South Island hosted Virginia's largest colonial seabird nesting colony until 2020

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Border Collies Keep Birds at Bay at HRBT

South Island hosted Virginia's largest colonial seabird nesting colony until 2020

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Border Collies Keep Birds at Bay at HRBT

The two-lane Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel opened in 1957, and a two-lane set of parallel spans with a new tunnel was completed in 1976. Marine trestles carried traffic to human-constructed North Island and a South Island, with the tunnels buried underneath the shipping channel between the islands.

In 1983, South Island became a nesting colony for common terns and black skimmers. By 1985, the Virginia Department of Transportation had partnered with a faculty member at the College of William and Mary to manage the breeding seabirds and protecting habitat on the western half of South Island.

In 1993, gull-billed terns began nesting on South Island. They were joined in 1999 by laughing gulls. A year later, herring gulls and great black-backed gulls began nesting there. In 2006, royal tern breeding pairs started breeding on South Island, and sandwich terns arrived in 2010.

It was clear in 2017 that expanding the Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel would require paving the site of the nesting bird colonies and using that space for the construction project. In 2018 and 2019, the Virginia Tech Shorebird Program began studying how the birds were likely to react to displacement.1

two new tunnels were drilled through the seabed to connect North and South islands

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Expansion Project, Tunnel Boring

After the 2019 breeding season, the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) destroyed the nesting site of the largest multi-species waterbird colony in Virginia. The following year, the approximately 25,000 laughing gulls, herring gulls, black skimmers, gull-billed terns, royal terns, common terns, and other species migrating back from Central and South America would have to find a new space - or just fail to nest.

The birds had taken advantage of South Island when it was constructed 40 years earlier for the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel. They moved from nesting sites on Fisherman's Island and other barrier islands because the new artificial island was more isolated from predators, and was located in the middle of the open water habitat which provided food. The common terns foraged as far north as the mouth of the Rappahannock River before returning each night to the colony.

before being paved over in late 2019, the south island of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel was home to 25,000 nesting seabirds in the summer

Source: Google Earth (November 2015, April 2019)

The birds had not adopted the North Island because it had too much grass, which could hide predators. The Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel islands were paved, while the seabirds needed sand for their nest sites. The Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel islands were too small. The island next to South Island, where Fort Wool was built before the Civil War, had too many rats.

the parade ground of abandoned Fort Wool was covered with sand to create nesting habitat in 2020

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Conversion of Rip Raps Island

Until 2017, the US Fish and Wildlife Service had interpreted the Migratory Bird Treaty Act as requiring protection of the nesting area. Under President Trump, the Federal agency dropped any requirement for mitigation for "Incidental bird takes." The Virginia Department of Transportation could pave the six acres and use it for construction of the new tubes of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, and could end its multi-year search for alternative nesting sites.

Within the state, however, there was a strong reaction from bird lovers and people with a general sensitivity to environmental changes. Virginia had classified the gull-billed tern as a threatened species, and 98% of the royal terns nesting in Virginia used the six acres on the south island.

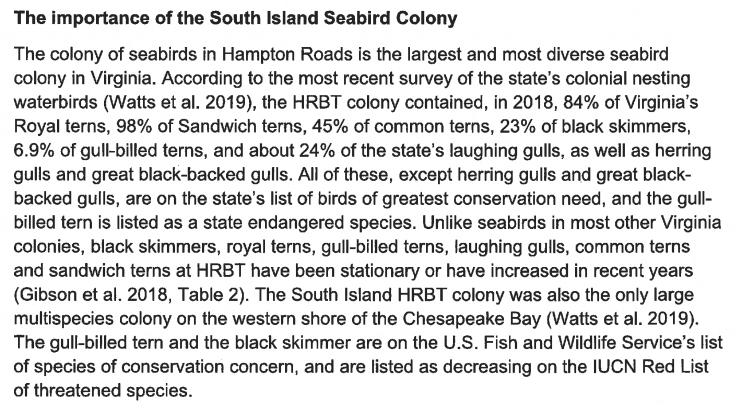

the significance of the nesting site at South Island was well known

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, permit application by Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (December 21, 2020)

State officials examined various locations before determining how to mitigate the impacts of eliminating South Island as a nesting site. Craney Island, Clump Island, Grandview Beach, and Fisherman Island had too little habitat and/or too many predators.

Plans to improve habitat on Willoughby Spit to encourage nesting there were dropped after the US Navy expressed concerns about increasing the hazard of bird strikes for planes using nearby Chambers Field at Naval Station Norfolk. The Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (DGIF) proposed building a new island as a new nesting site using dredge spoils. That could not be completed before the birds migrated back for the 2020 nesting season, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) expressed concerns about impacts on fish populations from dredging more deep water habitat outside of shipping channels.

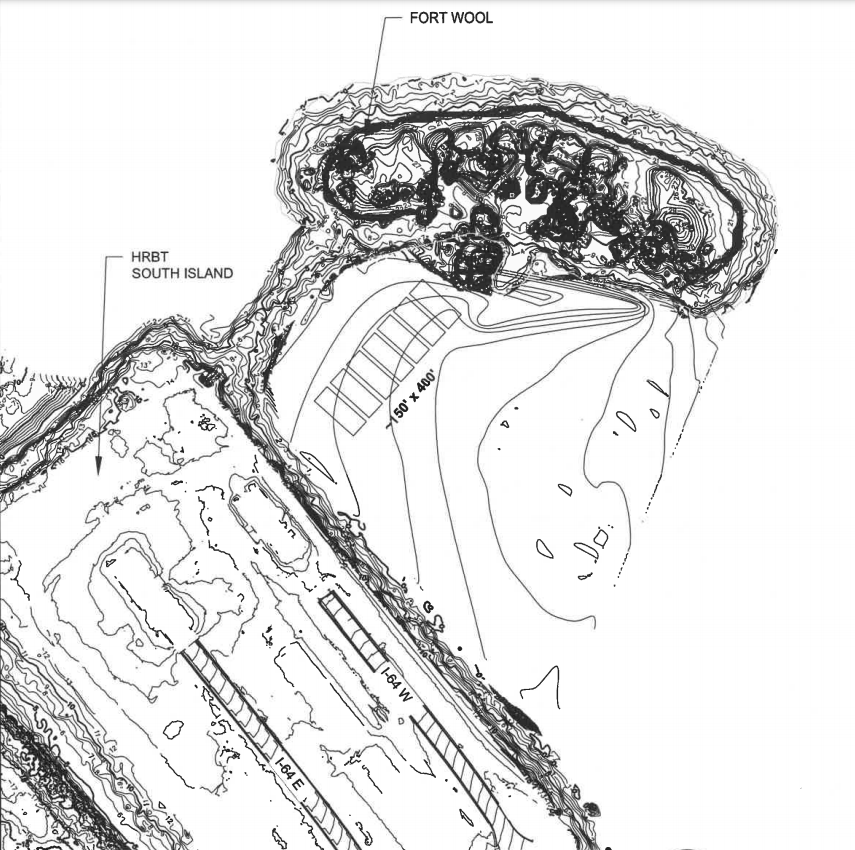

The solution to the loss of 10 acres at South Island was to upgrade 1.5 acres of habitat on Rip Raps Island in the parade ground of long-abandoned Fort Wool, and to trap rats there to protect nesting chicks.

Fort Wool before conversion into bird habitat

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Draft Detailed Project Report and Environmental Assessment (Figure 1-4)

Fort Wool had vegetation before being converted into a replacement "bird magnet" in 2020

Source: GoogleMaps

The state also provided an extra acre of habitat by placing seven barges next to Rip Raps Island, with a layer on sand on the barge deck to provide nesting sites. Construction on the south island in 2018 had forced the royal terns to nest closer than normal to the herring gulls, and the gulls had feasted on the tern chicks. Barriers were designed to keep the chicks from running off the barges and drowning.

in 2020, royal terns quickly began nesting in the new sand placed at Fort Wool

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Fort Wool and Barge Artificial Habitats (May 20, 2020)

barges expanded the acreage of bird habitat at Fort Wool

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Draft Detailed Project Report and Environmental Assessment (Figure 2-3)

To facilitate recovery of the gull-billed tern population, state officials also revised laws to allow for relocating nests and eggs of a state-threatened species. That allowed Department of Game and Inland Fisheries staff to move birds who tried to nest on the now-paved south island over to Rip Raps Island.

Dogs that normally prevented non-migratory geese from nesting were hired to patrol the south island and force birds to move to other places for nesting. The Virginian-Pilot reported:2

border collies, wearing protective goggles and foot coverings, chased birds off South Island in 2020

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Border Collies Keep Birds at Bay at HRBT

The effort, which cost the Virginia Department of Transportation over $2 million and was accomplished in just three months, was successful. Removing the vegetation had created a 360-degree view, allowing the nesting birds to detect threats. Rats were exterminated. Buildings were sealed to prevent birds getting trapped, or damaging historic structures with their droppings.

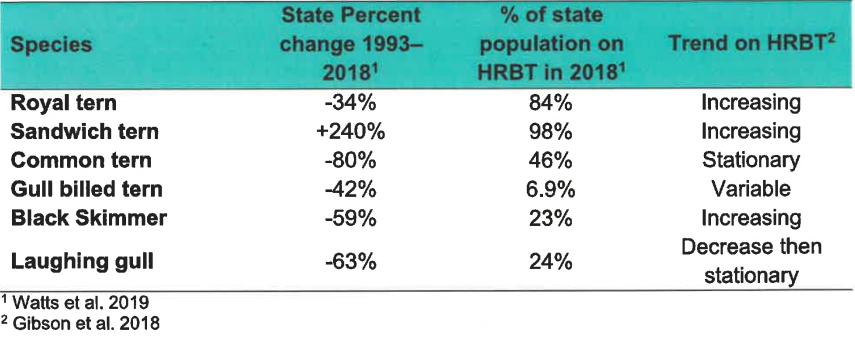

Fort Wool and seven barges in 2020 enabled successful nesting by Royal Terns, Sandwich Terns, Laughing Gulls, Common Terns, Black Skimmers, and Gull-billed Terns to nest successfully

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, permit application by Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (December 21, 2020)

In addition to making Fort Wool and the barges more attractive, the harassment at South Island by noisemakers, decoys, and dogs deterred nesting there. One Virginia Department of Transportation official noted:3

barges provided another acre of habitat

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Creation of an Artificial Floating Island

after barges were installed and covered with sand, decoys were added to attract birds

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Fort Wool and Barge Artificial Habitats (May 20, 2020)

Moving the colony just a short distance improved the safety at South Island, since it was no longer a "bird magnet." There were fewer collisions between vehicles emerging from the tunnels and adult birds. Chicks no longer hopped into traffic, which occasionally caused drivers to make an emergency stop that triggered rear-end collisions.

The move also made South Island a more attractive location for the workers. Some birds had the habit of dropping oysters to break the shells and expose the meat. It was not unusual for employees working at South Island to discover, when their shift was over, cracked windshields on their cars. Seafood-eating birds produced smelly feces, and:4

Laughing gulls had created the greatest problem. That aggressive species started nesting in 2000, and dive-bombed workers regularly. A biologist hired to coat their eggs with oil to deter laughing gull nesting commented:5

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR), DWR Creates New Home for Seabird Colony on Fort Wool

At the end of 2020, the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources filed for a permit from the Virginia Marine Resources Commission to anchor 2-10 barges next to Fort Wool, for an expected five-year period. The state agency estimated it would cost $10 million to provide up to 1.5 acres of temporary bird nesting habitat between mid-March and mid-September for five years. The 2020-2021 cost was $2.2 million.

the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources sought approval to anchor up to 10 barges to provide temporary bird habitat between 2021-2026

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, permit application by Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (December 21, 2020)

"Lessons learned" from 2020 included installing the barges earlier to catch the beginning of the nesting season, spreading the aggregate/sand on the barges before towing them into place, and installing wave shields to prevent nesting material from washing overboard during storms and high wind events. The Department of Wildlife Resources decided to use four larger barges in 2021, providing 50,000 square feet of nesting area compared to the 40,000 square feet on seven barges in 2020.6

side walls were added to barges to keep chicks from falling overboard

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Tired of Netflix? Enter the World of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Seabird Breeding Colony

After Fort Wool was converted to bird habitat in 2020, tourist visits from Hampton ended. The Miss Hampton II had carried passengers for over 30 years to the island. In 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the owners of the 117-passenger vessel sold it to a company that moved the boat to Cape Henlopen. The last harbor tour by the Miss Hampton II was on July 28, 2021.7

tours to Fort Wool by the Miss Hampton II ended when the site was converted to bird habitat

The nesting bird population grew after being transferred to Fort Wool and the barges, but managing the one acre of habitat cost $3 million per year. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources planned to build a new 10-acre island within 13 miles of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, at a cost of $10 million. The larger site was expected to accommodate the 25,000 birds of multiple species.

relocation of the nesting colonies was successful, and Fort Wool was crowded with birds starting in the 2020 nesting season

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Conversion of Rip Raps Island

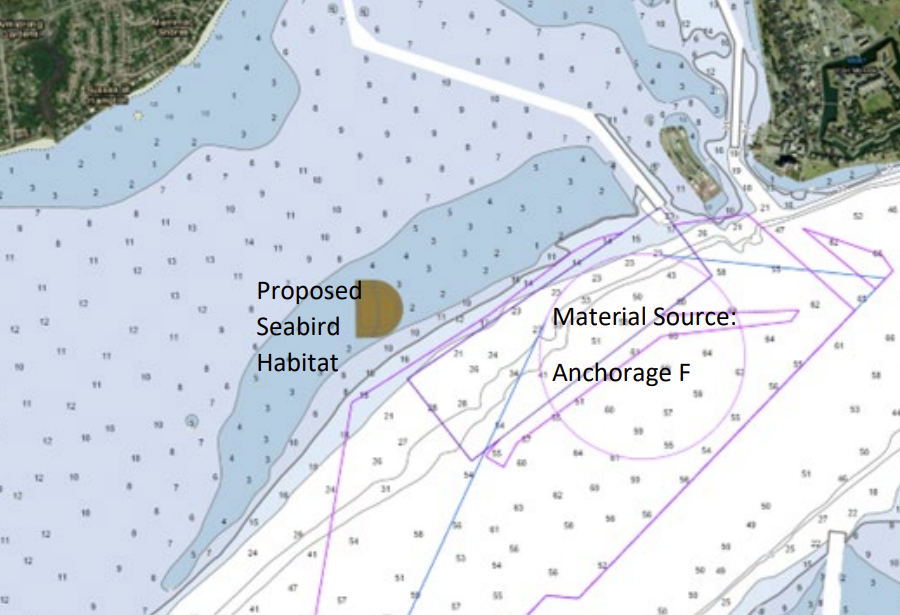

To start, 28 locations were identified that were outside of shipping lanes and isolated from predators, where dredged material could be used to create an island. The state agency was confident that the bird colonies could be moved a second time. The plan was to complete the new island before the 2026 nesting season started.8

seabird colony at Fort Wool

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Draft Detailed Project Report and Environmental Assessment (Figure 1-3)

In 2024, The Hampton City Council passed a resolution asking the state to take action and restore public access to Fort Wool. State agencies were still planning to create an artificial island, but the source of the sediments was tied to a project to create a new mooring spot for ships that needed to "park" before they could move to an available berth at a shipping terminal. The city assumed Fort Wool would be restored to its historic condition, including removal of the sand cover placed there for the birds, before a new lease would be offered by the state for the city to offer tourist visits.9

The cost of renting the barges, $2.6 million per year, was financially unsustainable. In addition, the US Coast Guard required the barges be moved to a more secure location in case a named storm event struck Hampton Roads, even during the nesting season, to ensure the barges would not crash into the Hampton-Roads Bridge-Tunnel or otherwise interrupt shipping traffic.

Reproduction of r black skimmers, common terns, and gullbilled terns in particular dropped after being forced off South Island. The permanent solution for the seabird colony was a US Army Corps of Engineers proposal to spend $16 million to construct a 10-acre island in Hampton Roads, followed by restoration of Fort Wool.

Dredge spoils from the deepening of Anchorage F and the channel into Norfolk would be used to build a new horseshoe-shaped island one mile south of Hampton. The habitat would occupy half of that new island. The state's 35% share of the cost, $5 million, was equivalent of two years of cost for renting the temporary barges.

a new island for the seabird colony was planned near the City of Hampton

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Draft Detailed Project Report and Environmental Assessment (Figure 5-2, Figure 5-1)

Converting Fort Wool back into a historic site was projected to cost $7 million. Half of that cost was for a new pier, so tour boats could dock again at the island. An estimated $611,000 would remove the acidic bird guano which was etching into the concrete and steel structures. The site was owned by the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, so the City of Hampton sought state funding for the restoration of Fort Wool.10

as hoped, nesting seabirds moved from South Island to Fort Wool in 2020

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Seabird Conservation in Hampton Roads

barges between the South Island and Fort Wool provided nesting habitat in 2020

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, HRBT Expansion Magazine (Winter 2020)

Maryland has also created artificial platforms to expand nesting habitat, as natural islands disappear

Source: Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Nesting Platform Initiative in Maryland Coastal Bays Begins Second Year and Nesting Platform Initiative Launched for Endangered Birds in Coastal Bays