Elfreth's Alley in Philadelphia, one of the oldest continuously-used residential streets in the United States, was a mixed use community with businesses on the first floors

Elfreth's Alley in Philadelphia, one of the oldest continuously-used residential streets in the United States, was a mixed use community with businesses on the first floors

Landowners in Virginia own private property, but do not have unlimited control over that land. After World War I, legal decisions made clear that zoning was part of the "police power" of local government. Local official in Virginia's counties, cities, and towns have some control over development of private property. Your home may be a castle - but adding an addition to the castle requires a local permit.

Key land use planning issues in Virginia today are:

1. how much control will the county/city/town exert over the development of private land

2. what type and density of development will be authorized on a particular parcel

3. who will pay for new public infrastructure (such as roads, schools, fire/police stations, libraries, parks) to support new development

Local officials - not the General Assembly, not the US Congress - make local land use decisions. "Smart growth" implementation requires action by local officials, but state/Federal officials play a key role by shaping the use of state/Federal funds for transportation and sewers.

County supervisors or city/town councils adopt long-term visions in "comprehensive" land use plans, plus more-detailed zoning ordinances that limit development potential and define acceptable use (residential, industrial, commercial, etc.) for each parcel of land. Local officials approve parcel-specific site plans to ensure compliance with erosion and sediment controls, design standards for fire protection, etc.

In Virginia, local governments are subsidiaries of the state government. The General Assembly provides authority to the counties and cities through charters, and under the Dillon Rule local governments can only exercise authorities that have been specifically granted. The local ordinances must be consistent with overall state law, but they are the law of the land, the rules to follow.

Because so much money is at stake, the developers may resort to the courts to interpret the rules and to clarify what authority has been granted to local governments. Virginia follows the Dillon Rule, a legal concept that strictly limits the power of local government. Under the Dillon Rule, counties may not impose more limits on developing private property than the General Assembly has authorized in the Code of Virginia. As stated by the State Supreme Court in an 1999 case to determine whether certain provisions in a county's subdivision ordinance violated the Dillon Rule:1

County/city/town officials clearly have the authority to limit the subdivision of private property into additional parcels that can be developed, and to ensure that zoning controls land uses. Local officials can approve, require modifications before approval, or even reject subdivision proposals and the site-specific detailed plans when a parcel is developed.

Local jurisdictions have numerous ordinances that affect land use. Erosion and Sediment (E&S) control ordinances may mandate grading plans, based on the square footage of land from which vegetation will be removed. Ordinances establish the basic mitigation measures that will be required by local officials for erosion and sediment control, and county officials interpret those plans to see if they are in compliance with the ordinances. When site plans are submitted by developers to local government officials for approval, the administrative interpretations can have a major impact on the development potential (and thus the $$$ value) of a parcel. The number of buildings and location of roads, including setbacks from adjacent parcels, can maximize profits if the constraints are minimized through staff interpretation - or kill a project, if the limits on development are interpreted tightly.

Comprehensive plans, zoning ordinances, subdivision ordinances, erosion and sediment control ordinances - all the local requirements vary by county/city/town. The different requirements have created a demand for local lawyers who understand the quirks in the requirements, and know how the staff in each jurisdiction will interpret the requirements. Regional or statewide consistency is rare in Virginia's land use planning process - even statewide requirements such as the Chesapeake Bay Regulations are interpreted differently by different jurisdictions. The extra legal fees make development more expensive, so homeowners and businesses end up financing the desire of local governments to stay independent.

In rural areas where little development is underway, the local controls may be minimal. Investment in a rural county would bring jobs and increase tax revenues to support local services, allowing elected officials to improve schools, hire more sheriff deputies, expand the library, etc. In those places, local officials are not inclined to create requirements to control growth, and expanding the county bureaucracy to review development proposals would require additional taxes on local voters.

In urbanizing areas such as the suburbs near Richmond, Hampton Roads, and Northern Virginia, control over how private property is developed may be a contentious process involving landowners and their lawyers, neighbors or local residents upset over additional development, and local officials. In Fairfax, Loudoun, and Prince William counties over the last 30 years, the Board of County Supervisor election campaigns have been based on growth management issues. Local officials have reacted to citizen complaints, and incumbents have been voted out of office because they were either too supportive of growth or too restrictive.

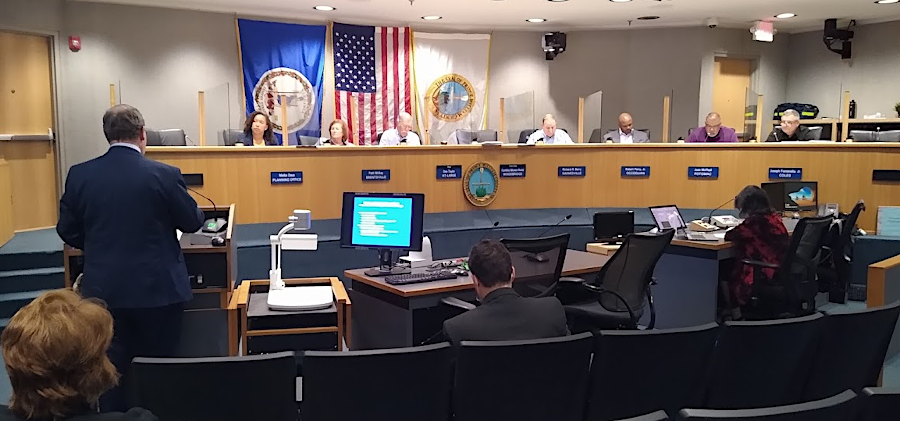

public work session, with Prince William County staff briefing the Planning Commission in 2021

In theory, planning department staff working for the Board of County Supervisors are caught in the middle between landowners/developers seeking to convert property to its "highest and best use" vs. local citizens who object to overly-intensive development. In practice, the developers "play the game" better because they are involved every day in the process, and have a strong economic incentive to win.

Profits are higher if the density of housing or commercial development permitted by local government is maximized, and mitigation measures to reduce impacts on the neighbors or community are minimized. Urbanizing counties tend to require mitigation measures such as "proffers" from the developers of free land for schools or libraries,

Neighbors are usually inexperienced in the process, and rarely get involved in the early stages when there is more flexibility to revise the planned development. Once a developer has prepared detailed site plans for subdividing a farm, laying out where the roads and houses will go and how dirt will be moved to accommodate the maximum density (or more) permitted under the local ordinances, it would be expensive for a developer to revise the proposal based on feedback in public hearings.

Land use planning is not just an analytical, academic exercise conducted by professional staff in a county office. Plans and ordinances can create windfalls for some landowners and wipeouts for others - or force the county supervisors to raise taxes on all residents in order to fund schools and other public services. Landowners may seek to have public roads improved near their parcels, in order to increase the value of their nearby private land. In counties where population growth is minimal and development potential is low, land use plans won't have much impact on land values. In high growth areas where land values are rising as demand for housing and office space is increasing, however, land use planning is almost always a highly-charged political issue.

"Smart growth" advocates are encouraging rapidly-growing areas to concentrate housing near jobs and existing public facilities, to minimize the cost of building new roads, libraries, schools, etc. Private property owners who recognize when land use proposals may reduce the development potential of their land usually respond with political action and even lawsuits, to ensure their land is not reduced in value by "downzoning."

Both landowners and county officials must comply with the ordinances. Each county has staff who process proposals for development and issue approvals, or deny authorization. It's a tough job to work the counter and deal with the workload, especially when a building boom hits an area. In addition, the staff often earn their pay when dealing with landowners who react unfavorably to denials.

Decisions of county officials can be appealed. Not only do developers need to know the rules of the game, but they also need to know the players. The Supervisors can overturn a decision of staff. In addition, there is a Board of Zoning Appeals - usually a low-visibility operation, but one that wields great power.

The state courts are the "referees" to determine if land use decisions violated some aspect of various state laws, or if the land use rules violated the state constitution in some way. (It is rare for land use cases to end up in Federal courts.) Those involved in land use planning in Virginia must understand the impacts of case law, interpretations of the rules based on court decisions on individual cases, as well as the state statutes and county ordinances.