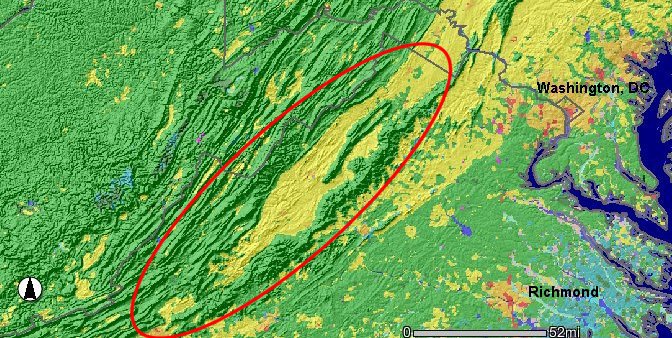

Valley of Virginia (Shenandoah and Roanoke River valleys)

Source: US Geological Survey, Seamless Data Viewer

Valley of Virginia (Shenandoah and Roanoke River valleys)

Source: US Geological Survey, Seamless Data Viewer

Native Americans lived in the Shenandoah Valley for about 15,000 years before the first Europeans arrived. By the 1600's, the region included grasslands and savanna. It was not a primeval forest, totally covering the land, because Native Americans used fire to manage the landscape. They created corridors of open pine and oak forest, with patches of open fields where bison and elk grazed.1

Source: Samuels Library, Native American Communities of the Shenandoah Valley (by Dr. Carole Nash)

John Lederer was the first European to document seeing the valley. In 1670 he reached the crest of the Blue Ridge, perhaps near where I-66 passes through today. He reported wandering in snow before choosing to return to the Piedmont on the east side of the mountain.

The first European explorer to document being within the valley was Frantz Ludwig Michel (Francis Louis Michel). He was searching for land to settle Swiss Anabaptists from the canton of Bern, and went from the Potomac River south to near modern-day Edinburg.2

Virginia's colonial governors sought to recruit Protestant immigrants who would live in the backcountry and provide protection against Native American raids. Virginia officials also feared the French would move eastward and establish claims to lands near the Allegheny Front, so they were willing to allow non-Anglican immigrants who did not even speak English to settle in the Shenandoah Valley.

That settlement was spurred by war in Europe. Armies marched through the Holy Roman Empire in the 1700's, driving German-speaking refugees to flee to North America. Scotch-Irish settlers in Ireland also chose to cross the Atlantic Ocean, as England discriminated against their products and made America a more attractive option for economic advancement.

The first settlers arrived from Pennsylvania, walking down the Great Valley to find lower-cost farmland further away from Philadelphia. Jost Hite, John Van Meter, and Isaac Van Meter obtained grants from Governor Gooch for land near the Potomac River in 1730-31. Later immigrants moved steadily south, some to avoid dealing with Lord Fairfax's claims to the northern half of the Shenandoah Valley.

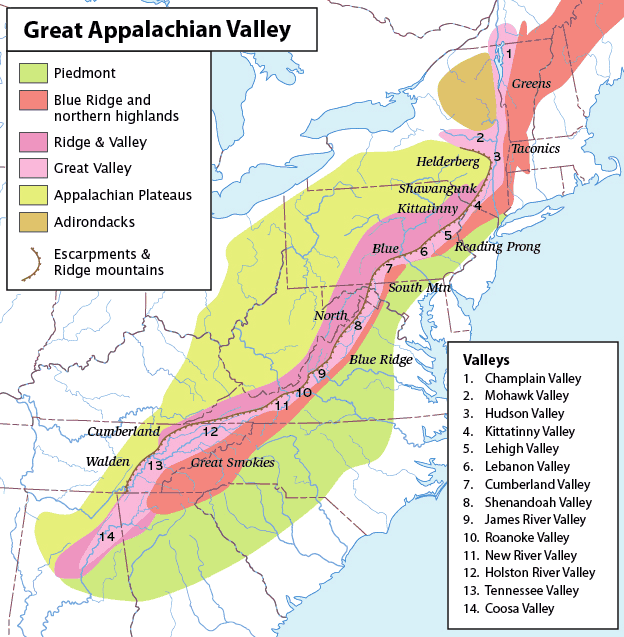

the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia (bounded by red line) is part of the Valley and Ridge physiographic province

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), US National Parks from Space

Geographer Robert Mitchell identified a three stage model for settlement of the Shenandoah Valley:3

The boundaries of the Shenandoah Valley region can be defined many ways, some extending outside the watershed on the Shenandoah River. One option is to include the land:

That definition would include land in the James River watershed. The watershed divide is not clearly obvious; the ridge appears to be just another low hill. Natural Bridge is a landmark feature of the Valley and Ridge physiographic province, but placing it in the Shenandoah Valley might be unacceptable to some observers. Similarly, Lexington is often paired with Staunton as two historic sites in the valley - but which valley? The Maury River, which runs through the northern edge of Lexington, is a tributary of the James River.

Using a more-restrictive definition, the Shenandoah Valley could be limited to just the drainage of the Shenandoah River. That would exclude Natural Bridge, Lexington, and Rockbridge County. The watershed divide between the Shenandoah and James rivers is close to the Augusta/Rockbridge county line. Just south of Staunton, the Steeles Tavern exit on Interstate 81 identifies a high point on the watershed divide between the Potomac and James river watersheds.

The Shenandoah Valley is a subunit of the Valley and Ridge physiographic province, and so is the Roanoke River valley west of the Blue Ridge. When travelers going south on I-81 from the James River reach the watershed divide separating the Roanoke and James rivers, they see a "Leaving the Chesapeake Bay watershed" sign posted on I-81. The Roanoke Valley is part of the generic "valley" west of the Blue Ridge, but few would consider it as part of the Shenandoah Valley.

One way to lump all the names is to refer to the "Great Valley." That term can include valleys north of the Shenandoah River, especially the Hagerstown/Frederick Valley in Maryland and the Cumberland Valley in Pennsylvania.

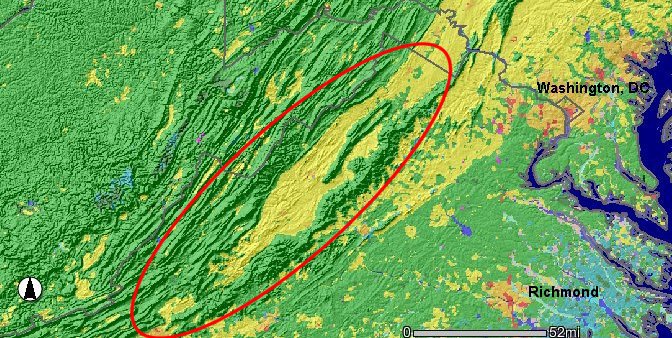

the Shenandoah Valley was formed by the same depositional and tectonic events as the Great Valley in Pennsylvania

Source: Pennsylvania Geological Survey, Physiographic provinces of Pennsylvania (compiled by W.D. Sevon, 2000)

There is no obvious physical difference in the landscape or barrier to travel on the southern end of the valley until you reach the James River, and there are no obvious cultural differences between residents of Augusta and Rockbridge counties. The limestone soils in the Great Valley enabled Augusta and Rockingham to become the dominant agricultural producers in Virginia.

Source: Virginia Museum of Natural History, Geology of the Shenandoah Valley

farms cover the landscape along the North Fork of the Shenandoah River, north of Timberville

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Earth Observatory, Rocky Mount Fire, Virginia

The famous McCormick reaper was developed on a farm near Steeles Tavern; wheat farming was common throughout the valley, south to Lexington and north to Winchester, in the 1850's. The region was the "Granary of the Confederacy" in the Civil War, until the Burning Raid by General Sheridan in 1864 destroyed many barns and limited the agricultural capacity of the valley.

Shenandoah Valley in 1941, with wheat stacks in background

Source: Library of Congress, Scenes of the northern Shenandoah Valley, including the Resettlement Administration's Shenandoah Homesteads

haystacks in the Shenandoah Valley, 1941

Source: Library of Congress, Scenes of the northern Shenandoah Valley, including the Resettlement Administration's Shenandoah Homesteads (by Ben Shahn, 1941)

The alignment of the Blue Ridge mountains and the valley shaped military strategy in the Civil War. As one prominent historian described the region:4

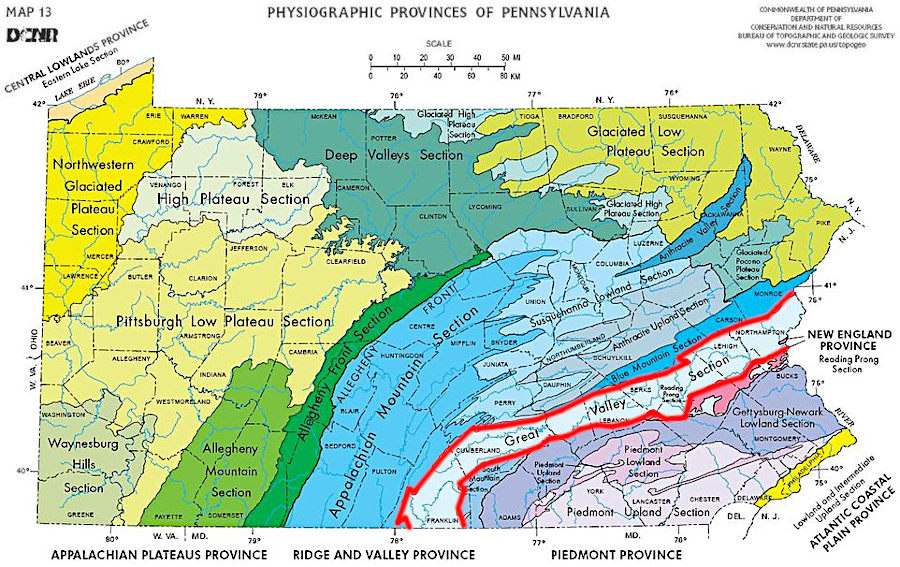

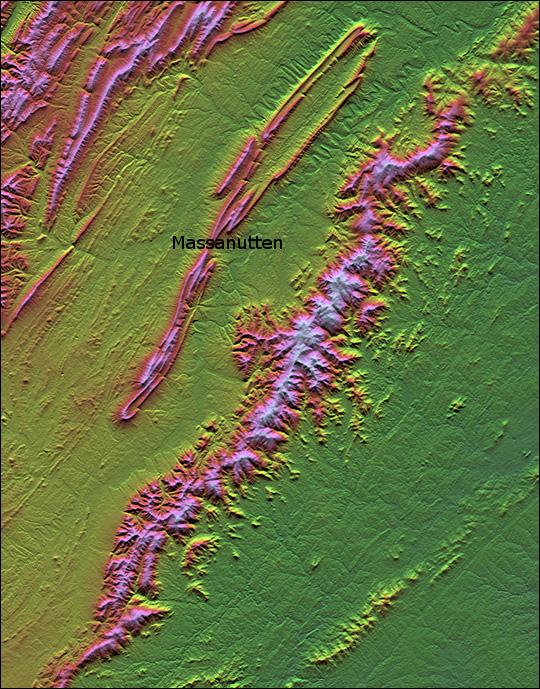

the two forks of the Shenandoah River flow north, divided by the two limbs of Massanutten Mountain (with Fort Valley between them) until the forks unite at Front Royal and the main stem joins the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Earth Observatory, The Sinuous Shenandoah

Up the Valley: In most American elementary schools, maps have been hung vertically on the classroom wall, with north at the top - and many students unconsciously assume that "north" means "up." The Shenandoah River runs north, and water flows runs downhill the whole way - even though it flows north. The mouth of the Shenandoah River is at Harpers Ferry, where the Shenandoah joins the Potomac River. Someone who floats downstream on the Shenandoah River is floating north towards the Potomac River.

If you hear a long-term resident refer to a place that is "up the valley," they mean uphill - south towards Staunton and the divide at Steele's Tavern on the Augusta/Rockbridge County border. The now-defunct Upper Valley Regional Park Authority, which used to manage Grand Caverns in Grottoes, was near Waynesboro. Compared to Luray and Front Royal and Harrisonburg, Grottoes is up the valley - not downstream near Harpers Ferry...

after Apollo 17 astronauts took the famous Blue Marble image of earth in 1972, NASA flipped the image so north would be at the top

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Agency (NASA), Celebrate Apollo: Exploring the Moon, Discovering Earth

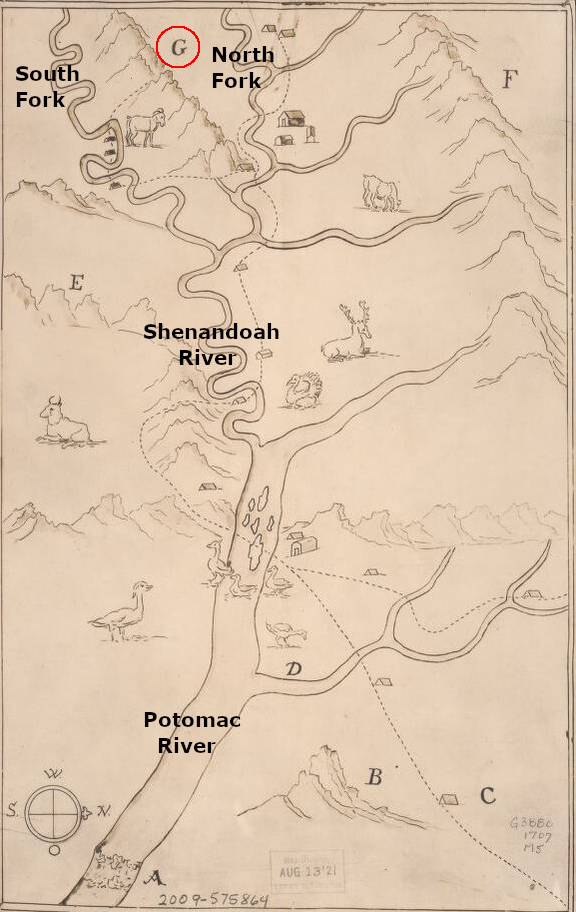

Franz Louis Michel was the first to map the Shenandoah Valley up (south) to near modern Edinburg (G=Massanutten Mountain)

Source: Library of Congress, Michel's map: 1707

the Shenandoah Valley is just one of many valleys with limestone bedrock stretching from Canada to Georgia

Source: Wikipedia, Great Appalachian Valley

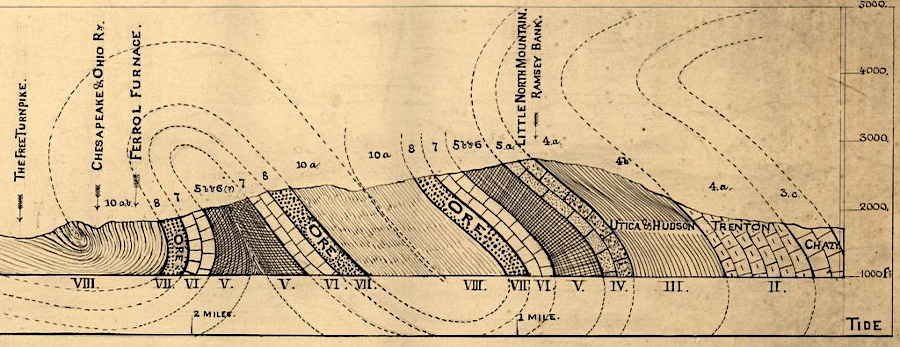

ridges west of the Blue Ridge are created by harder sandstone formations that erode slower than softer shales and sandstones

Source: Library of Congress, Section from Little North Mountain to Big North Mountain crossing S.W. of Ferrol Furnace (by John Lyle Campbell, Thomas Egleston, and Jedediah Hotchkiss, 1879?)

relief of Virginia, from Blue Ridge west through Shenandoah Valley to North Mountain (showing Massanutten Mountain in middle of the valley)

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Earth Observatory