a pre-World War II postcard shows the James River Bridge, linking Isle of Wight County to what is now the City of Newport News

Source: Boston Public Library, Newport News -- James River Bridge

a pre-World War II postcard shows the James River Bridge, linking Isle of Wight County to what is now the City of Newport News

Source: Boston Public Library, Newport News -- James River Bridge

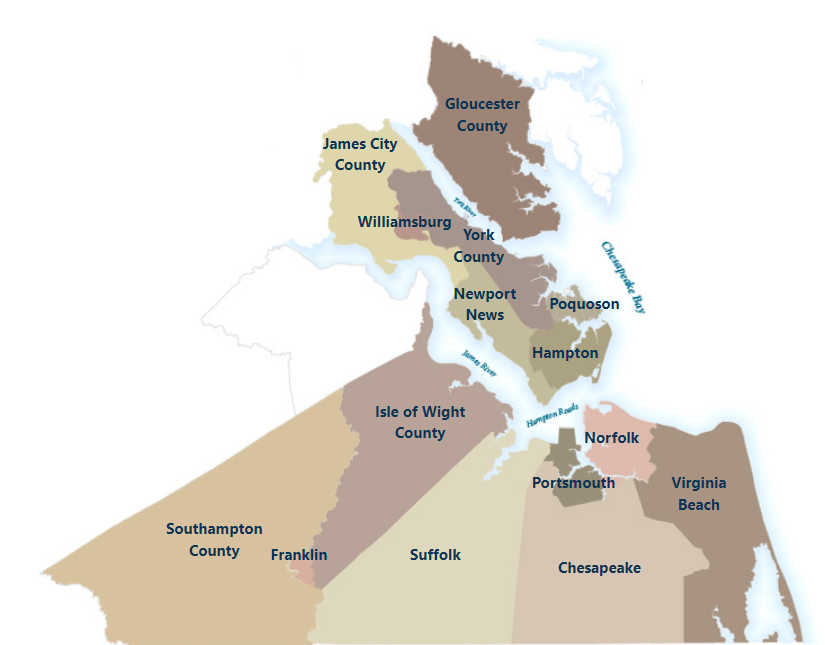

In Hampton Roads, decision-making is balkanized. Leaders in different cities and counties have difficulty setting priorities other than "my jurisdictions first." Even the coordination organizations are hard to coordinate.

The Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization (HRTPO) was created in the 1970's, after the Federal government mandated that all urbanized areas with a population greater than 50,000 people coordinate transportation planning. Metropolitan Planning Organizations must create long-range (20-year) metropolitan transportation plans.1

The Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission (HRTAC), Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization (HRTPO), and Hampton Roads Planning District Commission (HRPDC), coordinate priorities for the region. Membership varies between those organizations.

Some local jurisdictions belongs to the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization and coordinate transportation planning, meeting a Federal requirement to obtain funding. Different local jurisdictions belong to the Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission and coordinate transportation planning, to allocate the special revenues in the Hampton Roads Transportation Fund.

Gloucester County, for example, is part of the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization (HRTPO) but was not included in the Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission (HRTAC). Since Gloucester County is not one of the jurisdictions authorized by the General Assembly in 2013 to increase taxes for transportation projects, it does not vote on how to use Hampton Roads Transportation Fund revenues.2

In contrast, in 2013 the General Assembly included Southampton County and the City of Franklin as members of the Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission (HRTAC), even though they are not members of the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization (HRTPO). Those two jurisdictions do have access to the extra revenues in the Hampton Roads Transportation Fund.3

Surry and Southampton counties, plus the City of Franklin, belong to the Hampton Roads Planning District Commission (HRPDC)

Source: Hampton Roads Planning District Commission

Surry and Southampton counties, plus the City of Franklin, belonged to the Hampton Roads Planning District Commission (HRPDC) in 2014 but were not part of the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization (HRTPO)

Source: Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization, At-a-glance

Gloucester County is not part of the Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission (HRTAC) and gets no revenue from the Hampton Roads Transportation Fund created in 2013 - unlike Southampton County and the City of Franklin

Source: Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission (HRTAC)

Surry County belongs to belong to the Hampton Roads Planning District Commission and participates in regional initiatives, but is not part of either the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization or the Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission.4

Surry County's involvement in transportation planning is limited, and it has few road projects or needs that would affect nearby jurisdictions. Only a tiny portion of Surry County is crossed by US 460, one of the roads expected to be improved with revenues from the 2013 tax increases.

very little of US 460 crosses Surry County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Hampton Roads Economic Development Alliance jurisdictions (2014)

Source: Hampton Roads Economic Development Alliance

the City of Williamsburg is not included in the Peninsula Chamber of Commerce jurisdictions (2014)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the Hampton Roads Chamber of Commerce jurisdictions includes Mathews County - and Currituck County in North Carolina (2014)

Source: Hampton Roads Chamber of Commerce

For decades, the political conflict between "North" Hampton Roads and "South Hampton Roads" blocked efforts to get additional transportation funding from the General Assembly. In the eyes of Hampton Roads officials on both sides of the water, Northern Virginia and other regions were able to direct transportation funding to their projects, but southeastern Virginia projects were rejected due to the lack of regional consensus on priorities.

In 2013, the state legislature authorized a 0.7% sales tax increase plus a 2.1% increase in the fuel tax in Hampton Roads. The new taxes were part of a major increase in transportation funding statewide, passed in a law known as "HB 2313." HB 2313 was expected to raise $8-10 billion in additional revenue over the next 20 years for the new Hampton Roads Transportation Fund.

In 2013, the governor and legislature found the political compromise needed to raise taxes for new transportation projects, and did so consistent with the Constitution of Virginia. The legislature approved new taxes for the Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads regions in HB 2313, but Richmond and nearby jurisdictions in the Central Virginia region were unable to cooperate and get that authority for new taxes.

The state legislature gave the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority, a regional organization created in 2002, authority to allocate funds to regional projects in that area. An equivalent Hampton Roads Transportation Authority had been created in 2007, but it had been abolished after the Virginia Supreme Court blocked the 2002 effort to raise regional taxes for transportation.

After passing HB 2313, the General Assembly could have given the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization control over the new revenue. That organization's track record for resolving regional conflicts and making decisions on transportation priorities was poor, so in 2014 the General Assembly created a new political mechanism. The 23-member Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission was given control over the new Hampton Roads Transportation Fund.

The Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission did not gain control over all transportation funding; the cities retained their traditional funding for maintainence of roads and bridges. The new HB 2313 taxes did re-set the political debates, however. By deciding which projects would be funded from the new transportation tax, the Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission gained the power to steer decisions on new construction.

The agency can also set tolls on different projects, providing a way to balance the impacts so each jurisdiction suffered a fair share. To ensure funding priorities are not too biased towards one part of Hampton Roads, the commission requires 2/3 of elected officials, representing 2/3 of the region's population, to approve projects.

The governor made clear even before the first official meeting of the Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission that regional officials were now accountable for solving the regional transportation challenges. With the new taxes and a new group for making decisions, Hampton Roads leaders were challenged to go beyond standard political rhetoric and to resolve long-recognized problems:5

At the commission's first meeting, however, it took nine votes before the members could elect the chair (the mayor of the City of Chesapeake) and five votes to choose the vice-chair (a state senator). A reporter noted that the commission was structured so the jurisdictions with the largest populations have more voting authority, but:6

Virginia Port Authority terminals in Hampton Roads

Source: Virginia Port Authority

Portsmouth in particular has felt aggrieved by the decisions of state officials. Under the state the Public Private Transportation Act (PPTA), the Virginia Department of Transportation contracted with a private company, Elizabeth River Crossings, to build a second Midtown Tunnel (as well as improving the Downtown Tunnel and extending the Martin Luther King Freeway).

Tolls were re-established on Downtown and Midtown tunnels in 2014, helping to finance the second tube for the Midtown Tunnel. All of South Hampton Roads will benefit from the expanded transportation capacity - but because jobs are concentrated east of the Elizabeth River, Portsmouth residents commuting to work will pay 6-8 times more in tolls than residents in Virginia Beach and Norfolk.7

An analysis that compared the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority to the Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission identified parochialism as the biggest challenge in southeastern Virginia:8

A lobbyist for new highway projects in Northern Virginia suggested that the cooperation in the DC suburbs was due to a unified business community that pressured elected officials to work together on long-term objectives, rather than fight for local improvements that could be cited during re-election campaigns:9

The new Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission chose to create a separate staff, independent from the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization and the Hampton Roads Planning District Commission. The alternative was to hire one executive director and have that person be accountable to three separate boards, an approach considered unrealistic by the state delegate who sponsored creation of the Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission.

As a result, three separate agencies (Hampton Roads Transportation Accountability Commission, Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization, and Hampton Roads Planning District Commission) coordinate transportation projects and priorities for the region.10

The most expensive transportation project proposed for the region is a "Third Harbor Crossing" of the Hampton Roads harbor, to connect the Peninsula to South Hampton Roads. Officials on the Peninsula advocated for an expansion of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (I-64) linking Norfolk and Hampton. Support on the southern side of Hampton Roads was stronger for the third crossing, renamed the "Patriot's Crossing" option.

The Patriot's Crossing proposal includes an east-west bridge-tunnel connecting the Monitor-Merrimac Bridge-Tunnel to Norfolk, plus a north-south road in the middle of the new bridge-tunnel that would cross Craney Island to connect to I-64 in Portsmouth.

The 2013 legislation that authorized extra taxes for transportation projects focused on road construction, and did not address a fundamental flaw in transit services. Hampton Roads Transit was funded exclusively by annual payments from its member jurisdictions, and was unable to carry over surplus funding at the end of a budget year in order to fill funding gaps for the next year. Whenever revenues exceeded costs, the cities who were part of the regional transit system got repaid. Whenever costs exceeded revenues, the cities had to scramble to deliver unplanned money.

Hampton Roads Transit was created in 1999 by the merger of Tidewater Regional Transit (operating in Norfolk, Virginia Beach, Portsmouth, Chesapeake and Suffolk south of the James River) and Pentran (serving Newport News, Hampton on the Peninsula). The merger created a regional entity to manage transit services, the Transportation District Commission of Hampton Roads. Suffolk withdrew from it and began contracting for a separate bus service in 2012.

In 2020, the General Assembly addressed the problem. It authorized extra taxes for the Hampton Roads Transit system, and simplified its budgeting by allowing retention of surplus funds across fiscal years.11

Patriots Crossing, as proposed

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Patriot's Crossing

in 2022, 13 jurisdictions were voting members of the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization

Source: Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization

in 1755, there were few roads south of the James River

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1755)

the southern approach of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel crosses Willoughby Spit in Norfolk

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Expansion Project, DBE/SWaM Opportunity Event (September 11, 2019)

Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, looking from Newport News towards Norfolk befor expansion

Source: Hampton Roads Crossing Study EA Re-evaluation of the SEIS - Study Updates