to the Potomac, Rappahannock, James, and Appomattox rivers because:

There were fewer barrels of flour, fewer hogsheads of tobacco to be shipped downstream for commercial sale, and less of an upstream market for iron tools, clothing, glass, or other items not manufactured in the local area. Some small communities developed on the small rivers that cross the Fall Line such as Ashland, but they were limited in size because the topography limited the size of their natural "backcountry" or "hinterland" market.

That natural boundary could have been overcome by financing turnpikes and canals and railroads, as Baltimore accomplished with its investment in the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Small Virginia towns had limited access to capital, and were unable to match the investments made by the larger Fall Line cities such as Alexandria or Chesapeake Bay ports such as Norfolk and Baltimore. Fredericksburg was slow to expand its road and rail network into the "hinterland" towards the Blue Ridge, and the delay allowed Alexandria to capture trade from the Rappahannock River watershed.

Rappahannock River Fall Line - from I-95, headed north

The Appomattox River west of Petersburg is shallow, and does not extend to the Blue Ridge. Petersburg overcame that constraint; though not blessed with a large natural trading territory, the city still managed to become one of the most significant transportation centers in Virginia. The Union Army siege in 1864-65 was of Petersburg rather than the Confederate capital at Richmond, in part because Petersburg had developed a railroad network that stretched to South Carolina and Tennessee. The capture of Petersburg in April, 1865 blocked supplies from reaching Richmond and forced Confederate troops to evacuate the capital.

from Alexandria to Petersburg, cities developed on the Fall Line where ocean-going ships were forced to unload cargoes

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy (DMME), The Clay Deposits of the Virginia Coastal plain (1906)

Emporia on the Meherrin River is the one small Fall Line city in Virginia south of Petersburg. In addition to being located in a small watershed, the Meherrin lacks easy access to the Atlantic Ocean. It drains into the Albemarle-Pamlico Sound in North Carolina, where ships struggle to traverse the shallow, dangerous inlets between the barrier islands to reach the ocean. In contrast, shipping from cities in the Chesapeake Bay watershed could easily sail or steam between Cape Henry and Cape Charles with far fewer concerns regarding channel depth or currents threatening to drive them ashore.

The existence of a physical barrier does not by itself cause cities to develop. The next transportation barrier to the west of the Fall Line, encountered by Virginia settlers in the mid-1700's, was the Blue Ridge. There are no cities at the gaps through the Blue Ridge, because there was no requirement for shippers to shift at those gaps from one form of transportation to another.

The existence of a river does not by itself cause cities to develop. There are no urban centers on the Nottoway, the Powell, or the Clinch. Every Metropolitan Statistical Area (as defined by the Bureau of Census is centered on a river, but the development of Roanoke, Winchester, Harrisonburg, Roanoke, and Blacksburg had little to do with water transportation or even waterpower.

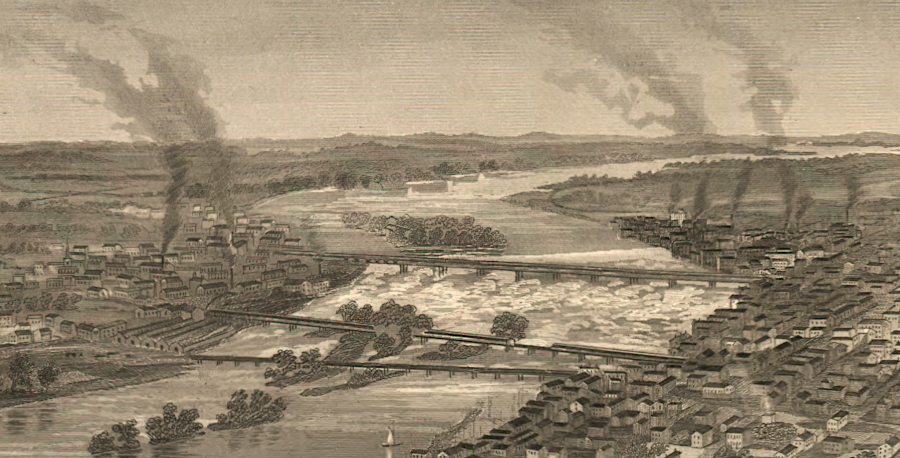

The Fall Line cities developed initially due to the transportation barrier. They grew into manufacturing as well as transportation centers because the topographic change at the Fall Line created waterpower, providing mechanical energy for powering equipment. Today we rely upon chemical energy from coal, gas, oil, or nuclear power and renewable energy from solar and wind to create steam and electricity. Until the 1900's, however, almost all manufacturing in Virginia was located at places where the facilities could rely upon waterpower.

Flour mills at Richmond and Fredericksburg, tobacco stemmeries at Petersburg, and iron furnaces at Falling Creek and Neabsco and then throughout the Valley and Ridge province relied upon the power of water to turn equipment such as stone grinding wheels or the bellows at the iron furnaces. Danville and Fries were able to develop as centers for textile processing because of the waterpower from the Dan and New Rivers.

the ability of falling water to power equipment, in the days before electricity, made Richmond a good location for manufacturing plants

Source: Library of Congress, Richmond, Va. and its vicinity (1863)

Lynchburg is not a Fall Line city. It is located where the trail parallel to the eastern flank of the Blue Ridge (now US 29) crossed the James River. Connections to Fall Line cities via the James River and Kanawha Canal, plus the South Side Railroad, spurred growth at Lynchburg. The James River crossing was close to the tobacco production area in Southside, and Lynchburg developed into a substantial tobacco processing town prior to the Civil War.

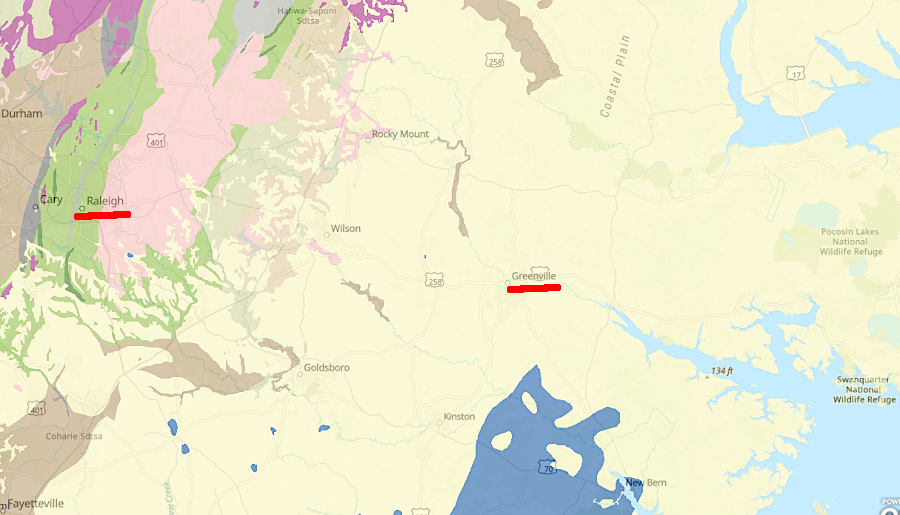

Further south in North Carolina, rivers cross a much wider Coastal Plain. Ships were blocked by narrow channels and shallow sections within the Coastal Plain, before reaching the crystalline bedrock of the Piedmont. Shipping up the Tar River, for example, stopped at Greenville, long before the Fall Line. Raleigh is often described as a Fall Line City, but is located on the Piedmont and was never a port equivalent to Richmond.

Raleigh is not on the geologic Fall Line, and narrow/shallow rivers forced colonial shipping in North Carolina to stop at Coastal Plain cities such as Greenville

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Geology of the conterminous United States